Abstract

Benzodiazepine (BZD) use may be associated with dementia. However, differing opinions exist regarding the effect of BZDs on long-term changes in cognition. We evaluated the association between BZD use and cognitive decline in the elderly with normal cognition from the National Alzheimer’s Disease Coordinating Center’s Uniform Data Set. The study exposure, BZD use, was classified 2 ways: any use (reported BZD use at a minimum of one ADC visit) and always use (reported BZD use at all ADC visits). The reference group included participants without any declared BZD use at any ADC visit. The main outcome measures were Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) score and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score. We observed a decline in cognitive status over time in the two comparison groups. All participants who reported taking BZDs had poorer cognitive performance at all visits than nonusers. However, cognitive decline was statistically similar among all participants. We found no evidence of an association between BZD use and cognitive decline. The poor cognitive performance in BZD users may be due to prodromal symptoms caused by preclinical dementia processes.

Keywords: benzodiazepines, cognitive decline, elderly, clinical dementia rating sum of boxes, mini-mental state examination

INTRODUCTION

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are the most frequently prescribed psychotropic medication class for treating the symptoms of anxiety and sleep disorders. Typically, short and intermediate-acting BZDs are prescribed for insomnia symptoms and longer-acting BZDs treat anxiety. 1 In the United States, BZDs are the most commonly prescribed anxiolytic medications among the elderly, 2 although in other developed countries, their use is less common. 3–7

Although BZDs are approved as an effective medication regimen, some cognitive risks, including incident dementia, have been observed in conjunction with their use. 8–10 Recognized short-term effects of BZDs include impairment of new memory formation and, in some instances, complete anterograde amnesia. 11 In clinical practice, when short-term effects of BZDs on cognition are observed, lowering medication dosage has been observed as a strategy that improves the cognitive impairment. 12 The association between BZDs and long-term outcomes, however, are less clear. The majority of existing research has found a higher risk of dementia or cognitive impairment in long-term BZD users, 8–10, 13–15 though one case-control study that examined potential neuroprotective effects of BZDs reported results suggesting a potential protective effect of BZDs on cognition. 16 A meta-analysis and a literature review also have resulted in different findings on the strength of this association. 17, 18

A reverse casual link may exist between BZD use and dementia incidence and/or cognitive decline: the introduction of BZDs for treating sleep disorders or anxiety may indicate the onset of dementia-related neuropathology long before a clinical diagnosis of dementia. 12,19

In order to provide further evidence on whether exposure to BZDs is associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline, we evaluated the association of BZDs on cognitive decline in a clinic-based case series of volunteers at Alzheimer's Disease Centers, facilities across the United States that conduct a standardized evaluation of enrolled volunteers, who range from cognitively normal status to having mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders.

METHODS

Participants

Data were collected prospectively at 31 past and presently funded National Institute on Aging (NIA) ADCs between September 2005 and March 2013. 20 Study participants undergo evaluations of cognitive performance at an initial visit, and then at approximately annual follow-up visits; at each of these ADC visits, trained clinicians collect detailed information on personal characteristics, demographics, life habits, current health conditions and disease history, drug use, functional abilities, depressive symptoms and cognitive status. This information is recorded as part of the Uniform Data Set (UDS). 21 The UDS is a longitudinal, standardized data set maintained by the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC). The UDS data consists of about 725 variables obtained from annual comprehensive evaluations of 30955 research volunteers (by Dec. 2014), using up to 18 standardized forms at each visit.

Study inclusion criteria for BZD users were: (1) A minimum of one self-report of BZD use in the 2 weeks prior to an annual ADC visit. The first visit where BZD use was reported acted as study baseline for that participant; (2) a minimum of 3 years follow-up after first reported BZD use, in order to provide time to observe potential longitudinal cognitive changes; and, (3) a clinical diagnosis of normal cognition at study baseline, in order to minimize the possibility of observing an association due to reverse causation. At approximately 75–80% of ADCs, cognitive diagnosis is made after two or more clinicians discuss the patient’s clinical history and neuropsychological test performance, and reach a consensus. 22 Participants who had never reported BZD use during follow-up (no use group) served as the reference group for analysis. The reference group also was required to have a minimum of 3 years follow-up and a clinical diagnosis of normal cognition at study baseline.

Participants who were not assessed by the MMSE and CDR-SB at any of their ADC visits were excluded in our analysis.

Exposure definition and measurement

As part of the ADC evaluation, volunteers are asked to report any medications used in the two weeks prior to each annual visit. Study participants were categorized as a BZD user if they reported having taken any of the following 39 medications: alprazolam, bretazenil, bromazepam, brotizolam, chlordiazepoxide, cinolazepam, clobazam, clonazepam, clorazepate, clotiazepam, cloxazolam, delorazepam, diazepam, estazolam, etizolam, ethyl loflazepate, flunitrazepam, flurazepam, flutoprazepam, halazepam, ketazolam, loprazolam, lorazepam, lormetazepam, medazepam, midazolam, nimetazepam, nitrazepam, nordazepam, oxazepam, phenazepam, pinazepam, prazepam, premazepam, pyrazolam, quazepam, temazepam, tetrazepam and triazolam.

We defined two types of BZD exposure for analysis. The first group, any use, includes participants who reported BZD use at a minimum of one ADC visit. The second exposure group, always use, includes participants who reported BZD use at all ADC visits. We analyzed always users separately from participants with any use to evaluate possible differences in outcomes associated with consistent, long-term BZD use.

Outcome definition and measurement

We assessed cognitive change using two different outcome measures: (1) CDR-SB score; and, (2) MMSE score. The CDR-SB (Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes) evaluates cognitive and functional performance, with scores ranging from 0 to 18 (a higher score signifies more impairment).23,24 The MMSE assesses overall cognitive status, ranging from 0 to 30 points, with a lower score indicating more cognitive impairment. 25 We chose to use test scores as our outcome measures, rather than incident dementia, under the assumption that incident dementia would be difficult to observe in the relatively short follow-up time of a cohort with normal cognition at baseline.

Covariates

We adjusted for the following covariates: age (years, continuous), sex (male/female), education level (0–30 years, continuous), alcohol consumption status (yes/no), smoking status (yes/no), race (white/non-white), and presence vs. absence of self-reported history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, heart disease, stroke or transient ischemic attack, family dementia history and brain injury history at baseline.

Since depression is thought to be a potential prodromal symptom of dementia, 26 depressive symptoms were not considered as a potential confounder in our analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize baseline characteristics between the BZD any users and nonusers. We then used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to determine whether there was a difference in cognitive change over time between the BZD any use and always use groups, compared to nonusers (SPSS 19.0, IBM SPSS Inc.). Neither of the two response variables (CDR-SB, MMSE) fulfilled normality assumptions, and thus, they both were modeled as ordinal variables using logistic regression models. For our primary analysis, we implemented main effect models for BZD use and time, as well as main effect models plus an interaction between time and BZD use. For each approach, there were a total of 4 different regression models. We ran models assessing the following effects on cognitive decline: (1) BZD use (any use and always use); (2) time; (3) interaction effect between BZD use and time. As a secondary analysis, we restricted the study population to participants whose APOE e4 status was known, and ran the same models as used in the primary analysis.

In the first set of models, we evaluated the main effects of BZD use and time (years since baseline, continuous) on cognitive change over time. Because the visit intervals were approximately 1 year, time was treated as a continuous variable, coded 1–7, corresponding to visit numbers. 21 In the next set, we added an interaction term, for the interaction between time and BZD use, to the main effects model. The interaction terms allow us to test whether cognitive status in participants using BZDs declined over time more rapidly than those never using BZDs. In the third set, we focused on a subgroup of participants with APOE e4 status available. APOE e4 variant status (present/absent) was added as a covariate to the main effect models and the interaction effect models, which were implemented in the first 2 sets of analyses. In these models, we tested the association between the two exposure groups (BZD any use and always BZD use) and two outcome measures (CDR-SB, MMSE).

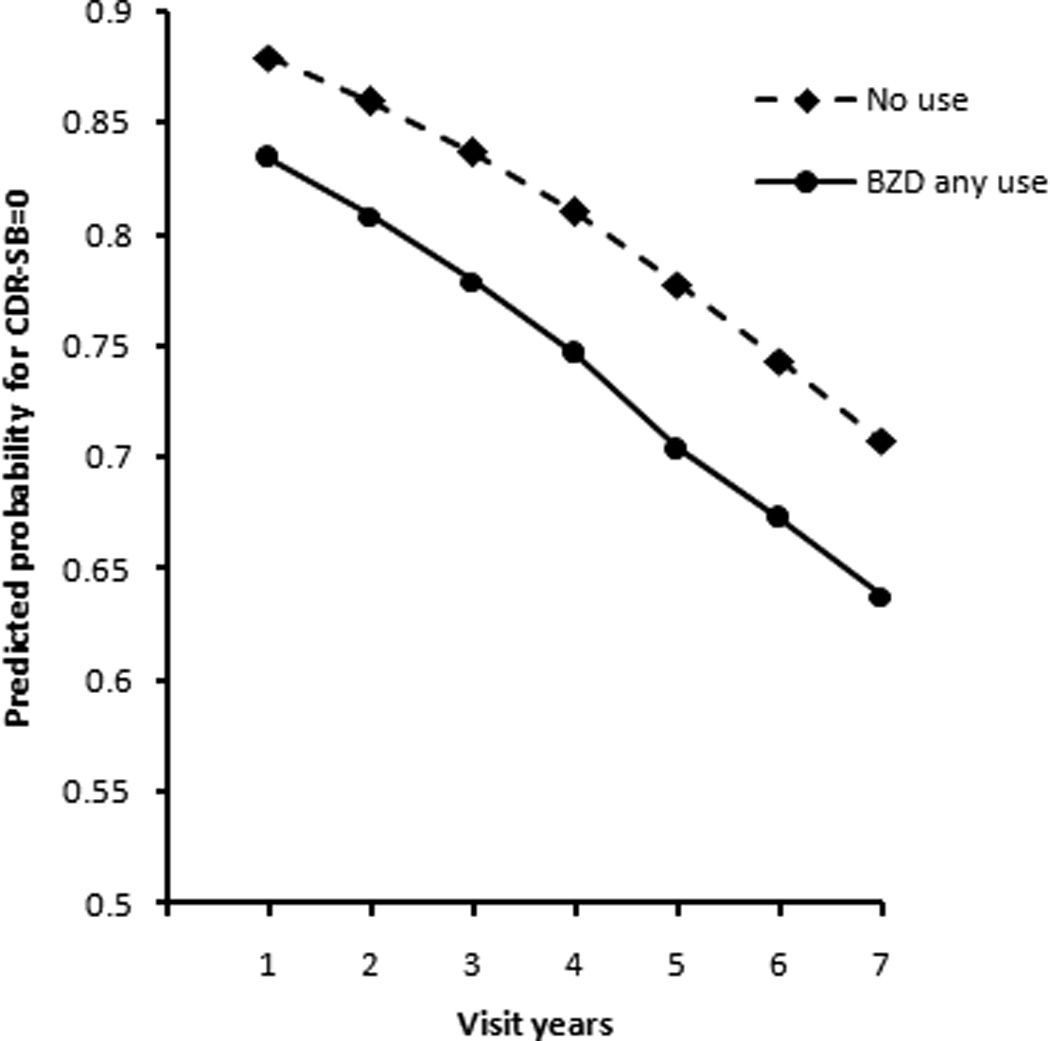

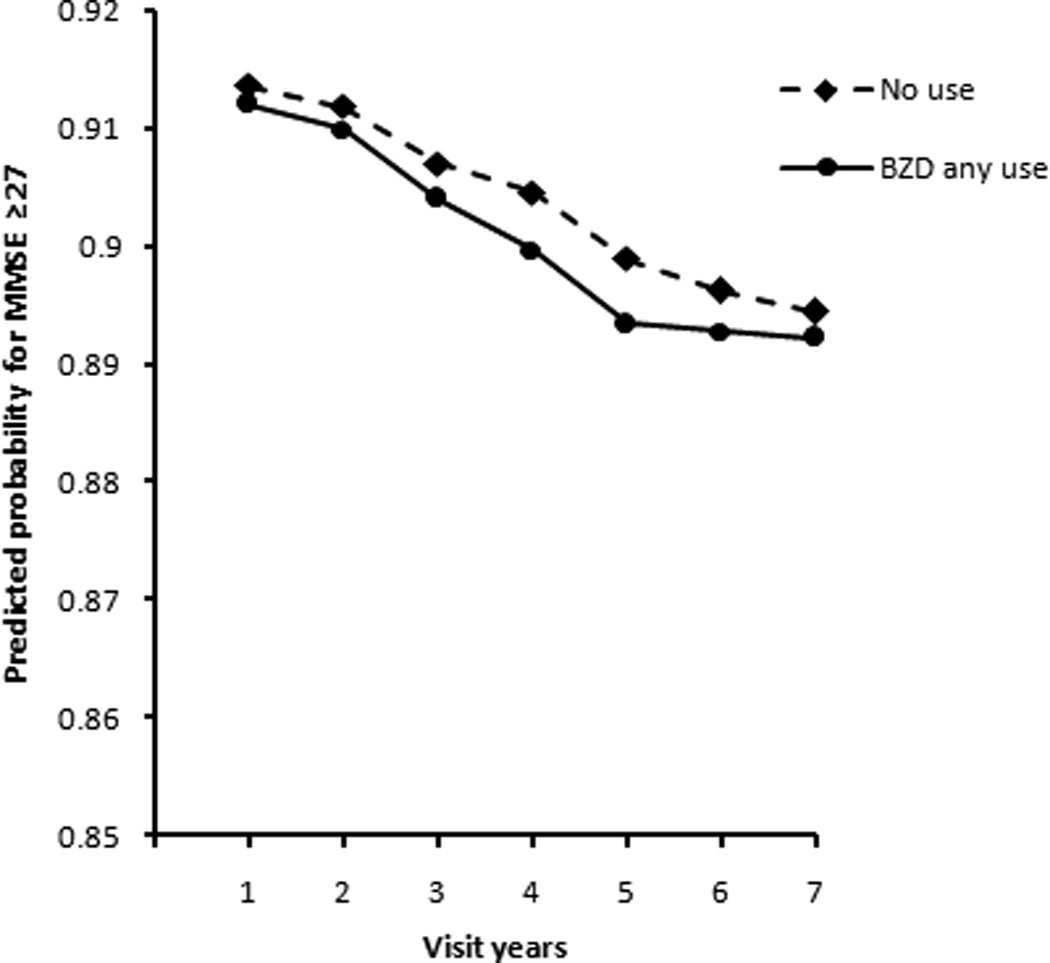

The different slopes for change over time between BZD any users and nonusers were presented graphicly based on the main effect models from the first analysis set. Because an ordinal logistic regression model was used, the predicted values were probabilities of an outcome category/range rather than a single value.

Because 16 regression models were run in total, we adjusted the threshold P-value for declaring significance in order to control Ι type error. Using the false discovery rate approximation equation α(m+1)/2m, where α is the original conventional threshold of 0.05 and m is the number of tests, the adjusted threshold P-value was 0.027. 27

RESULTS

Study participants reported having taken 11 different BZDs, which included (from highest to lowest prevalence): lorazepam, clonazepam, alprazolam, temazepam, diazepam, triazolam, oxazepam, clorazepate, chlordiazepoxide, estazolam and flurazepam.

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants included in the main analyses according to BZD exposure status at baseline. Among the 5,423 eligible participants, the mean follow-up was 4.78±1.38 years (median:5.00 years), 405 (7.5%) reported use of a BZD at least once (mean number of times reported: 3.45, SD: 1.57; the percentage of visits at which BZD use was reported was 60.7%), 177 (3.5%) reported BZD use at every ADC visit, and 5,018 (92.5%) never reported taking BZD at any visit. Mean follow-up was 5.05 (SD: 1.35) years for the any use group, 4.92 (SD: 1.38) years for the always use group, and 4.74 (SD: 1.35) years for nonusers. Although all study participants had a clinical diagnosis of normal cognition at study baseline, over 10% had CDR-SB scores > 0 and over 5% had MMSE score < 27.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between BZD any users and nonusers

| Characteristic | Nonusers (n=5018) |

Any users (n=405) |

P value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up, mean±SD (years) | 4.74±1.35 | 5.05±1.35 | <0.001 |

| Age, mean±SD (years) | 72.95±9.91 | 73.55±9.25 | 0.245 |

| Education, mean±SD (years) | 15.54±3.05 | 15.36±3.01 | 0.251 |

| Female, n(%) | 3291 (65.6) | 281 (69.4) | 0.121 |

| White, n (%) | 4110 (81.9) | 354 (87.4) | 0.005 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 129 (2.6) | 20 (4.9) | 0.005 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 2156 (43.0) | 206 (50.9) | 0.002 |

| Brain injury, n (%) | 32 (0.6) | 3 (0.7) | 0.803 |

| Depression, n (%) | 701 (14.0) | 143 (34.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2475 (49.3) | 239 (59.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 2291 (45.7) | 222 (54.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 518 (10.3) | 40 (9.9) | 0.776 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 1159 (23.1) | 125 (30.9) | <0.001 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack, n (%) | 291 (5.8) | 45 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| APOE e4 variant, n (%)b | 1163 (28.5) | 90 (28.0) | 0.821 |

| Subjects with CDR-SB score >0, n (%)c | 593 (11.8) | 63 (15.6) | 0.026 |

| Subjects with MMSE score <27, n (%)d | 313 (6.6) | 23 (5.8) | 0.562 |

p-value of t test for follow-up years, age and education years and of chi-square test for others.

Based on the participants with APOE e4 data (322 BZD any users vs 4,075 nonusers)

CDR-SB data were missing for some participants (276 missing in BZD any users and 9 missing in nonusers) at baseline.

MMSE data were missing for some participants (243 missing in BZD any users and 9 missing in nonusers) at baseline.

Many statistically significant differences existed between BZD any users and nonusers at baseline. Compared with nonusers, BZD any users were more likely to report alcohol and tobacco use, to be white, and to have a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms. Also, BZD any users were more likely to report a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, heart disease and stroke or transient ischemic attack. Baseline MMSE score was not statistically significant different between BZD any users and nonusers, but baseline CDR-SB score was higher for BZD any users than nonusers.

Main effects models for time estimated that cognition declined significantly over time, as measured by both the MMSE and CDR-SB (Table 2). The main effects for BZD use were inconsistent on MMSE score and CDR-SB score. No significant association between BZD use and MMSE was observed. However, compared to no BZD use, the associations between BZD use and CDR-SB was observed to be significant. The results were consistent in despite of two comparisons (any use vs. no use, always use vs. no use).

Table 2.

Longitudinal regression analyses using Generalized Estimating Equations of cognitive tests regressed on time and benzodiazepine (BZD) use

| Regression Coefficient (P value) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure group | Diagnostic Test | BZD use | Time | Interaction term (BZD*time) |

|

| Any use vs. no use | CDR-SB | 0.326 (0.001) | 0.187 (<0.001) | −0.011 (0.842) | |

| MMSE | −0.142 (0.085) | −0.064 (<0.001) | 0.089 (0.766) | ||

| CDR-SB* | 0.029 (0.006) | 0.194 (<0.001) | 0.027 (0.595) | ||

| MMSE* | −0.032 (0.774) | −0.040 (0.005) | 0.016 (0.927) | ||

| Always use vs. no use | CDR-SB | 0.352 (0.009) | 0.184 (<0.001) | 0.002 (0.972) | |

| MMSE | −0.022 (0.837) | −0.063 (<0.001) | −0.066 (0.228) | ||

| CDR-SB* | 0.264 (0.083) | 0.190 (<0.001) | 0.024 (0.688) | ||

| MMSE* | 0.065 (0.996) | −0.039 (0.005) | −0.027 (0.674) | ||

All models were adjusted for age (continuous, years), sex, race (white/non-white), education (continuous, years), family history (first-degree relative with dementia), and history of heart disease, stroke or transient ischemic attack, diabetes mellitus, brain injury, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and tobacco and alcohol use at baseline.

Supplemental analysis for subjects with APOE e4 data. APOE e4 variant status (present/absent) was added to the models as a covariate.

In all interaction effect models, the interaction term was not significant, indicating no difference in cognitive changes over time between any users/always users and nonusers. In other words, although the cognition of both any users/always users and nonusers significantly declined over time, the cognition of any users/always users did not decline faster than nonusers over time.

APOE e4 status was available for 4,398 (81.1%) participants. Only one finding changed in our supplemental analyses. After adjusting for APOE e4 variant status in a main effects model, the effect of always use on CDR-SB was not significant (P=0.083).

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the trend of cognitive decline in our study cohort. Figure 1 shows the slopes for CDR-SB change over time between BZD any use group and no use group based on a main effect model. The vertical axis is the predicted probability for CDR-SB score to be 0 (tend to normal cognition). A larger probability indicates that the CDR-SB score of participants was more likely to be 0. The results showed that the probability of normal cognition, measured by the CDR-SB, for both the BZD any use group and the no use group declined over time; however, the slopes for change were not different, indicating no interaction effect between any BZD use and time.

Figure 1.

Change in predicted probability for CDR-SB to be 0 over annual visits for participants with normal cognition at baseline, BZD any use group vs. no use group, based on main effect model.

Figure 2.

Change in predicted probability for MMSE≥27 over annual visits for participants with normal cognition at baseline for BZD any use group and no use group, based on main effect model.

Figure 2 shows the slopes for MMSE score change over time between the BZD any use group and no the use group based on the main effect model. The vertical axis represents the predicted probability of an MMSE score greater than or equal to 27, where a larger probability indicates that participants' MMSE scores were more likely to be in the normal cognition range. Although the probability for both the BZD any use group and the no use group declined over annual ADC visits, the decline was slight (the probability decreased from 0.91 to 0.89) and did not differ statistically between these groups.

DISCUSSION

We did not observe an association between BZDs and cognitive decline. Additionally, we did not detect a faster decline in cognitive status among participants reporting BZD use, compared to participants not reporting BZD use.

Our findings were consistent with three previous case-control studies that reported no significant association between BZD use and cognitive function impairment. 28–31 Among the existing studies, a variety of different tools were used to measure cognitive status, and most studies had a sample size smaller than ours, which may explain some of the differences in findings. In one prospective study, using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ), BZD dose and duration of use were associated with poorer memory. 3 More recent cohort studies also have reported that long-term BZD use leads to long-term memory impairment, specifically in women. 13

Insomnia, depression and anxiety are often prodromal symptoms of cognitive decline, all of for which BZDs are commonly prescribed. 8 A major challenge of observational studies is collecting data over a long enough time period to minimize the possibility of reverse causation. In our study, although all participants were cognitively normal at baseline, a small but significant difference in cognitive status, as measured by the CDR-SB, persisted between BZD any users and nonusers. We chose CDR-SB and MMSE as study outcomes in hope that they would be more sensitive to cognitive change over time, and were more appropriate endpoints than an incident dementia diagnosis for our study population, due to the relatively short follow-up time.

This study had several strengths. First, data were collected using standardized cognitive testing at each ADC visit and, subsequently, the cognitive status of participants was diagnosed by clinicians, ensuring the reliability of measure data. Secondly, APOE e4 variant is a well known risk factor for both dementia and cognitive decline. Although unavailable for all study participants, we were able to adjust our primary analysis models for APOE e4 allele status, information unavailable in most previous studies. 3, 8–10, 13–15, 31 An additional strength of our study was its longitudinal nature, allowing us to use measurements from multiple, consecutive ADC visits to assess cognitive change, rather than compare only baseline and endpoint data.

Our study also had some limitations. We had relatively small sample sizes of BZD any users and always users, thereby limiting the power for analyses. Secondly, the study was based on a short follow-up period relative to potential effects of BZDs, which limited our ability to assess the delayed effects of BZD exposure. More specifically, if exposure to BZDs leads to delayed adverse outcomes, past the time window captured in our cohort, we would be unable to detect such changes. Several studies that found adverse cognitive outcomes associated with BZD use have more than 5 years of follow-up after initiation of BZD treatment.8–10,15 Lastly, information was unavailable regarding specific details of BZD medication history. Thus, we had no information regarding the precise duration of BZD use for participants, nor did we have information on medication dosage, both of which could influence our findings if a dose-response relationship exists or if duration of exposure is associated with cognitive decline. Moreover, subjects were just asked for medication use only in the 2 weeks prior to an annual ADC visit, thus, if BZD was taken in the following weeks by these participants, they would have been misclassified as non-users, underestimating the level of exposure in our study.

In conclusion, we did not find evidence that BZD use was associated with cognitive decline in our cohort. The poorer cognitive performance observed in BZD users may be due to the prescription of BZD to treat prodromal symptoms of dementia before the condition is clinically diagnosed. Even if confounding by indication had created a bias in which BZD users would represent participants with more advanced underlying neuropathology, we did not find a difference in slopes of cognitive decline.

Benzodiazepines remain useful for the treatment of anxiety and insomnia. Further research should explore whether there is an association between dosage or cumulative length of exposure to BZDs and cognitive decline in larger cohorts with longer follow-up time. Additionally, researchers may consider whether changes in BZD regimens will influence cognitive functioning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the ADC participants for their willingness to devote their time to research and the ADC staff members for their work.

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI David Teplow, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), and P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD).

This study was supported by the State Scholarship Fund of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30901241).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashton H. Guidelines for the rational use of benzodiazepines. Drugs. 1994;48:25–40. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulose-Ram R, Safran MA, Jonas BS, et al. Trends in psychotropic medication use among US adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:560–570. doi: 10.1002/pds.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanlon JT, Horner RD, Schmader KE, et al. Benzodiazepine use and cognitive function among community-dwelling elderly. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:684–692. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fourrier A, Letenneur L, Dartigues J, et al. Benzodiazepine use in an elderly community-dwelling population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:419–425. doi: 10.1007/s002280100326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magrini N, Vaccheri A, Parma E, et al. Use of benzodiazepines in the Italian general population: prevalence, pattern of use and risk factors for use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s002280050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tu K, Mamdani MM, Hux JE, et al. Progressive trends in the prevalence of benzodiazepine prescribing in older people in Ontario, Canada. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1341–1345. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Windle A, Elliot E, Duszynski K, et al. Benzodiazepine prescribing in elderly Australian general practice patients. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31:379–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billioti de Gage S, Begaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. Br Med J. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallacher J, Elwood P, Pickering J, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: evidence from the Caerphilly Prospective Study (CaPS) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:869–873. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagnaoui R, Bégaud B, Moore N, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: A nested case–control study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:314–318. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campagne DM. Fact: antidepressants and anxiolytics are not safe during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;135:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bocti C, Roy-Desruisseaux J, Roberge P. Research paper most likely shows that benzodiazepines are used to treat early symptoms of dementia. Br Med J. 2012;345:e7986. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boeuf-Cazou O, Bongue B, Ansiau D, et al. Impact of long-term benzodiazepine use on cognitive functioning in young adults: the VISAT cohort. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:1045–1052. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1047-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu C-S, Wang S-C, Chang I, et al. The association between dementia and long-term use of benzodiazepine in the elderly: nested case–control study using claims data. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:614–620. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181a65210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu C-S, Ting T-T, Wang S-C, et al. Effect of benzodiazepine discontinuation on dementia risk. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:151–159. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181e049ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fastbom J, Forsell Y, Winblad B. Benzodiazepines may have protective effects against Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1998;12:14–17. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M, et al. Cognitive effects of long-term benzodiazepine use. CNS drugs. 2004;18:37–48. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verdoux H, Lagnaoui R, Begaud B. Is benzodiazepine use a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia? A literature review of epidemiological studies. Psychol Med. 2005;35:307–315. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyle-Gilchrist IT, Peck LF, Rowe JB. Research paper does not show causal link between benzodiazepine use and diagnosis of dementia. Br Med J. 2012;345:e7984. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steenland K, Zhao L, Goldstein FC, et al. Statins and cognitive decline in older adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1449–1455. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bristow KE, Besser LM, Monsell SE, Brenowitz W, Hawes SE, Kukull WA. Consensus diagnosis and predictors of diagnostic accuracy in the National Alzheimer's Disease Centers. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:321. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tractenberg RE, Weiner MF, Cummings JL, et al. Independence of changes in behavior from cognition and function in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease: a factor analytic approach. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17:51–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li G, Wang LY, Shofer JB, et al. Temporal relationship between depression and dementia: findings from a large community-based 15-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:970–977. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B (Stat Method) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puustinen J, Nurminen J, Kukola M, et al. Associations between Use of Benzodiazepines or Related Drugs and Health, Physical Abilities and Cognitive Function. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:1045–1059. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724120-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dealberto MJ, Mcavay GJ, Seeman T, et al. Psychotropic drug use and cognitive decline among older men and women. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allard J, Artero S, Ritchie K. Consumption of psychotropic medication in the elderly: a re-evaluation of its effect on cognitive performance. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:874–878. doi: 10.1002/gps.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38:226–228. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]