1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain is a priority health issue [5], which currently is the topic of the 2014–2015 Global Year Against Neuropathic Pain campaign of the International Association for the Study of Pain (http://www.iasp-pain.org/GlobalYear/NeuropathicPain). Between 6% and 10% of adults are affected by chronic pain with neuropathic features [6,14,25], and this prevalence is significantly greater among individuals with specific conditions. For example, neuropathic pain is a common comorbidity in infectious diseases such as HIV, leprosy, and herpes zoster, and in non-infectious conditions such as diabetes mellitus, stroke, multiple sclerosis, and traumatic limb and spinal cord injury [7,13,16,19,21]. The pain is associated with significant decreases in quality of life and socioeconomic well-being, even more so than non-neuropathic chronic pain [9,20,22]. Developing and emerging countries share the greatest burden of conditions that predispose to development of neuropathic pain [5,10], and can ill afford the negative consequences of this pain.

There are medicines with proven efficacy in the treatment of neuropathic pain [11,12]. Nevertheless, the pain can be difficult to treat, with significant inter-individual variation in efficacy within and between drug classes, independent of the presumed aetiology of the neuropathy [2,4]. Effective management of neuropathic pain within a population therefore requires access to a small, but crucial group of drug classes with proven efficacy.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) model list of essential medicines (http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/list/en/) presents those medicines deemed necessary to meet priority health needs, and local implementation of essential medicines policies is associated with improved quality use of medicines [15,18]. But, none of the analgesic medicines included in the WHO model list are recommended as first-line treatments for neuropathic pain [11]. Thus the WHO model list is not a good framework from which national policies on managing neuropathic pain can be structured and countries routinely adapt the model list according to local needs and resources [18]. To estimate the nominal availability of medicines recommended for the treatment of neuropathic pain in developing and emerging countries, we assessed national essential medicines lists (NEMLs) for the inclusion of recommended treatments. We also assessed whether the coverage of recommended drugs classes on these NEMLs was dependent on countries’ economic status.

2. Methods

2.1.National Essential Medicines List(NEML) selection

We confined our analysis to the 117NEMLs accessible through the WHO website (http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/country_lists/en/).Updated editions of the 117 NEMLs were sought on public crawler-based search engines using country names, and titles of the downloaded documents as search terms; 14 newer editions were identified.

2.2. Data extraction

Each NEML was independently reviewed by two authors. NEMLs were assessed for drugs recently recommended as first or second-line treatments for neuropathic pain after a meta-analysis and grading of the evidence [11]. Drug classes and drugs assessed included: i) tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) - amitriptyline, nortriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, and imipramine; ii) serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) - duloxetine and venlafaxine; iii) anticonvulsants - gabapentin and pregabalin; iv) opioids - tramadol; and v) topical agents - capsaicin and lidocaine. Drugs were recorded as being listed if they appeared anywhere on an NEML, irrespective of therapeutic class classification or treatment indications. Lidocaine was only recorded as being listed if it was specified as a topical formulation and at a concentration of at least 5%, or was a eutectic mix of 2.5% lidocaine:2.5% prilocaine. Capsaicin was only recorded as being listed if the concentration was specified to beat least 8%. Information was also extracted on the strong opioids morphine, methadone, and oxycodone, which are listed in the WHO model list and are recommended as second or third-line therapy for neuropathic pain [3,11]. Anticonvulsants that are listed on the WHO model list, but for which the data on their efficacy in treating neuropathic pain are inconclusive (carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine) or against their use (sodium valproate), were also assessed [11].

2.3. Data analysis

Only countries and territories classified as developing or emerging by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were included in the analysis, which resulted in the exclusion of NEMLs from Sweden, Malta, Slovenia, and Slovakia [17]. The NEML of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea also was excluded because the list was generated by the WHO, and not by the country itself. The NEMLs of the remaining 112 countries were then categorised according to the World Bank system of low, lower-middle, higher-middle and high income [23]. Data from 8 countries (Bahrain, Barbados, Chile, Croatia, Oman, Poland, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay), which are classified as developing or emerging by the IMF, but as high income by the World Bank, were included in the analyses. Basic descriptive statistics were generated on whether the selected drugs were listed, and the number of recommended first-line drug classes included on each NEML. Chi-square test for trend was used to assess whether country income category predicted which of the drugs assessed were listed, and the number of first and second-line drug classes listed. The Holm method was used to correct p-values for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Coverage of developing and emerging countries

The 112 documents analysed covered 24/34 (71%) developing or emerging countries and territories classified as low income by The World Bank, 40/50 (80%) countries classified as lower-middle income, 37/55 (67%) countries classified as higher-middle income, and 8/38 (21%) developing or emerging countries and territories classified as high income [23]. Thirty-nine (39) countries were in Africa, 23 in the Americas, 30 in Asia (including the Middle East), 8 in Europe, and 12 in Oceania. The median NEML publication date was 2009 [range: 2002 to 2014]. Additional information on the 112 NEMLs is provided in Supplementary File 1.

3.2. Listing of individual drugs

Table 1 summarizes the listing of individual drugs. Tricyclic antidepressants were almost universally listed, with amitriptyline being the most commonly listed agent. Only the NEMLs of Angola, Bulgaria, and Cambodia did not list any of the assessed TCAs. There was a positive association between country income and listing of imipramine (corrected p-value = 0.037), but not of the other TCAs. Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and venlafaxine were infrequently listed, and no association was detected between drug listing and country income. The majority of NEMLs did not include an α2δ calcium channel antagonist, but when they did, it was more likely to be gabapentin than pregabalin, and the NEML was more likely to be from an upper-middle income or high income country than a country from a lower income category (corrected p-value = 0.005).

Table 1.

Drug listings on the national essesntial medicines lists of 112 developing countries

| Overall listing n (%) |

Listing by World Bank income category [n (% countries within a category)] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 24) |

Lower middle (n = 40) |

Upper middle (n = 37) |

High (n = 8) |

Other1 (n = 3) |

||

| FIRST-LINE MEDICATIONS | ||||||

| TCA | ||||||

| Amitriptyline | 105 (94) | 23 (96) | 38 (95) | 33 (89) | 8 (100) | 3 (100) |

| Clomipramine | 53 (47) | 11 (46) | 21 (52) | 16 (43) | 5 (62) | 0 (0) |

| Desipramine | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Imipramine2 | 46 (41) | 3 (12) | 17 (42) | 20 (54) | 6 (75) | 0 (0) |

| Nortriptyline | 10 (9) | 1 (4) | 2 (5) | 6 (16) | 1 (12) | 0 (0) |

| SNRI | ||||||

| Duloxetine | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 1 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Venlafaxine | 19 (17) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 8 (22) | 4 (50) | 0 (0) |

| α2δ antagonist | ||||||

| Gabapentin2 | 33 (30) | 1 (4) | 10 (25) | 16 (43) | 6 (75) | 0 (0) |

| Pregabalin | 11 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 6 (16) | 1 (12) | 1 (33) |

| SECOND-LINE MEDICATIONS | ||||||

| Opioid | ||||||

| Tramadol | 61 (55) | 8 (33) | 19 (48) | 26 (70) | 7 (88) | 1 (33) |

| Topical | ||||||

| 8% capsaicin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 5% lidocaine | 22 (20) | 3 (12) | 6 (15) | 9 (24) | 3 (38) | 1 (33) |

| STRONG OPIOID MEDICATIONS | ||||||

| Methadone2 | 34 (30) | 4 (17) | 8 (20) | 16 (43) | 6 (75) | 0 (0) |

| Morphine | 106 (95) | 22 (92) | 40 (100) | 33 (89) | 8 (100) | 3 (100) |

| Oxycodone | 15 (13) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | 9 (24) | 2 (25) | 0 (0) |

| OTHER ANTICONVULSANT MEDICATIONS | ||||||

| Carbamazepine | 109 (97) | 22 (92) | 40 (100) | 36 (97) | 8 (100) | 3 (100) |

| Oxcarbazepine2 | 15 (13) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 8 (22) | 4 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Sodium valproate | 107 (95) | 22 (92) | 40 (100) | 35 (95) | 7 (88) | 3 (100) |

Countries not included on the World Bank income list: Cook Islands, Nauru, Niue;

p<0.05 for chi-square test for trend (listing vs income category); TCA: Tricyclic antidepressants; SNRI: Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors; α2δ antagonist: α2δ calcium channel antagonists

Roughly half the NEMLs listed tramadol, and no association was detected between income category and drug listing. Only one-fifth of countries’ lists included topical lidocaine (no association between income and drug listing was detected), and none of the NEMLs included high-dose capsaicin.

Morphine, and the anticonvulsants carbamazepine and sodium valproate, were almost universally listed (see Supplementary File 2 for countries that did not list morphine), and no associations between income and drug listings were detected. There were low rates of inclusion for other strong opioids, oxycodone and methadone, and the anticonvulsant oxcarbazepine. Inclusion of methadone and oxcarbazepine was positively associated with country income status (corrected p-value < 0.05 for both drugs).

Very few NEMLs indicated that the assessed drugs were for the treatment of neuropathic pain, with amitriptyline (9% NEMLs) and carbamazepine (14% of NEMLs) receiving the most indications for treating neuropathic pain (Supplementary File 3).

3.3. Listing of drug classes

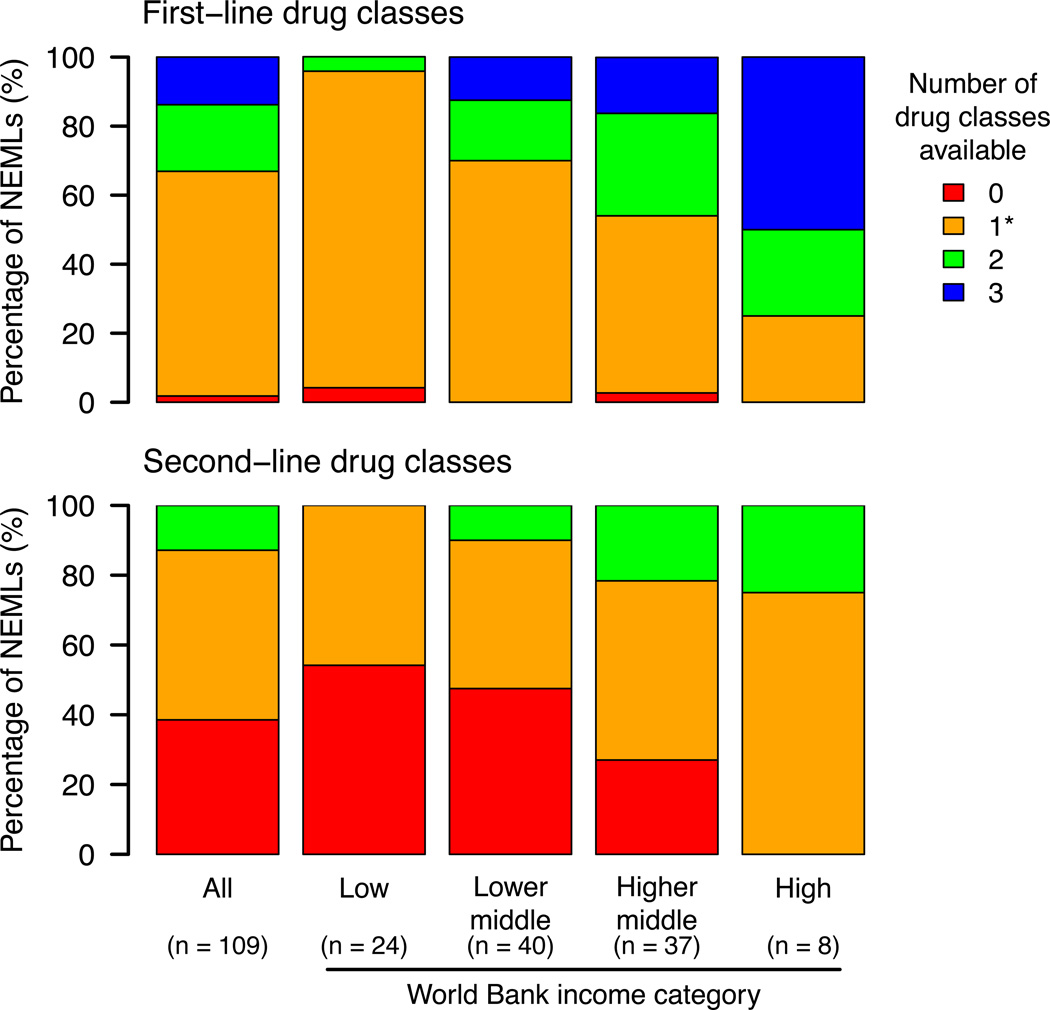

Figure 1 shows the number of recommended first-line and second-line drug classes listed. Approximately two-thirds of countries had only one class of first-line agent (typically TCAs), and approximately half had only one second-line agent (typically tramadol), included on their NEMLs. Two countries (Angola and Cambodia) had no first-line treatment classes listed, and almost 40% of countries had no second-line therapies listed. There was an association between income category and number of drug classes listed for first (corrected p-value < 0.001) and second-line (corrected p-value < 0.001) therapies. No low-income countries had all three first-line drug classes listed, compared to half of all high income countries. Only one low-income country (Tanzania) had two first-line classes listed (TCA and α2δ calcium channel antagonists), compared to one-quarter of high income countries.

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

Our analysis of 112 NEMLs from developing and emerging countries or territories shows gross deficiencies in the scope of drugs included on these lists that are recommended for the treatment of neuropathic pain. The poor selection of recommended treatments means that should a patient fail to respond to initial therapy (number needed to treat for 50% pain relief is typically ≥4 for neuropathic pain [11]), have significant side effects, or have contraindications to a drug’s use, there are no or limited alternative therapies available. Further, even when recommended drugs are listed, the drugs generally are not indicated, or are inappropriately indicated, for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

The management of pain is a priority issue that has been codified in the WHO model list since 1977 [27,29]. Indeed, the WHO [28] recently urged member states to ensure, “the availability of essential medicines for the management of symptoms, including pain”, and “ [the] education and training of healthcare professionals, in order to ensure adequate responses to palliative care needs”. Yet for neuropathic pain the WHO model list fails on both accounts, being deficient in drugs with proven efficacy in treating neuropathic pain, and it provides no guidance on appropriate medications to use for treating neuropathic pain. These deficiencies are echoed in the NEMLs of developing and emerging countries. However, while the WHO model list informs the development of NEMLs, countries tailor their lists according to local needs. For example, tramadol was included on about half the NEMLs we assessed, but it is not on the WHO model list. Thus, the dearth of recommended medications for treating neuropathic pain reflects deficiencies at the international and national level.

4.1 Limitations

Our assessment was limited to 112 developing or emerging countries, and the median publication date of the NEML assessed was 2009. Nevertheless we believe that our assessment provides an accurate appraisal of the current situation. First, our sample included the majority of countries classified as low, lower-middle, and higher-middle income. Secondly, no medications relevant to the treatment of neuropathic pain have been added to the WHO model list in over a decade [30,31]. And finally, since 2009, only about 5% of countries have transitioned to a higher World Bank income category.

Indeed, NEMLs only indicate nominal drug availability, and despite widespread adoption of the essential medicine concept, actual drug availability tends to be low in developing countries because of factors such as policy implementation, infrastructure and appropriate logistical support, drug cost, availability of reimbursement, and knowledge of healthcare professionals [24,26,32]. Furthermore, most of the medications to treat neuropathic pain are included on NEMLs as treatments for depression or epilepsy. Stigma toward these conditions by communities and healthcare providers may be an important barrier to inclusion on NEMLs and their use by healthcare providers and patients [1,8]. Thus, our analysis probably overestimates the actual availability of neuropathic pain medications in these countries.

4.2 Recommendations

As a first step to improving the management of neuropathic pain, we believe that there is a strong enough therapeutic need and a sufficient evidence base to warrant applying for inclusion of additional recommended treatments for neuropathic pain in the 19th edition of the WHO model NEML. Indeed, the need to expand the scope of essential medicines lists is one of the subjects of a commission on essential medicine policies recently established by The Lancet (http://www.bu.edu/lancet-commission-essential-medicines-policies/). To facilitate the appropriate use of these medications, they should be listed under a neuropathic pain subsection of the “pain and palliative care” section of the WHO model list. In addition, we also motivate for research into the actual cost and availability of these medications in rural and urban settings, and to identify the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and training needs of prescribers that are required to improve access to care for neuropathic pain treatments worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Adelade Masemola, Arista Botha, and ZiphoZwane for assisting with data extraction.

AH received honoraria or consultancy fees from AbbVie, Glaxo Smith Kline, Lilly, Mundipharma, Pfizer and Sanofi in the past 36 months. PRK declared consultancy fees from Reckitt Benckiser, lecture fees from Pfizer and Novartis, and travel support from Janssen. ACM declared receiving research support from the US National Institutes of Health, World Federation of Neurology, a drug donation from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, and travel support from Abbott Pharmaceuticals. ASCR undertakes consulting for Imperial College Consultants, and in the past 36 months received fees from Spinifex Pharmaceuticals, As tell as, Servier, Abide, Relmada, Allergan, AsahiKasei, and Medivir. ASCR’s laboratory received research funding from Pfizer and Astellas. SNR received research funding from Medtronic, and was a member of an advisory board for Mistsibushi Tanabe and QRxPharma. BHS declared receiving occasional lecture and consultancy fees in the past 36 months, on behalf of his institution, from Pfizer, Napp and Grunenthal. RDT received research support or honoraria from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, AWD, Bauerfeind, BoehringerIngelheim, BundesministeriumfürBildung und Forschung, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, European Union, Glaxo Smith Kline, Grünenthal, Kade, Lily, Merz, Mundipharma, Nycomed, Pfizer, Sanofi, StarMedTec, Schwarz, US National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

ALW, KD, PJ, AK, and PJW declared no conflicts on interest.

References

- 1.Almanzar S, Shah N, Vithalani S, Shah S, Squires J, Appasani R, Katz CL. Knowledge of and attitudes toward clinical depression among health providers in Gujarat, India. Ann. Glob. Heal. 2014;80:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attal N, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dostrovsky J, Dworkin RH, Finnerup N, Gourlay G, Haanpaa M, Raja S, Rice ASC, Simpson D, Treede R-D. Assessing symptom profiles in neuropathic pain clinical trials: can it improve outcome? Eur. J. Pain. 2011;15:441–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Nurmikko T. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010;17:1113–e1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron R, Förster M, Binder A. Subgrouping of patients with neuropathic pain according to pain-related sensory abnormalities: a first step to a stratified treatment approach. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond M, Breivik H, Jensen TS, Scholten W, Soyannwo O, Treede R-D. Neurological disorders: public health challenges. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. Pain associated with neurological disorders; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherry CL, Wadley AL, Kamerman PR. Painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Pain Manag. 2012;2:543–552. doi: 10.2217/pmt.12.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chomba EN, Haworth A, Atadzhanov M, Mbewe E, Birbeck GL. Zambian health care workers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doth AH, Hansson PT, Jensen MP, Taylor RS. The burden of neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of health utilities. Pain. 2010;149:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dua T, Garrido Cumbrera M, Mathers C, Saxena S. Neurological disorders: public health challenges. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. Global burden of neurological disorders: estimates and projections; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpaa M, Jensen TS, Kamerman PR, Lund K, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice AS, Sena E, Smith BH. Pharmacotherapy of neuropathic pain: systematic review, meta-analysis and NeuPSIG recommendations. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. [Under review: Lancet Neuol]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haroun OMO, Hietaharju A, Bizuneh E, Tesfaye F, Brandsma JW, Haanpää M, Rice ASC, Lockwood DNJ. Investigation of neuropathic pain in treated leprosy patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Pain. 2012;153:1620–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan Ra, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. 2014;155:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloway KA, Henry D. WHO essential medicines policies and use in developing and transitional countries: an analysis of reported policy implementation and medicines use surveys. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu E, Cohen SP. Postamputation pain: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. J. Pain Res. 2013;6:121–136. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S32299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook - recovery strengthens, remains uneven. [Accessed 18 Aug 2014];2014 Available: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2014/01/pdf/text.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laing R, Waning B, Gray A, Ford N, ’t Hoen E. 25 years of the WHO essential medicines lists: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2003;361:1723–1729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasry-Levy E, Hietaharju A, Pai V, Ganapati R, Rice ASC, Haanpää M, Lockwood DNJ. Neuropathic pain and psychological morbidity in patients with treated leprosy: a cross-sectional prevalence study in Mumbai. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5:e981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poliakov I, Toth C. The impact of pain in patients with polyneuropathy. Eur. J. Pain. 2011;15:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadosky A, McDermott AM, Brandenburg NA, Strauss M. A review of the epidemiology of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, post herpetic neuralgia, and less commonly studied neuropathic pain conditions. Pain Pract. 2008;8:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2007.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith BH, Torrance N. Epidemiology of neuropathic pain and its impact on quality of life. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The World Bank. Countries and economies: income levels. [Accessed 18 Aug 2014];2014 Available: http://data.worldbank.org/country. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson S, Ogbe E. Helpdesk Report: availability of essential medicines. Human Development Resource Centre. 2012;24 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torrance N, Smith BH, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. J. Pain. 2006;7:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.UN Millennium Project. Prescription for healthy development: increasing access to medicines. London: Earthscan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization (WHO) Essential medicines in palliative care. [Accessed 20 Oct 2014];2013 Available: http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/19/applications/PalliativeCare_8_A_R.pdf.

- 28.World Health Organization (WHO) Resolution EB134.R7: Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment within the continuum of care. [Accessed 4 Sep 2014];2014 Available: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_31-en.pdf.

- 29.World Health Organization (WHO) The selection of essential drugs. [Accessed 22 Oct 2014];1977 Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/41272/1/WHO_TRS_615.pdf.

- 30.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO model list of essential medicines - 18th edition. [Accessed 5 Feb 2013];2013 2013 Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/18th_EML_Final_web_8Jul13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO model list of medicines - 12th edition. [Accessed 3 Nov 2014];2002 Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/a76618.pdf?ua=1.

- 32.World Health Organsization (WHO) WHO medicines strategy: countries at the core (2004–2007) [Accessed 12 Nov 2014];2004 Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s5416e/s5416e.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.