Summary

Background

There is increasing evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted adversely on the provision of essential health services globally. The Southeast Asia region (SEAR) has experienced extremely high rates of COVID-19 infection, with potential adverse impacts on provision of reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health (RMNCH) services.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review of quantitative evidence to characterise the impact of COVID-19 on the provision of essential RMNCH services across the SEAR. Studies published between December 2019 and May 2022 were included in the study. The quality of studies was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist.

Findings

We reviewed 1924 studies and analysed data from 20 peer-reviewed studies and three reports documenting quantitative pre-post estimates of RMNCH service disruption because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eleven studies were of low methodological quality, in addition to seven and five studies of moderate and high methodological qualities respectively. Six countries in the region were represented in the included studies: India (11 studies), Bangladesh (4), Nepal (3), Sri Lanka (1), Bhutan (1) and Myanmar (1). These countries demonstrated a wide reduction in antenatal care services (−1.6% to −69.6%), facility-based deliveries (−2.3% to −52.4%), child immunisation provision (−13.5% to −87.7%), emergency obstetric care (+4.0% to −76.6%), and family planning services (−4.2% to −100%).

Interpretation

There have been large COVID-19 pandemic related disruptions for a wide range of RMNCH essential health service indicators in several SEAR countries. Notably, we found a higher level of service disruption than the WHO PULSE survey estimates. If left unaddressed, such disruptions may set back hard-fought gains in RMNCH outcomes across the region. The absence of studies in five SEAR countries is a priority evidence gap that needs addressing to better inform policies for service protection.

Funding

WHO Sri Lanka Country Office.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Maternal health, Antenatal care, Reproductive health, Neonatal health, Child health, Southeast Asia region

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

It has been well-documented that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on the provision of essential health services, and that this is especially so in countries where health systems were already under-resourced and overburdened before the pandemic. Estimates of essential service disruption have largely come from the WHO PULSE survey distributed to all member states, which reports crude single informant estimates of disruption across four broad categories (from ‘not disrupted’ to ‘severely disrupted’). Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCAH) services were broadly reported as low to moderately affected by the pandemic across the Southeast Asia region (SEAR) in the PULSE Round 2 and 3 surveys. However, no comprehensive analysis of primary empirical evidence documenting the displacement of RMNCH services from the SEAR has been undertaken to date.

Added value of this study

We reviewed 1924 studies and analysed data from 20 peer-reviewed studies and three reports documenting quantitative estimates of RMNCH service disruption at before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We identified substantial disruption to antenatal care, facility-based deliveries, immunisation provision, paediatric health services, emergency obstetric care, and family planning services in six SEAR countries. There were no empirical studies of service disruption in the remaining five SEAR countries.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings highlight significant disruption to RMNCH services in six SEAR countries, often above 50% disruption, which is greater than PULSE survey estimates. There is a need for more empirical research to understand how RMNCH services have been impacted by the pandemic in other countries and in subsequent waves of infection to estimate immediate and potential long-term health and social impacts and to inform policies for reinstatement of essential services.

Introduction

Recognition of the COVID-19 pandemic as a global health emergency in January 2020 has placed enormous strain on the provision of essential health services globally.1, 2, 3, 4 Those who bear the highest burden of service disruption reside in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), where health systems may be less resilient to surges in demand.5, 6, 7 The UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) taskforce has highlighted mounting concerns that the pandemic has undermined reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health (RMNCH) targets globally and threatens to derail progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC).8

The WHO Southeast Asia region (SEAR) has experienced extremely high levels of COVID-19 disease burden and associated health system strain.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 This region comprises 11 socially, politically, economically, and geographically diverse member countries (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, People's Democratic Republic of Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Timor-Leste). These countries have made substantial strides towards UHC in recent decades, evidenced by substantial expansion of primary care services, government-sponsored health insurance and assurance programs, and preventive and curative care services.14,15 Marked progress has also been made in improving RMNCH outcomes and most SEAR countries were on track to attain the SDG 3 health targets related to RMNCH outcomes.

However, since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence has emerged that progress in RMNCH outcomes has slowed or even worsened for the first time in decades.8,16,17 The pandemic and the measures implemented to control it have significantly impacted progress towards UHC across the SEAR, setting many countries back against hard-fought gains.8,18 Several studies have reviewed the impact of the pandemic on RMNCH services in African countries, yet similar evidence syntheses for SEAR countries have not been conducted.19, 20, 21, 22 Furthermore, SEAR countries are underrepresented in recent global reviews on the pandemic's impact on health service provision23, 24, 25; thus, qualitative estimates of disruptions to essential health services, such as the WHO PULSE survey, provide important windows into which services were most negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic across the SEAR.

The WHO PULSE survey on the continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which informants from all WHO Member States were asked to estimate the level of service disruption across a range of approximately 25 services, was implemented across three rounds from 2020 to 2021.18,26,27 Nine SEAR countries responded to Rounds 2 (Q1, 2021) and 3 (Q4, 2022) (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Timor-Leste).26,27 Only the results from Round 3 are disaggregated by service and region. The most disrupted services included antenatal care (63% of the eight SEAR respondent countries reported a disruption of 5–25%), facility-based births, postnatal care, safe abortion (for which 50% reported a disruption of 26–50%), and “sick child services” (50% reported a disruption of more than 50%). Regarding immunisation, 38% of the eight respondent SEAR countries reported a disruption of 5–25% in routine facility-based services and 17% reported a disruption of 26–50% in outreach services. However, these findings have not been corroborated in the SEAR using primary empirical studies.

The identification, synthesis, and analysis of quantitative data to understand the true impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the provision and potential displacement of RMNCH services across SEAR are essential to support efforts to mitigate its impact, restore, and protect disease service provisions, and allocate resources accordingly. Here, we review the published quantitative evidence on the impact of COVID-19, compared to pre-pandemic data, on the provision of RMNCH services across the SEAR. Such research efforts have the potential to enhance our understanding of the impact of future public health emergencies on RMNCH services in the SEAR and can be utilised to inform policies for building more resilient health systems.

Methods

Approach and design of review

A systematic review was conducted to identify quantitative evidence detailing RMNCH service provision following the emergence of COVID-19 compared to pre-pandemic levels of service provision in each of the 11 WHO SEAR member countries. We followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement28 and prospectively submitted a systematic review protocol for registration on PROSPERO (CRD42022332130).

Search strategy

The detailed search strategy included all reasonable permutations in the three primary areas of interest: country/region (each of the SEAR countries), COVID-19, and RMNCH services (defined as services associated with prenatal care, perinatal care, postnatal care, neonatal and child healthcare, immunisation, or family planning). During June 1–30, 2022, three scientific databases were searched: PubMed, Embase (Ovid), and CINAHL (EBSCO). A manual search of reference lists and websites of multilateral organisations, with a focus on the RMNCH (Global Fund, UNICEF, GAVI, Save the Children, World Bank, and regional offices for the WHO and United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA]) was performed to identify relevant information. Studies published between December 2019, when the pandemic began, and May 2022, were considered for inclusion. For the specific database search strategies, please refer to Supplementary File 1.

Eligibility criteria

We included observational studies or commentaries that used any type of pre-post design to report primary comparative cross-sectional data on the provision of RMNCH services during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with that during periods before in one or more SEAR countries. Studies conducted in non-SEAR countries or those that reported only qualitative results were excluded, as were case reports, opinions, and clinical guidelines. Electronic citations, including the available abstracts of all articles retrieved from the search, were double-screened by two authors (TS and PP), with a third reviewer acting as an arbiter for any discrepancies (LD, TG, or DN) to select articles for full-text review. Duplicate samples were excluded from the initial search. Subsequently, full texts of potentially relevant studies were reviewed to determine their eligibility for inclusion. A full list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in Table 1. All articles identified in the searches were imported into the Covidence systematic review software (version 2; Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). Title and abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction were performed in Covidence.

Table 1.

Review protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria with examples.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Date range | Published at any time from December 2019 | Published prior to December 2019 |

| Population | Adult, newborn, and child populations in the WHO SEA Region | Countries outside of the WHO SEA Region |

| Study design | Comparative study designs that quantify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health response measures on health service provision | Qualitative studies, non-longitudinal studies, studies without comparison groups, opinions, letters, and clinical guidelines data |

| Conditions of interest | All types of reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) services | Other conditions not classified as RMNCH |

| Other | Published in English language | Published in language other than English |

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of the included empirical studies was evaluated using the eight-item Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional studies.29 The instrument was developed by the JBI and reviewed by an international methodological group. Quality appraisal was performed by a single reviewer (TG), and any points of uncertainty were addressed through discussion and consensus with a second reviewer (LD). We did not assess the risk of bias because our inclusion criteria were limited to study designs that were less prone to various potential biases. However, studies appraised as having low methodological quality were considered to have a high risk of bias.

Data extraction

Data were extracted in Covidence software using a standard template that was modified to include key parameters of interest (see Supplementary File 2). Information extracted from each paper included the following: country, setting, population of interest, service of interest, demographic details, data sources, and percentage change in service delivery metrics from pre-COVID to peri-COVID era. The following COVID-19 related information was also extracted from papers where possible: whether data collection coincided with a ‘peak’ of infection and/or lockdown; the wave with which the pandemic data collection coincided; whether any service protection/mitigation measures were in place during the period of data collection; the reported efficacy of the mitigation measures; and reported consequences of forgone or displaced health services because of COVID-19. Essential health services were divided into the following categories of interest, in line with patient population and pathways of care: antenatal care; postnatal care; paediatric care; immunisation; facility-based delivery; family planning and reproductive health; emergency obstetric care; neonatal intensive care; paediatric intensive care.

Evidence synthesis

Once data extraction was complete, the results were exported from Covidence into an Excel spreadsheet to support the evidence synthesis. Given the heterogeneity of the study settings, populations, conditions, and service areas, meta-analyses were not performed. A narrative synthesis was conducted following the ‘synthesis without meta-analysis (SWIM)’ in systematic review reporting guidelines30 to explore, describe, and interpret key findings related to the impact of COVID-19 on the provision of essential RMNCH services in the SEAR.

Role of the funding source

This study was funded by the WHO Sri Lanka (WHO-SL) Country Office. The funding agency had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. The WHO-SL Office reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Results

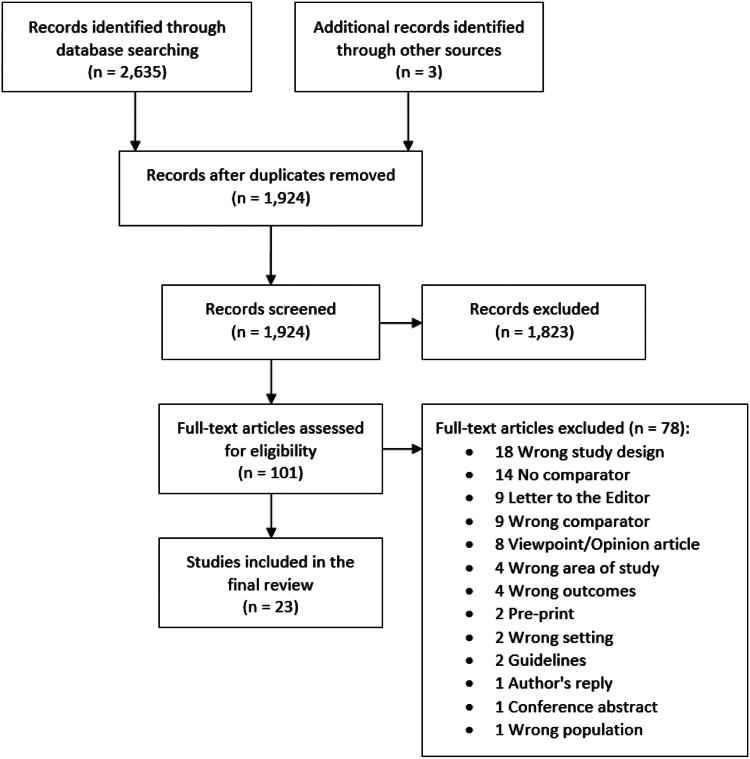

An initial 2635 papers were identified through a database search and four through grey literature. After duplicates were removed, 1924 records were retained for title and abstract screening based on the inclusion criteria. A total of 101 articles were relevant for full-text review, and 20 articles and three grey literature reports met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review (Fig. 1). Seventy-eight studies were excluded. The primary reasons for exclusion included incorrect study design (n = 18) (e.g. qualitative studies, surveys), non-comparative studies (n = 14) (i.e. primary data not compared to pre-pandemic period, e.g.31), letters to the editor (n = 9), opinion pieces (n = 8), and reporting on outcomes outside the scope of this review (n = 9). Two relevant studies were excluded as they were pre-printed.32,33

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram. Abbreviations: PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the 20 included studies and three grey literature reports.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 Four countries in the region were represented in the empirical literature (India [11 studies], Bangladesh [4], Nepal [4], and Sri Lanka [1]) and four in the grey literature (Bangladesh [3], Bhutan [1], Nepal [2], and Myanmar [1]). No studies were identified in Indonesia, North Korea, Maldives, Thailand, or Timor-Leste. All studies assessed the impact during the first wave of the pandemic (i.e. in 2020), and only one study was conducted during the second wave in 2021.49 The comparison periods were most commonly from a similar timeframe in the preceding year(s), with fewer studies reporting data on the months immediately prior to the pandemic response.

Table 2.

Studies included in the systematic review.

| First author, year | Country | Study design | Setting | Disease area | Sample size | Data collection period |

Quality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control period | Pandemic period | |||||||

| Ahmed 202134 | Bangladesh | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All facilities reporting to the HMIS (n = NR) | ANC; Childhood immunisation programs; Family planning; Emergency obstetric care | NR | March, 2019–April, 2019 | March, 2020–April, 2020 | Low |

| Arsenault 202235 | Nepal | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All facilities reporting to the HMIS (n = 7605) | ANC; Postnatal care; Childhood immunization programs; Facility-based delivery; Family planning | NR | Jan 15, 2019–March 2020 | March 2020–Jan 13, 2021 | Moderate |

| Ashish 202036 | Nepal | Prospective observational study | Nine hospitals (7 provincial, 2 district) | Facility-based delivery; Emergency obstetric care | 20,354 | Jan 1–Mar 20, 2020 | March 21–May 30, 2020 | High |

| Ashish 202137 | Nepal | Prospective observational study | Nine hospitals (7 provincial, 2 district) | Facility-based delivery; Postnatal care; | 52,356 | March–August 2019 | March–August 2020 | High |

| Golandaj 202238 | India | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All maternal and child services reporting to the HMIS | Paediatric TB notifications | NR | January to September 2019 | January–March 2020 and Mar 25–May 31, 2020, June to September 2020 | Low |

| Goyal 202139 | India | Facility record review | Single site, Jodhpur | ANC; Facility-based delivery | 1749 | Oct 1, 2019–Feb 29, 2020 | Apr 1–Aug 31, 2020 | Moderate |

| Hanifi 202140 | Bangladesh | Retrospective analysis (with extrapolation) | 49 villages in Chakaria upazila, Cox's Bazar District | Childhood immunisation programs | NR | Mar 1–May 31, 2018, 2019 | Mar 1–May 31, 2020 | Moderate |

| Hossain 2020a,41 | Bangladesh | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All public and private sector providers reporting to the HMIS | Family planning | NR | January–July 2019 | January–July 2020 | Low |

| Jayatissa 202142 | Sri Lanka | Prospective follow-up study | Urban settlements in Colombo | Child wasting, stunting | 236 | September 2019 | September 2020 | Moderate |

| Jha 202143 | Nepal | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All facilities reporting to the HMIS (n=>4000 facilities) | Facility-based delivery | NR | January 2020 | May 2020 | Low |

| Khan 202144 | India | Facility record review | Single site (tertiary hospital), New Delhi | Childhood immunization programs | NR | Jan 1–July 31, 2019 | Jan 1–July 31, 2020 | Low |

| Kinikar 202145 | India | Facility record review | Single site (tertiary hospital) | Childhood immunization programs | NR | Jan 1–Mar 24, 2020 | Mar 25–May 13, 2020 | Low |

| Kumari 202046 | India | Retrospective analysis | Four tertiary hospitals, Western India | Facility-based delivery; Emergency obstetric care | 9736 | Jan 15–Mar 24, 2020 | Mar 25–June 2, 2020 | Low |

| Kumari 202147 | India | Facility record review | Single site (tertiary hospital), North India | Facility-based delivery; Emergency obstetric care | 7630 | Oct 2019–March 2020 | April–September 2020 | Moderate |

| Mhajabin 202248 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional household survey | Baliakandi upazila, Rajbari District | ANC; Facility-based delivery | 555 | August–October 2019 | April–June 2020 | High |

| Nair 202149 | India | Primary quantitative data | 15 hospitals across five states (Assam, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Meghalaya). | Facility-based delivery; Family planning; Emergency obstetric care | 202,986 | December 2018–February 2020 | March–September 2020, October–February 2021, March–May 2021 | High |

| Naqvi 202250 | India | Prospective, population-based study | Two cities (Belagavi, Nagpur) | ANC; Facility-based delivery | 13,043 | March 2019–February 2020 | March 2020–February 2021 | High |

| Rana 202151 | Bangladesh | Primary quantitative data | Six upazilas, Barishal District | Childhood immunization programs | 73,916 | 2019 | 2020 | Low |

| Sarkar 202152 | India | Facility record review | Single site (tertiary hospital), West Bengal | ANC | 4189 | Jan 12–Mar 22, 2020 | Mar 23–May 31, 2020 | Moderate |

| Singh 202153 | India | Quasi-experimental design | One district (Sant Kabir Nagar, Uttar Pradesh) | ANC; Childhood immunization programs | NR | March–June 2019 | March–June 2020 | Moderate |

| UNFPA 2022a,54 | Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All facilities reporting to the HMIS | ANC; Facility-based delivery; Postnatal care visits | NR | February–May 2019 | February–May 2020; Aug 2020; Sept 2020; | Low |

| Vora 202055 | India | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All public sector facilities reporting to the HMIS | Family planning | NR | December 2019 | March 2020 | Low |

| WHO-UNICEF-UNFPA, 2021a,56 | Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nepal | Secondary analyses of HMIS data | All facilities reporting to the HMIS (n = NR) | ANC; Facility-based delivery | NR | March–April 2019 | March–April 2020 | Low |

Grey literature report; NR = not reported. Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; HMIS, health management information system; TB, tuberculosis.

Six studies reported exclusively on disruptions to childhood-related health services38,40,42,44,45,51 whereas 13 reported exclusively on maternal health-related services, including antenatal care visits, facility-based deliveries, emergency obstetric care, and family planning.36,37,39,43,46,48, 49, 50,52,55 Four studies reported disruptions in childhood and maternal health services.34,35,47,53 All studies were cross-sectional in nature, though different study design labels were applied, including “secondary analyses of routinely collected datasets” and retrospective case control.

Eight studies reported data from National Health Management Information Systems (HMIS),34,35,38,41,43,54, 55, 56 three studies were multisite studies, six focused on geographic areas (e.g. one district),40,42,48,50,51,53 and five were single-site studies (using hospital records). Three studies were commentary pieces that reported primary data.43,46,55 Sample sizes ranged from 236 to 202,986 (Table 2).

The scores for methodological quality were classified as low (scoring 1–4), moderate (5–6) or high (7–8). Of the 23 included studies, 11 were of low quality, seven moderate and five high. All studies clearly identified the exposure, condition, and outcome of interest; however, several analyses of the HMIS data failed to clearly report the sample size. Furthermore, the study sample characteristics were rarely described in detail. Only five studies adequately accounted for and addressed potential confounders in their analyses, primarily by reporting crude and adjusted estimates. The results of the quality assessment are presented in Supplementary File 3.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on maternal health services

Of the 14 studies that assessed the impact of the pandemic on maternal health services, eight were conducted in India, four in Nepal, and two in Bangladesh (Table 3). A change in the number of facility-based deliveries was the most common outcome reported (n = 9), with reductions ranging from 2.3% to 52.4%.34, 35, 36, 37,39,43,47,49,50,53 Five studies reported change in the number of caesarean procedures conducted, ranging from a decrease of 76.6% to an increase of 4%.34, 35, 36, 37,46,47 Five studies reported changes in the delivery of antenatal care (ANC) due to COVID-19 (reduction from 1.6% to 69.6%).34,35,48,50,52

Table 3.

Change in maternal health service provision by study.

| First author, year | Country | Outcome | Control period sample | Pandemic period sample | Percentage change (95% CI, p-value)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed 202134 | Bangladesh | Mothers received ANC | NR | NR | March 2020: −28.4%, April 2020: −56.9% |

| Attendance in family planning clinics | NR | NR | March 2020: −100.0%, April 2020: −100.0% |

||

| Vaginal deliveries | NR | NR | March 2020: −31.7%, April 2020: −57.6% |

||

| Caesarean section | NR | NR | March 2020: −50.0%, April 2020: −76.6% |

||

| Arsenault 202235 | Nepal | Antenatal care visits | 721 | NR | −20.9% (−34.2, −7.5) |

| Postnatal care visits | 128 | NR | −26.4% (−38.0, −14.7) | ||

| Facility-based delivery | 418 | NR | −11.6% (−18.8, −4.5) | ||

| Caesarean section | 87 | NR | −11.3% (−21.6, −0.9) | ||

| Family planning | 7148 | NR | −4.2% (−7.5, 0.9) | ||

| Ashish 202036 | Nepal | Total number of deliveries | 13,189 (64.8%) | 7165 (35.2%) | −45.7% |

| Mean weekly number of births | 1261.1 (SE 66.1) | 651.4 (49.9) | −52·4% | ||

| Caesarean section | 24.5% (n = 3234) | 26.2% (n = 1879) | +1.8% (p = 0·0075). | ||

| Institutional stillbirth rate | 14 per 1000 births | 21 per 1000 births | Adjusted risk ratio: 1.46 (1.13, 1.89) | ||

| Institutional neonatal mortality rate | 13 deaths per 1000 livebirths | 40 deaths per 1000 livebirths | Adjusted risk ratio: 3.15 (1.47, 6.74) | ||

| Ashish 202137 | Nepal | Mean number of institutional births | 27,793 | 24,563 | −11.6% (p < 0.0001) |

| Average bed occupancy rate in postnatal units | 91.0% (95% CI: 75.2, 106.8) | 81.8% (95% CI: 65.6, 97.9) | −9.2% (p = 0.421) | ||

| Goyal 202139 | India | Admissions | 1116 | 633 | −43.3% (p < 0.001) |

| Facility-based delivery | 1062 | 583 | −45.1% (p < 0.001) | ||

| High-risk pregnancies | 505 (45.3%) | 332 (52.5%) | +7.2% (p < 0.05) | ||

| Jha 202143 | Nepal | Facility-based delivery | 36,130 | 24,639 | −31.8% |

| Kumari 202046 | India | Referred obstetric emergencies |

905 | 304 | −66.4% |

| Caesarean section | 33% (of 6209) | 37.0% (of 3527) | +4.0% | ||

| Hospitalisation | 6209 | 3527 | −43.2% | ||

| Kumari 202147 | India | Vaginal deliveries | 2652 | 842 | −68.3% |

| Obstetric emergency admissions | 5806 | 1824 | −68.6% | ||

| Caesarean | 1552 | 623 | −59.9% | ||

| Mhajabin 202248 | Bangladesh | At least one ANC visit from a medical professional | 83% | 77% (pandemic period) | −6% (p > 0·05) |

| Birth attended by medical professional | 63% | 72% (early pandemic) | +9% (p > 0·05) | ||

| Nair 202149 | India | Facility-based delivery | 113,140 | 89,846 | Wave 1 rising −30% Wave 1 receding: −10% Wave 2 rising: −35% |

| Admission from septic abortion | Incidence rate per 1000 hospital births: 5.81 | Incidence rate per 1000 hospital births: 9.05 | +56% (1.22–1.99) (p < 0.001) | ||

| Naqvi 202250 | India | 4+ ANC visits | 78.4% (of 6701 women) | 76.8% (of 6342 women) | −1.6% (non-significant RR) |

| Facility-based physician delivery | 65.8% (of 6701 women) | 62.3% (of 6342 women) | −3.5% (non-significant RR) | ||

| Sarkar 202152 | India | ANC visit | 3212 | 977 | −69.6% (p < 0.001) |

| Singh 202153 | India | Received ANC | 1436 | 1107 | −22.9% |

| Facility-based delivery | NR | NR | −2.3% | ||

| Vora 202055 | India | IUD insertion | 260,615 | 205,395 | −21.2% |

| Injectable contraception, first dose | 66,112 | 42,639 | −35.5% |

Where available, p-values and 95% CI are reported. NR = not reported. Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; IUD, intrauterine device; OPD, outpatient department; RR, relative risk.

Substantial disruptions in facility-based deliveries were reported in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Ashish (2020) reported the highest decline based on data from nine referral hospitals across Nepal during Jan 1 to May 30, 2020.36,37 The average weekly reduction in hospital births during the lockdown was 7.4%, with a total decrease of 52.4% by the end of the lockdown. Furthermore, the utilisation of childbirth services decreased among disadvantaged ethnic groups and increased among advantaged groups. Jha and colleagues compared these estimates with routinely collected national data from the HMIS of Nepal, which included all types of institutional deliveries.43 They reported that the national institutional delivery rate fell by 31.8% (36,130 total births to 24,639) from January to May 2020, compared to 24.2% over the same period in 2019 (36,291–27,518). The largest comparative reductions occurred in April and May 2020 (8.8% and 11.7%, respectively), at the height of the national lockdown. Arsenault and colleagues examined Nepal's HMIS data and reported a 11.6% reduction in the number of facility-based deliveries, with the largest disruptions occurring in May 2020, although COVID-19 caseloads did not peak until October 2020.35

In India, Nair and colleagues analysed the longest period of interest by conducting repeated monthly surveys of maternal outcomes among 15 hospitals in five states from December 2018 to May 2021.49 Compared with the pre-pandemic period (Dec 2018–February 2020), hospital births decreased by 30% during the start of the first wave and by 35% during the second wave in May 2021, and hospital admissions due to septic abortion were 56% higher from Mar 2020 to May 2021. These findings had a statistically significant positive association with the Indian Government Response Stringency Index, a composite measure of the stringency of government prevention policies in response to COVID-19. Similar findings were reported by Goyal and colleagues, who found that the number of deliveries in a Jodhpur-based hospital fell by 45.1% over 5 months from April 1 to August 31, 2020 and the number of high-risk pregnancies increased by 7.2%.39 A study in a rural tertiary care centre in North India reported that the number of vaginal deliveries was 68.3% and obstetrical emergency admissions were 68.6% from April 2020 to September 2020 (compared to six months before the pandemic).47

Two studies also used HMIS data to examine reductions in ANC services. In Nepal, the provision of ANC services fell 20.9% (95% CI: −34.21, −7.53) during 2020 as compared to that in 2019,35 while in Bangladesh they fell by 28.4% in March 2020 and 56.9% in April 2020 compared to that in the same months in 2019.34 In India, a study by Sarkar and colleagues showed that ANC visits to the outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in West Bengal decreased by 69.6% (p < 0.001) during the first national lockdown.52 Sarkar and colleagues suggested that this was due to a combination of policy responses and demand-side factors, such as barriers imposed by the lockdown (e.g. no public transport), prioritising care for COVID-19 patients, and fear of contagion.35,52 In Uttar Pradesh, a study by Singh and colleagues showed that ANC services provided under specific government programs decreased by 22.9% from March to June 2020 (compared with that in the same timeframe in 2019).53 Finally, a much smaller reduction in ANC services was reported by Naqvi and colleagues (1.6%); however, this analysis included only mothers in two districts enrolled in a registry run by the Global Network for Women's and Children's Health Research.50

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on child health services

Nine studies assessed the disruptions in child health services, four of which were conducted in India, three in Bangladesh, one in Nepal, and one in Sri Lanka (see Table 4). The majority (n = 7) assessed the impact of the pandemic on the provision of childhood immunisation programmes.34,35,40,44,45,51,53 Others have assessed changes in the number of paediatric tuberculosis notifications38 as well as childhood wasting and stunting.42 All studies reported reductions in the provision of child immunisation services ranging from 13.5% to 87.7%.

Table 4.

Change in childhood-related service provision by study.

| First author, year | Country | Outcome | Control period sample | Pandemic period sample | Percentage change (95% CI, p-value)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed 202134 | Bangladesh | Children Vaccinated | NR | NR | March 2020: −13.5%, April 2020: −50.4% |

| Arsenault 202234 | Nepal | Childhood immunization programs | NR | NR | BCG: −45.7% (−58.3, −33.2) Pentavalent: −49.3% (−60.0, −38.6) Pneumococcal: −43.6% (−53.5, −33.7) MR: −49.0% (−60.7, −37.4) |

| Golandaj 202238 | India | Paediatric TB notifications | Pre-lockdown 2020: 5539 | Pre-lockdown 2020: 7334 | Pre-lockdown 2020: +32.4% |

| Lockdown 2020: 3888 | Lockdown 2020: 2953 Post- |

Lockdown 2020: −24.0% | |||

| Post-lockdown 2020: 9821 | Post-lockdown 2020: 6251 | Post-lockdown 2020: −36.4% | |||

| Hanifi 202140 | Bangladesh | Monthly immunization outreach sessions | In 2019, 99% of 86 monthly outreach sessions conducted | March 2020: 74% conducted | March 2020: −26% |

| April 2020: 10% conducted | April 2020: −90% | ||||

| May 2020: 3% conducted | May 2020: −97% | ||||

| Jayatissa 202142 | Sri Lanka | Wasting prevalence | 15/109 (13.7%) | 20/109 (18.3%) | +4.6% (p > 0·05) |

| Stunting prevalence | 13/109 (11.9%) | 16/109 (14.7%) | −2.8% (p > 0·05) | ||

| Khan 202144 | India | Mean total vaccine count | 1311.14 (range: 932–1480) | 1051 (range: 356–1803) | April 2020: −87.7% (p < 0.001) |

| May 2020: −67% | |||||

| June 2020: −33% | |||||

| July 2020: +27% (p = 0.228) | |||||

| Kinikar 202145 | India | Mean number of childhood vaccinations per week | OPV: 86.1 | OPV: 30.8 | OPV: −55.3 |

| Pentavalent: 67.7 | Pentavalent: 24.8 | Pentavalent: −42.9 | |||

| Rota vaccine: 64.8 | Rota vaccine: 24.0 | Rota vaccine: −40.8 | |||

| IPV: 46.6 | IPV: 18.4 | IPV: −28.2 | |||

| MR: 29.6 | MR: 10.9 | MR: −18.7 | |||

| Rana 202151 | Bangladesh | Childhood immunization programs | 2019: 16,524 | 2020: 15,505 | −6.2% |

| April–May 2019: 2746 | April–May 2020: 2183 | −20.5% | |||

| July–October 2019: 5562 | July–October 2020: 5561 | 0% | |||

| Singh 202153 | India | Childhood immunization programs | NR | NR | BCG −12.2% OPV −24.6% MR 1st −28.0% JE −28.3% MR 2nd −31.6% TD −20.8% |

Where available, p-values and confidence intervals are reported. NR = not reported. Abbreviations: BCG, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; JE, Japanese encephalitis; MR, measles rubella; OPV, Oral poliovirus vaccine; TD, Tetanus and Diphtheria.

In Bangladesh, two studies used HMIS data to assess immunisation disruptions. Ahmed and colleagues reported that the number of children receiving measles and rubella vaccines had decreased by 13.5% in March 2020 and 50.4% in April 2020.34 In six upazilas (subdistricts), Rana and colleagues reported that 20.5% of planned monthly immunisation outreach sessions were cancelled from April to May 2020, yet on average 99% were conducted from June to October 2020.51 Hanifi and colleagues assessed the same outcome for one rural upazila in Bangladesh using data from the Health and Demographic Surveillance System and reported that outreach sessions declined by 26.6%, 89.6%, and 96.6% (vs. 2019 levels) in March, April, and May 2020, respectively.40

Three studies assessed immunisation disruptions during India's first lockdown (Mar 25–May 13, 2020). Khan and colleagues analysed the longest period of interest (January–July 2020) and observed a complete suspension of immunisation services in April 2020, with only birth doses such as hepatitis B vaccine, BCG, and oral polio vaccine (OPV) being administered.44 Despite the increasing number of COVID-19 cases, the immunisation rate improved in May and June 2020, and catch-up was underway by July 2020. Studies by Kinikar and colleagues, and Singh and colleagues assessed the impact of the national lockdown on immunization coverage and reported reductions of up to 55.3% for the oral polio vaccine, 42.9% for the pentavalent vaccine, 40.8% for the rotavirus vaccine, and 28.0% and 31.6% for the first and second dose of the measles-rubella vaccine, respectively.45,53

Grey literature

Information obtained from the three grey literature sources is presented in Table 5.41,54,56 Using national service statistics, the Population Council (2020) reported substantial disruptions in the provision of contraceptive methods in Bangladesh, with the sharpest decline occurring immediately after the lockdown began (April 2020), and gradually improving by July 2020.41 The WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA (2021) jointly conducted a rapid survey on the delivery of RMNCH services from March–April 2020 based on national HMIS data.56 Substantial reductions in ANC provisions and facility-based deliveries were reported in Bangladesh and Nepal, with less of an impact on Myanmar. Bhutan, DPR Korea, Indonesia, and Timor-Leste reported no changes in these outcomes; Thailand did not participate. Finally, the United Nations Population Fund (2022) assessed RMNCH service reductions in the Asia–Pacific region from Februaryruary to May 2020 and found substantial reductions in Bangladesh; however, the data provided for Bhutan and Nepal were less clear.54

Table 5.

Change in family planning, antenatal care, facility-based deliveries, and postnatal care in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, and Nepal.

| First author, year | Country | Control time period | Pandemic time period | Health service | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hossain, 202041 | Bangladesh | April 2019 | April 2020 | Distribution of family planning methods (condoms, injectables, intrauterine devices, and implants) | −30% to −100% |

| UNFPA, 202254 | Bangladesh | February–May 2019 | February–May 2020 | ANC in facilities | −57% |

| Facility-based deliveries | −35% | ||||

| Postnatal care visits | −50% | ||||

| Bhutan | NR | August 2020 | ANC in facilities | ∼−25% | |

| Facility-based deliveries | no change | ||||

| Postnatal care visits | ∼−25% | ||||

| Nepal | NR | September 2020 | Key RMNCAH services | −22 to −34% | |

| WHO-UNICEF-UNPFA, 202156 | Bangladesh | March–April 2019 | March–Apr il 2020 | ANC in facilities | −41% |

| April–May 2019 | April–May 2020 | Facility-based deliveries | −31% | ||

| Myanmar | March–April 2019 | March–April 2020 | ANC in facilities | −6%, −3.5% | |

| March 2019 | March 2020 | Facility-based deliveries | −0.9% | ||

| Nepal | March–April 2019 | March–April 2020 | ANC (1 visit) | −45.5% | |

| ANC (4 visits) | −52% | ||||

| Facility-based deliveries | −58.7% |

Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; WHO, World Health Organization; RMNCAH, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health; UNFPA, United Nations Population Fund; UNICEF, United Nations Childrens fund.

Discussion

This systematic review summarises the available empirical quantitative data from SEAR member countries regarding the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on essential RMNCH service provisions. We identified substantial disruptions to antenatal care, facility-based deliveries, immunisation provision, emergency obstetric care, and family planning services, primarily during the first wave of the pandemic in 2020, in three SEAR countries (India, Bangladesh, and Nepal) with limited data from Bhutan, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka. Notably, we highlight a higher level of RMNCH service disruption than that reported in Rounds 2 and 3 of the WHO PULSE survey. However, only one study examined service disruptions from the first wave of the pandemic to 2021, thereby precluding any assessment of longitudinal trends in service disruptions as the pandemic progressed.

Notably, greater levels of disruption were reported in this review than that in the Rounds 2 and 3 of the WHO PULSE survey. Given the methodology adopted for PULSE, it is plausible that key informants were operating with ordinal response categories lacking the variation captured in these studies, particularly in cases where studies referred to subnational scales (i.e. disruption in a set of hospitals or from locations or facilities reporting to a database). Moreover, 11 of the 23 studies were from India, which did not participate in the PULSE process. Unfortunately, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis because of varying indicator definitions, a lack of matched time periods, and a lack of information on sampling methods and population sizes. More research is needed to understand the reasons for this disparity, which could reflect underreporting in PULSE or high variation in service disruptions across and within contexts during this time, particularly in India.

While our findings align with recent reviews, evidence from SEAR countries is largely underrepresented in these reviews. For instance, a global review and meta-analysis reported reduced maternity care provision due to the pandemic (e.g. ANC appointments fell by 38.6%); however, only three of 56 studies were from the SEAR.25 The same applies to other recent reviews, questioning their generalisability to the region.23,24 The relatively high number of SEAR-specific studies included in our review may be explained by the inclusion of the name of each country in our search strategy and the large number of studies emerging from India. Nevertheless, our findings are in line with a simulation study that specifically focused on the south Asian region, which found that in the second quarter of 2020, the coverage of all essential RMNCH services declined substantially, often above 50%.57

Studies have cited a range of demand-side barriers to access, primarily related to national lockdowns, such as movement restrictions and public transport shutdowns, the redeployment of health workers or hospitals to COVID-19 care, the inability to pay for healthcare due to loss of employment or remuneration, fear of infection, and the threat of prosecution from being found in a public place without permission. This aligns with recent qualitative analyses.58, 59, 60 Other published evidence has also shed light on the myriad supply side factors that negatively impact the provision of essential healthcare services, including staff absenteeism; shortages in medicines and health supplies; and pivoting for human resources, supplies, and infrastructure for COVID-19 cases.61,62 The negative impact of these barriers was demonstrated immediately with reductions in antenatal care, facility-based deliveries, immunisation provisions, and elevated rates of high-risk pregnancies. These disruptions have contributed to increased child and maternal mortality rates16,17; In Bangladesh, for example, child mortality is estimated to have increased by 14.9% and maternal mortality by 3.9% from March 2020 to June 2021.63

The interpretation of the findings from our review is limited by the retrospective design of the included studies, the heterogeneity of study populations and settings, and the time frame within which the study was undertaken. In the absence of adequate service coverage in pre-pandemic periods, the interpretation of disruptions based purely on the pre-pandemic/post -pandemic onset data must be approached with caution. For instance, the magnitude of disruption in Myanmar appears to be low but may reflect a lack of access during pre-pandemic periods. While Thailand may have emerged as a country with minimal service disruption during the period assessed, recent evidence suggests that migrant populations may have experienced disruptions in vaccination services.64 Such information on differential impacts across population subgroups and sexes has rarely been reported and requires further analysis to shed light on the equity dimensions of service disruption.

Overall, there is a dearth of high-quality population-representative data for all services across SEAR countries. In theory, the use of national health management information systems should capture representative data; however, the quality constraints of such systems in LMICs are well documented and may have been exacerbated during the pandemic.65,66 Furthermore, many studies were single-site record reviews, limiting generalisability to the wider population. For these reasons, the reported data likely only reflect utilisation patterns in the public sector, and the negative impacts observed are likely under-reported, considering that most studies rarely include community-based reporting of RMNCH outcomes. We also cannot exclude the risk of underreporting in peer-reviewed and international media, and therefore missing country-level data of relevance, due to the public inaccessibility of national government reports and our search strategy targeting only studies published in the English language. Nonetheless, the focus on quantitative pre-pandemic/post -pandemic onset empirical data is also a strength of this study, given the lack of existing synthesis of local evidence for the region.

The small number of studies conducted outside India and the dearth of relevant studies in Bhutan, Indonesia, North Korea, Maldives, Thailand, and Timor-Leste limit the generalisability of our conclusions to SEAR. While the absence of studies from Bhutan and Timor-Leste is unsurprising considering that they have been relatively unaffected by the pandemic, the lack of studies from Indonesia, Thailand, and the Maldives is notable. Previous reviews of the disruptions caused by the pandemic in Southeast Asia have faced similar challenges in identifying studies from these countries.67,68 Therefore, it is imperative to conduct high-quality research to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on the provision of essential healthcare services in these countries.

Designing effective measures to safeguard access to RMNCH services during public health emergencies requires mapping the specific causes driving disruptions. In this review, our findings suggest national lockdowns, strict mobility restrictions, fear of infection, and supply side limitations were at play. Although our review only provides data on the first wave of the pandemic, these issues continue to hamper service access and utilisation during subsequent waves (particularly during the delta variant of SARS-CoV-2).69,70 Potential mitigation strategies include transport or ambulance services for pregnant women during periods of lockdown, active public health messaging that urges women to seek the required reproductive health care, restructuring ANC services to leverage telehealth avenues, continuity of community health worker services, and human resource capacity building to ensure compliance with international and national guidelines for frontline health workers.17,20,22,71,72 The use of such strategies to address access barriers must be highly contextualised and integrated as a core component of future pandemic response and planning.

In summary, this systematic review found that the COVID-19 pandemic caused large disruptions to the provision of RMNCH services in the SEAR, primarily in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, during the first wave of 2020. Notably, we found a higher level of service disruption than that reported in the WHO PULSE survey for Rounds 2 and 3. If left unaddressed, such disruptions may set back hard-fought gains in RMNCH outcomes across region. The lack of studies in other SEAR countries is a priority evidence gap that needs to be addressed to better inform service protection policies. A number of policies were put in place during the pandemic period73; their operationalisation and impact on RMNCH outcomes across population subgroups also requires evaluation.

Contributors

Conception or design of the work: LD, DN, DP, TG; Data collection: TS, PP, TG, LD, DN; Data analysis and interpretation: LD, TG, DN, DP; Drafting the article: TG, LD, DN; Critical revision of the article: DP,LD,DN.

Data sharing statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Declaration of interests

This work was supported by the WHO Sri Lanka Country office (payment made to institution). TG is supported by a University Postgraduate Award from the University of New South Wales. DP is supported by a NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship. TS was supported by the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Scholarship and was awarded T. Russell Wilkins Memorial Scholarship and Global Experience Award by McMaster University. DN was supported by the India Alliance Fellowship (IA/CPHI/16/1/502,653, salary support) and received consulting fees from Department of Data and Analytics-WHO (included guest editorship of a special issue on COVID-19 and inequality). LD received £500 on three separate occasions for delivering lectures to Kings college London (2022, 2021) and Imperial college London (2022), and is an expert member of the health economics advisory group to the UK Infected Blood Inquiry (2020–2022) [no payment was received]. Authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the WHO Sri Lanka Country Office for constructive comments and guidance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2024.100357.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Gupta N., Dhamija S., Patil J., Chaudhari B. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30(Suppl 1):S282–S284. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.328830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan A.B., Jewell B.L., Sherrard-Smith E., et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1132–e1141. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30288-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lal A., Lim C., Almeida G., Fitzgerald J. Minimizing COVID-19 disruption: ensuring the supply of essential health products for health emergencies and routine health services. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;6:100129. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murewanhema G., Madziyire M.G. COVID-19 restrictive control measures and maternal, sexual and reproductive health issues: risk of a double tragedy for women in sub-Saharan Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;40:122. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.122.27946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma X., Vervoort D., Reddy C.L., Park K.B., Makasa E. Emergency and essential surgical healthcare services during COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries: a perspective. Int J Surg. 2020;79:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Josephson A., Kilic T., Michler J.D. Socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 in low-income countries. Nat Human Behav. 2021;5(5):557–565. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueroa J.P., Bottazzi M.E., Hotez P., et al. Urgent needs of low-income and middle-income countries for COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics. Lancet. 2021;397(10274):562–564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00242-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations . 2022. 2022 sustainable development goals progress report.https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amul G.G., Ang M., Kraybill D., Ong S.E., Yoong J. Responses to COVID-19 in southeast Asia: diverse paths and ongoing challenges. Asian Econ Pol Rev. 2022;17(1):90–110. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baniasad M., Mofrad M.G., Bahmanabadi B., Jamshidi S. COVID-19 in Asia: transmission factors, re-opening policies, and vaccination simulation. Environ Res. 2021;202 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chookajorn T., Kochakarn T., Wilasang C., Kotanan N., Modchang C. Southeast Asia is an emerging hotspot for COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1495–1496. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fauzi M.A., Paiman N. COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Asia: intervention and mitigation efforts. Asian Educ Dev Stud. 2021;10(2):176–184. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vineet B., Partha Pratim M., Srinath S., Tjandra Yoga A., Mukta S. Mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on progress towards ending tuberculosis in the WHO South- East Asia Region. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2020;9(2):95–99. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.294300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chongsuvivatwong V., Phua K.H., Yap M.T., et al. Health and health-care systems in Southeast Asia: diversity and transitions. Lancet. 2011;377(9763):429–437. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61507-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Minh H., Pocock N.S., Chaiyakunapruk N., et al. Progress toward universal health coverage in ASEAN. Glob Health Action. 2014;7 doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvert C., John J., Nzvere F.P., et al. Maternal mortality in the covid-19 pandemic: findings from a rapid systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(sup1) doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1974677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chmielewska B., Barratt I., Townsend R., et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e759–e772. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2020. Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adu P.A., Stallwood L., Adebola S.O., Abah T., Okpani A.I. The direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child health services in Africa: a scoping review. Glob Health Res Policy. 2022;7(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s41256-022-00257-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aranda Z., Binde T., Tashman K., et al. Disruptions in maternal health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: experiences from 37 health facilities in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murewanhema G., Mpabuka E., Moyo E., et al. Accessibility and utilization of antenatal care services in sub-Saharan Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. Birth. 2023;50(3):496–503. doi: 10.1111/birt.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapira G., Ahmed T., Drouard S.H.P., et al. Disruptions in maternal and child health service utilization during COVID-19: analysis from eight sub-Saharan African countries. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36(7):1140–1151. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czab064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.VanBenschoten H., Kuganantham H., Larsson E.C., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to and utilisation of services for sexual and reproductive health: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee T.I., Khan A.G., Dasgupta A., Samari G. Reproductive justice in the time of COVID-19: a systematic review of the indirect impacts of COVID-19 on sexual and reproductive health. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):252. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01286-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Townsend R., Chmielewska B., Barratt I., et al. Global changes in maternity care provision during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;37 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . WHO; 2021. Second round of the national pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: January-March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . WHO; 2022. Third round of the global pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: November–December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moola S., Munn Z., Sears K., et al. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): the Joanna Briggs Institute's approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):163–169. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell M., McKenzie J.E., Sowden A., et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helmyati S., Dipo D.P., Adiwibowo I.R., et al. Monitoring continuity of maternal and child health services, Indonesia. Bull World Health Organ. 2022;100(2):144–154a. doi: 10.2471/BLT.21.286636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh M., Puri M., Chaudhary V., et al. Preprint; 2022. Impact of Covid 19 pandemic on maternofetal outcome in pregnant women with severe anemia: a retrospective case control study. Authorea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pokharel A., Kiriya J., Shibanuma A., Silwal R., Jimba M. Association of workload and practice of respectful maternity care among the healthcare providers, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in south western Nepal: a cross-sectional study. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.02.21.22271309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed T., Rahman A.E., Amole T.G., et al. The effect of COVID-19 on maternal newborn and child health (MNCH) services in Bangladesh, Nigeria and South Africa: call for a contextualised pandemic response in LMICs. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:77. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01414-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arsenault C., Gage A., Kim M.K., et al. COVID-19 and resilience of healthcare systems in ten countries. Nat Med. 2022;28(6):1314–1324. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01750-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashish K.C., Gurung R., Kinney M.V., et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(10):e1273–e1281. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashish K.C., Peterson S.S., Gurung R., et al. The perfect storm: disruptions to institutional delivery care arising from the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. J Glob Health. 2021;11 doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golandaj J.A. Pediatric TB detection in the era of COVID-19. Indian J Tuberc. 2022;69(1):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goyal M., Singh P., Singh K., Shekhar S., Agrawal N., Misra S. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal health due to delay in seeking health care: experience from a tertiary center. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;152(2):231–235. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanifi S.M.A., Jahan N., Sultana N., Hasan S.A., Paul A., Reidpath D.D. Millions of Bangladeshi children missed their scheduled vaccination amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.738623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hossain M.I., Hossain M.S., Ainul S., et al. Population Council; Dhaka: 2020. Trends in family planning services in Bangladesh before, during and after COVID-19 lockdowns: evidence from national routine service data. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jayatissa R., Herath H.P., Perera A.G., Dayaratne T.T., De Alwis N.D., Nanayakkara H. Impact of COVID-19 on child malnutrition, obesity in women and household food insecurity in underserved urban settlements in Sri Lanka: a prospective follow-up study. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(11):3233–3241. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021001841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jha D., Adhikari M., Gautam J.S., Tinkari B.S., Mishra S.R., Khatri R.B. Effect of COVID-19 on maternal and neonatal services. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e114–e115. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30482-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan A., Chakravarty A., Mahapatra J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on childhood immunization in a tertiary health-care center. Indian J Community Med. 2021;46(3):520–523. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_847_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kinikar A.A. 2021. Impact of covid-19 lockdown on immunization at a public tertiary care teaching hospital. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumari V., Mehta K., Choudhary R. COVID-19 outbreak and decreased hospitalisation of pregnant women in labour. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1116–e1117. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumari K., Kumar D., Mittal N., et al. Covid-19 pandemic and decreased obstetrical emergency admissions - study at rural tertiary care center in north India. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2021;8(3):3346–3352. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mhajabin S., Hossain A.T., Nusrat N., et al. Indirect effects of the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on the coverage of essential maternal and newborn health services in a rural subdistrict in Bangladesh: results from a cross-sectional household survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nair M., Maat H.R.I.W.G., On Behalf Of The Maat H.R.I.C. Reproductive health crisis during waves one and two of the COVID-19 pandemic in India: incidence and deaths from severe maternal complications in more than 202,000 hospital births. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naqvi S., Naqvi F., Saleem S., Thorsten V.R., Figueroa L., Mazariegos M. Health care in pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic and pregnancy outcomes in six low- and-middle-income countries: evidence from a prospective, observational registry of the global network for women's and children's health. BJOG. 2022;129(8):1298–1307. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rana S., Shah R., Ahmed S., Mothabbir G. Post-disruption catch-up of child immunisation and health-care services in Bangladesh the lancet. Infect Dis. 2021;21(7):913. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00148-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkar S., Chowdhury R.R., Mukherji J., Samanta M., Bera G. Comparison of attendance of patients pre-lockdown and during lockdown in gynaecology and antenatal outpatient department in a tertiary care hospital of Nadia, West Bengal, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2021;15(2):QC05–QC08. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh A.K., Jain P.K., Singh N.P., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child health services in Uttar Pradesh, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(1):509–513. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1550_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.United Nations Population Fund Asia Pacific Regional Office . Bangkok UNFPA; 2022. Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response systems in asia-pacific during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020-2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vora K.S., Saiyed S., Natesan S. Impact of COVID-19 on family planning services in India. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(1) doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1785378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia . WHO; New Delhi: 2021. Impact of covid-19 on srmncah services, regional strategies, solutions and innovations: a comprehensive report. [Google Scholar]

- 57.UNICEF . UNICEF; Nepal: 2021. Direct and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and response in South Asia. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sigdel A., Bista A., Sapkota H., Teijlingen E.V. Barriers in accessing family planning services in Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2023;18(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anggraeni M.D., Setiyani R., Triyanto E., Iskandar A., Nani D., Fatoni A. Exploring the antenatal care challenges faced during the COVID-19 pandemic in rural areas of Indonesia: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05495-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma S., Aggarwal S., Kulkarni R., et al. Challenges in accessing and delivering maternal and child health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional rapid survey from six states of India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1538. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hazfiarini A., Akter S., Homer C.S., Zahroh R.I., Bohren M.A. ‘We are going into battle without appropriate armour’: a qualitative study of Indonesian midwives' experiences in providing maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women Birth. 2022;35(5):466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Razu S.R., Yasmin T., Arif T.B., et al. Challenges faced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry from Bangladesh. Front Public Health. 2021;9:647315. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.647315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ahmed T., Roberton T., Vergeer P., et al. Healthcare utilization and maternal and child mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in 18 low- and middle-income countries: an interrupted time-series analysis with mathematical modeling of administrative data. PLoS Med. 2022;19(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gilder M.E., Pateekhum C., Hashmi A., et al. Who is protected? Determinants of hepatitis B infant vaccination completion among a prospective cohort of migrant workers in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01802-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ayele W., Gage A., Kapoor N.R., et al. Quality of routine health data at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia, Haiti, Laos, Nepal, and South Africa. Popul Health Metrics. 2023;21(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12963-023-00306-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turcotte-Tremblay A.M., Leerapan B., Akweongo P., et al. Tracking health system performance in times of crisis using routine health data: lessons learned from a multicountry consortium. Health Res Policy Syst. 2023;21(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12961-022-00956-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gadsden T., Downey L.E., Vilas V.D.R., Peiris D., Jan S. The impact of COVID-19 on essential health service provision for noncommunicable diseases in the South-East Asia region: a systematic review. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2022;1 doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Downey L.E., Gadsden T., Vilas V.D.R., Peiris D., Jan S. The impact of COVID-19 on essential health service provision for endemic infectious diseases in the South-East Asia region: a systematic review. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2022;1 doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2022.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rayamajhee B., Pokhrel A., Syangtan G., et al. How well the government of Nepal is responding to COVID-19? An experience from a resource-limited country to confront unprecedented pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.597808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malik M.A. Fragility and challenges of health systems in pandemic: lessons from India's second wave of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Global Health J. 2022;6(1):44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ekawati F.M., Muchlis M., Ghislaine Iturrieta-Guaita N., Astuti Dharma Putri D. Recommendations for improving maternal health services in Indonesian primary care under the COVID-19 pandemic: results of a systematic review and appraisal of international guidelines. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2023;35 doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2023.100811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raina N., Khanna R., Gupta S., Jayathilaka C.A., Mehta R. Behera SProgress in achieving SDG targets for mortality reduction among mothers, newborns, and children in the WHO South-East Asia Region. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023;18 doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2021. Maintaining the provision and use of services for maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and older people during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from 19 countries. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.