Abstract

Background and objectives

Low circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and high sodium intake are both associated with progressive albuminuria and renal function loss in CKD. Both vitamin D and sodium intake interact with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. We investigated whether plasma 25(OH)D or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D] is associated with developing increased albuminuria or reduced renal function and whether these associations depend on sodium intake.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Baseline plasma 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D were measured by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, and sodium intake was assessed by 24-hour urine collections in the general population–based Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease cohort (n=5051). Two primary outcomes were development of urinary albumin excretion >30 mg/24 h and eGFR (creatinine/cystatin C–based CKD Epidemiology Collaboration) <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Participants with CKD at baseline were excluded. In Cox regression analyses, we assessed associations of vitamin D with developing increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR and potential interaction with sodium intake.

Results

During a median follow-up of 10.4 (6.2–11.4) years, 641 (13%) participants developed increased albuminuria, and 268 (5%) participants developed reduced eGFR. Plasma 25(OH)D was inversely associated with increased albuminuria (fully adjusted hazard ratio [HR] per SD higher, 0.86; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.78 to 0.95; P=0.003) but not reduced eGFR (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.87 to 1.12; P=0.85). There was interaction between 25(OH)D and sodium intake for risk of developing increased albuminuria (P interaction =0.03). In participants with high sodium intake, risk of developing increased albuminuria was inversely associated with 25(OH)D (lowest versus highest quartile: adjusted HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.73, P<0.01), whereas this association was nonsignificant in participants with low sodium intake (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.77; P=0.12). Plasma 1,25(OH)2D was not significantly associated with increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR.

Conclusions

Low plasma 25(OH)D is associated with higher risk of developing increased albuminuria, particularly in individuals with high sodium intake, but not of developing reduced eGFR. Plasma 1,25(OH)2D is not associated with risk of developing increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR.

Keywords: 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; vitamin D; sodium; diet; chronic kidney disease; albuminuria; eGFR; creatinine; cystatin C; follow-up studies; humans

Introduction

The current prevalence of CKD in the United States is estimated at 14% and has increased by 2% over the past two decades (1). Early diagnosis and treatment or, ideally, prevention of CKD are likely to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events and renal failure and the high CKD–associated costs. Therefore, it is crucial to identify modifiable factors affecting the development of CKD.

Vitamin D deficiency, usually defined as a 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] level <15 or 20 ng/ml (<37 or 50 nmol/L) (2), is common in CKD and has been associated with increased albuminuria and progressive renal function loss (3–5). The 25-hydroxylation of vitamin D is mainly substrate dependent; consequently, circulating levels of 25(OH)D are used to determine vitamin D status. In the second hydroxylation step, 25(OH)D is converted into the biologically active form 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D] by 1α-hydroxylase, which is predominantly but not exclusively expressed in renal proximal tubular cells. A previous study suggested that 25(OH)D deficiency is associated with increased albuminuria (6). Whether 1,25(OH)2D is associated with CKD development is unknown.

Vitamin D may influence the course of CKD by crosstalk with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) (7). Moreover, several lines of evidence suggest interaction between the renal effects of vitamin D deficiency and sodium intake. High dietary sodium intake adversely affects albuminuria levels and glomerular hemodynamics, even independent of BP, and induces renal fibrosis (8–11), which might be related to activation of the intrarenal RAAS (12). Furthermore, recent studies suggest an interaction between sodium intake and the antialbuminuric efficacy of vitamin D receptor (VDR) activator treatment (13,14).

We therefore prospectively investigated whether 25(OH)D or 1,25(OH)2D levels are associated with the risk of developing increased albuminuria or reduced renal function and whether these associations depend on sodium intake in a general population–based cohort with long–term follow-up.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This study was performed using data of the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease (PREVEND; http://www.prevend.org) cohort, a large prospective population–based cohort investigating albuminuria and renal and cardiovascular diseases. Details of this study have been described elsewhere (15,16). In summary, from 1997 to 1998, all inhabitants of Groningen, The Netherlands, ages 28–75 years old (n=85,421) received a questionnaire and a vial to collect a first morning void urine sample. Pregnant women and patients with type I diabetes mellitus were excluded. Some participants in whom existence of type II diabetes was newly discovered at the PREVEND Study screening were included. Urinary albumin concentration (UAC) was assessed in 40,856 responders. Participants with a UAC>10 mg/L (n=7768) were invited to participate, of whom 6000 were enrolled. In addition, a randomly selected group with a UAC<10 mg/L (n=3394) was invited to participate, of whom 2592 enrolled. In this study sample, 1928 participants (38%) had UAC≤10 mg/L, whereas 3122 participants (62%) had UAC>10 mg/L. The PREVEND Study was approved by the Institutional Medical Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

For this study, we excluded participants with missing data on 25(OH) or 1,25(OH)2D (n=661), serum creatinine, serum cystatin, urinary albumin excretion (UAE; n=397), or urinary sodium excretion (n=31) at baseline; with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or albuminuria >30 mg/24 h at baseline (n=1236); who were on vitamin D analogs, lithium, or thyroid therapy at baseline (n=132); or with no follow-up data on kidney function (n=1084), leaving 5051 participants for the analyses. Each examination included two outpatient clinic visits separated by 3 weeks.

Data Collection

Before the first visit, all participants completed a self-administered questionnaire regarding demographics, cardiovascular and renal disease history, smoking habits, and medication use. Information on medication use was combined with information from a pharmacy-dispensing registry. Weight and height were measured at the outpatient clinic, and BP was measured by an automatic Dinamap. The mean of the last two recordings from each visit was used. The week before the second baseline visit, participants collected 24-hour urine twice on 2 consecutive days. Participants were instructed to postpone urine collection in case of urinary tract infection, menstruation, or fever. Urine specimens were stored at −20°C. Furthermore, fasting blood samples were taken and stored at −80°C. Type II diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose >7.0 mmol/L, nonfasting plasma glucose >11.1 mmol/L, or use of antidiabetic drugs.

Albuminuria and eGFR Ascertainment

Albuminuria was calculated as the average from two consecutive 24-hour urine collections. eGFR was calculated on the basis of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation combining creatinine and cystatin C (17). The primary outcomes were either new-onset albuminuria >30 mg/24 h or eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Laboratory Measurements

Circulating 25(OH) and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 levels were measured in baseline plasma samples using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, with intra- and interassay coefficients of variation for 25(OH)D of 7.2% and 6.7%, respectively, and for 1,25(OH)2D of 5.0% and 14.1%, respectively. UAC was determined by nephelometry (BNII; Dade Behring Diagnostic, Marburg, Germany), with a threshold of 2.3 mg/L and intra- and interassay coefficients of variation of 2.2% and 2.6%, respectively. Serum creatinine was measured by an enzymatic method on a Roche Modular Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany; intra- and interassay coefficients of variation, 0.9% and 2.9%, respectively). Serum cystatin C concentrations were determined by Gentian Cystatin C Immunoassay (Gentian AS, Moss, Norway) on a Roche Diagnostics Modular autoanalyzer. Cystatin C was calibrated using the standard supplied by the manufacturer (traceable to the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry Working Group for Standardization of Serum Cystatin C). Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were <4.1% and <3.3%, respectively. Urinary sodium concentration was determined with an MEGA Clinical Chemistry Analyzer (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Urinary sodium excretion was calculated as the average value from two consecutive 24-hour urine collections. Other laboratory measurements have been described before (18).

Statistical Analyses

The study population was subdivided into four groups according to baseline 25(OH)D level (above versus below the median) and baseline urinary sodium excretion. High sodium represented the third tertile of sodium excretion, whereas low sodium represented the first and second tertiles of sodium excretion, in line with our prespecified hypothesis that high sodium intake interacts with the association between vitamin D status and increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR. Differences between categories were assessed with ANOVA for normally distributed continuous data, Kruskal–Wallis test for skewed data, and chi-squared test for nominal data.

To examine the prospective association between baseline vitamin D status and risk of developing increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR, we performed Cox proportional hazards regression models. Because the PREVEND Study is enriched with the presence of an elevated UAC (>10 mg/L), all models took the sampling design of the study into account by specifying stratum–specific baseline hazard functions. These design-based analyses allow us to draw conclusions that are valid for the general population. In the Cox regression models, follow-up time was counted from the date of the first examination until the date that the renal outcome was reached or the date of the last examination. The multivariable-adjusted model included baseline age, sex, type II diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, current smoking, use of lipid-lowering drugs, use of BP-lowering drugs, body mass index, systolic BP, day of blood sampling, total HDL cholesterol ratio, triglycerides, baseline eGFR, and baseline albuminuria as potential confounders. To adjust for day of blood sampling, the time variable t (day) was transformed as sine [(2π/365)×t] and cosine [(2π/365)×t], which were then fitted as two variables in multivariable-adjusted models (19). As an alternative approach to account for seasonal variation, we performed additional analyses using month-specific quartiles of 25(OH)D (20). The methods of the other sensitivity analyses performed are presented in Supplemental Material.

We explored potential interaction between sodium excretion and 25(OH)D levels for increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR. This was evaluated for sodium excretion and 25(OH)D as continuous variables, categories of sodium (high versus low) and 25(OH)D (high versus low), and quartiles or clinical categories (i.e., <12, 12–15, 15–20, 20–40, and >40 ng/ml) of 25(OH)D. Interactions were assessed in a crude model and multivariable-adjusted models identical to the Cox regression models outlined above except for baseline albuminuria, because we have previously shown that sodium intake is cross-sectionally related to albuminuria and longitudinally associated with albuminuria increase in the PREVEND Study (9,21).

Baseline continuous data are reported as means±SDs for normal distributed data or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for skewed data. Categorical data are presented as percentiles. A P value <0.05 (two tailed) was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria), GraphPad Prism, version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and Stata Statistical Software: Release 11 (College Station, TX).

Results

Participants

At baseline, mean age was 48±12 years old, and 47% were men. Mean 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D levels were 23.2±9.3 ng/ml and 60.6±19.6 pg/ml, respectively. Mean urinary sodium excretion was 141±50 mmol/24 h, corresponding to 3.2 g sodium (8.1 g salt) daily. Overall, 20.7% (n=1045) had 25(OH)D<15 ng/ml, and 40.0% (n=2020) had 25(OH)D<20 ng/ml. Baseline characteristics of the study population according to urinary sodium excretion and 25(OH)D groups are shown in Table 1. Significant differences between the four groups were observed for age and sex, season of sampling, ethnicity, body mass index, BP, serum glucose, lipids, serum albumin, eGFR, and urinary excretion of calcium, potassium, and albumin. The subgroup of patients excluded because of missing follow-up showed small but significant differences regarding baseline 25(OH)D levels, sodium excretion, and UAE compared with participants included in the cohort (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to urinary sodium excretion and 25-hydroxyvitamin D groups

| Characteristics | Total (n=5051) | Low Na+ and Low 25(OH)D (n=1726) | Low Na+ and High 25(OH)D (n=1640) | High Na+ and Low 25(OH)D (n=803) | High Na+ and High 25(OH)D (n=882) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary sodium excretion, mmol/24 h | <156.8 | <156.8 | ≥156.8 | ≥156.8 | — | ||

| Plasma 25(OH)D, ng/ml | <22.6 | ≥22.6 | <22.6 | ≥22.6 | |||

| Men, n (%) | 2391 (47) | 687 (40) | 589 (36) | 528 (66) | 587 (67) | <0.001 | |

| Age, yr | 48.4±11.7 | 49.3±12.4 | 48.6±11.5 | 46.8±11.1 | 47.6±10.9 | <0.001 | |

| Season, n (%) | — | <0.001 | |||||

| Summer (June–August) | 1069 (21) | 216 (13) | 476 (29) | 95 (12) | 282 (32) | — | |

| Autumn (September–November) | 1555 (31) | 442 (26) | 596 (36) | 179 (22) | 338 (38) | — | |

| Winter (December–February) | 1039 (21) | 481 (28) | 214 (13) | 247 (31) | 97 (11) | — | |

| Spring (March–May) | 1388 (28) | 587 (34) | 354 (22) | 282 (35) | 165 (19) | — | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | — | — | — | — | — | <0.001 | |

| White | 4810 (96) | 1588 (93) | 1615 (99) | 735 (93) | 872 (99) | — | |

| Black | 45 (1) | 28 (2) | 1 (0.1) | 15 (2) | 1 (0.1) | — | |

| Asian | 100 (2) | 61 (3.6) | 9 (1) | 28 (4) | 2 (0.2) | — | |

| Other | 60 (1) | 31 (2) | 7 (0.4) | 17 (2) | 5 (1) | — | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.7±3.9 | 25.4±4.0 | 24.9±3.4 | 27.1±4.6 | 26.5±3.6 | <0.001 | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | — | — | — | — | — | <0.001 | |

| Never | 1597 (32) | 553 (32) | 507 (31) | 266 (33) | 271 (31) | — | |

| Quit >1 yr | 1622 (32) | 501 (29) | 545 (33) | 239 (30) | 337 (38) | — | |

| Quit <1 yr | 197 (4) | 64 (4) | 69 (4) | 28 (4) | 36 (4) | — | |

| Current | 1621 (32) | 599 (35) | 517 (32) | 267 (33) | 238 (27) | — | |

| Type II diabetes, n (%) | 95 (2) | 33 (2) | 27 (2) | 20 (3) | 15 (2) | 0.52 | |

| History of CVD, n (%) | 168 (3) | 72 (4) | 52 (3) | 22 (3) | 22 (3) | 0.08 | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 125.8±17.9 | 126.0±19.3 | 123.5±17.7 | 128.4±16.6 | 127.3±16.2 | <0.001 | |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 72.8±9.1 | 72.5±9.3 | 72.0±9.0 | 74.1±8.9 | 73.8±8.7 | <0.001 | |

| BP-lowering drugs, n (%) | 583 (12) | 225 (13) | 179 (11) | 93 (12) | 86 (10) | 0.07 | |

| ACEi or ARB, n (%) | 160 (4) | 51 (4) | 45 (3) | 36 (6) | 28 (4) | 0.07 | |

| Lipid-lowering drugs, n (%) | 254 (5) | 85 (5) | 90 (6) | 40 (5) | 39 (4) | 0.70 | |

| Serum glucose, mg/dl | 82.9 [77.5–90.1] | 82.9 [77.5–90.1] | 82.9 [75.7–88.3] | 84.7 [79.3–91.9] | 84.7 [79.3–93.7] | <0.001 | |

| Serum total cholesterol, mg/dl | 215±43 | 214±43 | 215±43 | 217±41 | 217±42 | 0.20 | |

| Serum HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 52.1±15.4 | 52.6±15.5 | 54.6±15.4 | 48.1±13.9 | 50.3±15.3 | <0.001 | |

| Serum triglycerides, mg/dl | 98.2 [71.7–141.6] | 93.8 [69.0–136.3] | 94.7 [69.9–132.7] | 108.8 [77.9–161.1] | 107.1 [78.8–149.6] | <0.001 | |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 1.08 [0.49–2.55] | 1.08 [0.48–2.59] | 1.08 [0.49–2.45] | 1.11 [0.48–2.77] | 1.07 [0.54–2.37] | 0.88 | |

| Plasma phosphate, mg/dl | 3.11±0.49 | 3.12±0.49 | 3.10±0.49 | 3.14±0.50 | 3.10±0.50 | 0.35 | |

| Plasma calcium, mg/dl | 9.11±0.37 | 9.11±0.36 | 9.12±0.37 | 9.10±0.35 | 9.13±0.39 | 0.56 | |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 4.11±0.80 | 4.05±0.85 | 4.07±0.78 | 4.15±0.80 | 4.31±0.72 | <0.01 | |

| Plasma 1,25(OH)2D, pg/ml | 60.6±19.6 | 52.7±15.8 | 68.6±19.5 | 52.1±15.9 | 68.8±20.4 | <0.001 | |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 97.3±14.6 | 96.9±15.2 | 95.6±14.5 | 100.2±13.8 | 98.3±14.0 | <0.001 | |

| Urine potassium, mmol/24 h | 71.8±21.0 | 65.4±19.2 | 68.0±19.0 | 81.3±21.2 | 82.8±20.5 | <0.001 | |

| Urine calcium, mmol/24 h | 4.0±2.0 | 3.4±1.6 | 3.7±1.6 | 4.8±2.2 | 5.1±2.2 | <0.001 | |

| Urine albumin, mmol/24 h | 8.1 [5.9–12.1] | 8.0 [5.7–11.8] | 7.4 [5.6–11.1] | 9.3 [6.8–14.2] | 8.9 [6.5–12.7] | <0.001 | |

P values for differences between groups were assessed with ANOVA for normally distributed continuous data, the Kruskal–Wallis test for skewed distributed data, and the chi-squared test for nominal data. Baseline continuous data are reported as mean±SD for normally distributed data or median [interquartile range] for skewed data. The units presented in brackets are the interquartile ranges. 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ACEi, angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

Vitamin D and the Risk of Increased Albuminuria or Reduced eGFR

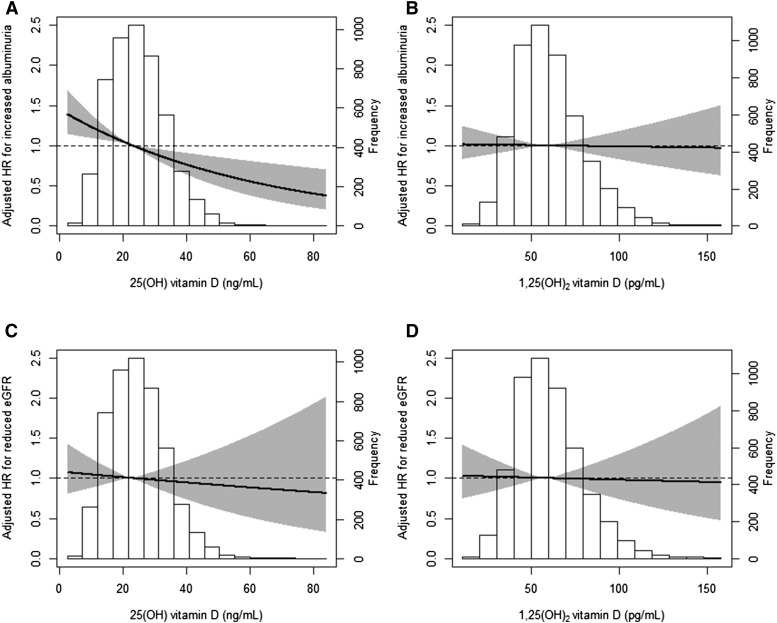

During a median follow-up period of 10.4 (IQR, 6.2–11.4) years, a total of 641 (13%) participants developed increased albuminuria (>30 mg/24 h), and 268 (5%) participants developed reduced eGFR (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). The subgroup of participants who developed increased albuminuria (>30 mg/24 h) had a median baseline albuminuria of 15.6 mg/24 h (IQR, 10.1–22.1). The median absolute change from baseline to the visit at which the outcome was reached was +27.8 mg/24 h (IQR, +19.6–+43.7). Plasma 25(OH)D was inversely associated with the risk of increased albuminuria (hazard ratio [HR] per SD higher, 0.86; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.80 to 0.94; P<0.001). This inverse association was independent of potential confounders (adjusted HR per SD higher, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.94; P=0.001) (Figure 1, Table 2). When using month-specific quartiles, results were similar (adjusted HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85 to 0.98; P<0.01).

Figure 1.

The relative risk of developing increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR according to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D] levels in the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease (PREVEND) Study. Risk of developing increased albuminuria (A and B) or reduced eGFR (C and D) according to 25(OH)D (A and C) or 1,25(OH)2D (B and D). The lines in the graphs represent the risk for developing either renal outcome compared with average 25(OH)D or 1.25(OH)2D level, respectively. The gray area represents the 95% confidence interval of the hazard ratio (HR). The HRs of the multivariable-adjusted model are shown. Data of one participant with an extreme value of 1,25(OH)2D (260 pg/ml) are not shown.

Table 2.

Associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels with risk of developing reduced eGFR or increased albuminuria in the PREVEND Study

| Renal Outcome | Univariable HR (95% CI) | No. of Patients | P Value | Multivariable HR (95% CI) | No. of Patients | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25(OH)D | ||||||

| Reduced eGFR | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.12) | 268 | 0.85 | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.10) | 260 | 0.59 |

| Increased albuminuria | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.94) | 641 | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.94) | 628 | 0.001 |

| 1,25(OH)D | ||||||

| Reduced eGFR | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.02) | 268 | 0.11 | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) | 260 | 0.86 |

| Increased albuminuria | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.09) | 641 | 0.91 | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.08) | 628 | 0.79 |

Data are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) per SD higher in 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D] concentrations plus 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Reduced eGFR is defined as an eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and increased albuminuria is defined as urinary albumin excretion >30 mg/24 h. Multivariable model includes adjustment for age, sex, presence of type II diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, current smoking, use of lipid-lowering drugs, use of BP-lowering drugs, body mass index, systolic BP, day of blood sampling, cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio, triglyceride level, baseline urinary albumin excretion, and eGFR. PREVEND, Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease.

The subgroup of participants who developed reduced eGFR had a mean baseline eGFR of 74.3±10.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2. The median absolute change from baseline to the visit at which the outcome was reached was −17.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (IQR, −26.0 to −10.4). Plasma 25(OH)D was not associated with reduced eGFR (HR per SD higher, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.87 to 1.12; P=0.85). Plasma 1,25(OH)2D was significantly associated with neither reduced eGFR nor increased albuminuria (Figure 1, Table 2). Results were similar when the eGFR end point (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) was defined according to the creatinine–based CKD-EPI formula (Supplemental Table 2). Other independent determinants of increased albuminuria and reduced eGFR are presented in Supplemental Table 3.

Sodium Intake, Vitamin D Status, and Increased Albuminuria

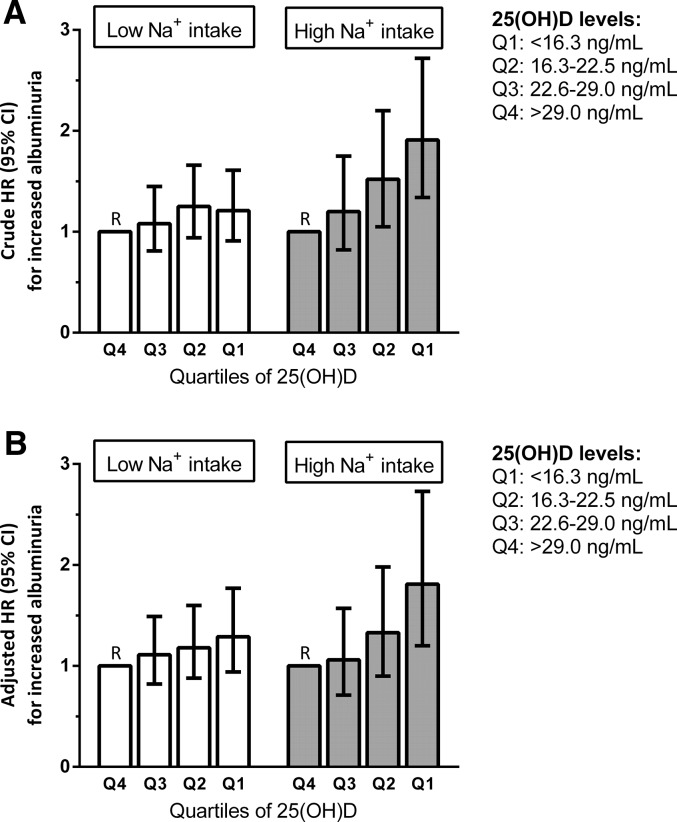

The association between 25(OH)D levels and the development of increased albuminuria was modified by baseline sodium intake (P interaction=0.03) and persisted in multivariable-adjusted analysis (P interaction=0.01). Participants with high sodium intake and low 25(OH)D levels had a higher risk of developing increased albuminuria than participants with low sodium intake and high 25(OH)D levels (Table 3). Excluding participants using angiotensin–converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy (3%) did not materially change the results (P interaction=0.03). In participants with high sodium intake, the risk of developing increased albuminuria was inversely associated with quartiles of 25(OH)D (lowest versus highest quartile: adjusted HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.73; P<0.01), whereas this effect was nonsignificant in participants with low sodium intake (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.77; P=0.12; P interaction=0.04) (Figure 2). Using clinical cutoffs for 25(OH)D levels yielded highly similar results (P interaction=0.04).

Table 3.

Associations of categories on the basis of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and urinary sodium excretion with increased albuminuria events in the PREVEND Study

| Na+/25(OH)D Category | Participants | Events | Crude Modela HR (95% CI) | Multivariable Modelb HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Na+ and high 25(OH)D | 1640 | 176 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Low Na+ and low 25(OH)D | 1726 | 216 | 1.18 (0.97 to 1.44) | 1.13 (0.92 to 1.40) |

| High Na+ and high 25(OH)D | 882 | 106 | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.33) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) |

| High Na+ and low 25(OH)D | 803 | 143 | 1.62 (1.30 to 2.02) | 1.42 (1.11 to 1.82) |

Data are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) per SD higher in 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations plus 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Increased albuminuria is defined as urinary albumin excretion >30 mg/24 h. Multivariable model includes adjustment for age, sex, presence of type II diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, current smoking, use of lipid-lowering drugs, use of BP-lowering drugs, body mass index, systolic BP, day of blood sampling, cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio, triglyceride level, and eGFR. PREVEND, Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease.

P interaction urinary sodium excretion × 25(OH)D categories =0.07 (crude model).

P interaction urinary sodium excretion × 25(OH)D categories =0.04 (multivariable model).

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] quartiles with increased albuminuria events stratified by urinary sodium excretion. Increased albuminuria is defined as urinary albumin excretion (UAE) >30 mg/24 h. (A) Crude and (B) multivariable models are shown. The model in B includes adjustment for age, sex, presence of type II diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, current smoking, use of lipid-lowering drugs, use of BP-lowering drugs, body mass index, systolic BP, day of blood sampling, cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio, triglyceride level, and eGFR. Model A: P interaction low/high urinary sodium excretion × 25(OH)D quartiles =0.04 (crude model). Model B: P interaction low/high urinary sodium excretion × 25(OH)D quartiles =0.02 (multivariable model).

We found no interaction by sodium intake for the association between 25(OH)D and reduced eGFR (P interaction =0.27).

Sensitivity Analyses

First, after exclusion of nonwhite participants, plasma 25(OH)D was inversely associated with increased albuminuria (adjusted HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79 to 0.97; P<0.01; 594 events) but not with reduced eGFR (adjusted HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.10; P=0.50; 253 events). The interaction between sodium intake and 25(OH)D on increased albuminuria did not materially change (P interaction =0.02). Second, after excluding 24-hour urine samples with possible over- or under-collection, 25(OH)D was inversely associated with increased albuminuria (adjusted HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79 to 0.96; P<0.01 589 events) but not with reduced eGFR. Additional adjustment for urine volume and creatinine excretion did not materially change the results (adjusted HR for albuminuria>30 mg/24 h, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.98; P=0.02). Interaction by urinary sodium excretion persisted for the association between 25(OH)D and the risk of increased albuminuria (P interaction =0.02). Third, we redefined increased albuminuria as UAE>40 mg/24 h (instead of >30 mg/24 h). Plasma 25(OH)D remained inversely associated with increased albuminuria (adjusted HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.89; P<0.001; 428 events). The interaction of 25(OH)D and developing increased albuminuria remained (P interaction =0.002). Fourth, when we redefined reduced eGFR as <54 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (instead of <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), 25(OH)D was not associated with reduced eGFR (adjusted HR per SD higher, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.26; P=0.70; 125 events). Fifth, when we reanalyzed the association between 25(OH)D and outcomes in participants followed up until the last time point, 25(OH)D was associated with a lower risk of increased albuminuria (odds ratio per SD higher, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.98; P=0.03) but not of reduced eGFR (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.88 to 1.23; P=0.68).

In the above sensitivity analyses, plasma 1,25(OH)2D was consistently not associated with the risk of developing increased albuminuria or reduced eGFR.

Discussion

In this prospective, observational, general population–based cohort study, a low plasma 25(OH)D level was associated with a higher risk of developing increased albuminuria (UAE>30 mg/24 h). Moreover, we found effect modification by sodium intake, with a more prominent association between low 25(OH)D and increased albuminuria in individuals with high sodium intake. Plasma 25(OH)D was not associated with reduced eGFR, and plasma 1,25(OH)2D was not associated with either outcome.

The inverse association between 25(OH)D and increased albuminuria is in line with a previous cross–sectional study (4) and a prospective general population–based study showing an association between 25(OH)D deficiency and 5-year incidence of increased albuminuria (6). We extend these observations by showing an association between low 25(OH)D and incident increased albuminuria during 10 years of follow-up. Several mechanisms could underlie the relationship between low 25(OH)D levels and increased albuminuria, including interaction with the RAAS. The VDR directly modulates prorenin gene expression by binding to its promoter region (22). In line, 1α-hydroxylase– and VDR-knockout mice display elevated renin expression and a strongly activated RAAS (23–25), whereas treatment with vitamin D analogs decreases renin expression (26). Thus, low vitamin D levels through excessive RAAS activation, resulting in high levels of angiotensin II (Ang II), can induce systemic hypertension and stimulate renal inflammation and fibrosis (27,28). Furthermore, effects of vitamin D on Wnt/β-catenin signaling (29), TGF-β (30), or suppression of NF-κB activity in macrophages (31,32) could mediate the effect of vitamin D on albuminuria.

Interestingly, we observed that the association between 25(OH)D and increased albuminuria was modified by sodium intake. We found that individuals with high sodium intake (>3.6 g sodium/24 h) who also have low 25(OH)D levels are at particular risk to develop increased albuminuria. In our population, only 12% reached the sodium intake recommended by the World Health Organization (<2.0 g) (33). The interaction of vitamin D and increased albuminuria by sodium intake could, at least partly, be mediated by the intrarenal RAAS. Preclinical studies have shown that high sodium intake increases several components of the intrarenal RAAS, including angiotensinogen (12), ACE activity (34), and Ang II (35). Accordingly, in humans, high sodium intake increased the peripheral vascular conversion of Ang I to Ang II, indicating an increase in tissue ACE activity (36). Increased renal ACE activity caused by high sodium intake combined with increased renin production caused by low vitamin D (24,37) may concertedly promote progression of albuminuria. Proinflammatory and profibrotic pathways could also underlie the interaction, because both vitamin D deficiency (25,37–39) and high sodium intake (11,40,41) have been linked to increased renal inflammation and fibrosis.

We could not show an association between 25(OH)D levels and reduced eGFR. This is in line with previous studies (6,42), although others did report an association with renal function loss (43). The relatively small decrease in eGFR during follow-up (−17.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 [IQR, −26.0 to −10.4]) may explain this negative result; studies with longer follow-up may be needed to further explore this association.

Plasma 1,25(OH)2D was not associated with increased albuminuria or reduced renal function. We hypothesize that the discordant associations of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D with increased albuminuria may be explained by autocrine/paracrine activation of 25(OH)D. This is supported by the fact that 1α-hydroxylase is expressed by various cell types other than tubular epithelial cells, including podocytes, with subsequent local activation of VDRs (44–46) and circulating levels of 25(OH)D exceeding 1,25(OH)2D by approximately 400-fold in our study.

Potential limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, our findings are observational, and therefore, despite extensive adjustment for potential confounders, residual confounding may be present. Second, vitamin D and urinary sodium excretion were measured at a single time point only; therefore, we could not take changes over time into account. Third, the end point reduced eGFR was defined using a single measurement rather than two values at least 90 days apart, which is recommended by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Although 24-hour urinary sodium excretion is considered the method of choice to assess sodium intake (33), the day to day variability of sodium excretion could not be accounted for, because we assessed baseline collections only. However, this variability is more likely to weaken rather than enhance the effect. Furthermore, participants excluded because of missing follow-up showed small but significant differences from participants included in the cohort, which could have introduced selection bias. The Cox regression models were discrete-time analyses, limiting the collection of outcomes to visits instead of continuous registration. Fourth, this cohort consisted almost entirely of whites, which limits the generalizability of our results. However, major strengths of our study are the large sample size, the serial screenings for CKD during follow-up using robust methods (creatinine/cystatin C–based eGFR and two consecutive 24-hour UAE measurements at each screening), and the measurement of vitamin D levels using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry.

In conclusion, we found that sodium intake modifies the association between plasma 25(OH)D level and the risk to develop increased albuminuria. Participants with both high sodium intake and a low 25(OH)D level have an elevated risk to develop increased albuminuria.

Disclosures

H.J.L.-H. is a consultant for and received honoraria from Abbvie, Astellas, Janssen, Reata, Vitae, and ZS-Pharma; all honoraria are paid to his institution. D.d.Z. is a consultant for and received honoraria from Abbvie, Astellas, Chemocentryx, Eli Lilly, Fresenius, and Janssen; all honoraria are paid to his institution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease Study has been made possible by grants from the Dutch Kidney Foundation. This work was supported by research grants from the Top Institute Food and Nutrition and Abbvie and Dutch Kidney Foundation NIer-Gerichte Research: van Arterie naar Mens (NIGRAM [Kidney-Centered Research: from Artery to Man]) Consortium Grant CP10.11. H.J.L.-H. is supported by a Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research Veni Grant. M.H.d.B. is supported by Dutch Kidney Foundation Grant KJPB.08.07 and a Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research Veni Grant.

This research was presented in part at the ISN World Congress of Nephrology 2015 held March 13–17, 2015 in Cape Town, South Africa.

The supporting agencies had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.03830415/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : 2014 Annual Data Report: An Overview of the Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl 113: S1–S130, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL: Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: Results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int 71: 31–38, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer IH, Ioannou GN, Kestenbaum B, Brunzell JD, Weiss NS: 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and albuminuria in the third national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES III). Am J Kidney Dis 50: 69–77, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravani P, Malberti F, Tripepi G, Pecchini P, Cutrupi S, Pizzini P, Mallamaci F, Zoccali C: Vitamin D levels and patient outcome in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 75: 88–95, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damasiewicz MJ, Magliano DJ, Daly RM, Gagnon C, Lu ZX, Sikaris KA, Ebeling PR, Chadban SJ, Atkins RC, Kerr PG, Shaw JE, Polkinghorne KR: Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency and the 5-year incidence of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 58–66, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Borst MH, Vervloet MG, ter Wee PM, Navis G: Cross talk between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and vitamin D-FGF-23-klotho in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1603–1609, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weir MR, Dengel DR, Behrens MT, Goldberg AP: Salt-induced increases in systolic blood pressure affect renal hemodynamics and proteinuria. Hypertension 25: 1339–1344, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhave JC, Hillege HL, Burgerhof JG, Janssen WM, Gansevoort RT, Navis GJ, de Zeeuw D, de Jong PE, PREVEND Study Group : Sodium intake affects urinary albumin excretion especially in overweight subjects. J Intern Med 256: 324–330, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krikken JA, Lely AT, Bakker SJ, Navis G: The effect of a shift in sodium intake on renal hemodynamics is determined by body mass index in healthy young men. Kidney Int 71: 260–265, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu HC, Burrell LM, Black MJ, Wu LL, Dilley RJ, Cooper ME, Johnston CI: Salt induces myocardial and renal fibrosis in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Circulation 98: 2621–2628, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rebholz CM, Chen J, Zhao Q, Chen JC, Li J, Cao J, Gabriel Navar L, Lee Hamm L, Gu D, He J, GenSalt Collaborative Research Group : Urine angiotensinogen and salt-sensitivity and potassium-sensitivity of blood pressure. J Hypertens 33: 1394–1400, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Zeeuw D, Agarwal R, Amdahl M, Audhya P, Coyne D, Garimella T, Parving HH, Pritchett Y, Remuzzi G, Ritz E, Andress D: Selective vitamin D receptor activation with paricalcitol for reduction of albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes (VITAL study): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 376: 1543–1551, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Nicola L, Conte G, Russo D, Gorini A, Minutolo R: Antiproteinuric effect of add-on paricalcitol in CKD patients under maximal tolerated inhibition of renin-angiotensin system: A prospective observational study. BMC Nephrol 13: 150, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diercks GF, van Boven AJ, Hillege HL, Janssen WM, Kors JA, de Jong PE, Grobbee DE, Crijns HJ, van Gilst WH: Microalbuminuria is independently associated with ischaemic electrocardiographic abnormalities in a large non-diabetic population. The PREVEND (Prevention of REnal and Vascular ENdstage Disease) study. Eur Heart J 21: 1922–1927, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen WM, Hillege H, Pinto-Sietsma SJ, Bak AA, De Zeeuw D, de Jong PE, PREVEND Study Group. Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease : Low levels of urinary albumin excretion are associated with cardiovascular risk factors in the general population. Clin Chem Lab Med 38: 1107–1110, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS, CKD-EPI Investigators : Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367: 20–29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joosten MM, Gansevoort RT, Mukamal KJ, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Geleijnse JM, Feskens EJ, Navis G, Bakker SJ, PREVEND Study Group : Sodium excretion and risk of developing coronary heart disease. Circulation 129: 1121–1128, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachs MC, Shoben A, Levin GP, Robinson-Cohen C, Hoofnagle AN, Swords-Jenny N, Ix JH, Budoff M, Lutsey PL, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum B, de Boer IH: Estimating mean annual 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations from single measurements: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr 97: 1243–1251, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Jacobs EJ, McCullough ML, Rodriguez C, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Flanders WD: Comparing methods for accounting for seasonal variability in a biomarker when only a single sample is available: Insights from simulations based on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d. Am J Epidemiol 170: 88–94, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forman JP, Scheven L, de Jong PE, Bakker SJ, Curhan GC, Gansevoort RT: Association between sodium intake and change in uric acid, urine albumin excretion, and the risk of developing hypertension. Circulation 125: 3108–3116, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan W, Pan W, Kong J, Zheng W, Szeto FL, Wong KE, Cohen R, Klopot A, Zhang Z, Li YC: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses renin gene transcription by blocking the activity of the cyclic AMP response element in the renin gene promoter. J Biol Chem 282: 29821–29830, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li YC, Kong J, Wei M, Chen ZF, Liu SQ, Cao LP: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 110: 229–238, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou C, Lu F, Cao K, Xu D, Goltzman D, Miao D: Calcium-independent and 1,25(OH)2D3-dependent regulation of the renin-angiotensin system in 1alpha-hydroxylase knockout mice. Kidney Int 74: 170–179, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Kong J, Deb DK, Chang A, Li YC: Vitamin D receptor attenuates renal fibrosis by suppressing the renin-angiotensin system. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 966–973, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiao G, Kong J, Uskokovic M, Li YC: Analogs of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) as novel inhibitors of renin biosynthesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 96: 59–66, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim S, Iwao H: Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol Rev 52: 11–34, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mezzano SA, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J: Angiotensin II and renal fibrosis. Hypertension 38: 635–638, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He W, Kang YS, Dai C, Liu Y: Blockade of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by paricalcitol ameliorates proteinuria and kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 90–103, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito I, Waku T, Aoki M, Abe R, Nagai Y, Watanabe T, Nakajima Y, Ohkido I, Yokoyama K, Miyachi H, Shimizu T, Murayama A, Kishimoto H, Nagasawa K, Yanagisawa J: A nonclassical vitamin D receptor pathway suppresses renal fibrosis. J Clin Invest 123: 4579–4594, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen-Lahav M, Shany S, Tobvin D, Chaimovitz C, Douvdevani A: Vitamin D decreases NFkappaB activity by increasing IkappaBalpha levels. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 889–897, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen-Lahav M, Douvdevani A, Chaimovitz C, Shany S: The anti-inflammatory activity of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in macrophages. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 103: 558–562, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization (WHO) : Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children, Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rook M, Lely AT, Kramer AB, van Goor H, Navis G: Individual differences in renal ACE activity in healthy rats predict susceptibility to adriamycin-induced renal damage. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 59–64, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samuel P, Ali Q, Sabuhi R, Wu Y, Hussain T: High Na intake increases renal angiotensin II levels and reduces expression of the ACE2-AT(2)R-MasR axis in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F412–F419, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boddi M, Poggesi L, Coppo M, Zarone N, Sacchi S, Tania C, Neri Serneri GG: Human vascular renin-angiotensin system and its functional changes in relation to different sodium intakes. Hypertension 31: 836–842, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Sun L, Wang Y, Ning G, Minto AW, Kong J, Quigg RJ, Li YC: Renoprotective role of the vitamin D receptor in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 73: 163–171, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonçalves JG, de Bragança AC, Canale D, Shimizu MH, Sanches TR, Moysés RM, Andrade L, Seguro AC, Volpini RA: Vitamin D deficiency aggravates chronic kidney disease progression after ischemic acute kidney injury. PLoS One 9: e107228, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zehnder D, Quinkler M, Eardley KS, Bland R, Lepenies J, Hughes SV, Raymond NT, Howie AJ, Cockwell P, Stewart PM, Hewison M: Reduction of the vitamin D hormonal system in kidney disease is associated with increased renal inflammation. Kidney Int 74: 1343–1353, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian N, Moore RS, Braddy S, Rose RA, Gu JW, Hughson MD, Manning RD, Jr.: Interactions between oxidative stress and inflammation in salt-sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3388–H3395, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slagman MC, Nguyen TQ, Waanders F, Vogt L, Hemmelder MH, Laverman GD, Goldschmeding R, Navis G: Effects of antiproteinuric intervention on elevated connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN-2) plasma and urine levels in nondiabetic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1845–1850, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guessous I, McClellan W, Kleinbaum D, Vaccarino V, Hugues H, Boulat O, Marques-Vidal P, Paccaud F, Theler JM, Gaspoz JM, Burnier M, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Bochud M: Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and kidney function decline in a swiss general adult population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1162–1169, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melamed ML, Astor B, Michos ED, Hostetter TH, Powe NR, Muntner P: 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, race, and the progression of kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2631–2639, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E: Vitamin D. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F8–F28, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsui I, Hamano T, Tomida K, Inoue K, Takabatake Y, Nagasawa Y, Kawada N, Ito T, Kawachi H, Rakugi H, Imai E, Isaka Y: Active vitamin D and its analogue, 22-oxacalcitriol, ameliorate puromycin aminonucleoside-induced nephrosis in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2354–2361, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones G: Extrarenal vitamin D activation and interactions between vitamin D₂, vitamin D₃, and vitamin D analogs. Annu Rev Nutr 33: 23–44, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.