Abstract

Background and objectives

Children with nephrotic syndrome can develop life-threatening complications, including infection and thrombosis. While AKI is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalized children, little is known about the epidemiology of AKI in children with nephrotic syndrome. The main objectives of this study were to determine the incidence, epidemiology, and hospital outcomes associated with AKI in a modern cohort of children hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Records of children with nephrotic syndrome admitted to 17 pediatric nephrology centers across North America from 2010 to 2012 were reviewed. AKI was classified using the pediatric RIFLE definition.

Results

AKI occurred in 58.6% of 336 children and 50.9% of 615 hospitalizations (27.3% in stage R, 17.2% in stage I, and 6.3% in stage F). After adjustment for race, sex, age at admission, and clinical diagnosis, infection (odds ratio, 2.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.37 to 3.65; P=0.001), nephrotoxic medication exposure (odds ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.11 to 1.64; P=0.002), days of nephrotoxic medication exposure (odds ratio, 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.05 to 1.15; P<0.001), and intensity of medication exposure (odds ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.09 to 1.65; P=0.01) remained significantly associated with AKI in children with nephrotic syndrome. Nephrotoxic medication exposure was common in this population, and each additional nephrotoxic medication received during a hospitalization was associated with 38% higher risk of AKI. AKI was associated with longer hospital stay after adjustment for race, sex, age at admission, clinical diagnosis, and infection (difference, 0.45 [log]days; 95% confidence interval, 0.36 to 0.53 [log]days; P<0.001).

Conclusions

AKI is common in children hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome and should be deemed the third major complication of nephrotic syndrome in children in addition to infection and venous thromboembolism. Risk factors for AKI include steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, infection, and nephrotoxic medication exposure. Children with AKI have longer hospital lengths of stay and increased need for intensive care unit admission.

Keywords: nephrotic syndrome, nephrotoxicity, length of stay, dialysis, acute kidney injury, child, hospitalization, humans, incidence, risk factors

Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is among the most common kidney diseases seen in childhood. Children with NS develop a variety of acute complications that can be serious and life-threatening, including infections, venous thromboembolism (VTE), and AKI. While the clinical implications of infection and VTE on children with NS are clear, the epidemiology and outcomes of AKI remain unclear. Using data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient Database (HCUP-KID), we recently reported an 8.5% incidence of AKI in children hospitalized with NS (1,2).

AKI has been identified as a risk factor for adverse outcomes among hospitalized children in both general and critical care settings (3–5). AKI is common in hospitalized adults with idiopathic NS, with up to 34% meeting any RIFLE criteria; however little is known about AKI in children with idiopathic NS (6). Children with active NS have a number of potential risk factors for the development of AKI, including intravascular volume depletion, infection, exposure to nephrotoxic medication, and renal interstitial edema leading to vascular congestion (7,8). Nephrotoxic medications are an important modifiable risk factor for the development of AKI in hospitalized children (9). This may be especially important in children with NS because nephrotoxic medications are used to treat both the underlying disease (calcineurin inhibitors [CNIs], angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACE-Is]) and its complications (antibiotics, diuretics). Infection is also frequent in this population, leading to potential exposure to nephrotoxic antibiotics, but detailed reports on the implication or burden of nephrotoxic medication exposure are lacking (10).

This multicenter retrospective study of hospitalized children with NS aimed to (1) describe the incidence of AKI through use of the pediatric version of the RIFLE AKI definition (pRIFLE), (2) evaluate known risk factors (nephrotoxic medications, infection, demographic characteristics) associated with the development of AKI, and (3) investigate the association of AKI with outcomes (length of stay [LOS]). We hypothesized that AKI would be common and would be associated with increased LOS in hospitalized children with NS.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Case Definitions

This is a multicenter retrospective study from 17 Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium centers from across North America. Local institutional review board or research ethics board approval was obtained at each participating center. All hospitalizations for children ≤18 years of age discharged from participating centers between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2012, with a discharge diagnosis of NS were reviewed. NS was defined using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) codes 581.0–3, 581.8, 581.9, 582.1, and 583.1. Hospitalizations were not recorded if children were receiving long-term RRT at admission (dialysis or kidney transplantation); were admitted for planned initiation of long-term RRT, kidney biopsy, or infusion therapy; or had known secondary NS at admission (e.g., lupus, IgA nephropathy, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and so on). Hospitalizations were excluded for analysis if the child had CKD stage ≥III at admission (11), if hospital LOS was ≤1 day or only one creatinine value was obtained, or if the child was in remission of NS at admission (defined as urine dipstick negativity or trace result for protein or protein-to-creatinine ratio <0.2 mg/mg).

Individual patient charts were reviewed for demographic and clinical data for each hospitalization. Steroid-resistant, steroid-sensitive, infrequently relapsing, frequently relapsing, and steroid-dependent NS were classified as per standard definitions (12). The method of laboratory determination of creatinine value was noted (Jaffe or isotope dilution mass spectrometry). For hospitalizations in which the Jaffe method was used, eGFR was calculated with the original Schwartz formula with a constant of 0.45 for children younger than 1 year, 0.55 for female and male patients ≤12 years, and 0.7 for male patients ≥13 years (13). For hospitalizations that used the isotope dilution mass spectrometry enzymatic method, eGFR was calculated with the updated Schwartz equation (14). Baseline creatinine value was defined as the most recent creatinine value before admission obtained within the prior 6 months. If no prior creatinine value was available, then the lowest creatinine value obtained during the hospitalization was defined as the baseline value. AKI was defined according to pRIFLE score through use of GFR criteria only (stage R, eGFR decreased by 25%; stage I, eGFR decreased by 50%; stage F, eGFR decreased by 75% or eGFR <35 ml/min per 1.73 m2) (15). Renal biopsy findings were included in the minimal-change disease (MCD) category if they had any degree of mesangial hypercellularity. Infection was diagnosed according to local criteria and included peritonitis, cellulitis/skin infection, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and bacteremia/sepsis.

Nephrotoxic medications were defined as in Moffett and Goldstein (16). Nephrotoxic medications received by each patient were recorded for each day of the hospitalization. “Medication exposure” was defined as the number of different nephrotoxic medications that children received as inpatients. “Days of medication therapy” was defined as the number of days that a child received a nephrotoxic medication and was cumulative for each medication exposure (i.e., a child who received three medications for 3 days each had 9 total days of medication therapy). “Medication exposure intensity” was defined as the number of concomitant nephrotoxic medication exposures for a child (i.e., a child who received three medications on day 1 would have a medication exposure intensity of three, whereas a child who received three medications sequentially with no overlap would have a medication exposure intensity of one) (16).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics are shown as frequency and percentage or as mean±SD as appropriate. AKI and non-AKI groups were compared using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model to account for within-patient correlation. Logistic regression with GEE was applied to test the association between AKI and its risk factors. For infection and medication exposure, the following were adjusted for in the model: age at admission, race/ethnicity, and clinical diagnosis. The association between home medication use and AKI at admission was examined in a similar fashion. LOS was transformed into a natural log scale because of skewed distribution. Multivariate linear regression with GEE was performed to test the association between LOS and AKI adjusting for age at admission, sex, race/ethnicity, clinical diagnosis, and infection. All analyses were performed using the SAS system, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values are two sided, and a P value <0.05 is considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

Results

Cohort Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We identified 370 children with 730 hospitalizations that met inclusion criteria at the participating centers. After exclusion of hospitalizations for CKD stage ≥ΙΙΙ, remission status, or LOS ≤1 day, 336 children with 632 hospitalizations remained. Seventeen hospitalizations were missing height data with which to calculate eGFR and were therefore excluded, permitting a final analysis of 336 children with 615 hospitalizations. Most children were excluded for CKD stage III or greater on admission. In keeping with this, excluded children were older (mean age, 8.5 years versus 6.2 years; P=0.003) and more likely to have FSGS (P=0.05) and steroid-resistant NS (SRNS; P=0.01). Demographic and clinical information is listed in Table 1. We found that 60.1% of children had only one hospitalization during the study period, 21.7% had two hospitalizations, 7.1% had three hospitalizations, and 11.1% had four or more hospitalizations.

Table 1.

Cohort demographic and clinical characteristics

| Category | Participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex (n=336) | |

| Male | 213 (63.4) |

| Race/ethnicity (n=284) | |

| White | 127 (44.7) |

| Hispanic | 58 (20.4) |

| Black | 65 (22.9) |

| Other | 34 (12.0) |

| Clinical pattern of NS (n=324) | |

| Steroid sensitive NS–infrequently relapsing | 99 (30.6) |

| Steroid sensitive NS—frequently relapsing or steroid-dependent | 138 (42.6) |

| Steroid-resistant NS | 83 (25.6) |

| Congenital or infantile NS | 4 (1.23) |

| Biopsy diagnosis (n=336) | |

| Minimal-change disease | 104 (31.0) |

| FSGS or FGGS | 69 (20.5) |

| Membranous, MPGN, others | 19 (5.7) |

| No biopsy | 144 (42.9) |

| Number of hospitalizations (n=336) | |

| 1 | 202 (60.1) |

| 2 | 73 (21.7) |

| 3 | 24 (7.1) |

| ≥4 | 37 (11.0) |

NS, nephrotic syndrome; FGGS, focal global glomerulosclerosis; MPGN, membranoproliferative GN.

AKI Incidence and Risk Factors

At least one episode of AKI (any pRIFLE stage) was experienced by 58.6% (n=197) of children. A sizeable number of children had multiple hospitalizations with AKI, including 7.7% (n=26) with two episodes, 4.2% (n=14) with three episodes, and 3.9% (n=13) with four or more episodes of AKI during the 3-year study period.

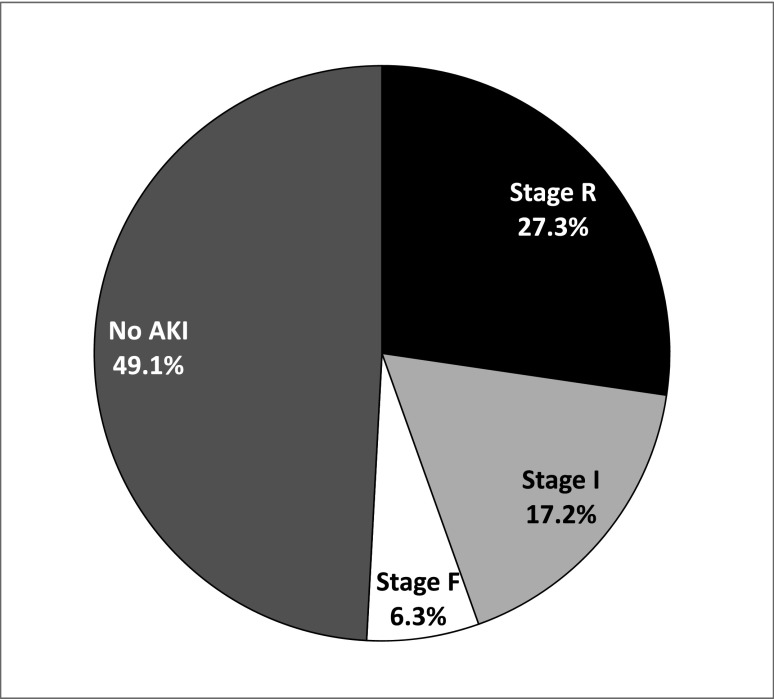

In total, 50.9% of NS hospitalizations were complicated by any pRIFLE stage of AKI (Figure 1). A total of 27.3% (n=168) of hospitalizations met the stage R criteria, 17.2% (n=106) met stage I criteria, 6.3% (n=39) met stage F criteria, and 2.0% (n=12) required RRT. A single patient death was reported during a hospitalization complicated by superior vena cava thrombosis, polymicrobial sepsis, and stage F AKI, resulting in an estimated overall mortality rate of 0.16 per 100 hospitalizations.

Figure 1.

The majority of pediatric hospitalizations for nephrotic syndrome are complicated by AKI. Almost 51% of hospitalizations for nephrotic syndrome were complicated by any pediatric RIFLE AKI definition (pRIFLE) stage of AKI. A total of 27.3% experienced stage R, 17.2% stage I, and 6.3% stage F.

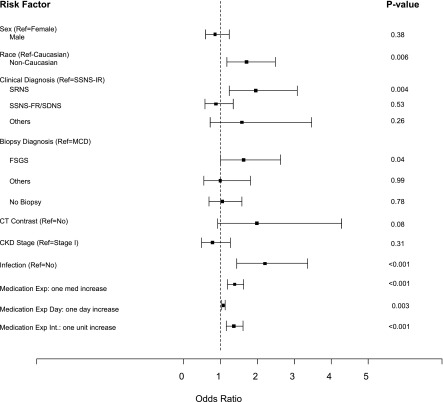

The risk for AKI did not significantly differ by sex, age at admission, biopsy diagnosis, CKD stage II at admission, serum albumin at admission, center volume, or administration of computed tomographic contrast medium (Figure 2, Table 2). Nonwhite children had a higher risk for AKI (odds ratio [OR], 1.70; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.17 to 2.48; P=0.01). Children with SRNS were more likely to develop AKI than children with steroid-sensitive NS (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.33 to 3.19). Interestingly, children with steroid-dependent/frequently relapsing NS did not have higher risk of AKI compared with children with infrequently relapsing NS (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.34; P=0.53). Infection was common in this entire cohort, with 22.6% of NS hospitalizations affected. Children with infection were twice as likely to develop AKI as children without infection (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.44 to 3.36; P≤0.001). VTE was uncommon in this cohort (1.8%).

Figure 2.

Infection, nephrotoxic medication exposure, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, and FSGS are all risk factors for AKI in children with nephrotic syndrome. Sex, use of computed tomographic (CT) contrast medium, and CKD stage at admission were not associated with risk of AKI. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS), FSGS, infection, nonwhite race, and nephrotoxic medication exposure were all significantly associated with the risk of AKI in children hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Exp, exposure; Int, intensity; MCD, minimal-change disease; Ref, reference; SDNS, steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome; SSNS-FR, steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome—frequently relapsing; SSNS-IR, steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome–infrequently relapsing.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and hospitalization data by AKI diagnosis

| Variable | AKI—Any Stage (n=313 Hospitalizations) | No AKI (n=302 Hospitalizations) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |||

| Male | 62.0 | 65.9 | 0.38 |

| Female | 38.0 | 34.1 | |

| Age at admission, % | |||

| <1 yr | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.98 |

| 1–5 yr | 45.7 | 48.3 | |

| 6–9 yr | 21.1 | 19.2 | |

| 10–18 yr | 32.0 | 31.1 | |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| White | 35.2 | 47.5 | 0.03a |

| Hispanic | 20.9 | 14.9 | |

| Black | 26.0 | 24.7 | |

| Other | 17.9 | 12.9 | |

| Clinical pattern of NS, % | |||

| SSNS—infrequently relapsing | 19.3 | 23.4 | 0.01a |

| SSNS—frequently relapsing or steroid-dependent | 36.5 | 49.8 | |

| Steroid-resistant NS | 41.5 | 24.7 | |

| Congenital or infantile NS | 2.7 | 2.1 | |

| Biopsy diagnosis, % | |||

| Minimal-change disease | 29.4 | 34.4 | 0.32 |

| FSGS or FGGS | 33.2 | 22.5 | |

| Membranous, MPGN, others | 6.4 | 8.0 | |

| No biopsy | 31.0 | 35.1 | |

| Infection, % | |||

| Yes | 29.1 | 15.9 | <0.001a |

| No | 70.9 | 84.1 | |

| CT contrast medium, % | |||

| Yes | 7.4 | 4.3 | 0.08 |

| No | 92.6 | 95.7 | |

| Baseline CKD stage, % | |||

| Stage I | 86.3 | 84.1 | 0.31 |

| Stage II | 13.7 | 15.9 | |

| Serum albumin on admission, g/dl | 1.65±0.61 | 1.71±0.67 | 0.42 |

| Medication exposure (no. of medications/hospitalization) | 0.98±1.15 | 0.65±0.82 | 0.001a |

| Medication exposure (d) | 5.04±16.69 | 2.41±4.41 | 0.01a |

| Medication exposure intensity (maximum no. of medications/d) | 0.92±1.03 | 0.65±0.81 | 0.003a |

| Center volume, % | |||

| ≤20 hospitalizations | 11.2 | 10.3 | 0.67 |

| >20 hospitalizations | 88.8 | 89.7 | |

| No. of admissions per child, % | |||

| 1–2 admissions | 49.8 | 59.9 | 0.06 |

| ≥3 admissions | 50.2 | 40.1 |

Values expressed with a ± sign are the mean±SD. Biopsy diagnosis “others” included four children with immunoglobulin M nephropathy and one each with lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency, C1q nephropathy, and congenital NS. NS, nephrotic syndrome; SSNS, steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome; FGGS, focal global glomerulosclerosis; MPGN, membranoproliferative GN; CT, computed tomographic.

P<0.05.

Children hospitalized with NS frequently received nephrotoxic medications. Almost 53% of hospitalizations were complicated by at least one nephrotoxic medication exposure during the hospital stay, while 20.9% were exposed to at least two, and 5.1% were exposed to three or more. The most commonly received nephrotoxic medications were ACE-Is (27.8% of hospitalizations), CNIs (25.5%), and nephrotoxic antibiotics (20.3%) (Table 3). Increasing number of nephrotoxic medications, days of exposure, and intensity of exposure were all associated with higher risk for AKI (Table 2).

Table 3.

Nephrotoxic medications received during hospitalization for nephrotic syndrome

| Nephrotoxic Medication | Hospitalizations (n=615), % (n) |

|---|---|

| Any nephrotoxic antibiotic | 20.3 (125) |

| Vancomycin | 8.3 (51) |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 5.5 (34) |

| Ceftazidime/cefotaxime/cefuroxime | 3.9 (24) |

| Gentamicin/tobramycin/amikacin | 2.3 (14) |

| Other (dapsone, nafcillin) | 0.3 (2) |

| Any calcineurin inhibitor | 25.5 (157) |

| Cyclosporin | 13.2 (81) |

| Tacrolimus | 12.4 (76) |

| ACE-I | 27.8 (171) |

| ARB | 6.3 (39) |

| ACE-I + ARB | 3.6 (22) |

| Antiviral (acyclovir) | 1.0 (6) |

| NSAIDs (ibuprofen/ketorolac) | 2.3 (14) |

| Other (topiramate, sirolimus) | 0.3 (2) |

ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

The final multivariate logistic regression model for AKI risk included race/ethnicity, age at admission, sex, and clinical diagnosis. After adjustment for these variables, infection (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.37 to 3.65; P=0.001), nephrotoxic medication exposure (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.64; P=0.002), days of nephrotoxic medication exposure (OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.15; P<0.001), and medication exposure intensity (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.65; P=0.01) remained significantly associated with AKI in children with NS.

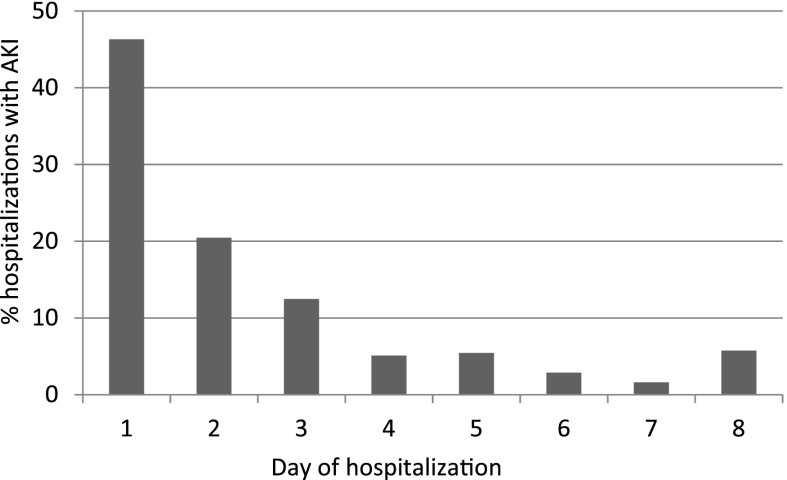

The peak creatinine value was on day 1 of admission in 46.3% of hospitalizations with AKI (Figure 3). We thus examined whether exposure to diuretics or nephrotoxic medications at home may increase the risk of AKI on admission. A total of 23.5% children were receiving loop diuretics, 24.2% were receiving CNI, and 27.6% were receiving ACE-Is or angiotensin-receptor blockers before admission. None of these home medications were associated with higher risk of AKI on admission (ACE-I/angiotensin-receptor blocker P=0.87; loop diuretic P=0.67; CNI P=0.19).

Figure 3.

The majority of children with AKI experience their peak creatinine value on day 2 of hospitalization or later. For children with AKI, the day of peak creatinine value was most often the day of hospitalization (46.3%); however, the majority of children experienced AKI on day 2 or later.

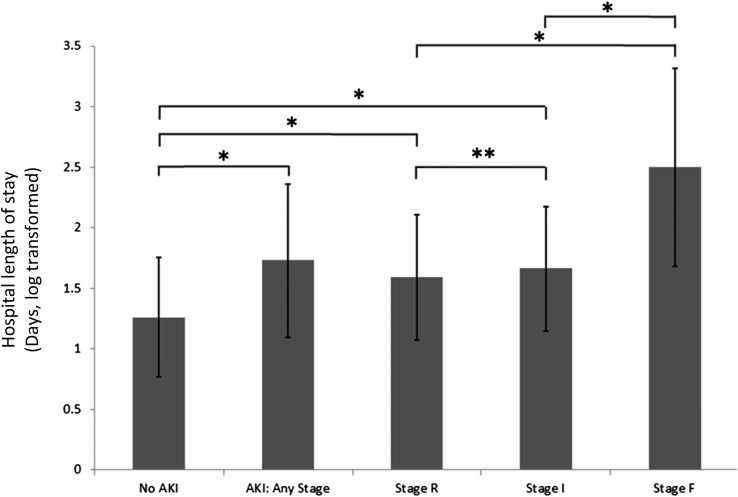

AKI was associated with a longer LOS (mean duration, 1.73±0.63 [log]days compared with 1.26±0.49 [log]days for hospitalizations without AKI; P<0.001). In addition, children with more severe stages of AKI had longer hospitalizations, ranging from 1.59±0.52 (log)days for stage R to 1.66±0.52 (log)days for stage I, and to 2.5±0.82 (log)days for stage F (Figure 4). AKI during the hospitalization was also associated with increasing need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission; 7.4% of hospitalizations with AKI requiring ICU care compared with 3.3% of hospitalizations without AKI (P=0.02).

Figure 4.

Length of stay increases in children with AKI. Length of stay (LOS) in days was natural log–transformed because of skewed distribution. Hospitalizations with any pediatric RIFLE AKI definition (pRIFLE) stage of AKI were longer than those without AKI. LOS did not differ between hospitalizations complicated by stage R and stage I AKI. Hospitalizations complicated by pRIFLE stage F AKI had significantly longer LOS than those with stage R or stage I. *P<0.001; **P=0.18.

The final multivariate linear regression model for LOS included race/ethnicity, age at admission, sex, clinical diagnosis, and infection. After adjustment for these variables, AKI remained significantly associated with LOS in children with NS (difference, 0.45 [log]days; 95% CI, 0.36 to 0.53 [log]days; P<0.001). A sensitivity analysis excluding hospitalizations with stage R AKI was performed. This analysis confirmed a significant increase in adjusted LOS in children with stages I and F compared with those with no AKI (data not shown).

Twenty-three patients with AKI underwent a kidney biopsy during their hospital stay. Causes of AKI included ATN in four patients with MCD and interstitial nephritis in one patient with MCD. In the remainder of biopsy specimens, no specific cause for AKI other than the underlying disease was identified.

Discussion

This multicenter study is the largest to date examining AKI in hospitalized children with NS. To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the incidence of AKI (50.9%) according to a modern definition (pRIFLE) of AKI as well as the risk factors associated with the development of AKI in children hospitalized with NS. We also report that children hospitalized with NS have significant nephrotoxic medication exposure, which is associated with risk for AKI.

To date, few reports have discussed on the incidence of AKI in hospitalized children with NS. The published literature has been limited to the secondary analysis of large data sets, such as the HCUP-KID data set, which rely on discharge diagnosis of AKI. In recent studies that used the HCUP-KID dataset, the rates of AKI in children hospitalized with NS were reported to be 8.5%–9.1% in 2009 (1,17). Here, we report a much higher incidence of AKI of 50.9%, which likely reflects several factors. First, mild degrees of AKI are commonly overlooked and not recorded on the discharge summary (18,19). Second, we used a standardized definition of AKI, which undoubtedly led to increased recognition of AKI. Our high reported incidence of AKI in this cohort did not represent only mild degrees of AKI, however. Moderate to severe grades of AKI were also frequent in this population. The need for RRT (2.0%) was about the same as the incidence of VTE in this cohort (1.8%; VTE is a more well known serious complication of NS) (20).

In this study, we sought to identify specific risk factors associated with the development of AKI. Frequently, AKI is attributed to prerenal azotemia from intravascular volume depletion in children with NS. To evaluate this, we measured the timing of AKI and found that 46.3% of patients had a peak creatinine value on the day of admission, which is consistent with this hypothesis. Interestingly, home loop diuretic use was not associated with risk of AKI on the day of admission, suggesting that other factors may be playing a role. A limitation of this study is that the fractional excretion of sodium and change in body weight and creatinine value over the first 24 hours of admission could not be recorded to allow us to determine whether prerenal azotemia was a possible cause of AKI on admission. While a significant number of AKI episodes were present on admission, well over 50% occurred after the first day of admission. This unexpected finding highlights the contribution of the development of intrinsic AKI during the hospitalization to the overall incidence and importance of potentially modifiable risk factors, such as nephrotoxic medications. Indeed, structural urinary biomarkers such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), that are typically upregulated in intrinsic AKI but not in functional prerenal azotemia, are also dramatically elevated in children with NS (21,22). These findings further support the notion that observed AKI is not merely due to intravascular volume depletion. The clinical utility of NGAL to differentiate between volume depletion and intrinsic AKI in NS presenting with an increased serum creatinine value remains to be explored, although it is established in other medical conditions (23,24).

Children in this cohort had a high exposure to nephrotoxic medications. Importantly, nephrotoxic medication exposure was strongly associated with the risk of AKI. The most common nephrotoxic medication exposures were ACE-Is, CNIs, and antibiotics. A limitation of this analysis is that drug levels could not be evaluated. There is some evidence for altered pharmacokinetics for nephrotoxic agents, such as gentamicin, in nephrotic children, which may increase their drug exposure (10). We were unable to determine whether increased incidence of AKI in children treated with nephrotoxic agents was due to elevated levels or simply to exposure at therapeutic levels. In the hospitalized general pediatric population, interventions based on electronic medical records are now being explored in an attempt to decrease nephrotoxic medication exposure and risk of AKI (25). These and other interventions may be required to reduce the incidence of AKI in this high-risk population of children with NS.

Hospital LOS was longer in children with more severe stages of AKI. In addition, children with AKI were more likely to require ICU care. Efforts to decrease the incidence of AKI in this population may have a substantial effect on not only patient morbidity but also health-care costs.

Children with NS are a population at risk for progressive CKD, particularly children with SRNS who have a 5-year renal survival rate of 72%–94% (26,27). Recently, there has been increasing recognition that AKI is a risk factor for development and progression of CKD in children (28,29). The contribution of individual episodes of AKI in children with NS to progressive CKD remains largely unstudied. Furthermore, it is unclear whether episodes of prerenal AKI are less hazardous in the long term for children than episodes of intrinsic AKI associated with nephrotoxic medications or other causes. An interesting finding is that 15.8% of patients had multiple episodes of AKI. To risk-stratify patients, we identified children with SRNS as having the highest risk of AKI in this cohort; thus, enhanced efforts to eliminate or minimize episodes of AKI in this subgroup of children with NS may improve long-term renal outcomes for these children. Further long-term follow-up studies should use newer biomarkers of renal injury, such as NGAL, in the NS population to more accurately determine correlations between AKI and long-term outcomes (22).

This report has several limitations. AKI was defined by the pRIFLE classification system (15). Since the publication of pRIFLE, other scoring systems for pediatric AKI have also been published and widely adopted, including the AKI Network (AKIN) and Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) classifications (30,31). In a recent comparative study, pRIFLE was the most sensitive classification system for AKI, leading to the highest percentage of hospitalizations meeting criteria for AKI compared with AKIN or KDIGO (32). Despite minor differences in the assignment of hospitalizations to AKI stage depending on which of the three classification systems is used, overall there is good correlation among them, as well as good correlations between increasing AKI stage in any classification system and increased LOS and mortality (32). Therefore, AKI rates may have been slightly lower if the AKIN or KDIGO classifications had been used in this study. Another limitation of this study is its retrospective nature, requiring future prospective studies to confirm our findings of a high incidence of intrinsic AKI in NS, and its immediate and long-term consequences.

In summary, this manuscript describes a comprehensive evaluation of AKI incidence and risk factors in a modern cohort of children hospitalized with NS in a representative cross-section of children from pediatric nephrology centers across North America. The long-term renal risk of AKI episodes in children with NS is unknown but deserves further study.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were presented at the American Society of Pediatric Nephrology annual meeting in San Diego, California, on April 26, 2015.

M.N.R. receives research support from Regulus Therapeutics and Amgen. R.A.G. is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases DK098135-01A1, DK094987 and is the recipient of a Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award. R.A.G. acknowledges that part of this work was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, grant no. 2009033. P.D. is supported by NIH P50 DK 096418 and is a coinventor on submitted patents for the use of NGAL as a biomarker of kidney injury. C.L.T. receives research support from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.06620615/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rheault MN, Wei CC, Hains DS, Wang W, Kerlin BA, Smoyer WE: Increasing frequency of acute kidney injury amongst children hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 29: 139–147, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HCUP Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID): Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 1997, 2000, 2003, 2006 Ed. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp. Accessed March 2, 2010

- 3.Sutherland SM, Ji J, Sheikhi FH, Widen E, Tian L, Alexander SR, Ling XB: AKI in hospitalized children: Epidemiology and clinical associations in a national cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1661–1669, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkandari O, Eddington KA, Hyder A, Gauvin F, Ducruet T, Gottesman R, Phan V, Zappitelli M: Acute kidney injury is an independent risk factor for pediatric intensive care unit mortality, longer length of stay and prolonged mechanical ventilation in critically ill children: A two-center retrospective cohort study. Crit Care 15: R146, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider J, Khemani R, Grushkin C, Bart R: Serum creatinine as stratified in the RIFLE score for acute kidney injury is associated with mortality and length of stay for children in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 38: 933–939, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen T, Lv Y, Lin F, Zhu J: Acute kidney injury in adult idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Ren Fail 33: 144–149, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowenstein J, Schacht RG, Baldwin DS: Renal failure in minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Am J Med 70: 227–233, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koomans HA: Pathophysiology of edema and acute renal failure in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp 30: 41–55, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein SL, Kirkendall E, Nguyen H, Schaffzin JK, Bucuvalas J, Bracke T, Seid M, Ashby M, Foertmeyer N, Brunner L, Lesko A, Barclay C, Lannon C, Muething S: Electronic health record identification of nephrotoxin exposure and associated acute kidney injury. Pediatrics 132: e756–e767, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Martin G, Bravo I, Vargas H, Arancibia A: Pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in children with nephrotic syndrome. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 24: 555–558, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogg RJ, Furth S, Lemley KV, Portman R, Schwartz GJ, Coresh J, Balk E, Lau J, Levin A, Kausz AT, Eknoyan G, Levey AS, National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative : National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease in children and adolescents: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Pediatrics 111: 1416–1421, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gipson DS, Massengill SF, Yao L, Nagaraj S, Smoyer WE, Mahan JD, Wigfall D, Miles P, Powell L, Lin JJ, Trachtman H, Greenbaum LA: Management of childhood onset nephrotic syndrome. Pediatrics 124: 747–757, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, Jr, Spitzer A: A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics 58: 259–263, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL: New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 629–637, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akcan-Arikan A, Zappitelli M, Loftis LL, Washburn KK, Jefferson LS, Goldstein SL: Modified RIFLE criteria in critically ill children with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 71: 1028–1035, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moffett BS, Goldstein SL: Acute kidney injury and increasing nephrotoxic-medication exposure in noncritically-ill children. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 856–863, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gipson DS, Messer KL, Tran CL, Herreshoff EG, Samuel JP, Massengill SF, Song P, Selewski DT: Inpatient health care utilization in the United States among children, adolescents, and young adults with nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 910–917, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmody JB, Swanson JR, Rhone ET, Charlton JR: Recognition and reporting of AKI in very low birth weight infants. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2036–2043, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaffzin JK, Dodd CN, Nguyen H, Schondelmeyer A, Campanella S, Goldstein SL: Administrative data misclassifies and fails to identify nephrotoxin-associated acute kidney injury in hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr 4: 159–166, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerlin BA, Ayoob R, Smoyer WE: Epidemiology and pathophysiology of nephrotic syndrome-associated thromboembolic disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 513–520, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer E, Elger A, Elitok S, Kettritz R, Nickolas TL, Barasch J, Luft FC, Schmidt-Ott KM: Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin distinguishes pre-renal from intrinsic renal failure and predicts outcomes. Kidney Int 80: 405–414, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett MR, Piyaphanee N, Czech K, Mitsnefes M, Devarajan P: NGAL distinguishes steroid sensitivity in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 27: 807–812, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soto K, Papoila AL, Coelho S, Bennett M, Ma Q, Rodrigues B, Fidalgo P, Frade F, Devarajan P: Plasma NGAL for the diagnosis of AKI in patients admitted from the emergency department setting. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 2053–2063, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickolas TL, Schmidt-Ott KM, Canetta P, Forster C, Singer E, Sise M, Elger A, Maarouf O, Sola-Del Valle DA, O’Rourke M, Sherman E, Lee P, Geara A, Imus P, Guddati A, Polland A, Rahman W, Elitok S, Malik N, Giglio J, El-Sayegh S, Devarajan P, Hebbar S, Saggi SJ, Hahn B, Kettritz R, Luft FC, Barasch J: Diagnostic and prognostic stratification in the emergency department using urinary biomarkers of nephron damage: a multicenter prospective cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol 59: 246–255, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkendall ES, Spires WL, Mottes TA, Schaffzin JK, Barclay C, Goldstein SL: Development and performance of electronic acute kidney injury triggers to identify pediatric patients at risk for nephrotoxic medication-associated harm. Appl Clin Inform 5: 313–333, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zagury A, Oliveira AL, Montalvão JA, Novaes RH, Sá VM, Moraes CA, Tavares MS: Steroid-resistant idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children: Long-term follow-up and risk factors for end-stage renal disease. J Bras Nefrol 35: 191–199, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamasaki Y, Yoshikawa N, Nakazato H, Sasaki S, Iijima K, Nakanishi K, Matsuyama T, Ishikura K, Ito S, Kaneko T, Honda M, for Japanese Study Group of Renal Disease in Children : Prospective 5-year follow-up of cyclosporine treatment in children with steroid-resistant nephrosis. Pediatr Nephrol 28: 765–771, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein SL, Jaber BL, Faubel S, Chawla LS, Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group of American Society of Nephrology : AKI transition of care: A potential opportunity to detect and prevent CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 476–483, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein SL, Devarajan P: Acute kidney injury in childhood: Should we be worried about progression to CKD? Pediatr Nephrol 26: 509–522, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A, Acute Kidney Injury N, Acute Kidney Injury Network : Acute Kidney Injury Network: Report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 11: R31, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kellum JA, Lameire N, KDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group : Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: A KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care 17: 204, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutherland SM, Byrnes JJ, Kothari M, Longhurst CA, Dutta S, Garcia P, Goldstein SL: AKI in hospitalized children: Comparing the pRIFLE, AKIN, and KDIGO definitions. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 554–561, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.