Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes two types of external genital lesions (EGLs) in men: genital warts (condyloma) and penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN).

Objective

The purpose of this study was to describe genital HPV progression to a histopathologically confirmed HPV-related EGL.

Design, Setting and Participants

A prospective analysis nested within the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study was conducted among 3033 men. At each visit, visually distinct EGLs were biopsied, subjected to pathological evaluation, and categorized by pathological diagnoses. Genital swabs and biopsies were used to identify HPV types using the Linear Array genotyping method for swabs and INNO-LiPA for biopsies.

Outcome Measurements

EGL incidence was determined among 1788 HPV-positive men, and cumulative incidence rates at 6, 12, and 24 months were estimated. The proportion of HPV infections that progressed to EGL was also calculated, along with median time to EGL development.

Results and Limitations

Among 1788 HPV-positive men, 92 developed an incident EGL during follow-up (9 PeIN and 86 condyloma). During the first 12 months of follow-up, 16% of men with a genital HPV6 infection developed a HPV6-positive condyloma, and 22% of genital HPV11 infections progressed to an HPV11-positive condyloma. During the first 12-months of follow-up, 0.5% of men with a genital HPV16 infection developed an HPV16-positive PeIN. Although we expected PeIN to be a rare event, the sample size for PeIN (n=10) limited the types of analyses that could be performed.

Conclusions

Most EGLs develop following infection with HPV 6, 11, or 16, all of which could be prevented with the 4-valent HPV vaccine.

Patient Summary

In this study, we looked at genital HPV infections that can cause lesions in men. The HPV that we detected within the lesions could be prevented through a vaccine.

Keywords: HIM Study, external genital lesion (EGL), PeIN, Condyloma, human papillomavirus (HPV)

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes penile, oropharyngeal, and anal cancer in men (1). HPV causes two types of external genital lesions (EGLs): condylomata acuminata, commonly referred to as condyloma or genital warts, and penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN), believed to be a precursor to penile cancer. HPV types 6 and 11 are the most frequently detected types in condyloma (96–100%) (2, 3). Factors associated with the incidence of condyloma in men include younger age (<30 years), high lifetime number of male or female sexual partners (4, 5). An estimated $200 million is spent annually in the US for condyloma treatment, which is often ineffective (5, 6). Thus, identifying the probability of which commonly occurring genital HPV infections progress to condyloma is of major clinical importance.

Although rare, penile cancer is associated with a high morbidity and mortality. There is large geographical variation in the incidence of penile cancer, with low rates observed in the US (~1/100,000) and highest rates in Brazil (~5/100,000) (7, 8). Penile cancer most commonly affects males 50–70 years old (8). Few studies have examined PeIN HPV type distribution (9–14), with most testing only for HPV 16 and 18. Factors associated with penile cancer include lack of circumcision and some sexual behaviors (15, 16). However, no studies to date have estimated PeIN prevalence or incidence or examined progression of genital HPV infection to PeIN (17).

We are uniquely poised to address these fundamental questions within the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. The purpose of this study was to describe genital HPV progression to a histopathologically confirmed EGL, specifically condyloma and PeIN, among otherwise healthy adult men. We estimated the percentage of genital HPV infections that progressed to an EGL, as well as the cumulative incidence rates for EGL development.

Methods

Study design and population

The HIM Study participants are men aged 18–70 years living in Tampa, Florida (U.S.), Cuernavaca (Mexico), and Sao Paulo (Brazil) enrolled between July 2005 and June 2009. A full description of study procedures has been published elsewhere (18, 19). Every six months, participants undergo interview, a physical exam, and laboratory analysis. The biopsy and pathology protocol was implemented in February 2009. Men who had two or more study visits after implementation of the protocol were included in this study (n=3033).

All participants provided written informed consent. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of South Florida (Tampa, FL, US), the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (Sao Paulo, Brazil), and the Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica (Cuernavaca, Mexico).

Genital skin specimen collection for HPV detection

Participants underwent a clinical examination at each visit. Using prewetted Dacron swabs, genital specimens were collected from the coronal sulcus/glans penis, penile shaft, and scrotum (19). These specimens were combined into one sample per participant and archived. Specimens underwent DNA extraction (Qiagen Media Kit), PCR analysis, and HPV genotyping (Roche Linear Array) (20). If samples tested positive for β-globin or an HPV genotype, they were considered adequate and were included in the analysis. The Linear Array assay tests for 37 HPV types, classified as high-risk (HR-HPV: 16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/68) or low-risk (LR-HPV: 6/11/26/40/42/53/54/55/61/62/64/66/67/69/70/71/72/73/81/82/IS39/83/84/89) (21).

EGL specimen collection and HPV detection

A full description of study procedures has been published elsewhere (12). Briefly, at each clinic visit, men were examined under 3x light magnification by a trained clinician for the presence of EGLs. A tissue sample was obtained from each lesion by shave excision. All EGLs that appeared to be HPV-related or had an unknown etiology based on visual inspection were sent for HPV testing. EGLs were categorized as condyloma, suggestive of condyloma, PeIN, or not HPV-related, based on the previously reported criteria (12, 22). PeIN lesions were further categorized as PeINI (low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [SIL]), PeINII (high-grade SIL), PeINII/III (high-grade SIL), and PeINIII (high-grade SIL).

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue was provided for each of the shave excision specimens. DNA was extracted from these FFPE specimens using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and genotyping was performed to detect HPV DNA from cell specimens using an AutoBlot 3000H processor (MedTec Biolab) and the INNO-LiPA HPV Genotyping Extra assay (Fujirebio), which detects 28 HPV genotypes (HR-HPV: 16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/68; LR-HPV: 6/11/26/40/43/44/53/54/66/69/70/71/73/74/82).

Statistical analysis

Men with an incident or prevalent genital HPV infection and without a prevalent condyloma or PeIN lesion at the biopsy protocol baseline visit were included in the analyses. Demographic characteristics were compared among men that did and did not develop an EGL using the Monte Carlo estimation of exact Pearson chi-square tests. HPV infection was reported by genotype or grouped (any, HR-HPV, LR-HPV, and vaccine (HPV types 6/11/16/18)). The classification of any HPV type was defined as a positive test result for at least one of 25 (HPV types 43/44/74 are not detected through Linear Array assay) HPV genotypes detected by INNO-LiPA. HPV infections with single or multiple HR-HPV types were classified as HR and those with at least one LR-HPV type were classified as low risk.

Time-to-event approach was applied to assess the time from type-specific genital HPV positivity to EGL incidence harboring the same HPV type within the lesion. The analytical unit for this study is infection. HPV genital infections that did not progress to EGL were censored at the last visit. The 6-, 12-, and 24-month cumulative incidence of EGLs and median time to EGL development for individual genital HPV types was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. For grouped genital HPVs, we adjusted for within-subject correlation using the clustered Kaplan-Meier method (23) as men could have been infected with multiple HPV types within a defined group. The overall EGL incidence rate during the study period was also calculated. Multiple HPV types could be detected in a single EGL, and a man could develop multiple EGLs. The EGL pathologic diagnoses “suggestive of condyloma” and “condyloma” were grouped together in the analyses, as the former shared at least two and up to four of the pathologic characteristics found in condyloma (12).

Results

After excluding men with a prevalent HPV-related EGL, 1788 had a prevalent or incident genital HPV infection during follow-up and were included in this analysis. These 1788 men had a total of 4315 genital HPV infections during follow-up; 1849 were prevalent HPV infections, and 2466 were incident HPV infections. Among the 1788 men with an HPV infection during follow-up, 5% developed an incident EGL (86 men had condyloma and 9 men had PeIN lesions). Age was the only significant demographic characteristics between men that developed an EGL and men that did not develop an EGL with younger age (<30 years) being more likely to develop an EGL (Table 1). Overall, the incidence rate for condyloma was 2.77 per 1000 person-months (p-m) and 0.21 per 1000 p-m for PeIN. Five percent of men (86/1788) with a genital HPV infection progressed to condyloma with the same HPV type detected in the lesion, and less than 1% of men (9/1788) with a genital HPV infection progressed to a PeIN with the same HPV detected in the lesion.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics among HPV-positive men who did and did not develop an EGL during follow-up in the HIM Study

| No EGL (n=1696) N (%) |

EGL (n=92) N (%) |

P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 0.32 | ||

| United States | 498 (29.4) | 31 (33.7) | |

| Brazil | 743 (43.8) | 33 (35.9) | |

| Mexico | 455 (26.8) | 28 (30.4) | |

| Age | 0.02 | ||

| 18–30 | 662 (39.0) | 48 (52.2) | |

| 31–44 | 700 (41.3) | 34 (37.0) | |

| 45–74 | 334 (19.7) | 10 (10.9) | |

| Race | 0.56 | ||

| White | 812 (47.9) | 47 (51.1) | |

| Black | 311 (18.3) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 37 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Other | 511 (30.1) | 27 (29.3) | |

| Refused | 25 (1.5) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.62 | ||

| Hispanic | 721 (42.5) | 38 (41.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 955 (56.3) | 54 (58.7) | |

| Missing | 20 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Years of Education | 0.94 | ||

| ≤12 Years | 730 (43) | 39 (42.4) | |

| 13–15 Years | 445 (26.2) | 26 (28.3) | |

| ≥16 Years | 515 (30.4) | 27 (29.3) | |

| Refused | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Marital Status | 0.36 | ||

| Single | 674 (39.7) | 42 (45.7) | |

| Married/Cohabiting | 816 (48.1) | 36 (39.1) | |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 201 (11.9) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Refused | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Circumcised | 0.18 | ||

| Not Circumcised | 1098 (64.7) | 53 (57.6) | |

| Circumcised | 598 (35.3) | 39 (42.4) | |

| Vaginal Condom Use | 0.90 | ||

| No Sex | 255 (15.0) | 15 (16.3) | |

| Always | 246 (14.5) | 12 (13.0) | |

| Sometimes | 586 (34.6) | 34 (37.0) | |

| Never | 547 (32.3) | 27 (29.3) | |

| Missing | 62 (3.7) | 4 (4.3) | |

| Anal Condom Use | 0.48 | ||

| No Anal Sex | 1121 (66.1) | 60 (65.2) | |

| Always | 166 (9.8) | 10 (10.9) | |

| Sometimes | 141 (8.3) | 10 (10.9) | |

| Never | 233 (13.7) | 8 (8.7) | |

| Missing | 35 (2.1) | 4 (4.3) | |

| Cigarette Smoking Status | 0.53 | ||

| Current | 419 (24.7) | 28 (30.4) | |

| Former | 541 (31.9) | 27 (29.3) | |

| Never | 713 (42.0) | 37 (40.2) | |

| Missing | 23 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Alcoholic Drinks per Month | 0.39 | ||

| 0 | 362 (21.3) | 16 (17.4) | |

| 1–30 | 697 (41.1) | 45 (48.9) | |

| >30 | 569 (33.5) | 29 (31.5) | |

| Missing | 68 (4.0) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Any STI (From Survey) | 0.50 | ||

| Negative | 541 (31.9) | 33 (35.9) | |

| Positive | 1153 (68.0) | 59 (64.1) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total Number of Female Sex Partners | 0.99 | ||

| 0–1 | 164 (9.7) | 10 (10.9) | |

| 2–9 | 532 (31.4) | 27 (29.3) | |

| 10–49 | 762 (44.9) | 42 (45.7) | |

| 50+ | 193 (11.4) | 11 (12.0) | |

| Refused | 45 (2.7) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Total Number of Male Sex Partners | 1.00 | ||

| 0 | 1357 (80.0) | 75 (81.5) | |

| 1–9 | 219 (12.9) | 12 (13) | |

| 10+ | 96 (5.7) | 5 (5.4) | |

| Missing | 24 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Sexual Orientation | 0.79 | ||

| Men Sex with Women (MSW) | 1397 (82.4) | 79 (85.9) | |

| Men Sex with Men (MSM) | 74 (4.4) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Men Sex with Men and Women (MSWM) | 147 (8.7) | 7 (7.6) | |

| Missing | 78 (4.6) | 3 (3.3) |

P-values were calculated using Monte Carlo estimation of exact Pearson chi-square tests. Missing values were not included in p-value calculations

Considering HPV infection as the unit of analysis, 2.3% (98/4315) of genital HPV infections progressed to condyloma with the same HPV type detected in the lesion, with a median time from infection to condyloma of 7.6 months (Table 2). However, for HPV6, twelve times as many infections progressed to condyloma, with 25% (59/240) of infections progressing to HPV6-positive condyloma and a median time from infection to condyloma of 7.8 months. Similarly, 23% (17/73) of genital HPV11 infections progressed to an HPV11-positive condyloma, with a median time from infection to condyloma of 4.1 months (Table 2). Few HPV16 (1%, 4/374) and HPV18 genital infections (0.7%, 1/146) progressed to a condyloma.

Table 2.

Progression of genital HPVa infection to external genital lesions (EGLs)b with the same HPV type detected in the lesion among 1788 men in the HIM Study

| HPV Type | Condyloma | PeIN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of HPV infections that progressc (%) | Median Time to EGLd | Proportion of HPV infections that progressc (%) | Median Time to EGLd | |

| Any HPV | 98/4315 (2.3) | 7.6 | 10/4323 (0.2) | 12.7 |

| Vaccinee | 81/833 (9.7) | 7.1 | 9/839 (1.1) | 6.7 |

| High Risk | 15/2460 (0.6) | 7.8 | 6/2461 (0.2) | 19.0 |

| 16 | 4/374 (1.1) | 7.4 | 6/374 (1.6) | 19.0 |

| 18 | 1/146 (0.7) | 5.7 | 0/145 (0.0) | NE |

| 31 | 1/119 (0.8) | 5.7 | 0/119 (0.0) | NE |

| 33 | 0/41 (0.0) | NE | 0/41 (0.0) | NE |

| 35 | 0/87 (0.0) | NE | 0/87 (0.0) | NE |

| 39 | 1/224 (0.5) | 1.0 | 0/225 (0.0) | NE |

| 45 | 1/132 (0.8) | 23.9 | 0/132 (0.0) | NE |

| 51 | 2/378 (0.5) | 13.2 | 0/378 (0.0) | NE |

| 52 | 4/295 (1.4) | 8.5 | 0/296 (0.0) | NE |

| 56 | 1/113 (0.9) | 0.4 | 0/113 (0.0) | NE |

| 58 | 0/142 (0.0) | NE | 0/142 (0.0) | NE |

| 59 | 0/299 (0.0) | NE | 0/299 (0.0) | NE |

| 68 | 0/110 (0.0) | NE | 0/110 (0.0) | NE |

| Low Risk | 83/1855 (4.5) | 7.6 | 4/1862 (0.2) | 4.0 |

| 6 | 59/240 (24.9) | 7.8 | 2/246 (0.8) | 3.4 |

| 11 | 17/73 (23.3) | 4.1 | 1/74 (1.4) | 1.2 |

| 26 | 0/26 (0.0) | NE | 0/26 (0.0) | NE |

| 40 | 1/117 (0.9) | 6.9 | 0/117 (0.0) | NE |

| 53 | 2/349 (0.6) | 11.1 | 0/349 (0.0) | NE |

| 54 | 1/217 (0.5) | 7.8 | 0/217 (0.0) | NE |

| 66 | 3/363 (0.8) | 12.8 | 0/363 (0.0) | NE |

| 69/71 | 0/113 (0.0) | NE | 0/113 (0.0) | NE |

| 70 | 0/161 (0.0) | NE | 0/161 (0.0) | NE |

| 73 | 0/125 (0.0) | NE | 1/125 (0.8) | 30.5 |

| 82 | 0/71 (0.0) | NE | 0/71 (0.0) | NE |

Abbreviation: PeIN- penile intraepithelial neoplasia, NE-not estimable.

DNA detected using Linear Array.

Newly acquired-pathologically confirmed EGL.

The unit of analyses is the genital HPV infection (4310 genital HPV infection among 1788 men).

Follow-up time in months.

Vaccine HPV types 6/11/16/18

Less than 1% (10/4323) of genital HPV infections progressed to PeIN with the same HPV type detected in the lesion, with a median time from infection to PeIN of 12.7 months (Table 2). Two percent (6/374) of genital HPV16 infections progressed to an HPV16-positive PeIN, with a median time from infection to PeIN of 19.0 months (Table 2). No other HR-HPV genital infections progressed to PeIN during follow-up. Three LR-HPV types at the genitals (6, 11, and 73) progressed to HPV6-positive PeIN (0.8%), HPV11-positive PeIN (1.4%), and HPV73-positive PeIN (0.8%).

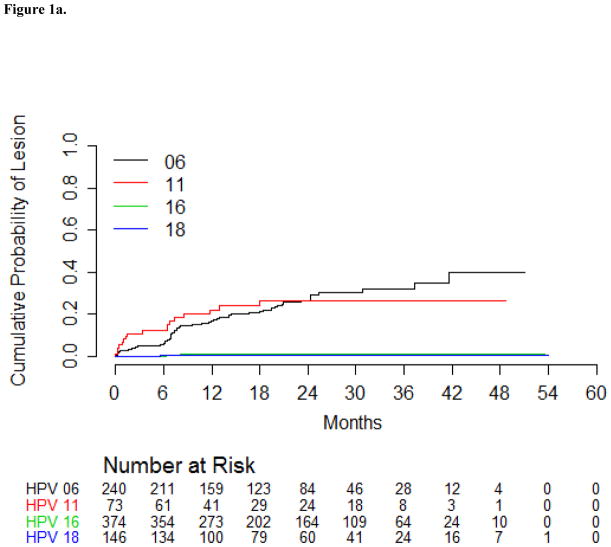

The HPV6-positive condyloma incidence rate among men with a prior HPV6 infection was 12.7 per 1000 p-m (Table 3). Similarly, the incidence of HPV11-positive condyloma among men with a prior HPV 11 infection was 13.1 per 1000 p-m (Table 3). During the first six months of follow-up, 5.9% of men with a genital HPV6 infection developed an HPV6-positive condyloma, and by 24 months of follow-up, 27% of those men developed an HPV6-positive condyloma (Table 3). A genital HPV11 infection was more likely to progress to an HPV11-positive condyloma within six months (13.1%) compared to a genital HPV6 infection (5.9%); however, the cumulative incidence of condyloma was similar for HPV 6 and 11 at 24 months (Figure 1a). Incidence rates and cumulative incidence for condyloma are presented separately for prevalent and incident genital HPV infections (Supplementary Table 1). HPV types detected within condyloma are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 3.

Incidence of condylomaa by HPV type detected in the lesion among menb with the same HPV type detected at the genitals in the HIM Study

| HPV Typede | Incidence Ratec (95% CI) | Cumulative Incidence (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-Month (95% CI) | 12-Month (95% CI) | 24-Month (95% CI) | ||

| Any | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.7 (0.4–0.9) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 2.7 (2.1–3.3) |

| Vaccinef | 4.7 (3.7–5.8) | 2.9 (1.8–4.0) | 7.3 (5.4–9.1) | 11.1 (8.7–13.6) |

| High Risk | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 0.2 (0.0–0.3) | 0.6 (0.2–0.9) | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) |

| 16 | 0.5 (0.1–1.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.9 (0.3–2.8) | 1.3 (0.5–3.6) |

| 18 | 0.3 (0.0–1.7) | 0.7 (0.1–4.9) | 0.7 (0.1–4.9) | 0.7 (0.1–4.9) |

| 31 | 0.4 (0.0–2.3) | 0.9 (0.1–6.2) | 0.9 (0.1–6.2) | 0.9 (0.1–6.2) |

| 39 | 0.2 (0.0–1.2) | 0.5 (0.1–3.2) | 0.5 (0.1–3.2) | 0.5 (0.1–3.2) |

| 45 | 0.3 (0.0–1.9) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.7 (0.2–11.6) |

| 51 | 0.2 (0.0–0.9) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.3 (0.0–2.3) | 0.8 (0.2–3.2) |

| 52 | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.2 (0.4–3.7) | 1.2 (0.4–3.7) |

| 56 | 0.4 (0.0–2.0) | 0.9 (0.1–6.1) | 0.9 (0.1–6.1) | 0.9 (0.1–6.1) |

| Low Risk | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | 1.3 (0.8–1.8) | 3.3 (2.4–4.2) | 5.3 (4.1–6.4) |

| 6 | 12.7 (9.6–16.3) | 5.9 (3.5–9.7) | 16.4 (12.1–22.1) | 26.6 (20.8–33.6) |

| 11 | 13.1 (7.7–21.0) | 12.3 (6.6–22.4) | 21.9 (13.8–33.9) | 26.7 (17.2–40.0) |

| 40 | 0.4 (0.0–2.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.0 (0.1–7.0) | 1.0 (0.1–7.0) |

| 53 | 0.3 (0.0–0.9) | 0.3 (0.0–2.0) | 0.3 (0.0–2.0) | 0.8 (0.2–3.5) |

| 54 | 0.2 (0.0–1.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.6 (0.1–4.1) | 0.6 (0.1–4.1) |

| 66 | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.3 (0.0–2.4) | 1.2 (0.4–3.8) |

Abbreviation: CI-confidence interval.

DNA detected using Linear Array.

Newly acquired, pathologically confirmed condyloma/suggestive of condyloma.

Incidence rate is cases per 1000 person-months.

Prevalent and incident genital HPV infections.

HPV types 33/35/58/59/26/68/69/71/70/73/82 did not progress to a condyloma lesion; therefore, incidence rates and cumulative incidence could not be calculated.

Vaccine HPV types 6/11/16/18

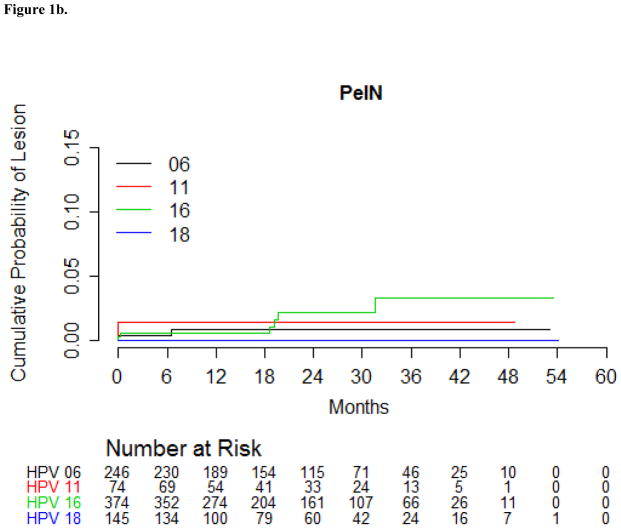

Figure 1.

Figure 1a: Cumulative incidence of condyloma with the same HPV type detected in the lesion among men in the HIM Study with a genital HPV infection using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Figure 1b: Cumulative incidence of Penile Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PeIN) with the same HPV type detected in the lesion among men in the HIM Study with a genital HPV infection using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

The HPV16-positive PeIN incidence rate among men with a prior genital HPV16 infection was 0.7 per 1000 p-m (Table 4). During the first six months of follow-up, 0.5% of men with a genital HPV16 infection developed a HPV16-positive PeIN, and by 24 months of follow-up, 2.1% of those men with a genital HPV16 infection developed PeIN (Table 4). By 24 months of follow-up, 0.9% of men with a genital HPV6 infection developed a HPV6-positive PeIN, and 1.4% of men with a genital HPV11 infection developed a HPV11-positive PeIN (Figure 1b). For the development of PeIN, all of the genital HPV infections except one were prevalent infections. The one incident genital HPV infection was an HPV16 infection that progressed to an HPV16-positive PeIN 19 months later. The HPV types detected within the ten incident PeIN lesions are presented in Table 5. The majority of PeIN lesions were HPV16-positive (60%), and of these, two (33%) were also HPV6- or HPV11-positive. Single infections with HPV11 (PeIN I) and HPV6 (PeIN III) were also observed.

Table 4.

Incidence of PeINa by HPV type detected in the lesion among menb with the same HPV type detected at the genitals in the HIM Study

| HPV Typede | Incidence Ratec (95% CI) | Cumulative Incidence (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-Month (95% CI) | 12-Month (95% CI) | 24-Month (95% CI) | ||

| Any | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.3 (0.1–0.4) |

| Vaccinef | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | 0.5 (0.0–0.9) | 0.6 (0.1–1.1) | 1.3 (0.4–2.2) |

| High Risk | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.3 (0.0–0.6) |

| 16 | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) | 2.1 (0.9–5.2) |

| Low Risk | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | 0.2 (0.0–0.4) | 0.2 (0.0–0.4) |

| 6 | 0.3 (0.0–1.3) | 0.4 (0.1–2.9) | 0.9 (0.2–3.4) | 0.9 (0.2–3.4) |

| 11 | 0.6 (0.0–3.4) | 1.4 (0.2–9.2) | 1.4 (0.2–9.2) | 1.4 (0.2–9.2) |

| 73 | 0.4 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

Abbreviation: PeIN- penile intraepithelial neoplasia, CI-confidence interval.

DNA detected using Linear Array.

Newly acquired-pathologically confirmed PeIN.

Incidence rate is cases per 1000 person-months.

Prevalent and incident genital HPV infection.

HPV types 18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/68/26/40/53/54/66/69/71/70/82 did not progress to a PeIN lesion; therefore, incidence rates and cumulative incidence could not be calculated.

Vaccine HPV types 6/11/16/18

Table 5.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN) lesions diagnosed in the HIM Study biopsy cohort

| Country | Pathology Diagnosis | Biopsy Location | HPV Detected within the lesiona | Genital HPV detected prior to lesion developmentb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BZ | PeIN 1 | Coronal Sulcus | 39/68/73 | 16/52/53/66/73/82 |

| MXc | PeIN 1 | Meatus | 11/51 | 11 |

| MXc | PeIN 1 | Meatus | 11 | 11 |

| US | PeIN 2 | Shaft Left Dorsal | 16 | 16 |

| US | PeIN 2 | Right Inguinal | 16 | 6/16/68 |

| MX | PeIN 2 | Shaft right ventral | 6/16 | 6/16/56/58 |

| BZ | PeIN 3 | Meatus | 6 | 6/73 |

| BZ | PeIN 3 | Shaft-Left Dorsal | 16 | 16/26/40/45/54/52/58/59/68 |

| BZ | PeIN 3 | Glans penis | 16 | 16/53/56/59 |

| MX | PeIN 3 | Shaft left ventral | 11/16 | 16/40 |

HPV genotyping results using the INNO-LiPA method with DNA extracted from FFPE biopsy tissue

HPV genotypes that were detected within the lesion are in bold.

Both specimens were diagnosed in a single participant

Discussion

Infection with one or more of the 37 HPV types detected at the genitals is common among men aged 18–70 years. Only 5% of these HPV infections progressed to an EGL during follow-up, rates of progression to an EGL were substantially higher for certain HPV types. Twenty-five percent of men with a genital HPV6 infection progressed to an HPV6-positive condyloma, and 23% of men with a genital HPV11 infection progressed to an HPV11-positive condyloma, with rapid rates of progression to disease after initial genital infection.

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to examine in men the type-specific genital HPV progression to histologically confirmed EGL with the same HPV type detected within the lesion. We (24) and others (25–27) previously reported the incidence of genital warts (14.6%–58% 24-month cumulative incidence) and HPV type distribution based on visual inspection, and recently published the genotype and age-specific incidence of histopathologically confirmed lesions (12). Although some previous reports of HPV incidence were based on detection from swabs of the surface of the lesion, the current analysis focuses on HPV detected within the lesion, which is more likely the causal HPV type (22, 28).

A diversity of HPV genotypes (31/33/45/52/56/58/26/73/82) were detected in genital skin specimens from the men in this study; however, few were detected within EGLs. Although they may infrequently progress to lesions in men, these other HPV types are likely transmitted to female partners, increasing the risk of HPV 31-/33-/45-/52-/58-positive cervical lesions. Vaccinating males and females with the recently approved 9-valent HPV vaccine (types 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52/58) would reduce the overall HPV infection burden, and ultimately disease, in both genders (29).

We are presenting the first estimates of genital HPV infection progression to PeIN. Although we expected PeIN to be a rare event even in populations with higher incidence of penile cancer, the sample size for PeIN (10 lesions in 9 men) limited the types of analyses that could be performed. The conclusions are valid, given that we are following a type-specific HPV infection at the genitals and detecting that same HPV type within a lesion that developed. We are the first to follow these HPV infections as they progress to a lesion in men. Of the nine men with a PeIN lesion, four were from Brazil, three from Mexico, and two from the U.S. Although we are not statistically powered to assess HPV progression to PeIN by country, the most PeIN lesions were diagnosed among men from Brazil. Brazil has the highest incidence of penile cancer compared to the U.S. and Mexico (8); however, this cancer is rare even in high-risk countries, where penile cancer accounts for up to 10% of all male cancers. Our methods of detecting genital lesions, visual inspection with 3x magnification without aceto-whitening, may have led to an under ascertainment of PeIN. We considered aceto-whitening prior to examination but were concerned that this would result in poor specificity for PeIN (30), leading to a high rate of unnecessary and invasive biopsy procedures.

We also may be underestimating the proportion of genital HPV infections that progress to condyloma, as progression to condyloma may have occurred in the six months between visits. When we assessed whether the HPV types detected in condyloma were present at the genitals prior to condyloma development, only 69% of all HPV types detected in condyloma were present previously at the genitals (data not shown). While 17% of those condylomas did not have any of the HPV types detected within the condyloma present at the genitals prior to condyloma development, this may be explained by the fact that previous estimates suggest that the incubation time from HPV infection to condyloma is 2 weeks to 8 months (8, 31). We tested for genital HPV infection every six months and it is likely that some infections progressed to condyloma within the short time frame between study visits. Surprisingly, two of the PeIN lesions also did not have the HPV types detected within the lesion in prior genital specimens. Types detected within these two PeIN lesions were HPV6 and HPV11/18/39. Further studies with short duration between follow-up visits may be able to capture these additional HPV types, although six months between visits is most often used in HPV natural history cohorts.

Conclusions

Genital HPV 6 and 11 infections were the infections most likely to progress to condyloma, and genital HPV 6, 11 and 16 infections were the infections most likely to progress to PeIN. The quadrivalent (6/11/16/18) HPV (qHPV) vaccine contains the most common HPV types (6/11/16) that we found to progress to EGL. The qHPV vaccine has been shown to be efficacious in preventing condyloma and, likely, PeIN(32). With the national qHPV vaccine program in Australia, condyloma incidence among men in the vaccination age group (< 21 years) has significantly decreased compared to those outside of the vaccination age range (33), demonstrating the potential of vaccination to prevent these clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The HIM Study infrastructure is supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health [R01 CA098803 to A.R.G.]. S.L.S was supported by a Postdoctoral Cancer Prevention Fellowship [R25T CA147832] from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. C.M.P.C. was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship [PF-13-222-01-MPC] from the American Cancer Society.

The authors thank Jorge Salmeron and Manuel Quiterio for valuable comments on the manuscript. This work has been supported in part by the Biostatistics Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute; an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

A.R.G. is a current recipient of grant funding from Merck (IISP39582), and A.R.G. and L.L.V. are members of the Merck Advisory Board. J.L.M. is a consultant and receives personal fee from Myriad Corporation. No conflicts of interest were declared for any of the remaining authors.

References

- 1.IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Vol. 90. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007. Human papillomaviruses; pp. 1–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012;30 (Suppl 5):F12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055. Epub 2012/12/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacey CJ, Lowndes CM, Shah KV. Chapter 4: Burden and management of non-cancerous HPV-related conditions: HPV-6/11 disease. Vaccine. 2006;24 (Suppl 3):S3/35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.015. Epub 2006/09/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anic GM, Lee JH, Villa LL, et al. Risk factors for incident condyloma in a multinational cohort of men: the HIM study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205(5):789–93. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir851. Epub 2012/01/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Den Eeden SK, Habel LA, Sherman KJ, McKnight B, Stergachis A, Daling JR. Risk factors for incident and recurrent condylomata acuminata among men. A population-based study. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1998;25(6):278–84. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199807000-00002. Epub 1998/07/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Insinga RP, Dasbach EJ, Elbasha EH. Assessing the annual economic burden of preventing and treating anogenital human papillomavirus-related disease in the US: analytic framework and review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics. 2005;23(11):1107–22. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523110-00004. Epub 2005/11/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favorito LA, Nardi AC, Ronalsa M, Zequi SC, Sampaio FJ, Glina S. Epidemiologic study on penile cancer in Brazil. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2008;34(5):587–91. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382008000500007. discussion 91–3. Epub 2008/11/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anic GM, Giuliano AR. Genital HPV infection and related lesions in men. Preventive medicine. 2011;53 (Suppl 1):S36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.002. Epub 2011/10/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demeter LM, Stoler MH, Bonnez W, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical presentation and an analysis of the physical state of human papillomavirus DNA. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1993;168(1):38–46. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin MA, Kleter B, Zhou M, et al. Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in penile carcinoma: evidence for multiple independent pathways of penile carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(4):1211–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieland U, Jurk S, Weissenborn S, Krieg T, Pfister H, Ritzkowsky A. Erythroplasia of queyrat: coinfection with cutaneous carcinogenic human papillomavirus type 8 and genital papillomaviruses in a carcinoma in situ. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115(3):396–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingles DJ, Pierce Campbell CM, Messina JA, et al. HPV Genotype- and Age-specific Analyses of External Genital Lesions Among Men in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu587. Epub 2014/10/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Djajadiningrat RS, Jordanova ES, Kroon BK, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence in invasive penile cancer and association with clinical outcome. The Journal of urology. 2015;193(2):526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.08.087. Epub 2014/08/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heideman DA, Waterboer T, Pawlita M, et al. Human papillomavirus-16 is the predominant type etiologically involved in penile squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(29):4550–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3182. Epub 2007/10/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palefsky JM. Human papillomavirus-related disease in men: not just a women’s issue. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2010;46(4 Suppl):S12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.010. Epub 2010/03/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonpavde G, Pagliaro LC, Buonerba C, Dorff TB, Lee RJ, Di Lorenzo G. Penile cancer: current therapy and future directions. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2013;24(5):1179–89. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds635. Epub 2013/01/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moscicki AB, Schiffman M, Burchell A, et al. Updating the natural history of human papillomavirus and anogenital cancers. Vaccine. 2012;30 (Suppl 5):F24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.089. Epub 2012/12/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, et al. The human papillomavirus infection in men study: human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among men residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2008;17(8):2036–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0151. Epub 2008/08/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):932–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62342-2. Epub 2011/03/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1998;36(10):3020–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3020-3027.1998. Epub 1998/09/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. The lancet oncology. 2009;10(4):321–2. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. Epub 2009/04/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anic GM, Messina JL, Stoler MH, et al. Concordance of human papillomavirus types detected on the surface and in the tissue of genital lesions in men. Journal of medical virology. 2013;85(9):1561–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23635. Epub 2013/07/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ying Z, Wei L. The Kaplan-Meier estimate for dependent failure time observations. Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 1994;50(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anic GM, Lee JH, Stockwell H, et al. Incidence and human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution of genital warts in a multinational cohort of men: the HPV in men study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;204(12):1886–92. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir652. Epub 2011/10/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arima Y, Winer RL, Feng Q, et al. Development of genital warts after incident detection of human papillomavirus infection in young men. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;202(8):1181–4. doi: 10.1086/656368. Epub 2010/09/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreira ED, Jr, Giuliano AR, Palefsky J, et al. Incidence, clearance, and disease progression of genital human papillomavirus infection in heterosexual men. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014;210(2):192–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu077. Epub 2014/02/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel H, Wagner M, Singhal P, Kothari S. Systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of genital warts. BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-39. Epub 2013/01/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkins MG, Winder DM, Ball SL, et al. Detection of specific HPV subtypes responsible for the pathogenesis of condylomata acuminata. Virology journal. 2013;10:137. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-137. Epub 2013/05/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joura E V503-001 Study Team. Efficacy and Immunogenicity of a novel 9-valent HPV L1 virus-like particle vaccine in 16- to 26-year-old women. Eurogin Conference; Florence, Italy. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar B, Gupta S. The acetowhite test in genital human papillomavirus infection in men: what does it add? Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2001;15(1):27–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00196.x. Epub 2001/07/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oriel JD. Natural history of genital warts. The British journal of venereal diseases. 1971;47(1):1–13. doi: 10.1136/sti.47.1.1. Epub 1971/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV Infection and disease in males. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(5):401–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909537. Epub 2011/02/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2013;346:f2032. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2032. Epub 2013/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.