Abstract

The transcriptional regulation underlying the differentiation of CD8+ effector and memory T cells remains elusive. Here, we show that 18-month-old mice lacking the transcription factor Smad4 (homolog 4 of mothers against decapentaplegic, Drosophila), a key intracellular signaling effector for the TGF-β superfamily, in T cells exhibited lower percentages of CD44hiCD8+ T cells. To explore the role of Smad4 in the activation/memory of CD8+ T cells, 6- to 8-week-old mice with or without Smad4 in T cells were challenged with Listeria monocytogenes. Smad4 deficiency did not affect antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell expansion but led to partially impaired cytotoxic function. Less short-lived effector T cells but more memory-precursor effector T cells were generated in the absence of Smad4. Despite that, Smad4 deficiency led to reduced memory CD8+ T-cell responses. Further exploration revealed that the generation of central memory T cells was impaired in the absence of Smad4 and the cells showed survival issue. In mechanism, Smad4 deficiency led to aberrant transcriptional programs in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. These findings demonstrated an essential role of Smad4 in the control of effector and memory CD8+ T-cell responses to infection.

CD8+ cytotoxic T cells play pivotal roles in the clearance of intracellular pathogens.1, 2 Antigen-specific naive CD8+ T cells undergo a massive clonal expansion as they come in contact with their cognate antigen on activated antigen-presenting cells. Within the expanded clone, there exist distinct subsets that can be characterized by both function and phenotype. Cells expressing high levels of killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1) and low levels of IL-7 receptor-α (CD127) represent terminally differentiated, short-lived effector T cells (SLEC), whereas KLRG1lowCD127hi CD8+ T cells have a greater potential to enter into the memory pool.3, 4 In response to antigen restimulation, memory CD8+ T cells rapidly proliferate and differentiate into cytolytic T lymphocytes that confer enhanced protection against intracellular pathogens.

The transcriptional regulation of these cell-fate decisions has been an area of active research. It has been demonstrated that the T-box transcription factor T-bet (encoded by Tbx21) promotes CD8+ T-cell differentiation into short-lived effectors.5, 6 Eomesodermin (Eomes), B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6 (Bcl6), and T-cell factor 7 (Tcf7, also known as Tcf1, downstream transcription factor of the Wnt pathway) are required for important aspects of memory CD8+ T-cell generation.5, 7, 8, 9 In addition, B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp1, encoded by Prdm1) is essential for the differentiation of short-lived cytotoxic effector T cells and memory responses.10, 11 A recent study based on high-resolution microarray analyses has suggested that many other transcription factors are involved in these cell-fate decisions.12 Surprisingly, Smad4 (homolog 4 of mothers against decapentaplegic, Drosophila), a key intracellular signaling effector for the TGF-β superfamily, has been predicted as an activator.12, 13 Thus, it is of importance to identify the role of Smad4 in the differentiation of CD8+ effector and memory T cells. Here, we report that Smad4 is required for the differentiation of effector CD8+ T cells and memory responses.

Results

Eighteen-month-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice exhibit impaired CD44 expression in CD8+ T cells

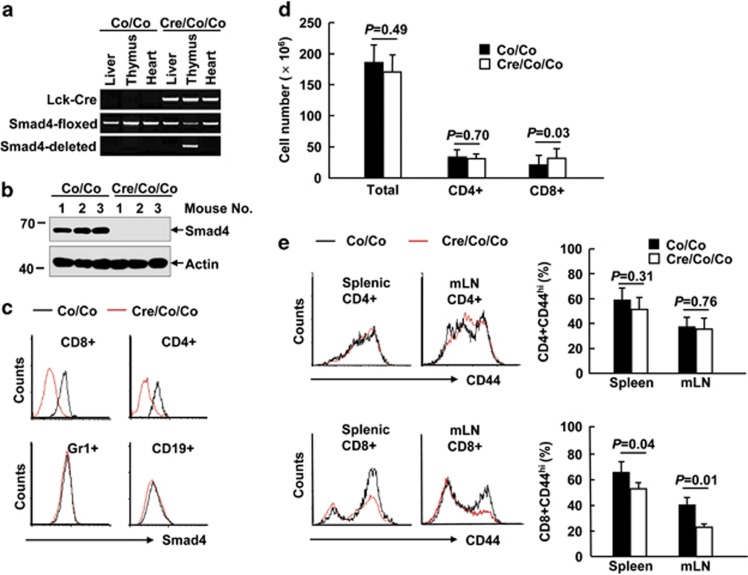

Specific inactivation of Smad4 in T cells was achieved by crossing mice homozygous for a Smad4 conditional allele (Smad4co/co)14, 15 with mice expressing a transgene encoding Cre recombinase driven by the lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (Lck) proximal promoter.16 Cre-mediated excision of exon 8 of the Smad4 gene was detected by PCR (Figure 1a). Smad4 deficiency in thymocytes and splenic T cells was confirmed by immunoblotting and intracellular Smad4 staining (Figures 1b and c). However, levels of Smad4 were unaltered in other types of immune cells (Figure 1c). Compared to their littermate controls, Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice exhibited unchanged numbers of CD4+ splenic T cells as well as total splenocytes until 18-month old (Figure 1d). Furthermore, peripheral CD4+ T cells in 18-month-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice showed no aberrant CD44 expression (Figure 1e). However, Smad4 deficiency in T cells led to about 50% more CD8+ splenic T cells in 18-month-old mice (Figure 1d). Moreover, 18-month-old mice lacking Smad4 in T cells showed lower percentages of CD44hiCD8+ T cells both in the spleen and in the mesenteric lymph node (mLN; Figure 1e), suggesting that Smad4 deficiency in T cells might cause a defect in the activation/memory of CD8+ T cells.

Figure 1.

Eighteen-month-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice exhibit impaired CD44 expression in CD8+ T cells. (a) Genotyping of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice (Cre/Co/Co) and control littermates (Co/Co). (b) The expression of Smad4 and actin in the thymocytes of 6- to 8-week-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and control littermates. IB, immunoblotting. (c) Flow cytometry analysis of Smad4 expression in splenic CD4+ T, CD8+ T, Gr1+, and CD19+ B cells of 6- to 8-week-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and control littermates. (d) The absolute numbers of total white cells, CD4+ T, and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, as revealed by white cell count and flow cytometry analysis, in 18-month-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and control littermates (n=6 per group). (e) Flow cytometry analysis of CD44 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen and mesenteric lymph node (mLN) of 18-month-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and control littermates (n=6 per group)

Unchanged antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell expansion in the absence of Smad4

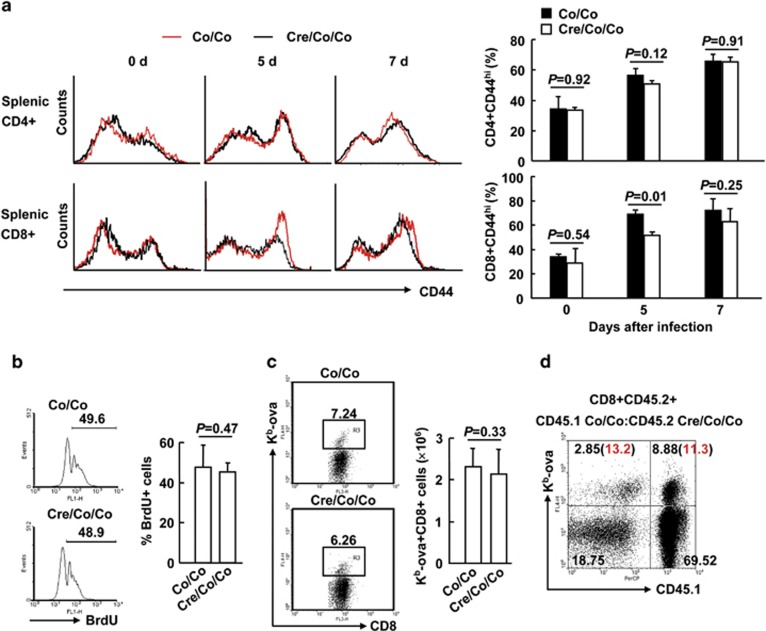

To explore the role of Smad4 in the activation of CD8+ T cells, we challenged 6- to 8-week-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls with ovalbumin-modified Listeria monocytogenes (LM-OVA). At this age, basal CD44 expression in either CD4+ or CD8+ splenic T cells was unchanged in the absence of Smad4 (Figure 2a). LM-OVA infection led to CD44 upregulation in both CD4+ and CD8+ splenic T cells as the spleen is the primary site of infection (Figure 2a). Even though CD44 upregulation in CD8+ splenic T cells was partially impaired in Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice at day 5 post infection, it recovered at day 7 (Figure 2a). Moreover, the proliferation and expansion of CD8+ splenic T cells was unaffected in the absence of Smad4 at this time point (Figure 2b). As for OVA-antigen-specific T-cell responses, the frequencies and numbers of Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells were comparable between Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls at day 7 post infection (Figure 2c). We also checked the proliferation of antigen-specific CD8+ splenic T cells at later time points. However, Smad4 deficiency did not affect the proliferation up to 14 days post infection (Supplementary Figure S1). To distinguish CD8+ T-cell-intrinsic or -extrinsic mechanisms underlying the unchanged antigen-specific T-cell expansion, we created mice with mixed bone marrow through transferring bone marrow cells from congenically marked Smad4co/co (CD45.1CD45.2) and Smad4co/co; Lck-Cre (CD45.2CD45.2) mice into lethally irradiated CD45.1CD45.1 mice. After 8 weeks of bone marrow reconstitution, mice were infected with LM-OVA and the frequencies of Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells were assessed 7 days after infection. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the frequencies of OVA-antigen-specific CD8+ T cells originating from the Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre bone marrow were similar to those of the Smad4co/co counterparts in the same recipients (Figure 2d and Supplementary Figure S2). Thus, Smad4 plays a marginal role in the activation and proliferation of CD8+ T cells.

Figure 2.

Unchanged antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell expansion in the absence of Smad4. (a–c) Six- to eight-week-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and control littermates mice were infected with 5 × 103 c.f.u. of LM-OVA (n=6 per group). (a) CD44 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ splenic T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at days 0, 5, and 7 post infection. (b) Mice received 1 mg thymidine analog 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) in 0.1 ml PBS via i.p. injection at day 6 post infection; BrdU incorporation in CD8+ splenic T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h later. (c) The numbers of Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry at day 7 post infection. (d) Bone marrow chimeric mice reconstituted with a mix of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre (CD45.2CD45.2) and Smad4co/co (CD45.1CD45.2) cells were infected with 5 × 103 c.f.u. of LM-OVA. Single-cell suspensions from the spleen were analyzed for the expression of CD45.1 and OVA specificity (Kb-ova) at day 7 post infection. Representative plot of gated CD8+CD45.2+ T cells from the spleen is shown (n=3). The number in the bracket indicates the percentage of the Kb-ova+ T cells in relation to CD8+ T cells of the same origin. Data shown in this figure are representative of at least three independent experiments

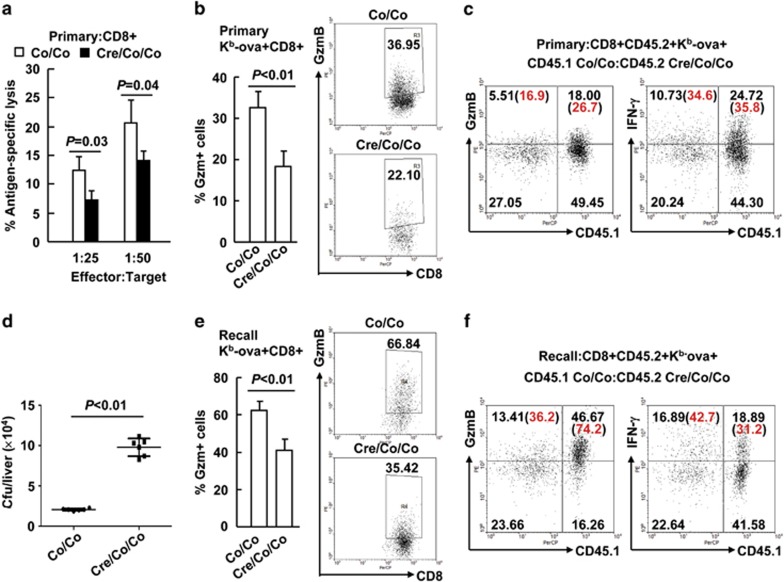

Smad4 contributes to the cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells

Next, whether Smad4 deficiency impacts on effector functions was explored 7 days after LM-OVA primary infection. Interestingly, Smad4-deficient CD8+ splenic T cells were partially impaired in their antigen-specific cytolytic activity (Figure 3a). Consistently, granzyme B (GzmB), the major mediator of CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity, was partially absent from Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells upon restimulation with the SIINFEKL peptide (Figure 3b). To distinguish CD8+ T-cell-intrinsic or -extrinsic mechanisms underlying the defective GzmB expression, bone marrow chimeric mice stated above were analyzed at day 7 post infection of LM-OVA. Intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that GzmB expression, but not interferon γ (IFN-γ) expression, in Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells was lower than that in competing Smad4-sufficient cells upon OVA peptide restimulation (Figure 3c and Supplementary Figure S3). Thus, Smad4 contributes to the cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells in primary infection.

Figure 3.

Smad4 is required for the cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells. (a and b) Six- to eight-week-old Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls were infected with 5 × 103 c.f.u. of LM-OVA (n=6 per group). Single-cell suspensions from the spleen were prepared on day 7. (a) CD8+ cytotoxic activity was measured by specific killing of OVA peptide-loaded EL-4 cells. Peptide unloaded EL-4 cells were used as negative control. (b) GzmB expression in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells upon restimulation with the SIINFEKL peptide (10 nM, 6 h) was analyzed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. (c) Bone marrow chimeric mice were prepared and treated as described in Figure 2d. The expression of CD45.1 and GzmB in Kb-ova+CD8+CD45.2+ splenic T cells at day 7 post infection upon OVA peptide restimulation was analyzed (n=3). (d and e) Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermates were rechallenged with 1 × 105 c.f.u. of LM-OVA 35 days after primary infection (n=6 per group). (d) Bacterial burden in the liver was determined 2 days after the secondary infection. (e) GzmB expression in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells upon OVA peptide restimulation was analyzed 5 days after the secondary infection. (f) Bone marrow chimeric mice were rechallenged with 1 × 105 c.f.u. of LM-OVA 35 days after primary infection. The expression of CD45.1 and GzmB in Kb-ova+CD8+CD45.2+ splenic T cells upon OVA peptide restimulation was analyzed 5 days after the secondary infection (n=3). Data shown in this figure are representative of at least three independent experiments

To explore whether Smad4 also controls the generation of cytotoxic effector cells from memory CD8+ T cells, we challenged Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermates with a higher dose of LM-OVA 35 days after primary infection. The bacterial burden in the liver, another primary site of infection, was examined 2 days after the secondary infection. Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice had about fivefold more Listeria colony-forming units (c.f.u.) than their littermate controls (Figure 3d), suggesting Smad4 deficiency led to defective generation of cytotoxic effector cells from memory CD8+ T cells. Consistently, Smad4 deficiency led to partially diminished GzmB expression in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells upon OVA peptide restimulation 5 days after the secondary infection (Figure 3e). Despite that, Smad4-deficient antigen-specific CD8+ T cells showed unaffected expression of IFN-γ and TNF-α under the same conditions (Supplementary Figure S4). For bone marrow chimeric mice, intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells exhibited decreased GzmB expression, but statistically unaffected IFN-γ expression, upon OVA peptide restimulation 5 days after the secondary infection, as compared to competing Smad4-sufficient cells (Figure 3f and Supplementary Figure S5). Thus, Smad4 also contributes to the cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells in recall responses.

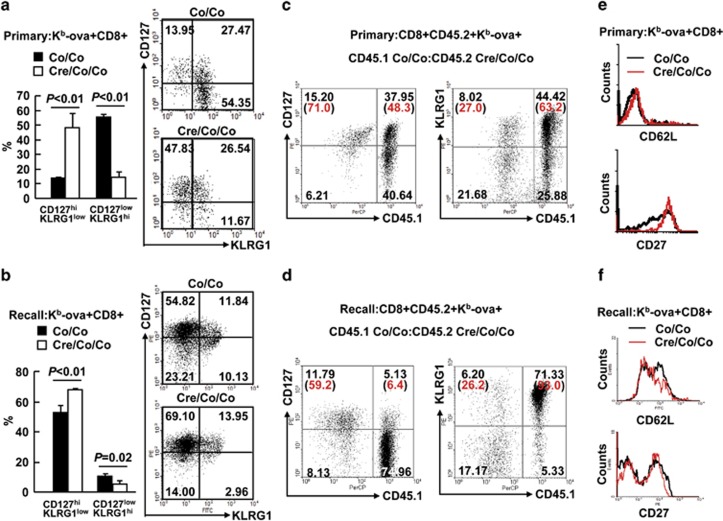

Smad4-deficient T cells show aberrant CD8+ T-cell differentiation

At the peak of the primary immune response to LM-OVA, about 55% Smad4-sufficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells expressed high amounts of KLRG1 and downregulated CD127 (Figure 4a), characteristics of SLEC. However, this number dropped to about 15% for their Smad4-deficient counterparts (Figure 4a). These data are consistent with our previous finding that Smad4 is required for the cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells. However, about 15% Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells in Smad4co/co mice were CD127hiKLRG1low, characteristics of memory-precursor effector cells (MPECs). This number increased to about 50% for their Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre counterparts (Figure 4a). To make it clear whether the Smad4-deficient CD8+ T cells maintain or re-express CD127 at high level at day 7 post infection of LM-OVA, we checked CD127 expression at earlier time points. We found that basal CD127 expression in CD8+ splenic T cells was unchanged in the absence of Smad4 (Supplementary Figure S6). At day 5 post infection of LM-OVA, a small portion of CD8+ splenic T cells in Smad4co/co mice began to downregulate CD127. However, Smad4-deficient CD8+ splenic T cells showed no downregulation (Supplementary Figure S6). Thus, Smad4-deficient CD8+ T cells maintain high CD127 expression after LM-OVA infection. The failure to upregulate KLRG1 and the maintenance of high CD127 expression was a uniform feature of Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells as revealed by the fact that it occurred in both primary (Figure 4a) and recall responses (Figure 4b). Importantly, analysis of infected bone marrow chimeric mice at the same time points indicates that such a feature is CD8+ T-cell intrinsic (Figures 4c and d; Supplementary Figures S7 and S8). Despite the significant accumulation of the CD127hiKLRG1low subset, flow cytometry analysis indicated that Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells exhibited enhanced expression of CD27, a cell-surface marker highly expressed in MPECs and has a pivotal role in the control of memory T-cell responses,17 only in primary (Figure 4e) but not in recall responses (Figure 4f). As for CD62L, another cell-surface marker essential for the control of memory T-cell responses,18 Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells failed to show enhanced expression of CD62L in both primary and recall responses (Figures 4e and f). These data suggest that Smad4 deficiency leads to aberrant CD8+ T-cell differentiation.

Figure 4.

Smad4-deficient T cells show aberrant CD8+ T-cell differentiation. (a) The expression of CD127 and KLRG1 in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls on day 7 of LM-OVA primary infection (n=6 per group). (b) The expression of CD127 and KLRG1 in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls 5 days after the secondary infection (n=6 per group). (c) Bone marrow chimeric mice were prepared and treated as described in Figure 2d. The expression of CD45.1 and CD127 or KLRG1 in Kb-ova+CD8+CD45.2+ splenic T cells at day 7 post infection was analyzed by flow cytometry (n=3). (d) Bone marrow chimeric mice were rechallenged with 1 × 105 c.f.u. of LM-OVA 35 days after primary infection. The expression of CD45.1 and CD127 or KLRG1 in Kb-ova+CD8+CD45.2+ splenic T cells 5 days after the secondary infection was analyzed by flow cytometry (n=3). (e) The expression of CD62L and CD27 in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls on day 7 of LM-OVA primary infection (n=6 per group). (f) The expression of CD62L and CD27 in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls 5 days after the secondary infection. Data shown in this figure are representative of at least three independent experiments

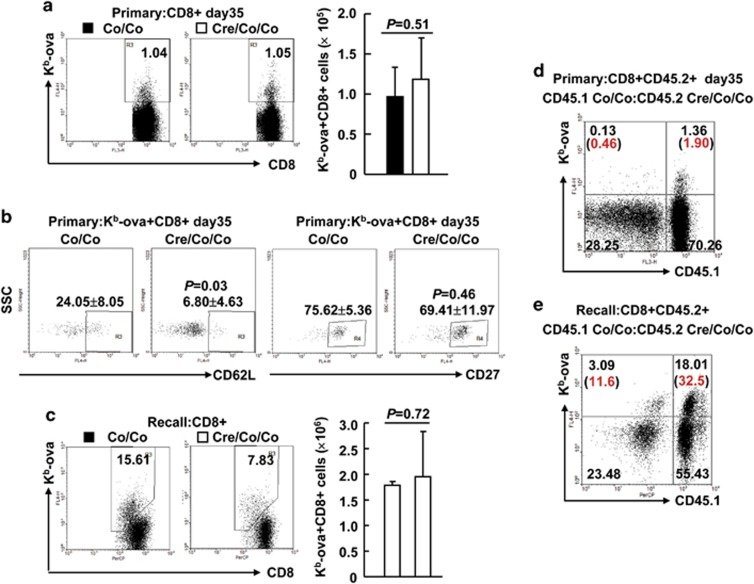

Smad4-deficiency leads to defective memory

Smad4 deficiency partially affected effector T-cell differentiation and led to the accumulation of MPECs without the proper expression of certain cell-surface markers. To understand the effect of Smad4 loss on memory, we analyzed the proportion of OVA antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells in Smad4-sufficient and -deficient CD8+ splenic T cells 35 days after primary infection. Neither the frequency nor the number of Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells was significantly different from that of control cells (Figure 5a). Smad4 deficiency showed no effect on CD27 expression, but led to diminished CD62L expression, in antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells 35 days after primary infection (Figure 5b). In line with this, the frequency and the number of Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells were similar to those of control cells 5 days after the secondary infection (Figure 5c). Thus, the accumulation of MPECs did not result in enhanced memory. To further address this issue, infected bone marrow chimeric mice were analyzed at the same time points. We found that the frequencies of Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells originating from the Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre bone marrow were lower than those of Smad4co/co counterparts in the same recipients 35 days after primary infection (Figure 5d and Supplementary Figure S9). Upon LM-OVA rechallenge, the ratios of Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells to competing Smad4-sufficient counterparts were further decreased (Figure 5e and Supplementary Figure S10). Taken together, these observations reveal a cell-intrinsic role for Smad4 in CD8+ T-cell memory.

Figure 5.

Smad4 deficiency leads to defective memory. (a) The percentages and numbers of Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells in Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls on day 35 of LM-OVA primary infection (n=6 per group). (b) The expression of CD62L and CD27 in Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls on day 35 of LM-OVA primary infection (n=6 per group). (c) The percentages and numbers of Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells in Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls 5 days after the secondary infection (n=6 per group). (d) Bone marrow chimeric mice were prepared and treated as described in Figure 2d. The expression of CD45.1 and OVA specificity (Kb-ova) in CD8+CD45.2+ splenic T cells at day 35 post infection was analyzed by flow cytometry (n=3). (e) Bone marrow chimeric mice were rechallenged with 1 × 105 c.f.u. of LM-OVA 35 days after primary infection. The expression of CD45.1 and OVA specificity (Kb-ova) in CD8+CD45.2+ splenic T cells 5 days after the secondary infection was analyzed by flow cytometry (n=3). Data shown in this figure are representative of at least three independent experiments

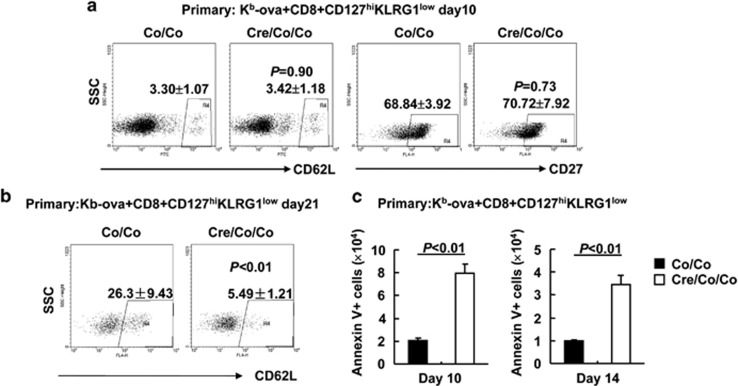

Smad4 contributes to the differentiation of central memory T cells by promoting the survival of MPECs

Next, we tried to explore why Smad4 deficiency leads to defective CD8+ T-cell memory despite of MPEC accumulation. We first checked the upregulation of central memory T-cell markers CD62L and CD27 on MPECs. At day 10 post infection of LM-OVA, Smad4-sufficient and -deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ CD127hiKLRG1low splenic T cells showed comparable percentages of CD27hi cells (68.84±3.92% versus 70.72±7.92% Figure 6a). As CD62L was only marginally upregulated on MPECs under the same conditions (Figure 6a), we also checked CD62L expression on day 21 post infection. As expected, CD62L was significantly upregulated in Kb-ova+CD8+CD127hiKLRG1low splenic T cells at this time point (Figure 6b). However, its upregulation was impaired upon Smad4 deficiency (Figure 6b). These facts pushed us to examine the survival of MPECs of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls. As shown in Figure 6c, Kb-ova+CD8+ CD127hiKLRG1low splenic T cells showed impaired survival in the absence of Smad4. Thus, central memory T cells were generated normally in absence of Smad4 but the cells showed survival issue.

Figure 6.

Smad4 contributes to the differentiation of central memory T cells by promoting the survival of MPECs. (a and b) The expression of CD62L and CD27 in Kb-ova+CD8+CD127hiKLRG1low splenic T cells of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls on day 10 (a) or day 21 (b) of LM-OVA primary infection (n=6 per group). (c) Apoptosis analysis of Kb-ova+CD8+CD127hiKLRG1low splenic T cells of Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls on days 10 and 14 of LM-OVA primary infection (n=6 per group). Data shown in this figure are representative of at least three independent experiments

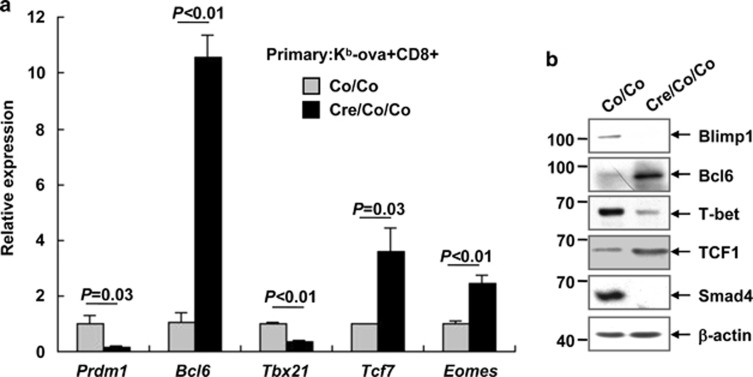

Smad4 regulates the transcriptional program in antigen-specific T cells

A small number of transcription factors, including Blimp1 (Prdm1), Bcl6, T-bet (Tbx21), Tcf7, and Eomes, are known to be important in the regulation of effector and memory CD8+ T-cell differentiation.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells expressed reduced levels of Prdm1 and Tbx21 transcripts but enhanced levels of Bcl6, Tcf7, and Eomes transcripts 7 days after LM-OVA primary infection, as compared to Smad4-sufficient counterparts (Figure 7a). Immunoblotting analysis of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells purified at the same time point indicated the same tendency (Figure 7b). These data suggest that Smad4 is required to establish the transcriptional profile essential for proper CD8+ T-cell differentiation.

Figure 7.

Smad4 regulates the transcriptional program in antigen-specific T cells. (a and b) Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells were sorted from Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls on day 7 of LM-OVA primary infection. Three to four biologically independent samples with the same genotype were mixed together and the experiment was repeated three times (a). Cells were then subjected to quantitative RT-PCR for the indicated transcripts. Data are shown as the expression relative to that found in Smad4-sufficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells (arbitrarily set to 1). (b) Cell lysates were then prepared and subjected to immunoblotting analysis with the indicated antibodies

Discussion

Smad4 is a key intracellular signaling effector for the TGF-β superfamily.13 TGF-β via Smad4 drives IL-10 expression in Th1 cells, IL-9 expression in Th9 cells, and IgA expression in B cells.19, 20, 21 It is reasonable to expect that mice with specific inactivation of Smad4 in T cells phenotypically resemble T-cell-specific TGF-βR-deficient mice and develop autoimmunity.22, 23 However, previous reports have demonstrated that Smad4 deficiency in T cells leads to proliferative epithelial lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, but not autoimmunity.24, 25 Consistently, people with germline mutations of Smad4 predispose to familial juvenile polyposis and gastrointestinal cancers but not some autoimmune diseases.26, 27 These facts suggest that Smad4 has TGF-β-independent functions in T cells. Indeed, a recent study has demonstrated that Smad4 contributes to T cells function during autoimmunity and anti-tumor immunity independent of TGF-βR signaling.28

CD8+ cytotoxic T cells play pivotal roles in autoimmunity and anti-tumor immunity as well as the clearance of intracellular pathogens. It has been revealed that Smad4 is essential for the development of central memory CD8+ T cells whereas TGF-β is dispensable.29 However, the underlying mechanisms by which Smad4 promotes the development of central memory CD8+ T cells remain unknown, and no data have been shown about the role of Smad4 in cytokine production of CD8+ T cells. Here, we confirm that Smad4 deficiency leads to reduced memory CD8+ T-cell responses. Further exploration revealed the accumulation of memory-precursor effector T cells in the absence of Smad4. Then, we have disclosed that defective survival leads to defective generation of central memory T cells in the absence of Smad4 due to aberrant transcriptional programs. Moreover, we show Smad4 deficiency partially impairs the production of GzmB, the major mediator of CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity. These functions of Smad4 might contribute to its critical role in preventing tumor development.

In our model, Smad4 is deficient not only in CD8+ T cells but also in CD4+ T cells. Because of the essential effects of Smad4 in the control proper CD4+ T-cell differentiation,19, 20, 28 consequently changes in CD4+ T cell help or Treg function could alter the course of infection. Indeed, there are fewer Smad4-deficient Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells than competing Smad4-sufficient counterparts in chimeras 35 days post infection, while the frequencies and numbers of Kb-ova+CD8+ splenic T cells are comparable between Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice and their littermate controls at the same time point. The changed microenvironment in Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice might contribute to the difference. Similarly, the changed microenvironment in Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice might also blur the bacteria burdens measured 5 days after the secondary infection. The data obtained from chimeras are more convincing. This approach ensures that Smad4-deficient and Smad4-sufficient CD8+ T cells are exposed to identical concentrations of antigen and inflammation during infection. Therefore, whether defective generation of central memory T cells associated with survival issue in Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice is cell-intrinsic defects should be further confirmed with chimeras in the future. With chimeras, we have observed both defective memory and impaired production of GzmB in the absence of Smad4, consistent with the data obtained from Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre mice despite of minor differences. The use of different mixed bone marrow chimeras and analysis at different time points after infection would make the conclusions more convincing.

Improved understanding of the generation of effector and memory CD8+ T cells during the immune response could be used to augment vaccine-induced immunity. Our findings suggest manipulating Smad4 functions might facilitate the control of infection, autoimmunity, and cancer. The TGF-β-independent functions of Smad4 in CD8+ T-cell differentiation may be downstream of signaling, which begins with the receptor for bone morphogenic protein or another unidentified cytokine. The source of such a cytokine may be T cells and other types of cells in the microenvironment. Enhancing or suppressing the production of such a cytokine might be an easy way to control infection, autoimmunity, and cancer.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice homozygous for a Smad4 conditional allele (Smad4co/co) were previously described14, 15 and were all backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background. Mice expressing a transgene encoding Cre recombinase driven by Lck proximal promoter were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Specific inactivation of Smad4 in T cells was achieved by crossing Smad4co/co mice with Lck-Cre mice. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and animals were handled in accordance with institutional guidelines. Genotyping was performed as described previously.30

Listeria monocytogenes infection

For the study of primary immune response, mice were intravenously infected with 5 × 103 c.f.u. of LM-OVA. For the analysis of secondary immune response, mice were rechallenged with 1 × 105 c.f.u. of LM-OVA 35 days after primary infection.

BrdU incorporation

Staining of BrdU incorporation followed the BrdU Flow kit protocol (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). Briefly, cells were dehydrated in an alcohol solution, fixed and permeabilized in 1% paraformaldehyde/0.01% Tween 20, treated with 50 U/ml DNase, and then stained with 10 μl of FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU (Becton Dickinson).

Colony-forming unit assay

Single-cell suspensions were made from livers in PBS containing 0.01% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The supernatants were inoculated on brain-heart-infusion agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Bacterial colonies were counted.

Flow cytometry

Fluorescent-dye-labeled antibodies against cell-surface markers CD4, CD8, CD44, CD62L, Gr1, CD19, CD45.1, CD45.2, CD127, CD27, and KLRG1 were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). FITC- or PE-conjugated antibodies against cytokines were from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). APC- or PE-conjugated Kb-ova+ tetramer was obtained from QuantoBio (Beijing, China). Splenic cells were depleted of erythrocytes by hypotonic lysis. The cells were washed with FACS washing buffer (2% FBS, 0.1% NaN3 in PBS) twice and were then incubated with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against cell-surface molecules for 30 min on ice in the presence of 2.4G2 mAb to block FcγR binding. Isotype antibodies were included as negative controls. For intracellular cytokine staining, single-cell suspensions were stimulated with 10 nM SIINFEKL peptide in the presence of Brefeldin A solution (eBioscience) for 6 h at 37 °C. After stimulation, cells were stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against cell-surface markers, fixed, and permeabilized using a fixation/permeabilization kit (eBioscience) and stained with fluorescence-conjugated specific antibodies against Smad4 (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), IFN-γ, TNF-α, and GzmB in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry was performed using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur machine.

Antibodies and immunoblotting

Antibodies against Blimp1 (9115 S, encoding by Prdm1) and TCF-1 (2203S, encoding by Tcf7) were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies against Smad4 (sc-7966) and β-actin (sc-8432) were obtained from Santa Cruz. Antibodies against Bcl6 (648301) and T-bet (644801, encoding by Tbx21) were obtained from BioLegend. Total protein extracts were prepared and dissolved in SDS sample buffer. Protein extracts were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were probed with antibodies and visualized with an electrochemiluminescence kit (Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden).

Generation of bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow cells were depleted of T cells and antigen-presenting cells by complement-mediated cell lysis. Smad4co/co and Smad4co/co;Lck-Cre bone marrow cells (2 × 106) were cotransferred into lethally irradiated recipients (1200 rads). The congenic markers CD45.1 and CD45.2 were used for distinguishing cells from different donors and recipients.

Cytotoxicity assays

CD8+ cytotoxic function was analyzed using flow cytometry as described previously.31, 32 Briefly, single-cell suspensions from the spleen were prepared on day 7 of LM-OVA infection. Purified CD8+ T cells were used as effector cells. EL-4 cells were pulsed with 2 μM OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL) peptide at 37 °C for 1 h. Peptide-pulsed EL-4 cells were used as target cells with unpulsed EL-4 cells as negative control. Target cells (2 × 104 per well) were cocultured with effector cells in 96 U-bottom plates at 25 : 1 and 50 : 1. After incubation for 6 h at 37 °C, cells were collected and stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V, PERCP-conjugated anti-CD8 and propidium iodide (PI), followed by flow cytometry. Specific lysis (%) was calculated as follows: CD8− cells minus CD8-annexin V-PI− cells/CD8− cells × 100. Spontaneous apoptosis was <10% for all experiments.

Apoptosis analysis

Single-cell suspensions from the spleen were prepared on days 10 and 14 of LM-OVA infection. Purified CD8+ T cells were stained with anti-Kb-ova-PE, anti-KLGR1-FITC, anti-CD127-PERCP, and annexin V-APC resuspended in 300 μl binding buffer containing calcium ion. Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of annexin-V staining in Kb-ova+CD8+ CD127hiKLRG1low splenic T cells.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). First-strand synthesis was performed with oligo-dT primers, and reverse transcription was performed with M-MLV reverse transcriptase. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green reagent (TOYOBO, Tokyo, Japan) in a real-time PCR machine Realplex 2 (Eppendorf, Hamberg, Germany). Reactions were performed three times independently, and GAPDH values were used to normalize gene expression. Primers for murine Prdm1, Bcl6, and Tbx21;11 primers for murine Eomes;10 and primers for murine Tcf733 have been reported previously. Primers for GAPDH were 5′-ggcaaattcaacggcacagt-3′ (forward) and 5′-agatggtgatgggcttccc-3′ (reverse).

Statistics

Results are shown as mean±S.D. Differences were considered significant with a P-value <0.05 using Student's t-test (paired or unpaired) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Youwen He (Duke University) for helpful discussion. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81472736 and 31270960) to JZ.

Glossary

- KLRG1

killer cell lectin-like receptor G1

- SLEC

short-lived effector T cells

- Eomes

eomesodermin

- Bcl6

B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6

- Tcf7

T-cell factor 7

- Blimp1

B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1

- mLN

mesenteric lymph node

- GzmB

granzyme B

- MPECs

memory-precursor effector cells

- Lck

lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase

- c.f.u.

colony-forming units

- LM-OVA

ovalbumin-modified Listeria monocytogenes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by G Amarante-Mendes

Supplementary Material

References

- 1Klenerman P, Hill A. T cells and viral persistence: lessons from diverse infections. Nat Immunol 2005; 6: 873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Thaventhiran JE, Fearon DT, Gattinoni L. Transcriptional regulation of effector and memory CD8+ T cell fates. Curr Opin Immunol 2013; 25: 321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 1191–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Sarkar S, Kalia V, Haining WN, Konieczny BT, Subramaniam S, Ahmed R. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J Exp Med 2008; 205: 625–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol 2005; 6: 1236–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity 2007; 27: 281–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Ichii H, Sakamoto A, Hatano M, Okada S, Toyama H, Taki S et al. Role for Bcl-6 in the generation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol 2002; 3: 558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Jeannet G, Boudousquié C, Gardiol N, Kang J, Huelsken J, Held W. Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 9777–9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Zhou X, Yu S, Zhao DM, Harty JT, Badovinac VP, Xue HH. Differentiation and persistence of memory CD8(+) T cells depend on T cell factor 1. Immunity 2010; 33: 229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Kallies A, Xin A, Belz GT, Nutt SL. Blimp-1 transcription factor is required for the differentiation of effector CD8+ T cells and memory responses. Immunity 2009; 31: 283–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Rutishauser RL, Martins GA, Kalachikov S, Chandele A, Parish IA, Meffre E et al. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 promotes CD8+ T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity 2009; 31: 296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Best JA, Blair DA, Knell J, Yang E, Mayya V, Doedens A et al. Transcriptional insights into the CD8(+) T cell response to infection and memory T cell formation. Nat Immunol 2013; 14: 404–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature 1997; 390: 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Li F, Lan Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Yang G, Meng F. Endothelial smad4 maintains cerebrovascular integrity by activating N-Cadherin through cooperation with Notch. Dev Cell 2011; 20: 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Yang X, Li C, Herrera PL, Deng CX. Generation of Smad4/Dpc4 conditional knock out mice. Genesis 2002; 32: 80–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Orban PC, Chui D, Marth JD. Tissue- and site-specific DNA recombination in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992; 89: 6861–6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Hendriks J, Gravestein LA, Tesselaar K, van Lier RA, Schumacher TN, Borst J. CD27 is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity. Nat Immunol 2000; 1: 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Hikono H, Kohlmeier JE, Takamura S, Wittmer ST, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. Activation phenotype, rather than central- or effector-memory phenotype, predicts the recall efficacy of memory CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med 2007; 204: 1625–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Huss DJ, Winger RC, Cox GM, Guerau-de-Arellano M, Yang Y, Racke MK et al. TGF-β signaling via Smad4 drives IL-10 production in effector Th1 cells and reduces T cells trafficking in EAE. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41: 2987–2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Wang A, Pan D, Lee YH, Martinez GJ, Feng XH, Dong C. Smad2 and Smad4 regulate TGF-β-mediated Il9 gene expression via EZH2 displacement. J Immunol 2013; 191: 4908–4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Park SR, Lee JH, Kim PH. Smad3 and Smad4 mediate transforming growth factor-b1-induced IgA expression in murine B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol 2001; 31: 1706–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Liu Y, Zhang P, Li J, Kulkarni AB, Perruche S, Chen W. A critical function for TGF-beta signaling in the development of natural CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2008; 9: 632–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Marie JC, Letterio JJ, Gavin M, Rudensky AY. TGF-beta1 maintains suppressor function and Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2005; 201: 1061–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Hahn JN, Falck VG, Jirik FR. Smad4 deficiency in T cells leads to the Th17-associated development of premalignant gastroduodenal lesions in mice. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 4030–4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Kim BG, Li C, Qiao W, Mamura M, Kasprzak B, Anver M et al. Smad4 signalling in T cells is required for suppression of gastrointestinal cancer. Nature 2006; 441: 1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Howe JR, Roth S, Ringold JC, Summers RW, Jarvinen HJ, Sistonen P et al. Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science 1998; 280: 1086–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Miyaki M, Kuroki T. Role of Smad4 (DPC4) inactivation in human cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 306: 799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Gu AD, Zhang S, Wang Y, Xiong H, Curtis TA, Wan YY. A critical role for transcription factor Smad4 in T cell function that is independent of transforming growth factor β receptor signaling. Immunity 2015; 42: 68–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Hu Y, Lee YT, Kaech SM, Garvy B, Cauley LS. Smad4 promotes differentiation of effector and circulating memory CD8 T cells but is dispensable for tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol 2015; 194: 2407–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Meng F, Shi L, Cheng X, Hou N, Wang Y, Teng Y et al. Surfactant protein A promoter directs the expression of Cre recombinase in brain microvascular endothelial cells of transgenic mice. Matrix Biol 2007; 26: 54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Wherry EJ, Teichgräber V, Becker TC, Masopust D, Kaech SM, Antia R et al. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Xu S, Han Y, Xu X, Bao Y, Zhang M, Cao X. IL-17A-producing gammadelta T cells promote CTL responses against Listeria monocytogenes infection by enhancing dendritic cell cross-presentation. J Immunol 2010; 185: 5879–5887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Kim MV, Ouyang W, Liao W, Zhang MQ, Li MO. The transcription factor Foxo1 controls central-memory CD8+ T cell responses to infection. Immunity 2013; 39: 286–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.