Abstract

A paper recently published in Science reports that adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1-dependent adenosine-to-inosine editing marks endogenous double strand RNA as self and prevents their immune recognition by cytosolic RNA sensor MDA5.

To distinguish non-self from self is the core mission of immune system. The innate immune system is the first line of defense that defends host from invasion by pathogenic microorganism. In response to exogenous RNAs derived from invading pathogens, host immune system can detect the pathogenic RNAs via cytosolic RNA sensors, such as retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I), melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 (MDA5) and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2), and initiate the downstream signaling pathway1. However, recognition of endogenous RNAs in the cytoplasm by these sensors should be avoided. How to mark endogenous dsRNA as “self” while recognize exogenous dsRNA as “non-self” is a dilemma for immune system. Now Liddicoat et al.2 showed in a recent Science paper that ADAR1 can mediate the adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) editing of self dsRNA and thus avoid the recognition of endogenous dsRNA by MDA5.

RNA editing is a molecular process through which cells can make discrete changes to specific nucleotide sequences within a RNA molecule. In humans, the most common type of RNA editing is adenosine to inosine3, which is catalyzed by the ADAR proteins4. The study by Liddicoat et al.2 links RNA editing to RNA recognition, providing an explanation for unresponsiveness of RNA sensors like MDA5 to endogenous dsRNA and highlighting a crucial physiological role of ADAR1.

In 2008, the Walkley group reported that ADAR1 is essential for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and suppression of interferon (IFN) signaling5. Loss of ADAR1 in HSCs led to global upregulation of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) and rapid apoptosis. However, the exact mechanism is unclear. To address this, the Walkley lab generated a constitutive knock-in of an editing-deficient ADAR1E861A allele in mice. Compared to wild-type mice, the Adar1E861A/E861A mice died at ∼E13.5, and the size of fetal liver was smaller and contained massive apoptotic cells. Three hundred eighty-three transcripts were upregulated in Adar1E861A/E861A fetal liver, and most of them (258 of 383) were ISGs. The phenotypes of Adar1E861A/E861A mice were analogous to those with ADAR1 deficiency. By comparing the gene set associated with the response to IU-dsRNA (inosine uracil-paired dsRNA) in human cells, they found that the gene signatures (most of them were ISGs) of both Adar1E861A/E861A fetal liver and Adar1−/− HSCs were highly enriched for the IU-dsRNA response. Thus the authors proposed that the A-to-I RNA editing catalyzed by ADAR1 was a key step for suppression of the IFN response.

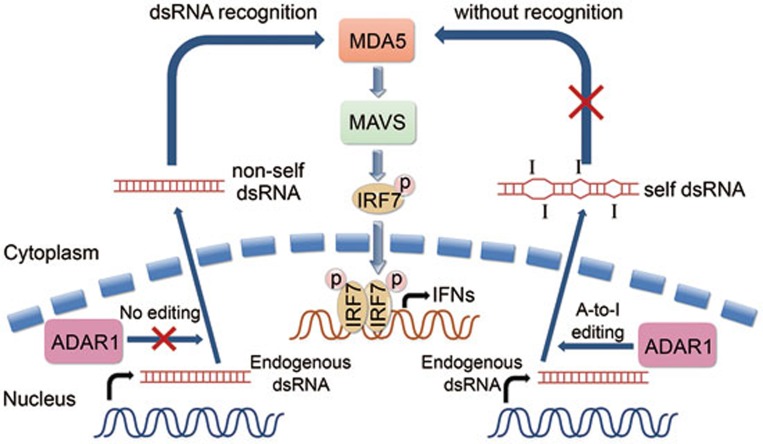

To determine the ADAR1-specific RNA editing events in vivo, Liddicoat et al. analyzed A-to-I mismatches from RNA-seq data. Among the edited RNA transcripts, there were three hyper-edited transcripts (klf1, optn, oip5) and their ADAR1-specific A-to-I hyper-edited sites were located within long 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTRs). They excluded the possibility that editing in 3′UTRs could affect the alternative splicing or the gene expression of targeted substrates. The authors then modeled secondary structures for potential hyper-edited substrates by predicting secondary structures for 3′UTRs of klf1, optn, and oip5 after replacing adenosine with inosine or guanosine. For both cases, the mismatches were predicted to destabilize perfect dsRNA stem loops within hyper-edited 3′UTRs so that the RNA could not form long matched dsRNA. Meanwhile, they analyzed the transcriptional profile of the Adar1E861A/E861A fetal liver and found that it was similar to those with RIG-I and MDA5 activation. Therefore, the authors hypothesized that endogenous RNA without A-to-I editing could be recognized by MDA5 and activate immune response against dsRNA (Figure 1). Moreover, they observed that MDA5 deficiency could rescue the phenotype of Adar1E861A/E861A mice. These data convincingly support that ADAR1-mediated A-to-I editing of endogenous RNAs is essential for avoiding their recognition by MDA5.

Figure 1.

ADAR1-mediated A-to-I editing of endogenous dsRNA. In the presence of ADAR1, endogenous dsRNA is edited and regarded as self dsRNA that does not initiate immunogenic MDA5 recognition. In case of ADAR1 deficiency or mutation, endogenous dsRNA is recognized by MDA5 as non-self, and then activates MAVS-dependent phosphorylation of IFN-regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) and induction of IFNs, probably leading to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases.

Findings presented in this paper illustrated an essential role of ADAR1-mediated RNA editing in prevention of immune response to endogenous dsRNA, thus providing a mechanism of how organisms distinguish self and non-self dsRNA. A recent paper published in Nature Immunology reported that the RNA helicase SKIV2L, as a component of the RNA exosome, was required for the degradation of the modified endogenous RIG-I like receptor ligands generated during the unfolded protein response via IRE1-dependent RNA decay6. The 3′-to-5′ exonuclease TREX1 and the triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 have been implicated in the control of endogenous de novo generation of DNA to avoid its recognition by DNA sensors7,8. Despite these advances in understanding the prevention of innate recognition of endogenous RNA and DNA, investigations are required for the further understanding of mechanisms used by host to discriminate endogenous versus exogenous nucleic acids.

Both RIG-I and MDA5 were identified as the major sensors of cytosolic RNA and played crucial roles in dsRNA-induced innate antiviral responses9. However, they preferred different RNA chains. Long fragments analog poly (I:C) (> 4 kb) were preferred by MDA5, whereas short fragments generated by enzyme digestion (∼300 bp) were recognized by RIG-I10. Therefore, MDA5 was suggested to sense the long dsRNA chain. However, Liddicoat et al.2 proposed that the unedited endogenous dsRNA in the 3′UTR of different transcripts (200-300 bp) may be recognized as non-self by MDA5, which is not well-fitted into the knowledge of dsRNA preference by RIG-I and MDA5. This disagreement suggests that the recognition pattern of dsRNA by RIG-I and MDA5 needs further investigations. It is also possible that the recognition pattern of endogenous dsRNA by MDA5 is different from the features characterized in exogenous dsRNA.

The role of MDA5 as a dsRNA sensor in innate immune response to self RNA is contradictory to a previous study. Mannion et al.11 observed a similar phenotype of Adar1−/− mice; however, they found that the newborn Adar1−/−Mavs−/− double mutant mice were able to feed, but they die within a day after birth. Their preliminary data suggested that the newborn Adar1−/−Mavs−/− mice still showed elevated type I IFN levels in blood. Given that MAVS is an essential adaptor utilized by both RIG-I and MDA5 to trigger type I IFN production12, apart from the MDA5-MAVS axis, there may exist MDA5-dependent but MAVS-independent mechanisms that mediate the innate immune responses in Adar1−/− or Adar1E861A/E861A mice. Moreover, since aberrant recognition of endogenous RNA and DNA usually leads to autoimmune diseases, such as the linkage between loss-of-function mutations of Trex1 gene and the Aicardi-Goutières syndrome, it may be meaningful to examine the existence of Adar1 mutation and its relation to autoimmune diseases.

In conclusion, the work by the Walkley group uncovers a new mechanism of distinguishing the self and non-self dsRNA by the immune system and opens up a new field in immune recognition research.

References

- 1Goubau D, Deddouche S, Reis e Sousa C. Immunity 2013; 38:855–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2Liddicoat BJ, Piskol R, Chalk AM, et al. Science 2015; 349:1115–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3Han L, Diao L, Yu S, et al. Cancer Cell 2015; 28:515–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4Savva YA, Rieder LE, Reenan RA. Genome Biol 2012; 13:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5Hartner JC, Walkley CR, Lu J, et al. Nat Immunol 2009; 10:109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6Eckard SC, Rice GI, Fabre A, et al. Nat Immunol 2014; 15:839–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T, et al. Cell 2008; 134: 587–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8Crow YJ. Handb Clin Neurol 2013; 113:1629–1635. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9Barbalat R, Ewald SE, Mouchess ML, et al. Annu Rev Immunol 2011; 29:185–214. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10Kato H, Takeuchi O, Mikamo-Satoh E, et al. J Exp Med 2008; 205:1601–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Young R, et al. Cell Rep 2014; 9:1482–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, et al. Nat Immunol 2005; 6:981–988. [DOI] [PubMed]