Abstract

AIM: To update our experiences with minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy for esophageal cancer.

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 445 consecutive patients who underwent minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy between January 2009 and July 2015 at the Cancer Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and used 103 patients who underwent open McKeown esophagectomy in the same period as controls. Among 375 patients who underwent total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy, 180 in the early period were chosen for the study of learning curve of total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy. These 180 minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomies performed by five surgeons were divided into three groups according to time sequence as group 1 (n = 60), group 2 (n = 60) and group 3 (n = 60).

RESULTS: Patients who underwent total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy had significantly less intraoperative blood loss than patients who underwent hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy or open McKeown esophagectomy (100 mL vs 300 mL vs 200 mL, P = 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in operation time, number of harvested lymph nodes, or postoperative morbidity including incidence of pulmonary complication and anastomotic leak between total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy, hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and open McKeown esophagectomy groups. There were no significant differences in 5-year survival between these three groups (60.5% vs 47.9% vs 35.6%, P = 0.735). Patients in group 1 had significantly longer duration of operation than those in groups 2 and 3. There were no significant differences in intraoperative blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, or postoperative morbidity including incidence of pulmonary complication and anastomotic leak between groups 1, 2 and 3.

CONCLUSION: Total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy was associated with reduced intraoperative blood loss and comparable short term and long term survival compared with hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy or open Mckeown esophagectomy. At least 12 cases are needed to master total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy in a high volume center.

Keywords: Surgical procedures, Minimally invasive, Esophagectomy, Outcome, Learning curve

Core tip: Total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy had reduced intraoperative blood loss and comparable short term and long term survival compared with hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy or open Mckeown esophagectomy. At least 12 cases are needed to master total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy in a high volume cancer center.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer is a growing concern and is the eighth most common cancer worldwide[1]. According to statistics of esophageal cancer in China, the incidence and death rates were 22.14 per 100000 person-years and 16.77 per 100000 person-years in 2009, respectively, being the top one in the world[2]. For resectable carcinoma of the esophagus, surgery remains the gold standard of treatment. Minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) was introduced into clinical practice in 1992 in order to minimize the surgical injury reaction and reduce the morbidity and mortality rates of esophagectomy[3]. However, concerns existed for whether MIE may reduce systematic inflammatory response syndrome and provide comparable oncologic clearance with open esophagectomy even 5 years ago[4].

In the past 5 years, several studies including one randomized controlled trial reported reduced postoperative pulmonary complication rates, comparable oncologic clearance and similar long term survival between MIE and open esophagectomy[5-14]. Our previous study demonstrated reduced morbidity rate and comparable oncologic clearance in minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy group compared with open McKeown esophagectomy[9]. We started minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy in 2009. Here, we will review these minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomies and focus on short term outcome, long term survival and learning curve of minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General information

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Science. The medical records of 445 consecutive patients who underwent minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy between January 2009 and July 2015 at the Cancer Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences were retrospectively reviewed. In the same period, 103 patients received open McKeown esophagectomy. The clinical variables of the paired groups were compared, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), neoadjuvant therapy, tumor location, duration of operation, intraoperative blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, differentiation, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, morbidity rate, rate of anatomic leakage, pulmonary morbidity rate, mortality rate and length of hospital stay. Esophageal cancer staging was carried out according to the AJCC 2009 cancer staging system[15]. All involved patients gave their informed consent prior to study inclusion. A randomized, controlled trial of neoadjuvant treatment has shown a survival benefit in locally advanced esophageal carcinoma as compared with esophagectomy alone in 2012[16]. Since then, we adopted chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy as an alternative for locally advanced esophageal cancer.

Surgical technique

MIE includes total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy[8]. The former consists of thoracoscopic esophagectomy, laparoscopic gastric preparation and gastroesophageal cervical anastomosis, while there are thoracoscopic esophagectomy plus open gastric preparation or laparoscopic gastric preparation plus open esophagectomy in the hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy group. Since 2009, total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy has been introduced and in use. The selection criteria for patients to either total MIE, hybrid MIE or open esophagectomy were mainly based on the clinical stage and the experiences of surgeons. Patients with early stage esophageal cancer received more minimally invasive esophagectomies than open esophagectomies, and surgeons who received training in minimally invasive thoracic surgery more performed minimally invasive esophagectomies than open esophagectomies.

Minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy

Thoracoscopic phase: The patient was placed in the left lateral decubitus position. The position of the double-lumen tube was verified, and single-lung ventilation was used. Four thoracoscopic ports were established. A 10 mm port was placed at the seventh intercostal space, just along the anterior axillary line, for the camera. Another 10 mm port was placed at the eighth or ninth intercostal space, posterior to the axillary line, for the dissection instrument (ultrasonic coagulating shears) and passage of the end-to-end circular stapler (EEA; Covidien or Johnson) or Hem-lock. A 5 mm port was placed in the anterior axillary line, at the third or fourth intercostal space, and this was used to pass a fan-shaped retractor to retract the lung anteriorly and allow exposure of the esophagus. A 5 mm port was placed just below the subscapular tip to place the instruments for retraction and counter traction. The inferior pulmonary ligament was divided. The mediastinal pleura overlying the esophagus was divided and opened to the level of the azygous vein to expose the thoracic esophagus. The azygous vein was then dissected and divided with an endoscopic vascular stapler or Hem-lock. The thoracic esophagus, alone with the periesophageal tissue and mediastinal lymph nodes, was circumferentially mobilized from the diaphragm to the level of inlet of the thorax. Mediastinal lymphadenectomy was done for every patient, and the resected lymph nodes included left recurrent and right subclavian,paratracheal, subcarinal, left and right bronchial, lower posterior mediastinum, para-aortic, and para-oesophageal lymph nodes. The chest was inspected closely, and hemostasis was verified. Chest tube was routinely placed.

Laparoscopic phase: The patient was placed in a supine position. A pneumoperitoneum (12-14 cm H2O) was established by CO2 injection through an umbilical port. A total of five abdominal ports (three 5 mm and two 10 mm) were used. After placement of the ports, the first step of the laparoscopic phase was an exploration of the abdomen to rule out advanced disease. The mobilization of the stomach was started with the division of the greater curvature using a Harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, OH, United States). The short gastric vessels were then divided. The gastrocolic omentum was then divided, with care taken to preserve the right gastroepiploic artery. The posterior attachments of the stomach were then divided after retraction of the stomach anteriorly. The left gastric vessel was divided at its origin from the celiac trunk with an endoscopic gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler or Hem-lock. Lymphatic tissues around vessels were included in the resection. Subsequently, the right crus was visualized and dissected, followed by dissecting and defining the left crura of the diaphragm. The abdominal/distal esophagus was dissected as far as possible toward the distal end. The gastric conduit was made extracorporeally. Pyloroplasty or gastric drainage procedure was not routinely performed in our study. We inserted duodenal nutrition tube before anastomosis in the operation. The abdomen was inspected to make sure that hemostasis was adequate and the incisions were closed.

Cervical anastomosis: After laparoscopic phase and thoracoscopic phase, a 4 to 6 cm horizontal neck incision was made to expose the cervical esophagus. Careful dissection was performed down until the thoracic dissection plane was encountered, generally quite easily since the VATS dissection was continued well into the thoracic inlet. The esophagogastric specimen was pulled out of the neck incision and the cervical esophagus divided high. The specimen was removed from the field. An anastomosis was performed between the cervical esophagus and gastric tube using standard techniques (mechanical stapled or handsewn anastomosis in an end-to-side fashion).

Open Mckeown esophagectomy: The first stage was started with a right posterolateral thoracotomy. The mediastinal pleura overlying the esophagus were divided with electrotome. The thoracic esophagus, alone with the periesophageal tissue and mediastinal lymph nodes, was circumferentially mobilized from the diaphragm to the level of the inlet of the thorax.

The second stage is the mobilization of the stomach which was started with the division of the greater curvature using ultrasonic coagulating shears. The short gastric vessels were divided with ultrasonic coagulating shears as well. The gastrocolic omentum was then divided, with care taken to preserve the right gastroepiploic artery. The posterior attachments of the stomach were then divided after retraction of the stomach anteriorly. The left gastric vessel was divided at its origin from the celiac trunk with sutures. Lymphatic tissues around vessels were included in the resection. Subsequently, the abdominal esophagus was dissected as far as possible toward the distal end. Pyloroplasty was not routinely performed. The abdomen is inspected to make sure that hemostasis was adequate and the incisions were closed. For the last stage, the cervical incision was made and then anastomosis was performed like minimally invasive esophagectomy.

Postoperative care: The patients were placed in an intensive care unit or discharged to ward directly from operation room according to the judgement of anesthetist. Assessment of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury was done on the 1st d postoperatively. Postoperative respiratory tract management included chest physiotherapy and early ambulation. Patient-controlled analgesia was given to every patient to control postoperative pain.

Learning curve of total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy

In order to study the learning curve of total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy, we selected data of 180 patients who underwent total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy in the early period which was performed by five senior thoracic oncologic surgeons who majored in thoracic surgical oncology over 20 years. All 180 patients were divided into three groups according to time sequence from January 2009 to August 2013 as group 1 (n = 60), from September 2013 to November 2013 as group 2 (n = 60) and from December 2013 to group 3 (n = 60).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software package 16.0 for Windows was used for statistical analyses. Data are presented as median value (interquartile range) for continuous variables, and percentages for dichotomous variables. Continuous variables were analyzed using ANOVA test or nonparametric test, and categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher exact test. Survival was estimated using Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank tests were used to analyze differences between curves. The significant level was set as a P value less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics

From January 2009 to June 2015, 445 cases of minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy were conducted at our hospital. In this cohort, the median age was 60 years (range, 36-79 years) and there were 341 males and 104 females. Twenty-one patients underwent neoadjuvant radiotherapy, and 30 patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Other clinical variables are displayed in Table 1. Five patients were converted into open thoracotomy and laparotomy and the reasons for conversion are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients receiving minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy n (%)

| Clinical variable | Value |

| Age (yr) | 60 (36-79) |

| Male gender | 341 (76.6) |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 21 (4.7) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 30 (6.7) |

| Location | |

| Upper | 96 (21.6) |

| Middle | 292 (65.6) |

| Lower | 57 (12.8) |

| Type of surgery | |

| Total MIME | 375 (84.3) |

| Hybrid MIME | 70 (15.7) |

MIME: Minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy.

Table 2.

Reasons for conversion of patients receiving minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy

| Reason | Number |

| Rupture of trachea | 1 |

| Pleural adhesion | 2 |

| Adhesion of abdominal cavity | 2 |

The cohort was divided into three groups based on operative technique used. Of 548 McKeown esophagectomies, there were 375 total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomies, 70 hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomies and 103 open McKeown esophagectomies. The selection of which approach was based on the opinion of surgeons. Patients who underwent minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy were older than patients who underwent open Mckeown esophagectomy. Patients who underwent open McKeown esophagectomy were more in the proximal third of the esophagus and more received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Table 3) .

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients receiving McKeown esophagectomy n (%)

| Clinical variable | Total MIME (n = 375) | Hybrid MIME (n = 70) | Open McKeown esophagectomy (n = 103) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 59 (54-65) | 62 (55-67) | 56 (52-63) | 0.024 |

| Sex (Male) | 289 (77.1) | 52 (74.3) | 84 (81.6) | 0.490 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23 (21-25) | 22 (20-25) | 23 (20-24) | 0.100 |

| Tumor location | < 0.001 | |||

| Upper | 78 (20.8) | 18 (25.7) | 58 (56.3) | |

| Middle | 248 (66.1) | 44 (62.9) | 39 (37.9) | |

| Lower | 49 (13.1) | 8 (11.4) | 6 (5.8) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 21 (5.6) | 9 (12.9) | 11 (10.7) | 0.042 |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 16 (4.3) | 5 (7.1) | 11 (10.7) | 0.043 |

MIME: Minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy; BMI: Body mass index; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Perioperative outcomes of patients undergoing three types of Mckeown esophagectomy

As shown in Table 4, patients who underwent total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy had significantly less intraoperative blood loss than patients who underwent hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and open McKeown esophagectomy. However, there were no significant differences in duration of operation, number of harvested lymph nodes, or postoperative morbidity including incidence of pulmonary complication and anastomotic leak between total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy, hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and open McKeown esophagectomy groups.

Table 4.

Perioperative outcomes of patients receiving Mckeown esphagectomy n (%)

| Clinical variable | Total MIME (n = 375) | Hybrid MIME (n = 70) | Open McKeown esophagectomy (n = 103) | P value |

| Duration of operation (min) | 330 (270-420) | 370 (305-435) | 340 (320-400) | 0.323 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 100 (100-200) | 300 (100-300) | 200 (100-300) | 0.001 |

| Number of harvested lymph nodes | 22 (16-31) | 19 (14-29) | 25 (19-32) | 0.293 |

| AJCC staging | 0.085 | |||

| 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | |

| I | 108 (28.8) | 19 (27.1) | 17 (16.5) | |

| II | 172 (45.9) | 33 (47.1) | 49 (47.6) | |

| III | 94 (25.1) | 17 (24.3) | 37 (35.9) | |

| Differentiation | 0.685 | |||

| High | 107 (28.6) | 18 (25.7) | 35 (34.0) | |

| Middle | 209 (55.9) | 40 (57.1) | 50 (48.5) | |

| Low | 58 (15.5) | 12 (17.1) | 18 (17.5) | |

| Complete resection | 374 (99.7) | 70 (100) | 103 (100) | 0.794 |

| Overall Morbidity | 73 (19.5) | 13 (18.6) | 22 (21.6) | 0.864 |

| Pulmonary complications | 11 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | 6 (5.8) | 0.347 |

| Leakage | 46 (12.3) | 10 (14.3) | 9 (8.7) | 0.493 |

| In-hospital mortality | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1.0 (0) | 0.696 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 16 (14-24) | 18 (16-27) | 21 (16-28) | 0.078 |

MIME: Minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

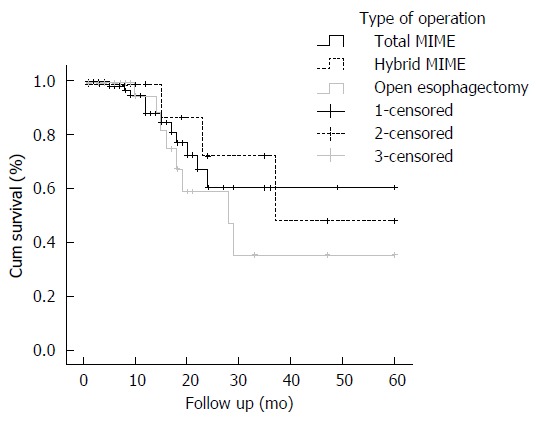

Survival

Kaplan-Meier plots depict the long term survival of patients who underwent three types of operation: total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy, hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and open McKeown esophagectomy (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in 5-year survival between these three types (60.3% vs 47.9% vs 35.3%, P = 0.579).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of three types of operation. There were no significant differences in 5-yr survival between total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy, hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and open Mckeown esophagectomy (60.3% vs 47.9% vs 35.3%, P = 0.579). MIME: Minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy.

Learning curve of total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy

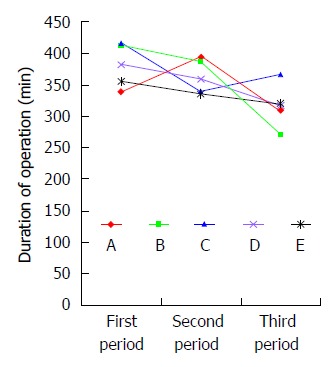

Patients in group 1 (n = 60) had significantly longer duration of operation than those in groups 2 (n = 60) and 3 (n = 60). There were no significant differences in intraoperative blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, or postoperative morbidity including incidence of pulmonary complication and anastomotic leak between groups 1, 2 and 3 (Table 5). Five surgeons performed 180 total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomies. There were no significant differences in the short term outcomes or oncologic clearance between these three groups. The duration of operation got steady after the first 60 cases for 5 surgeons, suggesting that 12 cases were needed for a senior surgeon to master total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy at our hospital, a high volume cancer center. Then we analyzed the learning curve for each of 5 surgeons and found that all surgeons had a trend of reduction of duration of operation. Of 5 surgeons, there were significant differences in duration of operation between surgeons A and B, while there were no significant differences in duration of operation between surgeons C, D and E (Figure 2).

Table 5.

Comparison of perioperative outcomes of patients who underwent total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy in the early period n (%)

| Clinical variable | Group 1 (n = 60) | Group 2 (n = 60) | Group 3 (n = 60) | P value |

| Duration of operation (min) | 350 (285-450) | 303 (270-373) | 300 (240-370) | 0.004 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 300 (125-375) | 200 (100-300) | 100 (100-300) | 0.081 |

| Number of harvested lymph nodes | 21 (17-30) | 22 (16-31) | 21 (16-26) | 0.866 |

| Overall morbidity | 10 (16.7) | 13 (21.7) | 14 (23.3) | 0.643 |

| Pulmonary morbidity | 2 (3.3) | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 0.237 |

| Leakage | 5 (8.3) | 7 (11.7) | 11 (18.3) | 0.248 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.366 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 17 (14-22) | 20 (14-31) | 15 (12-21) | 0.335 |

Figure 2.

Learning curve of total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy of five surgeons. Durations of operation for five surgeons in three periods are as follows: surgeon A (340 ± 57 min vs 395 ± 105 min vs 310 ± 61 min, P = 0.037); surgeon B (413 ± 109 min vs 387 ± 110 min vs 272 ± 58 min, P = 0.002); surgeon C (418 ± 65 min vs 339 ± 116 min vs 367 ± 74 min, P = 0.098); surgeon D (383 ± 105 min vs 359 ± 82 min vs 317 ± 116 min, P = 0.287); and surgeon E (355 ± 123 min vs 337 ± 77 min vs 320 ± 159 min, P = 0.789).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that patients who underwent total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy had similar short term outcome and long term survival compared with patients who underwent hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy or open Mckeown esophagectomy.

The feasibility of MIE has been well established in our center as previously reported[9]. Recently, a meta-analysis involving 13267 patients demonstrated reduced in-hospital mortality in patients who underwent MIE compared with patients who underwent open esophagectomy[14]. In that study, the mortality rates were 3.0% and 4.6% in MIE and open esophagectomy group, respectively[14]. Also, a significant effect of MIE was observed in that study in reducing the risk of pulmonary complications compared with open esophagectomy (17.8% vs 20.4%)[14]. We did not observe any reduction of incidence of morbidity or mortality in MIE group compared with open esophagectomy group. However, there was a trend in our study that the rate of pulmonary complication decreased in total minimally invasive group and hybrid minimally invasive group compared with open group, with the pulmonary complication rates of 2.9%, 2.9% and 5.8%, respectively. Relatively small number of samples in our study may account for the reason. There was no significant difference in the rate of anastomotic leak after esophagectomy between MIE and open esophagectomy group in our study, which is consistent with the result of the meta-analysis[14].

The results of a large randomized, controlled trial of neoadjuvant treatment demonstrated a survival benefit in locally advanced esophageal carcinoma as compared with esophagectomy alone, with a five-year survival of 47% in neoadjuvant treatment group compared with 34% in the surgery group[16]. And since then, some surgeons at our hospital adopted neoadjuvant treatment as an alternative for locally advanced esophageal carcinoma to surgery alone. The rate of neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced esophageal carcinoma was only 20% at our hospital. A low fraction of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the study of van Hagen et al[16] (around 20%) may preclude the application of neoadjuvant treatment at our hospital. Several meta-analyses demonstrated consistent results of survival advantage of neoadjuvant treatment plus surgery over surgery alone for resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma[17-21]. However, there were limited data regarding the survival advantage of neoadjuvant treatment plus surgery over surgery alone for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. More studies of neoadjuvant treatment on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma are needed to define the role of neoadjuvant treatment in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

We found a similar oncologic clearance rate as demonstrated by no difference in number of dissected lymph nodes between MIE and open esophagectomy group. And we found similar 5-year survival between MIE and open esophagectomy group. Recently, a propensity score-matched comparison study showed similar lymph node harvest and equal oncologic survival in MIE and open esophagectomy group which are similar to our results[11]. Two recent studies showed better long term survival in MIE group compared with open esophagectomy group, and select bias may lead to the results[12,13]. In these two studies, more early tumors were selected in MIE group and more advanced cancers in open esophagectomy group[12,13]. More studies are needed to clarify the survival advantage of MIE over open esophagectomy.

Many surgeons reported less intraoperative blood loss in MIE group than in open esophagectomy group[12,13,22]. In this study, we observed a similar result. It is reported that perioperative blood transfusion was a negative prognostic factor for long-term survival in esophageal cancer after esophagectomy. Therefore, less intraoperative bleeding may lessen the need for perioperative transfusion, which may increase long term survival of patients who received MIE[23].

Apart from perioperative morbidity and long term survival, other measures including quality of life questionnaires such as European Organization for Research on Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) and QLQ-0ES18 and cost analysis were used to assess the difference between minimally invasive and open esophagectomies[24,25]. More importantly, quality of life measures could be a tool to provide clinical information from patients’ perspective suggesting cancer recurrence[26]. Indeed, an ongoing multicenter prospective study organized and led by our hospital are being performed to compare the effects between minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and open McKeown esophagectomy in China[27]. The measures included perioperative morbidity, mortality and long term survival. Also, quality of life questionnaires (EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-0ES18) are included in this ongoing study. Owing to the retrospective nature of this study, we did not include the quality of life questionnaires in the analysis. Reduced cost of minimally invasive esophagectomy compared with open esophagectomy has been demonstrated in our early study[9]. Therefore, minimally invasive esophagectomy had the advantages of decreased intraoperative blood and reduced cost compared with open esophagectomy, with comparable perioperative morbidity and mortality, and long term survival. Although minimally invasive esophagectomy is technically changing, it is a valuable procedure for the surgical treatment of esophageal cancer patients in specialized centers[28].

Learning curve of a new technique is an important issue in clinical practice, which may influence the outcome of patients and training of the surgeons. The risk of increased technical problems when applying a new procedure is not uncommon[29]. As Tao reported that minimally invasive approaches were demonstrated to decrease the risk of functional complications including arrhythmia, pulmonary infection, acute lung injury (ALI), ileus, acute renal failure or acute hepatic failure but not technical problems including perioperative bleeding, chylothorax, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (RLNP), and anastomotic leakage. In their study, functional complications between open esophagectomy and MIE group were 32.0% and 1.79%, respectively, while technical complications were 12.0% and 23.9%, respectively[29]. In our study, there was no significant difference in technical problems including anastomotic leak between patients who underwent total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy, hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and open McKeown esophagectomy. However, the duration of operation decreased significantly in groups 2 and 3 than in group 1, suggesting that increment of number of procedures would improve the surgeon’s performance. Also, there was a trend that intraoperative blood loss decreased as the surgeon’s experiences increased. However, there were no significant differences in the number of harvested lymph nodes or postoperative morbidity including incidence of pulmonary complication and anastomotic leak between groups 1, 2 and 3. Therefore, a new MIE program can be implemented safely with comparable oncologic clearance rate and postoperative morbidity rate after approximately 12 cases for a surgeon at a high volume cancer center. Lin et al[30] reported that surgery skill can be reached after 40 cases. In their study, an attending doctor who performed 40 cases may reach the plateau of learning curve. However, in our study, senior doctors with over 20 years of experiences with thoracic surgery who performed only 12 cases can overcome the skill obstacle.

The limitation of this study mainly comes from its retrospective nature, which carries a risk of selection bias. For example, there were more patients who had the tumor in the upper third of the esophagus in open esophagectomy group. Second, the patients were from one hospital, which may not be generalized in other medical centers. Last, rates of local and distant recurrences, and long term survival analysis are needed to determine the oncologic clearance apart from the comparison of number of harvested lymph nodes.

In conclusion, total minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy had reduced intraoperative blood loss and comparable short term and long term survival compared with hybrid minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy or open Mckeown esophagectomy. At least 12 cases are needed to master the technique in a high volume cancer center.

COMMENTS

Background

Open McKeown esophagectomy is a complex surgery for upper third esophageal cancer with higher morbidity rate than open Ivor Lewis and Sweet esophagectomy. Minimally invasive esophagectomy is a new technique which aims to reduce systematic inflammatory response syndrome and perioperative morbidity rate.

Research frontiers

In the past 5 years, several studies including one randomized controlled trial reported reduced postoperative pulmonary complication rates, comparable oncologic clearance and similar long term survival. However, few studies focused on the comparison of open McKeown esophagectomy and minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study again reinforced the feasibility of minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy and extended previous study of learning curve of minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy that at least 12 cased are needed to reach the plateau of this technique.

Applications

The results of this study may provide new data for thoracic surgeons who majored in esophageal surgery that minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy is feasible and is associated with less intraoperative blood loss. Most importantly, performing 12 cases of minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomies may reach the plateau of this technique.

Peer-review

This manuscript compared totally minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE), hybrid MIE and open three stage (McKeowm) oesophagectomy. The authors found the procedure ontologically safe in terms of lymph node yield and long term survival and technically safe in terms of blood loss, operating time, morbidity and mortality. This is an interesting manuscript and clearly written and organized.

Footnotes

Supported by The Fund of Capital Health Technology Development Priorities Research Project, No. 2014-1-4021.

Institutional review board statement: Institutional Review Board of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Science reviewed and approved this study.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was given by patients preoperatively. All included patients accepted the possibility to collect their patient data.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: September 15, 2015

First decision: October 22, 2015

Article in press: November 9, 2015

P- Reviewer: Merrett ND, Shimi SM S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Li G, Wu L, He J. Report of incidence and mortality in China cancer registries, 2009. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:10–21. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2012.12.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuschieri A, Shimi S, Banting S. Endoscopic oesophagectomy through a right thoracoscopic approach. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1992;37:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbella FA, Patti MG. Minimally invasive esophagectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3811–3815. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i30.3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nafteux P, Moons J, Coosemans W, Decaluwé H, Decker G, De Leyn P, Van Raemdonck D, Lerut T. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy: a valuable alternative to open oesophagectomy for the treatment of early oesophageal and gastro-oesophageal junction carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1455–1463; discussion 1463-1464. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsujimoto H, Takahata R, Nomura S, Yaguchi Y, Kumano I, Matsumoto Y, Yoshida K, Horiguchi H, Hiraki S, Ono S, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for esophageal cancer attenuates postoperative systemic responses and pulmonary complications. Surgery. 2012;151:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, Bonavina L, Rosman C, Garcia JR, Gisbertz SS, Klinkenbijl JH, Hollmann MW, de Lange ES, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1887–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mu JW, Chen GY, Sun KL, Wang DW, Zhang BH, Li N, Lv F, Mao YS, Xue Q, Gao SG, et al. Application of video-assisted thoracic surgery in the standard operation for thoracic tumors. Cancer Biol Med. 2013;10:28–35. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mu J, Yuan Z, Zhang B, Li N, Lyu F, Mao Y, Xue Q, Gao S, Zhao J, Wang D, et al. Comparative study of minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer in a single cancer center. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:747–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J, Lyu B, Zhu W, Chen J, He J, Tang S. A retrospective cohort comparison of esophageal carcinoma between thoracoscopic and laparoscopic esophagectomy and open esophagectomy. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;53:378–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Shen Y, Feng M, Zhang Y, Jiang W, Xu S, Tan L, Wang Q. Outcomes, quality of life, and survival after esophagectomy for squamous cell carcinoma: A propensity score-matched comparison of operative approaches. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:1006–1014; discussion 1014-1015.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palazzo F, Rosato EL, Chaudhary A, Evans NR, Sendecki JA, Keith S, Chojnacki KA, Yeo CJ, Berger AC. Minimally invasive esophagectomy provides significant survival advantage compared with open or hybrid esophagectomy for patients with cancers of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burdall OC, Boddy AP, Fullick J, Blazeby J, Krysztopik R, Streets C, Hollowood A, Barham CP, Titcomb D. A comparative study of survival after minimally invasive and open oesophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3694-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou C, Zhang L, Wang H, Ma X, Shi B, Chen W, He J, Wang K, Liu P, Ren Y. Superiority of Minimally Invasive Oesophagectomy in Reducing In-Hospital Mortality of Patients with Resectable Oesophageal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW. 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1721–1724. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, Richel DJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Hospers GA, Bonenkamp JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F, Wang YM, He W, Li XK, Peng FH, Yang XL, Fan QX. Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery could improve the efficacy of treatments in patients with resectable esophageal carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:3138–3145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronellenfitsch U, Schwarzbach M, Hofheinz R, Kienle P, Kieser M, Slanger TE, Burmeister B, Kelsen D, Niedzwiecki D, Schuhmacher C, et al. Preoperative chemo(radio)therapy versus primary surgery for gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: systematic review with meta-analysis combining individual patient and aggregate data. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3149–3158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumagai K, Rouvelas I, Tsai JA, Mariosa D, Klevebro F, Lindblad M, Ye W, Lundell L, Nilsson M. Meta-analysis of postoperative morbidity and perioperative mortality in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal and gastro-oesophageal junctional cancers. Br J Surg. 2014;101:321–338. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng J, Wang C, Xiang M, Liu F, Liu Y, Zhao K. Meta-analysis of postoperative efficacy in patients receiving chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for resectable esophageal carcinoma. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:151. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumagai K, Rouvelas I, Tsai JA, Mariosa D, Lind PA, Lindblad M, Ye W, Lundell L, Schuhmacher C, Mauer M, et al. Survival benefit and additional value of preoperative chemoradiotherapy in resectable gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction cancer: a direct and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubo N, Ohira M, Yamashita Y, Sakurai K, Toyokawa T, Tanaka H, Muguruma K, Shibutani M, Yamazoe S, Kimura K, et al. The impact of combined thoracoscopic and laparoscopic surgery on pulmonary complications after radical esophagectomy in patients with resectable esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:2399–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kakuta T, Kosugi S, Kanda T, Ishikawa T, Hanyu T, Suzuki T, Wakai T. Prognostic factors and causes of death in patients cured of esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1749–1755. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scarpa M, Valente S, Alfieri R, Cagol M, Diamantis G, Ancona E, Castoro C. Systematic review of health-related quality of life after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4660–4674. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ecker BL, Savulionyte GE, Datta J, Dumon KR, Kucharczuk J, Williams NN, Dempsey DT. Laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy improves hospital outcomes and reduces cost: a single-institution analysis of laparoscopic-assisted and open techniques. Surg Endosc. 2015:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang YL, Tsai YF, Chao YK, Wu MY. Quality-of-life measures as predictors of post-esophagectomy survival of patients with esophageal cancer. Qual Life Res. 2015:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ClinicalTrials.gov Web site. Traditional three incisions vs minimally invasive thoracol-laparoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Accessed February 3, 2015. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02355249.

- 28.Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2499–2509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1314530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao T, Fang W, Gu Z, Guo X, Ji C, Chen W. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:303–306. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J, Kang M, Chen C, Lin R, Zheng W, Zhug Y, Deng F, Chen S. Thoracolaparoscopy oesophagectomy and extensive two-field lymphadenectomy for oesophageal cancer: introduction and teaching of a new technique in a high-volume centre. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:115–121. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]