Abstract

Laser microdissection (LMD) was utilized for the separation of the yolk, follicular wall and surrounding stromal cells of small white follicles (SWF) obtained from reproductively active domestic fowl. Herein, we provide an in-situ proteomics based approach to studying follicular development through the use of LMD and mass spectrometry. This study resulted in a total of 2,889 proteins identified from the three specific isolated compartments. White yolk from the smallest avian follicles resulted in the identification of 1,984 proteins, while isolated follicular wall and ovarian stroma yielded 2,470 and 2,456 proteins, respectively. GO annotations highlighted the functional differences between the compartments. Among the three compartments examined, the relative abundance of vitellogenins, steroidogenic enzymes, anti-Mullerian hormone, transcription factors, and proteins involved in retinoic acid receptors/retinoic acid synthesis, transcription factors and cell surface receptors such as EGFR and their associated signaling pathways reflected known cellular function of the ovary. This study has provided a global proteome for SWF, white yolk and ovarian stroma of the avian ovary that can be used as a baseline for future studies and verifies that the coupling of LMD with proteomic analysis can be used to evaluate proteins from small, physiologically functional compartments of complex tissue.

Introduction

The avian ovary is unique among vertebrates in that it contains hundreds of follicles but has about 5 large yolky follicles arranged in a hierarchy based upon size from about 9 mm to 40 mm in diameter. The largest follicle is designated as the F1 follicle which is the most mature and is destined for the next ovulation. A reproductively active domestic hen ovulates roughly every day, and an active ovary generally contains a succession of preovulatory follicles (F2–F5) that mature to the next size to take the place of the newly released F1 follicle. A new F5 follicle is recruited from a pool of 7–9 small yellow follicles (SYF) that range 5 – 9 mm in diameter. Below SYF lies a pool of large white follicles (LWF) 2–5 mm in size that contain no apparent yellow yolk. The smallest and most immature of the avian ovarian follicles are the numerous small white follicles (SWF) that are less than 2 mm in diameter. Maturation of avian ovarian follicles has largely focused upon the process of recruitment from the SYF to the preovulatory follicles and the maturation of the F1. Much of this has centered on changes in steroidogenesis associated with the transition from SYF and maturation of the F1 follicle. Granulosa cells and theca cells of the follicular wall are the main sources for the production of steroid hormones.1–3 Two hypotheses exist to explain the interplay between the two cell types for the production of steroids. The first suggests that the granulosa cells of preovulatory follicles produce progestins that are, in turn, used as a substrate by the theca cells for the production of androgen and estrogen.1 The other proposes that theca cells can synthesize progestins, androgen, and estrogen independently of granulosa cells.4 A key component to the steroidogenic pathway is the synthesis of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR). Recently, it has been shown that prehierarchal follicles (6–8 mm) fail to express mRNA of the StAR protein.5, 6 However, it is not well understood how these steroidogenic pathways function in the small white follicles.

Very little research has been done to understand the biology of the smallest follicles of the avian ovary and most work has consisted in removing the follicles from the stroma of the ovary for the culture of whole follicles. We wished to gain access to the smallest follicles; and, if possible, apply global proteomics to the various ovarian compartments. To this end, laser microdissection (LMD) was used to isolate the following specific compartments: follicular wall (granulosa/theca cells), white yolk, and ovarian stromal tissue. A global proteome profile of each compartment was generated and analyzed using LC-MS/MS. In the process we were able to identify 2,889 total proteins among the three compartments. In addition, this is the first report of the identification of 1,984 proteins specifically from the white yolk of SWF. Furthermore, the approach described can be utilized to examine a relative abundance of proteins in various compartments of structurally complex tissues.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care and Biospecimen collection

Animals were obtained from a flock of 22 month old healthy Bovan’s White commercial laying hens. The flock was managed in accordance with the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Guide with all the husbandry practices being approved by and under the oversight of North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Birds were housed in individual cages under 16L:8D photoperiod and fed an 18% protein layer diet. The health and egg-laying status of the birds were monitored daily and only reproductively active hens were chosen for the study.

Ovaries were removed and cleaned with phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.0. All large yolky follicles and small yellow follicles were removed. In some cases a few large white follicles were also removed to reduce the size of the tissue sample. In addition, samples of liver tissue were obtained to test all proteomic procedures and to determine the number of cells needed to maximize protein detection. Each tissue was placed into cryomold holders (Miles Inc., Elkhart, IN) and frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo, IL). Briefly, each mold was placed into an isopentane (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) bath surrounded by liquid nitrogen. Once frozen, serial slices of 10 µm thick pieces were cut using a CM1950 cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo, IL). Sections used for LMD were placed onto polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) membrane slides (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo, IL). Sections used for hemotoxylin and eosin staining were placed onto standard microscope slides (VWR, Radnor, PA).

Optimization of Protein Identification

In order to determine the appropriate amount of tissue to be excised for proteomic analysis, it was necessary to examine the relationship between the tissue area captured and the yield of identified proteins. Using the chicken liver samples, varying amounts of tissue were excised using laser capture microscopy (LCM) based on area and each portion was individually examined for the total amount of protein detected. The smallest sampled area analyzed was approximated 48,500 µm2 which resulted in 12 identified proteins, while 2,480 proteins were identified in an area of 4.6-E7 µm2 removed. With increasing sample area, the number of proteins identified increased to a maximum but reached a plateau where the amount of sample did not contribute to additional protein detection; Figure S1 (supplementary information)). This plateau indicated that the LC-MS/MS system was undersampling the proteome. In the subsequent experiments used for identifying the proteins in individual compartments of the ovary, an area of 8-E6 µm2 was chosen to maximize the amount of proteins identified in the minimal amount of tissue needed for analysis.

Determination of Follicular Diameter

In order to predict the follicular diameter of the small white follicles in tissue sections, ovarian tissue was cut into several 10 µm serial sections. The first 4 sections were placed on plain glass slides. The next 2 serial tissue sections were placed on PEN membrane slides for LMD analysis. Subsequently, the first 4 sections were fixed and hemotoxylin-eosin (H&E) stained. The H&E stained slides were then observed using the LMD system and the diameters of all the follicles within each section were recorded. The true diameters of the three dimensional follicles were then derived using a minimum of a two-point best fit curve for a circle algorithm using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Nine follicles follicles between 1.6 and 0.3 mm in size were chosen for proteomic analysis using the two remaining serial sections on the corresponding PEN membrane slides.

Laser Capture Microdissection

Each polyethene napthalate (PEN) membrane slide was prepared individually for laser microdissection. Each slide was rinsed with 100% ethanol (Anhydrous KOPTEC USP, VWR, Randor PA) for 2 minutes followed by 1 minute rinses in 95% and 75% ethanol. Then, the slide was placed in nuclease free distilled water (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) for 30 sections. After removing the water, 100 µL of Paradise®Plus staining solution (Molecular Devices) was used to cover the entire section for approximately 30 seconds. The excess stain was gently removed from the slide prior to washing with 75% then 95% ethanol for 30 seconds each. An additional wash was performed in 100% ethanol for 1 minute. The slide was then placed into xylene (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for approximately 5 minutes for complete dehydration of the tissue section.

Samples were excised utilizing a laser microdissection (LMD 7000, Leica Microsystems) from 9 follicles between 270 µm to 1600 µm in diameter as calculated above and divided into white yolk, follicular wall, and ovarian stromal tissue. To gain a true representation of white yolk, samples were chosen from follicle sections that did not exhibit any nuclear material. A fourth sample consisting of random regions of the ovary were also sampled. Proteins samples were extracted using lysis buffer consisting of 30 µL of 100 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 4% SDS. The solution was then heated at 95 °C for 5 minutes. For separation of the intact PEN membrane from the solubilized protein, the samples were then centrifuged for 20 min at 14,000 g.

Filter Aided Sample Preparation for Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy

The samples were digested using a modified filter aided sample preparation (FASP) method7, 8 with minor changes. Briefly, the disulfide bonds were reduced by adding 3 µL of 50 mM DTT to each sample and incubated for 30 min at 56 °C. The sample was then mixed with 200 µL of 8 M urea solution which was made with 100 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0. The solution was then transferred onto a Vivacon 500 30 kDa molecular weight (MW) cutoff filter (Vivacon Products, Littleton, MA). To prevent carbamylation caused by the presence of urea, a refrigerated centrifuge (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) was used and the samples were centrifuged for 15 min. at 21 °C. Another wash of 200 µL of 100 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0 was repeated and the flow through was then discarded. The alkylation step was accomplished when 100 µL of 50 mM iodoacetamide was added and incubated for 20 min in the dark at room temperature. Wash steps then ensued with 100 µL 8 M urea and 100 µL of 100 mM Tris HCl pH 7.0 with each wash repeated 3 times. At each step the filters were centrifuged for 10 min. at 14,000 g. Trypsin digestion occurred when a total of 0.25 µg of trypsin in 40 µL of 100 mM Tris HCl pH 7.0 was added onto the filter. Allowing for 16 hours of digestion at 37 °C, the peptides were eluted through the filter by centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 g. An additional 40 µL of 100 mM Tris HCl pH 7.0 was added and then spun down for 10 min at 14,000 g. The sample was then reduced to dryness.

Nano-LC-MS/MS

An Easy nLC II (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) was coupled to a quadrupole-orbitrap benchtop mass spectrometer (Q Exactive) using a vented column configuration.9 The column and trap were packed in-house with Magic C18AQ stationary phase (5 µm particle, 200 Å pore, Auburn, CA). Each sample was reconstituted in 25 µL mobile phase A which was composed of water/acetonitrile/formic acid (98/2/0.2%). 5 µL was then loaded onto the 75 µm × 5 cm trap (IntegraFrit, New Objective, Woburn, MA) at a flow rate of 3.5 µL/min using 100% mobile phase A. Mobile phase B comprised of water/acetonitrile/formic acid (2/98/0.2%). Flow was diverted onto the column the which began the start of the gradient: 2% B (0–5 min), 2%–5% B (5–7 min), 5%–40% B (7–208 min), 40%–95% (208–218 min), 95% (218–228 min), 95%–2% (228–230 min), 2% (230–240 min).

Global proteomics parameters were utilized on a Q Exactive platform.10 Full scan MS transients were acquired in the orbitrap with a 70 kFWHM resolving power at m/z = 200. The automatic gain control (AGC) target for MS acquisition was set to 1E6 with a maximum ion injection of 30 ms. All full scan spectra were acquired with an m/z range of 400 to 1,600. MS/MS acquisition was acquired in data dependent acquisition mode where the maximum MS/MS events were set to 12 and the dynamic exclusion was set to 30 sec. The resolving power for all MS/MS spectra was set to 17.5 kfwhm at m/z = 200 with a maximum ion injection time of 250 ms for an AGC target of 2E5.

Data Analysis

Proteome Discoverer was utilized for converting all RAW LC-MS/MS chromatogram files into an MGF format. The resulting MGF format was then searched using MASCOT (Matrix Science, Boston, MA)11 against a concatenated target-reverse Gallus gallus reference database (NCBI, Nov 2013). The data was also searched with a fixed carbamidomethyl (C) modification, while oxidation (M) and deamidation (NQ) were set to variable modifications and a maximum of 2 missed cleavages. The precursor ion search tolerance was set to 5 ppm and the fragment ion tolerance was set to ± 0.02 Da. Statistical filtering using a 1% false discovery rate for identifying protein was performed using ProteoIQ.12–14

Quantification of proteins was accomplished by calculating (Spectral Counts) SpCs and (Normalized Spectral Abundance Factor) NSAF values. A SpCs is calculated for each protein and that number coincides with the number of MS/MS spectra that result in the identification of a tryptic fragment belonging to that protein. SpCs is representative of the concentration of the protein identified in the within the sample. The higher number of MS/MS spectra identified results in a higher concentration for that specific protein. In order to compare relative concentrations of a protein between samples, NSAF values for each protein were calculated. NSAF values are calculated by taking the SpC for a given protein and dividing it by its length (L) to produce a spectral abundance factor (SAF) for each protein. SAF values normalize the concentration of each protein with respect to their lengths. Each individual protein’s NSAF value was calculated by dividing the SAF value by the total SAF values of all the proteins identified per sample.

Results

Protein Identification

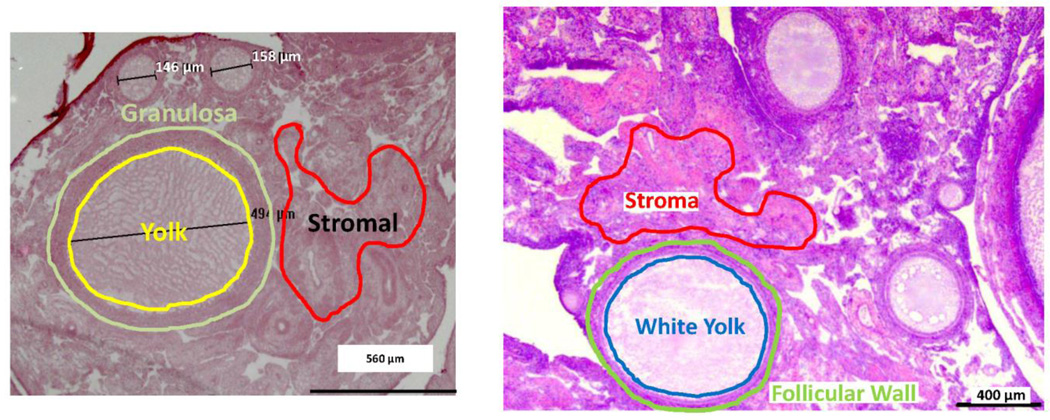

Figure 1 illustrates H&E stained avian ovary section outlining the three types of tissue compartments collected separately. First, white yolk components from follicles less than 1.6 mm with no presence of nuclei were pooled followed by excision of their complementing follicular walls. Next the adjacent stromal tissues from each of the follicles were collected and processed. In standard proteomic procedures, it is typical to consume a portion of the entire tissue when conducting a global proteomic profile. To represent an entire tissue sample, a “pooled” sample was collected from random regions. This included portions of the white yolk, follicular wall, and stromal tissue.

Figure 1.

H&E stained paraffin sections of ovarian tissue from an actively reproductive hen. Outlined are representative areas of white yolk, follicular wall and stromal cells excised by LMD for protein extraction.

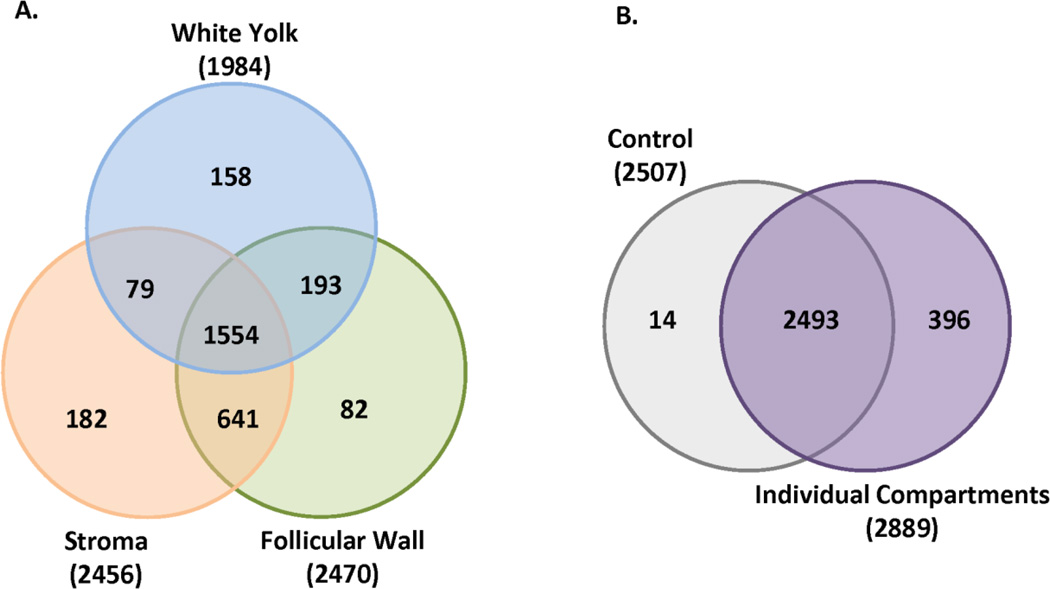

Figure 2a is a venn diagram which displays the distribution of identified proteins from each tissue compartment. A total of 2,889 proteins were identified from the three individual sample compartments. Most of proteins identified resulted from the ovarian stroma and the follicular wall cells, each with 2,456 and 2,470 proteins identified, respectively. Analysis of the white yolk resulted in the identification of 1,984 proteins. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive reported identification of proteins from the yolk of SWF and ovarian stroma in the laying hen. All proteins identified in the samples were annotated presented in Table S1 (supplementary material) with the following information; protein group, sequence ID, sequence name, protein length, protein weight, total peptides identified, total % sequence coverage, as well as spectral counts (SpC) and average normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF). A total of 2,507 proteins were identified in the “pooled” samples and represents 86.4% of all proteins identified, while 99.5% of all proteins were identified using the three compartments (Figure 2B). Therefore, an increase in proteome coverage was gained through the particular sub-sampling of tissue compartments with the use of LMD.

Figure 2.

(A) The number of proteins that were identified in white yolk, stromal cells and follicular wall of small white follicles of the avian ovary. A total of 1,984, 2,456 and 2,470 were identified in each compartment, respectively. (B) Random areas of the ovary were excised and analyzed. The “pooled” sampled resulted in a total of 2,507 proteins. 2,493 proteins overlapped with the 2,889 proteins that were identified in the individual compartments.

An added advantage of discovery-based proteomics methods is the ability to search data for post-translational modifications. All Proteins were searched with phosphorylation as a variable post-translation modification. A total of 91 proteins contained phosphorylated peptides (highlighted in purple in Table S1). A total of 4 peptides were identified as singly or doubly phosphorylated in both Vitellogenin I and II. Interestingly, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) protein had one peptide [SLFATQSQKTKIIQNR] identified with multiple phosphorylation sites. A total of four phosphorylation sites on EFGR were recognized in both the stromal tissue and follicular cells. For the stromal tissue, the Serine 1 and 7 positions on the EGFR peptide were phosphorylated as well as the Threonine 10. However phosphorylation sites in the follicular wall samples differed with phosphorylation of Threonine 5 but not the Serine 1 site.

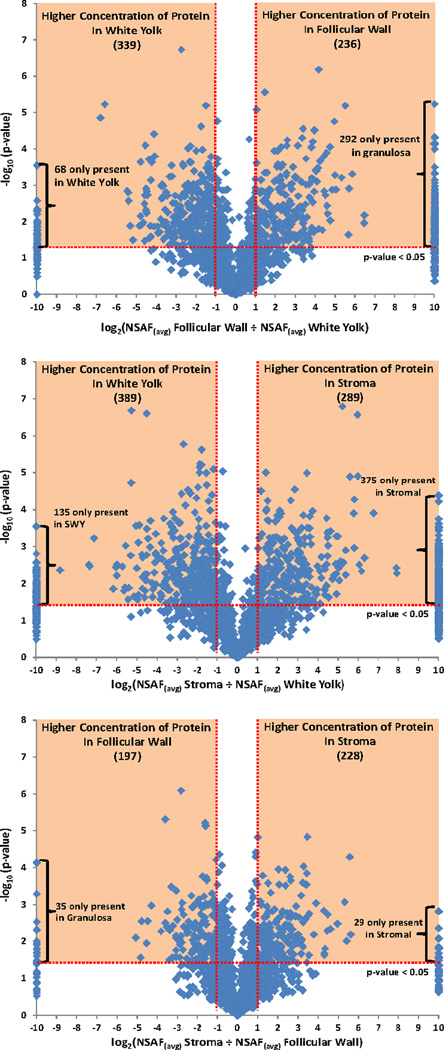

Global proteomic data can be daunting to analyze due to the large number of proteins identified. Proteins with greater than a two-fold difference in relative abundance that were statistically significant using a p-value cut-off of 0.05 were chosen for further analysis. Relative protein abundances between each compartment are displayed in Figure 3. Proteins observed in the orange shaded regions of the volcano plots were calculated with a greater than 2-fold change and statistically significant and were chosen for further analysis. From this subset, the DAVID algorithm program was used to obtain KEGG pathway analysis, cellular component and biological processes algorithms of the selected proteins.15 Table 1 lists the KEGG pathways identified from the proteins observed from the individual compartments. Characterization of white yolk proteins was of great interest due to the large discrepancy of proteins identified between white yolk proteins and published yellow egg yolk proteins. The top two GO annotations for cellular component classification resulted in “Cytoplasm” and “Cytoplamic part” with p-value scores of 5.6E-28 and 4.0E-18 respectively. The top scoring Biological Processes for the white yolk proteins was “generation of precursor metabolites and energy” with a p-value of 5.8E-8.

Figure 3.

Volcano plots graphing –log10(p-value) versus log2 expressions. Highlighted in orange are proteins with a greater than 2-fold higher abundance and statistically significant using a p-value of 0.05.

Table 1.

Identified KEGG Pathways Among Ovarian Tissue Compartments

| Stroma | Follicular Wall | White Yolk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Adhesion | X | X | |

| Ribsome | X | X | |

| ECM-receptor Interaction | X | X | |

| Spliceosome | X | X | |

| Tight Junction | X | X | |

| Adherens Junction | X | X | |

| Proteasome | X | ||

| Cardiac mudscle contraction | X | ||

| Vascular Smooth Muscle Contraction | X | ||

| Drug Metabolism | X | ||

| Regulation of Actin cytoskeleton | X | ||

| Glutathione metabolism | X | ||

| Glycolysis / glueconeogenesis | X | X | |

| arginine and proline metabolism | X | X | |

| citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | X | X | |

| lysine degradation | X | ||

| limonene and pinene degradation | X | ||

| histidine metabolism | X | ||

| pyruvate metabolism | X | ||

| oxidative phosphorylation | X | ||

| lysosome | X | ||

| RNA degradation | X | ||

| Endocytosis | X | ||

| Pentose phophate pathway | X |

Proteins Associated with Follicular Development

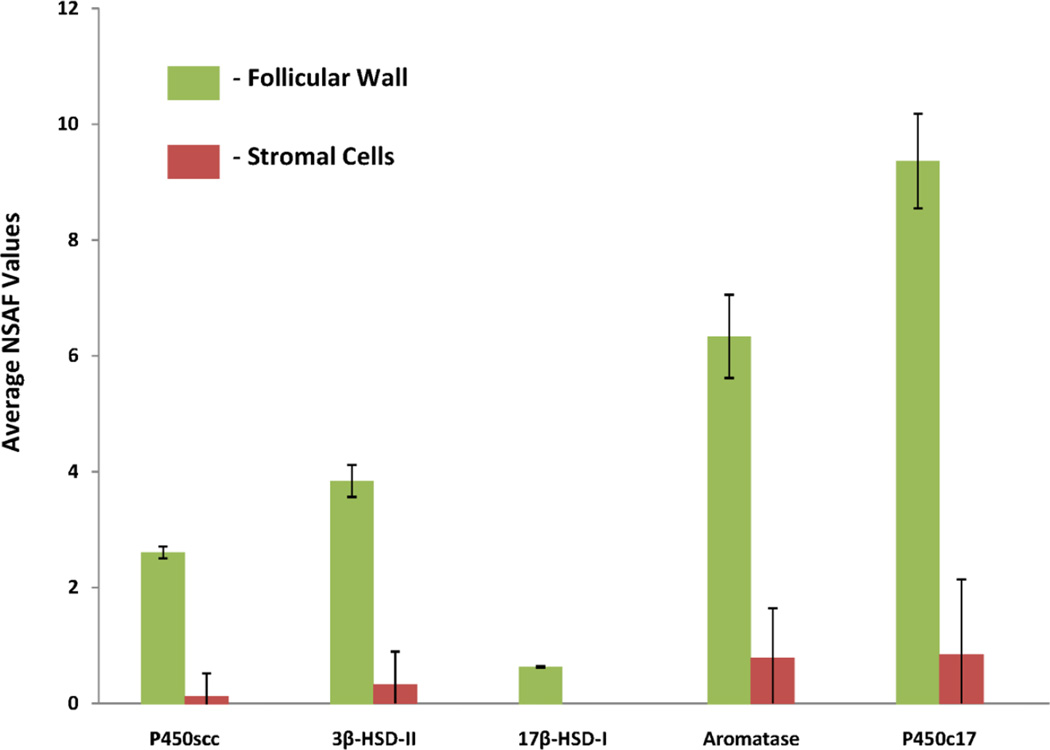

Many genes have been identified in follicles with respect to their association with follicular activation and development.5,16–18 Table 2 presents a list of gene names and their corresponding protein accession numbers of proteins known to the involved in the development of SWF.5,17,19,20 A few of the proteins were not detectable using LC-MS/MS techniques and can be attributed to low concentrations. Figure 4 shows all of the steroidogenic pathway proteins that were identified in their respective compartments. Relative quantification of each protein present is based on their spectral count (SpC) and normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF). The highest concentrations of steroidogeneic proteins were identified in the follicular wall cells with some trace proteins detected in the stromal tissue. However, StAR protein was not detected.

Table 2.

Known Genes Associated with Avian Follicular Development

| Gene Name | mRNA Present | Protein Accession Number - Protein Name | Protein Detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGA (FSH - Follicle Stimulating Hormone) | + | >gi|487441431|ref|NP_001264950.1| glycoprotein hormones alpha chain precursor | NA |

| FSHB (FSH - Follicle Stimulating Hormone) | + | >gi|259414634|gb|ACW82409.1| follicle stimulating hormone, beta polypeptide | NA |

| FSHR (Follicle Stimulating Hormone Receptor) | + | >gi|219663002|gb|ACL30987.1| follicle stimulating hormone receptor | NA |

| BMP6 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 6) | + | >gi|513170824|ref|XP_418956.4| PREDICTED: bone morphogenetic protein 6 | NA |

| SMAD 2 (Mothers Against Decapentaplegic Homolog 2) | + | >gi|17384013|emb|CAC85407.1| MADH2 protein | + |

| GATA4 | + | >gi|1169844|sp|P43691.1|Transcription factor GATA-4 | + |

| AMH (Anti-Mullerian Hormone) | + | >gi|1432158|gb|AAB04022.1| anti-Mullerian hormone | + |

| EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) | + | gi|119223|sp|P13387.1|EGFR_CHICK| Epidermal growth factor receptor | + |

| MAPK1 (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase, ERK2) | + | >gi|45383812|ref|NP_989481.1| mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | + |

| FOXL2 | + | gi|332646982|gb|AEE80502.1|Transcription Factor FOXL2 | + |

Figure 4.

The average normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF) values of the major steroidogenic enzymes detected in the follicular wall and adjacent ovarian stroma. No enzymes were detected in the white yolk of the follicles and StAR protein was absent in all compartments.

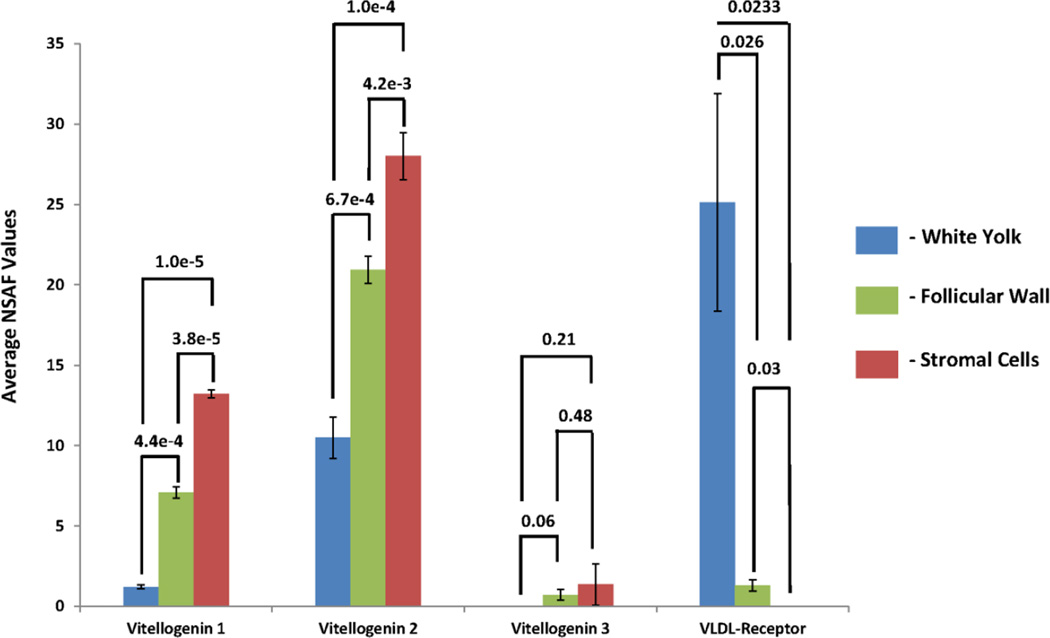

As follicles are recruited and enter the preovulatory hierarchy, they increase in size in large part through the accumulation vitellogenin. Since the SWF are in an undifferentiated state and are not actively sequestering yellow yolk, vitellogenins levels should be relatively low. Figure 5 shows the relative abundances of three types of vitellogenin and very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDL-receptor) found in each tissue compartment. Samples were taken from reproductively active hens with relatively high concentrations of vitellogenin in the circulation. As shown in Figure 5, vitellogenins are present at higher concentrations in the stroma, followed by the follicular wall cells. Follicles in an undifferentiated state are not actively growing and transporting nutrients into the yolk and a feature which is consonant with the small amounts of vitellogenin detected within the white yolk. On the other hand, VLDL-receptor was found to be primarily localized within the white yolk. Once the follicle enters follicular differentiation, the VLDL-receptors will migrate towards the follicular wall allowing for the endocytosis of vitellogenin into the yolk.

Figure 5.

The average normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF) values of vitellogenins 1–3 and VLDL-receptor with respect to their localization in the ovary. VLDL-receptor is located in the white yolk, while the vitellogenins remain mostly outside the yolk since the small yellow follicles have not undergone vitellogenenin accumulation.

Discussion

Global Protein Profile

Laser microdissection (LMD) was utilized for the separation of the yolk, follicular wall and stromal cells of small white follicles (SWF) obtained from reproductively active domestic fowl. To provide an in-situ proteomics-based approach to studying ovarian through the use of LMD and mass spectrometry, it was necessary to determine the amount of sample needed for efficient protein detection and to develop a means of estimating follicular diameter from sectioned tissue. Optimization of protein detection accomplished using liver sections, and about 2,480 proteins were identified in an area of 4.6-E7 µm2 and did not increase with increasing sample area. As a conservative sample from ovarian tissue, 8-E6 µm2 of material was chosen as the collection amount. In addition to sample area, the spherical nature of avian follicles presented another challenge. Typically, follicles are classified according to diameter. However, in histological section it is impossible to accurately classify follicles according to the apparent diameter found in the section since not all follicles are sectioned in the same plane of the sphere. To estimate true follicular diameter, diameters were measured for each follicle in serial sections and the increase or decrease in size was used to estimate the true diameter of the follicle. From this information, samples were taken from follicles ranging 0.3 – 1.6 mm. Lastly, we were able to divide the follicle into two sub-compartments, i.e. the follicular wall and the white yolk. All samples of white yolk were limited to cytoplasmic yolk and did not include the oocyte nucleus. Finally, adjacent ovarian stroma was sampled (see Figure 1).

Global proteomic profiles were provided for each compartment analyzed using LC-MS/MS. The white yolk proteome resulted in 1,984 proteins, while the ovarian stroma and follicular wall resulted in 2,456 and 2,470, respectively. Prior to this study, only proteomes of egg yolk plasma, granule and whites were documented.21–24 Previous studies have identified up to 158 proteins in the egg white24 while only 119 proteins were identified in the chicken egg yolk.23 The current study is the first report of proteins identified in yolk limited to SWF. The large number of yolk proteins from white yolk vs. yellow yolk is not unexpected, and it is likely that the highly abundant proteins such as vitellogenins, albumins and alpha-2-macroglobulins that are deposited during the development of the follicle can mask the detection of low concentration proteins. Generally, the growth in diameter of the follicle is the result of alternating layers of white and yellow yolk that surround a central “white yolk”, the latebra.25 The majority of the latebra as well as Pander’s nucleus are made up mainly of white yolk spheres. Yellow spheres constitute a majority of the yolk in a mature ovum. It can be proposed that the proteome identified in SWF is identical to the white yolk which constitutes the latebra, and implies that many more low concentration proteins exit in the mature egg than previously known.

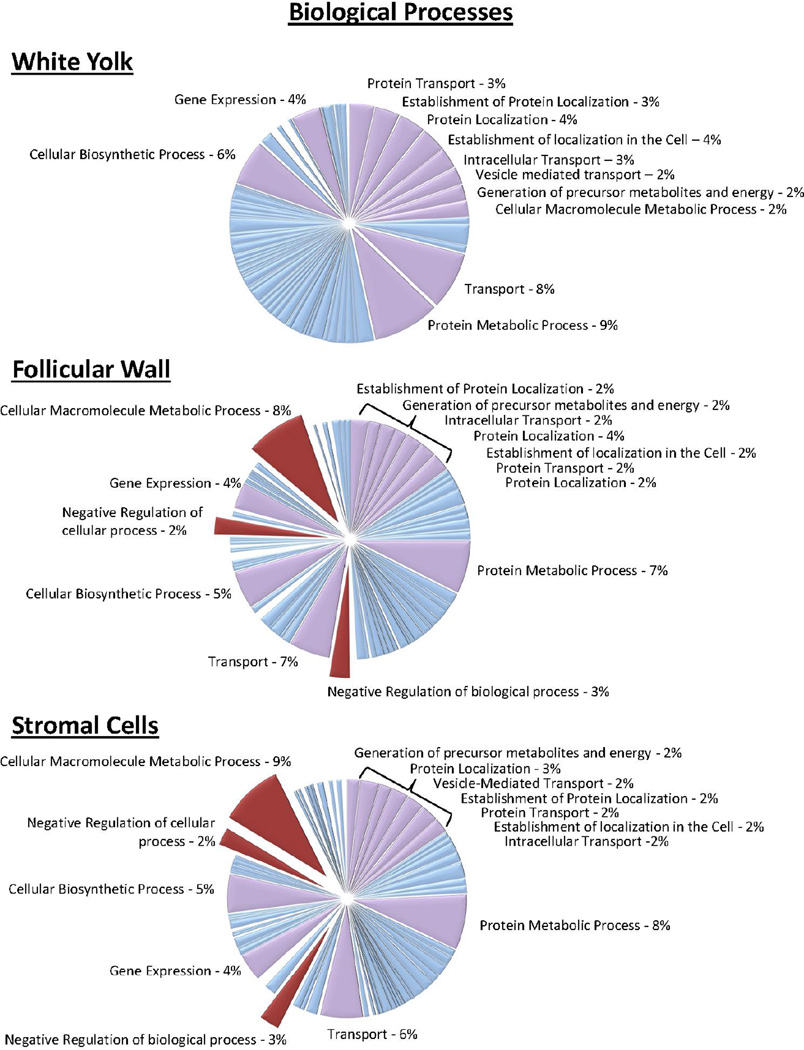

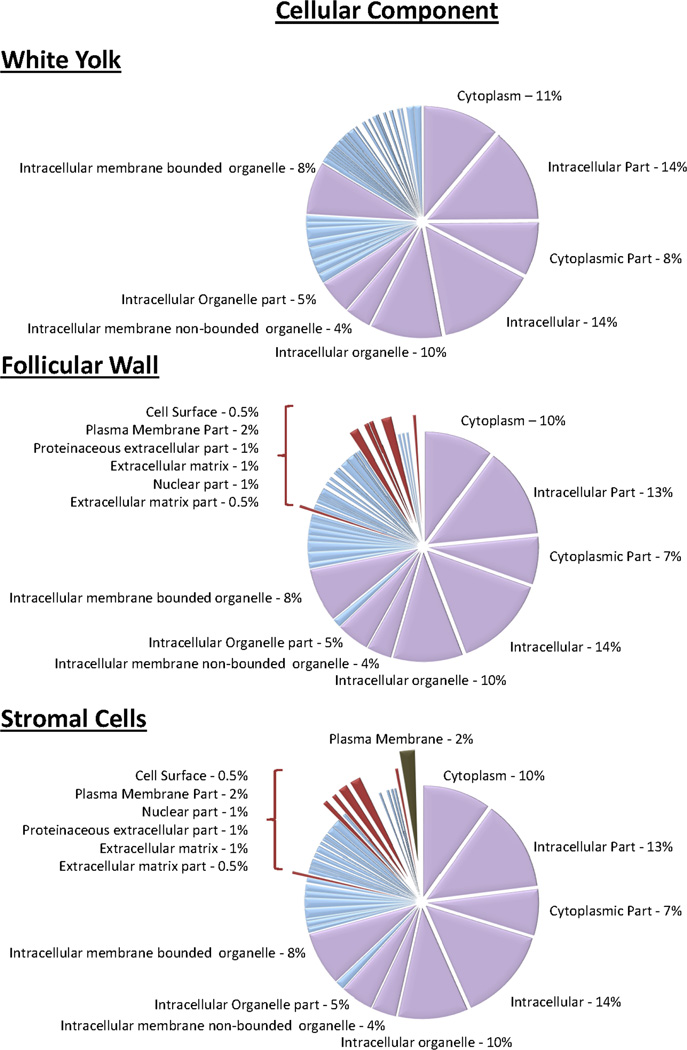

In the present study, 50, 53, and 53 mitochondrial proteins were identified in the white yolk, follicular wall and stroma compartments. The identification of mitochondrial proteins within the yolk samples agrees with Bellairs et. al. in which electron microscopy of small follicles in the chicken ovary revealed numerous mitochondrial structures lying at the periphery of the yolk adjacent to the granulosa cells of the follicular wall.26 The most statistically significant biological processes was “generation of precursor metabolites and energy”, this is likely due to the number of mitochondrial proteins identified. The DAVID Bioinformatics Database was used to categorize proteins found in their respective compartments based on biological processes and cellular component and Figure 6 illustrates the clustering of proteins based on biological processes. As shown in Figure 2, 1,554 proteins were proteins were identified in all three compartments. In Figure 6, the highlighted lavender pie pieces are some of the biological process shared throughout all three compartments. However, a few processes that were present in the follicular wall and stromal cell proteins but not yolk were cellular macromolecule metabolic process, negative regulation of biological process, and negative regulation of cellular process. These biological processes are important for regulation of cell death and atresia and are well documented in the regulation of avian follicular development. Figure 7 illustrates the classification of proteins based on their cellular component identified only in the follicular wall and stromal cells. The absence of proteins originating from cell surface, plasma membrane, extracellular matrix and the nucleus in the yolk sample supports that no nuclei or follicular wall cells were sampled from the white yolk of the follicles.

Figure 6.

Biological processes of the proteins identified from the individual compartments using DAVID algorithm. Major biological processes that differed from the follicular wall and stroma to that of the white yolk are highlighted in maroon.

Figure 7.

Cellular components of proteins identified from the individual compartments. Among the proteins in the follicular wall and stroma that were not identified in the yolk were associated with the extracellular matrix, cell surface, and nuclear proteins highlighted in maroon.

Protein Compartmentalization

Compartmentalization of proteins at the cellular and sub-cellular level are demonstrated in the detection of Vitellogenin 1, 2, 3. Figure 5 is a bar graph demonstrating average normalized spectral abundance factors (Avg-NSAF) of Vitellogenin 1, 2, 3 and VLDL receptor in the white yolk, follicular wall and stroma obtained from SWF. Concentrations of vitellogenin are greatest in the stromal tissue. Vitellogenins are yolk precursor proteins produced by the liver and circulate within the bloodstream till the follicle enters a stage of vitellogenesis in which endocytosis of vitellogenins transports them into the yolk. These proteins are essential for follicle development and final egg production and also provide nutrients to for the resulting embryo. SWF were obtained from healthy egg-producing hens, levels in which vitellogenins are expected to be high. While concentrations of vitellogenins were minimal within the white yolk of undifferentiated follicles, it is not uncommon for Vitellogenin 2 to be present in the yolk even at early stages. In striped bass, Vitellogenin 2 has been shown to enter the yolk preceding Vitellogenin 1 and 3.27 The proportional abundances of Vitellogenins 1, 2, 3 in the current study are similar to what was found in chicken egg yolk plasma and granule reported by Mann et. al..23 The opposite relationship was observed with very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) receptor protein. VLDL receptor mediates a key step in the reproductive effort of the hen, and, in the absence of VLDL receptor, oocytes are unable to enter the rapid growth phase of follicular development.28 These receptor proteins are maintained in the cytoplasm of the follicle until transport of lipoproteins are needed within the oocyte. They will then assemble towards the follicular wall allowing for endocytosis of essential lipoproteins. These results show that LCM allows for a discreet global proteomics analysis within different compartments of a tissue that could not be achieved otherwise.

Proteins Associated with Follicular Development

One of the hallmark events during follicular maturation and development of the avian egg is a shift in steroidogenesis from the Δ5-3β-hydroxysteroid pathway to the Δ4-3-ketosteroid pathway as the follicle matures.17 In the current study, allenzymes involved in the Δ5-3β-hydroxysteroid pathway were identified except for the StAR protein. Figure 4 shows the average normalized spectral counts (AvgNSpC) and the normalized spectral abundance factors (NSAFs) for the steroidogenic proteins. The steroidogenic enzymes were predominantly found in the follicular wall while minimal amounts were found in the stromal tissue. Steroidogenisis can occur in stromal tissue containing cortical follicles, producing significant amounts of estrogen.17 The absence of StAR protein corresponds with the transcript analysis of Johnson et. al. wherein undifferentiated cells from prehierarchal follicles fail to express StAR, while differentiated granulosa cells from the preovulatory follicles display an up-regulation of StAR leading to the production of progesterone.6 The small white undifferentiated follicles are known to be a major source of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), estradiol, and androsetendione17 and are produced through the Δ5-3β-hydroxysteroid pathway. When coupled with relatively high amounts of P450c17, pregnenolone is converted to DHEA. In turn, the DHEA is converted to androstenedione. With relatively lower amounts of the 17β-HSD-I protein, it can be suggested that not all the androstenedione is converted to testosterone. However, with higher amounts of aromatase present it is likely that all the testosterone is converted to estradiol. In the early stages of follicular development, studies have demonstrated estradiol as a key component in preventing follicular atresia.29, 30 The relative amounts of each steroid cannot be quantified based on solely the amounts of proteins present; however, the relative levels of the enzymes correlates well with the production of DHEA, androstenedione, and estradiol produced by gonadotropin-stimulated cultured small white follicles.17

Table 2 lists a collection of genes for which mRNA expression has been previously reported and involved in follicular development with their corresponding translated proteins, some of which were detected or not detected in our global proteome data. Among these, anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) is known to be involved in the regression of the Mullerian ducts in birds. In male birds the Mullerian ducts regress completely, while in females, only the right ducts regress allowing the left oviduct to develop. The left ovary is protected from the AMH due to the presence of estrogen.31, 32 Johnson and co-workers have used quantitative real time PCR to study Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) expression in the granulosa cells of various follicles sizes.33 Their study concluded that granulosa cells obtained from follicles of 1 mm in size had expressed the largest amounts of AMH over the larger follicles examined. Our global proteomics data indicated that AMH was present and only detected in the follicular wall cells. Other proteins identified that play a role in ovarian function were Retinoic Acid Receptor-alpha isoform 1, and retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (RALDH1, RALDH2, RALDH3). Retinoic acid (RA) is involved in numerous cell functions such as cell growth, differentiation and binds to nuclear receptors RAR and RXR to regulate gene expression.34, 35 However, RA is controlled by the expression of RA-synthesizing retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH1, RALDH2, RALDH3).36 Unlike AMH which is primarily found in the follicular wall cells, the RALDH family of enzymes was found mainly in the stromal and white yolk cells. Smith et. al. observed RALDH2 mRNA is expressed in the ovarian cortex.37 They concluded expression of RALDH2 and CYP26B1 potentially leads to the RA synthesis and degradation suggesting a conserved role for retinoic acid in vertebrate meiosis.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) are valuable biomarkers used to study the ovarian follicular maturation. Woods and co-workers have noted that follicles can express FSHR mRNA in 1–2 mm follicles.38 However, the highest levels occur in prehierarchal follicles (6–8 mm) and newly selected preovulatory follicles (9–12 mm). FSHR was not detected in the current study, possibly due to low concentrations in follicles between .3 – 1.6 mm. Woods et. al. studied three distinct stages of follicular maturation; undifferentiated granulosa cells obtained from preheirarchal follicles, granulosa cells in recently selected follicles (9–12 mm), and differentiated cells from the preovulatory follicles. Their study of undifferentiated granulosa cells demonstrated that the activation of either EGFR receptor mediated MAPK or PKC signaling suppresses FSH-induced StAR protein expression and progesterone production. In our study, the presence of EGFR, PKC, and MAPK proteins and the absence of StAR and FSHR protein agrees with mRNA data for undifferentiated granulosa cells presented by Woods and co-workers.

Typically in a global proteome study a large number of proteins are identified. Sorting through the data is a daunting task. A comprehensive analysis of all proteins identified is beyond the scope of the current study. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to note that several important transcription factors and signaling pathway proteins were also identified including GATA-4, SMAD2, and FOXL2. The GATA4 and FOXL2 were only detected in the follicular wall cells while SMAD2 was found at slightly higher concentration in the stroma than in the follicular wall. At the same time, not every protein thought to be active on the avian ovary was detected. BMP6 appears to have a role in follicular development. Ocόn-Grove and co-workers demonstrate that the concentration of BMP6 mRNA is greatest in small follicle (1 – 2 mm) and that levels decrease with the maturation of the follicle.20 Unfortunately, BMP6 was not detected in the proteomics data. Possibly, BMP6 was undetectable due to its low level in the system. This appears to be typical for low concentration cytokines and requires several enrichment steps to detect BMP proteins using mass spectrometry.39

Taken together, the results from this study demonstrate that LMD can be successfully employed for efficient global proteomics on avian ovarian follicles that are less than 2 mm in size. Furthermore, LMD allowed the fine-detail analysis of protein expression in small sub-compartments of the avian ovary. In addition, significant differences in protein abundances were identified between the compartments and reflected the known physiological functions within the ovary. An added feature of proteomic analysis is that it allows for the study of post-translational modifications. Though this study examined only follicles < 2 mm, the approach can be adapted to other stages of development to provide insight into the function of the avian ovary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Rebecca Barnes Wysocky for her technical assistance. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM087964), the W.M. Keck Foundation, and North Carolina State University.

References

- 1.Huang ES, Kao KJ, Nalbandov AV. Synthesis of sex steroids by cellular components of chicken follicles. Biology of reproduction. 1979;20(3):454–461. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod20.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onagbesan OM, Peddie MJ. Steroid secretion by ovarian cells of the Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) General and comparative endocrinology. 1988;72(2):272–281. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(88)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang SC, Bahr JM. Estradiol secretion by theca cells of the domestic hen during the ovulatory cycle. Biology of reproduction. 1983;28(3):618–624. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod28.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nitta H, Osawa Y, Bahr JM. Multiple Steroidogenic Cell Populations in the Thecal Layer of Preovulatory Follicles of the Chicken Ovary. Endocrinology. 1991;129(4):2033–2040. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-4-2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz FJ, Anthony K, Halfhill AN. Early avian follicular development is characterized by changes in transcripts involved in steroidogenesis, paracrine signaling and transcription. Molecular reproduction and development. 2011;78(3):212–223. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson AL, Solovieva EV, Bridgham JT. Relationship between steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression and progesterone production in hen granulosa cells during follicle development. Biology of reproduction. 2002;67(4):1313–1320. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.4.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gokce E, Franck WL, Oh Y, Dean RA, Muddiman DC. In-Depth Analysis of the Magnaporthe oryzae Conidial Proteome. Journal of Proteome Research. 2012;11(12):5827–5835. doi: 10.1021/pr300604s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nature Methods. 2009;6(5):359-U60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews GL, Shuford CM, Burnett JC, Jr, Hawkridge AM, Muddiman DC. Coupling of a vented column with splitless nanoRPLC-ESI-MS for the improved separation and detection of brain natriuretic peptide-32 and its proteolytic peptides. Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2009;877(10):948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randall S, Cardasis H, Muddiman D. Factorial Experimental Designs Elucidate Significant Variables Affecting Data Acquisition on a Quadrupole Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0693-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins DN, Pappin DJC, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(18):3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Analytical chemistry. 2002;74(20):5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical chemistry. 2003;75(17):4646–4658. doi: 10.1021/ac0341261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weatherly DB, Atwood JA, Minning TA, Cavola C, Tarleton RL, Orlando R. A heuristic method for assigning a false-discovery rate for protein identifications from mascot database search results. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2005;4(6):762–772. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400215-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome biology. 2003;4(5):P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson PA, Kent TR, Urick ME, Trevino LS, Giles JR. Expression of anti-Mullerian hormone in hens selected for different ovulation rates. Reproduction. 2009;137(5):857–863. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson FE, Etches RJ. Ovarian steroidogenesis during follicular maturation in the domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus) Biology of reproduction. 1986;35(5):1096–1105. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod35.5.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods DC, Haugen MJ, Johnson AL. Actions of epidermal growth factor receptor/mitogen-activated protein kinase and protein kinase C signaling in granulosa cells from Gallus gallus are dependent upon stage of differentiation. Biology of reproduction. 2007;77(1):61–70. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson AL, Woods DC. Dynamics of avian ovarian follicle development: Cellular mechanisms of granulosa cell differentiation. General and comparative endocrinology. 2009;163(1–2):12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ocon-Grove OM, Poole DH, Johnson AL. Bone morphogenetic protein 6 promotes FSH receptor and anti-Mullerian hormone mRNA expression in granulosa cells from hen prehierarchal follicles. Reproduction. 2012;143(6):825–833. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Ambrosio C, Arena S, Scaloni A, Guerrier L, Boschetti E, Mendieta ME, Citterio A, Righetti PG. Exploring the chicken egg white proteome with combinatorial peptide ligand libraries. Journal of Proteome Research. 2008;7(8):3461–3474. doi: 10.1021/pr800193y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann K. The chicken egg white proteome. Proteomics. 2007;7(19):3558–3568. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann K, Mann M. The chicken egg yolk plasma and granule proteomes. Proteomics. 2008;8(1):178–191. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann K, Mann M. In-depth analysis of the chicken egg white proteome using an LTQ Orbitrap Velos. Proteome science. 2011;9(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romanoff ALR, A J. The Avian Egg. J. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellairs R. The relationship between oocyte and follicle in the hen's ovary shown by electron microscopy. J. Embryol. Exp. Morph. 1965;13(2):215–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams VN, Reading BJ, Amano H, Hiramatsu N, Schilling J, Salger SA, Islam Williams T, Gross K, Sullivan CV. Proportional accumulation of yolk proteins derived from multiple vitellogenins is precisely regulated during vitellogenesis in striped bass (Morone saxatilis) Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological Genetics and Physiology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jez.1859. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nimpf J, Radosavljevic MJ, Schneider WJ. Oocytes from the Mutant Restricted Ovulator Hen Lack Receptor for Very Low-Density Lipoprotein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264(3):1393–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murata H, Ihara Y, Nakamura H, Yodoi J, Sumikawa K, Kondo T. Glutaredoxin exerts an antiapoptotic effect by regulating the redox state of Akt. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(50):50226–50233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urata Y, Ihara Y, Murata H, Goto S, Koji T, Yodoi J, Inoue S, Kondo T. 17Beta-estradiol protects against oxidative stress-induced cell death through the glutathione/glutaredoxin-dependent redox regulation of Akt in myocardiac H9c2 cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(19):13092–13102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng CS. Differential expression of c-Jun proteins during mullerian duct growth and apoptosis: caspase-related tissue death blocked by diethylstilbestrol. Cell and tissue research. 2000;302(3):377–385. doi: 10.1007/s004410000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng CS. Differential activation of MAPK during Mullerian duct growth and apoptosis: JNK and p38 stimulation by DES blocks tissue death. Cell and tissue research. 2001;306(1):27–34. doi: 10.1007/s004410100426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PA, Kent TR, Urick ME, Giles JR. Expression and regulation of anti-mullerian hormone in an oviparous species, the hen. Biology of reproduction. 2008;78(1):13–19. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.061879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niederreither K, Subbarayan V, Dolle P, Chambon P. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for early mouse post-implantation development. Nature Genetics. 1999;21(4):444–448. doi: 10.1038/7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakai Y, Meno C, Fujii H, Nishino J, Shiratori H, Saijoh Y, Rossant J, Hamada H. The retinoic acid-inactivating enzyme CYP26 is essential for establishing an uneven distribution of retinoic acid along the anterio-posterior axis within the mouse embryo. Genes & Development. 2001;15(2):213–225. doi: 10.1101/gad.851501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishimaru Y, Komatsu T, Kasahara M, Katoh-Fukui Y, Ogawa H, Toyama Y, Maekawa M, Toshimori K, Chandraratna RA, Morohashi K, Yoshioka H. Mechanism of asymmetric ovarian development in chick embryos. Development. 2008;135(4):677–685. doi: 10.1242/dev.012856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith CA, Roeszler KN, Bowles J, Koopman P, Sinclair AH. Onset of meiosis in the chicken embryo; evidence of a role for retinoic acid. BMC developmental biology. 2008;8:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woods DC, Johnson AL. Regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone-receptor messenger RNA in hen granulosa cells relative to follicle selection. Biology of reproduction. 2005;72(3):643–650. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.033902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razdorov GVS. The Use of Mass Spectrometry in Characterization of Bone Morphogenetic Proteins from Biological Samples. Tandem Mass Spectrometry - Applications and Principles. 2012 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.