Abstract

Background:

Although obesity is expected to be associated with intention to reduce weight, this effect may be through perceived overweight. This study tested if perceived overweight mediates the association between actual obesity and intention to control weight in groups based on the intersection of race and gender. For this purpose, we compared Non-Hispanic White men, Non-Hispanic White women, African American men, African American women, Caribbean Black men, and Caribbean Black women.

Methods:

National Survey of American Life, 2001–2003 included 5,810 American adults (3516 African Americans, 1415 Caribbean Blacks, and 879 Non-Hispanic Whites). Weight control intention was entered as the main outcome. In the first step, we fitted race/gender specific logistic regression models with the intention for weight control as outcome, body mass index as predictor and sociodemographics as covariates. In the next step, to test mediation, we added perceived weight to the model.

Results:

Obesity was positively associated with intention for weight control among all race × gender groups. Perceived overweight fully mediated the association between actual obesity and intention for weight control among Non-Hispanic White women, African American men, and Caribbean Black men. The mediation was only partial for Non-Hispanic White men, African American women, and Caribbean Black women.

Conclusions:

The complex relation between actual weight, perceived weight, and weight control intentions depends on the intersection of race and gender. Perceived overweight plays a more salient role for Non-Hispanic White women and Black men than White men and Black women. Weight loss programs may benefit from being tailored based on race and gender. This finding also sheds more light to the disproportionately high rate of obesity among Black women in US.

Keywords: Blacks, gender, obesity, perceived overweight, race, weight control

INTRODUCTION

All-cause mortality rate increases even with a moderate excess in weight and reaches about double for individuals with obesity (body mass index [BMI] >30) compared to those not obese.[1] This is mostly due to the effect of obesity on cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancers.[2] Over 60% of the US population is either overweight or obese.[2,3,4] In the US, with 300,000 attributable annual deaths, obesity is only second to cigarette smoking as the leading cause of death.[5] With the current trends,[4] a larger number of obesity associated mortality and morbidity is expected in the near future.[6] The existing trend in the epidemic of obesity has been attributed to the increase in unhealthy lifestyle rather than genetics.[2,3] These concerns have increased the attention of public health authorities to programs which promote intention for weight-loss.[7]

A considerable proportion of populations is contemplating with the weight loss and may have some weight loss intention.[8] Very few studies, however, have focused on factors associated with weight loss intention.[9] Information derived from research on correlates of weight loss may enhance the efficacy of weight control programs that target intention and behaviors related to weight change.[10] Such information may particularly enhance the impact of weight control programs among minority groups who suffer disproportionately high rates of obesity and its associated morbidity.[11,12] Although actual obesity[13] and perceived obesity[11] influence intention for weight loss,[11] very little is known about race-, ethnic-, and gender differences in the association between these factors.

The current study tested the mediation effect of perceived overweight on the association between actual obesity and intention for weight loss among sub-groups of populations based on the intersection of race, ethnicity, and gender. This study used data of the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) and provided nationally representative results for Blacks and Whites in the US.[14]

METHODS

National Survey of American Life was a survey completed between February 2, 2001, and June 30, 2003. The study has been approved by the Institute Review Board of the University of Michigan, MI. All participants provided written consent for participation.

Participants

The NSAL included 5,810 individuals including 3,516 African Americans, 1,415 Caribbean Blacks, and 879 Non-Hispanic Whites. We only included Non-Hispanic Whites, African Americans, and Caribbean Blacks if they were not under-weight (BMI <18.5).

National Survey of American Life has used a national household probability sampling. All participants were individuals 18 years and older.[14,15] Although African Americans were sampled from either large cities, other urban and rural area, Caribbean Blacks were exclusively sampled from large cities.

Interview

Data have been collected through face-to-face computer-assisted (86%) or telephone (14%) interview. Interviews have lasted an average of 140 min. All interviews were performed in English. The final response rate was 72.3% overall.

Measures

The study measured demographics factors such as age and gender. The study also collected self-reported data on socioeconomic factors such as employment status, education, household income (divided approximately into quartiles), marital status, and country region.

Obesity

Body mass index was calculated based on self-reported weight and height measures, which have shown to be highly correlated with BMI when is calculated using direct measures of height and weight.[16] This approach may result in underestimation of weight and overestimation of height,[17] leading to low estimates of overweight and obesity.[18] BMI was categorized to healthy weight (BMI between 18.5 and 24.9), overweight (BMI between 25.0 and 29.9), obesity class I (BMI between 30.0 and 34.9), obesity class II (BMI between 35.0 and 39.9), and obesity class III (BMI >40.0).

Perceived weight

Perceived overweight was measured using the following single item measure: Do you consider yourself very overweight, somewhat overweight, only a little overweight, just about right, or underweight? Responses included underweight, just about right, only a little overweight, somewhat overweight, and very overweight.

Intention for weight loss

The main outcome in this study was intention for weight loss, being asked with the following single item question: Are you currently trying to lose weight? Responses included yes, no, and don’t know.

Statistical analysis

We used Stata 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) for data analysis, using sub-population survey commands. Weight adjusted survey proportions were reported with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Survey logistic regressions were used for multivariable analysis, by considering BMI as the independent variable, perceived overweight as a mediator, and intention for weight loss as the dependent variable. Adjusted odds ratio and 95% CI were reported. P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

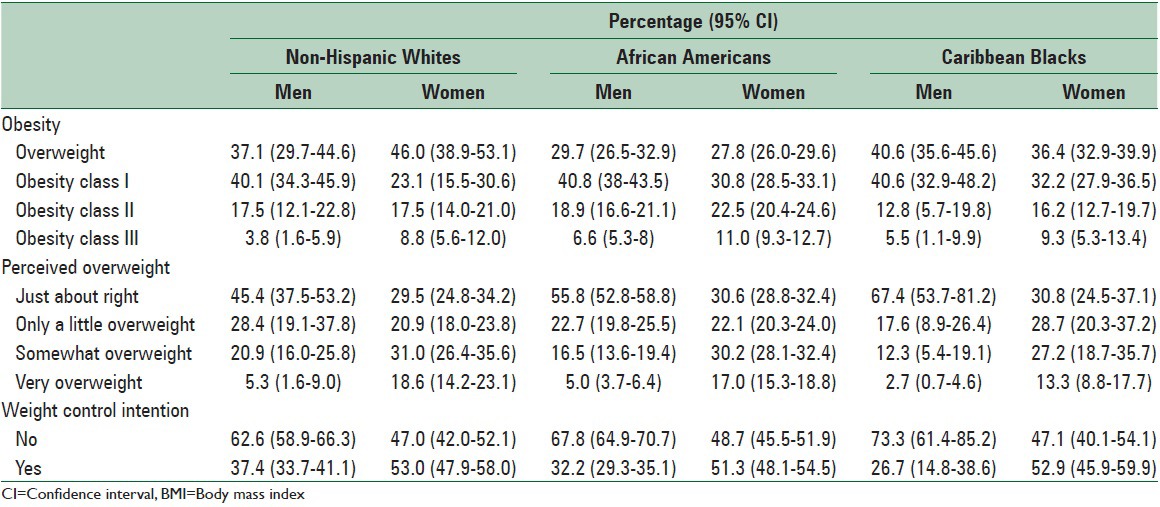

This study included a total sample of 5,810 adults that was composed of 3,516 African Americans, 1,415 Caribbean Blacks, and 879 Non-Hispanic Whites. Among all race and ethnic groups, compared with men, women reported higher overweight perception and intention to control weight [Table 1].

Table 1.

Descriptive of BMI, perceived weight, and intention to control weight among non-Hispanic White, African American and Caribbean Black men and women

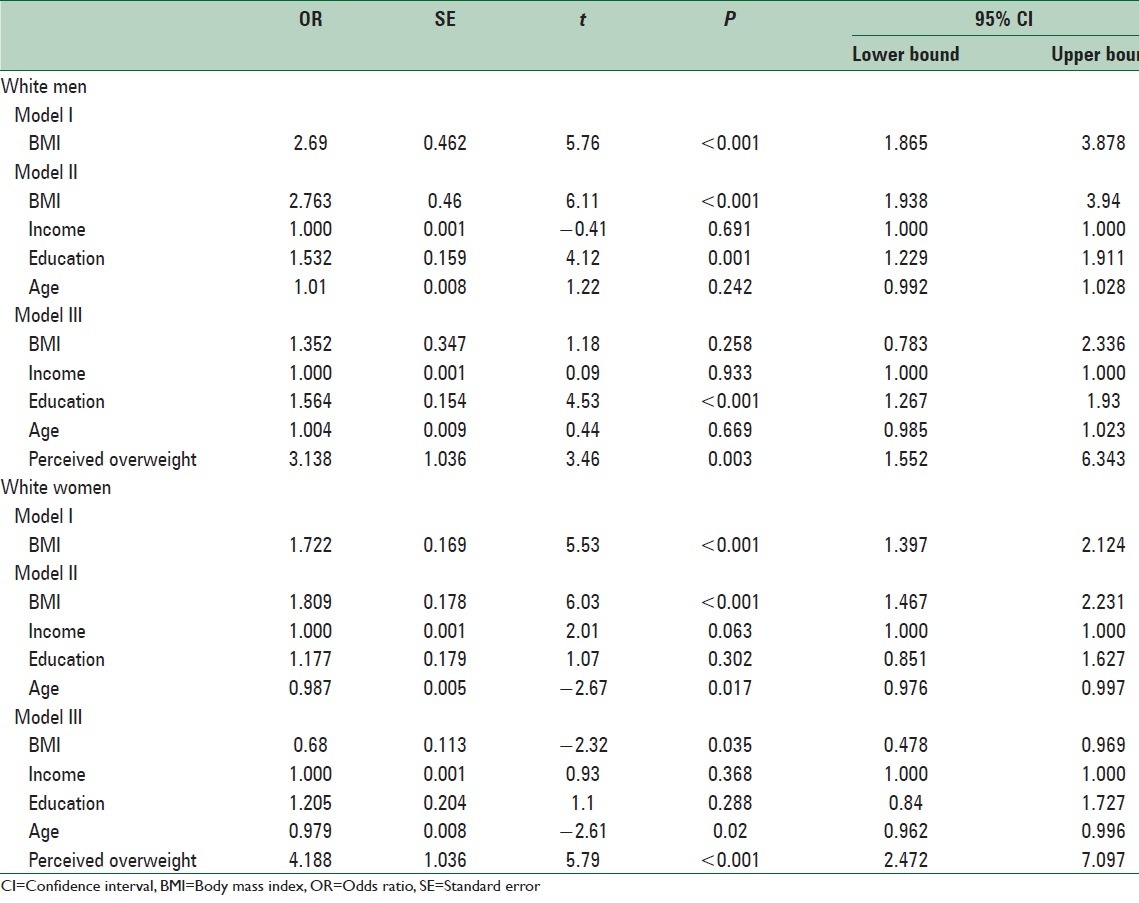

Non-Hispanic White men

Among Non-Hispanic White men, higher BMI was associated with higher odds of intention to control weight. This association remained significant after controlling the effect of income, education, and age. The BMI-intention to control weight association did not remain significant when we controlled for the effect of perceived overweight. In other words among Caribbean Black women, perceived overweight fully mediated the effect of actual BMI on intention to control weight [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association between BMI level and perceived overweight with intention to control weight among non-Hispanic white men and women

Non-Hispanic White women

Among Non-Hispanic White women, higher BMI was associated with higher odds of intention to control weight. This association remained significant after controlling the effect of income, education, and age. The BMI-intention to control weight association remained significant when we controlled for the effect of perceived overweight. This means that among Caribbean Black men, perceived overweight does not fully mediate the effect of actual BMI on intention to control weight [Table 2].

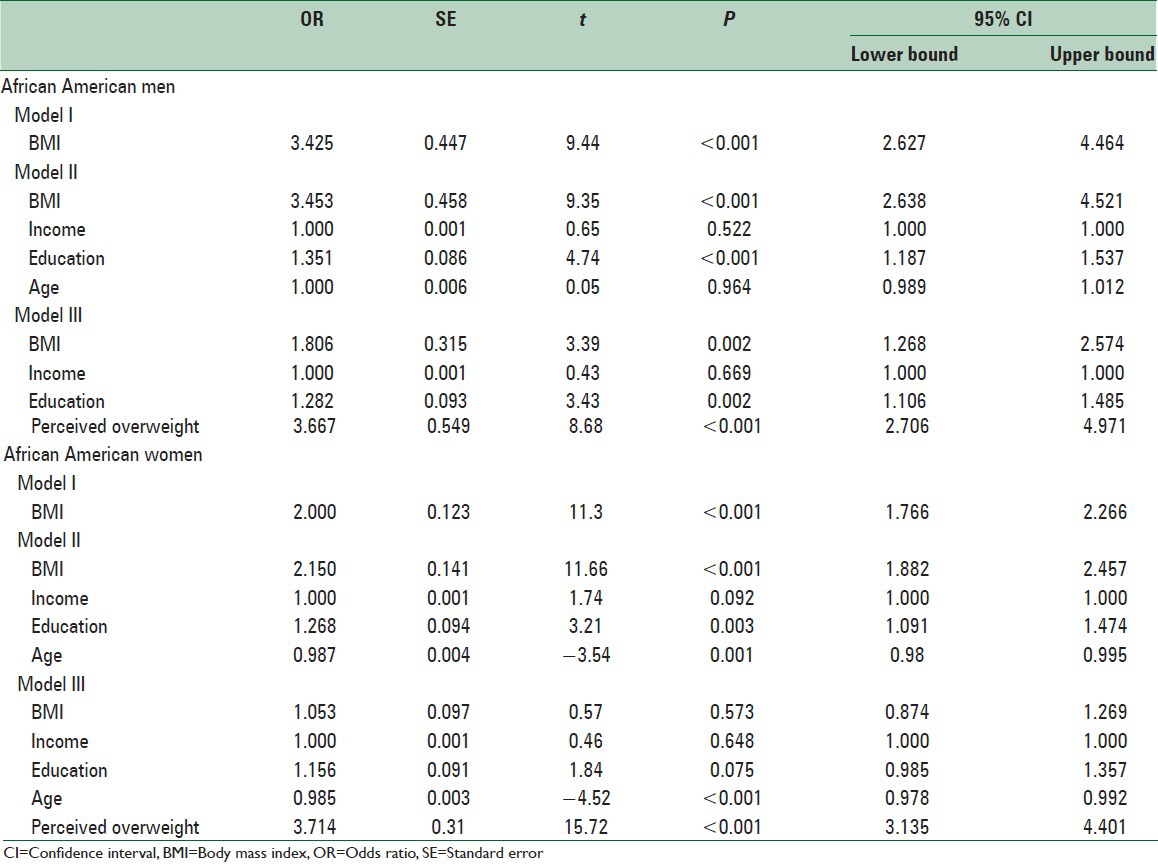

African American men

Among African American men, higher BMI was associated with higher odds of intention to control weight. This association remained significant after controlling the effect of income, education, and age. The BMI-intention to control weight association remained significant when we controlled for the effect of perceived overweight. This means that among African American men, perceived overweight does not fully mediate the effect of actual BMI on intention to control weight [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association between BMI level and perceived overweight with intention to control weight among African American men and women

African American women

Among African American women, higher BMI was associated with higher odds of intention to control weight. This association remained significant after controlling the effect of income, education, and age. The BMI-intention to control weight association did not remain significant when we controlled for the effect of perceived overweight. This means that among African American women, perceived overweight fully mediated the effect of actual BMI on intention to control weight [Table 3].

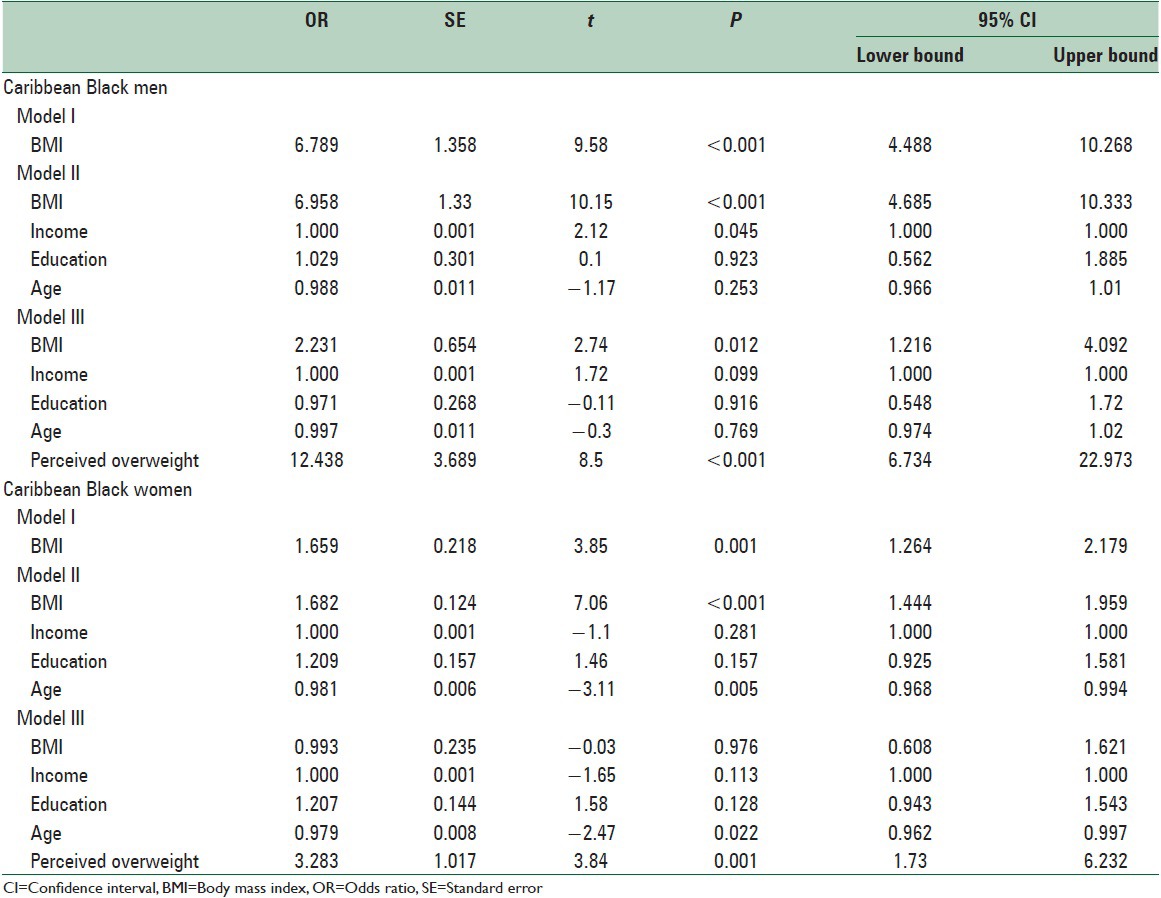

Caribbean Black men

Among Caribbean Black men, higher BMI was associated with higher odds of intention to control weight. This association remained significant after controlling the effect of income, education, and age. The BMI-intention to control weight association remained significant when we controlled for the effect of perceived overweight. This means that among Caribbean Black men, perceived overweight does not fully mediate the effect of actual BMI on intention to control weight [Table 4].

Table 4.

Association between BMI level and perceived overweight with intention to control weight among Caribbean Black men and women

Caribbean Black women

Among Caribbean Black women, BMI was positively associated with odds of intention to control weight. This association remained significant after controlling the effect of age, income, and education. The association between BMI and intention to control weight did not, however, remain significant when we controlled the effect of overweight perception. Thus, among Caribbean Black women, perceived overweight fully mediated the association between actual BMI and intention to control weight [Table 4].

CONCLUSIONS

The findings suggest that perceived overweight fully mediates the association between actual obesity and intention for weight control among White women and Black men but not White men and Black women.

Based on our study, half of overweight obese women and up to third of the overweight obese men have intention to control their weight. In one study, about 30% of Americans stated that at the time of study they were trying to reduce their calorie or fat intake in an effort to lose or maintain weight and 61% of them were doing more physical activity in order to lose or maintain weight.[8] In 2000, the American Dietetic Association reported that 28% of Americans reported an intention to change their eating behaviors to achieve a healthier diet at the time of the study.[19]

In line with the literature,[20] irrespective of race and ethnicity, women were more likely to identify themselves as overweight and take action to lose weight. Based on the literature, women, in general, are more motivated to lose weight, possibly due to perceived societal pressure to be thin and experiencing higher levels of concerns with their appearance. In addition, in general, women tend to be more health conscious.[21]

Our results in all race × gender groups and particularly among non-Hispanic White women and Black men are in support of the belief that cognition about obesity is a precursor of body dissatisfaction that leads to weight management behaviors among individuals with above-average weight. These behaviors may include an increased intake of fruits and vegetables, a lower intake of high-calorie foods and high physical activity.[22,23] Our study, however, shows that this effect may be less salient for Black women.

A number of studies have compared the body image perception between Whites and Blacks.[24,25,26,27] Among women, compared to Whites, Blacks may have fewer concerns about being overweight.[24] Black women may report lower body image dissatisfaction and may prefer larger body sizes than do other racial and ethnic groups.[28,29,30,31,32] Among women, compared to Whites, Blacks report fewer weight-related concerns, however, among men, race/ethnicity may not affect weight-related concerns.[28,33]

Although we already know that culture influences diet, physical activity, weight, intention to reduce weight, and weight-related behaviors such as exercise,[34] our information is limited on Black-White differences in the complex associations between the above factors that finally cause obesity. Very few studies have focused on race-, ethnic-, or gender-group differences in the way culture, attitudes, values, body image, norms, and perceived overweight affect weight-related behaviors and obesity.[35] Thomas posits that among ethnic minorities, historical, social, and cultural forces determine how attitudes and perceptions determine the lifestyle behaviors, which translate in obesity.[36]

Obesity is higher among Black Americans than other race and ethnic groups, with more than half being overweight or obese.[37,38,39,40] Approximately, 40% of Blacks report no leisure-time physical activity.[1,8] In fact, among women,[14,41] compared with Whites, Blacks are less likely to eat healthy foods, and may have higher social acceptance of heavier body weight and perceive less social pressure to lose weight,[9,42,43,44] which may result in lower weight management strategies.[45,46]

This study adds to our knowledge about racial and gender differences in the link between weight, perceived weight, and weight loss intention. Based on theories of reasoned action and planned behavior, intention the strongest predictors of behaviors.[47,48,49]

Our findings have important implications. As we know that culturally tailored interventions have higher efficacy among minority groups,[50,51] the result of this study may be used for tailoring healthy weight programs that are specifically designed for Blacks.[52,53] To reduce the obesity-attributable mortality,[54] effective weight loss programs that target minority populations[52,53] should be promoted in US. Even minimum weight loss may result in an evident reduction in mortality. Thus individuals with obesity should receive help to reduce their body weight.[55]

Weight control programs among minority populations – who are at an increased risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease[38,39,40] -may benefit by tailoring to race and gender of their target groups. Thus, the results of this study may increase the success of the program, which try to increase intention to weight loss in the US. This is especially important because weight loss is the key factor in the control and prevention of coronary heart disease, hypertension, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cardiorespiratory failure, and other chronic degenerative diseases,[56] and even a modest amount of weight control will reduce these risks.[57]

The study had a number of limitations. The first major limitation was with the measurement of study constructs. We used single items to measure overweight perception and intention for weight loss. Actual weight was also measured using self-reported weight and height. Our study did not measure other factors such as body image, perceived social pressure related to thinness, and other weight-related factors.[58,59] Behavioral presentation of intention to control weight (dieting/exercise) was not investigated as well. However, we already know that the intention is one of the strongest predictors of behaviors, and empirical data has shown that weight loss intention predicts weight loss.[60]

The associations between body weight, weight perception, body dissatisfaction, weight control intention, and weight control behaviors are not simple.[61,62,63,64,65] Our finding sheds more light on the role of race, ethnicity, and gender as possible moderators on the above links, and also provides an explanation for some of the inconsistencies in the literature on some of these associations.

We argue that universal models may fail to explain the links between weight, weight perception, and weight control behaviors among all populations. Studies which show racial and gender differences in the paths from obesity to readiness and intention for weight control may have important public health implications for health education initiatives and weight loss interventions.[66] Findings of the current study are in line with a well-developed literature that has shown race, ethnicity, gender, and their intersections modify correlates of obesity and cardiovascular risk.[67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]

To conclude, our study showed that the intersection of gender and race determines if perceived overweight fully mediates the association between perceived overweight and intention to control weight or not. The degree by which perceived overweight plays a role in the cognitive process by which one person with obesity makes a decision about weight loss may be under the influence of race and gender. Perceived overweight seems to be a more salient factor with stronger implications for weight control among White women and Black men than Black women and White men.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The NSAL is mostly supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, with grant U01-MH57716. Other support came from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health and the University of Michigan. For this analysis, public data set was downloaded from Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), Institute for Social Research at University of Michigan. The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Institute for Mental Health. Shervin Assari is supported by the Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Research Fund and the Richard Tam Foundation at the University of Michigan Depression Center.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Surgeon General. Overweight and Obesity: Health Consequences the Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. 2001. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44206/

- 2.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Troiano RP. Changes in the distribution of body mass index of adults and children in the US population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:807–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991-1998. JAMA. 1999;282:1519–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:2207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of overweight among adolescents – United States, 1988-91. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43:818–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JW, Luan J, Høie LH. Structured weight-loss programs: Meta-analysis of weight loss at 24 weeks and assessment of effects of intervention intensity. Adv Ther. 2004;21:61–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02850334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Division of Adult and Community Health, NCfCDPaHP, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveilance System Online Prevalence Data. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov .

- 9.Striegel-Moore RH, Wilfley DE, Caldwell MB, Needham ML, Brownell KD. Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of women who diet to lose weight: A comparison of black dieters and white dieters. Obes Res. 1996;4:109–16. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1996.tb00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll SL, Lee RE, Kaur H, Harris KJ, Strother ML, Huang TT. Smoking, weight loss intention and obesity-promoting behaviors in college students. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:348–53. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee RE, Harris KJ, Catley D, Shostrom V, Choi S, Mayo MS, et al. Factors associated with BMI, weight perceptions and trying to lose weight in African-American smokers. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:53–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JL, Eaton DK, Pederson LL, Lowry R. Associations of trying to lose weight, weight control behaviors, and current cigarette use among US high school students. J Sch Health. 2009;79:355–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNutt SW, Hu Y, Schreiber GB, Crawford PB, Obarzanek E, Mellin L. A longitudinal study of the dietary practices of black and white girls 9 and 10 years old at enrollment: The NHLBI Growth and Health Study. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:27–37. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Trierweiler SJ, Torres M. Methodological innovations in the National Survey of American Life. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:289–98. doi: 10.1002/mpr.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:221–40. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gavin AR, Rue T, Takeuchi D. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between actual obesity and major depressive disorder: Findings from the comprehensive psychiatric epidemiology surveys. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:698–708. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor AW, Dal Grande E, Gill TK, Chittleborough CR, Wilson DH, Adams RJ, et al. How valid are self-reported height and weight?. A comparison between CATI self-report and clinic measurements using a large cohort study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30:238–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Miglioretti DL, Crane PK, van Belle G, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:824–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Dietetic Association: American's Food and Nutrition Attitudes and Behaviors – American Dietetic Association's Nutrition and You: Trends. 2000. [Last accessed on 2005 May 25]. Available from: http://www.eatright.org/Public/Media/PublicMedia_10333.cfm .

- 20.Rand CS, Resnick JL. The “good enough” body size as judged by people of varying age and weight. Obes Res. 2000;8:309–16. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parmenter K, Waller J, Wardle J. Demographic variation in nutrition knowledge in England. Health Educ Res. 2000;15:163–74. doi: 10.1093/her/15.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinberg L. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. Body image dissatisfaction as a motivator for healthy lifestyle change: Is some distress beneficial? [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M. Does body satisfaction matter?. Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemper KA, Sargent RG, Drane JW, Valois RF, Hussey JR. Black and white females’ perceptions of ideal body size and social norms. Obes Res. 1994;2:117–26. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson DB, Sargent R, Dias J. Racial differences in selection of ideal body size by adolescent females. Obes Res. 1994;2:38–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Story M, Sherwood NE, Obarzanek E, Beech BM, Baranowski JC, Thompson NS, et al. Recruitment of African-American pre-adolescent girls into an obesity prevention trial: The GEMS pilot studies. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(1 Suppl 1):S78–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumark-Sztainer D, Croll J, Story M, Hannan PJ, French SA, Perry C. Ethnic/racial differences in weight-related concerns and behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: Findings from Project EAT. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:963–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel JM, Yancey AK, Aneshensel CS, Schuler R. Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:155–65. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altabe M. Ethnicity and body image: Quantitative and qualitative analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23:153–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199803)23:2<153::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gluck ME, Geliebter A. Racial/ethnic differences in body image and eating behaviors. Eat Behav. 2002;3:143–51. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parnell K, Sargent R, Thompson SH, Duhe SF, Valois RF, Kemper RC. Black and white adolescent females’ perceptions of ideal body size. J Sch Health. 1996;66:112–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson SH, Corwin SJ, Sargent RG. Ideal body size beliefs and weight concerns of fourth-grade children. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:279–84. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199704)21:3<279::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss RS. Self-reported weight status and dieting in a cross-sectional sample of young adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:741–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyington JE, Carter-Edwards L, Piehl M, Hutson J, Langdon D, McManus S. Cultural attitudes toward weight, diet, and physical activity among overweight African American girls. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blixen CE, Singh A, Thacker H. Values and beliefs about obesity and weight reduction among African American and Caucasian women. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17:290–7. doi: 10.1177/1043659606288375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas VG. Using feminist and social structural analysis to focus on the health of poor women. Women Health. 1994;22:1–15. doi: 10.1300/J013v22n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemic of obesity in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284:1650–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen SS, Signorello LB, Cope EL, McLaughlin JK, Hargreaves MK, Zheng W, et al. Obesity and all-cause mortality among black adults and white adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:431–42. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park Y, Hartge P, Moore SC, Kitahara CM, Hollenbeck AR, Berrington de Gonzalez A. Body mass index and mortality in non-Hispanic black adults in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cossrow N, Falkner B. Race/ethnic issues in obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2590–4. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simons-Morton BG, Baranowski T, Parcel GS, O’Hara NM, Matteson RC. Children's frequency of consumption of foods high in fat and sodium. Am J Prev Med. 1990;6:218–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenberg DR, LaPorte DJ. Racial differences in body type preferences of men for women. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:275–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199604)19:3<275::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell AD, Kahn AS. Racial differences in women's desires to be thin. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;17:191–5. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199503)17:2<191::aid-eat2260170213>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumanyika S, Wilson JF, Guilford-Davenport M. Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of black women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93:416–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)92287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parker S, Nichter M, Nichter M, Vuckovic N, Sims C, Ritenbaugh C. Body image and weight concerns among African-American and white adolescent females: Differences that make a difference. Hum Organ. 1995;54:103–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bronner Y, Boyington JE. Developing weight loss interventions for African-American women: Elements of successful models. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:224–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckman J, editors. Action-control: From Cognition to Behavior. Heidelberg: Springer; 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hale JL, Householder BJ, Greene KL. The theory of reasoned action. In: Dillard JP, Pfau M, editors. The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 259–86. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Sharp LK, Singh V, Dyer A. Obesity reduction black intervention trial (ORBIT): 18-month results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:2317–25. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, Davidson E, Bhopal R, White M, Johnson M, Netto G, et al. Adapting health promotion interventions to meet the needs of ethnic minority groups: Mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16:1–469. doi: 10.3310/hta16440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML, Schiffer L, Sharp LK, Singh V, Van Horn L, et al. Obesity reduction black intervention trial (ORBIT): Six-month results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:100–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nierkens V, Hartman MA, Nicolaou M, Vissenberg C, Beune EJ, Hosper K, et al. Effectiveness of cultural adaptations of interventions aimed at smoking cessation, diet, and/or physical activity in ethnic minorities. A systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poirier P, Després JP. Exercise in weight management of obesity. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19:459–70. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klein S. Outcome success in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(Suppl 4):354S–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pasanisi F, Contaldo F, de Simone G, Mancini M. Benefits of sustained moderate weight loss in obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2001;11:401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Thompson TJ, Williamson DF. Trying to lose weight, losing weight, and 9-year mortality in overweight U.S adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:657–62. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saarni S, Silventoinen K, Rissanen A, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Kaprio J. Intentional weight loss and smoking in young adults. Int J Obes. 2004;28:796–802. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leahey TM, Gokee LaRose J, Fava JL, Wing RR. Social influences are associated with BMI and weight loss intentions in young adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1157–62. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schifter DE, Ajzen I. Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;49:843–51. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.49.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brener ND, Eaton DK, Lowry R, McManus T. The association between weight perception and BMI among high school students. Obes Res. 2004;12:1866–74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Story M, Stevens J, Evans M, Cornell CE, Juhaeri, Gittelsohn J, et al. Weight loss attempts and attitudes toward body size, eating, and physical activity in American Indian children: Relationship to weight status and gender. Obes Res. 2001;9:356–63. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Viner RM, Haines MM, Taylor SJ, Head J, Booy R, Stansfeld S. Body mass, weight control behaviours, weight perception and emotional well being in a multiethnic sample of early adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1514–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forman-Hoffman V. High prevalence of abnormal eating and weight control practices among U.S. high-school students. Eat Behav. 2004;5:325–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bish CL, Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Marcus M, Kohl HW, 3rd, Khan LK. Diet and physical activity behaviors among Americans trying to lose weight: 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obes Res. 2005;13:596–607. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hawkins DS, Hornsby PP, Schorling JB. Stages of change and weight loss among rural African American women. Obes Res. 2001;9:59–67. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Assari S. Separate and Combined Effects of Anxiety, Depression and Problem Drinking on Subjective Health among Black, Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Men. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:269–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Assari S. The link between mental health and obesity: Role of individual and contextual factors. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:247–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Assari S. Cross-country variation in additive effects of socio-economics, health behaviors, and comorbidities on subjective health of patients with diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:36. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-13-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Assari S, Lankarani MM, Lankarani RM. Ethnicity Modifies the Additive Effects of Anxiety and Drug Use Disorders on Suicidal Ideation among Black Adults in the United States. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1251–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Assari S, Lankarani RM, Lankarani MM. Cross-country differences in the association between diabetes and disability. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:3. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Assari S. Race and Ethnicity, Religion Involvement, Church-based Social Support and Subjective Health in United States: A Case of Moderated Mediation. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:208–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bayat N, Alishiri GH, Salimzadeh A, Izadi M, Saleh DK, Lankarani MM, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression: A comparison among patients with different chronic conditions. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1441–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Assari S, Lankarani MM, Moazen B. Religious Beliefs May Reduce the Negative Effect of Psychiatric Disorders on Age of Onset of Suicidal Ideation among Blacks in the United States. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:358–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Assari S. Additive Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Body Mass Index among Blacks: Role of Ethnicity and Gender. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2014;8:44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Assari S. Chronic Medical Conditions and Major Depressive Disorder: Differential Role of Positive Religious Coping among African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:405–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Assari S. Association between obesity and depression among American blacks: Role of ethnicity and gender. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Assari S, Lankarani MM. The Association Between Obesity and Weight Loss Intention Weaker Among Blacks and Men than Whites and Women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2:414–20. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0115-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Assari S, Caldwell CH. Gender and ethnic differences in the association between obesity and depression among black adolescents. Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015:2. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0096-9. DOI 10.1007/s40615-015-0096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]