Abstract

The goal of this paper is to draw attention to the long lasting effect of education on economic outcomes. We use the relationship between education and two routes to early retirement – the receipt of Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) and the early claiming of Social Security retirement benefits – to illustrate the long-lasting influence of education. We find that for both men and women with less than a high school degree the median DI participation rate is 6.6 times the participation rate for those with a college degree or more. Similarly, men and women with less than a high school education are over 25 percentage points more likely to claim Social Security benefits early than those with a college degree or more. We focus on four critical “pathways” through which education may indirectly influence early retirement – health, employment, earnings, and the accumulation of assets. We find that for women health is the dominant pathway through which education influences DI participation. For men, the health, earnings, and wealth pathways are of roughly equal magnitude. For both men and women the principal channel through which education influences early Social Security claiming decisions is the earnings pathway. We also consider the direct effect of education that does not operate through these pathways. The direct effect of education is much greater for early claiming of Social Security benefits than for DI participation, accounting for 72 percent of the effect of education for men and 67 percent for women. For women the direct effect of education on DI participation is not statistically significant, suggesting that the total effect may be through the four pathways.

Keywords: Education, Retirement, Disability Insurance, Social Security

1. Introduction

The central goal of this paper is to draw attention to the long lasting influence of education. It is of course not news that education is an important determinant of a person’s life course. The focus in this paper is the relationship between the level of education and two routes to early retirement. One is through the Social Security Disability Insurance program (DI), with very few people leaving DI once accepted. The second is through the early claiming of Social Security retirement benefits by those who have not already retired through the DI program. These routes are used disproportionately by those who are ill-prepared to work longer because of health or other reasons. The analysis brings to the fore just how important and long-lasting the influence of education can be. The magnitude of the “education effect” on these retirement outcomes is likely to be surprising to many readers. The results illustrate not only the enormous influence of education but also that change in the breadth and depth of education may play an important role in improving preparation for retirement in the future. To confront a wide range of problems that we face it will likely be necessary to address the critical role played by education. Early retirement is simply an example to bring attention to the far-reaching influence of a key foundation for well-being throughout the life course.

Although the focus of this paper is on the far reaching effect of education, the outcome we consider – early retirement – is itself an important policy issue for at least two reasons. First, delaying retirement can have a positive effect on the financial sustainability of the Social Security system. In addition, the nearly 8 percent increase in benefits for each year that claiming is delayed provides a substantial benefit to those for whom delaying claiming is feasible.

We begin by considering the relationship between education and the receipt of DI benefits for persons between the ages of 50 and 62. Then we consider the early claiming of Social Security benefits by persons between the ages of 62 and 65 who are not receiving DI benefits at 62. Education may affect DI participation and early claiming of Social Security benefits in many ways. For both routes to retirement we emphasize four critical pathways – health, employment, earnings, and the accumulation of assets – through which education may indirectly influence early retirement decisions. Education may affect DI decisions or the early claiming of Social Security benefits indirectly through each of these pathways. But education may also have an additional direct effect on both routes to retirement that does not operate through the designated pathways. We estimate both the direct and indirect influence of education on these routes to retirement. In doing so we use two different estimation methods to provide estimates of the upper and lower bounds for the direct and indirect effects of education.

Several recent papers – Autor, Katz and Kearney (2008), Goldin and Katz (2008), and Agemoglu and Autor (2012) for example – emphasize the changing education composition of the workforce and its lasting effects in the labor market. They consider the relationship between educational trends and the restructuring of the U.S. labor market in recent decades. In particular, they highlight the concern that the growth in the education of the workforce has failed to keep pace with the growth of high-skill jobs. One widely studied consequence has been growing earnings inequality or “job polarization.” Here, we emphasize another critical aspect of the effect of education on labor market experience: the relationship between education and routes to retirement.

We recognize that the pathway approach that we present is only one possible way of exploring the relationship between education and DI participation and between education and the early claiming of Social Security benefits. There are at least two issues that arise in this regard. One is that we focus attention on four pathways, but there may be others. For example one of the pathway variables to DI participation (and perhaps more so to early claiming of Social Security benefits) might be life expectancy. That is, education affects life expectancy which in turn affects the decision to delay receipt of Social Security benefits. We do not include life expectancy but we do include health which is strongly related to life expectancy

A second, and related issue, is the extent to which the relationship between education and each of the pathways is causal. For example, education and earnings are strongly related, but the extent to which this relationship is causal has been a long-standing issue in economics. Card (1999), in his survey of the literature on the effect of education on earnings, puts in this way: “it is very difficult to know whether the higher earnings observed for better-educated workers are caused by their higher education, or whether individuals with greater earning capacity have chosen to acquire more schooling.” Another example is that childhood health may affect both educational attainment and late-life health. Thus part of what may appear to be an effect of education may actually be the effect of health. In the analysis that follows we measure the association between education and each pathway (and the association between each pathway and early retirement), but we make no attempt to determine the proportion of the association that might be considered causal. In this paper “education” is taken to be a marker for all that accompanies education without attempting to explore the mechanisms underlying the strong positive association between education and pathways to retirement. Rather, the goal is to highlight the magnitude of the relationship between education and an important life event – early retirement.

For ease of exposition, however, we often use the term “effect” to describe the relationship (either indirectly through the pathways or directly) between education and DI or early claiming of Social Security benefits.

The remainder of the paper is in four sections. Section 1 presents descriptive data that help to motivate and support the more formal analysis that follows. Section 2 presents the analysis of DI participation. Section 3 presents the analysis of the early claiming of Social Security benefits. Section 4 is a summary and discussion.

2. Descriptive data

The descriptive data emphasize the substantial relationship between education and the pathway variables – health, employment, earnings, and assets – through which education is assumed to influence DI participation and the early claiming of Social Security benefits. We begin by describing the striking relationship between education and DI participation and early claiming of SS benefits and then turn to the relationship between education and the pathway variables.

2.1 Disability Insurance and Early Claiming of SS Benefits

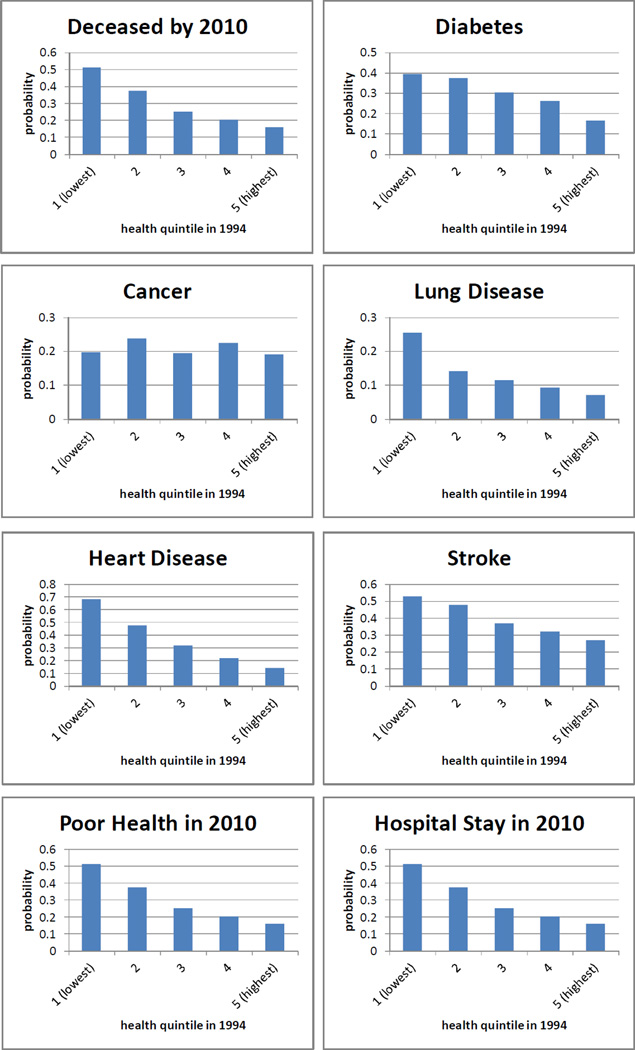

Table 1 shows the proportion of women and men who ever applied for and who ever received DI, by level of education and health status. The table is based on pooled data for the years 1994 to 2010 from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Health status is indicated by health quintile which is based on a health index that is explained below. The top panel shows the proportion of persons age 50 to 62 who ever applied for DI benefits. The middle panel shows the proportions that received DI. Both education and health are strongly related to DI receipt. The range of proportions across health quintiles exceeds the range of proportions across education groups. For example, among women 47 percent of those in the lowest health quintile receive DI, but only 3 percent of those in the top health quintile receive DI. For men the respective percentages are 56 percent and 4 percent. For women, 25 percent of those with less than a HS degree receive DI compared to 5 percent for women with a college education. Of men with less than a high school degree, 27 percent receive DI compared to 5 percent for those with a college degree or more. A key feature of the table is that within each health quintile, persons with low levels of education are much more likely to receive DI than those with more education. For example, for women in the poorest health, 51 percent with less than a high school degree receive DI compared to 35 percent for those with a college degree or more. In the top health quintile 11 percent of women with less than a high school degree receive DI, but only 1 percent of women with a college degree or more receive DI. The pattern for men is very similar.

Table 1.

The proportion of persons who ever applied for SSI or SSDI, the proportion between the ages 50 and 62 who were ever received SSI or SSDI, and the proportion between the ages 62 and 64 who claimed Social Security benefits early, by gender, by health quintile, and by education

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applied for DI | ||||||||||||

| Health quintile | Health quintile | |||||||||||

| Education | 1st (low) |

2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | All | 1st (low) |

2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | All |

| < HS | 0.76 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.36 |

| GED or HS grad | 0.61 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| Some college | 0.62 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| College or more | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| All | 0.64 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.72 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| Received DI | ||||||||||||

| 1st (low) |

2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | All | 1st (low) |

2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | All | |

| < HS | 0.51 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.27 |

| GED or HS grad | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.57 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Some college | 0.48 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| College or more | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| All | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.13 |

| Early Social Security claiming | ||||||||||||

| 1st (low) |

2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | All | 1st (low) |

2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | All | |

| < HS | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.66 |

| GED or HS grad | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| Some college | 0.75 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| College or more | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.4 |

| All | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.52 |

An interesting feature of Table 1 is that the percentage of applicants that are approved (the ratio of the middle panel to the top panel) is much higher for those with more education. This suggests that given application, more educated applicants are “more” disabled that less educated applicants. The types of functional limitations that prevent re-employment in white collar jobs may be quite different (and perhaps more severe) than those that prevent a return to work in blue collar jobs. We do not have detailed information on the type of disability to verify this explanation, but the issue deserves additional research.

The bottom panel of Table 1 shows the proportion of persons – not on DI at age 62 – claiming Social Security benefits before the normal retirement age. Overall 71 percent of women with less than a HS degree claim Social Security benefits early but only 44 percent of those with a college degree or more claim early. For men, 66 percent of those with less than a HS degree claim Social Security benefits early compared to only 40 percent of those with a college degree or more. Again, there is considerable variation in early claiming rates within each health quintile.

2.2 The Pathway Variables and Education

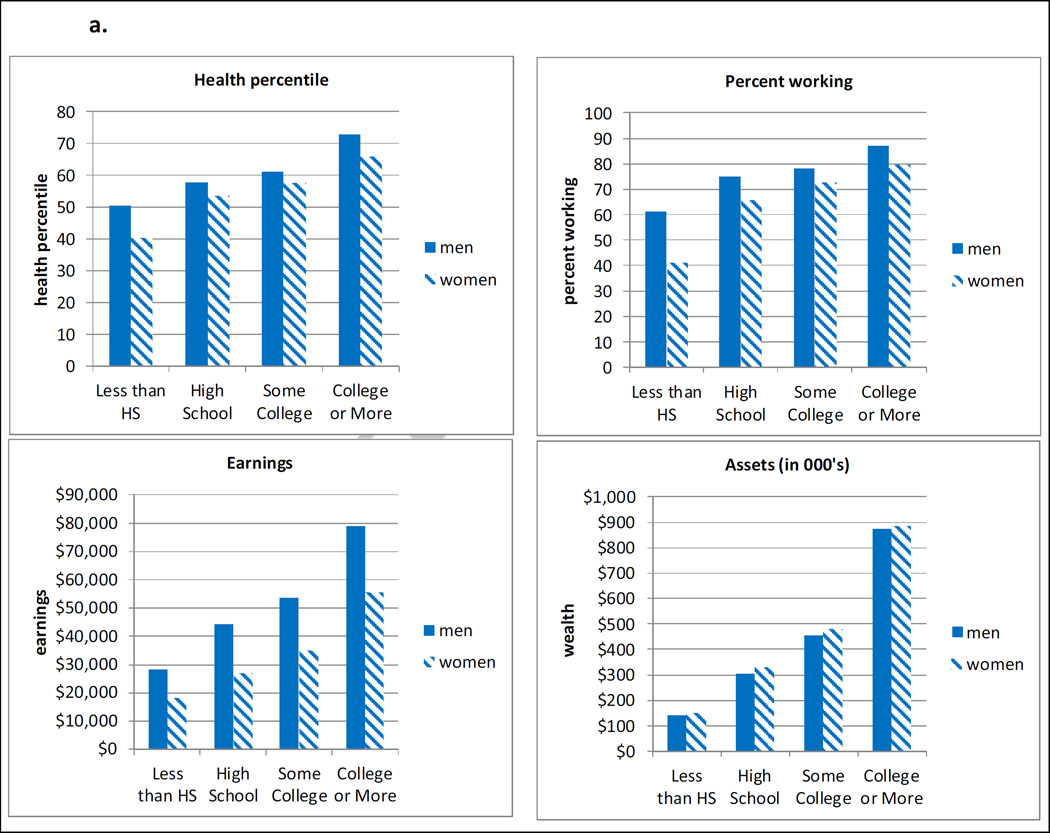

The empirical model we develop below considers how education may influence DI participation, and then the early claiming of Social Security benefits, through four pathways – health, employment, weekly earnings, and accumulated assets. Figure 1a shows four subpanels for persons 50 to 59 – health, employment, weekly earnings, and accumulated assets. The panels show that there are large differences by level of education for each of these pathways, highlighting the “education advantage.” We see that those with more education are in much better health, are more likely to be working between the ages of 50 and 59, earn much more, and have much greater assets.1

Figure 1.

a. Differences in pathway variables by level of education for persons age 50–59

b. Differences in pathway variables by level of education for persons age 60 to 61

Figure 1b shows four analogous panels but for persons 60 to 61 who are not on DI. This is to show the relationship between education and each pathway for persons eligible to claim early Social Security benefits. Health, earnings, and assets are strongly related to level of education. There is also a noticeable relationship between education and the proportion working at ages 60 and 61, especially for women.

2.3 The Health Index

The health index used to construct the quintiles in Table 1 and the health panels in Figures 1a and 1b, as well as the empirical analysis in sections 3 and 4, is the first principle component of 27 health indicators reported in the HRS. Construction of the index and its properties are described in some detail in Poterba, Venti, and Wise (2013a). For convenience, an updated version of that discussion is reproduced in the Appendix to this paper.

How long a person expects to live may be an important consideration in the timing of the receipt of Social Security benefits, with those expecting short lives more likely to claim benefits earlier. As noted above, we do not include subjective life expectancy as one of the pathways through which education influences DI, or in particular, the early claiming of Social Security benefits. We do, however, include health, and both subjective and actual mortality are likely to be strongly related to health. Table 2 below, calculated from the mortality model in Heiss, Venti, and Wise (2014), shows simulated actual life expectancy at age 66 for men and women, by level of education and selected health deciles.2 These simulations show that life expectancies for those in good health are more than double life expectancies for those in poor health. This suggests that our health index captures much of the variation in mortality. The variation across education levels is not quite as dramatic: on average, men with a college degree or more are expected to live about 3.8 years longer than men without a high school degree. For women the difference in life expectancies is 4.5 years. Simulated life expectancies by gender and age generated by this model closely match actual life tables. We use the simulated life expectancies because actual life expectancies are not available by level of education and health status.

Table 2.

Life expectancy at age 66, by level of education, gender and selected health deciles at age 66

| Level of Education | Health Decile a Age 66 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | All | |

| Men | |||||||

| Less than high school | 9.33 | 13.19 | 15.10 | 16.01 | 18.32 | 21.45 | 15.58 |

| High school degree | 10.31 | 14.28 | 16.35 | 17.22 | 19.55 | 22.63 | 16.77 |

| Some college | 10.71 | 14.73 | 16.88 | 17.67 | 20.03 | 23.10 | 17.24 |

| College or more | 12.79 | 17 03 | 19.15 | 19.91 | 22.27 | 25.03 | 19.40 |

| All | 10.66 | 14.68 | 16.73 | 17.57 | 19.91 | 22.93 | 17.12 |

| Less than high school | 10.06 | 14.62 | 17.03 | 18.12 | 20.74 | 24.21 | 17.51 |

| Women | |||||||

| High school degree | 12.26 | 17.21 | 19.67 | 20.54 | 23.13 | 26.26 | 19.90 |

| Some college | 12.94 | 17.96 | 20.40 | 21.27 | 23.76 | 26.81 | 20.59 |

| College or more | 14.42 | 19.50 | 21.91 | 22.75 | 25.03 | 27.92 | 22.01 |

| All | 12.11 | 16.99 | 19.42 | 20.35 | 22.88 | 26.05 | 19.69 |

2.4 The Accumulation of Assets

One of the pathways we emphasize is accumulated assets at retirement. Mean asset balances by level of education are shown in Table 3 and the share of total assets held in each asset type is shown in Table 4. The total assets of those with a college degree or more are 4.5 times as large as the total assets of those with less than a high school degree. The share of assets held in different asset types also varies greatly. Social Security wealth accounts for almost 50 percent of the total assets of those with less than a high school degree but only about 16 percent of the assets of those with a college degree or more.3 Almost 23 percent of the total assets of those with a college degree or more are in financial assets but only about 8 percent of the total assets of those less than high school degree is in financial assets. Almost 20 percent of the total assets of those with a college degree or more is in personal retirement accounts (401(k)s, IRAs, Keoghs and similar tax-advantaged retirement accounts) but only 4 percent of the total assets of those with less than a high school degree is in personal retirement accounts. Overall, non-annuity assets account for about 73 percent of the wealth of those with a college degree or more but only about 41 percent of the wealth of those with less than a high school degree.

Table 3.

Mean assets for households aged 65–69 in 2010 by level of education and marital status

| Asset Category | < High School |

High School |

Some College |

College or More |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Households | ||||

| Financial Assets | 28,335 | 70,401 | 103,331 | 354,487 |

| Non-Mortgage Debt | −2,975 | −6,961 | −7,860 | −3,781 |

| Home Equity (primary | 62,575 | 121,220 | 133,501 | 252,521 |

| Home Equity (second home) | 7,834 | 12,575 | 18,453 | 52,857 |

| Other Real Estate | 17,607 | 34,447 | 32,172 | 112,542 |

| Business Assets | 13,866 | 29,922 | 30,505 | 69,504 |

| Personal Retirement | 13,925 | 70,768 | 99,980 | 306,760 |

| - IRAs & Keoghs | 11,497 | 49,831 | 74,208 | 189,521 |

| − 401 (k)s and Similar Plans | 2,428 | 20,936 | 25,772 | 117,240 |

| Social Security | 172,992 | 228,127 | 238,789 | 242,646 |

| Defined Benefit Pension | 33,279 | 67,641 | 94,639 | 172,316 |

| Non-Annuity Net Worth | 141,167 | 332,372 | 410,082 | 1,144,890 |

| Net Worth | 347,438 | 628,141 | 743,509 | 1,559,852 |

| Lifetime Earnings | 921,198 | 1,706,600 | 1,849,256 | 2,362,983 |

Table 4.

Share of total assets held in each asset type for households aged 65–69 in 2010 by level of education and marital status

| Asset Category | < High School |

High School |

Some College |

College or More |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Households | ||||

| Financial Assets | 8.2 | 11.2 | 13.9 | 22.7 |

| Non-Mortgage Debt | −0.9 | −1.1 | −1.1 | −0.2 |

| Home Equity (primary | 18.0 | 19.3 | 18.0 | 16.2 |

| Home Equity (second home) | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.4 |

| Other Real Estate | 5.1 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 7.2 |

| Business Assets | 4.0 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 4.5 |

| Personal Retirement | 4.0 | 11.3 | 13.4 | 19.7 |

| - IRAs & Keoghs | 3.3 | 7.9 | 10.0 | 12.1 |

| − 401(k)s and Similar Plans | 0.7 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 7.5 |

| Social Security | 49.8 | 36.3 | 32.1 | 15.6 |

| Defined Benefit Pension | 9.6 | 10.8 | 12.7 | 11.0 |

| Non-Annuity Net Worth | 40.6 | 52.9 | 55.2 | 73.4 |

| Net Worth | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

2.5 The Less Educated Save Less, Given Lifetime Earnings

Asset balances can be decomposed into two components: one is lifetime earnings (LE) and the other is the propensity to save out of lifetime earnings (PS). That the less educated earn less over their lifetimes is well known. Perhaps not so well known is that, given lifetime earnings, those with less education save substantially less than those with more education.

Table 5 shows the ratio of mean total assets to mean lifetime earnings by lifetime earnings decile for the four levels of education that we use throughout the analysis.4 The table shows that (with only one exception) at each level of lifetime earnings the ratio of mean assets to mean lifetime earnings increases systematically with the level of education. Averaged over all lifetime earnings deciles, the ratios are 0.16, 0.18, 0.25, and 0.40 respectively for those with less than a high school degree, with a high school degree, with some college, and with a college degree or more. We refer to the ratio of assets to lifetime earnings as the propensity to save. The unusual values for the lowest earnings decile are likely due to large assets of persons whose earnings may not be covered by Social Security and thus have no or low reported Social Security earnings.

Table 5.

Ratio of mean assets to mean lifetime earnings, by lifetime earnings decile and by level of education

| Lifetime earnings decile |

Less than HS |

GED or HS graduate |

Some college |

College or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.71 | 2.27 |

| 2 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.80 |

| 3 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.51 |

| 4 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.39 |

| 5 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.31 |

| 6 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.37 |

| 7 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.38 |

| 8 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.41 |

| 9 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.41 |

| 10 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.36 |

| all | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.40 |

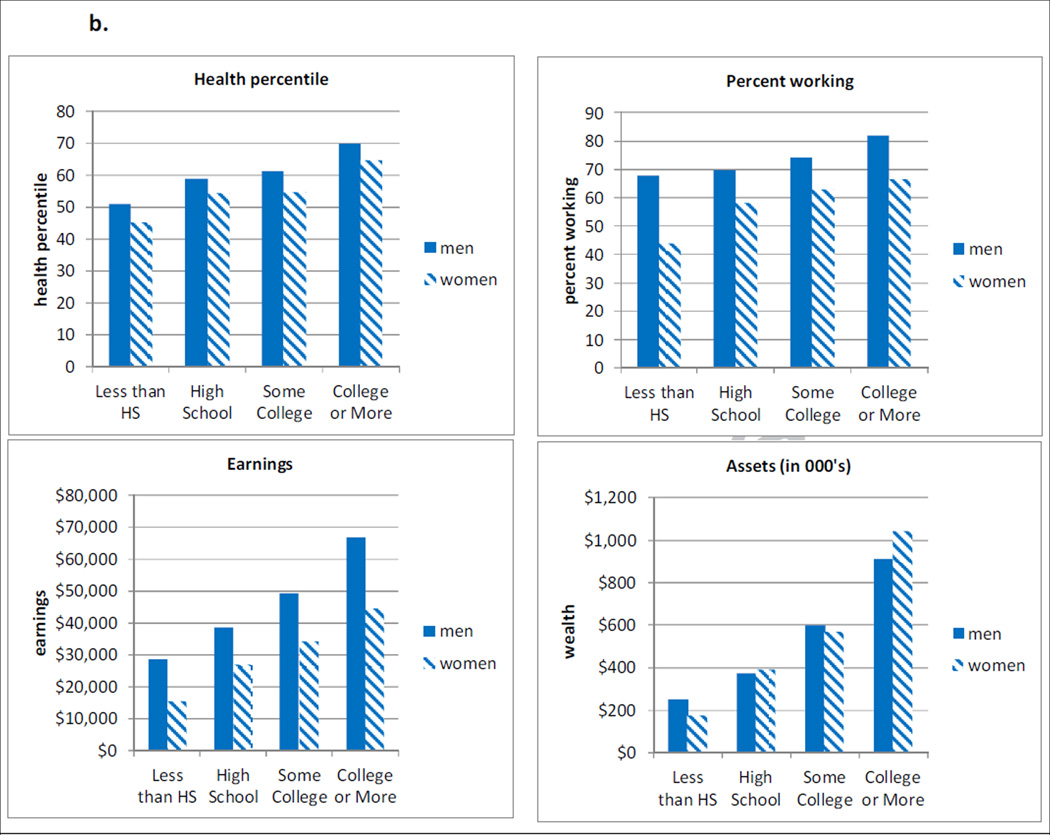

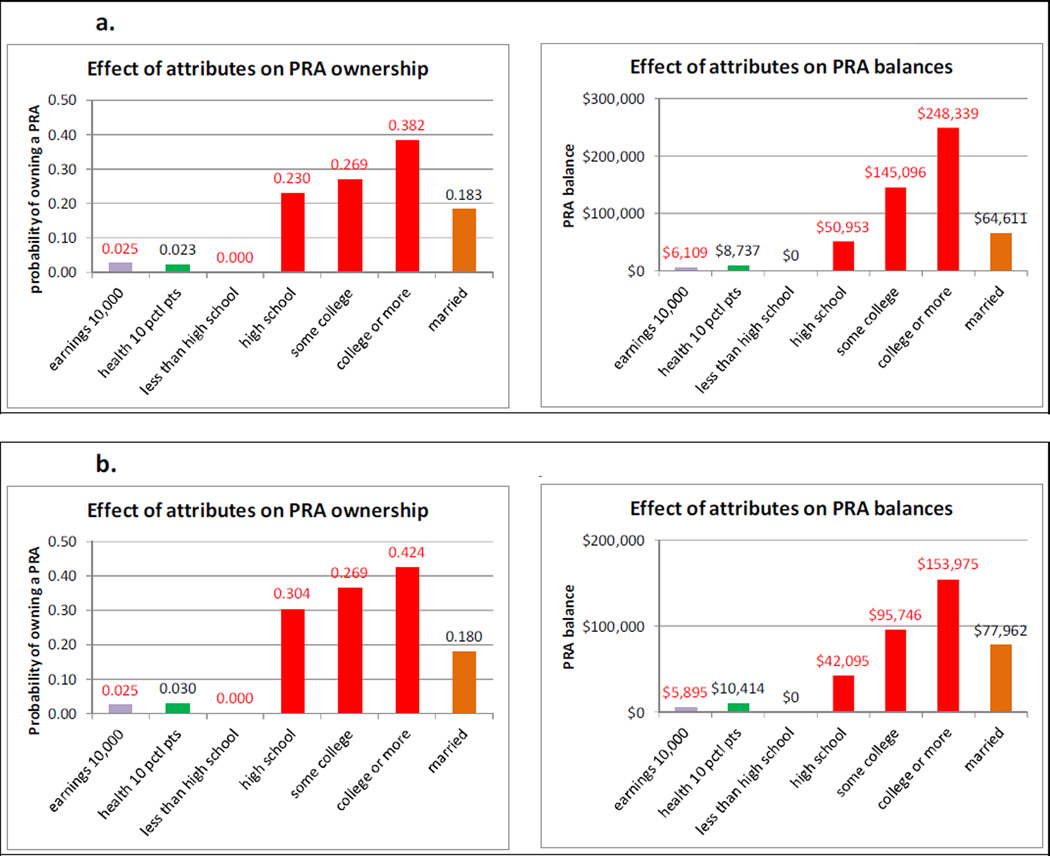

2.6 Personal Retirement Account (PRA) Ownership and Account Balances

Figure 2a (males) and 2b (females) are reproduced from Poterba, Venti, and Wise (2013b). The figures summarize the relationship between earnings, health, marital status, and education on the one hand, and PRA ownership (left panel) and PRA account balances (right panel).5 Note that these figures pertain to PRA assets only and earnings in the figures pertain to earning in the prior wave. The most striking result is the strong relationship between PRA ownership and education, controlling for earnings. For example, for men, the increase in the probability of PRA ownership associated with having a high school degree – compared to less than a high school degree – is over nine times as great as the increase associated with a $10,000 increment in earnings and ten times as great as the increase associated with a 10 percentile point increase in health. The effect of a college degree (relative to less than a high school degree) is over 15 times as large as the increase associated with a $10,000 increment in earnings and almost 17 times as great as a ten percentile point increase in health.

Figure 2.

a. Effect of attributes on PRA ownership and PRA balances, males

b. Effect of attributes on PRA ownership and PRA balances, females

Controlling for earnings, the association between education and the PRA balance is also very large. That is, it is not just higher earnings that education delivers; among those with the same level of earnings, those with more education also save more, as is also highlighted in Table 5.

While a $10,000 increment in earnings is associated with about a $6,000 increment is the PRA balance, the effect of education ranges from about $51,000 for a high school degree (relative to less than a high school degree) to almost $250,000 for a college degree or more (relative to less than a high school degree). For both PRA ownership and the PRA balance given ownership, the relationship between these outcomes and a ten percentage point increase in health is approximately equivalent to the effect of a $10,000 increase in earnings. Men who are married are also substantially more likely than single men to have a PRA and to have larger PRA balances given ownership. The results for women are very similar to the results for men.

3. Disability Insurance Participation

The analysis pertains to persons between the ages of 50 and 62. We exclude persons over the age of 62 because of eligibility for early Social Security benefits at that age. The analysis is based on the 1996 to 2010 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). There are approximately two years between each wave of the HRS. In each wave we include only those persons who have not previously received DI. We determine (by using the date benefits were first received) whether a person is a first-time recipient of DI benefits over a two-year period. An important consideration is that DI benefits cannot commence until at least five months after the disability onset.6 This waiting period means that each pathway variable must be measured at least five months prior to the date at which DI is initially received.7 Table 6 shows summary data by age of the first receipt of DI for all HRS respondents who ever received DI over the 1996 to 2010 period. The percent receiving benefits is lowest at ages 50 to 53; between ages 54 and 61 the percent is larger and fairly uniform by age.

Table 6.

Age of first receipt of DI for all persons who ever received DI

| Age | percent | cumulative |

|---|---|---|

| <50 | 26.4 | 26.4 |

| 50 | 3.7 | 30.1 |

| 51 | 3.9 | 34.0 |

| 52 | 4.5 | 38.5 |

| 53 | 4.3 | 42.8 |

| 54 | 6.1 | 48.8 |

| 55 | 5.1 | 53.9 |

| 56 | 5.2 | 59.1 |

| 57 | 5.7 | 64.8 |

| 58 | 6.0 | 70.8 |

| 59 | 5.6 | 76.4 |

| 60 | 5.6 | 82.0 |

| 61 | 5.6 | 87.7 |

| >61 | 12.3 | 100.0 |

We emphasize again that education has both direct and indirect effects on DI participation choices. Education may affect DI decisions indirectly by affecting an individual’s health, assets, employment status, or earnings capacity. Education may also have effects on DI choices that do not operate through any of the four pathways we describe; we label this the “direct” effect of education.8

3.1 Estimation of the Relationship between Education and DI

We estimate three probit specifications to understand the relationship between education and DI participation. The first specification is simply the relationship between DI participation and the level of education, given by:

| (1) |

Here LHS represent less than a high school degree, HS represent high school degree (or GED equivalent), SC represents some college, and CM represents a college degree or more. The second specification is the relationship between DI participation and each of the four pathways without controlling for education, given by:

| (2) |

In this specification the “employment” pathway is represented by two variables: E1 indicates whether the respondent was employed and E2 represents years since the respondent was last employed. The second employment variable is included so that whether a person was employed is distinguished from being out of the labor force for a long period of time. Also, H represents health, W represents weekly earnings (in $1,000) if employed, and A represents non-annuity assets. Employment, earnings, health, and assets are obtained from the most recent HRS wave that is at least one year prior to the date DI participation is observed. The third specification includes both the pathway effects and indicator variables for level of education which are intended to capture the direct effect of education not accounted for by the pathway variables and is given by:

| (3) |

The effect of education through the pathways in specification (2), for example, can be obtained from the following decomposition:9

| (4) |

where, for example, is the estimated marginal effect of H from the probit model (p̃1) and is the change in health associated with different levels of education. For this analysis the term is approximated by the difference in health between those without a high school degree and those with a college degree or more. Thus the effect of education on DI through the health pathway is given by . The effect of education through each of the other pathway is calculated analogously.

3.2 Estimated Marginal Effects for the Three Specifications

Table 7 shows the estimates (marginal effects) for the three specifications described above. The estimates for specification 1 simply show the total marginal effect of each level of education on the probability of initial DI participation. Men with a college degree or more are 2.23 percentage points less likely than those with less than a high school degree receive DI between waves of the HRS. This is a large effect compared to the mean actual probability of DI participation for men with less than a high school degree of 2.98 percent. Women with a college degree or more are 1.97 percentage points less likely to receive DI than women with less than a high school degree, again a large effect compared to the mean actual probability of DI participation for women with less than a high school degree of 2.17 percent. We sometimes refer to the total “education effect” as 2.23 percent for men and 1.97 percent for women.

Table 7.

Probit marginal effects for the probability of receipt of DI benefits for persons who did not receive DI benefits in the previous wave, age 50 to 62, by gender, three specifications.

| Specification 1. Education Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| variable | Men | Women | ||

| Estimate | z | Estimate | z | |

| HS | −0.0049 | −1.21 | −0.0014 | −0.42 |

| Some college | −0.0155 | −3.30 | −0.0059 | −1.56 |

| College or more | −0.0223 | −4.42 | −0.01974 | −4.08 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0329 | 0.0187 | ||

| Specification 2. Pathway variables only | ||||

| Health | −0.0004 | −6.11 | −0.0006 | −9.00 |

| Not employed | 0.0141 | 3.23 | 0.0065 | 2.34 |

| Years since last job | −0.0039 | −3.59 | −0.0017 | −3.75 |

| Weekly earnings ($1,000’s) | −0.0047 | −1.83 | 0.0004 | 0.75 |

| Assets ($10,000’s) | −0.0001 | −2.44 | −0.0001 | −2.00 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1075 | 0.1261 | ||

| Specification 3. Pathway variables and education | ||||

| Health | −0.0004 | −5.88 | −0.0005 | −9.00 |

| Not employed | 0.0145 | 3.32 | 0.0067 | 2.32 |

| Years since last job | −0.0039 | −3.57 | −0.0017 | −3.74 |

| Weekly earnings ($1,000’s) | −0.0033 | −1.30 | 0.0007 | 1.51 |

| Assets ($10,000’s) | −0.0001 | −1.88 | 0.0000 | −1.50 |

| High school | −0.0023 | −0.58 | 0.0046 | 1.26 |

| Some college | −0.0110 | −2.36 | 0.0026 | 0.64 |

| College or more | −0.0114 | −2.20 | −0.0062 | −1.20 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1182 | 0.1316 | ||

Specification 2 shows the marginal effects of each of the pathway variables without controlling for education. This specification allocates all of the effect of education on DI participation to the pathway variables. For both men and women, all of the pathway variables are statistically significant with the exception of weekly earnings.10 Most of the pathway variables have the expected sign: better health, higher wealth, higher earnings, and employment in the previous wave all reduce the probability of receiving DI benefits. Specification 3 includes the pathway variables as well as the education indicators to capture the direct effect of education that does not operate through the pathway variables. This specification minimizes the proportion of the education effect on DI that is captured by pathway variables. The top panel under this specification shows the estimated marginal effect of each pathway variable on DI participation. The bottom panel shows the (direct) effect of education controlling for the pathway variables. Note that for women, after controlling for the effect of the pathway variables, the estimated additional direct effect of education on DI participation is not statistically significant. For men, the direct effect of education is statistically significant for two of the three education levels.

3.3 Pathway and Direct Effects of Education

Table 8 shows the mean values for each of the pathway variables and the difference between the means of those with less than a high school education and of those with a college degree or more. The differences in the pathway variable means are substantial for each of the pathway variables.

Table 8.

Means of variables by level of education

| Level of education | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| less than high school |

high school degree |

some college |

college or more |

Difference college+ minus < HS) |

|

| Health | |||||

| men | 61.0 | 63.8 | 65.6 | 74.9 | 13.9 |

| women | 48.1 | 58.7 | 62.0 | 68.2 | 20.1 |

| Percent not employed | |||||

| Men | 19.1 | 15.3 | 14.0 | 8.7 | −10.4 |

| women | 49.1 | 27.5 | 23.1 | 17.6 | −31.5 |

| Years since last job | |||||

| men | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.21 | −0.44 |

| women | 2.69 | 1.73 | 1.44 | 1.24 | −1.45 |

| Weekly earnings | |||||

| Men | $531 | $759 | $952 | $1,708 | $1,177 |

| women | $212 | $384 | $531 | $931 | $719 |

| Assets | |||||

| Men | $195,837 | $339,274 | $468,496 | $903,119 | $707,282 |

| women | $193,817 | $357,286 | $532,727 | $885,248 | $691,431 |

We estimate the effect of education on DI participation through each of the pathways using the decomposition described above. The effect of education E through health H, for example, is given by: . Here dI / dH is the estimated marginal effect reported in Table 7 and (HCollege − H<HS) is obtained from the last column of Table 8. Thus for specification 2 the pathway effect for health is −0.0004 × 13.9 = −0.0053 for men. This implies that the effect of education through the health pathway accounts for about one half of one percent of the overall difference in DI participation rates between persons with a college degree or more and persons with less than a high school degree.

These pathway effects are shown in Table 9a. For specification 2, the sum of the pathway effects is about 1.7 percent for men and 1.4 percent for women. Based on specification 3, the sum of pathway effects is about 1.3 percent for men and for women. Recall that in specification 3 in Table 7 the estimated marginal effects of the education variables are not statistically significant for women. Moreover, the results in Table 9a show that for women there is only a small reduction in the sum of the pathway effects when education is included (specification 3) compared to the specification without education (specification 2).

Table 9.

| a. Estimates of the effect of education on the probability of initial DI claim through each pathway, by model specification and gender. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model without education dummies (specification 2) |

Model with Education dummies (specification 3) |

|||

| Pathways | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| Health | −0.0053 | −0.0110 | −0.0052 | −0.0109 |

| Not Employed | −0.0014 | −0.0020 | −0.0015 | −0.0021 |

| Years since Last Job | 0.0017 | 0.0024 | 0.0017 | 0.0025 |

| Weekly Earnings | −0.0055 | 0.0003 | −0.0039 | 0.0005 |

| Assets | −0.0062 | −0.0041 | −0.0043 | −0.0030 |

| Sum pathway effects | −0.0168 | −0.0144 | −0.0131 | −0.0131 |

| Total effect of education from model with educ dummies only |

−0.0223 | −0.0197 | −0.0223 | −0.0197 |

| b. Percent of the total effect of education on initial DI participation through each pathway and the direct non-pathway effect, by model specification and gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model without education dummies (specification 2) |

Model with education dummies (specification 3) |

|||

| Pathways | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| Health | 23.9% | 56.0% | 23.1% | 55.4% |

| Not Employed | 6.5% | 10.3% | 6.7% | 10.6% |

| Years since Last Job | −7.6% | −12.4% | −7.6% | −12.5% |

| Weekly Earnings | 24.6% | −1.5% | 17.4% | −2.4% |

| Assets | 27.9% | 20.7% | 19.1% | 15.2% |

| Sum of pathway effects | 75.3% | 73.2% | 58.7% | 66.4% |

| Non-pathway direct education effect | 24.7% | 26.8% | 41.3% | 33.6% |

| Total effect of education | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Note: Bold indicates significant at 10% level or better (for included pathway effects).

A key finding is that for both men and women few of the estimated coefficients on the pathway variables estimated in specification 2 are changed much when the education variables are added in specification 3. The estimated coefficients on health, not employed, and years since last job – that are estimated precisely in both specifications – are changed by less than 3 percent for both men and women. The estimated coefficients on weekly wage and assets for men are reduced by about 30 percent. The estimated coefficient on assets for women is reduced by about 27 percent. The coefficient of weekly wage for women is not statistically significant in either specification.

Table 9b shows the pathway and non-pathway effects as a percent of the total effect of education. In specification 2, the pathway effects account for 75.3 percent of the total education effect for men and 73.5 percent for women. In specification 3, the pathway effects account for 58.7 percent and 66.4 percent of the total effect of education for men and women respectively.11 In particular, as noted above, few of the pathway percentages change much when the direct effect of education is added to the specification. Although there is a rather close relationship between the level of education and the mean of pathway variables, the correlation between education and each of the pathway variables is not great enough to prevent precise estimation of both direct and indirect effects of education on DI participation.

3.4 Decomposition of the Wealth Effect

As noted earlier, the level of assets can be expressed as the product of two components – lifetime earnings (LE) and the propensity to save out of lifetime earnings (SP). We can use this decomposition to determine how much of the effect of education through wealth is due to the effect of education through lifetime earnings and how much is due to the effect of education through the saving propensity. This decomposition of the effect of education on DI participation is described by:

| (5) |

To calculate the LE and SP components, we need lifetime earnings, which we obtain from Social Security records that are available for 66 percent of our sample. The first four columns of Table 10 below show mean non-annuity assets, lifetime earnings, and the savings propensity by level of education for the subsample of respondents for whom we have linked earnings records.12

Table 10.

Means of variables by level of education

| Level of education | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | <HS | HS degree | Some college |

College or more | Difference (College+ minus < HS) |

Grand mean |

| Assets | ||||||

| men | $161,315 | $294,005 | $464,516 | $893,383 | $732,068 | $510,068 |

| women | $162,588 | $329,985 | $492,801 | $901,785 | $739,197 | $498,566 |

| Lifetime earnings | ||||||

| men | $1,037,393 | $1,805,977 | $1,939,314 | $2,264,646 | $1,227,253 | $1,890,004 |

| women | $1,004,416 | $1,744,898 | $1,879,923 | $2,261,382 | $1,256,966 | $1,825,705 |

| SP (ratio of means) | ||||||

| men | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.270 |

| women | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.273 |

The data in Table 10 can be used to calculate the decomposition in equation 5. The effects of education attributable to the LE and SP components for specifications 2 and 3 are shown in the Table 11 below. Notice first that for specification 2 the sum of the LE and SP components (that together comprise the effect of education on DI participation through the asset pathway) is −0.0069, but the estimated effect of education through the asset pathway in specification 2 is −0.0062 (from Table 9a), a difference of 9.9%. The difference is due primarily to the different samples used in the two calculations. For specification 3 the sum of the LE and SE components also differs from the estimated asset effect by 9.9%.

Table 11.

Comparison of decomposition esimates with specifications 2 and 3 estimates

| men | women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated values and estimates |

Percent of total |

Calculated values and estimates |

Percent of total |

|

| Using specification 2 coefficients | ||||

| LE component | −0.0029 | 42.2% | −0.0020 | 44.2% |

| SP component | −0.0040 | 57.8% | −0.0026 | 55.8% |

| Total | −0.0069 | −0.0046 | ||

| Specification 2 estimate | −0.0062 | −0.0041 | ||

| Difference decomposition vs. estimates |

9.9% | 10.9% | ||

| Using specification 3 coefficients | ||||

| LE component | −0.0020 | 42.2% | −0.0015 | 44.2% |

| SP component | −0.0027 | 57.8% | −0.0019 | 55.8% |

| Total | −0.0047 | −0.0034 | ||

| Specification 3 estimates | −0.0043 | −0.0030 | ||

| Difference decomposition vs. estimates |

9.9% | 10.9% | ||

For men, almost 58 percent of the effect of education through the asset pathway is due to the lower saving propensity of those with less education. About 42 percent is due to the lower lifetime earnings of those with the least education. The relative shares accounted for by the LE and SP components are the same for both specifications. For women, about 56 percent of the effect of education through the asset pathway is due to the lower saving propensity of those with the least education and about 44 percent to the lower lifetime earnings of those with the least education.13

3.5 The Changing Effect of Education over Time

We want to simulate the probability of DI participation for persons with less than a HS degree and those with a college degree or more for each HRS wave from 1996 and 2008. In doing this, we assume that the estimated marginal effect of each pathway variable shown in Table 7 remains constant over time. Thus any change in the relationship between education and DI participation will be due to changes in the pathway variables over time. To illustrate, Table 12 shows the effect of education through each pathway for persons in 1996 (top panel) and 2008 (bottom panel). The calculations are for men based on specification 3. The first two columns in each panel show mean values of each of the pathway variables for persons without a high school degree and for persons with a college degree or more. The third column shows the difference between those with less than a high school degree and those with a college degree or more. Notice that the difference between the college or more group and the less than high school group increased between 1996 and 2008 for three of the pathway variables: health, assets, and the likelihood of not being employed. The result is an increase in the effect for each of these pathway variables shown in the last column – the product of the marginal effect of each pathway variable shown in column 4 and the difference between levels of education shown in column 3 – and a 25 percent increase in the sum of the pathway effects, from −0.0107 in 1996 to 0.0138 in 2008. These data show that over the 12 year interval between 1996 and 2008, the likelihood of initial DI receipt has increased more for the less educated than for the highly educated. This divergence is due, in substantial part, to the widening gaps in health, assets, and employment between those with more and less education.

Table 12.

Pathway effects in 1996 and 2008, for men

| pathway | < HS | college or more |

difference | coefficient | pathway effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | |||||

| Health | 61.4 | 75.2 | 13.8 | −0.00037 | −0.0051 |

| not employed | 21.9 | 11.4 | −10.5 | 0.01447 | −0.0015 |

| years on last job | 0.76 | 0.25 | −0.51 | −0.00390 | 0.0020 |

| weekly earnings | $534 | $1,452 | $918 | −0.00329 | −0.0030 |

| assets | $167 | $671 | $504 | −0.00006 | −0.0030 |

| sum of pathway effects | −0.0107 | ||||

| 2008 | |||||

| health | 58.1 | 73.7 | 15.6 | −0.00037 | −0.0058 |

| not employed | 26.2 | 13.1 | −13.1 | 0.01447 | −0.0019 |

| years on last job | 0.61 | 0.24 | −0.37 | −0.00390 | 0.0014 |

| weekly earnings | $461 | $1,328 | $867 | −0.00329 | −0.0029 |

| assets | $197 | $975 | $778 | −0.00006 | −0.0047 |

| sum of pathway effects | −0.0138 | ||||

We can also use the parameter estimates to simulate the probability of initial receipt of DI by year for those with less than a HS education and those with a college degree or more. These simulated probabilities are shown in Table 13 for each of the HRS waves between 1996 and 2008. For men with less than a HS degree the probability of initially receiving DI is 3.1 percent in 1996 and 3.9 percent in 2008, an increase of over 27 percent. The probability of initial DI receipt was virtually unchanged for college graduates over this same period. The pattern for women is similar.

Table 13.

Simulated probability of initial receipt of DI in each year, for men and women

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | less than HS degree |

college or more |

less than HS degree |

college or more |

| 1996 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.005 |

| 1998 | 0.030 | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.005 |

| 2000 | 0.029 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.005 |

| 2002 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.006 |

| 2004 | 0.033 | 0.005 | 0.025 | 0.006 |

| 2006 | 0.035 | 0.006 | 0.026 | 0.006 |

| 2008 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.006 |

Note that these probabilities could be calculated directly from the data used in the estimation. There are, however, advantages and disadvantages to using simulated probabilities. The disadvantage is that we must assume that the estimated marginal effect of each pathway variable shown in Table 7 remains constant over time and thus that any change in the relationship between education and DI participation is due to changes in the pathway variables over time. An advantage of the simulation approach is that we can show the effect of changes over time in the levels of pathway variables shown in Table 12 for members of each education group. Another advantage of this approach is that the simulated probabilities are smoother and, unlike the probabilities calculated directly from the data, they are not subject to small sample variation. Perhaps the most important advantage is that the simulations demonstrate that if we had estimates of pathway variable differences like those in Table 12, from any source, we would be able to simulate DI participation in earlier years, even in the absence of data on DI participation, if we assume that the education effects that we estimate for the post-1996 period also apply to earlier years.

Finally, Table 14 shows the correspondence between the simulated DI probabilities and the actual probabilities aggregated over all education groups. With the exception of the initial receipt of DI at ages 51 and 52, the actual and the simulated values are quite close. The sample sizes for ages 51 and 52 are very small and a large fraction of the sample at these ages is composed of younger wives of men selected as HRS respondents. The estimated probabilities for these two ages lead to a small difference in the cumulated probabilities from age 50 to age 62. There is no difference in the cumulated probabilities from age 53 to age 62.

Table 14.

Fit: probability of initial receipt of DI at each age and cumulative over ages, actual and predicted

| Age | Probability of DI over two years* |

Cumulative from age 50** |

Cumulative from age 53** |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| predicted | actual | predicted | actual | predicted | actual | |

| 50 | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.015 | ||

| 51 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.018 | 0.017 | ||

| 52 | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.025 | 0.021 | ||

| 53 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.013 | 0.012 |

| 54 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.037 | 0.033 | 0.019 | 0.018 |

| 55 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.044 | 0.039 | 0.026 | 0.025 |

| 56 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.051 | 0.047 | 0.033 | 0.032 |

| 57 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.058 | 0.054 | 0.040 | 0.039 |

| 58 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.066 | 0.061 | 0.048 | 0.047 |

| 59 | 0.016 | 0.020 | 0.074 | 0.071 | 0.055 | 0.056 |

| 60 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.082 | 0.079 | 0.064 | 0.065 |

| 61 | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.091 | 0.089 | 0.072 | 0.074 |

| 62 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.098 | 0.095 | 0.080 | 0.080 |

The probability shown is the probability that a person will begin to receive DI over the next two years.

Calculation of the cumulative assumes that the probability of DI receipt over a one year peiod is half that of the two-year probability

4. Early Claiming of Social Security Benefits

4.1 Estimated Marginal Effects of Three Specifications

The analytic approach we follow to understand the relationship between education and early claiming of Social Security benefits is the same as the approach followed in the analysis of DI participation. We begin by estimating three specifications analogous to the specifications estimated for DI participation. The dependent variable is whether a person begins receiving early Social Security benefits (at ages of 62, 63, or 64). The pathway variables are measured in the most recent HRS wave prior to becoming eligible for early benefits at age 62.

The results are reported in Table 15. Specification 1, including only education indicator variables, shows that men with a college degree or more are over 25 percent less likely to claim Social Security benefits early than men with less than a high school degree. Women with a college degree or more are almost 27 percent less likely to claim Social Security benefits early than women with less than a high school degree. (The probabilities for men are 40.4 for those with a college education or more and 65.9 percent for those with less than a high school degree. The probabilities for women are 57.3 and 70.6 percent respectively.)

Table 15.

Probit marginal effects for the probability of early receipt of SS benefits, by gender, three specification

| Variable | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | z | Estimate | z | |

| Specification 1. Education only | ||||

| HS | −0.1010 | −2.60 | −0.0913 | −2.89 |

| Some college | −0.1385 | −3.34 | −0.1871 | −5.52 |

| College or more | −0.2536 | −6.58 | −0.2653 | −7.64 |

| Pseudo R2 | −0.0205 | −0.0241 | ||

| Specification 2. Pathway variables only | ||||

| Health | −0.0005 | −0.94 | −0.0016 | −4.18 |

| Not employed | −0.1266 | −3.82 | −0.0622 | −1.95 |

| Years since last job | −0.0445 | −11.20 | −0.0325 | −9.32 |

| Weekly earnings ($1,000 | −0.0394 | −2.32 | −0.1068 | −2.52 |

| Assets ($10,000’s) | −0.0003 | −1.99 | −0.0002 | −1.59 |

| Pseudo R2 | −0.1231 |

−0.1331 | ||

| Specification 3. Pathway variables and education | ||||

| Health | −0.0001 | −0.17 | −0.0014 | −3.54 |

| Not employed | −0.1302 | −4.00 | −0.0479 | −1.65 |

| Years since last job | −0.0434 | −11.18 | −0.0329 | −9.36 |

| Weekly earnings ($1,000 | −0.0338 | −2.15 | −0.0913 | −2.47 |

| Assets ($10,000’s) | −0.0001 | −0.82 | −0.0000 | −0.13 |

| HS | −0.0905 | −2.56 | −0.0601 | −2.02 |

| Some college | −0.1112 | −2.88 | −0.1143 | −3.50 |

| College or more | −0.1844 | −4.82 | −0.1807 | −4.95 |

| Pseudo R2 | −0.1331 | −0.1437 | ||

Data are from the 1998–2010 waves of the HRS. Pathway variables are from last wave before age 62

Specification 2 includes only pathway variables and thus assumes that all of the influence of education on early retirement is through the pathway variables. Perhaps most striking is that for men, the effect of health on early retirement is not statistically significant. The estimated coefficient on health for women is much larger than for men and highly significant.

Specification 3 allows education to influence retirement through the pathway variables, but also includes education indicators to capture the direct effect of education not accounted for by the pathway variables. This specification minimizes the proportion of the education effect on early claiming that is captured by the pathway variables. The top panel under this specification shows the estimated marginal effect of each pathway variable on early claiming. The bottom panel shows the (direct) effect of education controlling for the pathway variables.

Three results stand out. First, the direct effect of education is statistically significant and large (about 18 percentage points between the highest and lowest levels of education) for both men and women. The direct effect of education on the early claiming of Social Security benefits may arise if, for example, persons with more education are in occupations that provide more job satisfaction or are in occupations that are less physically demanding or are more attached to their jobs than those with less education.

Second, despite the large and significant direct effect of education, few of the estimated coefficients on the pathway variables change much when the education variables are added in specification 3, and most of the coefficients that change substantially were not statistically significant in specification 2.

Third, when the direct effect of education is added in specification 3, the small estimated effect of assets on the early claiming of Social Security benefits in specification 2 is essentially zero in specification 3. The estimated effect of assets is likely to be biased downward because of error in the measurement of assets. However, experimentation with different approaches to trim asset “outliers” does not yield large or more precise estimates of the effect of assets on early claiming.

4.2 Pathway and Direct Effects of Education

Table 16 shows the mean values of the pathway variables by level of education for both men and women observed in the wave just before the age of eligibility for early Social Security benefits. It is clear that there is a strong relationship between the mean level of education and each of the pathway variables, with the exception of years since last job for women. The differences in the means between those with a college degree or more and those with less than a high school degree are substantial.

Table 16.

Means of variables by level of education

| Level of education | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| less than high school |

high school degree |

some college |

college or more |

Difference College+ minus < HS) |

|

| Health | |||||

| men | 55.4 | 59.4 | 61.7 | 70.3 | 14.9 |

| women | 45.5 | 54.6 | 58.3 | 64.7 | 19.2 |

| Percent not employed | |||||

| men | 26.5 | 23.7 | 25.5 | 20 | −6.5 |

| women | 57.7 | 40.5 | 31.3 | 29.1 | −28.6 |

| Years since last job | |||||

| men | 2.34 | 2.52 | 2.08 | 1.75 | −0.59 |

| women | 3.17 | 3.39 | 2.83 | 3.13 | −0.04 |

| Weekly earnings | |||||

| men | $506 | $625 | $781 | $1,279 | $774 |

| women | $179 | $274 | $425 | $660 | $481 |

| Assets | |||||

| men | $209,756 | $409,913 | $616,562 | $1,023,354 | $813,598 |

| women | $228,582 | $431,038 | $620,725 | $962,932 | $734,350 |

Note: Data are from the 1998 – 2010 waves of the HRS. Pathway variables are from last wave before age 62

Table 17a shows estimates of the effect of education through each of the pathway variables and the sum of these pathway effects for specifications 2 and 3. To estimate the effect of education through each of the pathways, we follow the same approach we used in analyzing DI participation. Recall that the effect of education E on the early claiming of Social Security benefits (SS) through health H, for example, is given by: . Here dSS / dH is the estimated marginal effect reported in Table 3–1 and (HCollege − H<HS) is obtained from the last column of Table 16.

Table 17.

| a. Estimate of the effect of education on the probability of early receipt of SS benefits through each pathway, by model specification and gender. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway and education effects | Model without education dummies (specification 2) |

Mode with education dummies (specification 3) |

||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Pathways: | ||||

| Health | −0.0068 | −0.0315 | −0.0012 | −0.0267 |

| Not Employed | −0.0083 | −0.0177 | −0.0085 | −0.0137 |

| Years since Last Job | −0.0262 | −0.0011 | −0.0255 | −0.0011 |

| Weekly Earnings | −0.0305 | −0.0514 | −0.0261 | −0.0439 |

| Assets | −0.0216 | −0 0140 | −0.0088 | −0.0012 |

| Sum of pathway effects | −0.0933 | −0.1158 | −0.0702 | −0.0867 |

| Total effect of education from model with educ dummies only |

−0.2536 | −0.2653 | −0.2536 | −0.2653 |

| b. Percent of the total education effect on probability of early receipt of SS benefits accounted for by each pathway, by model specification and gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway and non-pathway | Model without education dummies (specification 2) |

Mode with education dummies (specification 3) |

||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Pathways: | ||||

| Health | 2.7% | 11.9% | 0.5% | 10.1% |

| Not Employed | 3.3% | 6.7% | 3.3% | 5.1% |

| Years since Last Job | 10.3% | 0.4% | 10.1% | 0.4% |

| Weekly Earnings | 12.0% | 19.4% | 10.3% | 16.6% |

| Assets | 8.5% | 5.3% | 3.5% | 0.5% |

| Sum of pathway effects | 36.8% | 43.6% | 27.7% | 32.7% |

| Non-pathway direct education effect | 63.2% | 56.4% | 72.3% | 67.3% |

| Total effect of education | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Note: Bold indicates significant at 10% level or better (for included pathway effects).

For both men and women the sum of the pathway effects is about 25 percent lower when education is added to the specification. In both specifications the sum of the pathway effects is somewhat greater for women than for men.

For the most part, however, the estimated effect of education through the pathway variables is not changed greatly when education is controlled for. For women the coefficients for three pathway variables – health, weekly earnings, and years since last job –change by 15 percent or less between specifications 2 and 3; for the not employed variable the reduction is 23 percent. For men the change for three pathways – weekly earnings, not employed, and years since last job – is 14 percent or less. For men the coefficient for health is reduced from −0.0068 to −0.0012 when education is added, but health is not an important determinant of the pathway effects in either specification. However, health is very significant for women. Comparing specifications 2 and 3 for men, the only other substantial change is the reduction in the coefficient for assets when education is added; the effect of assets is reduced from −0.0216 to −0.0088. For women, the asset pathway also becomes less important when the education variables are added; the effect of assets is reduced from −0.0140 to −0.0012.

In short, there is an important direct effect of education on the early claiming of Social Security benefits, but the addition of education has only a modest effect on the estimated effect of education through most of the pathway variables. The pathway variable most affected is the reduction in the estimated effect of wealth, and that effect is greatest for men. The effect through health is also reduced for men, but health is not an important component of the total pathway effect for men.

Table 17b is similar to Table 17a but shows the pathway and non-pathway effects as a percent of the total effect of education. In specification 2, the effect of education through the pathways accounts for 36.8 percent of the total effect of education for men and 43.6 percent for women. In specification 3, the pathway effects account for 27.7 percent and 32.7 percent of the total effect of education for men and women respectively. Note again, however, that most of the pathway percentages are changed only modestly when the direct effect of education is introduced – the same percentage changes as discussed above with respect to Table 17a. In particular, similar to the results for DI participation, although the data in Table 16 suggest a rather close relationship between the level of education and the mean of the pathway variables, the correlation between the individual pathway values and the level of education variables is not great enough to prevent us from estimating both the direct and indirect (pathway) effects of education on the early claiming of Social Security benefits.

The finding that assets have essentially no effect on the early claiming of Social Security at all when the direct effect of education is controlled for seems surprising. In most retirement models (Gustman and Steinmeier (1986), Stock and Wise (1990), Rust and Phelan (1997), and Blau (2008) for example) assets affect the retirement decision. Perhaps this is because these models do not include education in the specification. When education is controlled for in a regression analogue of the option value model, the effect of assets on retirement is insignificant. See for example Coile (2014), Banks, Emerson, Tetlow (2014), and other papers in Wise (forthcoming).

Finally, Table 18 shows actual and predicted proportion claiming early Social Security benefits by level of education. The fit is very close.

Table 18.

Probability of early Social Security receipt by gender and level of education, all years mean, actual and predicted

| Level of education | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Less than HS |

HS degree |

Some college |

College or more |

All | Diff: College+ - <HS |

| Actual | ||||||

| Men | 0.6587 | 0.5594 | 0.5213 | 0.4044 | 0.5170 | −0.2543 |

| Women | 0.7057 | 0.6186 | 0.5205 | 0.4390 | 0.5727 | −0.2667 |

| Predicted | ||||||

| Men | 0.6593 | 0.5594 | 0.5172 | 0.4013 | 0.5153 | −0.2580 |

| Women | 0.7035 | 0.6186 | 0.5204 | 0.4332 | 0.5712 | −0.2703 |

5. Summary and Discussion

The goal of this paper is to draw attention to the long lasting influence of education. To illustrate this influence we focus on the relationship between the level of education and two routes to early retirement – the Social Security Disability Insurance program (DI) and the early claiming of Social Security retirement benefits. These routes are followed disproportionately by those who are typically ill-prepared to work longer because of health or other reasons. Of men with less than a high school degree, 27 percent receive DI between the ages 50 and 62; of those with a college degree or more only 5 percent in this age range receive DI. Of men with less than a high school degree who are not on DI at age 62, 66 percent claim Social Security benefits before the normal retirement age; of those with a college degree or more, 40 percent take Social Security benefits early. The percentages are similar for women

For both routes to retirement we focus on four critical pathways – health, employment, earnings, and the accumulation of assets – through which education may indirectly influence DI and early retirement decisions. We emphasize that in addition to these indirect effects of education through the pathways, education may also have an additional direct effect on both routes to retirement that does not operate through the designated pathways. Both the direct and indirect effects are estimated. We emphasize that in this paper we view education as a marker for all that accompanies education; we do not attempt to identify the causal component of the relationship between education and either DI or the early claiming of Social Security benefits.

The analysis of DI participation considers the probability that a person between the ages of 50 and 62 first receives DI between the approximate 2-year intervals between waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) from 1996 to 2010. The early claiming of Social Security benefits is also based on HRS data, but considers whether a person not on DI at age 61 begins receiving early Social Security benefits (at the ages of 62, 63, or 64).

We find that the median simulated initial DI participation rate over a two-year HRS interval for men with less than a high school degree is 0.0196 and the median for men with a college degree or more is 0.0030, a 6.6 fold difference. The DI participation rate for women with less than a high school degree is 0.0136 and the median for women with a college degree or more is 0.0021, a 6.5 fold difference. Men with a college degree or more are over 25 percentage points less likely to claim Social Security benefits early than men with less than a high school degree. Women with a college degree or more are almost 27 percentage points less likely to claim Social Security benefits early than women with less than a high school degree.

One way to summarize key findings is by the proportion of the total effect of education that is accounted for by the influence of education through the pathways (indirect effect) and the proportion accounted for by the direct effect of education. These proportions are shown for DI (top panel) and early Social Security claiming (bottom panel) in the accompanying tabulation. Two sets of proportions are shown: those on the left pertain to a model specification that does not control for the level of education and those on the right control for the level of education. Essentially, these two sets of estimates reflect the upper and lower bounds of the effect of education through the pathway variables. These results highlight the importance of the indirect effect of education. For example, Table 1 shows that for both men and women education is strongly related to DI participation. For women, however, the estimates suggest that it is primarily the indirect effect of education that influences DI participation; controlling for the pathways – health, employment, wage, and assets – the direct effect of education is not statistically significant. Thus it is not only the level of education itself that matters but the relationship between education and the pathways, all important determinants of life satisfaction more broadly. The relative effect of education on DI through the pathways is somewhat less for men but still very important, and much less for early claiming of Social Security benefits for both men and women.

Percent of total effect of education accounted for by pathway effects and by the direct effect of education

| Without education levels |

With education levels |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Disability Insurance | ||||

| Pathway effects | 75.3% | 73.2% | 58.7% | 66.4% |

| Direct effect | 24.7% | 26.8% | 41.3% | 33.6% |

| Early Claiming of Social Security Benefits | ||||

| Pathway effects | 36.8% | 43.6% | 27.7% | 32.7% |

| Direct effect | 63.2% | 56.4% | 72.3% | 67.3% |

We emphasize two features of these estimates. First, the effect of education through the pathways is substantially larger for DI participation than for early Social Security claiming, whether education is controlled for or not. The estimates in the left panel suggest that the pathway variables account for 75.3 percent of the total effect of education on DI participation for men and 73.2 percent of the total effect for women. Comparable percentages for the early Social Security claiming decision are 36.8 percent and 43.6 percent. Estimates controlling for the level of education (right panel) also show that the effect of education through the pathways is also greater for DI than for early claiming. It is not clear to us why the effect of education should be larger for DI participation than for early Social Security claiming. This finding warrants additional research. Second, the percent accounted for by the pathway effects is lower when the direct effect of education is allowed for (by including education levels in the estimation specification). The smallest reduction is for DI participation for women − 73.2 to 66.6 percent. Indeed, the estimated direct education effects for women, on which this difference is based, are not significantly different from zero.

An important result is that for both DI and early claiming, few of the estimated coefficients on the pathway variables estimated in the specification without the direct effect of education (education levels) are changed much when the education variables are added to the specification. In particular, although the means of the pathway variables differ considerably by level of education, the correlation between education and each of the pathway variables is not great enough to prevent precise estimation of both direct and indirect effects of education on DI participation. The ability to precisely estimate both direct and indirect effects suggests that the estimated effect of changes in health, employment and earnings on both DI outcomes are largely independent of education, that is, the source of the change in each of the pathway variables – whether education or other factors – is irrelevant. The one exception is wealth, whose pathway effect is reduced when education is directly accounted for, and that effect is greatest for men.

Finally, we draw attention to the large direct effect of education on the early claiming of Social Security benefits together with two associated and perhaps unexpected findings. First, we find that health is not a significant determinant of early claiming for men but a very significant determinant for women. Second, perhaps most striking, we find that that assets have essentially no effect on the early claiming of Social Security benefits when the direct effect of education is controlled for, a finding that differs from estimates that do not include education in the specification. That is, the inclusion of education in the model reveals a large direct effect of education and a corresponding virtual elimination of the estimated effect of assets, commonly thought to be an important determinant of retirement, and an effect of health—also thought to be an important determinant of retirement—only for women.

We have estimated a large direct effect of education which suggests that education matters for DI outcomes, even after controlling for the pathways. What is the source of this direct effect? One possibility is that persons with more education are in occupations that are less physically demanding, that provide more job satisfaction, have higher levels of job attachment, or offer more opportunities for continued work at older ages. Although many features of jobs or occupations are picked up by the earnings and employment pathways, these pathways may not entirely capture the effect of job attributes such as job satisfaction or opportunities for work at older ages. Another possibility, emphasized by Campbell (2006), is that more educated persons make better financial decisions and thus better understand the benefits of late Social Security claiming. In sum, although we believe that the parsimonious specification we use provides an informative description of the importance of education on DI participation and on the early claiming of Social Security benefits, further exploration of the direct effect of education on retirement seems an important issue for future research.

The key findings of the paper seem robust to alternative presentations of the data. The effect of education on early retirement is huge. Most of the effect of education on DI participation is indirect through the effect of education on health, wealth, earnings and employment. Most of the effect of education on the early claiming of Social Security benefits is accounted for by the direct effect of education and not indirectly by way of the effect of education through the health, wealth, earnings, and employment pathways.

Finally, our focus on the effect of education on early retirement is one of many examples that could be used to illustrate the long reach of education.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by the Met Life Foundation through the Met Life Foundation Silver Scholar Award, administered by the Alliance for Aging Research, to David Wise. The research was also supported by the U.S. Social Security Administration through grant # RRC08098400-06-00 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Retirement Research Consortium, and by the National Institute on Aging, through grants #P01 AG005842 and #P30 AG012810. We have benefited from comments by James Poterba, by David Autor, and from comments by participants in the Workshop on Facilitating Longer Working Lives: Low-Skilled Workers and Education, held at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, London, in April 2014.

Appendix on Measuring Health

Our analysis depends critically on measuring health status. We use a health index that is based on respondent-reported health diagnoses, functional limitations, medical care usage, and other indicators of health contained in the HRS. We use the first principal component of the 27 indicators of health status that are shown in Appendix Table 1. The first principal component is the weighted average of the health indicators where the weights are chosen to maximize the proportion of the variance of the individual health indicators that can be explained by this weighted average. The variables in the table are ordered by the principal component loadings.

Appendix Table 1.

Health index weights (principal component loadings)

| Variable | Loading |

|---|---|

| Difficulty walking several blocks | 0.294 |

| Difficulty lift/carry | 0.277 |

| Difficulty push/pull | 0.272 |

| Difficulty with an ADL | 0.267 |

| Difficulty climbing stairs | 0.261 |

| Health problems limit work | 0.259 |

| Difficulty stoop/kneel/crouch | 0.257 |

| Self-reported health fair or poor | 0.255 |

| Difficulty getting up from chair | 0.248 |

| Difficulty reach/extend arms up | 0.210 |

| Health worse in previous period | 0.208 |

| Difficulty sitting two hours | 0.184 |

| Ever experience arthritis | 0.183 |

| Difficulty pick up a dime | 0.153 |

| Hospital stay | 0.148 |

| Ever experience heart problems | 0.146 |

| Home care | 0.144 |

| Back problems | 0.136 |

| Doctor visit | 0.134 |

| Ever experience psychological problems | 0.131 |

| Ever experience stroke | 0.125 |

| Ever experience high blood pressure | 0.120 |

| Ever experience lung disease | 0.120 |

| Ever experience diabetes | 0.107 |

| Nursing home stay | 0.069 |

| BMI at beginning of period | 0.065 |

| Ever experience cancer | 0.057 |

This index used here is identical to that used in Heiss, Venti and Wise (2014) and is an updated version of the index used in Poterba, Venti and Wise (2013a). Prior work has shown that separate estimates of the index for each wave of the HRS produce similar factor loadings, so this version of the index pools all waves. We have also combined men and women based on the similarity of factor loadings. We use data from all five HRS cohorts spanning the years 1994 to 2010 to estimate the principal component index.14 The estimated coefficients are used to predict a “raw” health score for each respondent. For presentation purposes we convert these raw scores into percentile scores for each respondent at each age.