Abstract

We report the first successful transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian cortical tissue into heavily irradiated tissues in a patient who had received sterilizing pelvic radiotherapy (54 Gy) and 40 weeks of intensive high-dose chemotherapy for the treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma 14 years earlier. Repeated transplantation procedures were required to obtain fully functional follicular development. Enlargement of the transplants over time and increase of the size of the uterus were demonstrated on sequential ultrasonographic examinations. Eggs of good quality that could be fertilized in vitro were obtained only after a substantial incremental increase of the amount of ovarian tissue transplanted. Single embryo replacement resulted in a normal pregnancy and the birth of a healthy child by cesarean section at full-term. No neonatal or maternal postoperative complications occurred. Women facing high-dose pelvic radiotherapy should not be systematically excluded from fertility preservation options, as is currently the trend.

Keywords: Cancer, chemotherapy, fertility preservation, iatrogenic ovarian failure, live birth, ovarian tissue cryopreservation, ovarian transplantation, pregnancy, survivorship, uterine irradiation

Introduction

Many cancer patients, particularly women, still do not receive adequate information on the impact of cancer treatment on reproductive capability 1. Difficulties and barriers have been discussed, such as the need for invasive procedures to retrieve eggs and tissues, but the fact that some methods, such as the freezing of ovarian tissue, are still considered experimental, limits women’s access to fertility preservation 2.

Here we report the first case of recovery of fertility after transplantation of frozen, banked ovarian tissue in a woman who received sterilizing pelvic radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy. Successful transplantation into pelvic tissues that have been irradiated has not been described. More importantly, as irradiation of the uterus is regarded as a definitive factor causing sterility, it is likely that women planned for similar treatments to ours, are systematically excluded from programs for fertility preservation.

Case report

In December 1999, a previously healthy 23-year-old woman presented with a locally advanced tumor of the sacrum, which was identified by needle biopsy as Ewing’s sarcoma. The treatment proposed for the patient (Italian–Scandinavian treatment protocol ISG/SSG III, activated in June 1999) included 40 weeks of intensive chemotherapy between January and September 2000 and concomitant hyperfractionated radiotherapy, 1.5 Gy twice daily, 5 days a week for 4 weeks to a planning target volume of the minor pelvis and consecutive boosts to a clinical target volume of the sacrum, leading to a pelvic total dose of 54 Gy. The treatment protocol offered to the patient was regarded as potentially curative, as the tumor appeared to be nonmetastatic in scintigraphy scans.

At the time of planning the treatment, the patient was informed of the very high probability that she would become sterile as a result of the high doses of both chemotherapy and pelvic radiotherapy. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation was proposed for fertility preservation. As no children had been born after re-transplantation of ovarian tissue in 1999, the likelihood of recovering fertility after those procedures was unknown. This information was provided in a clear way to the patient. Unilateral oophorectomy was proposed, because of the high probability of ovarian damage. The potentially negative effects of radiotherapy on the uterus were also discussed. A left unilateral oophorectomy was performed at the time of laparoscopic colostomy, indicated because of tumor invasion of the sacral nerves compromising intestinal transit. The cortical ovarian tissue collected was cryopreserved in 97 pieces of 1 × 3 × 5 mm. Slow freezing using propanediol–sucrose for cryopreservation was used, as previously reported 3. Complete tumor regression was confirmed on scintigraphy scans after treatment, and clinical follow up was suspended after 10 years of recurrence-free survival The patient developed permanent ovarian failure after cancer treatment and she requested re-transplantation at age 31 years. Serum hormone concentrations confirmed menopausal status.

The safety of the ovarian tissue was evaluated by histology in random samples accounting for approximately 15% of the tissue collected. Absence of malignant cells was demonstrated in all samples. All tissue components were well-preserved after thawing and follicles were present at all developmental stages.

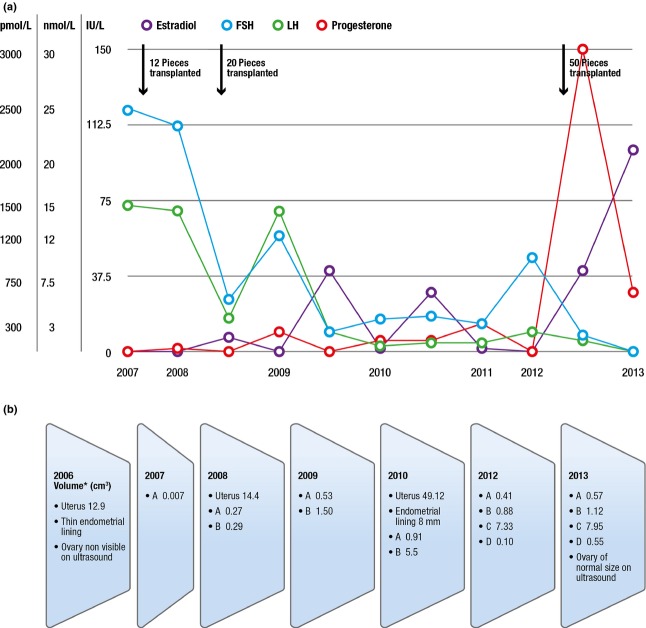

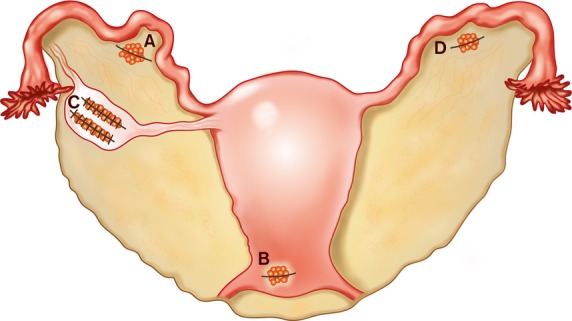

Three ovarian tissue transplantation procedures at four locations were required to increase ovarian reserve and to support competent oocyte recruitment. The first and second transplants performed in 2007 and 2008 repositioned approximately 10 and 25% of cortical tissue, respectively (Figure1). During the surgical interventions, the right ovary was observed and described as atrophic, resembling a streak gonad. Although follicular development was observed on ultrasound scans several times in the transplants since the fifth month after surgery, and enlargement of the transplants and increase of the size of the uterus were also documented, gonadotropin levels declined only temporarily (Figure2a,b). Six in vitro fertilization (IVF) attempts between 2008 and 2011 failed because of a low response to hormonal stimulation, failure in retrieving any eggs, or the embryos obtained after intracytoplasmic sperm injection not being morphologically of good quality. Climacteric symptoms reappeared in 2012 with persistently high gonadotropin concentrations. Hence, a third transplantation was planned aiming at depositing a larger amount of ovarian tissue (50% of the collected tissue). Most of the cortical pieces were transplanted at the orthotopic location into two deep pockets made by scalpel incisions in the remaining right ovary 4 (Figure1). The ovarian function promptly recovered, and spontaneous ovulation was demonstrated for the first time (Figure2a), with confirmation of a postovulatory corpus luteum in the orthotopic transplant by ultrasonography.

Figure 1.

Anatomical positioning of ovarian cortical tissue pieces at four locations. Transplantation procedures were performed in 2007, 2008 and 2012. Position A Twelve cortical pieces transplanted in a peritoneal pocket in the mesosalpinx (2007), 10 pieces (2008), 10 pieces (2012); Position B 10 pieces transplanted subperitoneally in the lower abdominal wall (2008); Position C 24 pieces transplanted into two deep ovarian cortical-medullar incisions (2012); and Position D 15 pieces transplanted in a peritoneal pocket in the left mesosalpinx (2012).

Figure 2.

Follow up of ovarian transplants over time. (a) Serum hormone concentrations: estradiol (pmol/L), progesterone (nmol/L), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH; IU/L), luteinizing hormone (LH; IU/L). (b) Ultrasonographic findings, ovarian size, thickness of the endometrial lining, estimation of ovarian transplant volume at anatomical transplant positions (A, B, C, D; see Figure1) and volume of the uterus over time. The volume (cm3) was calculated according to the formula for ellipsoid bodies (width × depth × length × 0.52) 12.

Gonadotropin stimulation following spontaneous menstruation in March 2013 resulted in retrieval of three oocytes from the ortothopic ovarian transplant, and these were fertilized using intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Three embryos of good quality were obtained. Single embryo transfer was carried out and a pregnancy was achieved. Two supernumerary embryos obtained in this treatment were of morphological good quality and they were cryopreserved for possible treatment in the future.

The pregnancy evolved normally without signs of uterine growth restriction. A cesarean section was performed at full term (week 38). A healthy girl weighing 2970 g was born with Apgar scores of 9/1, 10/5 and 10/10 min, respectively. Intraoperative bleeding and postpartum uterine contraction were normal. The mother and the baby went home in good health 4 days after the delivery. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and all accompanying images.

Discussion

Restoration of ovarian function and follicular development after transplantation of thawed cryopreserved ovarian cortical tissue was first reported in 2000 5 and recovery of fertility and live births have been documented in 24 women in a period of over 12 years 6. In more than 50% of the cases, the pregnancies have occurred spontaneously, which is currently encouraging. Only in nine cases, similar to the one reported herein, were assisted reproductive technologies applying IVF to eggs aspirated from the ovarian transplants performed 6. As only six of those nine women presented with cancer at the time of ovarian tissue cryopreservation, the accumulated worldwide experience is still limited. Additionally, none of the women who have achieved pregnancy had received pelvic radiotherapy at doses that may compromise uterine function.

Successful transplantation of ovarian tissue is still demanding and hard to accomplish. An important problem limiting the efficacy is the recognized ischemic loss of over 50% of the primordial follicles contained in the graft. This occurs until neo-angiogenesis and revascularization of the graft are restored 7,8. Accelerated follicle activation and discrepancy between granulosa cell and oocyte maturation have also been suggested as further causes of follicle loss after transplantation. Further research is needed to optimize the viability of ovarian transplants 7,8.

The persistent deleterious effects of radiation on soft tissues make transplantation into previously irradiated pelvic structures even more difficult. An irradiation dose >40 Gy is regarded as potentially sterilizing both to the ovaries and to the uterus 9,10. For that reason, women facing treatments including pelvic radiotherapy at doses higher than 40 Gy are usually excluded from fertility preservation programs, because the uterus is unlikely to later support a pregnancy. By the medical means available today the sterility caused by irradiation of the uterus is not treatable. Our present first successful case is very encouraging in this respect.

Re-transplantation of ovarian tissue that had been cryopreserved before cancer treatment has the potential risk of re-seeding cancer cells within the tissue pieces at the time of re-transplantation. Therefore, it is essential to determine the safety of the tissue in each case. With regard to Ewing’s sarcoma, it is known that this tumor type and other sarcomas rarely metastasize to the ovaries 11. It is noteworthy that in all published studies only a minor proportion of the collected ovarian tissue (one or two pieces) has been investigated 5–7. More importantly, no method can be considered as a reference standard today, because all the methods are destructive and so the evaluated tissue cannot be subsequently used for transplantation. Therefore, the tissue being grafted cannot be checked for residual disease. Facing this clinical challenge, we decided to devote a large amount of the cryopreserved tissue, about 15% (15 random pieces), to the evaluation of tissue safety by histology.

Our approach of transferring one single embryo is the norm in our IVF program, but was further stressed by the concern of uterine restriction as a consequence of irradiation exposure. As illustrated in Figure2b, a noteworthy increase of the size of the uterus was observed during 6 years, as demonstrated on sequential ultrasonographic uterine volume estimations. Enlargement of the transplants over time was also documented but eggs and embryos of good quality could only be obtained after a substantial increment of ovarian tissue transplanted. The final endometrial lining achieved in response to hormonal stimulation during the fertility treatment that resulted in the pregnancy was also within optimal scores to support embryo implantation, demonstrating a high potential of the uterus to recover.

Our case demonstrates that an ovary after high-dose irradiation may sustain transplantation and the growth of ovarian follicles within cortical grafts, and that a gravely irradiated uterus may support pregnancy until full term. Notably, repeated transplants may be required in patients who undergo high-dose pelvic radiotherapy. The orthotopic site should probably be preferred. Our case underscores the role of providing information and access to fertilization programs even for women for whom high-dose pelvic irradiation is planned.

Funding

The Swedish Research Council, The Swedish Society for Medical Research (SSMF), The Swedish Society of Medicine, Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet supplied research grants.

Acknowledgments

We thank the personnel of the oncology clinic, pathology and reproductive medicine of Karolinska University Hospital, in particular Jonas Harlin, Elisabet Lidbrink, Jessika Lundmark, Eija Matilainen, Lena Möller, Inga-Lill Persson, Marie Klinta Svensson, Karin Persdotter Eberg, Annett Johansson, Christina Scherman Pukk, Malin Broberg, Annika Abu Esba, Yvonne Lann and Stefan Cajander.

Glossary

- IVF

in vitro fertilization

References

- Armuand GM, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Wettergren L, Ahlgren J, Enblad G, Hoglund M, et al. Sex differences in fertility-related information received by young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2147–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, Brennan L, Magdalinski AJ, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2500–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta O, Silye R, Krausz T, Abir R, Margara R, Trew G, et al. Cryopreservation of human ovarian tissue using dimethylsulphoxide and propanediol-sucrose as cryoprotectants. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1268–72. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen CY, Rosendahl M, Byskov AG, Loft A, Ottosen C, Dueholm M, et al. Two successful pregnancies following autotransplantation of frozen/thawed ovarian tissue. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2266–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oktay K, Karlikaya G. Ovarian function after transplantation of frozen, banked autologous ovarian tissue. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnez J, Dolmans MM, Pellicer A, Diaz-Garcia C, Sanchez Serrano M, Schmidt KT, et al. Restoration of ovarian activity and pregnancy after transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue: a review of 60 cases of reimplantation. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1503–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Oktay K. Recent advances in oocyte and ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:391–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eyck AS, Jordan BF, Gallez B, Heilier JF, Van Langendonckt A, Donnez J. Electron paramagnetic resonance as a tool to evaluate human ovarian tissue reoxygenation after xenografting. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:374–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HO, Wallace WH. Impact of cancer treatment on uterine function. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;34:64–8. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Oktay K. Fertility preservation medicine: options for young adults and children with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:390–6. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181dce339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HC, Shulman SC, Olson T, Ricketts R, Oskouei S, Shehata BM. Unusual presentation of metastatic Ewing sarcoma to the ovary in a 13-year-old: a case report and review. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2012;31:159–63. doi: 10.3109/15513815.2012.659379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andolf E, Jorgensen C, Svalenius E, Sunden B. Ultrasound measurement of the ovarian volume. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66:387–9. doi: 10.3109/00016348709022039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]