Abstract

Progestins induce lipid accumulation in progesterone receptor (PR)-positive breast cancer cells. We speculated that progestin-induced alterations in lipid biology confer resistance to chemotherapy. To examine the biology of lipid loaded breast cancer cells, we used a model of progestin-induced lipid synthesis. T47D (PR-positive) and MDA-MB-231(PR-negative) cell lines were used to study progestin response. Oil red O staining of T47D cells treated with progestin showed lipid droplet formation was PR dependent, glucose dependent and reduced sensitivity to docetaxel. This protection was not observed in PR-negative MDA-MB-231 cells. Progestin treatment induced stearoyl CoA desaturase-1 (SCD-1) enzyme expression and chemical inhibition of SCD-1 diminished lipid droplets and cell viability, suggesting the importance of lipid stores in cancer cell survival. Gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy analysis of phospholipids from progestin-treated T47D cells revealed an increase in unsaturated fatty acids, with oleic acid as most abundant. Cells surviving docetaxel treatment also contained more oleic acid in phospholipids, suggesting altered membrane fluidity as a potential mechanism of chemoresistance mediated in part by SCD-1. Lastly, intact docetaxel molecules were present within progestin induced lipid droplets, suggesting a protective quenching effect of intracellular lipid droplets. Our studies suggest the metabolic adaptations produced by progestin provide novel metabolic targets for future combinatorial therapies for progestin-responsive breast cancers.

Keywords: Progestin, metabolism, breast cancer, SCD-1, lipid droplets, docetaxel

1. Introduction

Although the Warburg effect has been recognized for over fifty years (WARBURG 1956), less understood are alterations in lipid metabolism and the rapid rates of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis of many tumors (Menendez et al., 2007). Lipid synthesis is an integrated result of genetic, epigenetic and environmental (lifestyle) factors that favor growth and survival of cancer cells. In fact, de novo fatty acid synthesis (lipogenesis) appears early in oncogenesis, expands as the cells become more malignant, promotes the transition from pre- and high-risk lesions to invasive cancer, and may account for >90% of triglycerides (TG) in tumor cells (Kuhajda 2006; Menendez et al., 2007). This lipid synthesis is intensified regardless of regulatory signals like circulating dietary lipids, which are preferentially used by normal cells. In normal cells, lipogenesis is observed during embryogenesis, lung development and in hormone-sensitive tissues like liver, endometrium and the lactating breast (Kusakabe et al., 2000). Little is known about the impact of these lipid changes in mediating proliferation and/or resistance of cancer cells to current therapies.

Sex steroids regulate proliferation and lipid accumulation in breast cancer cells (Chalbos et al., 1982; Judge et al., 1983). Although lipogenesis is a hallmark of most cancers, some breast cancer cells produce large amounts of lipids in response to the female hormone progesterone (Chalbos et al., 1984; Menendez et al., 2007). Progesterone and its analogues (progestins) are also implicated in weight gain (Kalkhoff 1982; Rochon et al., 2003; Shirling et al., 1981; Tuttle et al., 1974), diabetes (Meyer, III et al., 1985; Picard et al., 2002) and in breast cancer risk (Nelson et al., 2002; Rossouw et al., 2002). Estrogen plus progestin combined therapy is also associated with increased breast cancer mortality (Chlebowski et al., 2010), underscoring the effect of hormones on adverse outcomes in breast cancer. All these data suggest additional roles for progesterone when cancer develops, including the expansion of breast cancer progenitor cells (Horwitz et al., 2008). In fact, women of all ages have a transient increase in breast cancer risk associated with pregnancy, when progesterone levels are very high (Lyons et al., 2009; Schedin et al., 2009). The main intrinsic subtypes of breast tumors include: luminal estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR) positive and basal-like (negative for ER and PR) subtypes (Perou et al., 2000; Sorlie et al., 2001).

Breast cancer cell lines are valuable models because they reflect the spectrum of breast tumor subtypes (Neve et al., 2006). Seventy to eighty percent of breast tumors are luminal and express ER and/or PR (Keen et al., 2003), and PR are important biomarkers in breast tumors where they function as transcription factors when activated by progestins (for review see (Lange 2008)). Additional changes induced by progesterone, like metabolic changes, could underlie the increased breast cancer risk associated with progesterone use (Sartorius et al., 2005; Yager et al., 2006). Furthermore, progestin treatment of PR+ breast cancer cells has been implicated in chemoresistance (Ory et al., 2001) and cellular apoptotic signals (Moore et al., 2006). Among the most effective treatments for breast tumors is the taxane docetaxel, which inhibits microtubule formation. However, several studies show luminal breast tumors are resistant to chemotherapy (Badtke et al., 2012; Henderson et al., 2003; Schmidt et al., 2007).

Fatty acid synthase (FASN) is an enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of fatty acids from glucose, and its expression is increased in many epithelial cancers including breast cancer (Kuhajda 2006; Kusakabe et al., 2000). Progestins increase FASN in PR+ breast cancer cells (Chalbos et al., 1990) and FASN expression correlates with poor tumor prognosis (Menendez et al., 2007). Another enzyme involved in lipid synthesis is stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD-1), which generates monounsaturated palmitoleic and oleic acids which become part of the phospholipid bilayer and/or components of lipid droplets. Inhibition of SCD-1 in breast cancer cells blocks lipid synthesis, decreases growth and viability, making it an ideal target for therapeutic intervention (Scaglia et al., 2009). However nothing is known about the mechanisms of SCD-1 action in progestin-sensitive breast cancers.

The mechanism of progesterone-mediated lipogenesis in breast cancer has not been explored in depth, especially in the context of metabolism and chemotherapeutic response. In these studies we investigated the role of the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) on lipid accumulation and chemotherapeutic response of two breast cancer cell lines that differ in their PR content. We found that progestins promote PR-mediated metabolic changes that favor chemotherapy survival in breast cancer cells by three mechanisms: 1) inducing de novo lipid synthesis using glucose from the growth medium, 2) modifying the phospholipid composition of membranes (greater unsaturated fatty acid content) and 3) sequestering docetaxel within enlarged lipid droplets. Since progestins are widely used in hormone replacement therapy and oral contraception (Ito et al., 2010), understanding their mechanisms of action at the cellular and metabolic levels are of critical importance and may provide novel targets for metabolic cancer therapies.

2. Methods

2.1 Cell culture and drug treatments

T47D and MDA-MB-231 (gifts from Kathryn Horwitz, University of Colorado) were authenticated by Single Tandem Repeat analysis (STR; University of Colorado Cancer Center) and were passaged in MEM (Invitrogen) containing 5% Fetal Bovine Serum supplemented with amino acids and Insulin (Hyclone). Drug treatments were done in phenol-red free 5% dextran-coated charcoal serum (DCC) to eliminate serum steroids. Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Sigma) was solubilized in ethanol and used at 10nM concentration for all experiments. ZK98,299 (Schering AG) was dissolved in ethanol and used at 100nM concentration. Docetaxel (LKT Labs) was solubilized in ethanol and used at 100nM concentration. SCD-1 inhibitor (#1716-1; 4-(2-Chlorophenoxy)-N-(3-(3-methylcarbamoyl)phenyl)piperidine-1-carboxamide) was purchased from BioVision (Mountain View, CA), dissolved in DMSO and used at 50nM. Glucose–depleted media was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2 Analyses for lipid content and proliferation

Breast Cancer cells (1×105 T47D; 5×104 MDA-MB-231) were plated on coverslips placed in 6-well plates and treated with ethanol or MPA (10nM). Cells were fixed with 4% Paraformaldehyde for 10 min followed by 4 min incubation with 50% ethanol at room temperature. Cover-slips were kept at 4°C in PBS until use. Oil red O staining was performed on the fixed coverslips according to the standard protocol (Koopman et al., 2001). Cells were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope mounted with a Nikon DS-Qi1Mc digital camera with Nikon Instruments Software (NIS) Elements software. Ten fields of each condition were used for the quantification of the Oil red O staining, using the NIH ImageJ software freely available on the web. Cell proliferation was performed using the Beckman Coulter Vi-Cell Automated Cell Viability Analyzer, which automates the widely accepted trypan blue cell exclusion method. For Vi-Cell analysis, cell densities were plated as above in 12-well dishes and treated with ethanol or MPA for 4 days in phenol-free 5% DCC serum-containing media. Cells treated with docetaxel were incubated for 2 additional days.

2.3 Immunoblots

For electrophoresis, 80μg of whole cell extracts were run on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose (Invitrogen). After blocking with 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), blots were incubated overnight with the primary antibody to PR (1:2000 mouse anti-PgR1294: Dako,); SCD-1 (1:500, Santa Cruz) or beta-actin (1:1000 rabbit, Cell Signaling). Blots were washed 3 times in PBST and followed by 1 hour incubation with corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen). Band signals were visualized with chemiluminescence ECL substrate (Pierce) and measured densitometrically using the AlphaEaseFC software (Alpha Innotech).

2.4 Glucose uptake

Basal and insulin-mediated glucose uptakes were determined as previously reported for human cells in vitro (Sarabia et al., 1992). Briefly, T47D cells (1×105) in 6-well plates were incubated in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate-HEPES (KRBH) buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 1% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), 2-deoxyglucose (0.5 mM; Sigma-Aldrich), and [1,2-3H]2-deoxy-Dglucose (1uCi/mL; GE Healthcare) for 20 min at 37°C. For insulin stimulation, a set of cells were incubated with 100 nM insulin for 20 minutes. The cells were washed with ice-cold KRBH buffer, harvested in 800ul of lysis buffer (Pierce Biotechnology), and then added to scintillation vials containing 5 ml of scintillation fluid. Radioactive counts were determined with a scintillation counter (LS6500; Beckman Coulter). Counts were converted to moles of glucose taken-up and normalized to the protein concentration of the lysates. To account for deoxyglucose uptake not mediated by transporters, counts were also measured in the presence of 20 μM cytochalasin B (Sigma-Aldrich) to obtain glucose transporter-mediated uptake.

2.3 Lipid analysis: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy

T47D cells were grown in 60mm plates and treated with ethanol or MPA for 6 days, with or without docetaxel for the last 48h. Cells were collected in 2 mls of PBS and an aliquot of 100μL was used for cell count using a hemocytometer for standardization. Lipids were extracted using the Bligh and Dyer method (BLIGH et al., 1959). Samples were shaken on a rotational mixer for 1.5 hours at 4°C, and then spun at 3,000 rpm for 15′ to separate phases. The organic bottom layer was dried down under N2 at 40°C, resuspended in chloroform, and added to aminopropyl solid phase extraction (SPE) columns (Supelclean LC-NH2, 3ml, Supelco Analytical). Phospholipids were isolated using SPE based on the methods originally described by Kaluzny (Kaluzny et al., 1985). The FFA fraction was methylated by adding 0.5 ml 2% sulfuric acid, capping, and heating at 100°C for 1.5 hours. Phospholipid fractions were converted to fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) by transmethylation using sodium methoxide. Concentration and composition analysis were performed on an HP 6890 gas chromatography system with a 30m DB-23 capillary column, connected to a HP 5973 mass spectrometer. Peak identities were determined by retention time and mass spectra compared to standards of known composition.

2.4 Lipid droplet isolation

T47D cells were grown in T-175 flasks and treated with MPA for 6 days with or without docetaxel as described above. Lipid droplets were isolated from a sucrose gradient as described (Taylor et al., 1997), with minor modifications: cell homogenates in 0.5M sucrose were cleared by a slow spin for 10min at 1300×g and the post-nuclear supernatants were loaded into SW40 ultra-clear tubes and centrifuged at 28,000rpm (100,000×g) for 1 hour. After centrifugation, the thin opaque lipid droplet layer was collected, transferred to a glass collection tube and kept at −80°C for lipid extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS/MS).

2.5 Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS/MS) for docetaxel

An aliquot of the lipid droplet preparation was mixed with 1 volume of ice-cold methanol, and paclitaxel (2ng, Sigma) was added to every sample as internal standard. Samples were diluted with water to a final methanol concentration under 15% and then applied onto SPE cartridges (Strata-X, 33 μm Polymeric Reversed Phase, 60 mg; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Cartridges were washed with 4 ml water and lipids were eluted with 1 ml methanol. The eluate was dried down and solubilized in a mixture of 40 μl HPLC solvent A (8.3 mM acetic acid, buffered to pH 5.7 with ammonium hydroxide) and 20 μl HPLC solvent B (acetonitrile/methanol, 65:35, v/v). An aliquot of each sample (25 μl) was injected into a C18 HPLC column (Ascentis 5 μm, 150 × 2 mm; Sigma) and eluted at a flow rate of 200 μl/min with a linear gradient from 45% to 98% HPLC solvent B, as follows: 45% B for 5 min, increased to 98% B in 14 min, held at 98% for 6 min, decreased to 45% B in 1 min, and re-equilibrated at 45% B for 4 min. The HPLC system was directly interfaced into the electrospray source of a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (API 3000; PE-Sciex, Thornhill, Ontario, Canada) for mass spectrometric analysis in the positive ion mode using multiple reaction monitoring of the specific mass-to-charge (m/z) transitions (parent-ion → product-ion) 808 → 527 (docetaxel) and 854 → 286 (paclitaxel), which have been previously used to identify docetaxel (Corona et al., 2011). Analysis was repeated with samples from three different experiments.

2.6 Statistics

All values are given as means plus standard deviations (SD). Differences in parameters between treatments were assessed by ANOVA tests followed by Tukey post-hoc analysis. A p value of ≤ 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 Progestin-induced lipid accumulation is associated with chemoresistance and mediated by PR

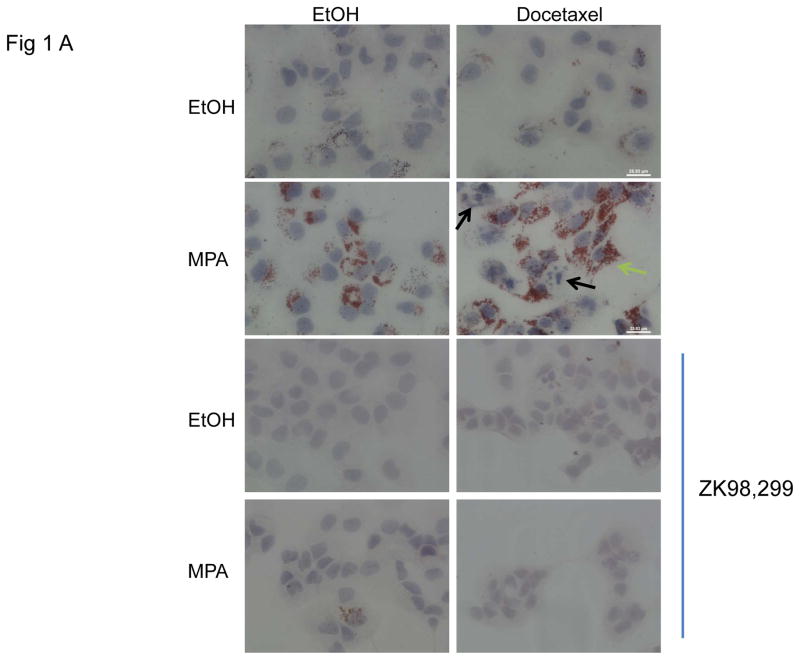

The luminal PR-positive breast cancer cell line T47D accumulates lipid when treated with progestin (Chalbos et al., 1987; Horwitz et al., 1985). Basal-like MDA-MB-231 PR-negative breast cancer cells were also used to examine the lipid biology of PR+ versus PR- breast cancer cells. We have examined the lipid content of the two cell lines, untreated or treated with the progestin MPA, using Oil red O (ORO) staining. Lipid staining was absent in MDA-MB-231 cells (not shown) but visible in the T47D cells (Fig. 1A). We also examined whether lipid droplet accumulation was affected by the chemotherapeutic agent, docetaxel. Docetaxel is a commonly used chemotherapeutic agent to treat advanced breast cancer (Lyseng-Williamson et al., 2005). Cells were treated with MPA or vehicle for 4 days to induce lipid accumulation followed by 2 days with or without docetaxel (with continuous MPA or vehicle treatment) and lipid content was assessed by ORO staining. A second set of cells grown in parallel was used to assay cell viability by trypan blue exclusion. Fig. 1A shows representative ORO photos of the T47D cells in the absence or presence of MPA, treated with or without docetaxel. MPA alone induces lipid accumulation as previously reported (2nd panel, left), and the combination of MPA+docetaxel also showed increased accumulation of lipid droplets (2nd panel, right). Interestingly, viable cells had lipid accumulation in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1A, 2nd panel, right, green arrow), while cells with apoptotic features (condensed DNA and/or fragmented nuclei) did not contain lipid droplets (black arrows).

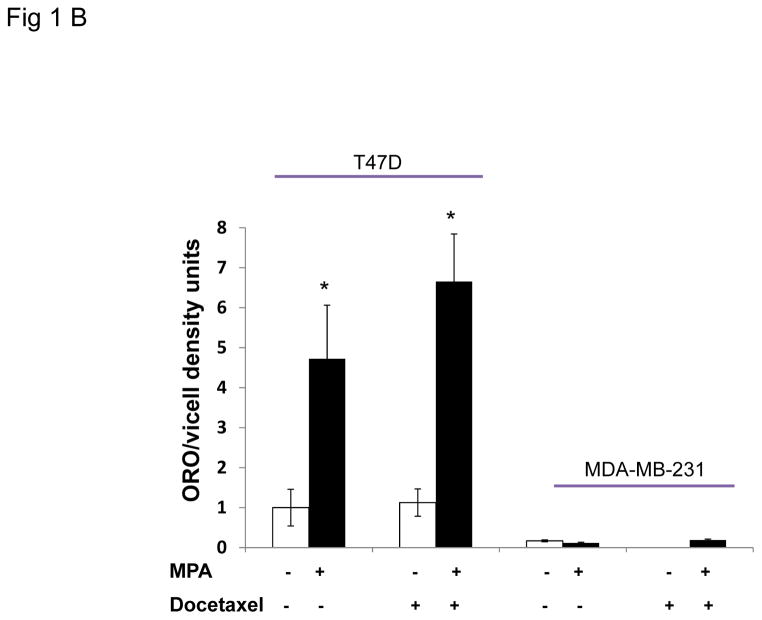

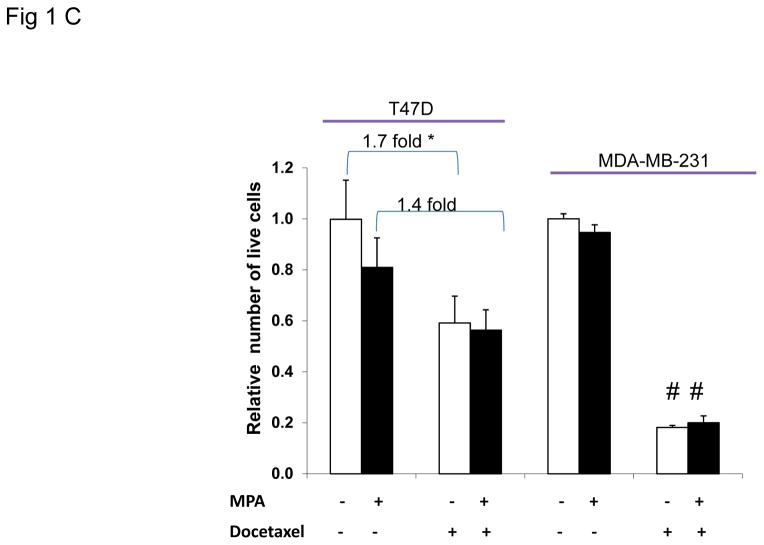

Figure 1. Progestin induces lipid accumulation and increases chemoresistance in PR+ breast cancer cells.

A, representative photographs of Oil red O stained T47D cells grown on coverslips and treated with or without MPA for 6 days. Docetaxel or ethanol (EtOH) was added for the last 2 days of treatment. Green arrow shows viable cell following docetaxel treatment, black arrows denote apoptotic cells. Lower panels: samples treated as above in the presence of the antiprogestin, ZK98,299. Lipid staining is absent in the presence of the anti-progestin. B, Quantification of Oil red O staining photographs of T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells using arbitrary density units. White and black bars represent ethanol and MPA treatments respectively. * p< 0.05, MPA versus vehicle for each cell line. Bars represent mean ±SD. Experiments were performed 5 times in independent triplicate assays. C, Number of viable T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells after MPA and docetaxel treatments as indicated above. Relative cell viability is shown for each cell line normalized to the untreated control.* p=0.02 vehicle vs. docetaxel for each treatment group (vehicle or MPA). # p< 0.001 vehicle versus docetaxel for each treatment group. Experiments were performed 7 times in independent triplicate assays.

To examine whether the lipid accumulation observed in the cells was PR dependent, the pure PR antagonist ZK98,299 (Classen et al., 1993) was used to block the effect of MPA on PR (Fig. 1A, 3rd and 4th panels). ZK98,299 was added for the entire incubation period with or without MPA and with or without docetaxel. ZK98,299 blocked the lipogenic effect mediated by MPA demonstrating that PR is necessary for progestin-mediated lipid accumulation in T47D cells. Quantification of lipid droplets shows MPA increased lipid formation ~4 fold over control in the PR+ T47D cells (p = 0.04) (Fig. 1B). The combination of docetaxel+MPA increased lipid accumulation 6.5 fold versus docetaxel alone (p= 0.001). We also examined two other PR+ breast cancer cell lines, BT-474 and ZR-75-1, and observed the same trend of MPA and MPA+docetaxel induced lipid accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 1A). We also examined PR levels in the three cell lines; T47D, BT-474 and ZR-75-1 and all express both isoforms of PR (PRA and PRB) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). The two PR isoforms can have differential effects on breast cancer biology (reviewed in (Scarpin et al., 2009)). To determine the contribution of each PR isoform to MPA induced lipid accumulation, lipid droplets were examined in T47D cell sublines that express no PR (T47D-Y cells), PRA only (T47D-YA cells), or PRB only (T47D-YB cells) (Sartorius et al., 1994). Lipid droplet accumulation was observed solely in breast cancer cells co-expressing PRA and PRB (Supplementary Fig. 2) but not in cells expressing only PRA, only PRB or no PR. Similarly, the PR-negative MDA-MB-231 cells do not accumulate lipid in response to MPA, docetaxel or the combination (Fig. 1B), underscoring the necessity of PR in mediating the response to MPA-induced lipid accumulation. Next we examined whether the increased lipid accumulation by MPA was associated with cell survival against docetaxel induced apoptosis, using trypan blue exclusion analysis. Fig. 1C shows the number of surviving cells with and without MPA and/or docetaxel treatment. MPA did not alter viability of MDA-MB-231 cells in the absence of docetaxel, however, docetaxel caused an 80% decrease in viable cells regardless of MPA treatment (p<0.01). This sensitivity is likely due to the high proliferation rate of MDA-MB-231 cells. After 6 days of MPA treatment, the number of T47D cells was slightly decreased versus untreated cells (1.25 fold) (p=0.1). Docetaxel decreased the number of T47D cells 1.7-fold in the absence of MPA (p=0.02). However, in the presence of MPA, docetaxel did not decrease the number of T47D cells significantly (1.4 fold, Fig. 1C), illustrating a more docetaxel resistant phenotype of progestin treated cells. In fact, microscopic examination of the MPA+docetaxel treated T47D cells showed lipid accumulation in the cytoplasm of viable cells but not in apoptotic cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, T47D cells that survived treatment with docetaxel+MPA contained more lipid than cells treated with MPA alone (Fig. 1B). Thus only viable T47D cells accumulate lipid droplets in response to docetaxel therapy and progestin decreases the sensitivity of PR+ cells to docetaxel induced apoptosis.

Progestins induce a biphasic change in the cell cycle of PR+ breast cancer cells, first inducing proliferation, then subsequent growth inhibition in G1/G0 for up to 96h (Musgrove et al., 1991). To determine whether T47D cells arrest in G1/G0 after 6 days of MPA-treatment therefore making them less sensitive to docetaxel, we performed flow-cytometry analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3A). MPA decreased the number of cells in G1/G0 and increased the percentage of cells in the S-phase of the cycle (8%, p=0.012). MPA also decreased the number of cells in G1/G0 upon docetaxel treatment with a concomitant increase in cells in G2M. We also examined cells for proliferation by BrdU incorporation. BrdU labeling increased in MPA-treated cells with or without docetaxel versus vehicle. Furthermore, BrdU accumulation was only observed in MPA treated cells containing lipid droplets with or without docetaxel, but in the absence of MPA none of the proliferating cells contained lipid droplets (Supplementary Fig. 3B and Fig. 3C). These data confirm MPA induces proliferation and show that lipid-loaded MPA-treated cells are not protected from docetaxel induced apoptosis by cell cycle arrest (Supplementary Fig. 3B and 3C). These data are consistent with previous reports that long term progestin treatment increases proliferation and antiapoptotic proteins in T47D cells (Moore et al., 2000).

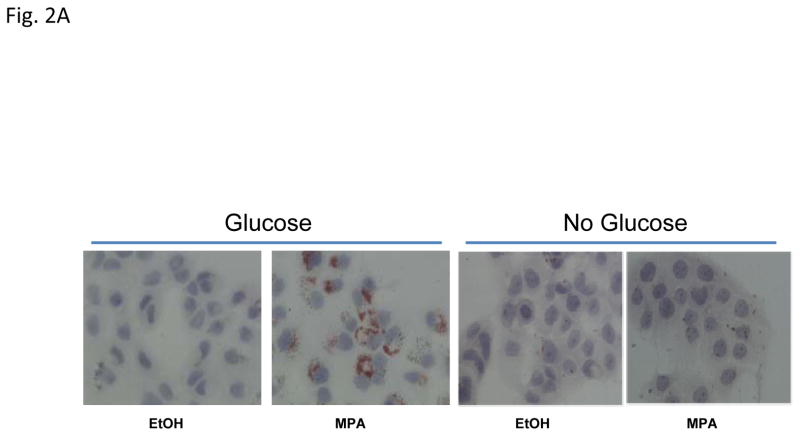

3.2 Lipid droplet formation requires glucose; progestin increases glucose uptake

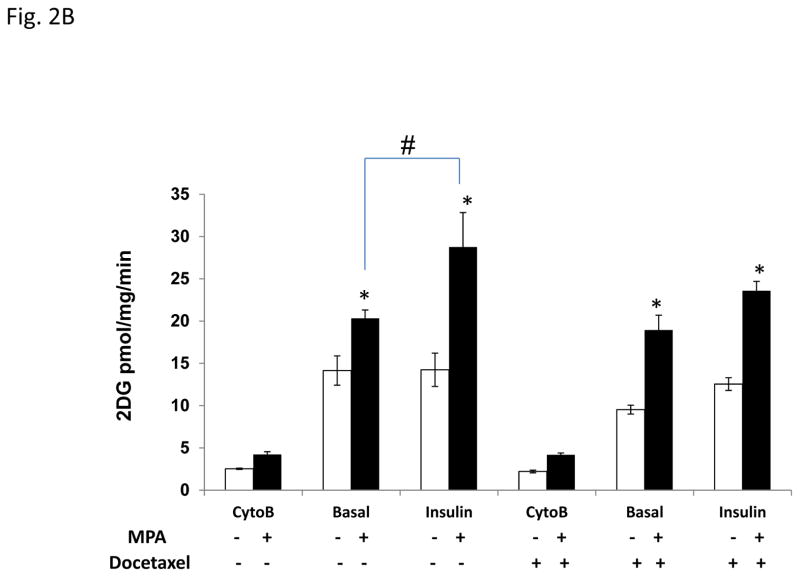

Glucose is a common precursor for de novo lipid formation. To investigate whether glucose in the culture media was required for MPA-induced lipid droplet formation, T47D cells were cultured in the presence or absence of glucose with or without MPA for 4 days (Fig. 2A). In contrast to the abundant lipid droplets induced by MPA in glucose containing media, glucose starved cells were unable to produce lipid droplets, illustrating that glucose uptake is absolutely required for lipid droplet formation in T47D cells (Fig. 2A). Because 1) lipogenesis increases in progestin treated T47D cells (Fig. 1), 2) glucose is required for MPA-induced lipid accumulation and 3) the media in which the cells are cultured is rich in glucose (25 mM), we speculated that MPA increased glucose uptake in T47D cells as a substrate for de novo lipid synthesis, which is mediated by the FASN enzyme from glucose (see Fig. 4A). Progestins increase the levels of insulin receptors in the plasma membrane and their effect could be associated with lipid accumulation (Horwitz et al., 1985), so we examined the effect of insulin-mediated glucose uptake in MPA-treated T47D cells. Fig. 2B shows the basal and insulin stimulated level of glucose uptake of T47D cells treated with or without MPA with or without docetaxel as measured by H3-2deoxy-labeled glucose. The microtubule inhibitor, Cytochalasin B (Cyto-B) was used to assess passive glucose uptake not mediated by transporters. Glucose uptake is low in cells treated with Cyto-B, however, MPA slightly stimulates glucose uptake 1.6-fold versus vehicle. Glucose uptake is 6 fold higher in the absence of Cyto-B (basal), and MPA stimulates glucose uptake 1.4-fold (p=0.054) compared to vehicle alone. Interestingly, insulin stimulation does not significantly increase glucose uptake above the basal levels in the absence of MPA, but MPA+insulin increases glucose uptake (1.8 fold, p<0.001), which may be mediated by insulin-sensitive transporters like GLUT4. Furthermore, when comparing basal MPA uptake to insulin+MPA glucose uptake, a significant increase was observed in the absence of docetaxel (1.4 fold, p< 0.01), suggesting a possible synergistic effect of MPA and insulin in T47D cells. Of note, progestin-induced glucose uptake is predominantly due to glucose transporters at the plasma membrane as previously reported (Medina et al., 2002).

Figure 2. Glucose uptake from the media is increased in progestin-treated cells and required for lipid droplet formation.

A, Photographs of Oil red O stains of T47D cells treated with vehicle or MPA with or without glucose. B, Glucose uptake of T47D cells treated with ethanol (white bars) or MPA (black bars) for 6 days. The last 2 days of treatment, cells were exposed to docetaxel where indicated. Cytochalasin-B (Cyto-B) was used to block glucose transporters and reveal the transporter-mediated glucose uptake. Bars represent mean ±SD. Statistically significant values between ethanol and MPA treatment are indicated: * p < 0.01, difference between ethanol (open bars) and MPA. # p=0.006, difference between MPA and MPA+insulin treatments. Experiments were performed three independent times in duplicate and one representative experiment is shown.

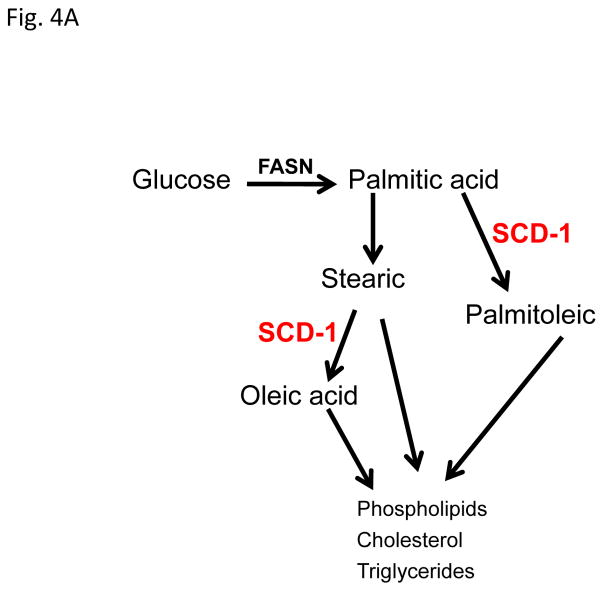

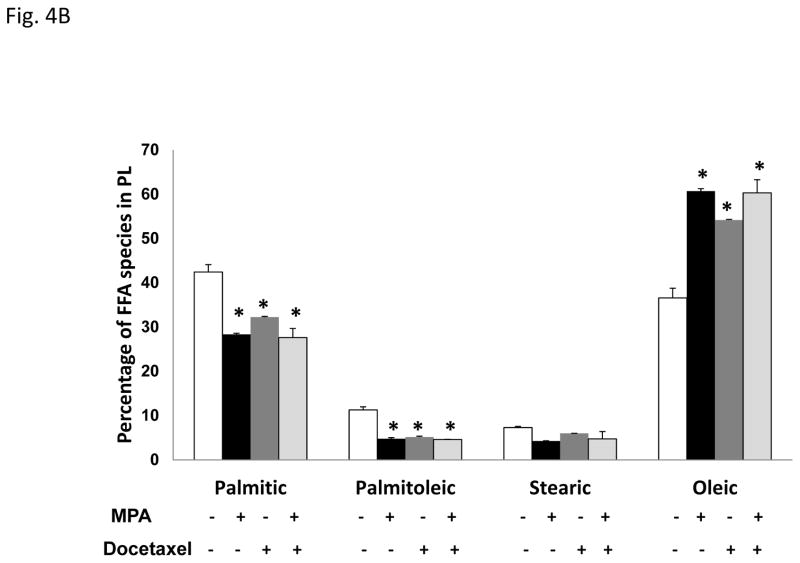

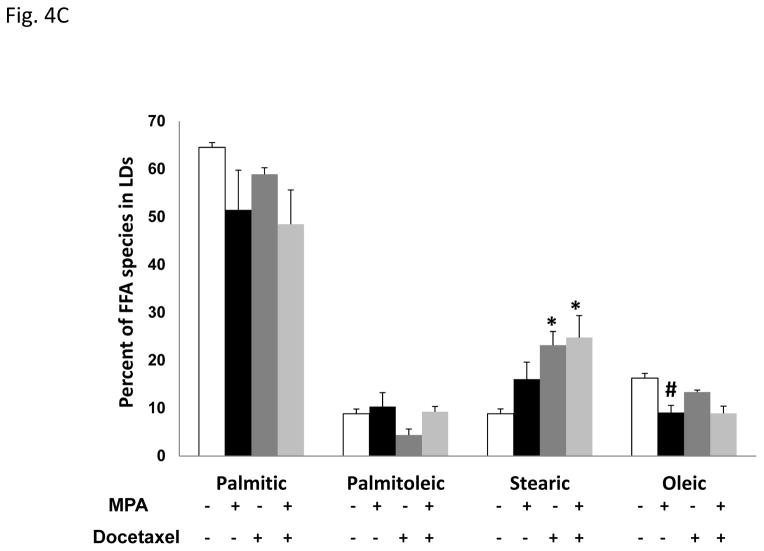

Figure 4. Progestin alters the lipid profile of T47D cells.

A, Diagram of the site of action of the SCD-1 enzyme. B, Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy (GCMS) analysis of most common fatty acids in the T47D phospholipid fraction: Palmitic (16C:0), palmitoleic (16C:1), stearic (18C:0) and oleic acid (18C:1). Bars represent mean ±SD. * p < 0.01, docetaxel, MPA or MPA+docetaxel treatment versus vehicle. C, GCMS of triglyceride fractions (lipid droplets) of T47D lipid extracts. Bars represent mean ±SD. * p ≤ 0.04, docetaxel or MPA+docetaxel treatment versus vehicle. # p = 0.01, vehicle versus MPA or MPA+docetaxel treatment.

Docetaxel treatment did not inhibit MPA induced glucose uptake. MPA treated cells showed a slight increase in passive glucose uptake (Cyto-B) and a significant 2.0 fold (p = 0.02) increase in basal glucose uptake. Insulin did not significantly further increase glucose uptake in the absence or presence of MPA. Thus, the majority of glucose uptake from the media is mediated by glucose transporters and glucose is the substrate used to generate the lipids observed in MPA-treated T47D cells, irrespective of docetaxel treatment.

3.3 SCD-1 expression is induced by progestin and it is required for lipid synthesis and cell growth

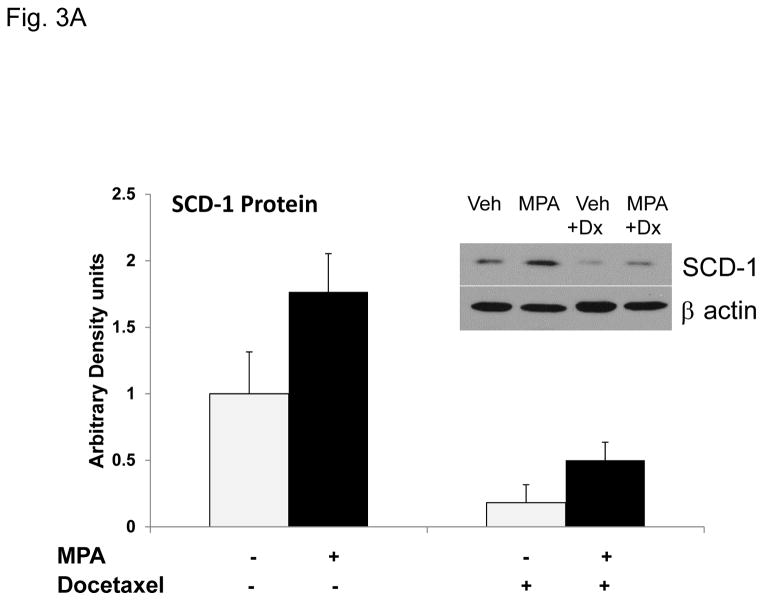

One mechanism of increased de novo fatty–acid synthesis is the increased expression/activity of lipogenic enzymes. Among them, fatty acid synthase (FASN) is expressed in many cancers and is also induced by progestins (reviewed in (Mashima et al., 2009)). Although FASN was more abundant in T47D than MDA-MB-231 cells, we did not observe induction of FASN upon 4 or 6 days of MPA (Supplementary Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B), implying that MPA induction of FASN occurs earlier than 4 days. Another enzyme, SCD-1, is essential for the processing/storage of lipids (Scaglia et al., 2009). SCD-1 converts fatty acids from saturated to unsaturated for use in phospholipid bilayer and/or storage in lipid droplets. Next we examined whether MPA affects SCD-1 expression. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that MPA strongly increased SCD-1 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 5). MPA induced SCD-1 protein ~2-fold in the absence or presence of docetaxel, although SCD-1 expression was significantly reduced by docetaxel (Fig. 3A), probably due to the toxic effects of docetaxel.

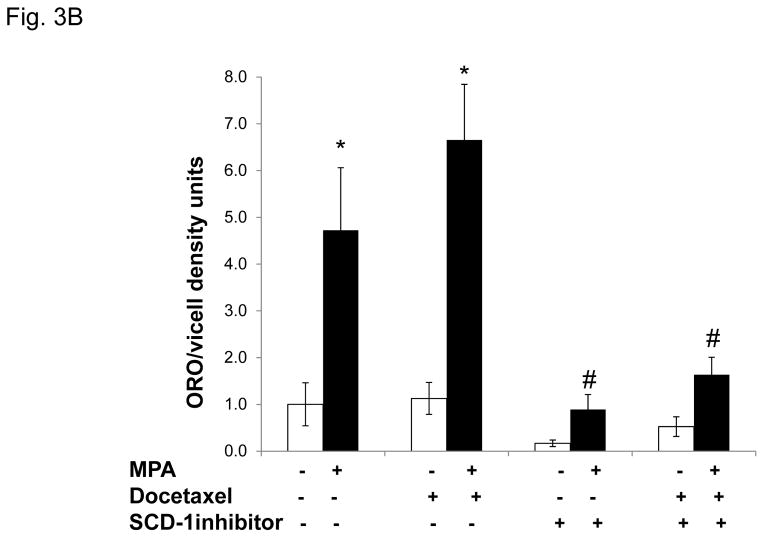

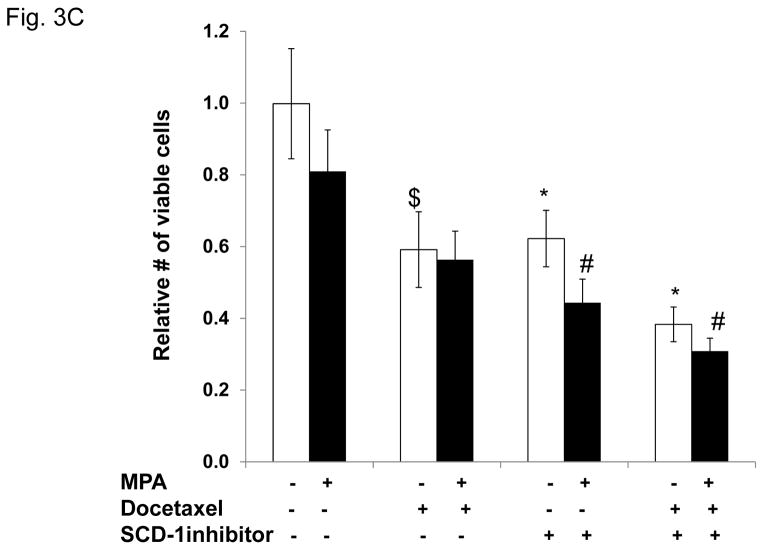

Figure 3. Progestin-mediated SCD-1 expression is required for lipid droplet formation and viability of T47D exposed to docetaxel.

A, Densitometry of two independent immunoblots for SCD-1 protein normalized to beta-actin is shown. Cells were treated as indicated. Inset; immunoblot for SCD-1 with β-actin as a loading control. B, Quantification of Oil red O staining of T47D cells after MPA and docetaxel treatments with or without SCD-1 inhibitor. White and black bars represent ethanol and MPA treatments respectively. * p< 0.05, MPA versus vehicle. # p ≤ 0.006 compared to MPA+docetaxel. Bars represent mean ±SEM of 5 independent assays in triplicate. C, Number of viable T47D cells after MPA and docetaxel treatments as indicated above. Relative cell viability is shown normalized to the untreated control. $ p=0.02 compared to vehicle alone. * p ≤ 0.005 compared to vehicle alone. # p ≤ 0.006 compared to MPA alone. Experiments were performed 7 times in independent triplicate assays.

In order to examine the effects of blocking SCD-1 on MPA-mediated lipogenesis and cell survival, we used a chemical inhibitor of SCD-1 activity (BioVision, #1716). Cells treated with MPA or vehicle with or without docetaxel were exposed to the SCD-1 inhibitor and stained for lipid droplets (Fig. 3B) and the number of surviving cells was quantified (Fig. 3C). MPA increased lipid droplet formation ~5 fold, (Fig. 3B). In the presence of MPA+docetaxel the lipid droplets increased 6.5 fold over docetaxel alone as we observed previously. Addition of the SCD-1 inhibitor in the absence of progestin dramatically reduced basal lipid droplet formation ~10 fold (Fig. 3B). While MPA treatment slightly increased lipid droplet formation, it was ~10-fold less than in cells treated with MPA or MPA+docetaxel only (Fig. 3B). The combination of the SCD-1 inhibitor+docetaxel reduced basal lipid formation by 50% and progestin slightly increased lipid droplet formation to approximately baseline levels, implying that progestins regulate other pathways involved in the formation of lipid droplets. Next we examined cell viability with MPA, docetaxel and the SCD-1 inhibitor (Fig. 3C). As observed before, progestin priming followed by docetaxel treatment caused a less dramatic decrease in cell number (1.4 fold) versus the vehicle treated group. Treatment with the SCD-1 inhibitor decreased the number of cells 1.6 fold (p=0.005). Addition of MPA to the SCD-1 inhibitor further decreased viability 1.4 fold versus the SCD-1 inhibitor alone and 1.8 fold versus MPA alone (p=0.006). The combination of docetaxel+SCD-1 inhibitor was more toxic; the number of cells decreased 2.6 fold versus no treatment (p<0.001) and cell numbers decreased 1.5 fold versus either docetaxel or the SCD-1 inhibitor alone. While addition of MPA to the combination of docetaxel and the SCD-1 inhibitor caused a further decrease in viability, it was not statistically significant. These results suggest that SCD-1 is required for the lipid phenotype mediated by MPA and its inhibition is toxic to cancer cells. The SCD-1 inhibitor also affects cell viability in the absence of MPA (with few lipid droplets) suggesting that other functions of SCD-1 are important for cancer cell viability.

3.4 Progestin and docetaxel alter the phospholipid and triglyceride profile of T47D cells

Since SCD-1 expression is increased by MPA and it plays a role in lipid droplet formation, we examined other functions of SCD-1 in progestin treated T47D cells. Fig. 4A shows a diagram of function of the SCD-1 enzyme in lipid metabolism from glucose carbons. SCD-1 catalyzes the synthesis of monounsaturated fatty acids (palmitoleic and oleic) from saturated fatty acids (palmitic and stearic acids). All of these fatty acids contribute to the generation of storage and structural complex lipids like phospholipids (membranes) and triglycerides (lipid droplets). Therefore, we examined the fatty acid content of T47D phospholipids and lipid droplets after MPA and/or docetaxel treatments, using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy (GCMS) analysis. Oleate (unsaturated) and palmitate (saturated) are the most common fatty acids circulating in blood, are abundant in cell membranes, and their levels are associated with breast cancer cell survival (Hardy et al., 2005; Przybytkowski et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the percentage of saturated lipids in the phospholipids (PL) and lipid droplets (LD) of T47D cells following MPA and/or docetaxel treatments. The majority of the saturated lipid (>74%) is found in the lipid droplets. However, we only observed significant changes among groups in the PL fraction (ANOVA, p=0.003). MPA decreased PL saturation 34% (p=0.004) when compared to vehicle treatment (p=0.004). Interestingly, docetaxel alone caused a similar decrease (23%) versus vehicle (p= 0.015). MPA was not significantly different from MPA+docetaxel treatments. Within lipid droplets (LD) saturation content was slightly increased (~ 9%) upon MPA and/or docetaxel treatment but differences among treatments were not significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Table of saturation content of the triglycerides (lipid droplets) and the phospholipids fractions of T47D cells treated with MPA for 6 days with or without docetaxel for the last 48 hours.

| Table of saturation content %(±SD)

| ||

|---|---|---|

| PL | LD | |

|

|

||

| vehicle | 50.59 (±1.64) | 74.88 (±0.16) |

| MPA | 33.14 (±0.31)*# | 80.59 (±4.44) |

| docetaxel | 38.79 (±0.05)* | 82.23 (±1.69) |

| MPA+docetaxel | 33.23 (±3.73)* | 80.06 (±2.11) |

Significantly different from vehicle (p<0.01)

Significantly different from docetaxel (p<0.02)

LD= Lipid Droplet; PL= Phospholipids

To determine the major species of fatty acids that compose the phospholipids, we examined all fatty acid species. The four most common fatty acids in the T47D cells treated with or without MPA, with or without docetaxel were palmitic (saturated), palmitoleic (unsaturated), stearic (saturated) and oleic acids (unsaturated) (Fig. 4B). Importantly, only surviving cells were analyzed. We did not detect any arachidonic acid in the samples, which reflects the absence of linoleic acid, the essential fatty acid precursor obtained from the diet which is not observed in cells grown in vitro.

Palmitic acid and oleic acid are the predominant fatty acids of T47D cell membranes (Fig. 4B), and they are also abundant in aggressive cancer cells (Nomura et al., 2010). MPA increased oleic acid content (1.7-fold, p=0.001) and concomitantly decreased palmitic acid (1.5-fold, p=0.002) within phospholipids. Similarly, docetaxel increased oleic acid (1.5-fold, p=0.002) with a concomitant decrease in palmitic acid (1.3-fold, p=0.005) in phospholipids and this effect was not enhanced by MPA. Importantly, the altered ratio of oleic:palmitic acid was significantly different in cells treated with MPA alone versus docetaxel alone. Other saturated fatty acids (palmitoleic and stearic) were minor components of the phospholipid fraction but also decreased with MPA, docetaxel and MPA+docetaxel. Palmitoleic acid may be toxic as it is associated with tumor cell death in rodents (Ito et al., 1982), which may explain why cells treated with MPA, docetaxel or both decrease the palmitoleic acid content at cell membranes (p< 0.001). Desaturation of stearic acid generates oleic acid, which is increased in MPA-treated and docetaxel-surviving cells, suggesting that the observed stearic acid decrease is due to desaturation to increase oleic acid. Interestingly, unbalanced levels of stearic (low) and oleic acid (high) levels are associated with breast cancer incidence in premenopausal women (Chajes et al., 1999). These data indicate that an altered ratio of fatty acids is a potential chemoresistance mechanism in breast cancer cells.

Figure 4C shows the predominant fatty acid within T47D lipid droplets was palmitic acid but we did not observe significant differences among treatment groups in the palmitic acid content of the lipid droplets (ANOVA, p= 0.13). However, MPA showed a trend to decrease Palmitic acid ~23%, and docetaxel modestly decreased it (10%). Treatment with MPA+docetaxel caused a similar decrease in palmitic acid as MPA alone. No significant changes in palmitoleic acid were observed. Stearic acid was significantly increased with docetaxel alone (2.6 fold, p= 0.038) and the combination of MPA+docetaxel (p= 0.03) did not further affect this increase. MPA strongly decreased oleic acid (1.8 fold, p=0.009) in lipid droplets and the combination of MPA+docetaxel caused the same decrease in oleic acid as MPA alone (p=0.009). These studies suggest a reciprocal lipid profile between membranes and lipid droplets.

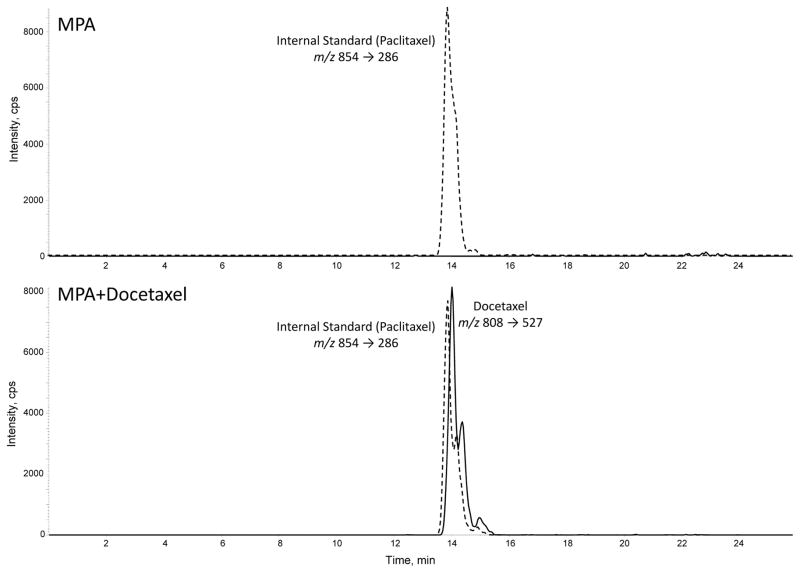

3.5 Intact docetaxel is sequestered in lipid droplets of progestin-treated cells

Because docetaxel is a lipid soluble drug that is found in lipoproteins within the plasma of cancer patients (Urien et al., 1996), we hypothesized that docetaxel could be sequestered in the MPA-induced lipid droplets of breast cancer cells. Thus, we isolated lipid droplets from T47D cells treated with MPA with or without docetaxel to examine them for intact docetaxel molecules. We used paclitaxel (analog of docetaxel) to serve as a reference peak for the analysis. The isolated lipid droplets were spiked with 2 ng of paclitaxel and then subjected to lipid extraction and LCMS/MS. Figure 5 shows the ion intensity peaks for paclitaxel and docetaxel. The upper panel shows analysis of lipids isolated from MPA-only treated cells; docetaxel is not detected. The lower panel shows the lipid analysis of MPA+docetaxel treated cells and shows a docetaxel peak that is slightly resolved chromatographically from the paclitaxel internal standard. This intensity peak corresponds to intact docetaxel molecules (m/z 808). Since docetaxel works by binding microtubules in the cytoplasm, we also analyzed the aqueous phase from the lipid extraction, but we did not detect any docetaxel peaks (data not shown), suggesting that docetaxel molecules are strongly associated with intracellular lipid droplets.

Figure 5. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy (LCMS/MS) analysis of docetaxel from isolated lipid droplets of T47D cells.

Paclitaxel was used as a reference molecule for the analysis. Total lipids from isolated lipid droplets of cells treated with MPA+vehicle (ethanol) or MPA+docetaxel (100nM) were extracted using solid-phase cartridges and analyzed by LC/MS/MS. The chromatograms show the ion intensity profiles for docetaxel (solid line) and paclitaxel (dashed line).

4. Discussion

The response of breast cancer cells to progestins is both proliferative and inhibitory, depending on the culture conditions (Groshong et al., 1997; Lin et al., 1999; Moore et al., 2006; Musgrove et al., 1991). However, cancer cells that adopt a lipid-loaded state may be able to survive most chemotherapeutic treatments. This lipid-based resistance could be one mechanism by which tumors recur after completion of chemotherapy regimens (Liu et al., 2008). Although other studies have investigated the role of lipid enzymes in the resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapy (Menendez et al., 2005), studies examining viability and lipid content at the cellular level are lacking.

In our breast cancer model, the amount of progestin-induced lipid formation correlates with 1) the presence of PR, 2) increased glucose uptake, 3) the activity of SCD-1 lipogenic enzyme and 4) protection from docetaxel induced apoptosis. Importantly, PR+ cells that survived docetaxel treatment contained lipid droplets and appeared healthy. In contrast the PR-negative MDA-MB-231 cell line lacked lipid droplets and were sensitive to docetaxel. While this implies lipid droplets play a role in chemoresistance, the underlying mechanism(s) are unknown.

We speculate that the lipophilic nature of taxanes (like docetaxel) provides PR+ breast cancer cells a way to sequester intact taxane molecules in the lipid droplets and away from microtubules, on which docetaxel exerts its anti-tumoral actions. Supporting this speculation is the fact that docetaxel circulating in the plasma binds to the surface of plasma lipoproteins (circulating lipid droplets) with high affinity (Urien et al., 1996). Additionally, our results show that lipid droplets of MPA-treated T47D cells contain intact docetaxel molecules, suggesting that cancer cells that accumulate lipid are able to sequester active taxane molecules and favor cancer cells survival. These results have important clinical implications since combinatorial therapies that target lipid synthesis and growth may be more effective for steroid responsive tumors which are known to accumulate lipid, like breast and prostate cancers.

The lipogenic protective effect we observe in T47D cells may not be exclusive for taxanes. Cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells are highly dependent on glucose uptake and lipid synthesis for survival, suggesting that a lipogenic phenotype is also a mechanism to escape cisplatin-induced cell death (Montopoli et al., 2011). If lipid loading in cancer cells is one mechanism promoting cancer cell survival, the positive effect of progestins on lipid accumulation in breast cancer cells may help explain increased cancer mortality in individuals who received hormone replacement therapy (Chlebowski et al., 2010).

Identification of the lipid species in progestin-stimulated lipogenesis is also important for elucidating putative mechanisms of cancer cell survival. In breast cancer cells the saturated fatty acid palmitate increases apoptosis, while the unsaturated fatty acid oleic acid increases proliferation and protects against palmitate-mediated apoptosis (Hardy et al., 2000). Fatty acids produced endogenously by cancer cells, as opposed to exogenous lipids, are also associated with a malignant and aggressive phenotype (Nomura et al., 2010). Analysis of phospholipids in T47D cells treated with MPA, docetaxel or both revealed a decrease in the saturation of fatty acids versus controls, a result most likely due to increased expression/activity of the SCD-1 desaturase enzyme by MPA. The mechanism(s) of MPA mediated regulation of SCD-1 expression is currently unknown. Taken together, the MPA induction of SCD-1 expression and the decreased survival of cells exposed to MPA+SCD-1 inhibitor strongly suggest the effects of MPA are mediated in part by SCD-1 activity. SCD-1 is not an early response gene as it is not up-regulated by 6 hours of MPA treatment in T47D cells (Ghatge et al., 2005) however, SCD-1 is clearly up-regulated by MPA after 6 days of treatment. This implies that progestin mediated regulation of SCD-1 is indirect however, the underlying mechanism is unknown.

Further analysis of cellular lipids confirmed that unsaturated oleic acid (product of SCD-1 activity) as the most abundant fatty acid in phospholipids. Because fatty acid composition was analyzed only in cells surviving docetaxel treatment, this suggests increasing the oleic acid content of the cancer membranes alters its composition and enhances cell survival, as others have also suggested (Baritaki et al., 2007). Docetaxel treatment also increases polyunsaturated fatty acids in MCF7 breast cancer cells (Bayet-Robert et al., 2009), suggesting membrane fluidity as a survival mechanism not unique to T47D cells. Examination of saturation content between phospholipids and lipid droplets also suggests reciprocal lipid content between membrane and storage lipid droplets. We speculate that shunting palmitate to the lipid droplets is a protective mechanism of lipogenic cancer cells, so excess palmitate does not accumulate in cell membranes. The possibility that an MPA induced increase in the saturation content of lipid droplets (more palmitate/less oleic) favors the sequestration of docetaxel in lipid droplets is an intriguing, untested idea.

Abundant glucose provides chemoresistance in T47D cells via FASN activity (Zeng et al., 2010). In cancer cells, progesterone increases glucose transporters (GLUT-1/3) and consequently glucose uptake, favoring cancer progression and increasing breast cancer risk (Medina et al., 2003). Our novel glucose uptake results in the presence of docetaxel suggest that the observed lipid accumulation of T47D cells in the presence of MPA+docetaxel is also driven by increased glucose uptake by MPA, underscoring the MPA-activated metabolic pathways for cancer cells survival. Furthermore, glucose is also used to generate, via glycolysis, the glycerol backbone for lipid droplet formation, which is consistent with increased glucose uptake preceding lipid droplet accumulation. Thus, glucose uptake stimulated by MPA fits with the role of progestins as enhancers of the well known glycolytic and lipogenic signature of breast cancer tumors (Szutowicz et al., 1979).

Conclusion

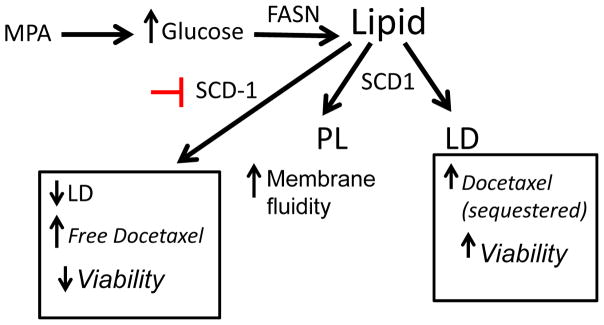

We propose the end results of progestin action are lipid bodies that sequester excess saturated lipid molecules as well as keeping docetaxel away from its site of action on microtubules (Fig. 6). Indeed, docetaxel plus inactivation of SCD-1 resulted in decreased viability of T47D cells as lipid droplets could not be formed to quench the active docetaxel. Our results suggest new combinatorial therapies using chemotherapy agents and natural, edible inhibitors of SCD-1 (like cyclopropene oils) that target lipid-loaded epithelial cancer cells would enhance chemosensitivity in luminal breast cancers.

Figure 6. Diagram of the proposed mechanism of progestin action in the lipid profile and survival of T47D cells exposed to docetaxel.

SCD-1 increases membrane fluidity and induces the formation of lipid droplets that are able to sequester active docetaxel molecules, favoring cell survival. SCD-1 inhibition leads to lack of lipid droplets, increased free docetaxel and decreased cell viability as well as increases membrane fluidity in the FASN, fatty acid synthase. SCD-1, steroyl CoA desaturase. PL, phospholipid. LD, lipid droplets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Avon Foundation (BMJ, IRS), Sanofi-Aventis Educational Grant (IRS), American Cancer Society Fellowship 117219-PF-09-287-01-CNE (IRS), Herbert Crane Endowment (IRS) and University of Colorado Cancer IRG# 57-001-50 (IRS). MAG is supported in part by a University of Colorado SPORE pilot grant (#63091285). We thank the Flow Cytometry and the DNA Sequencing & Analysis Cores of the University of Colorado Cancer Center. We also thank Dr. Kathryn Horwitz for the gift of the MDA-MB-231, ZR-75-1, T47D cells and sublines.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose

Reference List

- Badtke MM, Jambal P, Dye WW, Spillman MA, Post MD, Horwitz KB, Jacobsen BM. Unliganded progesterone receptors attenuate taxane-induced breast cancer cell death by modulating the spindle assembly checkpoint. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:75–87. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1399-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baritaki S, Apostolakis S, Kanellou P, Dimanche-Boitrel MT, Spandidos DA, Bonavida B. Reversal of tumor resistance to apoptotic stimuli by alteration of membrane fluidity: therapeutic implications. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;98:149–190. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)98005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayet-Robert M, Morvan D, Chollet P, Barthomeuf C. Pharmacometabolomics of docetaxel-treated human MCF7 breast cancer cells provides evidence of varying cellular responses at high and low doses. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLIGH EG, DYER WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chajes V, Hulten K, Van Kappel AL, Winkvist A, Kaaks R, Hallmans G, Lenner P, Riboli E. Fatty-acid composition in serum phospholipids and risk of breast cancer: an incident case-control study in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:585–590. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991126)83:5<585::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalbos D, Chambon M, Ailhaud G, Rochefort H. Fatty acid synthetase and its mRNA are induced by progestins in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9923–9926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalbos D, Joyeux C, Galtier F, Escot C, Chambon M, Maudelonde T, Rochefort H. Regulation of fatty acid synthetase by progesterone in normal and tumoral human mammary glands. Rev Esp Fisiol. 1990;46:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalbos D, Rochefort H. A 250-kilodalton cellular protein is induced by progestins in two human breast cancer cell lines MCF7 and T47D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;121:421–427. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)90199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalbos D, Vignon F, Keydar I, Rochefort H. Estrogens stimulate cell proliferation and induce secretory proteins in a human breast cancer cell line (T47D) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55:276–283. doi: 10.1210/jcem-55-2-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Gass M, Lane DS, Aragaki AK, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Ockene J, Sarto GE, Johnson KC, Wactawski-Wende J, Ravdin PM, Schenken R, Hendrix SL, Rajkovic A, Rohan TE, Yasmeen S, Prentice RL. Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2010;304:1684–1692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen S, Possinger K, Pelka-Fleischer R, Wilmanns W. Effect of onapristone and medroxyprogesterone acetate on the proliferation and hormone receptor concentration of human breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;45:315–319. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90348-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona G, Elia C, Casetta B, Frustaci S, Toffoli G. High-throughput plasma docetaxel quantification by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatge RP, Jacobsen BM, Schittone SA, Horwitz KB. The progestational and androgenic properties of medroxyprogesterone acetate: gene regulatory overlap with dihydrotestosterone in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R1036–R1050. doi: 10.1186/bcr1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groshong SD, Owen GI, Grimison B, Schauer IE, Todd MC, Langan TA, Sclafani RA, Lange CA, Horwitz KB. Biphasic regulation of breast cancer cell growth by progesterone: role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p21 and p27(Kip1) Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1593–1607. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.11.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S, Langelier Y, Prentki M. Oleate activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and promotes proliferation and reduces apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, whereas palmitate has opposite effects. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6353–6358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S, St Onge GG, Joly E, Langelier Y, Prentki M. Oleate promotes the proliferation of breast cancer cells via the G protein-coupled receptor GPR40. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13285–13291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IC, Berry DA, Demetri GD, Cirrincione CT, Goldstein LJ, Martino S, Ingle JN, Cooper MR, Hayes DF, Tkaczuk KH, Fleming G, Holland JF, Duggan DB, Carpenter JT, Frei E, Schilsky RL, III, Wood WC, Muss HB, Norton L. Improved outcomes from adding sequential Paclitaxel but not from escalating Doxorubicin dose in an adjuvant chemotherapy regimen for patients with node-positive primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:976–983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz KB, Sartorius CA. Progestins in hormone replacement therapies reactivate cancer stem cells in women with preexisting breast cancers: a hypothesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3295–3298. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz KB, Wei LL, Sedlacek SM, d’Arville CN. Progestin action and progesterone receptor structure in human breast cancer: a review. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1985;41:249–316. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571141-8.50010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Kasama K, Naruse S, Shimura K. Antitumor effect of palmitoleic acid on Ehrlich ascites tumor. Cancer Lett. 1982;17:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(82)90032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Utsunomiya H, Niikura H, Yaegashi N, Sasano H. Inhibition of estrogen actions in human gynecological malignancies: New aspects of endocrine therapy for endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge SM, Chatterton RT., Jr Progesterone-specific stimulation of triglyceride biosynthesis in a breast cancer cell line (T-47D) Cancer Res. 1983;43:4407–4412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoff RK. Metabolic effects of progesterone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:735–738. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzny MA, Duncan LA, Merritt MV, Epps DE. Rapid separation of lipid classes in high yield and purity using bonded phase columns. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen JC, Davidson NE. The biology of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:825–833. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman R, Schaart G, Hesselink MK. Optimisation of oil red O staining permits combination with immunofluorescence and automated quantification of lipids. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;116:63–68. doi: 10.1007/s004180100297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhajda FP. Fatty acid synthase and cancer: new application of an old pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5977–5980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakabe T, Maeda M, Hoshi N, Sugino T, Watanabe K, Fukuda T, Suzuki T. Fatty acid synthase is expressed mainly in adult hormone-sensitive cells or cells with high lipid metabolism and in proliferating fetal cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:613–622. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CA. Challenges to defining a role for progesterone in breast cancer. Steroids. 2008;73:914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin VC, Ng EH, Aw SE, Tan MG, Ng EH, Chan VS, Ho GH. Progestins inhibit the growth of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with progesterone receptor complementary DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Liu Y, Zhang JT. A new mechanism of drug resistance in breast cancer cells: fatty acid synthase overexpression-mediated palmitate overproduction. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:263–270. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons TR, Schedin PJ, Borges VF. Pregnancy and breast cancer: when they collide. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9119-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyseng-Williamson KA, Fenton C. Docetaxel: a review of its use in metastatic breast cancer. Drugs. 2005;65:2513–2531. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashima T, Seimiya H, Tsuruo T. De novo fatty-acid synthesis and related pathways as molecular targets for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1369–1372. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina RA, Meneses AM, Vera JC, Guzman C, Nualart F, Astuya A, Garcia MA, Kato S, Carvajal A, Pinto M, Owen GI. Estrogen and progesterone up-regulate glucose transporter expression in ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4527–4535. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina RA, Owen GI. Glucose transporters: expression, regulation and cancer. Biol Res. 2002;35:9–26. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602002000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:763–777. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez JA, Vellon L, Colomer R, Lupu R. Pharmacological and small interference RNA-mediated inhibition of breast cancer-associated fatty acid synthase (oncogenic antigen-519) synergistically enhances Taxol (paclitaxel)-induced cytotoxicity. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:19–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer WJ, Walker PA, III, Emory LE, Smith ER. Physical, metabolic, and hormonal effects on men of long-term therapy with medroxyprogesterone acetate. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montopoli M, Bellanda M, Lonardoni F, Ragazzi E, Dorigo P, Froldi G, Mammi S, Caparrotta L. “Metabolic reprogramming” in ovarian cancer cells resistant to Cisplatin. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:226–235. doi: 10.2174/156800911794328501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Conover JL, Franks KM. Progestin effects on long-term growth, death, and Bcl-xL in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:650–654. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Spence JB, Kiningham KK, Dillon JL. Progestin inhibition of cell death in human breast cancer cell lines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;98:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musgrove EA, Lee CS, Sutherland RL. Progestins both stimulate and inhibit breast cancer cell cycle progression while increasing expression of transforming growth factor alpha, epidermal growth factor receptor, c-fos, and c-myc genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5032–5043. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, Teutsch SM, Allan JD. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:872–881. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, Yeh J, Baehner FL, Fevr T, Clark L, Bayani N, Coppe JP, Tong F, Speed T, Spellman PT, DeVries S, Lapuk A, Wang NJ, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, Pinkel D, Albertson DG, Waldman FM, McCormick F, Dickson RB, Johnson MD, Lippman M, Ethier S, Gazdar A, Gray JW. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura DK, Long JZ, Niessen S, Hoover HS, Ng SW, Cravatt BF. Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates a fatty acid network that promotes cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2010;140:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory K, Lebeau J, Levalois C, Bishay K, Fouchet P, Allemand I, Therwath A, Chevillard S. Apoptosis inhibition mediated by medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment of breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;68:187–198. doi: 10.1023/a:1012288510743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Wanatabe M, Schoonjans K, Lydon J, O’Malley BW, Auwerx J. Progesterone receptor knockout mice have an improved glucose homeostasis secondary to beta -cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15644–15648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202612199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybytkowski E, Joly E, Nolan CJ, Hardy S, Francoeur AM, Langelier Y, Prentki M. Upregulation of cellular triacylglycerol - free fatty acid cycling by oleate is associated with long-term serum-free survival of human breast cancer cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85:301–310. doi: 10.1139/o07-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochon C, Prod’homme M, Laurichesse H, Tauveron I, Balage M, Gourdon F, Baud O, Jacomet C, Jouvency S, Bayle G, Champredon C, Thieblot P, Beytout J, Grizard J. Effect of medroxyprogesterone acetate on the efficiency of an oral protein-rich nutritional support in HIV-infected patients. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2003;43:203–214. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2003017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarabia V, Lam L, Burdett E, Leiter LA, Klip A. Glucose transport in human skeletal muscle cells in culture. Stimulation by insulin and metformin. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1386–1395. doi: 10.1172/JCI116005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius CA, Groshong SD, Miller LA, Powell RL, Tung L, Takimoto GS, Horwitz KB. New T47D breast cancer cell lines for the independent study of progesterone B- and A-receptors: only antiprogestin-occupied B-receptors are switched to transcriptional agonists by cAMP. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3868–3877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius CA, Harvell DM, Shen T, Horwitz KB. Progestins initiate a luminal to myoepithelial switch in estrogen-dependent human breast tumors without altering growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9779–9788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaglia N, Chisholm JW, Igal RA. Inhibition of stearoylCoA desaturase-1 inactivates acetyl-CoA carboxylase and impairs proliferation in cancer cells: role of AMPK. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpin KM, Graham JD, Mote PA, Clarke CL. Progesterone action in human tissues: regulation by progesterone receptor (PR) isoform expression, nuclear positioning and coregulator expression. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e009. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schedin PJ, Watson CJ. The complexity of the relationships between age at first birth and breast cancer incidence curves implicate pregnancy in cancer initiation as well as promotion of existing lesions. Preface. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:85–86. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Bremer E, Hasenclever D, Victor A, Gehrmann M, Steiner E, Schiffer IB, Gebhardt S, Lehr HA, Mahlke M, Hermes M, Mustea A, Tanner B, Koelbl H, Pilch H, Hengstler JG. Role of the progesterone receptor for paclitaxel resistance in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:241–247. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirling D, Ashby JP, Baird JD. Effect of progesterone on lipid metabolism in the intact rat. J Endocrinol. 1981;90:285–294. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0900285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Eystein LP, Borresen-Dale AL. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szutowicz A, Kwiatkowski J, Angielski S. Lipogenetic and glycolytic enzyme activities in carcinoma and nonmalignant diseases of the human breast. Br J Cancer. 1979;39:681–687. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1979.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RS, Jones SM, Dahl RH, Nordeen MH, Howell KE. Characterization of the Golgi complex cleared of proteins in transit and examination of calcium uptake activities. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1911–1931. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.10.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle S, Turkington VE. Effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate on carbohydrate metabolism. Obstet Gynecol. 1974;43:685–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urien S, Barre J, Morin C, Paccaly A, Montay G, Tillement JP. Docetaxel serum protein binding with high affinity to alpha 1-acid glycoprotein. Invest New Drugs. 1996;14:147–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00210785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARBURG O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager JD, Davidson NE. Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:270–282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Biernacka KM, Holly JM, Jarrett C, Morrison AA, Morgan A, Winters ZE, Foulstone EJ, Shield JP, Perks CM. Hyperglycaemia confers resistance to chemotherapy on breast cancer cells: the role of fatty acid synthase. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:539–551. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.