Abstract

This study examines the clinical correlates of alcohol craving in men and women self-referred for addiction treatment. Admission clinical data from patients participating in the Mayo Clinic 1-month Intensive Addictions Program were evaluated. Women had higher BDI and PACS scores compared with men in both the entire cohort and Dual Diagnoses group. Alcohol-dependent females had the most marked correlation between BDI and PACS (ρ =0.78). Further prospective study is encouraged to evaluate whether depressive symptoms and concomitant alcohol cravings in women are a marker for relief cravings and, as such, a target symptom for treatment intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Although the prevalence rates of an alcohol use disorder are more than twice as great for men than for women, the consequences of alcohol abuse and dependence are not only more severe but also more rapid in women.1 As a result, gender differences with regard to alcohol and its toxic effects have become increasingly researched. Multiple studies have shown that women develop higher blood alcohol concentrations than men after drinking equivalent amounts of alcohol per kilogram of body weight.2,3 Commensurate with these observations, the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism National Advisory Council defined binge drinking as “a pattern of drinking alcohol that brings blood alcohol concentration to 0.08 gram percent or above…this pattern corresponds to consuming five or more drinks for men, but only four or more drinks for women in about two hours.”4

Higher blood alcohol concentrations for equivalent doses of alcohol in women compared with men are not without consequences. Many studies have shown that women have heightened susceptibility to organ damage, such as alcohol related cardiomyopathy5 or liver disease,6 even when they have significantly fewer years of alcoholism than their male counterparts and consumed less cumulative lifetime alcohol. This faster progression to alcohol dependence has often been referred to as “telescoping.”7 In addition to cardiac and hepatic end organ damage, several representative studies have shown an increased sensitivity to alcohol-induced brain damage in women including global atrophy, hippocampal volume reduction, and reduced frontal gray matter N-acetylaspartate.8–10

Although women do present earlier, according to Dawson and colleagues, women are also less likely to ever have received treatment for their alcoholism.11 At the time of structured diagnostic interview confirming alcohol abuse or dependence, 23% of men vs 15% of women had received prior treatment (p<0.05). Furthermore, there appears to be an important gender difference in comorbidity patterns with women, compared with men, having higher rates of comorbid major depression (52% vs 32%) and increased severity of anxiety. Conversely, men, compared with women, have higher rates (49% vs 20%) of comorbid antisocial personality disorder.12–14

Craving is a complex set of cognitions and behaviors and has been recognized as a central component of alcohol dependence; it has been demonstrated to be associated with relapse even after prolonged periods of abstinence.15 Consequently, the identification of craving correlates and successful control of craving is a key element of treatment strategies in addiction treatment. Craving has been subdivided to reflect hypothesized neurobiological subtypes of reward craving (dopamine, opiate), relief craving (glutamate), and obsessive craving (serotonin).16 It has been hypothesized, but not confirmed clinically, that naltrexone may be more effective in individuals who experience reward craving and that acamprosate may be more effective in individuals who experience relief craving.17,18

Given the differences in time course to alcohol dependence (i.e. telescoping) and the differential comorbidity pattern, the study was conducted to explore whether women who sought addiction treatment for alcohol dependence, in comparison to men, had evidence of greater depression symptom severity and whether this correlated with cravings for alcohol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Mayo Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study (IRB #72-000218). Clinical data from patients who participated in the Mayo Clinic Intensive Addictions Program were evaluated. This physician-directed one-month program with on-site residence offers group-based psychotherapies and individualized pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence and dual diagnosis when clinically indicated. It is a physician-directed program with a multidisciplinary treatment team. Alcohol detoxification generally is completed, if needed, on a general hospital service before entry into the residential program. The number of subjects who required inpatient alcohol withdrawal plus the daily dose and duration of benzodiazepine treatment was not part of the clinical database and was not reliably identifiable.

Discharge clinical diagnosis [alcohol dependence (EtOH), additional Axis I diagnosis (DualDx)] was abstracted from the electronic medical record. Additional Axis I diagnoses included mood disorders (bipolar disorder, major depression, dysthymia), anxiety disorders (general anxiety, panic disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder), and drug abuse/dependence. Because of the small sample size of alcohol dependence + drug abuse/dependence, these subjects were incorporated into the DualDx group. Admission depressive symptoms were measured by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),19 and cravings for alcohol were measured by the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS).20 Additional clinical alcohol measures included age of onset of regular use of alcohol, maximum drinks consumed in a 24-hour period, and history of daily use and/or hazardous use preceding admission.

As presented in Table 1, the average age of the clinical cohort (n=281, 105F/176M) was 47.7±13.6 years (46.3±13 F/48.5±14 M). There were 72 subjects with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence only (22F/50M) and 209 subjects with a dual diagnosis of alcohol dependence and an additional Axis I diagnosis or drug abuse/dependence (83F/126M). Psychiatric diagnoses were similar for each gender with 44% of males and 50% of females meeting criteria for a comorbid mood disorder (p=0.274), 22% of males and 28% of females meeting criteria for a comorbid anxiety disorder (p=0.301), and 5% of males and 8% of females meeting criteria for an impulse or eating disorder (p=0.394). Forty-three (25%) of the patients with a non-substance psychiatric comorbidity had more than one.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics (mean ± SD) of alcoholics in treatment

| All (N=281) | Sex | Sex and diagnosis subtype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Female (N=105) | Male (N=176) | Female EtOH (N=22) | Female DualDx (N=83) | Male EtOH (N=50) | Male DualDx (N=126) | ||

| Age during treatment,* mean±SD | 47.7±13.6 | 46.3±13.0 | 48.5±13.9 | 54.3±10.7 | 44.1±12.8 | 52.3±12.4 | 47.0±14.2 |

| Age started regular use, mean±SD | 19.0±7.2 | 20.2±8.0 | 18.3±6.6 | 25.6±10.0 | 18.8±6.7 | 19.0±5.7 | 17.9±7.0 |

| Maximum drinks per day, mean±SD | 12.6±7.8 | 10.4±6.4 | 13.7±8.2 | 9.2±7.2 | 10.8±6.2 | 11.5±6.0 | 14.7±8.8 |

| Last use pattern, n (%) | |||||||

| Daily user | 133 (56%) | 42 (51%) | 91 (58%) | 11 (55%) | 31 (50%) | 31 (69%) | 60 (54%) |

| Non-daily | 105 (44%) | 40 (49%) | 65 (42%) | 9 (45%) | 31 (50%) | 14 (31%) | 51 (46%) |

| Hazardous user, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 192 (77%) | 68 (76%) | 124 (77%) | 15 (75%) | 53 (76%) | 37 (77%) | 87 (76%) |

| No | 60 (24%) | 22 (24%) | 38 (23%) | 5 (25%) | 17 (24%) | 11 (23%) | 27 (24%) |

Age started regular use is missing for 20, maximum drinks is missing for 83, last use pattern is missing for 43, and hazardous use is missing for 29 alcoholics.

All subjects who had admission BDI and PACS scores were included in this analysis. T-tests were used to test for demographic, depression, craving differences between diagnosis subtypes (EtOH alone vs DualDx), and differences between sexes. Spearman correlations (denoted by ρ) were used to examine potential relationships between BDI and PACS scores. Linear regression models with PACS score at admission as the dependent variable were used to investigate the impact of sex and diagnosis subtype on the relationship between depression and craving. In addition to models with main effects only, linear regression models were fit which included interactions among sex, diagnosis, and BDI score.

RESULTS

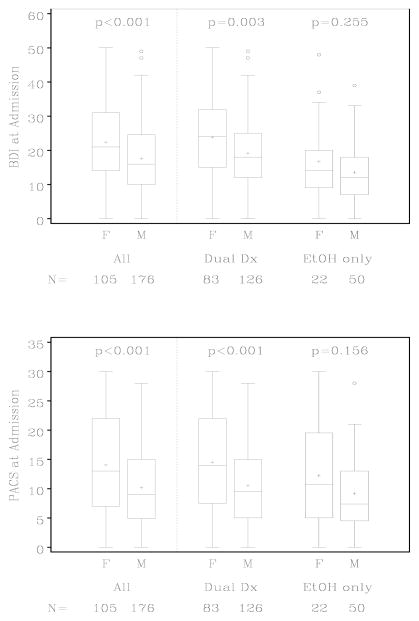

As presented in Figure 1, compared with men, women had significantly elevated depressive symptoms as measured by the BDI (mean for women 22.4±11.8, mean for men 17.6±10.2, t=3.47, two-sample t-test p<0.001). Patients with dual diagnoses also had elevated BDI scores (DualDx mean 21.0±11.0, EtOH only mean14.5±9.8, t=4.72 and p<0.001). When diagnosis subtype and sex were both considered in a linear regression model with BDI as the dependent variable, the BDI score was significantly associated with both effects (diagnosis p<0.001 and sex p<0.001). This model was repeated with the addition of the diagnosis subtype-by-sex interaction but the interaction term was not statistically significant (p=0.624).

FIGURE 1.

Admission depression and craving ratings

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory-II, PACS = Penn Alcohol Craving Scale

Women also reported elevated cravings for alcohol as measured by the PACS (mean for women 14.1±8.9, mean for men 10.2±7.1, t=3.83, and p<0.001). Those with comorbid psychiatric or drug disorders tended to have higher craving than those with alcohol dependence only, although this trend was not significant (DualDx mean 12.1±8.2, EtOH only mean 10.1±7.2, t=1.93, p=0.055). The significant relationship between sex and craving remained significant in a linear regression model with PACS as the dependent variable when adjusting for diagnosis (p<0.001), but the diagnosis did not provide additional information about the PACS (p=0.127). This model was repeated with the addition of the diagnosis subtype-by-sex interaction but the interaction term was not statistically significant (p=0.677).

BDI and PACS scores were significantly correlated (n=281, ρ=0.34, p<0.001) and the correlations did not differ in men and women (male n=176, ρ=0.27, female n=105, ρ=0.38) based on the sex-by-BDI interaction term in a linear regression model with PACS as the outcome (p=0.147). However, as presented in Table 2, when diagnosis was taken into account, gender differences were apparent. Regression models confirmed that the correlation between BDI and PACS in EtOH only women (ρ=0.78) was stronger than in DualDx women (ρ=0.27, comorbidity-by-BDI interaction p=0.026). On visual inspection, the lower correlation in DualDx women did not appear to be a ceiling effect (i.e., smaller range of scores caused by the fact that most patients in that group have a very high score). This was not true for men, for which the relationship between BDI and PACS was similar regardless of other psychiatric comorbidities (comorbidity-by-BDI interaction p=0.510).

TABLE 2.

Spearman correlations for admission BDI and PACS scores (n=281)

| Sex and comorbidity category | N (%) | Spearman correlation (ρ) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 281 | 0.34 |

| Female | 105 (37%) | 0.38 |

| Alcohol only | 22 (7.8%) | 0.78 |

| DualDx | 83 (29.5%) | 0.27 |

| Alcohol and psychiatric comorbidity | 48 (17%) | 0.36 |

| Alcohol and drug | 14 (4.9%) | 0.07 |

| Alcohol, drug, and psychiatric comorbidity | 21 (7.4%) | 0.14 |

| Male | 176 (62.6%) | 0.27 |

| Alcohol only | 50 (17.8%) | 0.16 |

| DualDx | 126 (44.8%) | 0.30 |

| Alcohol and psychiatric comorbidity | 63 (22.4%) | 0.23 |

| Alcohol and drug | 23 (8.1%) | 0.40 |

| Alcohol, drug, and psychiatric comorbidity | 40 (14.2%) | 0.39 |

Full model: sex X EtOH only X BDI p=0.007;

Females only: EtOH only X BDI p=0.046; Males only: EtOH only X BDI p=0.172;

Females with drug or psychiatric disorders: EtOH only X BDI p=0.328;

Males with drug or psychiatric disorders: EtOH only X BDI p=0.136.

DISCUSSION

This large retrospective clinical study suggests that women (compared with men) who present for elective admission for addiction treatment of alcohol dependence have increased depressive symptoms and cravings for alcohol. These elevations and gender differences appear to be most prominent in women with alcohol dependence and dual diagnoses of mood, anxiety, or additional drug abuse/dependence. These data would also suggest that the strongest positive correlation between depressive symptoms and cravings for alcohol were in women with alcohol dependence alone (ρ=0.78). The weaker correlation in women with dual diagnosis may represent BDI symptoms related to the additional primary mood disorder or a more heterogeneous group with a less specific relationship between depressive symptoms and craving. This would suggest the possibility that the depression inventory is identifying symptoms of depression that relate to craving in women with alcohol dependence.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and lack of a structured diagnostic interview. It is unlikely however, that major mood or anxiety disorders were missed in the alcohol alone groups, as the one-month physician directed program provided ample longitudinal assessment to clarify diagnoses. However, clinical assessments did not routinely delineate primary vs. secondary depression. Some of the subgroups (i.e., female alcohol dependence) are limited by small sample size. Furthermore, lack of controlling for admission medications in this clinical sample may have influenced depressive and/or craving scores. Whereas patients presented for admission often on antidepressants and/or mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines and antidipsotropics were rarely identified at admission. Another limitation to our baseline assessments is the impact of preceding alcohol withdrawal or detoxification and time of last drink. Any patient, by clinical assessment, that needs monitored detoxification with benzodiazepines (i.e. history of withdrawal symptoms, seizure) is admitted to a separate facility. This information plus benzodiazepine daily dose and duration of withdrawal treatment is not reliably available. These data, nonetheless, shed important light on gender differences in clinical presentation for addiction treatment that are not necessarily captured in clinical trials. They also contribute to the increasingly recognized morbidity of alcoholism in women.

As in larger epidemiological studies,21,22 fewer women were referred to addiction treatment in our cohort than men. Although this pattern may represent referral or physician bias,23 given the accelerated course of illness in women with such high degrees of comorbidity,24 it highlights that future studies specifically designed to address this treatment disparity are in order.

It is the concept of relief craving that may have important implications in this study given the relationship between depressive symptoms and cravings. Further prospective study is encouraged to evaluate whether depressive symptoms and concomitant alcohol cravings in women are a marker for relief cravings and, as such, a target symptom for treatment intervention. These studies can be easily incorporated into pharmacogenomic studies of antidipsotropic treatments.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Samuel C. Johnson Genomics of Addictions Program, Rochester, Minnesota.

The authors would like to thank and recognize the work of Maureen Drews M.S., Vicki Courson M.S., and Lori Solmonson for database management and manuscript preparation, respectively.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association Meeting, Washington, DC, May 5, 2008.

Declaration of Interests:

Ms. Boykoff, Ms. Stevens, and Drs. Schneekloth, Hall-Flavin, Loukianova, Karpyak, and Biernacka have nothing to disclose. AssureRx is a clinical decision support company that has licensed intellectual property that is owned by the Mayo Clinic; Dr. Mrazek has an interest in this intellectual property. Dr. Frye has received grant support from Pfizer, National Alliance for Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Mayo Foundation, is a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Dainippon Sumittomo Pharma, Medtronic, Ortho McNeil/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, Schering Plough, Sepracor, Pfizer, and has participated in CME supported activity from Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Schering-Plough. He is not on any speakers’ bureau nor does he have any financial interest/stock ownership/royalties.

References

- 1.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baraona E, Abittan CS, Dohmen K, et al. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Expe Res. 2001;25:502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frezza M, di Padova C, Pozzato G, Terpin M, Baraona E, Lieber CS. High blood alcohol levels in women. The role of decreased gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity and first-pass metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:95–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA Council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004 Winter. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urbano-Marquez A, Estruch R, Fernandez-Sola J, Nicolas JM, Pare JC, Rubin E. The greater risk of alcoholic cardiomyopathy and myopathy in women compared with men. JAMA. 1995;274:149–154. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530020067034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker U, Deis A, Sorensen TI, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology. 1996;23:1025–1029. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randall CL, Roberts JS, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Mattson ME. Telescoping of landmark events associated with drinking: a gender comparison. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:252–260. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann K, Batra A, Gunthner A, Schroth G. Do women develop alcoholic brain damage more readily than men? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:1052–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agartz I, Momenan R, Rawlings RR, Kerich MJ, Hommer DW. Hippocampal volume in patients with alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:356–363. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schweinsburg BC, Alhassoon OM, Taylor MJ, et al. Effects of alcoholism and gender on brain metabolism. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1180–1183. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson DA. Gender differences in the probability of alcohol treatment. J Subst Abuse. 1996;8:211–225. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelius JR, Jarrett PJ, Thase ME, et al. Gender effects on the clinical presentation of alcoholics at a psychiatric hospital. Comp Psychiatry. 1995;36:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hesselbrock MN, Meyer RE, Keener JJ. Psychopathology in hospitalized alcoholics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:1050–1055. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340028004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jellinek EM. The craving for alcohol. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1955;16:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verheul R, van den Brink W, Geerlings P. A three-pathway psychobiological model of craving for alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:197–222. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann K, Bruck R, Grann H, Zimmermann U, Heinz A, Smolka M. Searching for the acamprosate and naltrexone responders. International Society for Biomedical Research on Alcoholism Meeting; Mannheim, Germany. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rist F, Randall CL, Heather N, Mann K. New developments in alcoholism treatment research in Europe: Proceedings of symposia at the 2004 ISBRA meeting. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1127–1132. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory II. San Antonio, TX: Psychology Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1289–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, Pope HG, Jr, Hudson JI, Faedda GL, Swann AC. Clinical and research implications of the diagnosis of dysphoric or mixed mania or hypomania. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1633–1644. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.12.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Chou PS. Stress, Gender, and Alcohol Seeking Behavior. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse; 1995. Gender Differences in alcohol intake; pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawson NV, Dadheech G, Speroff T, Smith RL, Schubert DS. The effect of patient gender on the prevalence and recognition of alcoholism on a general medicine inpatient service. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:38–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02599100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frye MA, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, et al. Gender differences in prevalence, risk, and clinical correlates of alcoholism comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:883–889. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]