Abstract

Diazo esters, arylboranes and carbamoyl imines undergo a 3-component Mannich condensation reaction. Catalyzed by Cu(II) salts, the reaction affords the corresponding isocyanate Mannich product; one that can be easily trapped in situ by other nucleophiles. The Mannich condensation corresponds to an α,α-disubstituted enolate addition to imines. The reaction was rendered asymmetric using the (-)-phenylmenthol ester in good yield and selectivities.

Graphical abstract

Multicomponent condensation reactions are attractive synthetic strategies for the rapid construction of compounds.1 They are characteristically proficient due to operational efficiency, reagent accessibility, and value of the products generated.2 Boronates and boranes have proven most effective as carbon donors in these reactions most notably exemplified by the Petasis reaction.3 In 1968, John Hooz initially described the reaction of trialkylboranes with stabilized diazocompounds to afford α-alkylated nitriles and carbonyl compounds.4 In expanding the existing repertoire of multicomponent condensation reactions, we envisaged a 3-component Mannich condensation reaction that exploited this reactivity utilizing a carbon donor borane or boronate, an α-diazo ester, and an imine. Similar strategies are effective in a two-step process involving heteroatom-hydrogen insertion of diazocompounds and followed by carbonyl condensation reactions promoted by rhodium.5 In contrast, we proposed that in situ formation of an enolate equivalent using Hooz insertion chemistry6 would address the addition of α,α-disubstituted enolates to imines. Herein we report the successful development of a 3-component Mannich reaction employing this approach and the unanticipated result of using carbamoyl imines in the reaction, the isocyanate Mannich product.

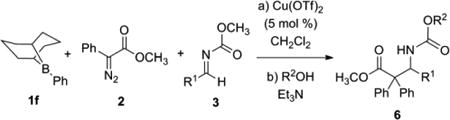

We initiated our investigations by evaluating boronate and borane carbon donors in the reaction utilizing α-diazo esters to make enolates competent in the Mannich condensation with acyl imines. Hooz demonstrated vinyloxyboranes were the intermediates generated from diazoacetate or diazoacetone and trialkylboranes, then vinyloxyboranes could be trapped by electrophiles, such as aldehydes, ketones or dimethyl(methylene)ammonium iodide.7 Similarly, Mukaiyama employed this approach for the in situ formation of boron enolates in the aldol reaction of benzaldehyde.8 The reaction of boronates and boroxines (1a – 1e) resulted in low conversion to the desired Mannich product although complete consumption of phenyl diazoester 2 and imine 3a occurred. The relatively low production of 4 was attributed to competing reaction pathways that result in decomposition of the imine or incomplete consumption of the diazoester (Table 1). The relative rate of boron enolate formation appeared to be slow using boronate carbon donors, with electron deficient boronate donors showing only marginal improvement in yield (Table 1, entries 2 and 4). However, the use of Ph-9-BBN 1f (B-phenyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane) gave the most appreciable yield of the Mannich adduct. We postulated that the use of a Cu catalyst may promote the decomposition of the diazoester and the subsequent Mannich reaction. Indeed, the use of 5 mole % Cu(NCCH3)4PF6 afforded the Mannich product 4 but also gave rise to an unanticipated product, isocyanate 5. A survey of the literature illustrates that chlorocatecholborane is capable of converting carbamates to the corresponding isocyanate under basic conditions.9 The same pathway appeared to be occurring under the Cu(I)-promoted reaction conditions. Further experimentation revealed Cu(OTf)2 to be the best catalyst, affording the isocyanate 5 in 76% isolated yield (Table 1, entry 9) with CH2Cl2 being the ideal solvent. The optimized reaction conditions utilized 5 mole % Cu(OTf)2, 1.1 equivalents of phenyl diazo ester, and 1.2 equivalents of imine relative to phenyl-9-BBN in CH2Cl2.

Table 1. Boron Enolate Mannich Reactionsa.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| entry | boron | catalyst | solvent | yield of 4 [%]b | yield of 5 [%]b |

| 1 | 1a | - | CH2Cl2 | 8 | - |

| 2 | 1b | - | CH2Cl2 | 10 | - |

| 3 | 1c | - | CH2Cl2 | <5 | - |

| 4 | 1d | - | CH2Cl2 | - | - |

| 5 | 1e | - | CH2Cl2 | 5 | - |

| 6 | 1f | - | CH2Cl2 | 22 | <5 |

| 7 | 1f | Cu(NCCH3)4PF6 | CH2Cl2 | 12 | 37 |

| 8 | 1f | CuOTf | CH2Cl2 | 13 | 55 |

| 9 | 1f | Cu(OTf)2 | CH2Cl2 | <5 | 76 |

| 10 | 1f | Cu(OTf)2 | PhCH3 | 13 | 44 |

| 11 | 1f | Cu(OTf)2 | THF | 6 | 20 |

Reactions were run with 1.0 mmol boronate 1, 1.0 mmol diazo ester 2, 1.0 mmol acyl imine 3a, in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M) for 12 h under Ar, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

In situ formation of the isocyanate afforded the opportunity to yield any carbamate from the Mannich reaction. Benzyl alcohol, allyl alcohol and 9-fluorenemethanol were effectively employed to generate the Cbz, Alloc or Fmoc protected amines 6a, b, and c, respectively, in good yields (Table 2, entries 1 – 3). The scope of the reaction proved to be general for both electron rich and electron deficient acyl imines utilizing benzyl alcohol to yield the corresponding Cbz carbamate (Table 2, entries 4 – 11). The cinnamaldehyde-derived imine afforded the 1, 2-addition product selectively in 71% isolated yield (Table 2, entry 4). Electron-deficient aromatic imines gave good yields, at room temperature (Table 2, entries 5 – 7). However, electron-rich aromatic imines underwent the condensation reaction in moderate to good yields, requiring 10 mole % Cu(II) to facilitate the reaction (Table 2, entries 8 – 10), as did the 2-naphthyl imine (entry 11).

Table 2. Four Component Boron Enolate Mannich Reactionsa.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| entry | R1 | R2 | product | yield [%]b |

| 1 | Ph | Bn | 6a | 75 |

| 2 | Ph | Allyl | 6b | 72 |

| 3c | Ph | Fm | 6c | 70 |

| 4 | (E)-PhCH=CH | Bn | 6d | 71 |

| 5d | 4-BrC6H4 | Bn | 6e | 71 |

| 6 | 3-FC6H4 | Bn | 6f | 75 |

| 7d | 3-BrC6H4 | Bn | 6g | 71 |

| 8e | 3-CH3OC6H4 | Bn | 6h | 80 |

| 9e | 3,4-(OCH2O)C6H3 | Bn | 6i | 62 |

| 10d | 4-CH3C6H4 | Bn | 6j | 79 |

| 11c,d | 2-naphthyl | Bn | 6k | 61 |

Reactions were run with 1.0 mmol B-Ph-9-BBN 1f, 1.1 mmol phenyl diazo ester 2, 1.2 mmol imine 3, 5 mol % Cu(OTf)2, in CH2Cl2 for 12 h under Ar, quenched with 5 equiv of alcohol and Et3N; mixed for an additional 5 h, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield of 6.

2 equiv benzyl alcohol and reflux for 1 h after Et3N treated.

5 mol % more Cu(OTf)2 added with imine and 10% DMF as the co-solvent.

5 mol % more Cu(OTf)2 added with imine.

The nature of the borabicyclononane carbon donor was also evaluated in the reaction. Both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing B-aryl-9-BBNs were suitably reactive and provided diastereoselectivies of 1:3 and 1:1.3, respectively (Table 3, entries 1 and 2). Both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing aryl diazoacetates provided similar yield, but lower diastereoselectivity (entries 3 and 4). Ethyl diazoacetate failed to provide the desired product under the current reaction conditions due to the undesired migration of the borabicylononane ring (Table 3, entry 5).10 However, the Mannich condensation reaction could be run with 2-alkyl-diazo esters. Ethyl 2-diazopropanoate 10, with Ph-9-BBN 1f and acyl imine 3a, provided the syn β-amino ester product 11 in 73% yield and 3:1 diastereoselectivity. The use of ethyl 2-diazopropanoate allowed us to isolate the corresponding silyl ketene acetal using N-trimethylsilylimidazole11 13 (Scheme 1). Upon isolation, a single enolate geometry was observed and determined to be the E-silyl ketene acetal. Despite the high selectivity in the formation of the enolate, the moderate selectivity in the ensuing Mannich reaction indicates multiple pathways in the imine addition reaction may be possible under Lewis acid-promoted conditions.12

Table 3. Diastereoselective Boron Enolate Mannich Reactionsa.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| entry | Ar | R1 | product | yield [%]b | dr |

| 1 | 4-CH3OC6H4 | Ph | 9a | 71 | 1:3 |

| 2 | 4-FC6H4 | Ph | 9b | 76 | 1:1.3 |

| 3c | Ph | 4-CH3OC6H4 | 9c | 75 | 1:1 |

| 4 | Ph | 4-FC6H4 | 9d | 81 | 1:1 |

| 5 | Ph | H | 9e | <5 | - |

Reactions were run with 1.0 mmol B-Ar-9-BBN 7, 1.1 mmol phenyl diazo ester 8, 1.2 mmol imine 3a, 5 mol % Cu(OTf)2, in CH2Cl2 for 12 h under Ar, quenched with 5 equiv of alcohol and Et3N and stirring for another 5 h, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

0.25 mol % Cu(OTf)2 was used in the reaction.

Scheme 1. Boron Enolate Mannich Reaction of Ethyl 2-Diazo-propanoate and Enolate Geomtery of Insertion.

We next sought to develop an asymmetric Mannich reaction using chiral phenyldiazoacetate esters (Table 4). The commercially available (-)-phenylmenthol proved to be the most effective chiral auxiliary among those investigated including (-)-trans-2-phenyl-1-cyclohexanol, (-)-menthol and (-)-borneol; affording the S-configuration at the new chiral center in 6:1 dr and 85% yield (Table 4, entries 1 – 5). Running this reaction less than -20 C° for 24 hours yielded the β-amino ester in 10:1 dr and 89% yield. The isocyanate precursor 16 can be isolated in crystalline form directly from the reaction in similar dr and yield (10:1 dr and 87% yield). The diastereomer purity could be further improved by recrystallization (up to 30:1 dr and 76% overall yield from the reaction). The absolute configuration was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis of 16 (Figure 1).

Table 4. Chiral Boron Enolate Mannich Reactionsa.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | product | yield [%]b | dr |

| 1 |

|

15a | 85 | 1:1 |

| 2 |

|

15b | 74 | 2:1 |

| 3 |

|

15c | 77 | 2:1 |

| 4 | (–)–menthyl | 15d | 79 | 1.2:1 |

| 5 | (–)–phenyl–menthyl | 15e | 85 | 6:1 |

| 6c | (–)–phenyl–menthyl | 15e | 89 | 10:1 |

Reactions were run with 1.0 mmol B-Ph-9-BBN 1f, 1.0 mmol phenyl diazo ester 14, 1.0 mmol imine 3a, 5 mol % Cu(OTf)2, in CH2Cl2 for 12 h under Ar, quenched with 5 equiv of methanol and Et3N and stirring for another 5 h, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

1.0 mmol 1f, 1.1 mmol 14, 1.2 mmol 3a were used, reaction was run for 24 h under -20 °C.

Figure 1. (S)-(–)-Phenylmenthyl 3-isocyanato-2,2,3-triphenyl propanoate 16.

We propose a mechanism for the borane insertion similar to one originally proposed by Hooz13 and Soderquist14 (Scheme 2). Enolate carbon attack of the diazo ester on the boron p-orbital followed by Ar-group migration with concomitant N2 displacement affords the boron enolate. The ensuing Mannich condensation with the imine yields the borated carbamate. Subsequent elimination of B-CH3O-9-BBN results in isocyante formation.

Scheme 2. Proposed mechanism for one-pot isocyanate formation.

In summary, we have developed a 3-component condensation reaction using diazo esters, arylboranes and carbamoyl imines. The reaction is catalyzed by Cu(II) salts and affords the corresponding isocyanate Mannich product; an intermediate that can be easily trapped in situ by other nucleophiles. The overall Mannich condensation is an α, α-disubstituted enolate addition to imines. The reaction was rendered asymmetric using the (-)-phenylmenthol ester in good yield and selectivities. Ongoing studies include expansion of the scope and utility of the reaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH (R01 GM078240)

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Synthetic procedures, CIF file of compound 16, together with characterization and spectral data for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Petasis NA. In: Multicomponent Reactions. Zhu J, Bienaymé H, editors. WILEY-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tietze LF. Chem Rev. 1996;96:115. doi: 10.1021/cr950027e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Armstrong RM, Combs AP, Tempest PA, Brown SD, Keating TA. Acc Chem Res. 1996;29:123. [Google Scholar]; (d) Murakami M, Ugi I. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:3168. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3168::aid-anie3168>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tietze LF, Brasche G, Gericke KM. Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis. WILEY-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Petasis NA, Akritopoulou I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:583. [Google Scholar]; (b) Petasis NA, Zavialov IA. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:445. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Hooz J, Linke S. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:5936. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hooz J, Linke S. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:6891. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hooz J, Gunn DM. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:6195. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Zhu Y, Chen Z, Mi A, Hu W, Doyle MP. Org Lett. 2003;5:3923. doi: 10.1021/ol035490p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hu W, Xu X, Zhou J, Liu W, Huang H, Hu J, Yang L, Gong L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7782. doi: 10.1021/ja801755z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For selected reactions using the Hooz insertion chemistry, see; (a) Barluenga J, Tomás-Gamasa M, Aznar F, Valdés C. Nature Chem. 2009;1:494. doi: 10.1038/nchem.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Peng C, Zhang W, Yan G, Wang J. Org Lett. 2009;11:1667. doi: 10.1021/ol900362d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Hooz J, Bridson JN. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:602. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hooz J, Oudenes J, Roberts JL, Benderly A. J Org Chem. 1987;52:1347. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukaiyama T, Inomata K, Muraki M. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:967. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Valli VLK, Alper H. J Org Chem. 1995;60:257. [Google Scholar]; (b) Butler DCD, Alper H. Chem Commun. 1998:2575. [Google Scholar]

- 10.For examples of undesired migration of B-phenyl-9-BBN ring. see:; (a) Hooz J, Gunn DM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969;40:3455. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fang GY, Wallner OA, Di Blasio N, Ginesta X, Harvey JN, Aggarwal VK. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14632. doi: 10.1021/ja074110i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooz J, Oudenes J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:5695. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Suginome M, Uehlin L, Yamamoto A, Murakami M. Org Lett. 2004;6:1167. doi: 10.1021/ol0497436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hagiwara H, Iijima D, Awen BZS, Hoshi T, Suzukic T. Synlett. 2008;10:1520. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooz J, Oudenes J, Roberts JL, Benderly A. J Org Chem. 1987;52:1347. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canales E, Prasad KG, Soderquist JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11572. doi: 10.1021/ja053865r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.