Abstract

Asymmetric placement of the photosensory eyespot organelle in Chlamydomonas is patterned by mother-daughter differences between the two basal bodies, which template the anterior flagella. Each basal body is associated with two bundled microtubule rootlets, one with two microtubules and one with four, forming a cruciate pattern. In wild type cells, the single eyespot is positioned at the equator in close proximity to the plus end of the daughter rootlet comprising four microtubules, the D4. Here we identify mutations in two linked loci, MLT1 and MLT2, which cause multiple eyespots. Antiserum raised against MLT1 localized the protein along the D4 rootlet microtubules, from the basal bodies to the eyespot. MLT1 associates immediately with the new D4 as it extends during cell division, before microtubule acetylation. MLT1 is a low-complexity protein of over 300,000 daltons. The expression or stability of MLT1 is dependent on MLT2, predicted to encode a second large, low-complexity protein. MLT1 was not restricted to the D4 rootlet in cells with the vfl2-220 mutation in the gene encoding the basal body-associated protein centrin. The cumulative data highlight the role of mother-daughter basal body differences in establishing asymmetry in associated rootlets, and suggest that eyespot components are directed to the correct location by MLT1 on the D4 microtubules.

Introduction

Microtubules and microtubule-based structures play critical roles in determining cell structure and organization in eukaryotic cells as diverse as vertebrate neurons or epithelial cells, single-celled protists, and the cells of land plants [Vladar et al., 2012; Sakakibara et al., 2013; Hamada, 2014; Hayes et al., 2014]. Microtubule assembly and organization is dependent on microtubule organizing centers such as basal bodies or centrioles, and on a wide variety of microtubule associated proteins (MAPs) that stabilize, destabilize, modify, bundle, sever, and/or move along microtubules [Glotzer, 2009; Struk and Dhonukshe, 2014]. In the unicellular, photosynthetic alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, placement of the single, photosensory eyespot is dictated by the location of specific basal body-associated microtubules, providing an excellent model system in which to study the relationship between basal bodies, microtubules, and cell organization [Holmes and Dutcher, 1989; Dutcher, 2003; Mittelmeier et al., 2011; Marshall, 2012].

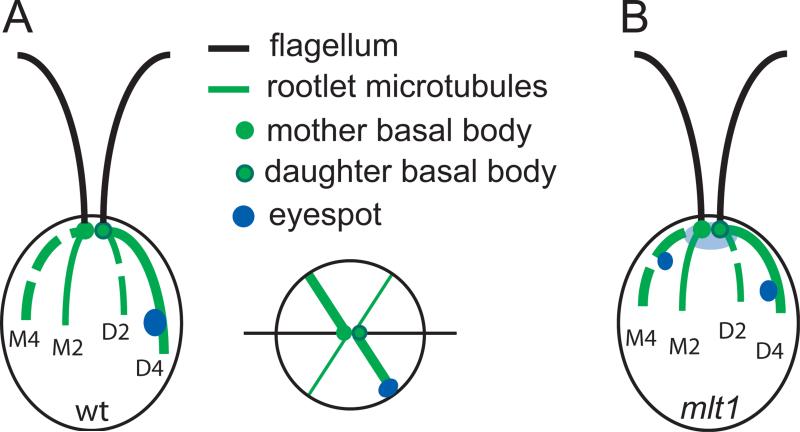

In Chlamydomonas, two mature basal bodies, the Mother and Daughter, are at the anterior end of the cell where they template flagellar assembly (Figure 1A). Each basal body is associated with two cytoplasmic microtubule “rootlets” that lie close to the plasma membrane and extend from the basal body toward the posterior of the cell [Ringo, 1967; Cavalier-Smith, 1974; O'Toole et al., 2003; Geimer and Melkonian, 2004]. One rootlet of each pair comprises two microtubules (M2 and D2) and the other comprises four microtubules in a three-over-one pattern (M4 and D4) [Goodenough and Weiss, 1978]. Like flagellar microtubules, the rootlet microtubules are highly acetylated [LeDizet and Piperno, 1986]. The daughter basal body matured just prior to the most recent cell division, assembly of the associated D4 and D2 rootlets began during metaphase, and the rootlet microtubules were acetylated shortly thereafter [Gould, 1975; Gaffal, 1988; Mittelmeier et al., 2013; O'Toole and Dutcher, 2014]. The mother basal body and rootlets were assembled and acetylated during a previous division. The eyespot, which comprises a patch of rhodopsin-family photoreceptors in the plasma membrane and underlying layers of pigment granules and chloroplast membranes, is invariably assembled adjacent to the nascent D4 rootlet in newly divided cells [Holmes and Dutcher, 1989; Kreimer, 2009; Engel et al., 2015]. This precise placement of the eyespot at an asymmetric position relative to the flagella is crucial for phototaxis [Witman, 1993]. Eyespot proteins such as the channelrhodopsin photoreceptors, ChR1 and ChR2 [Schmidt et al., 2006; Berthold et al., 2008; Sineshchekov et al., 2009], first begin to accumulate at the distal (plus end) tips of the newly polymerized D4 microtubules during cell division, and ChR1 has been observed along the outer surface of the D4 rootlet in interphase cells [Mittelmeier et al., 2011, 2013]. These data prompted the hypothesis that D4 microtubules direct trafficking of the photoreceptors from the anterior end of the cell to the position of the eyespot, but the identity of putative trafficking components and the basis for their specificity for D4 microtubules remains unknown.

Figure 1. The Chlamydomonas flagellar apparatus and eyespot.

(A) Illustration of a wild-type Chlamydomonas cell viewed from the side (left) or from the anterior/flagellar pole (right). Flagella extend from two mature basal bodies, each of which is associated with two acetylated microtubule rootlets, one comprising four microtubules (thick green lines) and one comprising two microtubules (thin green lines). Maturation of the Daughter basal body and assembly of the associated rootlets occurred during the most recent cell division while assembly of the Mother basal body and rootlets occurred during a previous division. The eyespot is always associated with the daughter four-membered microtubule rootlet (D4). (B) Illustration of a mlt1 mutant cell. The basic organization of mlt1 cells is the same as that of wild-type cells, but the following phenotypic differences have been described: (1) mlt1 cells are unable to phototax, (2) most cells contain ≥ 2 eyespots that are associated with D4 or with another rootlet, most often M4, (3) the acetylated D4 rootlet is shorter than that in wild-type cells, and (4) immediately following cell division, the major eyespot photoreceptors, ChR1 and ChR2, accumulate at the anterior end of the cell (light blue shading) rather than at the newly-assembling eyespot(s). Eventually the photoreceptors localize at the eyespots.

In contrast to single-eyed wild-type cells, mlt1 mutant cells are unable to phototax, and have one primary D4-associated eyespot plus one or more additional eyespots associated with either the D4 or with another rootlet, most often the M4 (Figure 1B) [Pazour et al., 1995; Lamb et al., 1999; Mittelmeier et al., 2011; Boyd et al., 2011a]. The eyespots in mlt1 cells typically occupy more anterior positions than that of the equatorial wild-type eyespot. In dividing mlt1 cells, ChR1 and ChR2 accumulate at the anterior end of the cell and localization to the primary eyespot is delayed, suggestive that the MLT1 protein promotes photoreceptor movement along the D4 rootlet [Mittelmeier et al., 2013]. Here we identify MLT1 as a large, low-complexity protein that is specifically associated with D4 microtubules from their minus ends near the basal bodies to the position of the eyespot. In dividing cells, MLT1 was associated with the nascent D4 rootlet prior to microtubule acetylation. Expression or stability of MLT1 was dependent on MLT2, predicted to encode a second large, low-complexity protein, while restriction of MLT1 to the D4 rootlet was dependent on wild-type basal body organization. Together, the data suggest a model in which a MLT1-MLT2 complex links the inherent asymmetry of the microtubule-based flagellar/basal body apparatus to the asymmetric localization of eyespot components.

Results and Discussion

MLT1 associates specifically with the D4 rootlet

The MLT1 gene (Cre12.g509850) was identified by a combination of phenotypic rescue, genetic mapping, and whole genome sequencing (details are provided in Materials and Methods and Tables S1 and S2 in supplementary material). The predicted 306.6 kDa MLT1 protein (Figure 2A) is of low complexity (> 50% of residues are Ala, Gly, Ser, or Pro) and has no identifiable functional domains; searches of GenBank using the BLAST algorithm yielded only short stretches of similarity to a predicted 2873 residue Volvox carteri protein (GenBank accession EFJ50705). MLT1 sequences can be accessed using the Cre*.* identifier as a keyword to search the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii genome v5.5 at the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) Phytozome 10 portal (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html).

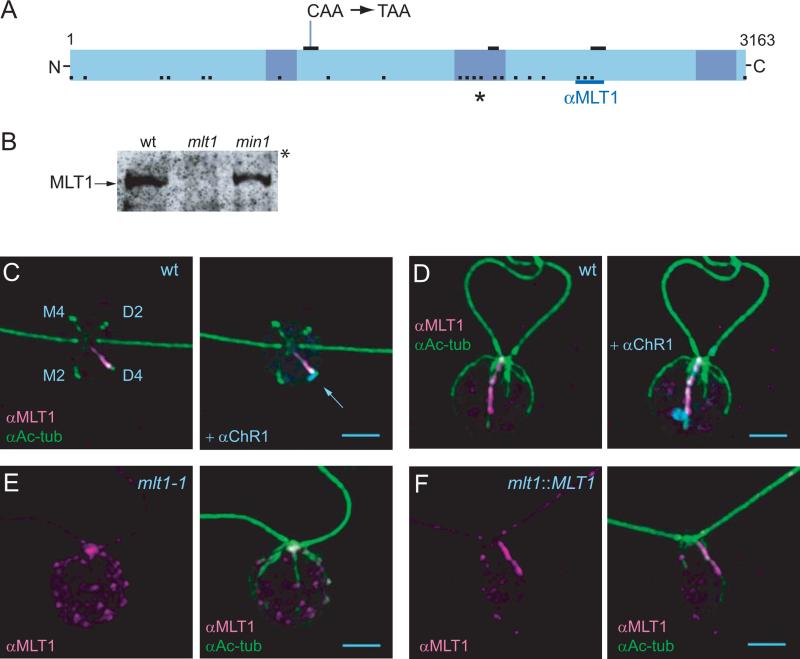

Figure 2. MLT1 associates with the D4 rootlet.

(A) Cartoon of the linear organization of the MLT1 protein including: the mlt1-1 nonsense mutation at residue 1131, three short stretches of homology to a predicted Volvox carteri protein (JGI ID 8849, heavy black bars), three basic regions (shaded boxes), the largest of which was targeted for mutagenesis (asterisk), twenty-two phosphorylation sites identified with 95% phosphosite localization confidence (black dots) [Wang et al., 2014a], and the sequence used for production of anti-MLT1, residues 2648 through 2759 (dark blue line). (B) Western blot of whole cell protein from equal numbers of wild-type (wt), mlt1-1 mutant, or min1 mutant (mini-eye, phototaxis negative control) cells separated by 5% SDS-PAGE and probed with affinity-purified anti-MLT1 polyclonal antibody. The asterisk indicates the top of the gel. The entire length of the blot is shown in Figure S1 in supplementary material. (C and D) Immunoflourescence microscopic (IF) images of wild-type cells labeled with anti-MLT1 and anti-Ac-tub alone (C), or in conjunction with anti-ChR1 (D). (E) IF image of a mlt1 mutant cell labeled with anti-MLT1 and anti-Ac-tub. (F) IF image of a mlt1 mutant cell that was phenotypically rescued by transformation with wild-type MLT1 genomic sequence (Materials and Methods, and Table S2 in supplementary material) labeled with anti-MLT1 and anti-Ac-tub. Scale bars = 2 μm.

As a first step toward understanding how MLT1 promotes photoreceptor localization along D4 microtubules, we raised a MLT1-specific polyclonal antiserum, which detected a >300 kDa protein in wild-type cell lysates (Figure 2B, Figure S1 in supplementary material). The protein was not detected in lysates of the mlt1-1 mutant strain or from two out-crossed mlt1-1 progeny. By indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (IF), anti-MLT1 labeling was observed along the single acetylated rootlet associated with the ChR1 photoreceptor patch in wild-type cells (Figures 2C and 2D) and in mlt1-1 cells that were phenotypically rescued following transformation with the wild-type MLT1 genomic sequence (Figure 2F, Table S2 in supplementary material). Similar labeling was absent in mlt1-1 cells (Figure 2E) and in mlt1::NIT1 insertion mutant cells (Materials and Methods, Figure S1 in supplementary material) [Pazour et al., 1995]. Specific anti- MLT1 labeling was not associated with the basal bodies or non-rootlet microtubules. These data indicate that MLT1 is uniquely associated with D4 rootlet microtubules. Other than components of the eyespot, MLT1 is the only known Chlamydomonas protein that is distributed asymmetrically relative to the mother/daughter halves of the cell [Dutcher, 2003].

MLT1 may bind D4 microtubules directly. Similar to recently identified microtubule-binding proteins in Arabidopsis [Hamada et al., 2013], MLT1 is proline-rich, and contains three “basic islands,” stretches of sequence between 143 and 234 residues in length that are devoid of Glu or Asp residues and have predicted isoelectric points between 11.5 and 12.9 (Figure 2A). These basic regions may interact with the conserved, acidic C-terminal tail of tubulin, known to bind basic sequences in a variety of proteins [Bai et al., 2013; Bhogaraju et al., 2013; Gigant et al., 2014; Zach and Stohr, 2014; Wang et al., 2014b]. Based on this idea, a MLT1 gene was constructed in which all sixteen codons specifying Lys or Arg in the largest basic island (asterisk in Figure 2A) were changed to codons specifying Asp or Glu (Materials and Methods). The altered MLT1 gene restored normal phototaxis and eyespot localization to mlt1 cells (Table S2 in supplementary material), and MLT1 was observed along the D4 rootlet by IF in the cells of two phototaxis positive transformants (T.M., unpublished data). Thus, the largest basic island is not required for MLT1 function, perhaps because the three basic regions are functionally redundant.

Alternatively, MLT1 may associate with microtubules via unidentified MAPs. In interphase cells labeled with anti-MLT1 and anti-ChR1, the plus ends of the D4 rootlet microtubules extended beyond the photoreceptor patch, but MLT1 fluorescence did not (Figure 2D, Figure S2 in supplementary material). The specificity for the more anterior portion of the rootlet may reflect an interaction between MLT1 and a component(s) of the eyespot, such as the photoreceptors, or proteins involved in their localization.

MLT1 associates with the D4 rootlet prior to microtubule acetylation

During cell division, the daughter basal bodies and rootlets become mothers, the old eyespot disappears, and mature daughter basal bodies, daughter rootlets, and eyespots are formed anew in each of the mitotic progeny. To determine when MLT1 disassociates from the daughter-turned-mother four-membered rootlet and associates with the nascent D4, we analyzed MLT1 localization during sequential stages of cell division (Figure 3). Pre-prophase/prophase cells exhibited either very faint anti-MLT1 fluorescence along a single four-membered rootlet, or no detectable anti-MLT1 signal (Figure 3B). No specific MLT1 labeling was observed in late prophase cells in which the basal body pairs had separated and the four-membered rootlets formed the metaphase band, which defines the future division plane (Figure 3C) [Gaffal and el-gammal, 1990; Ehler et al., 1998]. Thus, the association between MLT1 and rootlet microtubules is lost prior to assembly of the mitotic spindle, most likely in response to pathways that regulate entry into mitosis. A recent, in-depth characterization of the Chlamydomonas phosphoproteome identified 22 phosphosites within MLT1 (Figure 2A) [Wang et al., 2014a], raising the possibility that the phosphorylation state of MLT1 regulates its association with the D4 rootlet.

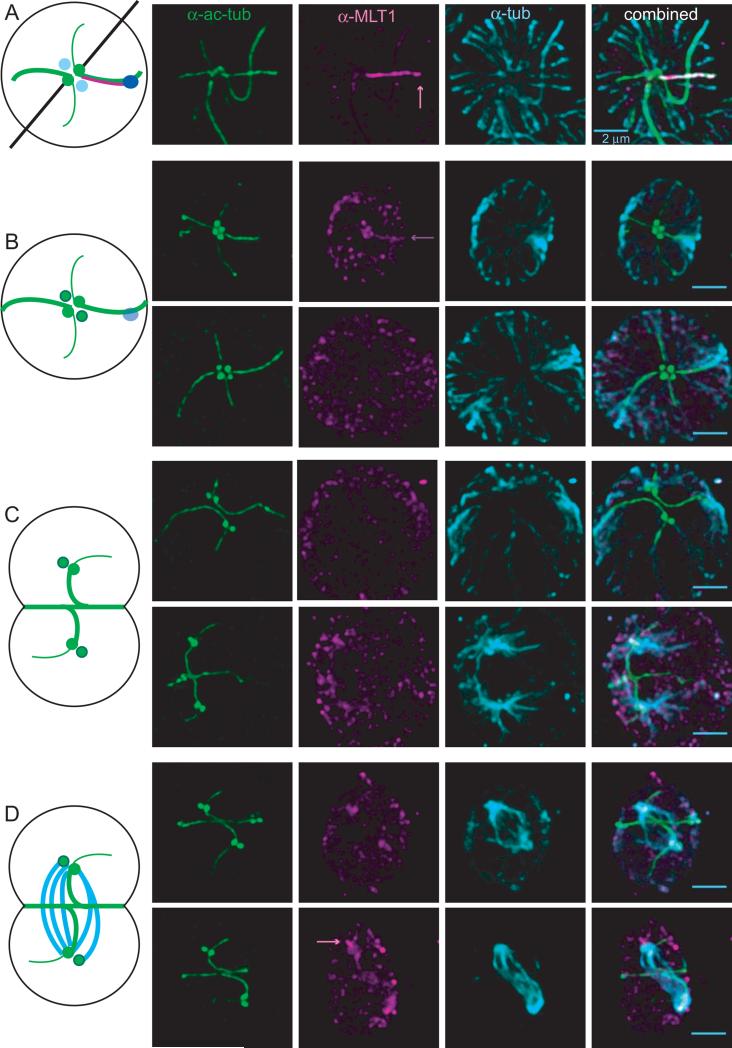

Figure 3. MLT1 localization during cell division.

Illustrations of the basal bodies and major microtubule-containing structures throughout Chlamydomonas cell division are shown to the left of IF images of wild-type cells labeled with anti-Ac-tub, anti-MLT1, and anti-tub. A legend for the diagrams is at the bottom of the figure. Scale bars = 2 μm. (A) An interphase cell with two mature basal bodies, flagella, and MLT1 immunoreactivity along a single acetylated microtubule rootlet (arrow). (B) Two representative cells in pre-prophase/prophase that were aflagellate and had two pairs of basal bodies. Faint anti-MLT1 labeling of a single rootlet (arrow) was often observed. (C) Two representative cells in prophase in which the basal body pairs had separated and developing spindle microtubules are associated with each basal body pair, but the mature mitotic spindle had not assembled. Specific anti-MLT1 labeling was not observed. (D) Two representative cells in which the mitotic spindle had assembled, indicative of metaphase (top) or anaphase (bottom). Specific anti-MLT1 labeling was not present in most metaphase/anaphase cells, but occasionally a small aggregation of MLT1 was observed near the daughter basal body (arrow). (E) Two cells in telophase or early cytokinesis in which the mitotic spindle had been disassembled and microtubules had polymerized at the division plane defined by the four-membered microtubule rootlets associated with the mother basal bodies. Anti-MLT1 labeling of the newly assembled but unacetylated D4 rootlet was consistently observed. (F and G) Three representative groups of daughter cells during later stages of cytokinesis when the flagella and the eyespot begin to assemble; two pairs of cells derived from a single mother by two successive divisions are pictured in the top row. The nascent D4 rootlets (green arrows) were acetylated in three of the four pairs of sister cells, and all of the D4 rootlets were labeled with anti-MLT1.

In metaphase/anaphase cells, identified by the presence of the mitotic spindle, MLT1 was observed only rarely as a very small, new accumulation adjacent to the daughter basal body (Figure 3D, bottom cell). Nascent D4 rootlet microtubules were not clearly identifiable in these cells, but their fluorescence may have been obscured by the overwhelming staining of the spindle microtubules. As previous structural studies have shown that newly polymerized daughter rootlets are present in metaphase cells [Gaffal, 1988; O'Toole and Dutcher, 2014], we favor the hypothesis that these nascent microtubules provide a platform for MLT1 accumulation. Alternatively, MLT1 may localize near the basal bodies and/or form filaments independently of microtubules, though the primary sequence of MLT1 shows no obvious similarities to known filament-forming proteins [e.g. Lechtreck and Melkonian, 1998; Kato et al., 2012].

MLT1 was consistently observed along the nascent D4 rootlet in cells in late mitosis/cytokinesis (Figures 3E and 3F), regardless of whether the microtubules had been acetylated. Rootlet microtubule polymerization and MLT1 association prior to acetylation is consistent with recent data suggestive that acetylation levels are a function of microtubule life-time, and acetylation appears minutes to hours after microtubule polymerization [Szyk et al., 2014]. As significant accumulation of the photoreceptors and EYE2 at the nascent eyespot occurs within the same time frame as rootlet acetylation [Mittelmeier et al., 2013], prior association of MLT1 with the rootlet is consistent with the hypothesis that MLT1 promotes directed movement of the photoreceptors.

The low-complexity, leucine-rich MLT2 protein is required for MLT1 expression or stability

Similar to mlt1 cells, mlt2 mutant cells have multiple eyespots, but the mlt2 phenotype is distinguishable from that of mlt1 because eyespots are more numerous, more disorganized and often mis-localized to the posterior half of the cell (Boyd et al., 2011b). Western blot analysis of whole-cell protein from two mlt2 out-crossed progeny (Materials and Methods) indicated that MLT1 is not stable and/or expressed in mlt2 cells (Figure 4A and Figure S1 in supplementary material). This result was confirmed by IF of mlt2 mutant cells (Figure 4B). Whole genome sequencing of the mlt2 genome [Dutcher et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013] revealed a 6 bp (two residue) in-frame deletion in Cre12.g501150 (Table S1 in supplementary material). This deletion is the only mutation within 1.0 Mbp of MLT1 (Materials and Methods), consistent with mapping data indicating that mlt2 is within 0.5 map unit of mlt1 [Boyd et al., 2011b]. The predicted MLT2 product is a 979 residue low-complexity protein (54% of the residues are Ala, Gly, Ser or Leu) with seven leucine-rich repeats in the N-terminal half. The mlt2 deletion removes codons for V413 and E414 between repeats 5 and 6. Though the wild-type MLT2 protein may be required for MLT1 transcription or for translation of the MLT1 protein, we favor the hypothesis that MLT2 is required for the association of MLT1 with the D4 rootlet, and without this association, the MLT1 protein is degraded. Understanding how MLT1 and MLT2 interact with each other and with microtubules will instruct studies of other microtubule-based systems that establish cell organization.

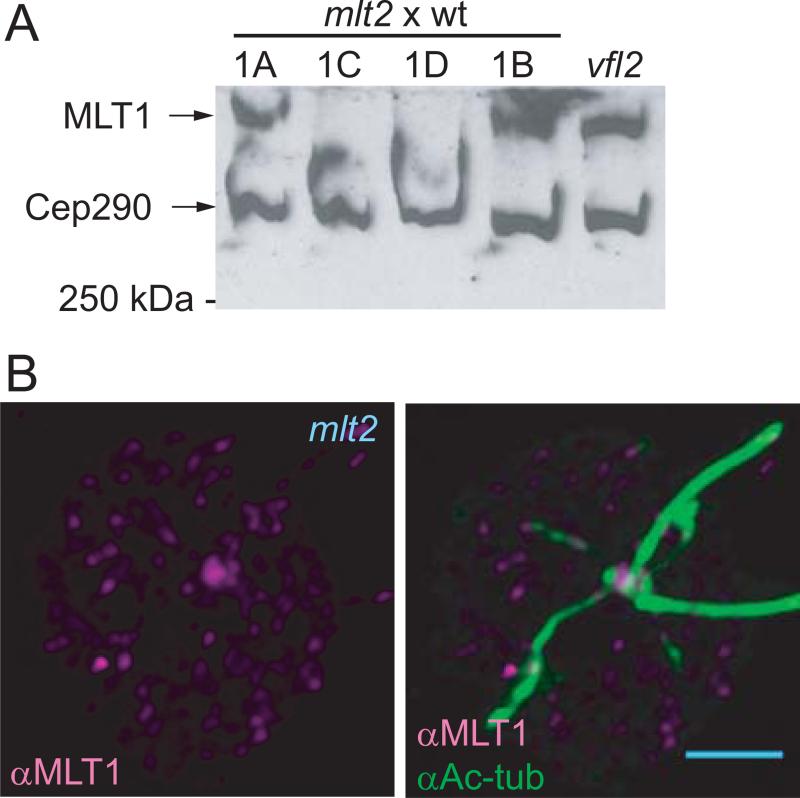

Figure 4. MLT1 is not detectable in mlt2 mutant cells.

(A) Western blot of whole cell protein separated by 5% SDS-PAGE probed with anti-MLT1 and anti-CEP290 [Craige et al., 2010]. The location of the 250 kDa size marker is indicated. Strains 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D were derived from a single tetrad obtained following two out-crosses of the original mlt2-1 mutant to wild-type strain 137c. Progeny 1A and 1B were phenotypically wild-type and contained the wild-type MLT2 genomic sequence, while 1C and 1D were multi-eyed and contained the 6 bp deletion identified in mlt2-1 cells (Materials and Methods and Table S1 in supplementary material). Whole cell protein from vfl2 mutant cells was used as a positive control. The entire length of the blot is shown in Figure S1 in supplementary material. (B) IF image of a mlt2 mutant cell labeled with anti-MLT1 and anti-Ac-tub. Only non-specific labeling with anti-MLT1 was observed. Scale bar = 2 μm.

Basal body organization affects MLT1 localization

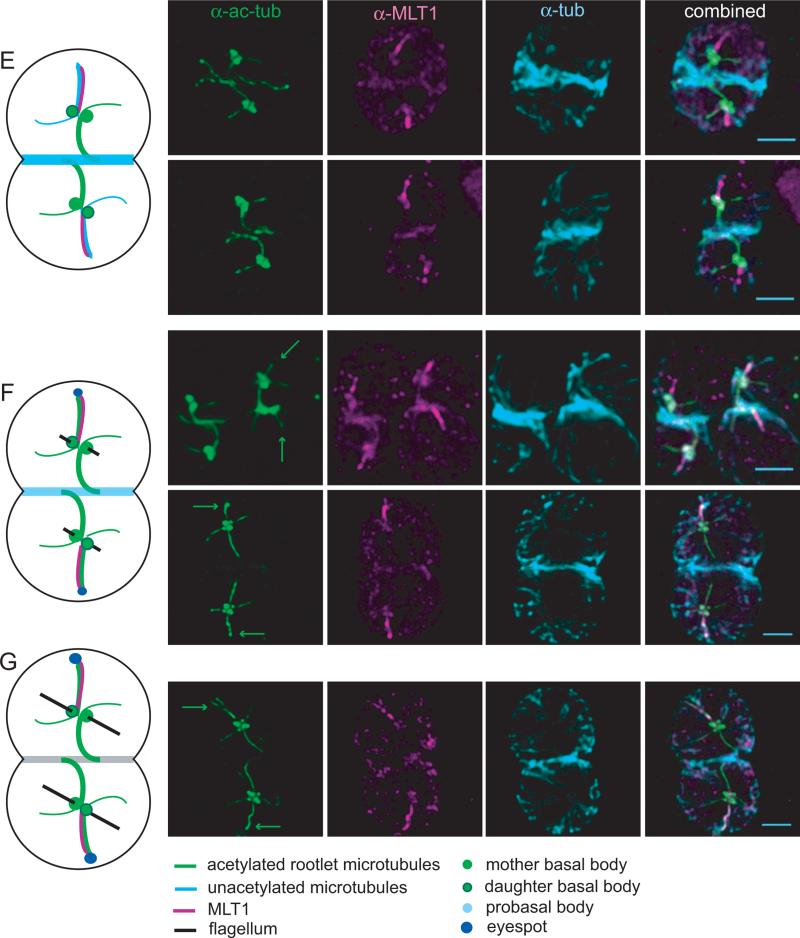

The four microtubule rootlets extend from the region between the mother and daughter basal bodies, just below the distal fibers that connect the basal bodies to one another [Goodenough and Weiss, 1978; Geimer and Melkonian, 2004; O'Toole and Dutcher, 2014]. To determine whether the association between MLT1 and the D4 rootlet is dependent on basal body organization, we examined MLT1 localization in vfl2-220 cells which have a missense mutation in the Chlamydomonas gene encoding centrin (Figure 5) [Kuchka and Jarvik, 1982; Taillon et al., 1992]. Centrin is a major component of fibrous structures associated with the basal bodies, including the distal connecting fibers, which hold the basal bodies together. Centrin mutations cause basal body mis-localization and mis-segregation, leading to the variable flagellar number phenotype for which the vfl2-220 mutant is named [Wright et al., 1985; Wright et al., 1989; Koblenz et al., 2003; Geimer and Melkonian, 2005]. In an analysis of 27 vfl2 cells with only two flagella (and presumably only two basal bodies) and at least 3 visible rootlets that could be viewed from the flagellar pole, 19 had two MLT1-labeled rootlets (Figure 5A), and one cell had three. Though their exact origin and structure could not be definitively determined, both MLT1-associated rootlets always appeared to extend from a single basal body.

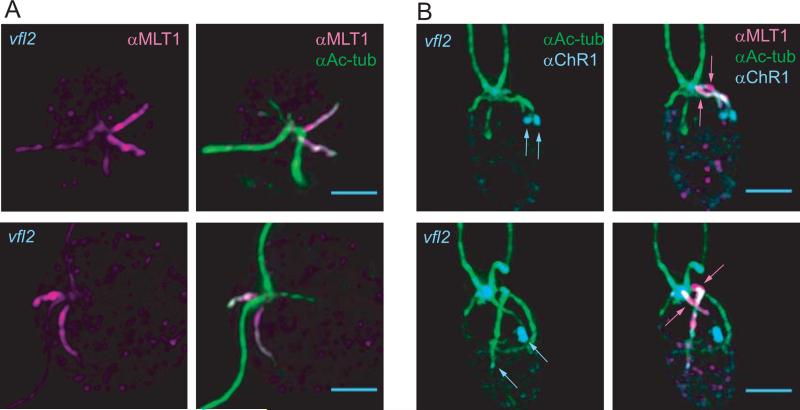

Figure 5. MLT1 specificity is lost in a centrin mutant.

IF images of vfl2 mutant cells labeled with anti-MLT1 and anti-Ac-tub alone (A), or in conjunction with anti-ChR1 (B). Anti-MLT1 immunoreactivity was observed on more than one rootlet in 20 of 27 vfl2 cells with two flagella and ≥ 3 rootlets. Scale bars = 2 μm.

To determine whether the association of MLT1 with non-D4 microtubule rootlets leads to ectopic patches of photoreceptor, vfl2 cells were labeled with both anti-MLT1 and anti-ChR1 (Figure 5B). In six of 14 cells with two flagella and two MLT1-labeled rootlets, both MLT1-labeled rootlets were associated with a ChR1 patch. Often, one of the ChR1 patches was extremely small, raising the possibility that some photoreceptor was associated with the additional MLT1-associated rootlet in a higher percentage of the cells. Together, the data are consistent with the hypothesis that MLT1 interacts with the photoreceptors and/or trafficking proteins and with rootlet microtubules to promote photoreceptor localization. Mis-localization of MLT1 in vfl2 cells could be a direct consequence of compromised centrin function; in wild-type cells, a patch of centrin observed near the anterior end of the D2 rootlet microtubules may limit MLT1 accessibility [Geimer and Melkonian, 2005]. Alternatively, correct localization of MLT1 and, therefore, of the eyespot photoreceptors may depend on one or more of the basal body-associated structures that are reduced or absent in cells lacking centrin. Understanding how MLT1 specificity is achieved will add molecular details to models describing how basal body asymmetries lead to cellular asymmetries.

Materials and Methods

Chlamydomonas strains and growth

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strains were maintained at 25°C on solid Tris-acetate-phosphate (TAP) medium [Harris et al., 2009]. For phototaxis assays, Western blot analysis of whole-cell protein, or immunofluorescence labeling of interphase cells, strains were grown at 25°C in liquid M medium (no acetate) [Mittelmeier et al., 2011] in constant light. For the analysis of MLT1 localization during cell division, cells were synchronized on solid TAP under a 12:12 light:dark regimen and harvested after one hour in the dark. The following strains are available through the Chlamydomonas Resource Center (University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN; chalmycollection.org): wild-type (wt, CC-125, 137c mt+), mlt1 (CC-4304, mlt1-1 mt+), and vfl2 (vfl2-220 mt+, CC-2530) which carries an E101K mutation in the gene encoding centrin [Taillon et al., 1992]. The single-eyed mlt1::MLT1 strain (Figure 2F) was obtained following phenotypic rescue of mlt1-1 with the 13.7 kb MLT1 genomic sequence (described below). The multi-eyed strain K16 (mlt1::NIT1, Figure S1 in supplementary material) was identified in a screen for phototaxis defective strains following insertional mutagenesis with NIT1 genomic sequence [Pazour et al., 1995]. Following mating of a K16 arg2 strain to mlt1-1 arg7, all prototrophic diploids examined (n = 10) retained the multi-eyed phenotype, indicating that K16 is a mlt1 allele (C. Dieckmann, unpublished data).

Identification of causative mutations in mlt1-1 and mlt2-1

Isolation, phenotypic characterization, and genetic mapping of the mlt1-1 and mlt2-1 mutant strains have been described [Lamb et al., 1999; Mittelmeier et al., 2011; Boyd et al., 2011a; Boyd et al., 2011b]. The lesions in both strains were identified by pair-ended 101 bp whole-genome sequencing (Table S1 in supplementary material) [Dutcher et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013]. With 43× sequencing coverage, 68950 SNPs/short indels found in mlt1-1 were compared to the 2.5 million SNP/short indel library found in 16 other Chlamydomonas strains. 28831 SNPs/short indels that are unique to mlt1-1 remained. Changes within the non-coding regions and reads that have Phred quality scores lower than 100 were eliminated using SnpEff [Cingolani et al., 2012]. Previous genetic mapping indicated that mlt1-1 is ~0.75 map unit away from eye2, which is located at position ~2.1 Mb on chromosome 12. Only one change was found in this region: a nonsense mutation at codon 1131 of the predicted reading frame of Cre12.g509850 (CAA → TAA). In the mlt2-1 strain, 43× sequencing coverage and SNP/short indel library comparison led to identification of 1693 SNPs/short indels that are unique to this mutant strain. Previous genetic analyses indicated that while mlt1-1 and mlt2-1 complement one another, they are only ~0.5 map unit apart on chromosome 12 [Boyd et al., 2011b]. Only one mutation was identified within 1.0 Mbp of mlt1-1: a 6 bp deletion of codons 413 and 414 of the predicted reading frame of Cre12.g501150. The two other mutations identified on chromosome 12 were ~2.8 and ~3.9 Mbp from mlt1-1, inconsistent with the mapping data for the mlt2-1 mutation. The MLT1 and MLT2 genomic and predicted protein sequences can be viewed using the Cre*.* numbers in the “keyword search” tool of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii v5.5 genome at the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) Phytozome portal (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html). Two out-crosses of mlt1-1 to wild-type strain 137c yielded multi-eyed strains mlt1-1-1D and mlt1-1-4B (Figure S1 in supplementary material). Both strains carried the Q1131STOP lesion. Likewise, two out-crosses of strain mlt2-1 to 137c yielded mlt2-1-1C and mlt2-1-1D (Figure 4A), which had both the mlt2 phenotype and the 6 bp deletion. In all crosses, the multi-eyed phenotype segregated 2:2.

Rescue of the mlt1 mutant phenotype

Cre12.g509850 extends from the predicted beginning of the 5'UTR on chromosome 12 at position 2,044,806 to the end of the 3'UTR at position 2,056,067. Phenotypic rescue of mlt1-1 by Cre12.g509850 sequence is summarized in Table S2 in supplementary material. Briefly, fragments of Chlamydomonas genomic sequence ligated to pARG7.8cos [Purton and Rochaix, 1995] were used to transform a mlt1-1, arg7-8 strain to arginine prototrophy (Arg+) by electroporation (Supplementary methods). Arg+ transformants were screened for the ability to phototax and eyespot phenotype. The multi-eyed phenotype was rescued by 13.7 kb or 11.3 kb sequences covering the predicted MLT1 gene. An 8.0 kb sequence lacking the C-terminal portion of the predicted coding sequence failed to rescue the mutant phenotype.

To construct pArg12BE/2DE, in which the 16 codons specifying Lys or Arg within the largest basic island (asterisk in Figure 2A) were changed to codons specifying Asp or Glu, altered sequence from the SmaI site at 12: 2,050,873 to the BlpI site at 12: 2,051,650 was synthesized (Genewiz, Inc., South Plainfield, NJ) and used to replace the corresponding sequence in pArg12BE. The mlt1-1 phenotype was rescued by pArg12BE/2DE (Table S2 in supplementary material).

Production of anti-MLT1

Sequence coding for MLT1 residues 2648 through 2759 (Figure 2A), which includes sequence that is similar to a predicted Volvox carteri protein (JGI ID 8849), was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli (DNA 2.0, Inc., Menlo Park, CA) and ligated in-frame to TrpE coding sequence using the BamHI site in the pATH1 vector [Koerner et al., 1991]. TrpE-MLT1 fusion protein expression was induced in E. coli as described [Koerner et al. 1991] and separated from other E. coli proteins by 10% SDS-PAGE. The portion of the gel containing the fusion protein was sent to Pacific Immunology Corp. (Ramona, CA) for the production of rabbit antiserum. For affinity purification of anti-MLT1, TrpE-MLT1 was transferred from a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel to 3 cm2 of PVDF membrane, which was then incubated with 0.4 ml of antiserum for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). The membrane was washed several times with PBS (123.0 mM NaCl, 10.4 mM Na2HPO4, 3.2 mM KH2PO4) before eluting the antibodies in three 150 μl, 30 second washes with 5 mM glycine, 150 mM NaCl. Each eluate was immediately neutralized with 50 μl of 0.5 M NaPO4, pH = 8.0.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were harvested from 0.2 ml of an overnight culture or from solid medium using a toothpick, transferred to 50 μl of autolysin [Harris et al., 2009], and 10 μl were spotted onto coverslips and incubated in a humid chamber at RT for 30 minutes (min). The cells were fixed in −20°C methanol for 30 seconds, and then air-dried. The fixed cells were rehydrated in block buffer (PBS, 1% BSA) for 30 min, then in block buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at RT. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C in block buffer containing 1:50 affinity purified polyclonal anti-MLT1 plus 1:50 anti-acetylated α-tubulin clone 6-11B-1 IgG2b (α-Ac-tub) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX) (Piperno and Fuller, 1985). Some experiments also included 1:50 anti-α-tubulin clone DM1A IgG1 (α-tub) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX). Cells were washed with block buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20, incubated for 2 hours at RT in block buffer containing 1:1000 dilutions of Alexa fluor-conjugated antibodies directed against rabbit IgG, mouse IgG2b, or mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), then washed again. For experiments including polyclonal anti-ChR1 [Berthold et al., 2008], the antibody was directly conjugated to Alexa fluor 594 using the Xenon IgG labeling kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) and applied to the cells after incubation with secondary antibodies. The labeled cells were washed thoroughly and coverslipped with Mowiol mounting medium prepared as described [Mittelmeier et al., 2013] which was allowed to harden for at least 24 hours before imaging.

Immunofluorescence was viewed using a DeltaVision Elite microscope (Applied Precision, a GE Healthcare Company, Issaquah, WA) with an Olympus 100× plan apo NA 1.4 objective plus a 1.6× optivar and appropriate filter sets. Images were captured with a pco.edge sCMOS camera (Kelheim, Germany). Z-series datasets were collected at a step size of 0.2 μm. Post-acquisition deconvolution was performed using SoftWorx software (Applied Precision, LLC, Issaquah, WA).

Western blot analysis

Cells from 2.0 ml of a liquid culture at 2.0 × 106 cells/ml were harvested, resuspended in 200 μl of 4× Laemmli buffer (250 mM Tris-Cl (pH=6.8), 40% glycerol, 20% β-mercaptoethanol, 8% SDS, 0.024% bromophenol blue) with protease inhibitors (5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1.0 mM PMSF) and heated at 100°C for 5 min. 40 μl of each sample were electrophoresed through 5% polyacrylamide-SDS gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using standard techniques. The membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dried milk in TBS-T (10 mM Tris-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween-20) for 1 hour at RT, probed overnight at 4°C with either 1:200 affinity purified anti-MLT1 or 1:1000 anti-CEP290 [Craige et al., 2010] in block buffer, washed in TBS-T, and probed with 1:10,000 horse radish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific, Rockford IL) in block. Following TBS-T washes, the blots were incubated in SuperSignal Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) for 1 min and exposed to ECL Hyperfilm (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Figure production

To produce a final micrographic image, ImageJ was used to collapse 6 to 12 Z-series images from a single channel, merge images from different channels, and add false color. Pixel value histograms were adjusted using either ‘brightness and contrast’ in ImageJ or ‘levels’ in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). Adobe Photoshop was used to add scale bars, crop images, and adjust image size. Images, text, and diagrams were assembled in Adobe Illustrator v11.0.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Susan Dutcher for providing access to whole genome sequencing of the mlt1-1 and mlt2-1 strains and for assistance with data analysis. Dr. Branch Craige and Dr. George Witman generously provided the anti-CEP290 polyclonal antibody, and Dr. Gregory Pazour and Dr. George Witman provided strain K16. Technical assistance with the microscopy was given freely by Patty Jansma and Dr. Ross Buchan. Dr. Huawen Lin, responsible for whole-genome sequencing of mlt1-1 and mlt2-1 and analysis of that data, was supported by NIH GM32843 awarded to Dr. Susan Dutcher. The majority of the work presented here was supported by National Science Foundation award MCB-1157795 to C. L. D.

References

- Bai X, Bowen JR, Knox TK, Zhou K, Pendziwiat M, Kuhlenbaumer G, Sindelar CV, Spiliotis ET. Novel septin 9 repeat motifs altered in neuralgic amyotrophy bind and bundle microtubules. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:895–905. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold P, Tsunoda SP, Ernst OP, Mages W, Gradmann D, Hegemann P. Channelrhodopsin-1 initiates phototaxis and photophobic responses in Chlamydomonas by immediate light-induced depolarization. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1665–1677. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.057919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhogaraju S, Cajanek L, Fort C, Blisnick T, Weber K, Taschner M, Mizuno N, Lamla S, Bastin P, Nigg EA, Lorentzen E. Molecular basis of tubulin transport within the cilium by IFT74 and IFT81. Science. 2013;341:1009–1012. doi: 10.1126/science.1240985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JS, Gray MM, Thompson MD, Horst CJ, Dieckmann CL. The daughter four-membered microtubule rootlet determines anterior-posterior positioning of the eyespot in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken ) 2011a;68:459–469. doi: 10.1002/cm.20524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JS, Lamb MR, Dieckmann CL. Miniature- and multiple-eyespot loci in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii define new modulators of eyespot photoreception and assembly. G3 (Bethesda) 2011b;1:489–498. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. Basal body and flagellar development during the vegetative cell cycle and the sexual cycle of Chlamydomonas reinhardii. J Cell Sci. 1974;16:529–556. doi: 10.1242/jcs.16.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craige B, Tsao CC, Diener DR, Hou Y, Lechtreck KF, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. CEP290 tethers flagellar transition zone microtubules to the membrane and regulates flagellar protein content. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:927–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher SK. Elucidation of basal body and centriole functions in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Traffic. 2003;4:443–451. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher SK, Li L, Lin H, Meyer L, Giddings TH, Jr., Kwan AL, Lewis BL. Whole-genome sequencing to identify mutants and polymorphisms in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. G3 (Bethesda) 2012;2:15–22. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehler L, Dutcher SK. Pharmacological and genetic evidence for a role of rootlet and phycoplast microtubules in the positioning and assembly of cleavage furrows in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1998;40:193–207. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)40:2<193::AID-CM8>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel BD, Schaffer M, Cuellar LK, Villa E, Plitzko J, Baumeister W. Native architecture of the Chlamydomonas chloroplast revealed by in situ cryo-electron tomography. eLIfe. 2015;4:e04889. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffal KP. The basal body-root complex of Chlamydomonas-reinhardtii during mitosis. Protoplasma. 1988;143:118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffal KP, el-gammal S. Elucidation of the enigma of the metaphase band of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Protoplasma. 1990;156:139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Geimer S, Melkonian M. The ultrastructure of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii basal apparatus: identification of an early marker of radial asymmetry inherent in the basal body. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2663–2674. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geimer S, Melkonian M. Centrin scaffold in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii revealed by immunoelectron microscopy. Euk Cell. 2005;4:1253–1263. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.7.1253-1263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigant B, Landrieu I, Fauquant C, Barbier P, Huvent I, Wieruszeski JM, Knossow M, Lippens G. Mechanism of tau-promoted microtubule assembly as probed by NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:12615–12623. doi: 10.1021/ja504864m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M. The 3Ms of central spindle assembly: microtubules, motors and MAPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough UW, Weiss RL. Interrelationships between microtubules, a striated fiber, and the gametic mating structure of Chlamydomonas reinhardi. J Cell Biol. 1978;76:430–438. doi: 10.1083/jcb.76.2.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RR. The basal bodies of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Formation from probasal bodies, isolation, and partial characterization. J Cell Biol. 1975;65:65–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.65.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T. Microtubule organization and microtubule-associated proteins in plant cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2014;312:1–52. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800178-3.00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T, Nagasaki-Takeuchi N, Kato T, Fujiwara M, Sonobe S, Fukao Y, Hashimoto T. Purification and characterization of novel microtubule-associated proteins from Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:1804–1816. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.225607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris E, Stern D, Witman G. The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook. Elsevier, Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes P, Varga V, Olego-Fernandez S, Sunter J, Ginger ML, Gull K. Modulation of a cytoskeletal calpain-like protein induces major transitions in trypanosome morphology. J Cell Biol. 2014;206:377–384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JA, Dutcher SK. Cellular asymmetry in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Cell Sci. 1989;94(Pt 2):273–285. doi: 10.1242/jcs.94.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Han TW, Xie S, Shi K, Du X, Wu LC, Mirzaei H, Goldsmith EJ, Longgood J, Pei J, Grishin NV, Frantz DE, Schneider JW, Chen S, Li L, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg D, Tycko R, McKnight SL. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: low complexity sequence domains form dynamic fibers within hydrogels. Cell. 2012;149:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblenz B, Schoppmeier J, Grunow A, Lechtreck KF. Centrin deficiency in Chlamydomonas causes defects in basal body replication, segregation and maturation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2635–2646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner TJ, Hill JE, Myers AM, Tzagoloff A. High-expression vectors with multiple cloning sites for construction of trpE fusion genes: pATH vectors. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:477–490. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94036-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreimer G. The green algal eyespot apparatus: a primordial visual system and more? Curr Genet. 2009;55:19–43. doi: 10.1007/s00294-008-0224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchka MR, Jarvik JW. Analysis of flagellar size control using a mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii with a variable number of flagella. J Cell Biol. 1982;92:170–175. doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb MR, Dutcher SK, Worley CK, Dieckmann CL. Eyespot-assembly mutants in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics. 1999;153:721–729. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck K-F, Melkonian M. SF-assemblin, striated fibers, and segmented coiled coil proteins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1998;41:289–296. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)41:4<289::AID-CM2>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDizet M, Piperno G. Cytoplasmic microtubules containing acetylated alpha-tubulin in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: spatial arrangement and properties. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:13–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Miller ML, Granas DM, Dutcher SK. Whole genome sequencing identifies a deletion in protein phosphatase 2A that affects its stability and localization in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WF. Centriole asymmetry determines algal cell geometry. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:632–637. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelmeier TM, Boyd JS, Lamb MR, Dieckmann CL. Asymmetric properties of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cytoskeleton direct rhodopsin photoreceptor localization. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:741–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelmeier TM, Thompson MD, Ozturk E, Dieckmann CL. Independent localization of plasma membrane and chloroplast components during eyespot assembly. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12:1258–1270. doi: 10.1128/EC.00111-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole ET, Dutcher SK. Site-specific basal body duplication in Chlamydomonas. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2014;71:108–118. doi: 10.1002/cm.21155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole ET, Giddings TH, McIntosh JR, Dutcher SK. Three-dimensional organization of basal bodies from wild-type and delta-tubulin deletion strains of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2999–3012. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour GJ, Sineshchekov OA, Witman GB. Mutational analysis of the phototransduction pathway of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:427–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno G, Fuller MT. Monoclonal antibodies specific for an acetylated form of α-tubulin recognize the antigen in cilia and flagella from a variety of organisms. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2085–2094. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purton S, Rochaix J-D. Characterization of the ARG7 gene of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and its application to nuclear transformation. Eur J Phycol. 1995;30:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ringo DL. Flagellar motion and fine structure of flagellar apparatus in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1967;33:543–&. doi: 10.1083/jcb.33.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara A, Ando R, Sapir T, Tanaka T. Microtubule dynamics in neuronal morphogenesis. Open Biol. 2013;3:130061. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Gessner G, Luff M, Heiland I, Wagner V, Kaminski M, Geimer S, Eitzinger N, Reissenweber T, Voytsekh O, Fiedler M, Mittag M, Kreimer G. Proteomic analysis of the eyespot of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii provides novel insights into its components and tactic movements. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1908–1930. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimogawara K, Fujiwara S, Grossman A, Usada H. High-efficiency transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by electroporation. Genetics. 1998;148:1821–1928. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sineshchekov OA, Govorunova EG, Spudich JL. Photosensory functions of channelrhodopsins in native algal cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85:556–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struk S, Dhonukshe P. MAPs: cellular navigators for microtubule array orientations in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2014;33:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyk A, Deaconescu AM, Spector J, Goodman B, Valenstein ML, Ziolkowska NE, Kormendi V, Grigorieff N, Roll-Mecak A. Molecular basis for age-dependent microtubule acetylation by tubulin acetyltransferase. Cell. 2014;157:1405–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taillon BE, Adler SA, Suhan JP, Jarvik JW. Mutational analysis of centrin - an EF-hand protein associated with 3 distinct contractile fibers in the basal body apparatus of Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1613–1624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladar EK, Bayly RD, Sangoram AM, Scott MP, Axelrod JD. Microtubules enable the planar cell polarity of airway cilia. Curr Biol. 2012;22:2203–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Gau B, Slade WO, Juergens M, Li P, Hicks LM. The global phosphoproteome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveals complex organellar phosphorylation in the flagella and thylakoid membrane. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014a;13:2337–2353. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.038281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Crevenna AH, Kunze I, Mizuno N. Structural basis for the extended CAP-Gly domains of p150 (glued) binding to microtubules and the implication for tubulin dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014b;111:11347–11352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403135111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witman GB. Chlamydomonas phototaxis. Trends Cell Biol. 1993;3:403–408. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90091-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RL, Adler SA, Spanier JG, Jarvik JW. Nucleus-basal body connector in Chlamydomonas: evidence for a role in basal body segregation and against essential roles in mitosis or in determining cell polarity. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1989;14:516–526. doi: 10.1002/cm.970140409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RL, Salisbury J, Jarvik JW. A nucleus-basal body connector in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii that may function in basal body localization or segregation. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1903–1912. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.5.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zach F, Stohr H. FAM161A, a novel centrosomal-ciliary protein implicated in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;801:185–190. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3209-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.