Abstract

Upon nutrient limitation, budding yeasts like Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be induced to adopt alternate filament-like growth patterns called diploid pseudohyphal or invasive haploid growth. Here, we report a novel constitutive pseudohyphal growth state, sharing some characteristics with classic forms of filamentous growth, but differing in crucial aspects of morphology, growth conditions and genetic regulation. The constitutive pseudohyphal state is observed in fus3 mutants containing various septin assembly defects, which we refer to as sadF growth (septin assembly defect induced filamentation) to distinguish it from classic filamentation pathways. Similar to other filamentous states, sadF cultures comprise aggregated chains of highly elongated cells. Unlike the classic pathways, sadF growth occurs in liquid rich media, requiring neither starvation nor the key pseudohyphal proteins, Flo8p and Flo11p. Moreover sadF growth occurs in haploid strains of S288C genetic background, which normally cannot undergo pseudohyphal growth. The sadF cells undergo highly polarized bud growth during prolonged G2 delays dependent on Swe1p. They contain septin structures distinct from classical pseudo-hyphae and FM4-64 labeling at actively growing tips similar to the Spitzenkörper observed in true hyphal growth. The sadF growth state is induced by synergism between Kss1p-dependent signaling and septin assembly defects; mild disruption of mitotic septins activates Kss1p-dependent gene expression, which exacerbates the septin defects, leading to hyper-activation of Kss1p. Unlike classical pseudo-hyphal growth, sadF signaling requires Ste5, Ste4 and Ste18, the scaffold protein and G-protein β and γ subunits from the pheromone response pathway, respectively. A swe1 mutation largely abolished signaling, breaking the positive feedback that leads to amplification of sadF signaling. Taken together, our findings show that budding yeast can access a stable constitutive pseudohyphal growth state with very few genetic and regulatory changes.

Author Summary

Many pathogenic fungi alternate between unicellular and multicellular filamentous forms, which is often critical for host-cell attachment, tissue invasion, and virulence. Certain strains of the nonpathogenic budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are also capable of forming invasive pseudohyphal filaments in nutrient poor conditions, which has served as a model system for the study of filamentous fungal pathogens. Here, we show that the most commonly used laboratory strain, S288c, previously known as being non-filamentous, can adopt a permanent stable pseudohyphal growth phase even under rich growth conditions. Although some features are shared, the degree of filamentation, genetic requirements, cell cycle, and mechanism of regulation are distinct from the previously described forms of filamentous growth. Stable pseudohyphal growth arises as a result of only two mutations, neither of which causes pseudohyphal growth on their own. One mutation causes subtle defects in the mechanism of cell separation (septation), which activate intracellular signaling pathways that slow cell division and promote filamentation. Normally this pathway is kept in check by a related signaling protein. However, when the inhibitor is also defective, activation of the filamentation signaling pathway exacerbates the septation defects, which causes a synergistic hyper-activation of pseudohyphal growth. These findings expand our understanding of fungal pathogenesis mechanisms at the molecular level.

Introduction

Many fungal pathogens undergo a developmental transition from unicellular to multicellular filamentous forms that are important for the invasion of host tissue and virulence [1]. Certain strains of nonpathogenic Saccharomyces cerevisiae are also capable of developing filament-like growth under starvation conditions, which is thought to serve as a foraging mechanism. For example, diploid yeast cells starved for nitrogen exhibit pseudohyphal growth on solid agar medium [2]. Pseudohyphae consist of invasive filaments comprising chains of elongated cells that remain physically connected after cytokinesis, divide in a unipolar manner, and have an altered cell cycle to a prolonged budded period [2,3]. Haploid yeast undergoes a similar morphological transition called “haploid invasive growth” in response to glucose depletion. Under these conditions, haploid cells penetrate the agar, but do not become as elongated as cells in diploid pseudo-hyphal cells and do not form extensive filaments on the agar surface [4].

The regulation of the known patterns of dimorphic growth is complex, but requires at least two major signaling pathways, the filamentation mitogen activated protein kinase (fMAPK) and the nutrient-sensing cyclic AMP-protein kinase A (cAMP/PKA) pathway (reviewed by [5]). Both pathways coordinately upregulate FLO11, a cell surface flocculin; flo11 mutant cells fail to form chains or invade agar in both haploid and diploid yeast.

The fMAPK pathway includes several protein kinases, Ste20p, Ste11p, Ste7p, and the MAPK Kss1p, which act sequentially to activate the transcription factor Ste12p/Tec1p heterodimer and regulate expression of genes responsible for filamentous growth [5]. Several elements of the fMAPK cascade are also essential for the pheromone response pathway required for mating. However, activation of the MAPK for mating, Fus3p, blocks the filamentation program by down-regulating Kss1p and Tec1p [6,7]. Signal specificity is also provided by the Ste5p scaffold protein, which transduces pheromone signaling after recruitment to the G-protein β/γ dimer (Ste4p/Ste18p) at the plasma membrane. Ste5p is absolutely required for activating Fus3p [8], but is not required for the fMAPK pathway. Although upstream signaling events for the fMAPK pathway are not well understood, Ras2p GTPase and the plasma membrane-linked receptors, Msb2p and Sho1p have been reported to be implicated in fMAPK activation, along with Cdc42p, the rho GTPase that activates Ste20p [5].

Ras2p activates a second signal transduction pathway by stimulating adenylate cyclase and cAMP production [9]. Increased cAMP levels activates the Tpk2p catalytic subunits of PKA, which phosphorylates and displaces the repressor Sf1lp, activating the key filamentous transcription factor Flo8p [5]. Many commonly used laboratory strains, including S288C, the reference strain for the yeast genome project, carry a flo8 mutation and are unable to form pseudo-hyphal filaments or undergo haploid invasive growth [10]. A G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) called Gpr1p also appears to act upstream of adenylate cyclase, dependent on Gpa2p, a G-protein α subunit. Phospholipase Plc1p modulates the interaction of Gpa2p with Gpr1p [5].

Less clear are the cell biological mechanisms governing the morphological change to filamentous growth, as distinct from budding growth. It seems likely that at least three conditions must be met for cells to form filaments. First, individual cells must maintain a polarized pattern of growth, rather than the isotropic growth observed in budding cells. Second, because filamentous cells grow to much larger volumes than budding cells, they must alter the normal coupling between growth and mitosis. Finally, for cells to stay together as filaments, they must suppress the completion of septation to form long chains.

Cytokinesis, septation, and polarized growth are governed in part by a conserved family of proteins called septins. The yeast septins (Cdc3p, Cdc10, Cdc11p, Cdc12p and Shs1p) polymerize into membrane-associated filaments that form an ordered ring structure at the future budding site. During mitosis the septin ring expands into an hourglass-shaped collar that serves as a diffusion barrier and as a scaffold to direct a variety of cellular processes, including morphogenesis and bud site selection (reviewed by [11]). The formation of higher-ordered septin structures requires several post-translational modifications (reviewed by [12]). The protein kinases Elm1p, Gin4p and Cla4p promote proper septin assembly. Both Gin4p and Cla4p phosphorylate the septins and regulate the dynamics and organization of septin filaments [13,14]. Cla4p is also required for Gin4p activation [15] and recruitment to the bud neck and septins [13,16]. Elm1p directly phosphorylates Gin4p [17] and is required for mitotic hyper-phosphorylation of Cla4p [18]. In addition, genetic data suggests that each kinase functions in parallel to regulate septin behavior [16,19]. Proper organization of the septins at the bud-neck is critical for coupling morphogenesis and cell cycle progression (reviewed by [20]). Defects in septin assembly lead to accumulation of Swe1p, an inhibitory kinase of mitotic CDK. As a result, septin-defective cells, including elm1, gin4, and cla4 mutants, fail to switch from apical growth to isotropic growth, leading to formation of elongated buds.

We have identified a novel constitutive pseudohyphal growth phase of yeast distinct from the previously described pseudohyphal and haploid invasive growth patterns. Although some features are shared, many others are different, including the degree of filamentation, genetic requirements, and mechanism of regulation. Constitutive pseudohyphal growth arises from synergism between septin assembly defects and loss of Fus3p. The ease by which budding yeast can adopt a stable pseudohyphal growth state is consistent with recent findings that the transition from unicellular to filamentous growth requires relatively few regulatory changes.

Results

Identification and characterization of constitutive pseudo-hyphal growth

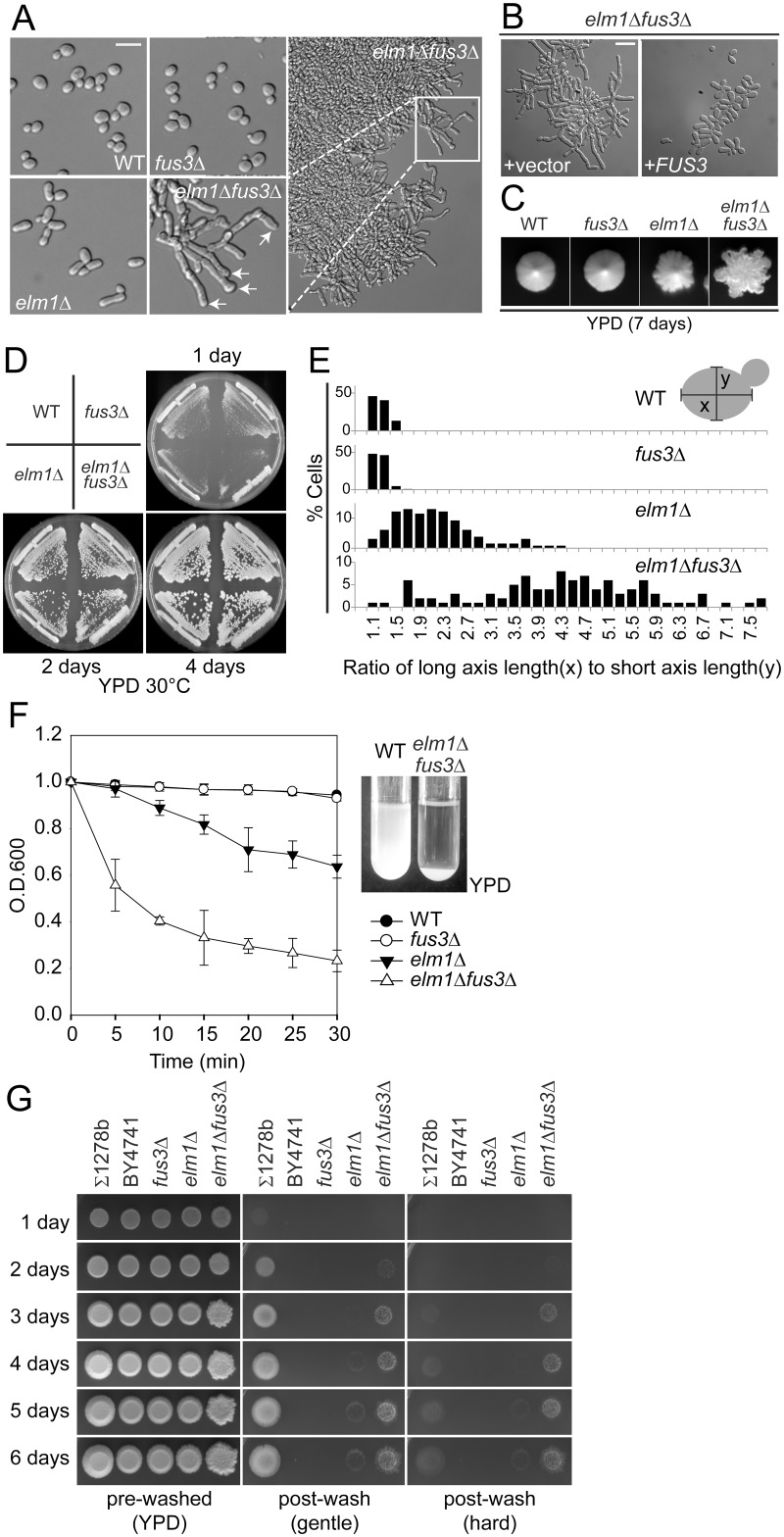

Strain BY4741, the reference strain for the yeast genome, is a haploid derived from the filamentation-deficient S288C background. In the course of routine strain construction, we observed that elm1Δ fus3Δ double mutants exhibited unusual colony and cell morphologies (Fig 1). ELM1 encodes a protein kinase that regulates septins and cytokinesis. The elm1Δ caused elongated buds and slightly rough colony morphology (Fig 1A and 1C). Fus3p is a pheromone-activated MAP kinase and functions during mating [21]. Although fus3Δ had no obvious effect on the cell or colony morphology in the wild-type (WT) background, combination with elm1Δ led to dramatic morphological changes (Fig 1A). The elm1Δ fus3Δ cells grew as large aggregates in liquid YPD medium, forming extensive filaments comprising chains of highly elongated cells. The abnormal morphology was completely reversed by a CEN plasmid carrying FUS3 (Fig 1B).

Fig 1. Filamentous growth of elm1Δ fus3Δ cells.

All of indicated strains (MY8092, 12158, 12886 and 12948) were BY4741-derivative haploids and grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C unless stated otherwise. (A) Arrows indicate the buds that emerge from the pole opposite previous division site. (B) elm1Δ fus3Δ (MY12948) harboring empty vector (MR1865) or pCEN-FUS3 (MR5048) were grown in liquid synthetic complete (SC) medium containing 2% glucose. (C) Cells were streaked for single cells on YPD plate at 30°C for 7 days, and representatives in a zone of low colony density were photographed. (D) Indicated cells (MY8092, 12158, 12886 and 12948) were streaked on YPD solid medium and incubated at 30°C. (E) The ratio of long axis (x) to short axis length (y) was expressed in a histogram. For example, 1.1 and 1.3 at the x-axis indicate the range from 1.00 to 1.19 and 1.20 to 1.39, respectively. (F) Flocculation assay was performed as described in Materials and methods. Data are representative of three independent experiments and expressed relative to WT. (G) Cells were spotted on YPD plate and grown at 30°C for 6 days. Haploid Σ1278b (MY13465) was used as a positive control of invasive growth. (A and B) Bar, 10 μm.

Colony morphology can be influenced both by growth conditions and by cellular morphology. Colonies of fus3Δ displayed a smooth circular outline with a lustrous surface, identical to WT (Fig 1C). The elm1Δ colonies exhibited a slightly notched outline (Fig 1C). In contrast, elm1Δ fus3Δ colonies were highly ruffled and rough-edged, with filaments extending beyond the perimeter of the colony (Fig 1C). Colonies of elm1Δ fus3Δ were comparable in size to WT, indicating that they grow with a similar rate as WT (Fig 1D).

The morphology of the elm1Δ fus3Δ cells resembled diploid pseudohyphal filaments; both cells are highly polarized and form extensive surface-spread filaments. However, the elm1Δ fus3Δ filaments are clearly distinct from pseudohyphal growth, which is restricted to diploid cells, occurs only on solid medium deficient in nitrogen, and requires FLO8 [2]. In contrast, the elm1Δ fus3Δ filaments formed from haploid cells, carrying a flo8 mutation, and grew stably in rich liquid media (YPD). Given these differences, and because of significant differences in regulation described later, we refer to the morphology observed in the elm1Δ fus3Δ mutant as “septin assembly defect induced filamentous” growth (sadF).

One major characteristic of sadF growth is the extreme elongation of the cells. In WT cells the ratio of the long axis to the short axis was 1.22 ±0.15 (n = 112), which was not affected by the fus3Δ (1.21 ±0.13, n = 106) (Fig 1E). The elm1Δ had a ratio of 2.15 ±0.67 (n = 132), consistent with their slight elongation. In contrast, elm1Δ fus3Δ was almost 4 times longer than WT (4.31 ±1.48, n = 101) (Fig 1E). Thus, the fus3Δ mutation greatly enhanced polarized cell growth of elm1Δ.

The elm1Δ fus3Δ strain grew in large multicellular clumps (Fig 1A), suggesting a high level of cell-cell adhesion. To assess the level of aggregation, we used a spectrophotometric assay to measure the rate at which cells settled out of liquid culture. Both WT and fus3Δ cultures showed very little decrease in optical density (Fig 1F) and the elm1Δ showed a slight decrease. In contrast, elm1Δ fus3Δ cells rapidly settled out of suspension, with a half-time less than 5 minutes; almost all settled by 15 minutes. Thus the fus3Δ mutation enhanced greatly cell-cell adhesion in elm1Δ.

Next, we examined if elm1Δ fus3Δ cells are able to penetrate solid growth media as do pseudohyphal diploids and invasive haploids. Non-adherent cells were easily washed off with a stream of water, after which two classes of cells remained: invasive cells and adherent non-invasive cells (Fig 1G, gentle post-wash). Adherent non-invasive cells can be removed by vigorous rubbing of the agar surface under running water (Fig 1G, hard post-wash). Haploid Σ1278b, a standard background for filamentous growth, began to penetrate the solid medium after 3 days, as a result of glucose depletion. In contrast, both WT haploid BY4741 and fus3Δ failed to invade even after prolonged growth (Fig 1G, hard post-wash). The elm1Δ strain exhibited very weak invasiveness (Fig 1G). Remarkably, agar penetration by elm1Δ was enhanced strongly by fus3Δ. Although elm1Δ fus3Δ surface cells were easily removed by gentle washing, showing that the strain is less adherent than Σ1278b (Fig 1G, gentle post-wash), a significant portion invaded the agar (Fig 1F, hard post-wash). Agar penetration began to be visible after 2 days and increased over time. These data suggest that elm1Δ fus3Δ pseudohyphal growth is more invasive, but less adherent, than haploid invasive growth.

Highly polarization and altered budding pattern in sadF growth

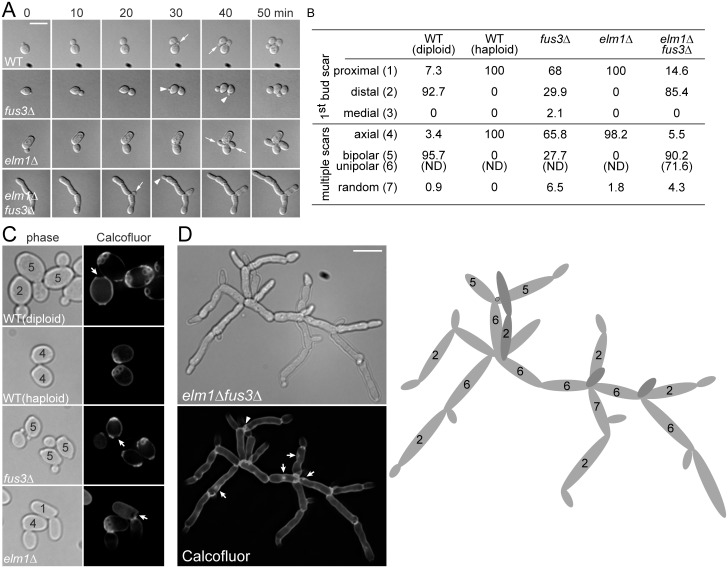

The reiteration of the axial budding pattern in haploids produces tight clusters of cells that form mounds on the surface of solid media ([22] and Fig 1C). In contrast, elm1Δ fus3Δ cells budded from the pole opposite the previous division site (distal pole, Fig 1A, arrows) and formed mats of branching chains of cells extending beyond the colony margin (Fig 1C). To characterize the elm1Δ fus3Δ growth pattern in detail, we used time lapse microscopy. Cells were sonicated lightly and applied to YPD agar pads. Because most elm1Δ fus3Δ cells are in large clumps, cells remaining in suspension were observed. Bud site selection was determined for all buds that emerged after the initial observation; none of the cells present at time zero was scored, as the previous division site could not always be determined. In all of 14 WT and 12 elm1Δ cells, the new buds emerged adjacent to the first mother/daughter bud site (proximal pole; Fig 2A). In contrast, in 11 elm1Δ fus3Δ cells the new buds emerged at the distal pole; in 10 cells they emerged at the proximal pole (Fig 2A). Surprisingly, even with fus3Δ, budding was not always axial (Fig 2A); 5 of 14 buds formed at the distal pole and 9 at the proximal pole (Fig 2A). These results show that Fus3p is required for the normal axial budding pattern and its loss induces the polar budding pattern that is critical for growth and extension of a filament [2].

Fig 2. Budding pattern of elm1Δ fus3Δ cells.

All of indicated strains (MY8092, 12158, 12886 and 12948) were BY4741-derivative haploids and grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C. S288C-derivative diploid (MY13411) was used as a positive control of bipolar budding. (A) Budding pattern was examined by time lapse microscopy as described in Materials and methods. Representative images are shown at 10-min interval. Arrows and arrow heads indicate the daughters that emerge adjacent or opposite to the preceding division site, respectively. (B) Cells were classified by number and distribution of bud scars. For each sample, more than 200 cells were counted and the score was expressed as a percentage. N.D, not determined. (C and D) Cells were stained with 0.1% calcofluor. The classified budding patterns are denoted as numbers that correspond to that of (B). (C) Arrows indicate birth scar. (D) Representative cluster of elm1Δ fus3Δ cells is shown with an interpretative drawing of the budding pattern (right). Arrow head (left) and black ring (drawing) indicate a bud scar. Arrows indicate abnormal chitin accumulations. (A, C, and D) Bar, 10 μm.

To further quantify the budding pattern, cells were stained with calcofluor white, which binds to chitin in the cell wall, most strongly at the bud scars (Fig 2B–2D). Cells with 1 bud scar were divided into three classes based on the position of the bud scar relative to the birth scar: (1) proximal, (2) distal, and (3) medial. Cells with 2 or more bud scars were divided into three classes: (4) axial, if all bud scars are adjacent at one end of the cell, (5) bipolar, if all bud scars are positioned at the distal pole or distributed between the proximal and distal pole, and (7) random, if one or more bud scars is positioned in the midsection. WT haploids always had the first bud scar proximal to their birth scar and multiple bud scars were clustered in a chain at one end of the cells. The elm1Δ haploids behaved like WT (Fig 2B and 2C). Consistent with the time-lapse microscopy, only 66% of the fus3Δ cells exhibited the axial budding pattern; in about 30% of cells the first bud was opposite the birth scar and 28% of cells with multiple bud scars showed bipolar budding (Fig 2B and 2C). As expected, WT diploids always budded in the bipolar mode (Fig 2B and 2C).

The elm1Δ fus3Δ filamentous aggregates could not be dispersed to single cells even by extensive sonication, suggesting that the cells remained strongly attached. Staining with calcofluor showed greatly enhanced staining over most of the cell wall except for the distal tips (Fig 2D), unlike WT in which staining was confined to bud scars and septa (Fig 2C). Although staining was observed at abnormal sites (arrows), most cells showed intense staining at the junction between cells, suggesting the presence of a complete septum (Fig 2D). Staining of the plasma membrane with the fluorescent styryl dye FM4-64 showed most bud necks had plasma membrane except where buds were growing at the end of cell chains (Fig 3E). These data suggest that although septum formation may be abnormal, the elongated cells do eventually complete cytokinesis. We conclude that chain formation is largely due to decreased abscission.

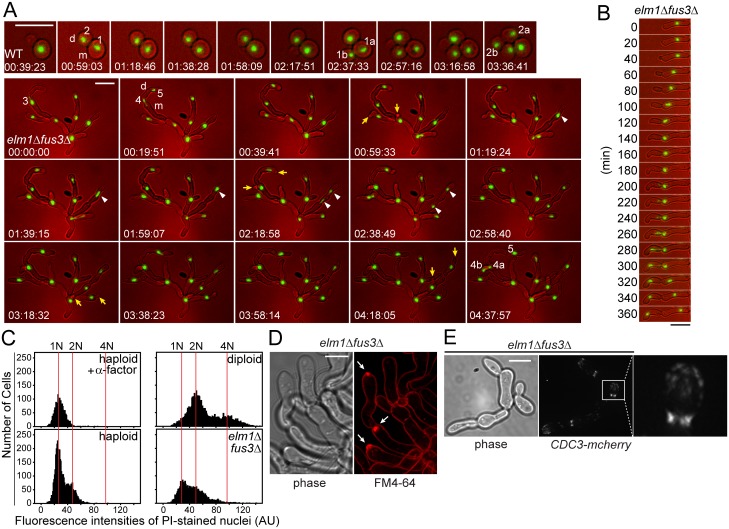

Fig 3. Cell biological characteristics of elm1Δ fus3Δ cells.

All cells were grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C. (A and B) The nuclei of indicated strains carrying HTB1-GFP (MY13817 and 13820) were examined by time lapse microscopy as described in Materials and methods. Representative images are shown at 20-min interval. (A) Sequential nuclear division is indicated by the number. For example, the nucleus #1 that had been just divided was segregated into two nuclei (1a and 1b) during the next round of cell cycle. Arrows indicate the daughter cells that emerge synchronously. Arrow heads show the nuclear division in mother cells. m, mother. d, daughter. (C) Indicated cells (MY8092, 12948 and MY13411) were stained with propidium iodide and their intensities were expressed in a histogram as described in Materials and methods. 10 μg/ml α-factor was treated to arrest cells in G1 with 1N DNA content. (D) elm1Δ fus3Δ (MY12948) were stained with FM4-64 to visualize the plasma membrane. Arrows indicate an intensive fluorescent accumulation, Spitzenkörper-like structure. Bar, 5 μm. (E) Indicated cells (MY13161 and 13264) were examined to visualize septin, Cdc3-mCherry. (A, B and E) Bar, 10 μm.

Analysis of the budding pattern of the smaller elm1Δ fus3Δ clusters supported the hypothesis that they are defective for cell separation. A representative cell is shown in Fig 2D with an interpretative drawing of the budding pattern. In this cluster, only one clear bud scar (arrow head and black ring in the carton) is visible, suggesting that very few cells have separated from the cell mass. Nevertheless, the branching pattern allows one to deduce the budding history. Most new buds (85%) were positioned at the distal pole and the bipolar budding pattern increased to 90%, compared to 28% of fus3Δ (Fig 2B–2D). Only 5.5% exhibited axial budding (Fig 2B and 2D). Importantly, among cells classed as “bipolar”, 72% exhibited a more polarized unipolar budding pattern (Fig 2B and 2D), a characteristic of diploid pseudohyphal growth in which new buds form only at the distal poles of both the mother and the daughter cells. Taken together, our data show that sadF growth is due to extreme cell elongation, coupled with to unipolar budding, resulting in extensive growth beyond the colony margin as seen in Fig 1C.

Cell biological characteristics of sadF growth

The filamentous nature of elm1Δ fus3Δ raises the question of how nuclear division is coupled to cell division, and whether the cells are multi-nucleate or uninucleate. To monitor cell cycle progression, we visualized the nucleus using GFP-tagged histone, Htb1p. WT displayed the typical asymmetric cell division in which a bud emerged on the mother prior to bud emergence on the daughter. The interval between two sequential nuclear divisions defines the cell cycle time. For WT (Fig 3A), the nucleus #1 in the mother (m) divided after about 1h 30min, while the nucleus #2 in the daughter (d) divided after about 2h 30min. Similar times were observed for other cells (1h 56 min ± 14, for the mother, n = 14; 3h 9 min ± 35, for daughters, n = 15). In contrast, elm1Δ fus3Δ cells commonly showed simultaneous bud emergence on both the mother and daughter (Fig 3A, arrows). The cell cycle was significantly longer and more variable, compared to WT. For example, after nucleus #3 divided into two nuclei, it took 4h 20min for nucleus #4 in the mother (m) to divide while nucleus #5 in the daughter (d) remained undivided over the time course (5h 30min). In 8 of 14 cells, the time between nuclear divisions was almost 3 times longer than WT (5h 33min ±48); in 6 cells the nucleus remained undivided by 8h.

In most elm1Δ fus3Δ cells, the nucleus was located near the bud neck just prior to division (Fig 3B), as in WT. When the bud emerged, a centrally located nucleus migrated close to the bud neck. The bud continued to grow apically until mitosis occurred and one daughter nucleus migrated into the daughter cell. Often, the nucleus retained its aberrant position, leading to division in the mother or daughter cell (Fig 3A, arrow heads). In these cases, one of the nuclei always moved into the mother or daughter cell, followed rapidly by formation of a septum. Thus, each segment in the filament contained a single nucleus. After nuclear separation, the nuclei remained in separate cell compartments, supporting the suggestion that complete septa have formed.

The slow nuclear cell division cycle might arise if DNA replication occurred without mitosis. We therefore examined the DNA content by quantitative fluorescence microscopy (fluorescence-activated cell sorting was not feasible with the filamentous cells). WT haploids arrested with α-factor yielded a single peak, which corresponds to 1N DNA content (Fig 3C). An asynchronously growing WT haploid strain was a mixture of 1N and 2N cells, with most cells 1N. Note that post-metaphase nuclei are 1N in this experiment. Similarly, an isogenic diploid yielded two unequal peaks corresponding to 2N and 4N (Fig 3C). The elm1Δ fus3Δ cells also had two peaks, coincident with 1N and 2N, with no peak at 4N, showing that these cells are haploid. However, a significantly higher fraction of the cells had 2N DNA content, indicating that many are paused in G2, consistent with a delay in nuclear division after replication. In spite of the dramatically slowed nuclear division cycle, the growth rate of elm1Δ fus3Δ was comparable to WT at 30°C (Fig 1D). Therefore, the continued elongation of cells in G1 and the extended G2 phase compensate for the reduced rate of cell division.

FM4-64 binds to the plasma membrane bilayer and only enters the cell via endocytosis. Unexpectedly, FM4-64 staining revealed discrete bright spots of fluorescence at the tips of growing filamentous cells and nascent branch points (Fig 3D, arrows). These bright spots are reminiscent of Spitzenkörper, which can be transiently visualized with endocytic FM4-64 and act as an organizing center to concentrate vesicles to the highly polarized, actively growing tips of hyphae in filamentous fungi [23]. Thus, as for filamentous fungi, pseudohyphal growth might be associated with a Spitzenkörper-like structure, consistent with highly polarized cell growth.

One of fundamental differences between pseudo and true hyphae is the septin cytoskeleton [24]. The dimorphic fungal pathogen C. albicans grows as budding yeast, but also forms both pseudo and true hyphae. During Candida budding, the septin structure is similar to that of Saccharomyces budding. However, the localization and organization of the septins are distinct during hyphal growth (rings, bars, and caps [24]). In hyphal development a band of longitudinal septin bars and a cap of septin form at the base or tip of germ tube respectively. Because elm1Δ fus3Δ cells showed one characteristic of true hyphae, a Spitzenkörper-like structure, we examined the septin organization, using Cdc3-mCherry (Fig 3E). Strikingly, septins in the elm1Δ fus3Δ assembled rings composed of discrete and parallel septin bars at the bud neck, and were also found as a diffuse cap at the growing tip as observed during Candida hyphal growth. These results further indicate that the pseudohyphae of elm1Δ fus3Δ are distinct from classical pseudohyphae.

Induction of pseudohyphal growth by disruption of mitotic septin assembly

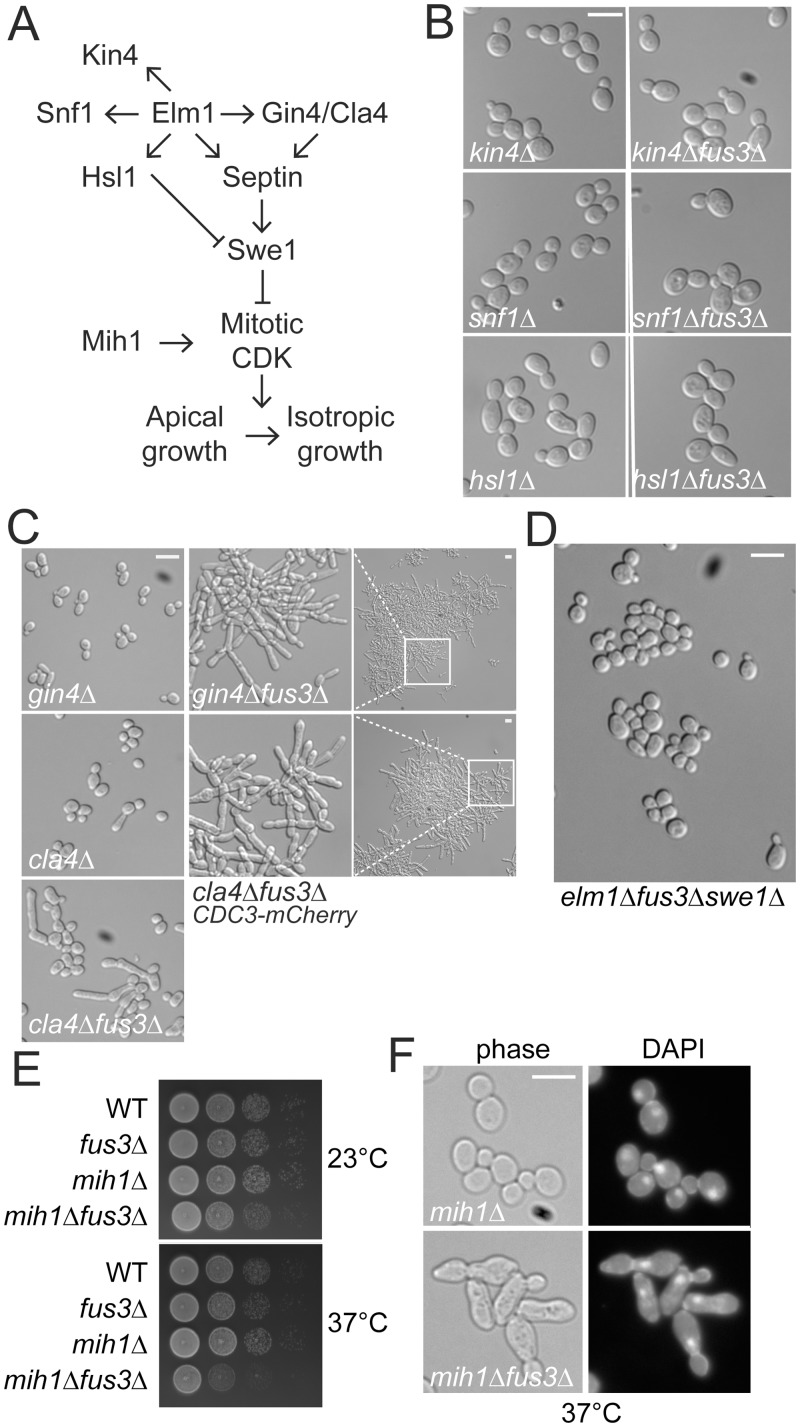

The bud-neck protein kinase Elm1p has multiple substrates that regulate distinct cellular functions (Fig 4A). To determine which functions are associated with sadF pseudohyphal growth, we examined strains carrying mutations in known Elm1p substrates. Kin4p is a component of the spindle-position checkpoint [25]. Elm1p is also an upstream kinase for Snf1p, the yeast AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [26]. Finally, Elm1p functions in a morphogenesis checkpoint pathway by phosphorylating Hsl1p, which coordinates bud growth and the G2/M transition by recruiting the Cdk-inhibitory kinase Swe1p to the bud neck for degradation [27]. Although deletions in each of these genes caused slight changes in the average axial ratio, in no case did the combination with fus3Δ lead to a significant increase in bud elongation (Fig 4B). Moreover, fus3Δ had no significant effect on the growth rate of kin4Δ, snf1Δ or hsl1Δ.

Fig 4. Genetic interaction of fus3Δ with septin associated genes.

All of strains were BY474-derivative haploids and grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C unless stated otherwise. (A) Schematic representation of Elm1p substrates and a morphogenesis checkpoint. For details, see Introduction. (B-D) Indicated strains (MY8092, 13826, 13827, 13829, 13830, 13832, 13833, 12156, 12871, 12886, 12941, 12944, 12990, 13125) was photographed. (E) Indicated cells (MY8092, 12886, 12960 and 12961) were serially diluted on YPD and incubated at either 23°C for 2 days or 37°C for 1 day. (F) MY12960 and 12961 cells grown to exponential phase at 23°C were transferred to 37°C for 12 hr. Cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with DAPI. (B-D, and F) Bar, 10 μm.

Elm1p contributes to proper formation of the septin cytoskeleton redundantly and/or partially through the protein kinases Gin4p and Cla4p (Fig 4A). To determine if disruption of septin organization is generally associated with pseudohyphal growth, we deleted FUS3 in gin4Δ and cla4Δ strains. Each mutant displayed a slightly elongated cell phenotype, compared to WT (Fig 4C; gin4Δ, 1.46±0.29, n = 164; cla4Δ, 1.32±0.30, n = 139; WT, 1.22 ±0.15, n = 112). However a significant number of gin4Δ cells were hyper-elongated by loss of Fus3p (3.13±0.99, n = 118; Fig 4C) and formed large aggregates of cells that rapidly settled out of solution (S1A Fig). Like elm1Δ, the fus3Δ mutation caused enhanced agar penetration of the gin4 mutant (S1B Fig). Similar results were observed with cla4Δ, but the combined effects with fus3Δ on polarized cell growth (1.91±1.11, n = 225), clumping and invasiveness were not as pronounced as for the gin4Δ mutants (Fig 4C and S1 Fig). However when the septin Cdc3p was tagged with mCherry, the cla4Δ fus3Δ cells displayed dramatic increases in cell elongation, cell-cell adhesion, and invasiveness (Fig 4C and S1 Fig). Although carboxy-terminally tagged Cdc3p-mCherry is thought to be fully functional, we observed slightly elongated buds, suggesting that it causes a slight septin defect. Taken together, the phenotypes of the elm1Δ fus3Δ, gin4Δ fus3Δ, and cla4Δ fus3Δ mutants suggest that mitotic septin defects are responsible for induction of pseudohyphal growth.

To further establish the relationship between Fus3p and septin perturbation in pseudohyphal growth, we examined the effect of fus3Δ on septin mutants. Four mutations (cdc3-3, cdc10Δ, cdc12-6, and shs1Δ) caused strong synthetic growth defects in combination with fus3Δ (S2A Fig). Two of the double mutants, cdc3-3 fus3Δ and cdc12-6 fus3Δ, displayed more severe morphologies with extremely elongated buds at the intermediate temperature of 30°C (S2B Fig). Taken together, these observations demonstrate that the loss of Fus3p exacerbates the effects of septin perturbation on cell morphology.

Perturbations of septin assembly lead to stabilization of Swe1p and a cell cycle delay at the G2/M transition, while buds undergo constitutive polarized growth [16]. A role for Swe1p in sadF pseudohyphal growth was demonstrated by finding that the swe1Δ completely suppressed the elongated cell morphology of elm1Δ fus3Δ cells (Fig 4D). The greatly enhanced polarization of elm1Δ fus3Δ, relative to elm1Δ, suggests that Swe1p may be further stabilized by loss of Fus3p. Mih1p promotes entry into mitosis by dephosphorylating the Swe1p-catalyzed inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1p [28]. If the loss of Fus3p affects the stability of Swe1p, then the fus3Δ mih1Δ double mutant should also show increased polarized bud growth and G2/M delay, relative to mih1Δ. Consistent with this hypothesis, fus3Δ caused increased bud elongation in mih1Δ and the double mutant exhibited defects in cell growth. These effects were more severe at elevated temperature (37°C), where most of cells were arrested with a single nucleus at the bud neck, indicative of G2 arrest (Fig 4E and 4F). However, because the fus3Δ mih1Δ mutant does not form chains of elongated cells, the effect of elm1Δ fus3Δ must entail more than Swe1p stabilization.

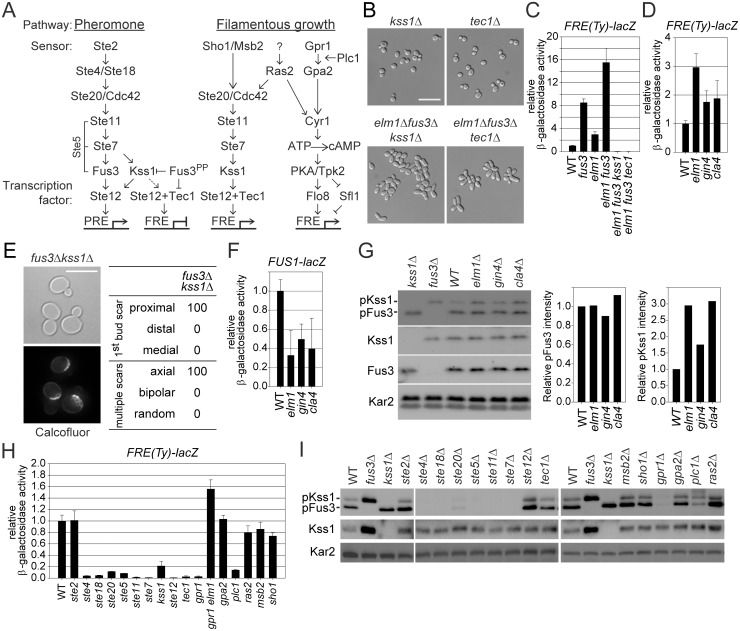

Activation of Kss1p MAP kinase signaling by septin defects

Pheromone-activated Fus3p blocks classical pseudohyphal growth by down-regulating Kss1p and Tec1p (Fig 5A; [29]). Because deletion of either KSS1 or TEC1 also eliminated the sadF pseudohyphal phenotype of elm1Δ fus3Δ (Fig 5B), we monitored the expression of a Tec1p-dependent filamentation response element (FRE). Expression of a FRE(Ty)-lacZ reporter was synergistically elevated 15 fold in elm1Δ fus3Δ relative to WT (8-fold in fus3Δ, and 3-fold in elm1Δ), which was obliterated by either kss1 or tec1 mutation (Fig 5C). FRE-lacZ expression was also elevated in the other septin assembly mutants, gin4Δ and cla4Δ, although less than in elm1Δ (Fig 5D). These data show that septin disruption upregulates Kss1p-dependent signaling, contributing to sadF pseudohyphal growth. Moreover, kss1Δ restored the normal axial budding pattern to a fus3Δ mutant (Figs 2 and 5E), suggesting that Kss1p signaling regulates the normal haploid budding pattern.

Fig 5. Upregulation of Kss1p-dependent signaling by fus3Δ mutation and septin assembly defects.

All of strains were BY474-derivative haploids and grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C unless stated otherwise. (A) Schematic representation of pheromone and filamentous growth pathway. For details, see the Introduction. (B) MY13049, 13122, 13144 and 13281 were photographed. (C and D) Indicated strains (MY8092, 12156, 12158, 12886, 12941, 12948, 13122, and 13281) harboring FRE(Ty)-lacZ (MR6857) were used. (E) The budding pattern of fus3Δ kss1Δ (MY13289) was analyzed as described in Fig 2B–2D. (F and G) MY8092, 12156, 12941 and 12948 strains were used. (F) Strains carry FUS1-lacZ (MR0727). (G) Intensities of phosphorylated Fus3p and Kss1p were normalized to total Fus3p and Kss1p and expressed relative to WT. (H) Indicated strains (MY8092, 13049, 13144, 13484, 13523, 13525, 14319, 14320, 14321, 14322, 14323, 14324, 14325, 14326, 14327, 14328, 14329 and 14330) harboring FRE(Ty)-lacZ (MR6857) were used. (I) Indicated strains (MY8092, 12886, 13049, 13144, 13523, 13525, 14319, 14320, 14321, 14322, 14323, 14324, 14325, 14326, 14327, 14328, 14329 and 14330) were used. (C, D, F, and H) Cells were grown to exponential phase in liquid SC containing 2% glucose. The activity of β-galactosidase was determined as described in Materials and Methods and expressed relative to wild type. Data are mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. (D and H) WT are identical to (C). (G and I) Active Fus3p and Kss1p were shown by phospho-p42/44 MAPK antibody. Total Fus3p, Kss1p and Kar2p were detected with anti-Fus3p, -Kss1p and -Kar2p respectively. (B and E) Bar, 10 μm.

How could Kss1p-dependent signaling be activated by septin assembly defects? Disruptions of mitotic septin organization and function could stimulate pheromone signaling, leading to increased activation of Kss1p in the absence of Fus3p inhibition. Expression of the mating-specific FUS1-lacZ reporter was activated >100-fold by pheromone. In contrast, the basal expression was reduced 2–3 fold in the elm1, gin4, or cla4 mutants (Fig 5F). Because there is a basal level of Kss1p-dependent signaling, septin defects might reduce the kinase activity and/or level of Fus3p, resulting in the upregulation of Kss1p signaling. However, neither the protein level nor the phosphorylation of Fus3p was significantly affected by elm1Δ, gin4Δ, or cla4Δ (Fig 5G). In contrast, the level of phosphorylated Kss1p was significantly elevated in elm1Δ, gin4Δ, and cla4Δ cells. Taken together, we conclude that septin assembly defects trigger signaling through Kss1p, independent of pheromone signaling and Fus3p.

To identify upstream regulators of the constitutive activation of Kss1p, we screened candidate deletion mutations in BY4741 for their effects on FRE-lacZ expression during vegetative growth. Basal FRE-driven expression was greatly reduced in strains lacking elements shared by both the pheromone response and pseudohyphal pathways, including ste20, ste11, ste7 and ste12 (Fig 5A and 5H). Remarkably, FRE-driven expression was also abolished by loss of components specific to the pheromone response, including Ste4p (Gβ), Ste18p (Gγ), and Ste5p (scaffold), but not by loss of the pheromone receptor, Ste2p. Ras2p and the plasma membrane-linked receptors Msb2p and Sho1p have been implicated in the activation of the fMAPK cascade during filamentous growth (Fig 5A). However, they are not required for basal signaling; null mutants showed ~80% WT expression (Fig 5H). Gpr1p (plasma membrane G-protein coupled receptor), Gpa2p (Gα), and Plc1p (phospholipase C) trigger filamentous growth by a pathway that is independent of fMAPK signaling (Fig 5A). FRE-driven expression was markedly abolished in gpr1Δ and plc1Δ, while gpa2Δ had no effect (Fig 5H).

Consistently, levels of phosphorylated Kss1p and Fus3p were almost abolished in cells carrying mutations in any genes of the pheromone pathway, with the exception of STE2 (Fig 5I). Similarly, gpr1Δ and plc1Δ, but not mutations in other upstream regulators of filamentous growth also caused decreased phosphorylation (Fig 5I). Our data indicate that basal signaling through Kss1p in the S288C derived BY4741 strain is mediated by Gpr1p and the pheromone response pathway downstream of the pheromone receptor. Importantly, deletion of ELM1 greatly elevated FRE-lacZ expression in gpr1Δ (Fig 5H), indicating that septin defects activate the pathway independent of Gpr1p.

We next asked if Fus3p’s kinase activity is required for regulating sadF pseudohyphal growth. The kinase-defective fus3K42R could partially suppress cell elongation and FRE-driven expression (S3 Fig). We conclude that Fus3p down-regulation of sadF pseudohyphal growth is only partially dependent on its kinase activity.

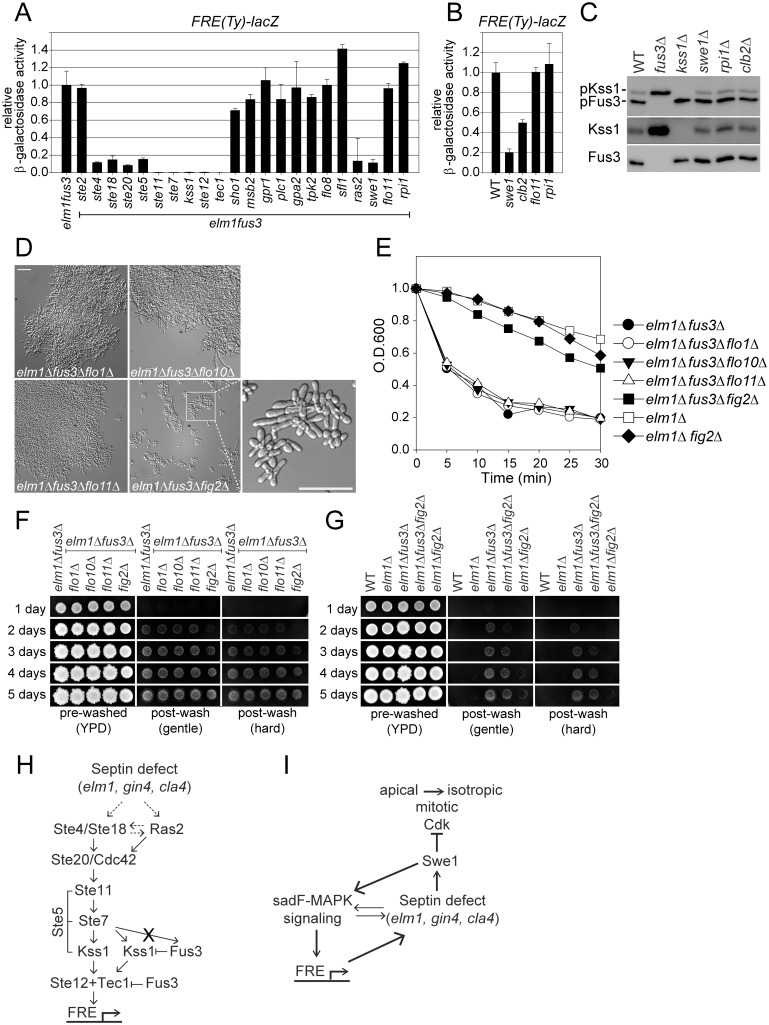

The signaling pathway of sadF pseudohyphal growth

To identify the signaling pathway for sadF pseudohyphal growth, we screened the mutants for their effects on the induced level of FRE-lacZ in the elm1Δ fus3Δ mutant. Note that the elm1Δ fus3Δ induced level of FRE-lacZ expression is roughly 15-fold higher than the basal level (Fig 5C). As shown in Fig 6A, all the genes required for the basal level of FRE-driven expression are also essential for elm1Δ fus3Δ stimulated expression, with the exception of GPR1 and PLC1. Deletion of either gene had no effect, indicating that Gpr1 and Plc1are not required for sadF pseudohyphal growth. As found for basal expression, the msb2 and sho1 mutants were essentially wild type (~70–80%) (Fig 6A). In contrast, deletion of RAS2 largely abolished the induced level of FRE-driven expression, suggesting that defects in mitotic septin organization/function might stimulate sadF pseudohyphal signaling via Ras2p. Accordingly we investigated other components of the cAMP/PKA pathway, although BY4741 like other S288C strains carries a mutation in FLO8. As expected, sfl1Δ, tpk2Δ and flo8Δ did not cause any significant decrease in FRE-driven expression (Fig 6A). All triple mutants with significantly-reduced FRE-lacZ expression also failed to display the sadF pseudohyphal phenotype, consistent with the critical role for induced levels of Kss1p activation and Tec1p dependent transcription.

Fig 6. Identification of sadF pseudohyphal signaling pathway.

All of strains were BY474-derivative haploids and grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C unless stated otherwise. (A and B) Indicated strains (MY8092, 12948, 13122, 13125, 13145, 13281, 13313, 13315, 13317, 13319, 13378, 13380, 13382, 13384, 13413, 13417, 13500, 13502, 13504, 13506, 13508, 13531, 13582, 14331, 14332, 14333, 14334 and 14335) harboring FRE(Ty)-lacZ (MR6857) were used. β-galactosidase activity was determined as described in Fig 5C. Data are expressed relative to (A) elm1Δ fus3Δ or (B) WT. Data are mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. Note that (A) elm1Δ fus3Δ, elm1Δ fus3Δ kss1Δ, elm1Δ fus3Δ tec1Δ and (B) WT are identical to Fig 5C. (C) MY8092, 12886, 13144 and 13145 strains were used. Each protein was detected as described as Fig 5G. (D-G) Indicated strains (MY12158, 12948, 13413, 13901, 13903, 13907 and 14336) were used. (D) Bar, 30μm. (E) Flocculation assay was performed as described in Fig 1F. Data are representative of three independent experiments and expressed relative to WT. Note that elm1Δ and elm1Δ fus3Δare identical to Fig 1F. (F and G) Plate washing assay was performed as described in Fig 1G. (H and I) A model for sadF pseudohyphal signaling pathway. See the Discussion for details.

Given that swe1Δ suppresses sadF pseudohyphal growth, we examined its effect on FRE-driven transcription. Surprisingly, loss of Swe1p also strongly suppressed FRE-driven transcription in elm1Δ fus3Δ (Fig 6A). The swe1Δ also reduced basal expression of FRE-lacZ (Fig 6B), but it had little effect on basal Kss1p phosphorylation (Fig 6C), suggesting that Swe1p acts downstream of Kss1p to regulate FRE-driven expression. Because Swe1p negatively regulates the mitotic Cdk, the reduction in FRE-driven expression by deletion of SWE1 might be due to the increased Cdk activity. If so, then FRE-driven expression should be upregulated in a strain lacking Clb2p, the major mitotic cyclin. However, clb2Δ did not stimulate FRE-reporter expression; instead, cells exhibited a 2-fold reduction (Fig 6C). These results suggest that Swe1p’s function in sadF pseudohyphal signaling is not solely dependent on reduction of mitotic Cdk activity.

The classic forms of filamentous growth require Flo11p, a cell surface flocculin, to promote filamentation and agar invasion. We therefore examined whether sadF pseudohyphae are Flo11p-dependent. Deletion of FLO11 had no effect on sadF pseudohyphal signaling (Fig 6A), basal FRE-driven expression (Fig 6B), filamentation (Fig 6D), aggregation (Fig 6E) or agar invasion of elm1Δ fus3Δ cells (Fig 6F). Recently it was shown that S288C strains bypass fMAPK signaling for Flo11p induction; instead, Rpi1p regulates transcription of FLO11 [30]. The rpi1Δ had no effect on the sadF pseudohyphal phenotype or signaling (Fig 6A and 6B) again showing that sadF pseudohyphal growth is independent of Flo11p and the cAMP/PKA pathway.

Budding yeast has several cell wall proteins related to the adhesins of pathogenic fungi including Flo1p, Flo10p, Flo11p, and Fig2p. Flo1p and Flo10p promote cell-cell adhesion to form multicellular clumps, leading to flocculation [31]. Fig2p is induced during mating and implicated in cell-cell adherence for cell fusion [32]. As shown in Fig 6D–6F, flo1Δ and flo10Δ had no effect on the morphology, clumping or invasiveness of sadF pseudohyphal cells. In contrast, fig2Δ partially suppressed sadF pseudohyphal growth, showing reduced cell clump size, reduced clumping, and reduced agar invasion of the elm1Δ fus3Δ strain (Fig 6D–6G). Thus sadF pseudohyphal growth also differs from the classical forms of filamentation in requiring a different adhesin to promote multicellular growth.

Discussion

In this paper we report the discovery of a stable constitutive pseudohyphal growth state for the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The constitutive pseudohyphal growth, referred to as sadF growth, is triggered by two regulatory inputs: perturbation in the assembly of the septin ring required for cytokinesis and relief of the negative regulation of Kss1p by the mating pathway MAP kinase, Fus3p. As for classical filamentous growth, sadF growth is characterized by hyperpolarized cell growth, a unipolar budding pattern and increased cell adhesion, leading to growth as large clumps of branched filaments. Although sadF pseudohyphal growth shares some characteristics with classical diploid pseudohyphal growth, it differs in significant ways, including the conditions in which it occurs (liquid rich media versus solid starvation media), the overall genetic requirements (haploid S288C background versus diploid ∑), the regulatory pathway (dependent on Ste5p, but independent of the cAMP/PKA pathway and Flo11p), and the degree of hyperpolarized growth. Besides nitrogen starvation, various environmental stimuli such as alcohol and slowed DNA synthesis have also been revealed to promote filamentation [33, 34]; short-chain alcohols were able to stimulate filamentous growth even in liquid media with properties similar to classical pseudohyphal growth. However, these filamentous growths were not induced in strains of the S288C lineage [33, 34].

The sadF pseudohyphal cells achieve a degree of polarized growth that is significantly more extreme than that previously reported for diploid filamentous growth (mean axial ratio of 4.3, versus 3.4; [2]). However, the distribution of sadF pseudohyphal cell lengths was highly variable, with some cells superficially resembling the hyphae of true filamentous fungi. Like filamentous fungi, sadF pseudohyphal yeast contain a Spitzenkörper-like structure at the tips of the growing cells (Fig 3D). Comprised of secretory and endocytic vesicles, the Spitzenkörper is thought to be a staging area for secreted material that will form the new cell surface. During budding, S. cerevisiae growth is isotropic over the bud surface, with no evidence of a Spitzenkörper. Although Spitzenkörper have not been reported in S. cerevisiae pseudohyphal growth, in the related human pathogen, Candida albicans, which can grow both as true hyphae and as pseudohyphae, Spitzenkörper are observed only in true hyphae [35]. Interestingly, a Spitzenkörper-like structure is seen in budding yeast during the response to pheromone ([36], Bagamery and Rose, submitted), indicating that budding yeast have the machinery for Spitzenkörper formation. Moreover, a Spitzenkörper-like structure is observed in budding yeast, early in the cell cycle, prior to the “apical to isotropic” switch (Bagamery and Rose, submitted). Thus it seems likely that the sadF hyper-polarized growth reflects the maintenance of a growth pattern that is normally restricted to mating and/or the early phases of the cell cycle.

Septin assembly defects appear to induce pseudohyphal growth through two different signaling pathways (Fig 6H and 6I). First, septin defects activate a MAP kinase pathway (sadF-MAPK) comprising most components of the pheromone response pathway, including ones that are not shared with the pseudo-hyphal signaling pathway (Ste4p/Ste18p and Ste5p). It is not known how the sadF-MAPK signaling pathway is activated by septin defects, although we note the presence of increased levels of Ste5-GFP at cortical puncta and the bud neck in strains undergoing sadF pseudohyphal growth (S4 Fig). Septin assembly must be normally monitored by the sadF-MAPK pathway; mutations affecting septins caused up to 3 fold higher Kss1p phosphorylation and Tec1p-dependent FRE-reporter expression. Under normal conditions, the expression of the filamentation response genes is ameliorated by Fus3p. In the absence of Fus3p, filamentation response gene expression is greatly enhanced; the expression of which leads to further suppression of septin assembly and the pronounced changes in cell morphology characteristic of pseudohyphal growth.

Septin assembly defects is also monitored by Swe1p, whose activation leads to cell cycle arrest prior to the switch from apical to isotropic growth [20]. A role for Swe1p-dependent cell-cycle arrest in sadF pseudohyphal growth is supported by the finding that loss of Mih1p (which antagonizes Swe1p activity) leads to cell elongation in a fus3Δ mutant (Fig 4F). At the same time, Swe1p is also required for high level sadF-MAPK signaling. Surprisingly, Swe1p does not appear to be required upstream in the signaling pathway; Swe1p is not required for Kss1p phosphorylation. To explain this finding, we propose that activation of the Swe1p-dependent septin assembly checkpoint blocks cell cycle progression at the precise stage during which septin assembly is actively being monitored by the sadF-MAPK pathway. Because high-level expression of the filamentation response genes appears to exacerbate septin assembly defects (S2 Fig), cells become locked in a state in which both Swe1p and sadF-MAPK signaling remain high, essentially creating a positive feedback loop (Fig 6H). Because cells remain blocked in the cell cycle prior to the switch from apical to isotropic growth, they continue to grow in a highly polarized, hyphal-like fashion. The cell cycle block is not permanent as cells eventually succeed at completing cytokinesis, albeit after most have grown to a length that is at least 4 to 5 times longer than wild-type.

We presume that other cellular functions associated with the filamentation response genes contribute to the unique cell morphology of sadF pseudohyphal growth. For example, loss of Fus3p is sufficient to switch about 30% of cells from the haploid axial budding pattern to the bipolar budding pattern (Fig 2), rising to 90% when coupled to elm1Δ. Similarly, the Fig2p adhesin is required for the full level of cell adhesion. Although FIG2 has not been reported to be a filamentation response gene, overexpression causes increased filamentation and the promoter region binds Phd1p, a transcription factor that enhances filamentous growth. Moreover, in Ashbya gossypii FIG2 expression was abolished in a tec1 mutant [37]. Thus the sadF pseudohyphal growth state can be viewed as the product of synergism between the set of genes which regulate aspects of cell morphology and genes which regulate progression through the cell cycle.

Aside from notable differences in the regulatory mechanism, sadF pseudohyphal growth is remarkable because it is a stable growth state that is independent of the external environmental cues that trigger classical pseudohyphal growth. The various growth states of budding yeast can be thought of as being dominated by the activity of specific master regulatory protein kinases. For example, mitosis is dominated by the activity of the CDK, Cdc28p. Mating is dominated by the activity of the MAPK, Fus3p. Meiosis is dominated by Ime1p. Each growth state activates mechanisms to suppress the activity of alternate growth phase kinases. For example, phosphorylation of Ste5p by Cdc28p blocks activation of Fus3p prior to G2 [38]. During mating, activation of Far1p by Fus3p blocks activation of Cdc28p to prevent reentry into mitosis. Similarly, sadF pseudohyphal growth can be thought of as being dominated by Swe1p and Kss1p, which synergistically activate genes responsible for the alternate growth state and block Cdc28p-dependent mitotic progression.

Much recent interest has focused on the mechanism by which unicellular organisms transitioned to multicellular patterns of growth. Using different selection schemes two different laboratory groups have evolved yeast strains into forms that show a striking degree of multicellularity [39,40]. In both cases cells showed dramatic increases in the level of adhesion, although neither showed significant changes in cell morphology. The relative ease of the transition for budding yeast has suggested that the evolution of multicellularity might be generally easy for unicellular eukaryotes under proper selective pressure. Our results show that loss of function mutations in just two genes can also induce a high degree of multicellularity in budding yeast. Thus this organism may already contain the genomic complexity required for robust multicellular growth.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains, plasmids, growth conditions and general methods

All yeast culture and genetic techniques were performed as described by [41]. Yeast strains and plasmids are listed in S1 Table. All yeast strains are haploid congenic to the S288C genetic background and were grown in liquid culture of rich YPD (yeast extract/peptone/dextrose) media unless indicated otherwise. The gene disruption and GFP tagging of HTB1 were performed by PCR-based methods [42]. To determine cell-cell adhesion quantitatively, a flocculation assay was performed as described previously [43]. Briefly, exponentially growing cells in liquid YPD media were thoroughly mixed and the absorbance (A600) was determined immediately (t = 0) with a spectrophotometer. Optical density was read at 5 min intervals for 30 min without agitation and normalized by those of t = 0. β-galactosidase assays were performed with extracts from exponentially growing cells in synthetic minimal medium containing 2% glucose as described previously [29].

Protein analysis

Proteins were prepared by TCA precipitation as described previously [41] and probed with polyclonal anti-Kss1p (Santa Cruz), polyclonal anti-Fus3p (Santa Cruz), monoclonal anti-phosphor-p44/42 MAPK (Cell signaling), and polyclonal Kar2p (Rose Lab, Princeton University). Band intensity was quantified using G:BOX imaging system (Syngene).

Microscopy and cell imaging

Images for colony morphology were acquired with G:BOX imaging system (Syngene). Florescence microscopy was performed essentially as described previously [44]. Images were acquired on a DeltaVision Microscopy System (Applied Precision, LLC) using an inverted microscope (TE200; Nikon), a charge-coupled device camera (CoolSNAP HQ; Roper Scientific) and either a 40× objective with a 0.75 NA or a 20× with a 0.50 NA (Nikon). Figures were prepared for publication using Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator. No further manipulations other than adjustments in brightness and contrast were made. To determine DNA contents, cells were grown to exponential phase, fixed with 70% ethanol, and treated with RNAase. The cells were then stained with propidium iodide overnight at 4°C and fluorescent intensity was quantified with CellProfiler image analysis software [45]. For time-lapse experiments, cells were grown to early exponential phase in liquid YPD medium and were placed on YPD agarose pads. 10 z sections spaced 1 μm apart without binning were acquired every 2 min. All images were projected and processed with the softWoRx program (Applied Precision, LLC).

Supporting Information

All of strains were BY474-derivative haploids and grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C. MY8091, 12156, 12871, 12886, 12941, 12944, and 12990 strains were used. (A) Flocculation assay was performed as described in Fig 1F. Data are representative of three independent experiments and expressed relative to wild type. Note that wild type and fus3Δ are identical to Fig 1F. (B) Plate washing assay was performed as described in Fig 1G.

(TIF)

All of strains were BY474-derivative haploids. MY8092, 12886, 12969, 12970, 14050, 14054, 14056, 14058, 14132, 14134, 14136 and 14139 strains were used. The temperature-sensitive cdc3-3, cdc11-6 and cdc12-6 mutants were constructed in BY4741. (A) Cells were serially diluted on YPD and incubated at 23°C for 2 days, 30°C for 1 day, or 37°C for 1 day. (B) Cells grown to exponential phase in YPD liquid at 23°C were transferred to 30°C for 12 hr. Bar, 10 μm. To further establish the relationship between Fus3p and septin perturbation in pseudohyphal growth, we examined the effect of fus3Δ on the growth and morphology of septin mutants. Neither Cdc10p nor Shs1p are essential in BY4741 and their absence resulted only in a slightly elongated bud phenotype that was not sensitive to elevated temperature. In contrast, Cdc3p, Cdc11p and Cdc12p are essential proteins and temperature-sensitive mutants displayed elongated cell morphology that became significantly more severe at elevated temperatures, becoming inviable at 37°C. The different septin mutations exhibited a variety of interactions with fus3Δ. Four of the five mutations (cdc3-3, cdc10Δ, cdc12-6, and shs1Δ) showed strong synthetic growth defects with fus3Δ, such that the growth of the double mutants was greatly reduced relative to either single mutant at otherwise permissive temperatures (S2A Fig). Two of the double mutants, cdc3-3 fus3Δ and cdc12-6 fus3Δ, displayed more severe morphologies with extremely elongated buds at the intermediate temperature of 30°C (S2B Fig). Although shs1Δ fus3Δ double mutant did not show elongated buds, the cells aggregated into clumps that were not dispersed by sonication (S2B Fig). In contrast to the other septin mutants, fus3Δ did not cause an obvious synthetic growth defect in combination with cdc11-6 (S2A Fig) and the effect of fus3Δ on cdc11-6 morphology was less severe compared to cdc3-3 and cdc12-6 (S2B Fig). Taken together, these interactions suggest that the various septin mutations perturb septation in a variety of ways leading to differential genetic interactions with fus3Δ.

(TIF)

elm1Δ fus3Δ (MY12948) harboring kinase-defective pCEN-fus3K42R (MR6763) were grown in liquid SC contacting 2% glucose and photographed (left). elm1Δfus3Δ (MY12948) harboring either pCEN-FUS3 (MR5048) or pCEN-fus3K42R (MR6763) were transformed with FRE(Ty)-lacZ (MR6857) and β-galactosidase activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Bar, 10 μm.

(TIF)

Indicated cells (MY13378, 13394 and 14322) harboring pCEN-STE5-3GFP (pMR6725) were grown to exponential phase in liquid SC media containing glucose at 30°C. GFP fluorescence was observed in living cells. Bar, 10 μm.

(TIF)

Unless indicated otherwise, all strains were constructed in this study.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeremy Thorner for providing yeast strains and plasmids. The authors thank May Husseini for excellent help with media and materials. We acknowledge members of the laboratory for helpful discussion on this work.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant: #GM037739. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Lo HJ, Kohler JR, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, et al. (1997) Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90: 939–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gimeno CJ, Ljungdahl PO, Styles CA, Fink GR (1992) Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68: 1077–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kron SJ, Styles CA, Fink GR (1994) Symmetric cell division in pseudohyphae of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Biol Cell 5: 1003–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roberts RL, Fink GR (1994) Elements of a single MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediate two developmental programs in the same cell type: mating and invasive growth. Genes Dev 8: 2974–2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cullen PJ, Sprague GF Jr. (2012) The regulation of filamentous growth in yeast. Genetics 190: 23–49. 10.1534/genetics.111.127456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sabbagh W Jr., Flatauer LJ, Bardwell AJ, Bardwell L (2001) Specificity of MAP kinase signaling in yeast differentiation involves transient versus sustained MAPK activation. Mol Cell 8: 683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chou S, Huang L, Liu H (2004) Fus3-regulated Tec1 degradation through SCFCdc4 determines MAPK signaling specificity during mating in yeast. Cell 119: 981–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Good M, Tang G, Singleton J, Remenyi A, Lim WA (2009) The Ste5 scaffold directs mating signaling by catalytically unlocking the Fus3 MAP kinase for activation. Cell 136: 1085–1097. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toda T, Uno I, Ishikawa T, Powers S, Kataoka T, et al. (1985) In yeast, RAS proteins are controlling elements of adenylate cyclase. Cell 40: 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu H, Styles CA, Fink GR (1996) Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C has a mutation in FLO8, a gene required for filamentous growth. Genetics 144: 967–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Longtine MS, Bi E (2003) Regulation of septin organization and function in yeast. Trends Cell Biol 13: 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McMurray MA, Thorner J (2009) Septins: molecular partitioning and the generation of cellular asymmetry. Cell Div 4: 18 10.1186/1747-1028-4-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mortensen EM, McDonald H, Yates J 3rd, Kellogg DR (2002) Cell cycle-dependent assembly of a Gin4-septin complex. Mol Biol Cell 13: 2091–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Versele M, Thorner J (2004) Septin collar formation in budding yeast requires GTP binding and direct phosphorylation by the PAK, Cla4. J Cell Biol 164: 701–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tjandra H, Compton J, Kellogg D (1998) Control of mitotic events by the Cdc42 GTPase, the Clb2 cyclin and a member of the PAK kinase family. Curr Biol 8: 991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Longtine MS, Theesfeld CL, McMillan JN, Weaver E, Pringle JR, et al. (2000) Septin-dependent assembly of a cell cycle-regulatory module in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Cell Biol 20: 4049–4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asano S, Park JE, Yu LR, Zhou M, Sakchaisri K, et al. (2006) Direct phosphorylation and activation of a Nim1-related kinase Gin4 by Elm1 in budding yeast. J Biol Chem 281: 27090–27098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sreenivasan A, Kellogg D (1999) The elm1 kinase functions in a mitotic signaling network in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol 19: 7983–7994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bouquin N, Barral Y, Courbeyrette R, Blondel M, Snyder M, et al. (2000) Regulation of cytokinesis by the Elm1 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Cell Sci 113 (Pt 8): 1435–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lew DJ (2003) The morphogenesis checkpoint: how yeast cells watch their figures. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elion EA, Grisafi PL, Fink GR (1990) FUS3 encodes a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase required for the transition from mitosis into conjugation. Cell 60: 649–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chant J, Pringle JR (1995) Patterns of bud-site selection in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Cell Biol 129: 751–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Virag A, Harris SD (2006) The Spitzenkorper: a molecular perspective. Mycol Res 110: 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gladfelter AS (2006) Control of filamentous fungal cell shape by septins and formins. Nat Rev Microbiol 4: 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moore JK, Chudalayandi P, Heil-Chapdelaine RA, Cooper JA (2010) The spindle position checkpoint is coordinated by the Elm1 kinase. J Cell Biol 191: 493–503. 10.1083/jcb.201006092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sutherland CM, Hawley SA, McCartney RR, Leech A, Stark MJ, et al. (2003) Elm1p is one of three upstream kinases for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF1 complex. Curr Biol 13: 1299–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Szkotnicki L, Crutchley JM, Zyla TR, Bardes ES, Lew DJ (2008) The checkpoint kinase Hsl1p is activated by Elm1p-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell 19: 4675–4686. 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Russell P, Moreno S, Reed SI (1989) Conservation of mitotic controls in fission and budding yeasts. Cell 57: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Madhani HD, Styles CA, Fink GR (1997) MAP kinases with distinct inhibitory functions impart signaling specificity during yeast differentiation. Cell 91: 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chin BL, Ryan O, Lewitter F, Boone C, Fink GR (2012) Genetic variation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: circuit diversification in a signal transduction network. Genetics 192: 1523–1532. 10.1534/genetics.112.145573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guo B, Styles CA, Feng Q, Fink GR (2000) A Saccharomyces gene family involved in invasive growth, cell-cell adhesion, and mating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 12158–12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erdman S, Lin L, Malczynski M, Snyder M (1998) Pheromone-regulated genes required for yeast mating differentiation. J Cell Biol 140: 461–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lorenz MC, Cutler NS, and Heitman J (2000) Characterization of alcohol-induced filamentous growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Biol Cell 11: 183–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang YW, Kang CM (2003) Induction of S. cerevisiae filamentous differentiation by slowed DNA synthesis involves Mec1, Rad53 and Swe1 checkpoint proteins. Mol Biol Cell 14: 5116–5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crampin H, Finley K, Gerami-Nejad M, Court H, Gale C, et al. (2005) Candida albicans hyphae have a Spitzenkorper that is distinct from the polarisome found in yeast and pseudohyphae. J Cell Sci 118: 2935–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chapa YLB, Lee S, Regan H, Sudbery P (2011) The mating projections of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans show key characteristics of hyphal growth. Fungal biology 115: 547–556. 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grunler A, Walther A, Lammel J, Wendland J (2010) Analysis of flocculins in Ashbya gossypii reveals FIG2 regulation by TEC1. Fungal Genet Biol 47: 619–628. 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Strickfaden SC, Winters MJ, Ben-Ari G, Lamson RE, Tyers M, et al. (2007) A mechanism for cell-cycle regulation of MAP kinase signaling in a yeast differentiation pathway. Cell 128: 519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ratcliff WC, Denison RF, Borrello M, Travisano M (2012) Experimental evolution of multicellularity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 1595–1600. 10.1073/pnas.1115323109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koschwanez JH, Foster KR, Murray AW (2011) Sucrose utilization in budding yeast as a model for the origin of undifferentiated multicellularity. PLoS biology 9: e1001122 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim J, Rose MD (2012) A mechanism for the coordination of proliferation and differentiation by spatial regulation of Fus2p in budding yeast. Genes Dev 26: 1110–1121. 10.1101/gad.187260.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Longtine MS, McKenzie A 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, et al. (1998) Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen RE, Thorner J (2010) Systematic epistasis analysis of the contributions of protein kinase A- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent signaling to nutrient limitation-evoked responses in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics 185: 855–870. 10.1534/genetics.110.115808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ydenberg CA, Rose MD (2009) Antagonistic regulation of Fus2p nuclear localization by pheromone signaling and the cell cycle. J Cell Biol 184: 409–422. 10.1083/jcb.200809066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lamprecht MR, Sabatini DM, Carpenter AE (2007) CellProfiler: free, versatile software for automated biological image analysis. Biotechniques 42: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All of strains were BY474-derivative haploids and grown to exponential phase in liquid YPD at 30°C. MY8091, 12156, 12871, 12886, 12941, 12944, and 12990 strains were used. (A) Flocculation assay was performed as described in Fig 1F. Data are representative of three independent experiments and expressed relative to wild type. Note that wild type and fus3Δ are identical to Fig 1F. (B) Plate washing assay was performed as described in Fig 1G.

(TIF)

All of strains were BY474-derivative haploids. MY8092, 12886, 12969, 12970, 14050, 14054, 14056, 14058, 14132, 14134, 14136 and 14139 strains were used. The temperature-sensitive cdc3-3, cdc11-6 and cdc12-6 mutants were constructed in BY4741. (A) Cells were serially diluted on YPD and incubated at 23°C for 2 days, 30°C for 1 day, or 37°C for 1 day. (B) Cells grown to exponential phase in YPD liquid at 23°C were transferred to 30°C for 12 hr. Bar, 10 μm. To further establish the relationship between Fus3p and septin perturbation in pseudohyphal growth, we examined the effect of fus3Δ on the growth and morphology of septin mutants. Neither Cdc10p nor Shs1p are essential in BY4741 and their absence resulted only in a slightly elongated bud phenotype that was not sensitive to elevated temperature. In contrast, Cdc3p, Cdc11p and Cdc12p are essential proteins and temperature-sensitive mutants displayed elongated cell morphology that became significantly more severe at elevated temperatures, becoming inviable at 37°C. The different septin mutations exhibited a variety of interactions with fus3Δ. Four of the five mutations (cdc3-3, cdc10Δ, cdc12-6, and shs1Δ) showed strong synthetic growth defects with fus3Δ, such that the growth of the double mutants was greatly reduced relative to either single mutant at otherwise permissive temperatures (S2A Fig). Two of the double mutants, cdc3-3 fus3Δ and cdc12-6 fus3Δ, displayed more severe morphologies with extremely elongated buds at the intermediate temperature of 30°C (S2B Fig). Although shs1Δ fus3Δ double mutant did not show elongated buds, the cells aggregated into clumps that were not dispersed by sonication (S2B Fig). In contrast to the other septin mutants, fus3Δ did not cause an obvious synthetic growth defect in combination with cdc11-6 (S2A Fig) and the effect of fus3Δ on cdc11-6 morphology was less severe compared to cdc3-3 and cdc12-6 (S2B Fig). Taken together, these interactions suggest that the various septin mutations perturb septation in a variety of ways leading to differential genetic interactions with fus3Δ.

(TIF)

elm1Δ fus3Δ (MY12948) harboring kinase-defective pCEN-fus3K42R (MR6763) were grown in liquid SC contacting 2% glucose and photographed (left). elm1Δfus3Δ (MY12948) harboring either pCEN-FUS3 (MR5048) or pCEN-fus3K42R (MR6763) were transformed with FRE(Ty)-lacZ (MR6857) and β-galactosidase activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Bar, 10 μm.

(TIF)

Indicated cells (MY13378, 13394 and 14322) harboring pCEN-STE5-3GFP (pMR6725) were grown to exponential phase in liquid SC media containing glucose at 30°C. GFP fluorescence was observed in living cells. Bar, 10 μm.

(TIF)

Unless indicated otherwise, all strains were constructed in this study.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.