Abstract

Background A safe and easy anatomical landmark is proposed to identify the facial nerve in parotid surgery. The facial nerve forms the center point between the base of the styloid process and the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.

Objective To evaluate the consistency, accuracy, and safety of the landmark in identifying the facial nerve.

Methods The study was designed in three steps: a cadaver study, a radiologic study, and a prospective clinical study. Anatomy was initially studied in two cadavers. Then the images of 200 temporal styloid regions were studied for consistency of the presence of the styloid base. In the second part of the radiologic study, the distance between the styloid base and the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle was studied in 50 parotid regions. The clinical study involved 25 patients who underwent parotidectomy.

Results The styloid base was present in all the images studied. The mean distance between the styloid base and the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric was found to be 0.72 cm (range: 0.45–0.99 cm). The facial nerve could be identified consistently and safely in all patients.

Conclusion This trident landmark provided safe, accurate, and easy identification of the facial nerve using two fixed bony landmarks.

Keywords: facial nerve, parotidectomy, styloid process, digastric muscle, tragal pointer

Introduction

Identification of the facial nerve is the most crucial step in parotid surgery. Avoidance of an inadvertent injury to the facial nerve is of utmost importance because the resulting paralysis can severely affect facial expression, swallowing, speech, eye closure, and the social life of the patient. Hence the safe identification and dissection of the facial nerve is an important challenge in parotid surgery.

The importance of the facial nerve and controversies about how to identify it are exemplified by the multiple anatomical landmarks described to identify the facial nerve during parotidectomy.1 2 3 4 These include the tragal pointer, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, external auditory canal (EAC), tympanomastoid suture (TMS), transverse process of axis, angle of mandible, styloid process, and stylomastoid artery. A review of literature shows that the debate about the best landmark to identify the facial nerve in parotid surgery is far from over. The present study is also the result of the search for a safe, reliable, and easily identifiable landmark for the facial nerve.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in a tertiary head and neck institution. The first author used the method described here to identify the facial nerve during parotidectomy and temporal bone resection. This was conveyed and discussed with the other authors and prompted the study, which was designed in three steps: first as a cadaver study, followed by a radiologic study that consisted of two parts, and a prospective clinical study.

The anatomical landmark of the styloid base was defined as the proximal part of the temporal styloid process, developmentally the tympanohyal part, which is ensheathed by the vaginal process of the tympanic portion.5 The superior border of the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle from the digastric notch of the mastoid was the second landmark, and the main trunk of the facial nerve coming in between the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the base of the styloid process was the third landmark.

Cadaver Study

The dissection to demonstrate the method to identify the base of the styloid, the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric, and the relationship of the facial nerve to these structures was performed on two adult cadavers.

Radiologic Study

The radiologic study was done in two parts. The consistency of the styloid base in the computed tomography (CT) scans of 100 adult subjects, consisting of 200 temporal styloid regions, with no obvious congenital anomaly of the head and neck region who underwent imaging of head and neck for unrelated reasons, were randomly selected and studied. The length of the styloid process was categorized as the styloid base alone, < 1 cm length from the base, 1 to 2 cm length from the base, and > 2 cm length from the base. This was measured by a senior radiologist with a special interest in the head and neck.

The second part of the radiologic study was to find the average distance between the base of the styloid and the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, to give an idea regarding the area to be dissected to identify the facial nerve. This was done using three-dimensional (3D) reconstructed CT scans of 25 randomly selected subjects, bilaterally amounting to 50 parotid regions, with no congenital anomaly of the head and neck region, who underwent head and neck imaging for unrelated reasons. Osirix software was used for this analysis.

Clinical Study

The clinical study was done prospectively and included 25 parotidectomies with various surgeons involved in the study. These included 25 adult patients with parotid tumors of benign or malignant pathology operated on between July 2012 and January 2014. Once the landmarks were identified, a nerve stimulator was used to confirm the facial nerve.

Technique of Parotidectomy and Description of the Landmark

The initial steps of surgery are similar to a routine parotidectomy with a modified Blair incision along the preauricular skin crease that turns below the root of the ear lobule anteriorly in a horizontal neck crease, ∼ 5 cm below the angle of the mandible. A subplatysmal and sub-superficial musculoaponeurotic system flap is elevated to expose the parotid gland with the capsule. The greater auricular nerve is identified, and the posterior division is preserved if not contraindicated oncologically. Dissection is performed using a cold instrument or bipolar cautery vertically along the anterior surface of the tragal cartilage until the bony anterior wall of the EAC. From here the dissection is preferably done using a blunt instrument. Dissection is to be done vertically along the anterior surface of the bony EAC. The next bony structure, which is the only bony landmark present immediately deep to the bony EAC, is the base of the styloid, which can be easily identified. This forms the upper point of the tri-point landmark. Now the posterior belly of the digastric muscle is identified deep to the sternocleidomastoid and followed to its origin from the mastoid tip. The superior border of the origin of the posterior belly of digastric from the digastric notch of mastoid process forms the lower point of the landmark. The area in between these two points houses the facial nerve and was < 1 cm (0.5–0.9 cm) in all cases we studied. Care should be taken not to cause bleeding that may make visibility poor. The emergence of the facial nerve in between the two structures is similar to the central prong of a trident. Careful dissection in the direction of the central prong of the trident will help identify the facial nerve. Once the main trunk of the facial nerve is identified, the rest of the dissection is similar to a routine parotidectomy, tracing the divisions and further branches of the nerve.

Results

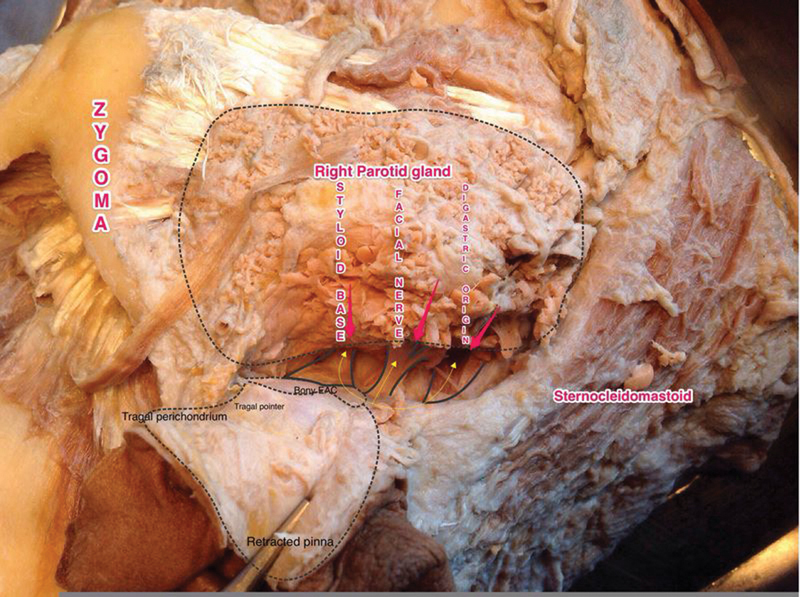

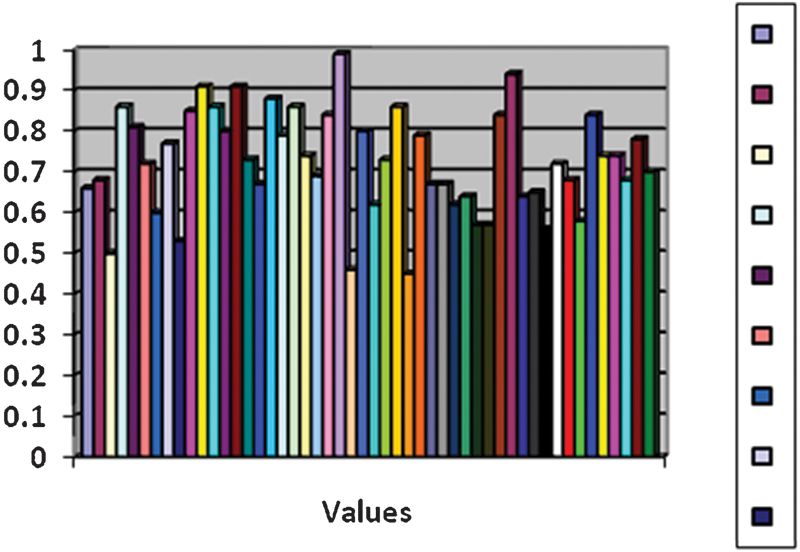

In the cadaver study, the landmarks could be identified successfully and convincingly. The safety of the method and ease of identification was also demonstrated by this dissection (Figs. 1 and 2). The first part of the radiologic study revealed that the styloid base is consistently present in all the 200 temporal bone images studied (100%). In 81% of the cases, the length of the styloid process was > 2 cm; in 13% of the cases, the length was between 1 and 2 cm, and in 3% of the cases it was < 1 cm from the styloid base (Fig. 3). The distance between the styloid base and the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle studied on 3D CT scans of 25 subjects (Fig. 4) showed that this distance ranged from 0.45 cm to 0.99 cm (mean: 0.72 cm) (Fig. 5). The clinical study done in 25 adult patients who underwent parotidectomy showed that the landmarks were consistent in all patients. The styloid base and the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle could be identified safely using the method described, and the facial nerve was found to be emerging in between these two in all 25 patients (Fig. 6). None of the patients developed an inadvertent facial nerve injury related to the technique of identification of the facial nerve.

Fig. 1.

Cadaver dissection of right side parotid region, demonstrating styloid base, origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the facial nerve emerging between them. EAC, external auditory canal.

Fig. 2.

Yellow lines with arrows represent the trident appearance of the landmark on the dissected cadaver specimen. EAC, external auditory canal.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients with varying length of the styloid process assessed by imaging of 200 temporal styloid processes.

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of temporal bone showing the distance between the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric from the digastric ridge to the base of styloid process, measured using Osirix software.

Fig. 5.

Chart showing the distance between the styloid base and the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle measured in three-dimensional computed tomography scans of the temporal bones.

Fig. 6.

Surgical demonstration of the styloid base, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the facial nerve emerging between them.

Discussion

Although multiple landmarks have been described for facial nerve identification in parotid surgery, almost all of the existing landmarks are described as single landmarks. Perhaps the most common landmark used to identify the extratemporal facial nerve is the tragal pointer. The depth from the tragal pointer to the facial nerve has been variably described as 1 to 3 cm by various authors; the width has not been described. This was found to be 34 mm from the tragal pointer in a cadaveric study by Pather and Osman.2 So for surgeons, especially beginners, identification of the facial nerve becomes time consuming and difficult.

Various authors have criticized the direction of the facial nerve from the tragal pointer because it is a cartilaginous, mobile, and asymmetric landmark with a blunt, irregular tip.1 6 7 This is a cause of difficulty, especially for less experienced surgeons, because the direction of the tragal pointer is not interpreted identically by surgeons. Another landmark for the identification of the facial nerve, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, also has received similar criticisms because it is also a flexible landmark subject to retraction.2 7 The styloid process is another landmark used to identify the facial nerve. A morphological study on cadavers, panoramic radiographs, and dry skulls tried to determine the mean length of the styloid process and found it to be 22.54 ± 4.24, showing no significant difference in length between the right and left sides.8 Although the styloid process has the advantage of being very close to the facial nerve, it has fallen out of favor because the nerve can be superficial to the styloid process, and the styloid process itself can be small or absent in a proportion of cases.3 4 9 The stylomastoid artery also has been described as a landmark to identify the facial nerve but has not become popular, probably due to the inconsistent presence and anatomical variations reported by some authors themselves.10

Another landmark that has been described is the transverse process of axis. The arguments in favor of this landmark are that it is easily palpated, does not require complex dissection, and ensures a minimum risk of injury to the facial nerve.2 But this is not a landmark that needs to be dissected during a parotid surgery, and the direction of the facial nerve cannot be clearly predicted. This is probably why most surgeons are not using it as a landmark.

Some authors have described the TMS as the best landmark to identify the facial nerve trunk because it is easy to find, its position is invariable, and its relation to the nerve reliable because it leads to the stylomastoid foramen.3 5 9 11 But there are lot of objections; some authors claim that using the TMS as a landmark increases the complexity of the surgical intervention because it requires elevation of the periosteum around the ear canal and dissection inferiorly to reach it.2 12 13 Studies by Browne and by Pather and Osman concluded that the TMS is obscured by the strong tendon of the sternocleidomastoid muscle inserted into the lateral surface of the mastoid process from its apex to its superior border.2 13

Another landmark described is the most posterior point of the ramus of the mandible,14 but the distance between the facial nerve and this point was found to be between 25.3 and 48.69 mm in a cadaveric study.2 The variability of the mandible between males and females has also been pointed out, so most surgeons do not prefer it. In a cadaveric study, Pereira et al suggested external palpable landmarks to identify the facial nerve and proposed that the facial nerve can be identified in the center of a triangle formed by the temporomandibular joint, the mastoid process, and the angle of the mandible.15 Bony landmarks to identify the facial nerve were proposed in another cadaveric study.16 The usefulness of these approaches in live surgery has not been tested.

In the present study, the facial nerve is described between two fixed bony landmarks: the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle from the digastric notch of the mastoid and the base of the styloid process. The arguments against the styloid process do not hold in the case of the styloid base not because the facial nerve may be superficial to the anterior part of the styloid process, but because the stylomastoid foramen is under the base of the styloid, the facial nerve is always deep to it and emerges anteriorly. Identification of the styloid base is also easy and safe via the method used in this study, where the dissection to the styloid base is always guided by the cartilage and bony resistance of the tragus and bony EAC wall. It may be noted that the muscles attach to the styloid process more distally, which is developmentally the stylohyal part.5 Maintaining a superior to inferior trajectory along the EAC while trying to identify the base of the styloid process would ensure further safety in dissection. The styloid base can also help the surgeon certain regarding the depth of the facial nerve because the dissection need not be continued beyond this, unlike the case of landmarks like the tragal pointer where the surgeon is unsure of the depth of dissection. Identification of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle is also safe as long as dissection does not extend above the superior border of the muscle. The soft tissue between the superior border of the posterior belly of the digastric and styloid base can be dissected safely until the level of the digastric muscle. Deeper to this the surgeon has to be careful because the facial nerve is very close. Dissection should be done in a direction parallel to the central prong of the trident, that is, the nerve. Care should be taken not to cause any undue bleeding because the stylomastoid artery may be encountered near this region.

Study Limitations

The method described here has not been studied in reoperations of the parotid region and congenital anomalies of the head and neck areas. Even in these difficult cases the landmark described here may be of help because the facial nerve is localized between two fixed bony points. But caution should be exercised to avoid anatomical surprises in such cases. Also, this method has not been tested in children.

Conclusion

The trident landmark described here allows for the safe and relatively easy identification of two fixed bony landmarks and narrows down the area of identification of the facial nerve between them. The base of the styloid is consistently present and also sets the depth beyond which dissection need not be performed. According to the results of our radiologic, cadaveric, and clinical study, we conclude that the landmark described here is one of the most accurate, safe, and easy methods so far described to identify the facial nerve during parotid surgery. This can be a very useful method for training junior surgeons in facial nerve identification.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Prof. (Dr.) Mini Pillai and Mr. Suresh, Department of Anatomy, AIMS, Kochi, and Dr. Akanksha Saxena, Department of ENT, AIMS, Kochi.

References

- 1.de Ru J A, van Benthem P P, Bleys R L, Lubsen H, Hordijk G J. Landmarks for parotid gland surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115(2):122–125. doi: 10.1258/0022215011907721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pather N, Osman M. Landmarks of the facial nerve: implications for parotidectomy. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28(2):170–175. doi: 10.1007/s00276-005-0070-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabb H G, Scalco A N, Fraser S F. Exposure of the facial nerve in parotid surgery. (Use of the tympanomastoid fissure as a guide) Laryngoscope. 1970;80(4):559–567. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beahrs O H. The surgical anatomy and technique of parotidectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1977;57(3):477–493. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray H Anatomy of the Human Body Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1918; Bartleby.com; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Ru J A Bleys R L van Benthem P P Hordijk G J Preoperative determination of the location of parotid gland tumors by analysis of the position of the facial nerve J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001595525–528.; discussion 529–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trible W M. Symposium: management of tumors of the parotid gland. III. Management of the facial nerve. Laryngoscope. 1976;86(1):25–27. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balcioglu H A, Kilic C, Akyol M, Ozan H, Kokten G. Length of the styloid process and anatomical implications for Eagle's syndrome. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2009;68(4):265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conley J, Hamaker R C. Prognosis of malignant tumors of the parotid gland with facial paralysis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1975;101(1):39–41. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1975.00780300043012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upile T, Jerjes W, Nouraei S A. et al. The stylomastoid artery as an anatomical landmark to the facial nerve during parotid surgery: a clinico-anatomic study. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witt R L. Facial nerve function after partial superficial parotidectomy: an 11-year review (1987–1997) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(3):210–213. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishida M, Matsuura H. A landmark for facial nerve identification during parotid surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51(4):451–453. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browne H J. Exposure of the facial nerve. Br J Surg. 1988;75(7):724–725. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conn I G, Wiesenfeld D, Ferguson M M. The anatomy of the facial nerve in relation to CT/sialography of the parotid gland. Br J Radiol. 1983;56(672):901–905. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-56-672-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira J A Merí A Potau J M Prats-Galino A Sancho J J Sitges-Serra A A simple method for safe identification of the facial nerve using palpable landmarks Arch Surg 20041397745–747.; discussion 748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greyling L M, Glanvill R, Boon J M. et al. Bony landmarks as an aid for intraoperative facial nerve identification. Clin Anat. 2007;20(7):739–744. doi: 10.1002/ca.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]