Abstract

Background

Lead V1 on electrocardiography (ECG) can detect the dominant frequency (DF) of atrial fibrillation (AF) in the right atrium (RA). Paroxysmal AF is characterized by a frequency gradient from the left atrium (LA) to the right atrium (RA). We examined the ability of magnetocardiography (MCG) to detect regional DFs in both the atria.

Methods

Study subjects comprised 18 consecutive patients referred for catheter ablation of persistent AF. An MCG system with 64 magnetic sensors was used to perform MCG in the frontal, lateral, and back planes prior to the ablation procedure in each patient. DFMCG and organization index (OIMCG) were calculated using fast Fourier transformation. Intracardiac electrograms (ICEs) in both the atria and the coronary sinus (CS) were mapped at 17 sites. Regional DFsICE were also determined.

Results

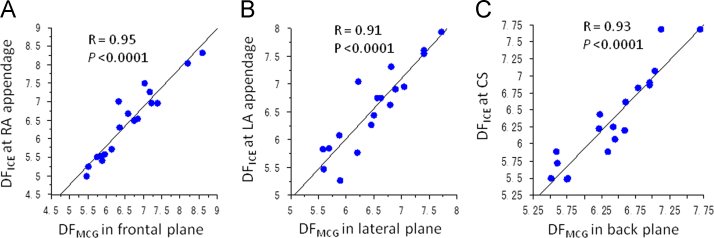

Mean LA DFICE was higher than mean RA DFICE (6.40±0.66 versus 6.16±0.80 Hz, P=0.03). DFMCG in the channel having the highest OIMCG was 6.61±0.88 Hz in the frontal plane, 6.52±0.64 Hz in the lateral plane, and 6.42±0.62 Hz in the back plane (P=0.3). In each plane, DFMCG correlated with DFICE at the RA appendage (R=0.95, P<0.0001), the LA appendage (R=0.91, P<0.0001), and the CS (R=0.93, P<0.0001). DFECG in V5 modestly correlated with DFICE at the LA appendage (R=0.82, P<0.0001).

Conclusions

MCG could more precisely detect the DFs in the LA and the CS than ECG. However, the usefulness of pre-procedural detection of the AF frequency gradient for ablation therapy needs to be evaluated in future prospective studies.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Magnetocardiography, Dominant frequency

1. Introduction

Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AF) has rapidly evolved in this decade, and pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is currently a well-standardized technique for treating paroxysmal AF. However, in patients with persistent AF, ablation therapy is still challenging because the arrhythmogenic substrate beyond the pulmonary veins (PVs) plays a role in the perpetuation of AF [1], [2], [3]. A tailored treatment approach for each AF patient seems reasonable owing to the multifactorial and progressive nature of AF. One factor that characterizes AF is the dominant frequency (DF). The DF is closely related to atrial refractoriness and degree of electrical remodeling [4]. A frequency gradient from the left atrium (LA) to the right atrium (RA) characterizes paroxysmal AF [5]. Patients with a rare type of AF with a right-to-left frequency gradient may suffer from a right atrial substrate and may be maintained on a right atrial driver. Therefore, measurement of regional DFs can be used as a guide to tailor an ablation strategy [6], [7], [8].

Magnetocardiography (MCG) is a body surface mapping method that noninvasively detects the magnetic field of the heart. Notably, the electrocardiography (ECG) signal is affected by interpatient differences in body characteristics and other physiological parameters, whereas the magnetic field is not distorted by its flow through the tissues such as lungs, muscles, and bones. This unique characteristic of magnetic fields results in better spatial resolution in MCG than in ECG [9]. Although it is well known that lead V1 on the ECG reflects RA DF [10], [11], little is known about the ability of MCG to detect regional DFs in the atria. As the standard ECG leads are not specifically designed to record atrial activity, the multichannel and multiplane recording method of MCG (64 channels×3 planes) might offer an advantage over the standard ECG method in detecting atrial DFs. This study evaluated the relationship between DFs in the atria measured by MCG mapping and those measured by multisite intracardiac mapping.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study subjects

Study subjects comprised 18 consecutive patients referred for catheter ablation of persistent AF. Patients who had undergone a prior ablation procedure, those with structural heart disease, or those with a history of heart failure were excluded from the study. The clinical characteristics of the study subjects are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

| Characteristic | Study subjects (N=18) |

|---|---|

| Sex (Female) | 6 (33%) |

| Age | 60±9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25±3 |

| Hypertension | 10 (56%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (17%) |

| Duration of AF history (months) | Median=7, IQR=8 |

| LVEF (%) | 62 ±8 |

| LAVi (mL/m2) | 38±12 |

AF=atrial fibrillation, IQR=interquartile range, LAVi=left atrial volume indexed to body surface area, LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction.

2.2. Measurement and analysis of MCG signals

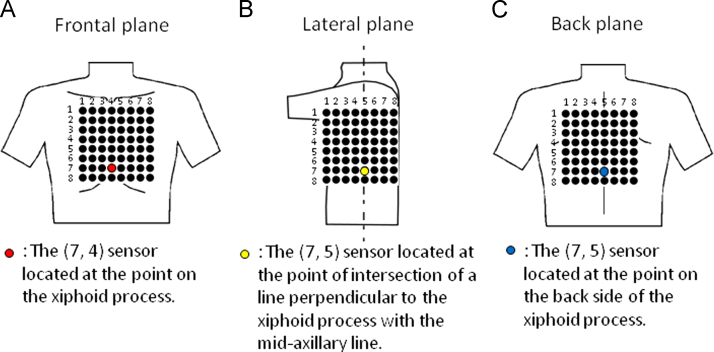

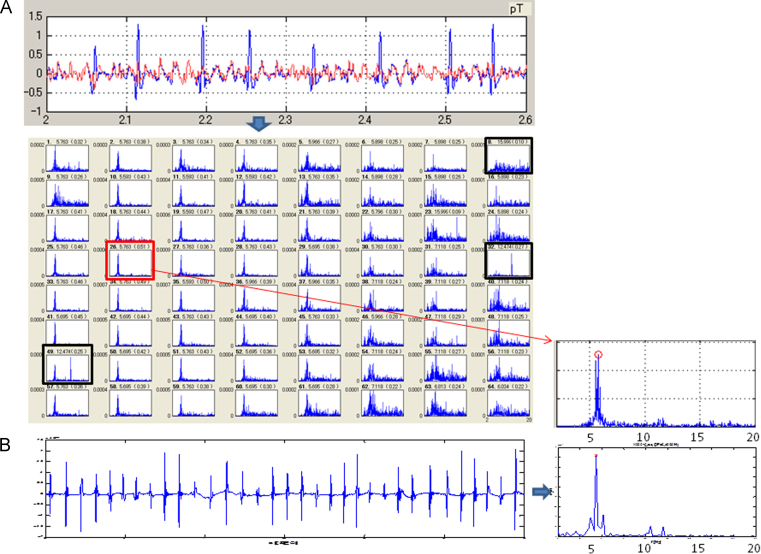

The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board, and all patients provided their informed written consent. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy was discontinued 4–5 half-lives before the procedure. All patients underwent MCG during AF 1 day before the procedure. MCG methodology has been described in detail in a previous study [12]. We used an MCG system (MC-6400, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with 64 magnetic sensors to measure the magnetic field. The magnetic field sensors were in an 8 × 8 matrix with a pitch of 25 mm, and the measurement area was 175×175 mm2 (Fig. 1). The MCG signals for each subject in the resting state were recorded in 3 planes (frontal, lateral, and back) in a magnetically shielded room. For the frontal MCG measurement, the subject lay supine on the bed, and the (7, 4) sensor was placed above the xiphoid process (Fig. 1A). For the lateral MCG measurement, the subject lay on the right side, and the (7, 5) sensor was placed at the point of intersection of the line perpendicular to the xiphoid process with the midaxillary line (Fig. 1B). For the back MCG measurement, the subject was turned to the prone position, and the (7, 5) sensor was placed on the back side of the xiphoid process (Fig. 1C). A total of 3456 channels (64 channels×3 planes×18 patients) were analyzed. The sampling rate was 1 kHz, and the measurement period was 2 min. ECG leads II, V1, and V5 were simultaneously recorded throughout the procedure. The MCG signals were passed through a bandpass filter (0.1 to 50 Hz) and a power line noise filter (50 Hz). To analyze the MCG signals generated from an atrial electrical activation, we subtracted QRS-complex and T-wave signals from the measured MCG signals using the template QRS-T waveform (Fig. 2A) [13]. Furthermore, we calculated the power spectrum of the QRS-subtracted MCG signals using fast Fourier transform (FFT) techniques. The highest peak of the power spectrum in the range of 0.5 to 20 Hz was defined as the DF (Fig. 2B). Sites with DFs beyond the biological range (3–12 Hz) were excluded from further analysis [14]. To quantify the regularity of AF, the organization index (OI) was calculated as the ratio of the total area of the spectrum under the first five harmonic peaks to the total area of the spectrum [15].

Fig. 1.

Relative position of the marker sensor to the body in the frontal (A), lateral (B), and back (C) planes.

Fig. 2.

(A) (Upper panel) Subtraction of QRS complex from the measured MCG signals in the lateral plane. The blue line shows the original MCG signals recorded for 6 s during AF. The red line shows the residual F waves after subtracting the QRS complex. (Lower panel) Periodograms corresponding to all 64 channels. The black rectangles are the excluded periodograms having DFs out of the biological range. The red rectangle indicates the periodogram having the highest OI among the 64 channels (DF=5.76 Hz, OI=0.51). (B) (Left panel) Intracardiac electrograms recorded at the LAA for 6 s. (Right panel) The DF and OI are 5.50 Hz and 0.45, respectively. The periodogram corresponding to the electrograms recorded at the LAA is in good agreement with that corresponding to the MCG signal in the lateral plane. AF=atrial fibrillation; DF=dominant frequency; LAA=left atrial appendage; MCG=magnetocardiography; OI=organization index.

2.3. Measurements and analysis of intracardiac electrograms (ICEs)

All patients presented to the laboratory in AF. After the transseptal puncture, electroanatomical mapping (CARTO, Biosense-Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) was performed during AF before ablation. An open-irrigation, 3.5-mm-tip deflectable catheter (ThermoCool, Biosense-Webster) was used for mapping. Electrograms of ≥6-s duration were recorded in 17 bi-atrial regions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between DFICE and DFMCG, and between DFICE and DFECG at the 17 mapped sites.

| Frontal plane |

Lateral plane |

Back plane |

V1 |

V5 |

II |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | ||

| Right atrium | Appendage | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.63 | 0.005 | 0.76 | 0.0002 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.64 | 0.004 | 0.85 | <0.0001 |

| Septum | 0.78 | 0.0002 | 0.69 | 0.002 | 0.8 | 0.0001 | 0.78 | 0.0002 | 0.76 | 0.0004 | 0.85 | <0.0001 | |

| CTI | 0.77 | 0.0005 | 0.71 | 0.002 | 0.75 | 0.0007 | 0.83 | <0.0001 | 0.77 | 0.0004 | 0.67 | 0.004 | |

| Lateral wall | 0.88 | <0.0001 | 0.7 | 0.001 | 0.73 | 0.0005 | 0.89 | <0.0001 | 0.79 | <0.0001 | 0.82 | <0.0001 | |

| Posterior wall | 0.75 | 0.0004 | 0.66 | 0.003 | 0.76 | 0.0004 | 0.84 | <0.0001 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.009 | |

| Left atrium | RSPV antrum | 0.28 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.009 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.04 |

| RIPV antrum | 0.43 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.0005 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.009 | 0.53 | 0.02 | |

| LSPV antrum | 0.65 | 0.006 | 0.8 | 0.0002 | 0.79 | 0.0002 | 0.66 | 0.006 | 0.68 | 0.004 | 0.78 | 0.0004 | |

| LIPV antrum | 0.41 | 0.1 | 0.68 | 0.002 | 0.62 | 0.007 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.005 | |

| Posterior wall | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.1 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.2 | |

| Base of LAA | 0.62 | 0.008 | 0.89 | <0.0001 | 0.83 | <0.0001 | 0.68 | 0.002 | 0.78 | 0.002 | 0.72 | 0.0006 | |

| Roof | 0.6 | 0.008 | 0.77 | 0.0001 | 0.68 | 0.002 | 0.66 | 0.003 | 0.7 | 0.001 | 0.75 | 0.0003 | |

| Septum | 0.73 | 0.0006 | 0.75 | 0.0003 | 0.79 | <0.0001 | 0.78 | 0.0001 | 0.73 | 0.0006 | 0.77 | 0.0002 | |

| Mitral isthmus | 0.81 | <0.0001 | 0.83 | <0.0001 | 0.89 | <0.0001 | 0.8 | <0.0001 | 0.81 | <0.0001 | 0.92 | <0.0001 | |

| Inferior wall | 0.59 | 0.01 | 0.8 | <0.0001 | 0.71 | 0.002 | 0.68 | 0.002 | 0.73 | 0.0008 | 0.66 | 0.003 | |

| Appendage | 0.69 | 0.002 | 0.91 | <0.0001 | 0.79 | <0.0001 | 0.73 | 0.0005 | 0.82 | <0.0001 | 0.74 | 0.0003 | |

| Coronary sinus | 0.73 | 0.0006 | 0.79 | <0.0001 | 0.93 | <0.0001 | 0.74 | 0.0004 | 0.67 | 0.002 | 0.85 | <0.0001 | |

CTI=cavotricuspid isthmus; DF=dominant frequency; ECG=electrocardiography; ICE=intracardiac electrogram; LAA=left atrial appendage; LS=left superior; LI=left inferior; MCG=magnetocardiography; PV=pulmonary vein; RI=right inferior; RS=right superior.

Maximal R value in each plane or lead is highlighted in bold.

The details of the spectral analysis have been described in a previous study [7]. In brief, bipolar electrograms recorded for 6 s were processed off-line in the MatLab environment (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). The electrogram voltage was defined as the mean of a maximum of 10 electrogram amplitudes in a sampling window of 6 s [16]. The preprocessing steps in the spectral analysis included bandpass filtering with cutoffs at 40 and 250 Hz, rectification, and low-pass filtering with a cutoff at 20 Hz [17]. The definitions of DF and OI were the same as used in MCG analyses (Fig. 2A and B).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with normal distribution are expressed as mean±1 standard deviation and were compared using the Student t-test or paired t-test. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the continuous variables among multiple groups. Post-hoc analyses were performed using the Scheffé test. To determine the relationship between DF measured by MCG (DFMCG) and DF measured by ICE (DFICE), an independent Pearson׳s correlation coefficient was calculated for each of the 17 sites sampled. To account for these multiple comparisons, P values were corrected using the Bonferroni correction. Thus, the relationship was deemed significant at the 0.05 level if the P value was <0.0029 (i.e., 0.05/17).

3. Results

3.1. DF, OI, and voltage measured by ICE mapping (DFICE and OIICE)

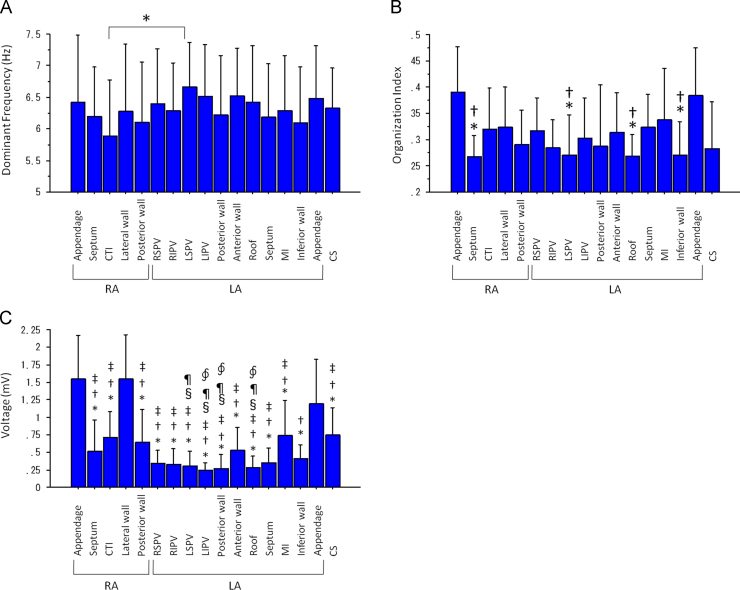

Mean LA DFICE was significantly higher than the mean RA DFICE (6.40±0.66 versus 6.16±0.80 Hz, P=0.03). However, regional differences in DFICE were significant only between DFICE at the cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) and at the left superior PV antrum (5.88±0.89 versus 6.66±0.71 Hz, P<0.05) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

(A) DFs at the 17 mapped sites (⁎P<0.05). (B) OI at the 17 mapped sites. (⁎P<0.05 versus OI at the RAA, †P<0.05 versus OI at the LAA). (C) Voltage at the 17 mapped sites (⁎P<0.05 versus voltage at the RAA, †P<0.05 versus voltage at the LAA, ‡P<0.05 versus voltage at the RA lateral wall, §P<0.05 versus voltage at the mitral isthmus and P<0.05 versus voltage at the CS, ∮P<0.05 versus voltage at the CTI). CS=coronary sinus; CTI=cavotricuspid isthmus; DF=dominant frequency; LA=left atrium; LAA=left atrial appendage; LIPV=left inferior pulmonary vein antrum; LSPV=left superior pulmonary vein antrum; MI=mitral isthmus; RA=right atrium; RAA=right atrial appendage; RIPV=right inferior pulmonary vein antrum; RSPV=right superior pulmonary vein antrum.

There was no significant difference in OIICE between the right and the left atrium (0.30±0.04 versus 0.31±0.05, P=0.3). However, there were significant regional differences in OIICE among the 17 mapped sites (P=0.0001). The OIICE values at the RA appendage (RAA) and the LA appendage (LAA) were significantly higher than those at the RA septum, the LA roof, the left superior PV antrum, and the LA inferior wall (Fig. 3B).

The mean LA voltage was significantly lower than the mean RA voltage (0.44±0.18 versus 0.94±0.36 mV, P<0.0001). There were significant regional differences in voltage among the 17 mapped sites (P<0.0001). In particular, the values at the LAA, the RAA, and the lower lateral RA were higher than those at the other mapped sites (Fig. 3C).

3.2. DF and OI measured by MCG mapping (DFMCG and OIMCG)

The mean DFMCG in the 64 channels in the study group was 6.56±0.75 Hz in the frontal plane, 6.49±0.52 Hz in the lateral plane, and 6.52±0.60 Hz in the back plane (P=0.9). The DFMCG in the channel having the highest OI in each plane was 6.61±0.88 Hz, 6.52±0.64 Hz, and 6.42±0.62 Hz, respectively (P=0.3).

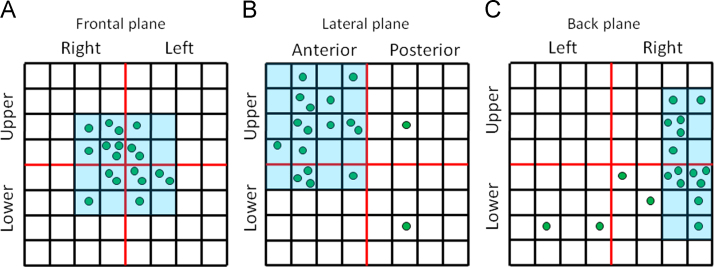

Mean OIMCG in the frontal plane (0.36±0.09) was significantly higher than that in the lateral (0.24±0.05) and the back planes (0.27±0.05) (P<0.0001). Maximum OIMCG among the 64 channels in each plane was 0.47±0.11, 0.33±0.09, and 0.37±0.08, respectively (P<0.0001). The sites having the highest OI were distributed in a cluster (Fig. 4). The sites having the highest OI in the frontal plane were located predominantly in the center of the detection area, those in the lateral plane were located in the upper anterior area, and those in the back plane were located in the right side (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of the detection sites having the highest OI in the frontal (A), lateral (B), and back planes (C). Note that these sites are localized within a particularly small area in the three planes. OI=organization index.

3.3. Relationship between DFMCG and DFICE

Mean RA DFICE and mean LA DFICE correlated modestly with mean DFMCG in the frontal plane (R=0.89, P<0.0001) and in the back plane (R=0.87, P<0.0001), respectively. The DF having the highest OI in the frontal plane correlated most strongly with the DFICE at the RAA (R=0.95, P<0.0001) (Fig. 5A and Table 2), that in the lateral plane correlated most strongly with the DFICE at the LAA (R=0.91, P<0.0001) (Fig. 5B and Table 2), and that in the back plane correlated most strongly with the DF in the CS (R=0.93, P<0.0001) (Fig. 5C and Table 2).

Fig. 5.

The correlation between the DFMCG in the frontal plane and the DFICE at the RAA (A), between the DFMCG in the lateral plane and the DFICE at the LAA (B), and between the DFMCG in the back plane and the DFICE in the CS (C). CS=coronary sinus; DF=dominant frequency; ICE=intracardiac electrogram; LA=left atrium; LAA=left atrial appendage; MCG=magnetocardiography; RA=right atrium; RAA=right atrial appendage.

3.4. Relationship between OIMCG and OIICE

Mean OIMCG in the frontal plane correlated with OIICE at the RAA (R=0.49, P<0.05), and that in the lateral and the back planes correlated with OIICE at the LAA (R=0.73, P=0.001 and R=0.65, P=0.004, respectively) and the CS (R=0.66, P=0.007 and R=0.56, P=0.01, respectively). The maximum OIMCG in the frontal and the lateral planes correlated with the OIICE at the RAA (R=0.50, P=0.03) and the LAA (R=0.73, P=0.001), respectively, and that in the back plane did not correlate with the OIICE in the CS (R=0.38, P=0.12).

3.5. DF and OI measured by ECG (DFECG and OIECG)

The DFECG was 6.52±0.89 Hz in V1, 6.33±0.73 Hz in V5, and 6.57±0.77 Hz in lead II (P=0.2). The DFECG in V1 correlated with DFICE in the RA, especially with the DFICE at the RAA (R=0.95, P<0.0001) (Table 2). The DFECG in V5 modestly correlated with the DFICE at the LAA (R=0.82, P<0.0001). This correlation was weaker than the correlation between the DFMCG in the lateral plane and the DFICE at the LAA (R=0.91, P<0.0001) (Table 2). The DFECG in II correlated most strongly with the DFICE at the mitral isthmus (R=0.92, P<0.0001) (Table 1).

The OIECG in V1 was significantly higher than that in V5 and II (0.43±0.09 in V1, 0.31±0.02 in V5, 0.36±0.07 in II, P<0.0001 for both). The OIECG in leads V1, V5, and II did not correlate with OIICE at any of the 17 mapped sites.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

The DFMCG having the highest OI in the frontal, lateral, and back planes correlated strongly with the DFICE at the RAA, the LAA, and the CS, respectively. As expected, these sites were localized within a particularly small area in the MCG sensor. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that MCG can more precisely detect the DFs in the LA and the CS than ECG. This may allow us to noninvasively detect the frequency gradient between the LA and the RA that characterizes the dynamics and mechanisms of AF.

4.2. Accuracy of measurements of DFs

Many previous studies agree that ECG lead V1 can accurately detect the electrical activity in the RA due to the lead׳s proximity to the RA [10], [11]. In our study too, the DF in lead V1 correlated strongly with the RA DF.

However, earlier studies do not agree on whether the lateral ECG leads (I, aVL, and V4–6) can detect LA DF or cycle length. Only 2 studies have reported that the lateral ECG leads can detect LA DF (or cycle length) [18], [19]. To overcome the limitation of detecting LA DF using the standard ECG lead positions, Petrutiu et al. [11] had put an ECG lead on the patient׳s back and had showed that this posterior lead is better at detecting LA DF than the standard leads. However, in our study, the accuracy of lead V5 in detecting LA DF was only modest and was lower than that of MCG. Possible explanations of this discrepancy are the differences in the methodology (frequency domain analysis using FFT versus time domain analysis using autocorrelation method, 3.5-mm-tip catheter versus basket catheter) [19] and in the degree of structural remodeling in the study subjects. In our study, all patients had persistent AF and the LA was moderately enlarged. Posterior displacement of an enlarged LA makes the LA move away from the precordial leads. Moreover, low voltage in the LA due to advanced structural remodeling may make measurements of DFs less accurate because of increased noise-to-signal ratio. MCG measurements may be less affected by an enlarged LA and decreased voltage because the magnetic field does not attenuate through the tissues existing between the LA and the MCG sensor.

The MCG measurement in the back plane could accurately detect CS DF. Besides, ECG lead II correlated strongly with the DF at the mitral isthmus/CS region. Although the inferior ECG leads are considered to be useful in detecting the DF at the inferior LA including the CS, [19] it was an unexpected and interesting result that the MCG measurement in the back plane has the potential to detect the CS DF using the standard FFT method even in patients with advanced structural remodeling.

4.3. Mechanism of detecting regional DFs using an MCG

So far, it is unclear how activities from different parts of the atria contribute to the MCG recordings. In this study, the DFMCG having the highest OIMCG correlated strongly with the DFICE at the LAA, the RAA, and the CS. In the frontal plane, the RAA is anatomically adjacent to the MCG sensor. Its voltage was significantly higher than that of the RA septum and the posterior wall. More importantly, the OI of the RAA was the highest among the RA sites. Similarly, in the lateral plane, the LAA is anatomically adjacent to the MCG sensor. Both the voltage and the OI at the LAA were the highest among the LA sites. These anatomical and electrical characteristics of the appendages may contribute to strong correlations between the DFs at the appendages and the DFs in the channels having the highest OI. Finally, in the back plane, the posterior wall, the PV antra, and the CS are anatomically close to the MCG sensor. Although there was no difference in the OI among the 3 regions, the voltages in the CS were significantly higher than those at the other sites. Markedly, the CS is the only structure located in the epicardium. Moreover, a recent animal study has shown that there is dissociation of electrical activation and direction of conduction vectors of AF electrograms between the epicardium and the endocardium [20]. These facts may explain why the site having the highest OI in the back plane correlated strongly with the CS DF.

Notably, the sites of interest having the highest OI were distributed within a particularly small region of the MCG sensor. This result corroborates the significance of the anatomical relationship between the appendages and the MCG sensor. Moreover, adjusting the location of the sensor according to the location of the cluster region may be a simple way in clinical practice to make measurements of DFs more accurate.

4.4. Clinical implication

DF can be a surrogate for the degree of atrial electrical remodeling [4], [21]. Further, it identifies patients who may require additional ablation beyond PVI [8], [22]. In an animal study by Mansour et al., acute AF in an isolated sheep heart had a left-to-right frequency gradient [23]. Based on this finding, the authors hypothesized that high-frequency periodic sources located in the LA drive AF. A human study confirmed that there is a left-to-right frequency gradient during paroxysmal AF, but not during persistent AF. We recently found a rare type of AF that had its trigger and substrate in the right atrium (right AF). Such uncommon AF was characterized by a right-to-left frequency gradient and was cured by right atrial ablation (unpublished data). These previous studies and observations suggest that comparing the DFs in the RA and the LA before ablation may be helpful in predicting the mechanism of AF (e.g., whether it is PV-dependent), in designing an ablation strategy, and in informing patients about the possible procedural risks, benefits, and success rate.

4.5. Limitations

First, the MCG was performed separately from the intracardiac mapping because it requires a magnetically shielded room. However, the temporal stability of AF electrograms is reported to be high in persistent AF [10], [19], [24], [25].

Secondly, only patients with persistent AF were included in this study due to the practical difficulty of recording paroxysmal AF both during the MCG measurement and during the intracardiac mapping. Because a left-to-right DF gradient is not commonly observed in persistent AF, it was difficult to compare the DF gradient between the MCG recording and the intracardiac mapping in this study. A further study including the patients with paroxysmal AF and with a DF gradient is needed to clarify the clinical advantage of MCG over ECG.

5. Conclusion

MCG could more precisely detect the DFs in the LA and the CS than ECG. However, the usefulness of pre-procedural detection of the AF frequency gradient for ablation therapy needs to be evaluated in future prospective studies.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Haissaguerre M., Hocini M., Takahashi Y. Impact of catheter ablation of the coronary sinus on paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:378–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knecht S., Hocini M., Wright M. Left atrial linear lesions are required for successful treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2359–2366. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oral H., Chugh A., Yoshida K. A randomized assessment of the incremental role of ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms after antral pulmonary vein isolation for long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim K.B., Rodefeld M.D., Schuessler R.B. Relationship between local atrial fibrillation interval and refractory period in the isolated canine atrium. Circulation. 1996;94:2961–2967. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazar S., Dixit S., Marchlinski F.E. Presence of left-to-right atrial frequency gradient in paroxysmal but not persistent atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation. 2004;110:3181–3186. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147279.91094.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haissaguerre M., Sanders P., Hocini M. Changes in atrial fibrillation cycle length and inducibility during catheter ablation and their relation to outcome. Circulation. 2004;109:3007–3013. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130645.95357.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida K., Chugh A., Good E. A critical decrease in dominant frequency and clinical outcome after catheter ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hocini M., Nault I., Wright M. Disparate evolution of right and left atrial rate during ablation of long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart G. Biomagnetometry: imaging the heart׳s magnetic field. Br Heart J. 1991;65:61–62. doi: 10.1136/hrt.65.2.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu N.W., Lin Y.J., Tai C.T. Frequency analysis of the fibrillatory activity from surface ECG lead V1 and intracardiac recordings: implications for mapping of AF. Europace. 2008;10:438–443. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrutiu S., Sahakian A.V., Fisher W. Manifestation of left atrial events and interatrial frequency gradients in the surface electrocardiogram during atrial fibrillation: contributions from posterior leads. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:1231–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada S., Tsukada K., Miyashita T. Noninvasive, direct visualization of macro-reentrant circuits by using magnetocardiograms: initiation and persistence of atrial flutter. Europace. 2003;5:343–350. doi: 10.1016/s1099-5129(03)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kandori A., Hosono T., Kanagawa T. Detection of atrial-flutter and atrial-fibrillation waveforms by fetal magnetocardiogram. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2002;40:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02348127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bollmann A., Sonne K., Esperer H.D. Non-invasive assessment of fibrillatory activity in patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation using the Holter ECG. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:60–66. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everett T.H., 4th, Moorman J.R., Kok L.C. Assessment of global atrial fibrillation organization to optimize timing of atrial defibrillation. Circulation. 2001;103:2857–2861. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida K., Ulfarsson M., Oral H. Left atrial pressure and dominant frequency of atrial fibrillation in humans. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng J., Kadish A.H., Goldberger J.J. Effect of electrogram characteristics on the relationship of dominant frequency to atrial activation rate in atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1295–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dibs S.R., Ng J., Arora R. Spatiotemporal characterization of atrial activation in persistent human atrial fibrillation: multisite electrogram analysis and surface electrocardiographic correlations–a pilot study. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravi K.C., Krummen D.E., Tran A.J. Electrocardiographic measurements of regional atrial fibrillation cycle length. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32(Suppl 1):S66–S71. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.02229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckstein J., Maesen B., Linz D. Time course and mechanisms of endo-epicardial electrical dissociation during atrial fibrillation in the goat. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:816–824. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misier A.R., Opthof T., van Hemel N.M. Increased dispersion of "refractoriness" in patients with idiopathic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:1531–1535. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90614-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida K., Ulfarsson M., Tada H. Complex electrograms within the coronary sinus: time- and frequency-domain characteristics, effects of antral pulmonary vein isolation, and relationship to clinical outcome in patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1017–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansour M., Mandapati R., Berenfeld O. Left-to-right gradient of atrial frequencies during acute atrial fibrillation in the isolated sheep heart. Circulation. 2001;103:2631–2636. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.21.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bollmann A., Kanuru N.K., McTeague K.K. Frequency analysis of human atrial fibrillation using the surface electrocardiogram and its response to ibutilide. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:1439–1445. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xi Q., Sahakian A.V., Ng J. Atrial fibrillatory wave characteristics on surface electrogram: ECG to ECG repeatability over twenty-four hours in clinically stable patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:911–917. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]