Abstract

Sporothrix infections are emerging as an important human and animal threat among otherwise healthy patients, especially in Brazil and China. Correct identification of sporotrichosis agents is beneficial for epidemiological surveillance, enabling implementation of adequate public-health policies and guiding antifungal therapy. In areas of limited resources where sporotrichosis is endemic, high-throughput detection methods that are specific and sensitive are preferred over phenotypic methods that usually result in misidentification of closely related Sporothrix species. We sought to establish rolling circle amplification (RCA) as a low-cost screening tool for species-specific identification of human-pathogenic Sporothrix. We developed six species-specific padlock probes targeting polymorphisms in the gene encoding calmodulin. BLAST-searches revealed candidate probes that were conserved intraspecifically; no significant homology with sequences from humans, mice, plants or microorganisms outside members of Sporothrix were found. The accuracy of our RCA-based assay was demonstrated through the specificity of probe-template binding to 25 S. brasiliensis, 58 S. schenckii, 5 S. globosa, 1 S. luriei, 4 S. mexicana, and 3 S. pallida samples. No cross reactivity between closely related species was evident in vitro, and padlock probes yielded 100% specificity and sensitivity down to 3 × 106 copies of the target sequence. RCA-based speciation matched identifications via phylogenetic analysis of the gene encoding calmodulin and the rDNA operon (kappa 1.0; 95% confidence interval 1.0-1.0), supporting its use as a reliable alternative to DNA sequencing. This method is a powerful tool for rapid identification and specific detection of medically relevant Sporothrix, and due to its robustness has potential for ecological studies.

Keywords: sporotrichosis, diagnostics, PCR, epidemiology, Sporothrix, calmodulin, RCA, identification

Introduction

Sporotrichosis is a chronic fungal infection of humans and animals and is one of the most prevalent (sub)cutaneous mycoses in temperate and subtropical regions of the globe (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). The most probable route of acquisition of the disease is through traumatic introduction of Sporothrix propagules into the tissue of the warm-blooded host (De Hoog et al., 2000). The eco-epidemiology of Sporothrix species is exceptional in the fungal kingdom due to their frequent epidemic manifestation as large sapronoses or zoonoses (Rodrigues et al., 2013b). The classical environmental route of transmission, which was described more than a century ago, involves traumatic implantation of Sporothrix into human skin, usually via contaminated soil or plant material (Zhang et al., 2015). In the alternative route, direct horizontal animal transmission of Sporothrix occurs among cats and can lead to zoonotic transmission (cat-to-human), usually via deep scratches and bites from diseased cats (Rodrigues et al., 2014d; Gremião et al., 2015).

Technical developments in investigating the taxonomy of the S. schenckii clade have enabled the routine clinical recognition of S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii s. str., S. globosa, and S. luriei (Marimon et al., 2006, 2007, 2008a). These taxonomical improvements were essential for uncovering important aspects related to species distribution and population structure (Rodrigues et al., 2013b, 2014d), different levels of virulence (Fernandes et al., 2013), host-parasite interplay (Rodrigues et al., 2015c), and varying sensitivities to antifungals (Rodrigues et al., 2014c). The emergence of sporotrichosis in areas where the number of cases remained near baseline for long periods has highlighted the threat of cross-species pathogen transmission, for example of the cat-borne, highly pathogenic clonal offshoot S. brasiliensis (Rodrigues et al., 2013b, 2014d, 2015c). On the other hand, the cosmopolitan S. globosa is often recovered from human cases after contamination during agricultural practice in Asia (Zhou et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). Different ecological behaviors resulting in distinct routes of contamination underline the importance of strain typing, yet also highlight the need for well-conducted epidemiological investigations to better understand the dynamics and the source of these pathogens in nature.

Sporothrix brasiliensis is by far the most virulent species in the clinical clade (Arrillaga-Moncrieff et al., 2009; Fernandes et al., 2013) and is usually related to atypical and more severe clinical manifestation in humans and animals (Almeida-Paes et al., 2014). Recent studies indicated a great proportion of itraconazole-resistant isolates of S. brasiliensis during outbreaks. Prolonged exposure to the drugs associated with the clonal population structure during epidemics may be related to the emergence of drug insensitive S. brasiliensis isolates. These isolates are continuously spread throughout direct horizontal animal transmission and via zoonotic transmission (Rodrigues et al., 2014c; Borba-Santos et al., 2015; Teixeira et al., 2015). On the other hand, S. schenckii presents with a great genetic diversity what is reflected in distinct virulence profiles from low to highly pathogenic genotypes (Arrillaga-Moncrieff et al., 2009; Fernandes et al., 2013) as well it shows a broad in vitro susceptibility to azoles (Rodrigues et al., 2014c). Species embedded in the environmental clade such as S. pallida, S. mexicana, and S. chilensis lack pathogenicity to mammals (Arrillaga-Moncrieff et al., 2009; Rodrigues et al., 2015a) and are usually tolerant to most of the antifungal drugs including azoles (Marimon et al., 2008b; Rodrigues et al., 2014c). Species identification may therefore guide specific treatment, improve our ability to adjust therapeutic regimens and reduce relapse.

Clinically relevant and environmental Sporothrix species are endowed with a remarkable phenotypic plasticity, discouraging the use of morphology alone for species identification. This limitation is especially true for agents in the S. schenckii clade (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) (Camacho et al., 2015; Rodrigues et al., 2015a). Uncertainties resulting from classical methods, e.g., assimilation of carbons sources, growth temperature, and micromorphology, highlight the urgent need for development of sensitive and accurate molecular methods for identifying these agents.

The gold standard for identifying species in the S. schenckii clade is based on phylogenetic analysis of protein-coding loci, e.g., calmodulin (Marimon et al., 2007), beta-tubulin (Rodrigues et al., 2015a), and translation elongation factor (Rodrigues et al., 2013b; Zhang et al., 2015), as well as the rRNA operon (Zhou et al., 2014). In an epidemic scenario in which hundreds to thousands of cases emerge, as in the long-lasting outbreaks of cat-transmitted sporotrichosis in southeastern Brazil (Rodrigues et al., 2013b) or during the large sapronosis in northeast China (Song et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015), DNA sequencing is financially unfeasible for processing a large number of samples. Currently, the major methods available for genotyping and identifying Sporothrix down to species level in the clinical laboratory include random amplified polymorphic DNA (Mesa-Arango et al., 2002), amplified fragment length polymorphisms (Zhang et al., 2015), PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) (Rodrigues et al., 2014b), species-specific PCR (Rodrigues et al., 2015b), and protein fingerprinting, for example via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (Oliveira et al., 2015). These methods are routinely implemented as the first means of identification. Limitations may include the need for isolated cultures, highly pure DNA preparations, and/or advanced instruments.

Methods based on the selective amplification and detection of very small quantities of nucleic acids are desirable for diagnosing sporotrichosis (Rodrigues et al., 2015b). Rolling circle amplification (RCA) was first introduced in the 1990s (Fire and Xu, 1995) as a simple and powerful technique for synthesizing large amounts of DNA from low starting concentrations. The method is particularly useful for signal amplification of padlock probes, linear DNA probes that become circularized upon recognition of a specific nucleic-acid sequence. The combination of padlock-probe circularization and amplification through RCA has proven useful for sensitive and specific detection of nucleic-acid sequences from pathogens (Zhang et al., 1998). RCA has gained much popularity in the identification of viral (Haible et al., 2006) and bacterial pathogens (Chen et al., 2014). Despite its limited use in mycological diagnosis, several studies have demonstrated the applicability of RCA for the molecular identification of medically relevant fungi such as Candida (Zhou et al., 2008), Aspergillus (Zhou et al., 2008), Trichophyton (Kong et al., 2008), Fonsecaea (Najafzadeh et al., 2011), Madurella (Ahmed et al., 2014), and Mucorales (Dolatabadi et al., 2014).

The aim of the present study was to establish a robust screening RCA-based assay for species-specific identification of S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii s. str., S. globosa, S. luriei, S. mexicana, and S. pallida. We describe the development, optimization, and validation of six species-specific padlock probes for identifying and detecting Sporothrix DNA. Improvements in RCA conditions revealed that under isothermal amplification, this method is robust, sensitive, and specific to a diverse panel of clinical and environmental Sporothrix strains.

Materials and methods

Sporothrix strains and culture conditions

A total of 96 reference Sporothrix strains obtained from the Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil were used for RCA testing, including clinical and environmental isolates (Table 1). These isolates were previously characterized down to the species level via phylogenetic analysis of the calmodulin-encoding gene (CAL) and the rDNA operon (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2), as described elsewhere (Madrid et al., 2010; Silva-Vergara et al., 2012; Rodrigues et al., 2013a,b, 2014b,d; Sasaki et al., 2014). Isolates originated mainly from different regions of Latin America and covered a broad range haplotypes (Rodrigues et al., 2014d), drug sensitivities (Rodrigues et al., 2014c), and clinical manifestations, including the fixed, lymphocutaneous, and disseminated forms of sporotrichosis (Rodrigues et al., 2014d). Cultures were stored as slants on Sabouraud Dextrose agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) at room temperature. Type strains representing the main species were included in all experiments. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics in Research Committee (Federal University of São Paulo) under protocol number 0244/11.

Table 1.

Strains, species, origin, and GenBank accession numbers of Sporothrix species used in this study.

| Isolate code | CBS code | Species | Source | Origin | GenBank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAL | ITS | |||||

| Ss05 | CBS 132985 | S. brasiliensis | Feline | Brazil | KC693830 | KF961142 |

| Ss07 | CBS 132986 | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693831 | KF961143 |

| Ss12 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693835 | KF961144 |

| Ss14 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF943632 | KF961145 |

| Ss33 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF943637 | KF961146 |

| Ss34 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF943638 | KF961147 |

| Ss37 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF943639 | KF961148 |

| Ss38 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693844 | KF961149 |

| Ss43 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | JX077112 | KF961150 |

| Ss44 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF943641 | KF961151 |

| Ss52 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693845 | KF574444 |

| Ss54 | CBS 132990 | S. brasiliensis | Feline | Brazil | JQ041903 | JN885580 |

| Ss55 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693847 | KF961152 |

| Ss56 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693848 | KF961153 |

| Ss57 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF943645 | KF961154 |

| Ss62 | CBS 132991 | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | JX077113 | KF961120 |

| Ss69 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693849 | KF961122 |

| Ss82 | CBS 132992 | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693857 | KF961125 |

| Ss87 | CBS 132993 | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693858 | KF961126 |

| Ss99 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF574460 | KF574442 |

| Ss104 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KF574461 | KF574443 |

| Ss128 | – | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | KC693861 | KF961155 |

| Ss265 | CBS 133020 | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | JN204360 | KF574445 |

| ATCC 4823G | CBS 132021 | S. brasiliensis | Feline | Brazil | KF574459 | JQ070114 |

| IPEC16490T | CBS 120339T | S. brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | AM116899 | KF574440 |

| CBS 101570 | CBS 101570 | S. brunneoviolacea | Endophyte | USA | KP017101 | KC113235 |

| Ss469T | CBS 139891 | S. chilensis | Human | Chile | KP711815 | KP711811 |

| Ss470 | CBS 139890 | S. chilensis | Soil | Chile | KP711816 | KP711812 |

| Ss06 | CBS 132922 | S. globosa | Human | Brazil | JF811336 | JN885574 |

| Ss41 | CBS 132923 | S. globosa | Human | Brazil | JF811337 | KF574456 |

| Ss49 | CBS 132924 | S. globosa | Human | Brazil | JF811338 | KF961180 |

| Ss236 | CBS 132925 | S. globosa | Human | Brazil | KC693877 | KF961181 |

| FMR 8600T | CBS 120340 | S. globosa | Human | Spain | AM116908 | FN549905 |

| FMR 9280T | CBS 937.72 | S. luriei | Human | South Africa | AM747302 | AB128012 |

| Ss132 | CBS 132927 | S. mexicana | Human | Brazil | JF811340 | KF574457 |

| Ss133 | CBS 132928 | S. mexicana | Human | Brazil | JF811341 | KF961182 |

| FMR 9107 | CBS 120342 | S. mexicana | Vegetal | Mexico | AM398392 | – |

| FMR 9108LT | CBS 120341 | S. mexicana | Soil | Mexico | AM398393 | FN549906 |

| FMR 8939T | CBS 302.73 | S. pallida | Soil | UK | AM398396 | – |

| Ss327 | – | S. pallida | Feline | Brazil | KF574471 | KF574458 |

| CBS 111110 | CBS 111110 | S. pallida | Insect | Germany | AM398382 | – |

| Ss03 | CBS 132963 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JX077117 | KF574446 |

| Ss04 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JX077118 | KF961156 |

| Ss13 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KC693836 | KF961157 |

| Ss15 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KC693837 | KF961158 |

| Ss16 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JQ041898 | KF961159 |

| Ss17 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KC693838 | KF961160 |

| Ss19 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943633 | KF961161 |

| Ss22 | CBS 132964 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943634 | KF961162 |

| Ss36 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KC693843 | KF961163 |

| Ss39 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JQ041899 | JN885576 |

| Ss40 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JQ041900 | JN885577 |

| Ss42 | CBS 132966 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943640 | KF961164 |

| Ss45 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KJ020358 | KF961165 |

| Ss46 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943642 | KF961166 |

| Ss47 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JQ041901 | KF961118 |

| Ss48 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943643 | KF961167 |

| Ss58 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943646 | KF961119 |

| Ss59 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943647 | KF961168 |

| Ss61 | – | S. schenckii | Soil | Brazil | KF561244 | KF574447 |

| Ss63 | CBS 132968 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JX077123 | KF961121 |

| Ss64 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JX077124 | KF961169 |

| Ss73 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KC693853 | KF961170 |

| Ss75 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KC693854 | KF961123 |

| Ss78 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KC693855 | KF961171 |

| Ss80 | CBS 132969 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JX077125 | KF961124 |

| Ss102 | CBS 132970 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943671 | KF961172 |

| Ss105 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943673 | KF961127 |

| Ss107 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943675 | KF961128 |

| Ss109 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943676 | KF961129 |

| Ss110 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943677 | KF961173 |

| Ss113 | CBS 132972 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943679 | KF961130 |

| Ss116 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943680 | KF961131 |

| Ss118 | CBS 132974 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JX077126 | KF961174 |

| Ss119 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943682 | KF961175 |

| Ss122 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943685 | KF961132 |

| Ss123 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943686 | KF961133 |

| Ss124 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943687 | KF961176 |

| Ss126 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JQ041904 | JN885581 |

| Ss129 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943689 | KF961134 |

| Ss130 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943690 | KF961135 |

| Ss136 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943692 | KF961177 |

| Ss137 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF574462 | KF574448 |

| Ss138 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943693 | KF961136 |

| Ss140 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF574463 | KF574449 |

| Ss141 | CBS 132975 | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JQ041905 | JN885582 |

| Ss143 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | JQ041906 | JN885583 |

| Ss144 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943695 | KF961178 |

| Ss158 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943698 | KF961137 |

| Ss190 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943701 | KF961138 |

| Ss240 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Brazil | KF943704 | KF961141 |

| Ss159 | CBS 132976 | S. schenckii | Human | Japan | KF574464 | KF574450 |

| Ss160 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Mexico | KF574465 | KF574451 |

| Ss161 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Mexico | KF574466 | KF574452 |

| Ss162 | CBS 132977 | S. schenckii | Vegetal | Mexico | KF574467 | KF574453 |

| Ss163 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Peru | KF574468 | KF574454 |

| Ss164 | – | S. schenckii | Human | Peru | KF574469 | KF574455 |

| ATCC 4821G | CBS 132984 | S. schenckii | Human | USA | KF574470 | JQ070112 |

| CBS 359.36T | CBS 359.36 | S. schenckii | Human | USA | AM117437 | FJ545232 |

| FMR 9338T | CBS 124561 | S. brunneoviolacea | Soil | Spain | KF574472 | FN546959 |

| FMR 8977 | CBS 125442 | S. dimorphospora | Soil | Spain | FN546961 | – |

| C8213 | – | Ophiostoma stenoceras | Human | Venezuela | KF478913 | KJ999893 |

| Pb18 | – | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | Human | Brazil | – | – |

| 832 | – | Histoplasma capsulatum | Human | Brazil | – | – |

| CBS 2530 | CBS 2530 | Trichosporon asahii | Human | Brazil | – | – |

| ATCC 10231 | CBS 6431 | Candida albicans | Human | Unknown | – | – |

| CBS 10079 | CBS 10079 | Cryptococcus neoformans | Human | Australia | – | – |

IPEC, Instituto de Pesquisa Clínica Evandro Chagas, Fiocruz, Brazil; FMR, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Reus, Spain; CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, USA; NK, not known;

, type strain;

, genome. All “Ss” strains belong to the culture collection of Federal University of SP (UNIFESP).

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted and purified directly from fungal colonies with the FastDNA Kit (MP Biomedicals, Vista, CA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 10-day old colonies were transferred to screw-cap tubes containing ceramic beads 0.25″ in diameter plus matrix A and 1 mL CLS-Y. Suspensions were homogenized three times in a Precellys 24-Dual homogenizer (Bertin Technologies, France) at 6000 rpm for 20 s with 15-s intervals. DNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), based on the default value [1 optical density (OD) unit = 50 mg/mL double-stranded DNA]; thereafter, DNA was diluted to a final concentration of 100 ng/μL. DNA quality was evaluated by determining ODs at wavelengths of 260 and 280 nm, and calculating the OD260∕280 ratio; only samples with OD260∕280 = 1.8−2.0 were used in further analyses. DNA samples were stored at −20°C until use in PCR. The quality of the extracted DNA was assessed by amplification of part of the rDNA operon using the universal primers ITS1 (5′-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT TGC GG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3′) (White et al., 1990). Amplified products were separated via agarose gel electrophoresis. Amplification of a single product indicated that the sample was free of PCR inhibitors.

Primer design and PCRs

CAL sequences from 277 isolates belonging to the S. schenckii complex, (Rodrigues et al., 2014d) allied species and genera (Ophiostoma and Grosmannia), and other pathogens were included in order to develop new primers targeting exons 3–5 of CAL. These sequences were previously deposited online at GenBank and described by Marimon et al. (2006, 2007, 2008a); Rodrigues et al. (2013a,b, 2014b,d, 2015a), Fernandes et al. (2013), and Sasaki et al. (2014). Nucleotide sequences were aligned using MAFFT v.7 (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The CAL alignment was corrected manually using MEGA 6 (Tamura et al., 2013) in order to avoid mispaired bases. Primer3 (http://primer3.wi.mit.edu/) (Untergasser et al., 2012) was used to evaluate melting temperature, %GC content, dimers, and mismatches in candidate sequences. Candidate primer pairs were evaluated with Mfold (Zuker, 2003) for potential secondary structures that would reduce the efficiency of amplification. The specificity of the new CAL primer pair was further validated in silico with Primer-BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) (Ye et al., 2012).

Sporothrix total DNA was directly used as template in PCRs with the new CAL primer pair. Reactions were performed in a final volume of 12.5 μL, including 6.25 μL PCR Master Mix buffer (2 ×; 3 mM MgCl2, 400 mM each dNTP, and 50 U/mL Taq polymerase; Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 4.25 μL water, 0.5 μL forward primer CAL-Fw (5′-CGC AAT GCC AGG CCG AGT CAC-3′; 10 pmol/μL), 0.5 μL reverse primer CAL-Rv (5′-ATT TCT GCA TCA TGA GCT GGA C-3′; 10 pmol/μL), and 1 μL target DNA (100 ng/μL). PCRs were performed in an Eppendorf Mastercycler Pro (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). PCR conditions consisted of an initial step of 95°C for 4 min followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C, as well as a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. Aliquots (3 μL) of the PCR products were analyzed on a 1.2% agarose gel (100 V, 60 min) in the presence of GelRed™ (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) and photographed under ultraviolet illumination using the L-Pix Touch (Loccus Biotecnologia, São Paulo, Brazil) imaging system (Rodrigues et al., 2015b).

Phylogenetic analysis

Amplified products were gel-purified with the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. DNA samples were sequenced with an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer 48-well capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the DYEnamic ET Dye Terminator Kit with Thermo Sequenase II DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems). Fragments were sequenced on both strands to increase the quality of sequence data (Phred > 30) and assembled into consensus sequences using CAP3 (Hall, 1999). Consensus sequences were used for BLAST.

Genetic relationships were investigated via phylogenetic analysis using neighbor-joining-, maximum likelihood-, and maximum parsimony-based methods. Phylogenetic trees based on a combined dataset (CAL + rDNA operon) were constructed in MEGA6 (Tamura et al., 2013). Evolutionary distances were computed using Kimura's two-parameter model (Kimura, 1980), and the robustness of branches was assessed by bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1985).

Padlock probe design

Padlock probes were designed based on the dataset described above. All CAL haplotypes previously described by our group (Fernandes et al., 2013; Rodrigues et al., 2013a,b, 2014b,d; Sasaki et al., 2014) were aligned using MAFFT v.7 and screened for informative nucleotide polymorphisms that were conserved within a single species and divergent between species. Type strains were included for all Sporothrix species evaluated.

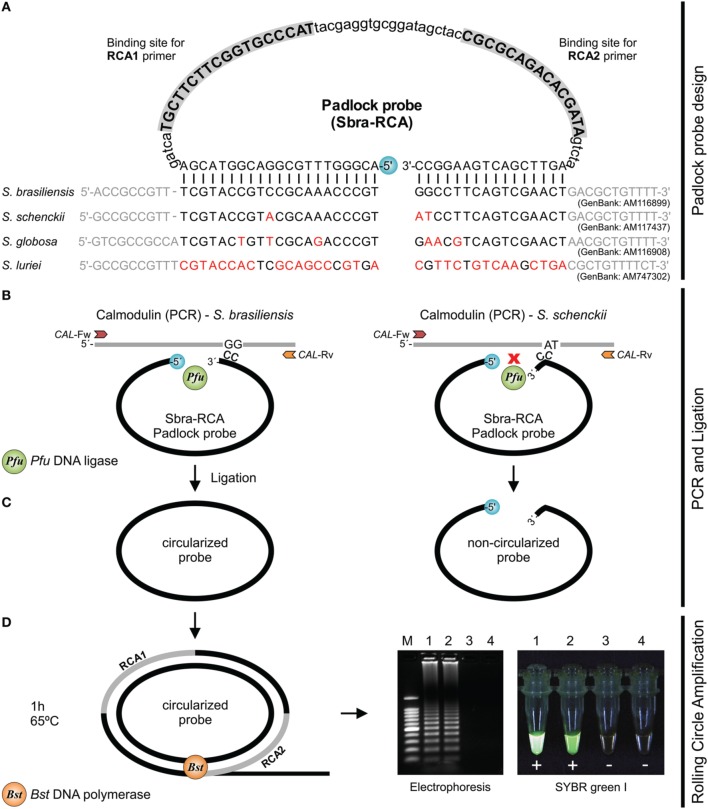

Six species-specific padlock probes were designed. Primer3 was used to evaluate melting temperature, %GC content, dimers, and mismatches in candidate padlock probes. To enhance specific binding, the 5′ end probe-binding arm was constructed with minimal secondary structure (evaluated in Mfold) and a melting temperature of 66~70°C. The ligation temperature was set to 63°C. To increase specificity, target-complementary sites were chosen at the 3′ end probe-binding arm with a melting temperature of 48–53°C (Najafzadeh et al., 2011; Lackner et al., 2012). The schematic of the RCA method is shown in Figure 1. Padlock probes were synthesized at Integrated DNA Technologies (USA) using Ultramer DNA Oligo technology at a final scale of 4 nmol. The 5′-terminal end of the padlock probes was phosphorylated (Figure 1). In silico specificity of the 5′ and 3′ end probe-binding arms were verified against sequences from Sporothrix, including the type strains.

Figure 1.

Schematic of RCA of circularized padlock probes. (A) S. brasiliensis (Sbra-RCA) padlock probe design. (B) CAL is amplified by PCR with primers CAL-Fw and CAL-Rv; PCR products are submitted to ligation. Circularization of padlock probes occurs only if both probe arms hybridize correctly to the target sequence. (C) Upon specific hybridization, the phosphorylated 5′ end and the free hydroxyl at the 3′ end of the probe are joined by Pfu DNA ligase. After ligation, non-circularized probes and single-stranded primers are removed with Exo I and Exo III (optional step). (D) Circularized padlock probes serve as DNA template and signal amplification occurs via RCA, using Bst DNA polymerase and the primers RCA1 and RCA2. DNA synthesis occurs continuously for 1 h under isothermal amplification (65°C). DNA products are detected by gel electrophoresis or directly with SYBR Green I.

Ligation

Ligation reactions were performed in a final volume of 10 μL, including 1 μL purified CAL amplicon (2–5 pmol/μL) mixed with 0.1 μL Pfu DNA ligase (4 U/μL; Agilent Technologies, USA), 2 μL padlock probe (0.1 μM; Integrated DNA Technologies), 1 μL 10 × buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL, 0.01 mM rATP, and 1 mM dithiothreitol; Agilent Technologies), and 5.9 μL ultra-pure water. A reaction containing all these components except the CAL amplicon served as the negative control. Ligation started with 5 min of pre-denaturation at 94°C, followed by five cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 4 min at 63°C. Normally, RCA can be performed with one denaturation cycle followed by one ligation cycle, but we used five cycles in order to improve the yield of RCA products (Kong et al., 2008).

Exonucleolysis

Non-circularized padlock probes and excess primers were removed after ligation via endonuclease digestion at 37°C in a final volume of 20 μL. The exonucleolysis mix consisted of 0.5 μL Exo I (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), 1 μL 10 × Exo I Buffer (New England BioLabs), 0.2 μL Exo III (New England BioLabs), 1 μL 10 × Exo III Buffer (New England BioLabs), and 7.3 μL ultra-pure water. The exonucleolysis mix (10 μL) was then directly mixed with 10 μL of the ligation reaction and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Enzyme activity was stopped via incubation at 94°C for 3 min.

RCA

RCAs were run in duplicate in total volumes of 25 μL with 3 μL of enzyme-treated ligation product as template. The RCA mix contained 4 U Bst DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs), 2.5 μL 10 × Bst Thermopol reaction buffer (containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 0.1% Triton X-100; New England BioLabs), 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix (Promega), 0.5 μL RCA1 primer (10 μM; Integrated DNA Technologies, USA), and 0.5 μL RCA2 primer (10 μM; Integrated DNA Technologies, USA). RCAs were incubated for 60 min at 65°C. A negative control reaction contained all RCA components except enzyme-treated ligation product as template. Aliquots (10 μL) of the reactions were resolved on 1.2% (w/v) agarose gels for 60 min at 100 V in the presence of GelRed™. We included a lane loaded with GeneRuler 100 bp Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Bands were visualized using the L-Pix Touch imaging system. For direct visual detection of replicated DNA in the RCA reactions, 1 μL 10-fold diluted (original 10,000 ×) SYBR Green I (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to the reaction tubes and imaged under ultraviolet illumination using the L-Pix Touch imaging system.

Sensitivity and detection limit

CAL amplicons were purified with the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. CAL concentration was determined with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer as described above; thereafter, CAL DNA was diluted to a final concentration of 300 ng/μL. Copy numbers were calculated with an online tool based on Avogadro's number (http://cels.uri.edu/gsc/cndna.html; accessed in May 1, 2015). For calculation, an amplicon length of 850 bp was assumed. We evaluated the sensitivity of each padlock probe to ensure reliable amplification at low levels of target DNA. We performed 10-fold serial dilutions of CAL DNA, starting with 3 × 1011 copies per tube and ending with 3 copies per tube. The detection limit was noted for each padlock probe.

Specificity of padlock probes

Padlock-probe specificity was determined using CAL amplicons from closely related Sporothrix species. Each probe was tested in vitro against several non-target CAL sequences belonging to clinical (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) and environmental (S. mexicana and S. pallida) species. In addition, we used several sequences from other medically relevant fungi, including agents of superficial, subcutaneous, and systemic mycosis in humans and animals. RCA conditions and gel electrophoresis were as described above.

Statistical analysis

To measure the degree of concordance of the results from RCA and phylogeny-based classification (CAL+ITS) (Rodrigues et al., 2014d) or RCA and species-specific PCR (Rodrigues et al., 2015b), we calculated the kappa statistic and its 95% confidence interval. Kappa values were interpreted as follows: 0.00–0.20, poor agreement; 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80, good agreement; 0.81–1.00, very good agreement (Altman, 1991). All calculations were performed with MedCalc Statistical Software version 14.8.1 (MedCalc Software bvba; http://www.medcalc.org).

Detection of Sporothrix DNA from other sources

To demonstrate the feasibility of our RCA approach for sensitive and sequence-specific detection of Sporothrix DNA within a complex mixture containing vegetable/host nucleic acids, we used artificially contaminated (spiked) environmental and animal samples. Sporothrix brasiliensis (CBS 132990), S. schenckii (CBS 359.36), S. globosa (CBS 120340), S. luriei (CBS 937.72), S. mexicana (CBS 120341), and S. pallida (CBS 302.73) were cultured on potato dextrose agar plates (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) at room temperature for 7 days to promote conidiation. For environmental detection, a conidial suspension was prepared with sterile saline solution and adjusting the OD 520 nm to 0.2, which approximately corresponds to a concentration of 106 cells mL−1. Thereafter, a total of 50 μL of each dilution of the conidial suspension was added to screw cap tubes (as described in 2.2 DNA extraction) and co-extracted with soil (100 mg), Sphagnum moss (50 mg) or rose leaves (Rosa spp., 50 mg), corresponding the main sources of Sporothrix in nature reported in the literature (Rodrigues et al., 2014a). DNA extraction procedures were the same as described above except that for environmental samples, instead of CLS-Y, we used 800 μL of the CLS-VF plus 200 μL of the PPS solutions from Fast DNA kit (MP Biomedicals, Vista, CA, USA). Negative control included non-spiked environmental samples. As a quality control, all samples (spiked and non-spiked) were also tested by PCR using species-specific primers as described elsewhere (Rodrigues et al., 2015b) to discharge any prior contamination with Sporothrix DNA as well as to check the presence of PCR inhibitors, which are often co-extracted with soil or plants. In doing so, we evaluated both, the presence of Sporothrix DNA (before spike) and the absence of PCR inhibitors (after spike).

For detection from host samples, we used DNA from non-infected BALB/c mice (Rodrigues et al., 2015b). Briefly, fresh tissue fragments (~100 mg) from the spleen, lungs, tail and feces were placed into screw cap tubes containing a 0.25″ in diameter plus matrix A and 1 mL CLS-TS (MP Biomedicals, Vista, CA, USA). Tissue DNA were extracted as described elsewhere (Rodrigues et al., 2015b). Animal DNA quality was assessed by amplifying the β-actin gene in the BALB/c genome as described by Pahl et al. (1999). Samples that generated positive amplification signals were regarded to be free of PCR inhibitors. DNA extracted from tissue samples (diluted at 100 ng/μl) were spiked with 100 ng of a single Sporothrix spp. DNA (10:1). This study was performed in strict accordance with recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Afterwards, for both environmental and clinical samples (spiked and non-spiked), 1 μl was taken and directly used as templates in PCR reactions with the primers CAL-Fw and CAL-Rv as described above (see Section Primer design and PCRs). Thereafter, 1 μL of amplicons were submitted to ligation (see Section Ligation), exonucleolysis (see Section Exonucleolysis), and RCA (see Section RCA). As a positive control we included a reaction containing CAL amplicon as a target for each specific probe. A negative control reaction contained all RCA components except enzyme-treated ligation product as template (blank).

Results

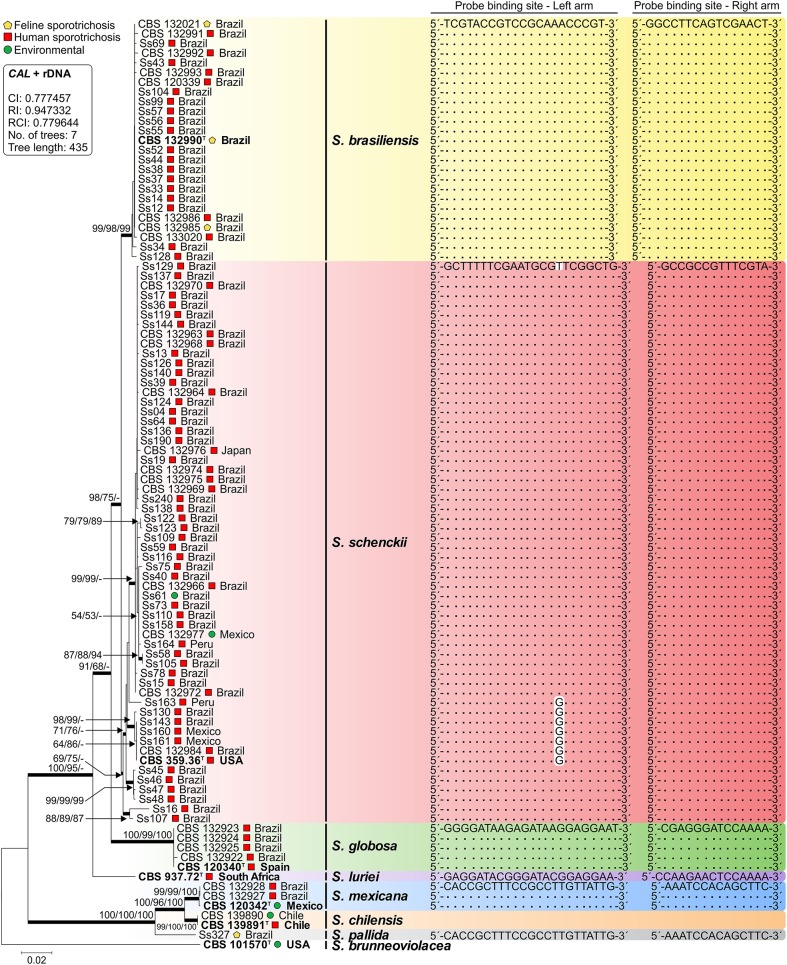

Isolates used to develop and validate RCA were previously identified down to the species level via DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of CAL and the rDNA ITS region (Rodrigues et al., 2014d). The final dataset had 1359 characters, of which 450 were variable, 280 were parsimony-informative, and 169 were singleton. Sequences from a genetically diverse panel of Sporothrix isolates clustered into eight groups with high bootstrap support, matching the species previously described in the literature (Figure 2). In silico analyses of the 5′ and 3′ end probe-binding arms revealed that RCA probes were conserved within a single species (Figure 2). In addition, the sequence homology of each CAL primer as well as RCA probes sequences were assessed with Primer-BLAST, and no significant homology was found with human, plant, mouse, or microorganism sequences outside the genus of Sporothrix.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree generated by neighbor joining, maximum likelihood, and maximum parsimony using partial nucleotide sequences of CAL and the rDNA operon (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2). Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) were added (denoted as neighbor joining/maximum likelihood/maximum parsimony). Bar, total nucleotide differences between taxa; T = type strain. The box contains statistics from maximum parsimony: CI, consistency index; RI, retention index; RCI, composite index (for all sites). Sequence conservation through a genetically diverse panel of Sporothrix for both left and right arms of each padlock probe is indicated. Further information about isolate sources appears in Table 1.

Compared to other markers (e.g., β-tubulin, translation elongation factor 1α, the rDNA operon, and chitin synthase (Marimon et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2015), the CAL region offers a substantial number of interspecific variations (205 parsimony-informative sites for CAL vs. 75 in the rDNA) that supports the use of CAL to discriminate closely related Sporothrix (Table 1). Such variation led us to choose CAL to develop six padlock probes targeting species-specific regions of human-pathogenic Sporothrix species (Table 2). Probes were applied in vitro during isothermal RCA to identify 25 S. brasiliensis, 58 S. schenckii s. str., 5 S. globosa, 1 S. luriei, 4 S. mexicana, and 3 S. pallida samples. Typically, each padlock probe was hybridized to a CAL target (~850 bp) to form a circular probe by Pfu DNA ligase when there was a perfect probe-template match. Circularized probes were amplified with replication primers RCA1 and RCA2 with Bst DNA polymerase. Amplification was achieved for all species evaluated in the conditions described.

Table 2.

Details of species-specific sites and padlock probes targeting CAL in Sporothrix spp.

| Organism target | Padlock probe/primer | Probes and primers sequences |

|---|---|---|

| S. brasiliensis | Sbra-RCA | 5′-P-ACGGGTTTGCGGACGGTACGAGatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCAT tacgaggtgcggatagctacCGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaAGTTCGACTGAAGGCC-3′ |

| S. schenckii | Ssch-RCA | 5′-P-CAGCCGAMCGCATTCGAAAAAGCGatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCAT tacgaggtgcggatagctacCGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaTACGAAACGGCGGC-3′ |

| S. globosa | Sglo-RCA | 5′-P-ATTCCTCCTTATCTCTTATCCCCGatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCAT tacgaggtgcggatagctacCGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaTTTTGGATCCCTCG-3′ |

| S. luriei | Slur-RCA | 5′-P-TTCCTCCGTATCCCGTATCCTCGatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCAT tacgaggtgcggatagctacCGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaTTTTGGAGTTCTTGG-3′ |

| S. mexicana | Smex-RCA | 5′-P-CAATAACAAGGCGGAAAGCGGTGGatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCAT tacgaggtgcggatagctacCGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaGAAGCTGTGGATTT-3′ |

| S. pallida | Spa-RCA | 5′-P-CGCGAAAATGGCGGAAAGCAGCGatcaTGCTTCTTCGGTGCCCAT tacgaggtgcggatagctacCGCGCAGACACGATAgtctaGAGTTTCCAAGCAC-3′ |

| RCA1 | 5′-ATG GGC ACC GAA GAA GCA-3′ | |

| RCA2 | 5′-CGC GCA GAC ACG ATA-3′ | |

| CAL-Fw | 5′-CGC AAT GCC AGG CCG AGT CAC-3′ | |

| CAL-Rv | 5′-ATT TCT GCA TCA TGA GCT GGA C-3′ |

5′-P: The 5′ terminal end of padlock probe P was phosphorylated.

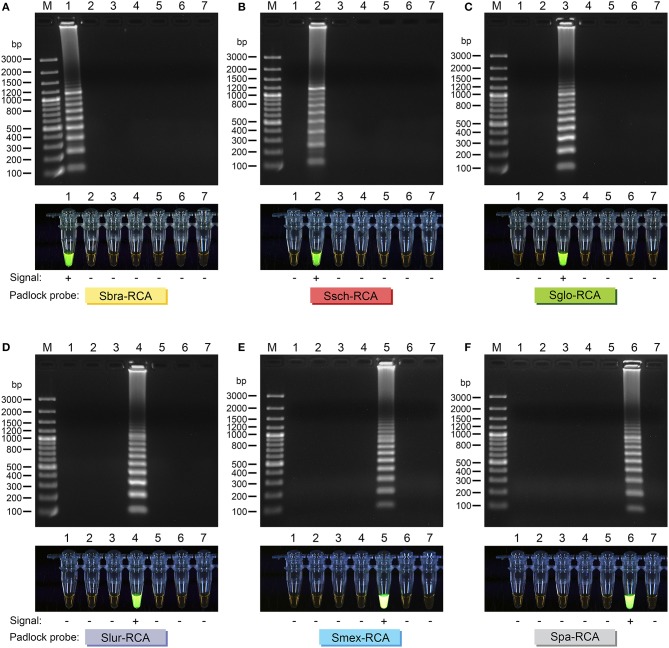

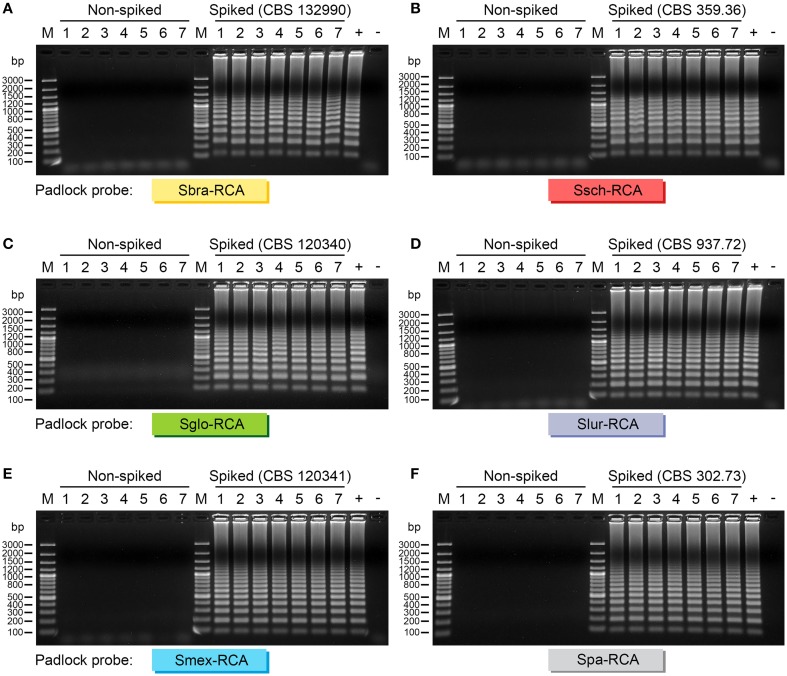

RCA signal for the tested strains was easily visualized on 1.2% agarose gels. Interpretation of the RCA is straightforward and is based on a simple positive or negative result. Positive RCA generated a typical ladder-like pattern of fragments increasing in size, comprising the monomer and multimer repeats of the amplified product formed by single and multiple copying of the circularized padlock probe, while negative reactions had a clean background (Figure 3). RCA success was also determined by adding SYBR Green I dye after reactions; positive reactions fluoresced intensely, while negative reactions lacked fluorescence (Figure 3). The results from analysis with SYBR Green I dye were compatible with those obtained with electrophoresis (Figure 3). RCA-based identification completely matched (100%) identification via phylogenetic analysis (kappa 1.0; 95% confidence interval 1.0-1.0; Supplementary Table 1) and species-specific PCR (Rodrigues et al., 2015b) (kappa 1.0; 95% confidence interval 1.0-1.0; Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of successful RCA of (A) Sbra-RCA padlock probe; (B) Ssch-RCA padlock probe; (C) Sglo-RCA padlock probe; (D) Slur-RCA padlock probe; (E) Smex-RCA padlock probe; and (F) Spa-RCA padlock probe. Gel lanes: 1, S. brasiliensis (CBS 132990); 2, S. schenckii (CBS 359.36); 3, S. globosa (CBS 120340); 4, S. luriei (CBS 937.72); 5, S. mexicana (CBS 120341); 6, S. pallida (CBS 302.73); 7, negative control. Amplicons were sized by comparison with bands of known size from the GeneRuler 100 bp Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Direct visual detection of replicated DNA in RCA reactions with SYBR Green I (lower lanes). Tubes were imaged under ultraviolet light. Tube lanes: 1, S. brasiliensis (CBS 132990); 2, S. schenckii (CBS 359.36); 3, S. globosa (CBS 120340); 4, S. luriei (CBS 937.72); 5, S. mexicana (CBS 120341); 6, S. pallida (CBS 302.73); 7, negative control. Each padlock probe is specified.

The specificity of the identification assay was first determined for a subset of 40 Sporothrix isolates. Fifteen S. schenckii isolates belonging to different CAL haplotypes (Rodrigues et al., 2014d) were tested against species-specific padlock probes to evaluate the false-positive rate of the assay. No cross reactivity in vitro was apparent between closely related species, and all padlock probes yielded 100% specificity. Secondly, specificity of the identification was evaluated against other pathogenic or non-pathogenic fungi, and probes failed to replicate DNA from Sporothrix brunneoviolacea, Sporothrix dimorphospora, Ophiostoma stenoceras, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Trichosporon asahii, Candida albicans, and Cryptococcus neoformans (Supplementary Figure 1). Judging from in vitro results, our data supports the high specificity of the six padlock probes which was in good concordance with the results obtained via in silico predictions using BLASTn-search analyses.

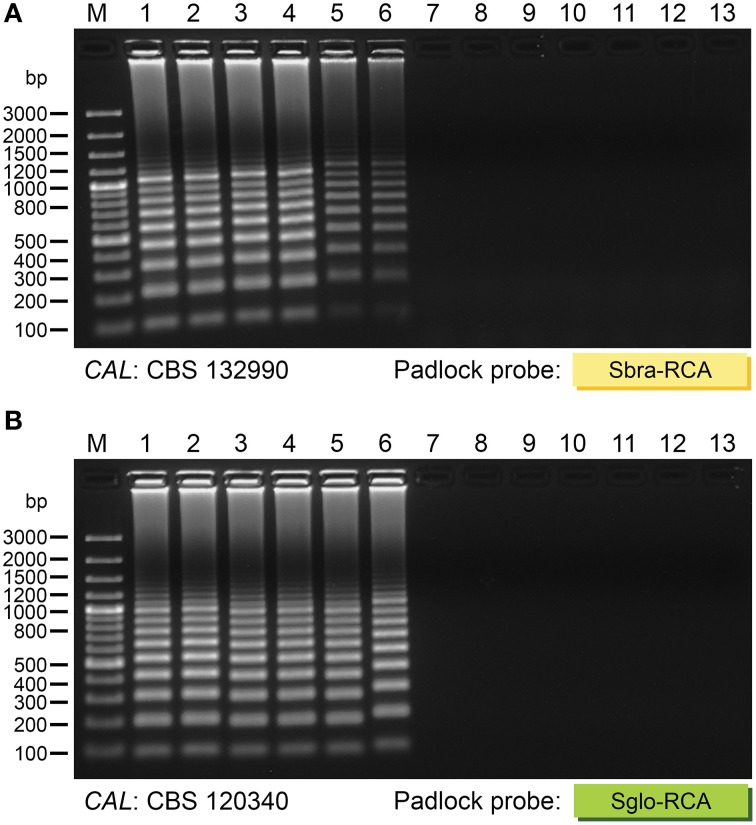

The sensitivity of each probe was tested for the CAL sequence from a reference type strain of each species. CAL DNA was quantified and 10-fold diluted in ultra-pure water to achieve amplicon concentrations ranging from 3 × 1011 copies per tube to three copies per tube. RCA of these dilutions indicated excellent sensitivity, since all probes were detectable down to 3 × 106 copies with equal reliability after electrophoresis (representative gels in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative agarose gel electrophoresis of the analytical sensitivity of RCA. Species-specific padlock probes were used for RCA of 10-fold dilutions of CAL amplicon from (A) S. brasiliensis (CBS 132990) and (B) S. globosa (CBS 120340). The in-gel detection limit was 3 × 106 copies of CAL for all probes. Gel lanes: 1, 3 × 1011 copies; 2, 3 × 1010 copies; 3, 3 × 109 copies; 4, 3 × 108 copies; 5, 3 × 107 copies; 6, 3 × 106 copies; 7, 3 × 105 copies; 8, 3 × 104 copies; 9, 3 × 103 copies; 10, 300 copies; 11, 30 copies; 12, 3 copies; 13, negative control. Marker (M): GeneRuler 100 bp Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Furthermore, we evaluated if padlock probes could selectively detect Sporothrix DNA from complex environmental and animal samples. Spiked samples were used to determine whether DNA detection was affected by the presence of different mixtures of the biological samples, what is essential for validating and assessing the accuracy of RCA in detecting pathogen-specific DNA. Judging from both environmental and clinical samples, we successfully detected positive RCA signals as a typical ladder-like pattern from soil, Sphagnum moss, Rose spp., spleen, lungs, tail, and feces of mouse spiked with Sporothrix DNA. No false positives were detected in samples from the control group (non-spiked samples), which remained as a clean background. It can thus be assumed that the padlock probes can selectively replicate pathogen DNA, confirming the high specificity of our RCA-based assay as well as its potential applicability to detection studies (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of successful RCA amplification of members of Sporothrix schenckii-Ophiostoma stenoceras complex from a sample containing host/vegetable and fungal DNA. (A) Sbra-RCA padlock probe; (B) Ssch-RCA padlock probe; (C) Sglo-RCA padlock probe; (D) Slur-RCA padlock probe; (E) Smex-RCA padlock probe; and (F) Spa-RCA padlock probe. Gel lanes 1–7 on the left correspond to non-spiked samples (negative control): 1, soil; 2, Sphagnum moss; 3, Rose spp.; 4, BALB/c spleen; 5, BALB/c lungs; 6, BALB/c tail; 7, BALB/c feces. Gel lanes 1–7 on the right correspond to spiked samples (species as indicated): 1, spiked soil; 2, spiked Sphagnum moss; 3, spiked Rose spp.; 4, spiked BALB/c spleen; 5, spiked BALB/c lungs; 6, spiked BALB/c tail; 7, spiked BALB/c feces. +, positive control using DNA from culture; -, negative control (blank). Amplicons were sized by comparison with bands of known size from the GeneRuler 100 bp Plus DNA Ladder (M) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The results show an efficient replication of samples spiked with pathogen DNA. On the other hand, RCA failed to replicate the DNA originated solely from environmental or clinical samples (non-spiked), which remained negative. It can thus be assumed that the padlock probes can selectively replicate pathogen DNA, confirming the high specificity of our RCA-based assay.

Discussion

The search for techniques that avoid variability and lower costs for identifying pathogenic Sporothrix species motivated us to develop and evaluate an RCA-based assay for this application. RCA is a powerful method for the molecular characterization of medically important fungi (Najafzadeh et al., 2011, 2013; Sun et al., 2011; Davari et al., 2012; Lackner et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2013; Hamzehei et al., 2013). Here, we report the successful use of six species-specific padlock probes for fast, robust, and accurate diagnosis of sporotrichosis.

We redesigned the primer pair targeting the CAL gene in order to increase the sensitivity and specificity of PCR amplification. Degenerate primers that target CAL (CL1 and CL2A, O'Donnell et al., 2000) are associated with varying sensitivity and success of amplification depending on the species assayed (Zhang et al., 2015). The new primers developed here (CAL-Fw and CAL-Rv) are directly applicable to molecular phylogeny studies of Sporothrix/Ophiostoma species. Successful amplification was confirmed with 96 DNA samples mainly derived from Sporothrix isolates recovered from clinical cases in Latin America and other regions of the world (Table 1). The species successfully amplified by PCR included S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii s. str., S. globosa, S. luriei, S. mexicana, S. pallida, S. chilensis, S. brunneoviolaceae, and S. dimorphospora. Although the use of degenerate primers CL1 and CL2A increases the flexibility of PCR, low amounts of amplicon are usually recovered for S. luriei (Rodrigues et al., 2014b), S. schenckii, S. globosa, and especially for isolates embedded in the environmental clade (Zhang et al., 2015). Therefore, we propose a new primer combination (CAL-Fw and CAL-Rv) that covers the region amplified using the CL1 and CL2A primers (exons 3–5) but generates slightly longer amplicons and higher-quality sequences.

We also designed and tested padlock probes to identify polymorphic sequences produced by PCR of CAL. After ligation, we removed nucleotides from single-stranded DNA (non-circularized padlock probes and excess primer) with Exo I and Exo III. Although this step has been regarded as optional (Sun et al., 2011; Davari et al., 2012; Najafzadeh et al., 2013; Dolatabadi et al., 2014), we included it in order to avoid non-specific amplification during RCA. It is important to note that, similar to the results obtained by Ahmed et al. (2014) for agents of eumycetoma, exonucleolysis during Sporothrix identification may generate low RCA-positive signal on electrophoresis or with fluorescence (Supplementary Figure 2). In the current investigation, RCA driven by Bst DNA polymerase successfully replicated Sporothrix circularized padlock probes with high specificity. Gel-free systems that use intercalating fluorescent dye to visualize amplified product are particularly interesting due to the shorter amount of time necessary for accurate results. SYBR Green I dye is a quick and inexpensive reagent for assessing RCA without the routine use of electrophoresis, which is especially attractive for investigations in remote areas where sporotrichosis is endemic but where equipment for molecular diagnosis is lacking.

Here, Sporothrix RCA was sensitive. We observed a typical ladder-like pattern on gel electrophoresis with as few as 3 × 106 copies of CAL amplicon per tube. This sensitivity is similar to previous results reported for Scedosporium (Lackner et al., 2012), eumycetoma-causing agents (Ahmed et al., 2014), and the mucorales (Dolatabadi et al., 2014).

We determined that identification via Sporothrix-specific RCA was 100% in agreement with phylogenetic analysis (Rodrigues et al., 2014d), analysis with CAL-RFLPs (Rodrigues et al., 2014b), and the application of species-specific primers (Rodrigues et al., 2015b) (Supplementary Table 1). The optimal method for identifying Sporothrix may depend on sample origin (soil, plant debris, animal biopsies, or isolated culture), DNA quality, and the price and sensitivity of the molecular assay. RCA, PCR-RFLP (Rodrigues et al., 2014b), and species-specific primers (Rodrigues et al., 2015b) reliably identify Sporothrix pathogenic agents down to species level. However, CAL-RFLP (Rodrigues et al., 2014b) is not recommended for detecting Sporothrix in complex mixtures of DNA such as biopsy material or in crude environmental samples such as soil and decaying wood. On the other hand, RCA and species-specific primers (Rodrigues et al., 2015b) may perform well in these situations, with similar sensitivity, depending on sample preparation.

We demonstrated for the first time that padlock probes are useful for tracking Sporothrix in ecological studies, e.g., for monitoring the presence of Sporothrix DNA from soil and plant debris, the most common environmental sources during outbreaks. Isolation of Sporothrix spp. from soil samples is reported in endemic areas (Mehta et al., 2007; Criseo and Romeo, 2010; Montenegro et al., 2014; Govender et al., 2015), however, only a few studies performed molecular characterization of environmental isolates down to species level. Notwithstanding, the distributions of medically-relevant Sporothrix in soil and the conditions that increase its occurrence have been the subject of various hypothesis (Zhang et al., 2015). Sporothrix is embedded in the Ophiostomatales, an order that comprises many ecological niches. These microorganisms are adapted for dispersal by insects (Coleoptera: Scolytinae), are associated with the Protea, Rosa spp., Sphagnum moss or are widely distributed in the soil (De Beer and Wingfield, 2013). In this scenario, the RCA-based assay developed here is an important tool for helping to detect Sporothrix DNA directly in complex environmental samples, as a reliable alternative to DNA sequencing, expanding our knowledge on the distribution of these microorganisms in nature, especially in endemic regions.

Sporotrichosis primarily affects warm-blooded animals, particularly humans and cats. The disease is emerging as a global threat, with high incidences in somewhat warmer regions, but it still bears with it the problem of lack of early diagnosis associated with correct species identification. To evaluate the capacity of padlock probes detecting Sporothrix DNA from clinical samples of warm-blooded animals, we used DNA from BALB/c mice spiked with known Sporothrix species. All six padlock probes showed a high degree of specificity that makes them useful for detecting medically-relevant Sporothrix DNA sequences even in the presence of host DNA. Our data also shows that within host samples, the presence of Sporothrix DNA can also be explored in feces, as demonstrated earlier by species-specific PCR (Rodrigues et al., 2015b). Indeed, feces from infected animals may be valuable samples for exploring the ecological and epidemiological features of sporotrichosis, especially because it can increase the number of foci in the environment (Schubach et al., 2003; Montenegro et al., 2014). Our RCA assay may also be useful when large-scale screening of Sporothrix spp. is required, such as in Brazil, China, and South Africa where sporotrichosis is still endemic and remains a major public health problem (Zhou et al., 2014; Govender et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015).

Unambiguous identification of human-pathogenic Sporothrix spp. based on phenotypic methods is rather challenging due to overlapping morphologies among closely related species. In this scenario, these difficulties delay the response to an outbreak and/or its epidemiological surveillance. To overcome this problem, we first demonstrated in silico that padlock probes are particularly amenable to discriminate specific polymorphisms in the CAL sequence that can be used to speciate all agents embedded in the S. schenckii complex. Second, we validate in vitro the feasibility of the RCA method for sensitive and sequence-specific detection of Sporothrix DNA derive from pure cultures. Third, as a proof of concept, we used this new RCA-based approach to successfully detect Sporothrix DNA from a complex mixture containing host/vegetable nucleic acids. The technique has several advantages, including high sensitivity, high specificity, fast, easy to perform, simple to interpret, and the lack of a need for special instrumentation; which is especially desirable during epidemics, when thousands of samples must be accurately identified. A single RCA assay (including mix preparation, ligation and amplification) takes less than 3 h. These findings are likely to improve identification, diagnosis, to guide patient treatment, to improve clinical outcomes, and to tackle the spread of future outbreaks. Due to these robustness and simplicity characteristics, RCA may also be useful in low-income regions where human and animal sporotrichosis is endemic and epidemic.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

AMR is a fellow of and acknowledges financial support from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP 2011/07350-1) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (BEX 2325/11-0). This work was supported, in part, by grants from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP 2009/54024-2), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (472600/2011-7 and 472169/2012-2), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01385

References

- Ahmed S. A., Van Den Ende B. H. G. G., Fahal A. H., Van De Sande W. W. J., De Hoog G. S. (2014). Rapid identification of black grain eumycetoma causative agents using rolling circle amplification. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8:e3368. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Paes R., De Oliveira M. M., Freitas D. F., Do Valle A. C., Zancopé-Oliveira R. M., Gutierrez-Galhardo M. C. (2014). Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8:e3094. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman D. G. (1991). Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Arrillaga-Moncrieff I., Capilla J., Mayayo E., Marimon R., Mariné M., Gené J., et al. (2009). Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15, 651–655. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borba-Santos L. P., Rodrigues A. M., Gagini T. B., Fernandes G. F., Castro R., de Camargo Z. P., et al. (2015). Susceptibility of Sporothrix brasiliensis isolates to amphotericin B, azoles, and terbinafine. Med. Mycol. 53, 178–188. 10.1093/mmy/myu056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho E., León-Navarro I., Rodríguez-Brito S., Mendoza M., Niño-Vega G. A. (2015). Molecular epidemiology of human sporotrichosis in Venezuela reveals high frequency of Sporothrix globosa. BMC Infect. Dis. 15:94. 10.1186/s12879-015-0839-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti A., Bonifaz A., Gutierrez-Galhardo M. C., Mochizuki T., Li S. (2015). Global epidemiology of sporotrichosis. Med. Mycol. 53, 3–14. 10.1093/mmy/myu062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wang B., Yang W., Kong F., Li C., Sun Z., et al. (2014). Rolling circle amplification for direct detection of rpoB gene mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 1540–1548. 10.1128/JCM.00065-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criseo G., Romeo O. (2010). Ribosomal DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of environmental Sporothrix schenckii strains: comparison with clinical isolates. Mycopathologia 169, 351–358. 10.1007/s11046-010-9274-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davari M., Van Diepeningen A. D., Babai-Ahari A., Arzanlou M., Najafzadeh M. J., van der Lee T. A., et al. (2012). Rapid identification of Fusarium graminearum species complex using Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA). J. Microbiol. Methods 89, 63–70. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beer Z. W., Wingfield M. J. (2013). Emerging lineages in the Ophiostomatales, in The Ophiostomatoid Fungi: Expanding Frontiers, eds Seifert K. A., De Beer Z. W., Wingfield M. J. (Utrecht: CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre; ), 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- De Hoog G. S., Guarro J., Gené J., Figueras M. J. (2000). Atlas of Clinical Fungi. Utrecht: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. [Google Scholar]

- Dolatabadi S., Najafzadeh M. J., de Hoog G. S. (2014). Rapid screening for human-pathogenic Mucorales using rolling circle amplification. Mycoses 57, 67–72. 10.1111/myc.12245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Evolution confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791. 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng P., Klaassen C. H., Meis J. F., Najafzadeh M. J., Gerrits Van Den Ende A. H., Xi L., et al. (2013). Identification and typing of isolates of Cyphellophora and relatives by use of amplified fragment length polymorphism and rolling circle amplification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 931–937. 10.1128/JCM.02898-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes G. F., Dos Santos P. O., Rodrigues A. M., Sasaki A. A., Burger E., de Camargo Z. P. (2013). Characterization of virulence profile, protein secretion and immunogenicity of different Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto isolates compared with S. globosa and S. brasiliensis species. Virulence 4, 241–249. 10.4161/viru.23112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A., Xu S. Q. (1995). Rolling replication of short DNA circles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 4641–4645. 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govender N. P., Maphanga T. G., Zulu T. G., Patel J., Walaza S., Jacobs C., et al. (2015). An outbreak of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis among mine-workers in South Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9:e0004096. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremião I. D., Menezes R. C., Schubach T. M., Figueiredo A. B., Cavalcanti M. C., Pereira S. A. (2015). Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Med. Mycol. 53, 15–21. 10.1093/mmy/myu061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haible D., Kober S., Jeske H. (2006). Rolling circle amplification revolutionizes diagnosis and genomics of geminiviruses. J. Virol. Methods 135, 9–16. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzehei H., Yazdanparast S. A., Davoudi M. M., Khodavaisy S., Golehkheyli M., Ansari S., et al. (2013). Use of rolling circle amplification to rapidly identify species of Cladophialophora potentially causing human infection. Mycopathologia 175, 431–438. 10.1007/s11046-013-9630-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. (1980). A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120. 10.1007/BF01731581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F., Tong Z., Chen X., Sorrell T., Wang B., Wu Q., et al. (2008). Rapid identification and differentiation of Trichophyton species, based on sequence polymorphisms of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer regions, by rolling-circle amplification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 1192–1199. 10.1128/JCM.02235-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner M., Najafzadeh M. J., Sun J., Lu Q., Hoog G. S. (2012). Rapid identification of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium strains by using rolling circle amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 126–133. 10.1128/AEM.05280-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid H., Gené J., Cano J., Silvera C., Guarro J. (2010). Sporothrix brunneoviolacea and Sporothrix dimorphospora, two new members of the Ophiostoma stenoceras-Sporothrix schenckii complex. Mycologia 102, 1193–1203. 10.3852/09-320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marimon R., Cano J., Gené J., Sutton D. A., Kawasaki M., Guarro J. (2007). Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 3198–3206. 10.1128/JCM.00808-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marimon R., Gené J., Cano J., Guarro J. (2008a). Sporothrix luriei: a rare fungus from clinical origin. Med. Mycol. 46, 621–625. 10.1080/13693780801992837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marimon R., Gené J., Cano J., Trilles L., Dos Santos Lazéra M., Guarro J. (2006). Molecular phylogeny of Sporothrix schenckii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 3251–3256. 10.1128/JCM.00081-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marimon R., Serena C., Gené J., Cano J., Guarro J. (2008b). In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of five species of Sporothrix. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 732–734. 10.1128/AAC.01012-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta K. I. S., Sharma N. L., Kanga A. K., Mahajan V. K., Ranjan N. (2007). Isolation of Sporothrix schenckii from the environmental sources of cutaneous sporotrichosis patients in Himachal Pradesh, India: results of a pilot study. Mycoses 50, 496–501. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01411.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa-Arango A. C., Del Rocío Reyes-Montes M., Pérez-Mejía A., Navarro-Barranco H., Souza V., Zúñiga G., et al. (2002). Phenotyping and genotyping of Sporothrix schenckii isolates according to geographic origin and clinical form of sporotrichosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 3004–3011. 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3004-3011.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro H., Rodrigues A. M., Galvão Dias M. A., Da Silva E. A., Bernardi F., Camargo Z. P. (2014). Feline sporotrichosis due to Sporothrix brasiliensis: an emerging animal infection in São Paulo, Brazil. BMC Vet. Res. 10:269. 10.1186/s12917-014-0269-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafzadeh M. J., Dolatabadi S., Saradeghi Keisari M., Naseri A., Feng P., de Hoog G. S. (2013). Detection and identification of opportunistic Exophiala species using the rolling circle amplification of ribosomal internal transcribed spacers. J. Microbiol. Methods 94, 338–342. 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafzadeh M. J., Sun J., Vicente V. A., de Hoog G. S. (2011). Rapid identification of fungal pathogens by rolling circle amplification using Fonsecaea as a model. Mycoses 54, e577–e582. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2010.01995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell K., Nirenberg H., Aoki T., Cigelnik E. (2000). A multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 41, 61–78. 10.1007/BF02464387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M. M., Santos C., Sampaio P., Romeo O., Almeida-Paes R., Pais C., et al. (2015). Development and optimization of a new MALDI-TOF protocol for identification of the Sporothrix species complex. Res. Microbiol. 166, 102–110. 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl A., Kühlbrandt U., Brune K., Röllinghoff M., Gessner A. (1999). Quantitative detection of Borrelia burgdorferi by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 1958–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., Bagagli E., De Camargo Z. P., Bosco S. M. G. (2014a). Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto isolated from soil in an armadillo's burrow. Mycopathologia 177, 199–206. 10.1007/s11046-014-9734-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., Cruz Choappa R., Fernandes G. F., de Hoog G. S., Camargo Z. P. (2015a). Sporothrix chilensis sp. nov. (Ascomycota: Ophiostomatales), a soil-borne agent of human sporotrichosis with mild-pathogenic potential to mammals. Fungal Biol. .[Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.funbio.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., de Hoog G. S., Camargo Z. P. (2014b). Genotyping species of the Sporothrix schenckii complex by PCR-RFLP of calmodulin. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 78, 383–387. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., De Hoog G. S., de Camargo Z. P. (2015b). Molecular diagnosis of pathogenic Sporothrix species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9:e0004190. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., de Hoog G. S., de Cassia Pires D., Brihante R. S. N., da Costa Sidrim J. J., Gadelha M. F., et al. (2014c). Genetic diversity and antifungal susceptibility profiles in causative agents of sporotrichosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 14:219. 10.1186/1471-2334-14-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., de Hoog G. S., Zhang Y., Camargo Z. P. (2014d). Emerging sporotrichosis is driven by clonal and recombinant Sporothrix species. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 3, e32. 10.1038/emi.2014.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., de Hoog S., de Camargo Z. P. (2013a). Emergence of pathogenicity in the Sporothrix schenckii complex. Med. Mycol. 51, 405–412. 10.3109/13693786.2012.719648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., de Melo Teixeira M., de Hoog G. S., Schubach T. M. P., Pereira S. A., Fernandes G. F., et al. (2013b). Phylogenetic analysis reveals a high prevalence of Sporothrix brasiliensis in feline sporotrichosis outbreaks. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2281. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., Fernandes G. F., Araujo L. M., Della Terra P. P., dos Santos P. O., Pereira S. A., et al. (2015c). Proteomics-based characterization of the humoral immune response in sporotrichosis: toward discovery of potential diagnostic and vaccine antigens. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9:e0004016. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A. A., Fernandes G. F., Rodrigues A. M., Lima F. M., Marini M. M., Dos S., et al. (2014). Chromosomal polymorphism in the Sporothrix schenckii complex. PLoS ONE 9:e86819. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubach T. M., Schubach Ade O., Cuzzi-Maya T., Okamoto T., Reis R. S., Monteiro P. C., et al. (2003). Pathology of sporotrichosis in 10 cats in Rio de Janeiro. Vet. Rec. 152, 172–175. 10.1136/vr.152.6.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Vergara M. L., de Camargo Z. P., Silva P. F., Abdalla M. R., Sgarbieri R. N., Rodrigues A. M., et al. (2012). Disseminated Sporothrix brasiliensis infection with endocardial and ocular involvement in an HIV-infected patient. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86, 477–480. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Li S. S., Zhong S. X., Liu Y. Y., Yao L., Huo S. S. (2013). Report of 457 sporotrichosis cases from Jilin province, northeast China, a serious endemic region. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 27, 313–318. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Najafzadeh M. J., Zhang J., Vicente V. A., Xi L., de Hoog G. S. (2011). Molecular identification of Penicillium marneffei using rolling circle amplification. Mycoses 54, e751–e759. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira M. D. M., Rodrigues A. M., Tsui C. K. M., de Almeida L. G. P., Van Diepeningen A. D., Gerrits Van Den Ende B., et al. (2015). Asexual propagation of a virulent clone complex in human and feline outbreak of sporotrichosis. Eukaryotic Cell 14, 158–169. 10.1128/EC.00153-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A., Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B. C., Remm M., et al. (2012). Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e115. 10.1093/nar/gks596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, in PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds Innis M., Gelfand D., Shinsky J., White T. (New York, NY: Academic Press; ), 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Coulouris G., Zaretskaya I., Cutcutache I., Rozen S., Madden T. L. (2012). Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics 13:134. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. Y., Brandwein M., Hsuih T. C., Li H. (1998). Amplification of target-specific, ligation-dependent circular probe. Gene 211, 277–285. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00113-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Hagen F., Stielow B., Rodrigues A. M., Samerpitak K., Zhou X., et al. (2015). Phylogeography and evolutionary patterns in Sporothrix spanning more than 14,000 human and animal case reports. Persoonia 35, 1–20. 10.3767/003158515X687416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Kong F., Sorrell T. C., Wang H., Duan Y., Chen S. C. (2008). Practical method for detection and identification of Candida, Aspergillus, and Scedosporium spp. by use of rolling-circle amplification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 2423–2427. 10.1128/JCM.00420-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Rodrigues A. M., Feng P., Hoog G. S. (2014). Global ITS diversity in the Sporothrix schenckii complex. Fungal Divers. 66, 153–165. 10.1007/s13225-013-0220-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. (2003). Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415. 10.1093/nar/gkg595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.