Abstract

Low intensity resistance exercise (RE) with blood flow restriction (BFR) has gained attention in the literature due to the beneficial effects on functional and morphological variables, similar to those observed during traditional RE without BFR, while the effects of BFR on post-exercise hypotension remain unclear. The aim of the present study was to compare the blood pressure (BP) response of trained normotensive individuals to RE with and without BFR. In this cross-over randomized trial, eight male subjects (23.8 ± 4 years, 74 ± 3 kg, 174 ± 4 cm) completed two exercise protocols: traditional RE (3 x 10 repetitions at 70% one-repetition maximum [1-RM]) and low intensity RE (3 x 15 repetitions at 20% 1-RM) with BFR. Blood pressure measurements were performed after 15 min of seated rest (0), immediately after and 10 min, 20 min, 30 min, 40 min, 50 min and 60 min after the experimental sessions. Similar hypotensive effects for systolic BP (SBP) were observed for both protocols (P < 0.05) after exercise, with no differences between groups (P > 0.05) and no statistically significant difference for diastolic BP (P > 0.05). These results suggest that in normotensive trained individuals, both traditional RE and RE with BFR induce hypotension for SBP, which is important to prevent cardiovascular disturbances.

Keywords: blood flow restriction, resistance training, blood pressure, low intensity

INTRODUCTION

Blood pressure (BP) consists of the force that the blood exerts on vessel walls, within a given area [1], and is a result of cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance [2]. BP elevation results in hypertension, a chronic degenerative disease that cause changes in arteries and myocardium structures, associated with endothelial dysfunction and constriction or remodelling of the vascular smooth muscle, which may cause kidney collapse [3].

Hypertension affects a large part of the adult population in developed and in developing countries [4], while data from Brazil reach prevalence values of 22.7%, as shown by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) [5]. Thus, exercise is considered an effective interventional approach for the treatment of hypertension. The behaviour of BP in response to different types of exercise has been the subject of several investigations [6–9].

According to data presented by the Brazilian Society of Cardiology [10], sedentary individuals are 30% more likely to develop hypertension than active individuals. Moreover, beyond the treatment, the preventive aspect of exercise has to be considered, because young and active individuals are also liable to be affected by hypertension.

A single session of exercise can cause an acute response of BP decrease below resting values – a phenomenon known as post-exercise hypotension (PEH) [11]. Accordingly, many studies have demonstrated the hypotensive effect of resistance exercise in hypertensive populations with different body segments [12], volume and intensity [13, 14], and order of exercises [15]. However, these studies were conducted in hypertensive populations, while there is a gap of these responses in trained normotensive individuals [16].

Recently, a training technique known as “Kaatsu training” has gained attention in the literature. This technique uses low-intensity resistance exercise with blood flow restriction (BFR) (20-50% of one-repetition maximum [1RM]) with sets of 15 to 20 repetitions, and has the capacity of generating functional and morphological adjustments similar to high-intensity resistance training without BFR [17–19]. Among these adjustments, an increase in bone mass [17], increased protein synthesis [20], increased muscle strength [21], functional improvement [22] and increased muscle mass even with short periods of training have been found [23].

To the best of our knowledge, only one study in the literature has examined the hypotensive effect following 60 minutes of traditional resistance exercise (RE) without BFR and low intensity RE with BFR (hypotension was observed only after RE without BFR at 70% of 1RM) [24]. Although not statistically significant, the above-mentioned study revealed a trend of BFR in reducing the total peripheral resistance index, which could result in a decrease of BP [24]. Thus, there is little evidence regarding the effects of BFR on BP response, especially for upper limb protocols.

In this context, obtaining similar hypotensive responses in the two types of training would be attractive for trained individuals to avoid the continuous use of high intensity loads. Thus, the present study aimed to compare the BP response of trained normotensive individuals to RE with and without BFR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects. We recruited eight male subjects (23.8 ± 4 years, 74 ± 3 kg, 174 ± 4 cm) who trained at least three times per week in the 24 months before the beginning of the study intervention. Before data collection, volunteers responded to the PAR-Q questionnaire and signed informed consent for participation, according to Resolution 196/96 of the National Board of Health, Ministry of Health (CNS / MS) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

The Ethics Committee of the Politec Faculty approved the research project. Individuals using medications, with a history of cardiovascular disease, with joint limitation or musculoskeletal problems that could influence the exercises, were excluded from the experiment.

Procedures

The subjects underwent four experimental sessions, with a 72-hour interval between them. We asked them to avoid any kind of physical exercise or caffeine intake and have a good night of sleep during the intervals between sessions. In the first visit the occlusion pressure, anthropometric measurements and 1RM were determined. The chosen exercises were biceps curl with dumbbells, biceps curl in the Scott bench, closed bench press and triceps extension. In the second visit, they repeated the 1RM tests for the determination of intraclass correlation coefficient and familiarization with the proposed exercises with or without blood flow restriction. In the third and fourth visits, the subjects were randomly assigned to the experimental protocols: traditional RE without BFR and RE with BFR.

Anthropometric measurements

Height was measured with the individual barefoot, back aligned to the stadiometer (Stanley Ambo, Ocenaside, CA), directing the view to the horizon and following a deep breath. Body mass (BM) was obtained through a mechanical scale (Balmak – Model 111, Santa Barbara do Oeste – SP, Brazil), 150 kg capacity, 100 g resolution, calibrated every 2 measures.

One-repetition maximum (1RM) test

All tests were performed with 10-min rest intervals between each exercise. The order of the exercises was as follows: biceps curl with dumbbells, closed bench press, biceps curl on the Scott bench and triceps extension. The protocol consisted of a light warm-up of 10 min of treadmill running followed by 8 repetitions at 50% of estimated 1RM (according to the participants’ capacity verified in the adaptation period). After a 1-min rest, subjects performed three repetitions at 70% of the estimated 1RM. Following three minutes of rest, participants completed 3–5 1RM attempts interspersed with 3–5-min rest intervals, with progressively heavier weights (5%) until the 1RM was determined. The range of motion and exercise technique were standardized according to the descriptions of Brown and Weir [25]. The intraclass correlation for the tests was: biceps curl with dumbbells, r = 0.98; closed bench press, r = 0.96; biceps curl on the Scott bench, r = 0.99; and triceps extension, r = 0.99.

Determination of occlusion pressure

The occlusion pressure (mmHg) was determined with a sphygmomanometer for BP (15 cm width and 51 cm length) and a Doppler vascular ultrasound device (DV-600, Marted, Americana, Sao Paulo, Brazil). The subjects remained seated and the sphygmomanometer was placed in the proximal region of the right upper arm and inflated until the auscultatory pulse of the brachial artery was interrupted [26]. We adopted the equivalent to 50% of the total occlusion pressure of each individual during the BFR session [27]. The mean occlusion pressure was 123.00 ± 11.00 mmHg and the mean pressure applied during the session was 61.00 ± 5.00 mmHg.

Experimental protocols

The traditional RE without BFR protocol consisted of three sets of ten repetitions at 70% 1RM, following a one-minute rest interval between sets and exercises (performed in the same order of the 1RM tests). In the low intensity RE with BFR, the subjects performed three sets of 15 repetitions at 20% 1RM load, with the same rest interval and exercise order of the traditional session. The cuff was deflated during the interval between exercises to avoid excessive discomfort.

Blood pressure measurement

Systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were measured with an oscillometric device (Microlife 3AC1-1, Widnau, Switzerland) according to the recommendations of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [3]. The cuff size was adapted to the circumference of the arm of each participant according to the manufacturer's instructions. All BP measures were assessed in triplicate (measurements separated by one minute) with the mean value used for analysis. Blood pressure measurements were performed after 15 min of seated rest (0), and 10 min, 20 min, 30 min, 40 min, 50 min and 60 min after the experimental sessions. During BP measurements participants remained seated quietly at a controlled room temperature.

Statistical analysis

Shapiro-Wilk test and Mauchly's test were used to analyze normality and sphericity of the data, respectively. A mixed ANOVA was used to compare the BP between and within experimental sessions (group x time). An LSD post hoc test was applied in the event of significance [28]. The power achieved in the study for SBP decrease greater than 10 mmHg was 97% and the effect size was 2.01. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Inc., v. 18.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for data analysis and G*Power 3.1.6 software to calculate power [29] were used.

RESULTS

Systolic blood pressure. There was an increase in SBP following traditional RE without BFR immediately after exercise (P = 0.006), and a decrease after 50 min (P = 0.015) when compared to baseline. There were no differences at 10 min (P = 0.143), 20 min (P = 0.056), 30 min (P = 0.169), 40 min (P = 0.058) and 60 min (P = 0.077) as compared with baseline (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Blood pressure at rest and after exercise.

| Traditional resistance exercise | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 119.1 ± 9.0 | 79.1 ± 3.4 |

| After exercise | 147.7 ± 18.1* | 76.0 ± 7.9 |

| After 10 min | 113.0 ± 9.2 | 84.7 ± 3.1 |

| After 20 min | 108.6 ± 9.4 | 82.5 ± 2.6 |

| After 30 min | 112.0 ± 11.5 | 81.3 ± 2.6 |

| After 40 min | 107.1 ± 11.3 | 80.0 ± 4.0 |

| After 50 min | 105.7 ± 10.8* | 78.9 ± 2.9 |

| After 60 min | 110.2 ± 11.2 | 84.2 ± 4.0 |

| Resistance exercise with blood flow restriction | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) |

| Baseline | 121.0 ± 7.8 | 76.5 ± 5.8 |

| After exercise | 133.2 ± 8.3* | 91.2 ± 16.5 |

| After 10 min | 113.0 ± 15.5 | 75.1 ± 7.7 |

| After 20 min | 112.0 ± 11.8* | 72.0 ± 8.4 |

| After 30 min | 111.1 ± 11.2 | 78.1 ± 8.4 |

| After 40 min | 113.5 ± 5.5* | 79.2 ± 7.0 |

| After 50 min | 115.2 ± 6.5* | 73.7 ± 7.1 |

| After 60 min | 115.1 ± 6.5* | 76.7 ± 7.2 |

Note: data are mean ± SD. SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure.

Significant difference as compared with baseline (P < 0.05).

Similarly, SBP showed an increase immediately after RE with BFR (P = 0.004), and a decrease at 20 min (P = 0.046), 40 min (P = 0.005), 50 min (P = 0.029) and 60 min (P = 0.011) after as compared with baseline. There was no alteration in SBP at 10 min (P = 0.140) and 30 min (P = 0.054) as compared with baseline (Table 1).

Diastolic blood pressure

There was no statistically significant difference for DBP following both protocols (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Greatest decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure

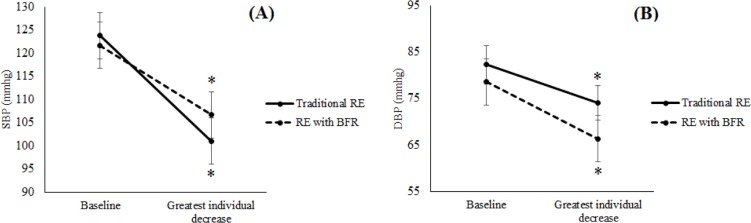

The greatest decrease of SBP (F (1.9) = 319.28, P = 0.001, eta2 = 0.97) and DBP (F (1.9) = 27.64, P = 0.001, eta2 = 0.75) values (greater individual decrease after exercise) were lower than baseline for both sessions. There were no differences between sessions (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Greatest decrease of systolic blood pressure (A) and diastolic blood pressure (B) following resistance training with and without blood flow occlusion.

SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, traditional RE = resistance exercise; RE with BFR = blood flow restriction.

*Significant difference from baseline (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The initial hypothesis of the present study has been confirmed, as both traditional RE and RE with BFR induced a decrease in SBP after exercise. Moreover, the greatest decrease in values of SBP and DBP were lower as compared with baseline following both protocols, without differences between them. In this sense, there was post-exercise hypotension following low-intensity BFR exercise, demonstrating it to be a work-efficient protocol. Thus, elderly persons who cannot train with heavy loads could benefit from this type of training without joint pain and damage [22]. In addition, the resistance exercise with blood flow restriction reduces cardiac preload during exercise, which may be beneficial in the rehabilitation of patients with heart problems [30].

The investigation into the behaviour of BP after RE with BFR is relatively new [2]. To date, this is the first study to investigate the changes in BP following RE with BFR for the upper limbs in trained subjects. Although our results are related to acute exercise, it has been shown that the magnitude of post-exercise hypotension (PEH) after an acute exercise session is associated with the training-induced decrease of BP. Hecksteden [31] reported that the magnitude of PEH following acute, maximal exercise is associated with the training-induced decrease of BP following a walking/running programme (45 min, four times per week at 60% HRR) during 4 weeks in healthy untrained subjects aged 30–60 years. Moreover, Tibana [32] revealed that the degree of BP reduction after acute RE is correlated with the magnitude of change in resting BP observed after 8 weeks of resistance training (whole body training with 3 weekly sessions and 3 sets of 8-12 repetitions maximum). Furthermore, from a clinical perspective, small decrements in SBP and DBP of even 2 mmHg reduce the risk of stroke by 14% and 17%, and the risk of developing coronary artery disease by 9% and 6%, respectively [33].

Although the protocol used in the present study is similar to other protocols, some factors possibly were decisive to lead to different results, such as the periods of BP collection, cuff pressure, size, time to deflate the cuff during the protocols and the muscle group involved. For example, one study used the equivalent of 200 mmHg of pressure, the cuff width was 5 cm, and the cuff was deflated every two exercises performed [24]. By contrast, our study used 50% of occlusion pressure of the brachial artery, the cuff width was 15 cm, and the cuff was deflated between all exercises.

Possibly, the above-mentioned factors were highly relevant for the divergent results found. Artery pressure of the narrow cuff is around 235 mmHg, and wide cuff pressure is about 144 mmHg [34]. In this way, Rossow [24] used an equivalent pressure of 85% of the total artery occlusion.

Another important issue in the present study was the use of the greatest decrease in BP values obtained individually following 60 minAnother important issue in the present study was the use of the greatest decrease in BP values obtained individually following 60 minutes of each training protocol. This reinforces the fact that the timing for post-exercise hypotension (PEH) may vary between individuals, and this should be taken into consideration in future studies.

Thus, RE with BFR seems to be an important tool to reduce BP [35] and may also be used by trained individuals to prevent cardiovascular complications and to avoid the excessive use of heavy loads. The mechanical pressure applied by the cuff during the muscle contractions leads to constriction of peripheral arterioles, causing a significant increase in resistance to blood flow [24]. This leads to reduced removal of metabolites and the sensation of pain during the BFR protocol, leading to the stimulation of type IV fibres (nociceptors, pain receptors). This mechanism results in electrical impulses to the central nervous system, producing instant changes in efferent activity of the central and peripheral nervous system. Such systems have a great influence on arteries and the heart, stimulating the exercise pressure reflex [1], which could reflect on PEH. Moreover, this stimulus may also lead to the release of several factors that reduce the sensitivity of blood vessels to adrenaline and also increase the release of nitric oxide, which is responsible for vasodilatation [1].

Finally, more studies are required to examine the possible mechanisms responsible for the hemodynamic response to RE with BFR, such as the activity of the autonomic nervous system, activation of the baroreflex and release of catecholamines.

This study has some limitations that are worth noting: the difficulty of standardizing food ingestion of the subjects, the small sample size, and the lack of a low intensity RE session without BFR.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that both traditional RE and RE with BFR cause hypotensive effects on BP, which may be important to prevent cardiovascular complications. These results should not be extrapolated to other subjects with different physical conditions.

Acknowledgements

The authors also acknowledge the financial support from CAPES.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.MacDonald JR. Potential causes, mechanisms, and implications of post exercise hypotension. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:225–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polito MD, Simão R, Senna GW, Farinatti PDTV. Efeito hipotensivo do exercício de força realizado em intensidades diferentes e mesmo volume de trabalho. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2003;9:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper RS, Wolf-Maier K, Luke A, Adeyemo A, Banegas JR, Forrester T, Giampaoli S, Joffres M, Kastarinen M, Primatesta P, Stegmayr B, Thamm M. An international comparative study of blood pressure in populations of European vs. African descent. BMC Med. 2005;31:2. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia Estatística (IBGE) Estatística de hipertensos; Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Souza JC, Tibana RA, Cavaglieri CR, Vieira DC, De Sousa NM, Mendes FA, Tajra V, Martins WR, Farias DL, Balsamo S, Navalta JW, Campbell CSG, Prestes J. Resistance exercise leading to failure versus not to failure: effects on cardiovascular control. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes AP, Doederlein PM. A review on post-exercise hypotension in hypertensive individuals. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;96:100–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tibana RA, Boullosa DA, Leicht AS, Prestes J. Women with metabolic syndrome present different autonomic modulation and blood pressure response to an acute resistance exercise session compared with women without metabolic syndrome. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2013;33:364–372. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tibana RA, Navalta JW, Bottaro M, Vieira D, Tajra V, Silva AO, Farias DL, Pereira GB, De Souza JC, Balsamo S, Cavaglieri CR, Prestes J. Effects of eight weeks of resistance training on the risk factors of metabolic syndrome in overweight /obese women - „A Pilot Study”. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardiologia SBD, Hipertensão SBD, Nefrologia SBD. VI Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. 2010;95(supl.1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pescatello LS, Franklin BA, Fagard R, Farquhar WB, Kelley GA, Ray CA. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:533–553. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000115224.88514.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battagin AM, Dal Corso S, Soares CL, Ferreira S, Leticia A, Souza C, Malaguti C. Pressure response after resistance exercise for different body segments in hypertensive people. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95:405–411. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2010005000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canuto PMBC, Nogueira IDB, Cunha ES, Ferreira GMH, Mendonça KMPP, Costa FA, Nogueira AMS. Influence of resistance training performed at different intensities and same work volume over BP of elderly hypertensive female patients. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2011;17:246–249. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mediano MFF, Paravidino V, Simão R, Pontes FL, Polito MD. Subacute behavior of the blood pressure after power training in controlled hypertensive individuals. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2005;11:337–340. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jannig PR, Cardoso AC, Fleischmann E, Coelho CW, CarvalhoI TD. Influence of resistance exercises order performance on post-exercise hypotension in hypertensive elderly. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2005;11:337–340. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomasi T, Simão R, Polito MD. Comparaçã do comportamento da pressão arterial após sessões de exercícios aeróbios e de força em indivíduos normotensos. R da Educação Física/UEM. 2008;19:361–367. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karabulut M, Abe T, Sato Y, Bemben MG. The effects of low-intensity resistance training with vascular restriction on leg muscle strength in older men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubo K, Komuro T, Ishiguro N, Tsunoda N, Sato Y, Ishii N, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T. Effects of low-load resistance training with vascular occlusion on the mechanical properties of muscle and tendon. J Appl Biomech. 2006;22:112–119. doi: 10.1123/jab.22.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takarada Y, Nakamura Y, Aruga S, Onda T, Miyazaki S, Ishii N. Rapid increase in plasma growth hormone after low-intensity resistance exercise with vascular occlusion. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000;88:61–65. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fry CS, Glynn EL, Drummond MJ, Timmerman KL, Fujita S, Abe T, Dhanani S, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Blood flow restriction exercise stimulates mTORC1 signaling and muscle protein synthesis in older men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2010;108:1199–1209. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01266.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamanaka T, Farley RS, Caputo JL. Occlusion training increases muscular strength in division IA football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26:2523–2529. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823f2b0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokokawa Y, Hongo M, Urayama H, Nishimura T, Kai I. Effects of low-intensity resistance exercise with vascular occlusion on physical function in healthy elderly people. Biosci Tren. 2008;2:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abe T, Beekley M, Hinata S, Koizumi K, Sato Y. Day-to-day change in muscle strength and MRI-measured skeletal muscle size during 7 days KAATSU resistance training: A case study. Int J KAATSU Training Res. 2005;1:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossow LM, Fahs CA, Sherk VD, Seo DI, Bemben DA, Bemben MG. The effect of acute blood-flow-restricted resistance exercise on postexercise blood pressure. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2011;31:429–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2011.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown L, Weir J. ASEP Procedures recommendation I: Accurate assessment of muscular strength and power. J Exerc Physiol Online. 2001;4:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurentino GC. Treinamento de Força com Oclusão Vascular: Adaptações Neuromusculares e Moleculares; São Paulo: Escola de Educação Física e Esporte, Universidade de São Paulo; 2010. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gualano B, Ugrinowitsch C, Neves JRM, Lima FR, Pinto AL, Laurentino G, Tricoli VAA, Lancha AH, Jr, Roschel H. Vascular occlusion training for inclusion body myositis: a novel therapeutic approach. J Vis Exp. 2010;42:250–254. doi: 10.3791/1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brace N, Kemp R, Snelgar R. SPSS for psychologists: A guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows, Versions 12 and 13; L. Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima T, Kurano M, Iida H, Takano H, Oonuma H, Morita T, Nagata T. Use and safety of KAATSU training: results of a national survey. Int J KAATSU Train Res. 2006;2:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hecksteden A, Greutters T, Meyer T. Association between postexercise hypotension and long-term training-induced blood pressure reduction: a pilot study. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23:58–63. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31825b6974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tibana RA, de Sousa NMF, Nascimento DC, Pereira GB, Thomas SG, Balsamo S, Simoes HG, Prestes J. Correlation between Acute and Chronic 24-Hour Blood Pressure Response to Resistance Training in Adult Women. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36:82–89. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1382017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, Cutler JA, Havas S, Kotchen TA, Roccella EJ, Stout R, Vallbona C, Winston MC, Karimbakas J. Primary prevention of hypertension: clinical and public health advisory from The National High Blood Pressure Education Program. JAMA. 2002;288:1882–1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loenneke JP, Fahs CA, Rossow LM, Sherk VD, Thiebaud RS, Abe T, Bemben DA, Bemben MG. Effects of cuff width on arterial occlusion: implications for blood flow restricted exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:2903–2912. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2266-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tibana RA, Pereira GB, Navalta JW, Bottaro M, Prestes J. Acute effects of resistance exercise on 24-h blood pressure in middle aged overweight and obese women. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34:460–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]