Abstract

Motivation: As the quantity of genomic mutation data increases, the likelihood of finding patients with similar genomic profiles, for various disease inferences, increases. However, so does the difficulty in identifying them. Similarity search based on patient mutation profiles can solve various translational bioinformatics tasks, including prognostics and treatment efficacy predictions for better clinical decision making through large volume of data. However, this is a challenging problem due to heterogeneous and sparse characteristics of the mutation data as well as their high dimensionality.

Results: To solve this problem we introduce a compact representation and search strategy based on Gene-Ontology and orthogonal non-negative matrix factorization. Statistical significance between the identified cancer subtypes and their clinical features are computed for validation; results show that our method can identify and characterize clinically meaningful tumor subtypes comparable or better in most datasets than the recently introduced Network-Based Stratification method while enabling real-time search. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to simultaneously characterize and represent somatic mutational data for efficient search purposes.

Availability: The implementations are available at: https://sites.google.com/site/postechdm/research/implementation/orgos.

Contact: sael@cs.stonybrook.edu or hwanjoyu@postech.ac.kr

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Due to advancements of genome scale sequencing data of patients, sequencing will become a common practice in medicine (Kim et al., 2012, 2013, 2014; Stratton, 2011; Stuart and Sellers, 2009). In the near future, the amount of patient records that include gene mutation data will be huge. As the quantity of genomic mutation data increases, the likelihood of finding patients with similar genomic profiles, for various disease inferences, increases. However, so does the difficulty in identifying them. Even with the significance of the impact and need, genomic-based patient similarity searching has not yet been actively studied by the bioinformatics community.

1.1 Types of genome data

Each type of genome data has different significance for each of the disease. However, the most commonly studied data that are expected to be associated with many of the disease, other than the gene expression, are the sequence mutation data. In the recent years, huge numbers of tumor samples have been sequenced in large-scale projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al., 2013) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) (Mardis, 2012; Watson et al., 2013). Due to the current limitations on the availability of patient data, we focus on mutation data from cancer patients, because such data are relatively abundant. However, the proposed method is not limited to (somatic) mutations alone and can further be extended to combine various types of genome data.

1.2 Somatic mutations and associated challenges

Somatic mutations are mutations that are not inherited from the parents. Assuming that fewer somatic mutations occur in normal cells than in cancer cells, a typical method to identify somatic mutations in cancer patients is to find the differences between genome sequences of normal tissues and cancer tissues (Greenman et al., 2007; Mardis, 2012; Watson et al., 2013). Characterizing cancer patients with somatic mutations is a natural process for cancer studies because cancer is the result of massive disruption of genes by various causes (Wang et al., 2011; Dulak et al., 2013). Note that with other diseases, somatic mutations may not be as significant as in cancer.

Somatic mutation data as well as other type of mutation data are sparse in character. That is, compared with all possible mutations, the actual number of mutations is small. Typically, 100–200 genes have somatic mutations among 20 000+ human genes for a cancer patient (Hofree et al., 2013)). Also, for complex diseases, including cancer, mutations are genetically heterogeneous (Marusyk et al., 2012)). That is, even for patients with similar clinical phenotype, raw mutational profiles can be divergent. Various efforts have focused on making sense of the heterogeneity, especially in cancer data (Dulak et al., 2013; Hofree et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2011). However, for our purpose, we focus on reducing the effect of heterogeneity in the identification of similar patients.

1.3 Gene-Ontology and orthogonal non-negative matrix factorization

The Gene-Ontology (GO) provides consistent and unified functional descriptions of genes and gene products across databases, and is used in various tasks including functional profiling of gene sets (Dennis et al., 2003; Khatri et al., 2004). Typical GO applications utilize terms at a particular depth in the GO hierarchy (Myers et al., 2006). However, such approach has the problem of biological terms in different levels of the GO hierarchy (Lord et al., 2003). Our method includes a proposal to solve this problem.

In various contexts, NMF is a widely used method for various clustering tasks and is known to be more accurate than other methods such as principal components analysis and singular vector decomposition (Lee and Seung, 1999; Xu et al., 2003). Orthogonal NMF (ONMF) puts an orthogonal constraint on creation of the basis vectors (or encoding vector) and is shown to improve the accuracy of NMF in clustering (Ding, 2006). Besides the clustering capability, NMF and ONMF have the potential for use in compact representations. However, the capability of NMF and ONMF in terms of indexing and searching in cancer genomics has not been widely explored. In this work, we exploit both the clustering and the representative capabilities of NMF and ONMF.

1.4 Characteristics of proposed method

The main characteristics of the proposed patient mutation profile are as follows:

Compact. The resulting patient mutation profiles have dimension <10, the number of the subtypes, which varies according to cancer types. This also removes the sparsity problem.

Enable real-time search. We can retrieve similar patients within 0.08 s using simulated data size of 10 000.

Tolerant to heterogeneity. The resulting profile shows tolerance to genetic heterogeneity, and tolerance to difference in diagnostic environments.

Directness in function interpretation. Mutations map to GO terms in which function interpretations can be made directly.

High predictive power for clinical features. The cancer stratification results show it has high predictive power (or high correlation) for clinical features (the histological basis feature or the survival time) compared with Network-Based Stratification (NBS) (Hofree et al., 2013).

2 Materials and Methods

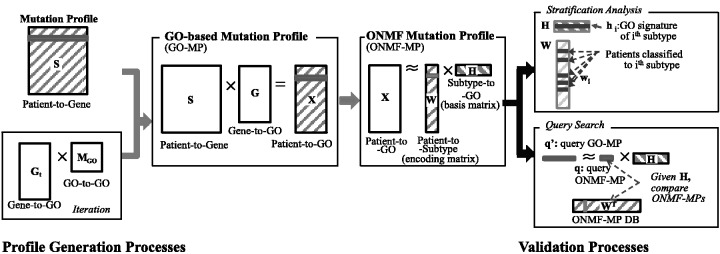

2.1 Overview of patient profile construction and validation

The first step in patient profile generation (Fig. 1) is to extract mutation profiles. We use somatic mutations to generate the mutation profiles of cancer patients. For each patient, a mutation profile is represented as a binary vector in which each entry is 1 if any of the somatic mutations is present in the gene compared with germ line, 0 otherwise. Next, GO-based mutation profiles (GO-MP) are obtained by multiplying the mutation profile matrix by the gene profile matrix. The gene profile matrix is constructed based on the gene-GO relationships. Each gene is represented as a binary vector in which each entry indicates a binary state of the association between gene and its GO terms. The influence of GO terms at non-leaf nodes spreads to their descendant terms according to the GO hierarchy. The influence spread is computed iteratively until only the GO terms at the leaf nodes have non-zero entries. Finally, a compact ONMF mutation profile (ONMF-MP), is obtained by using ONMF (Ding, 2006; Yoo and Choi, 2010) to factorize GO-MP and taking the encoding matrix as the profile of the patients. In experiments, analysis of cancer stratification is conducted to verify the quality of the proposed profiles, and top-k searches are performed with the ONMF-MP to verify real-time search capability and search characteristics.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the patient profile construction and validation processes. The mutation profiles are represented as a binary vector in which each entry indicates a binary state of a gene. The GO-based mutation profile matrix, X, is obtained by multiplying the mutation profile matrix, S, and the gene function profile matrix, G. The ONMF mutation profile matrix, W, is obtained by factorizing GO-MPs through ONMF. For stratification, we assign the patients to the cluster that has the highest value based on the encoding vector. For query search, the query profile is generated by minimizing reconstruction error between the mutation profile and the estimated profile multiplied by latent basis vector, and patients who are similar to a given query patient are identified by calculating the Euclidean distance between them and the query patient

2.2 Dataset

Somatic mutation information of level-2 exome and clinical data for ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) from TCGA were downloaded and filtered. Data from patients that have fewer than 10 mutations were discarded, because consistently capturing relations among patients requires at least 10 mutations. This filtering process left 441 patients with 12 431 genes for the OV data, 516 patients with 18 067 genes for the LUAD data, 247 patients with 20 446 genes for the UCEC data, 291 patients with 9341 genes for the GBM data and 772 patients with 13 078 genes for the BRCA data.

2.3 Constructing mutation profiles

GO functional terms and ONMF are used to construct proposed mutation profiles: GO-MPs and ONMF-MPs. Two major benefits of GO-based representation are that it reduces the genetic heterogeneity and sparsity, and that it enables direct function interpretation. The distinction of our approach in application of GO is that we take a genome-scale approach for GO-based function analysis in construction of the proposed mutation profiles. That is, unlike typical function profiling methods, in which a small number of preselected genes is analyzed to find the most relevant functional terms, we unbiasedly consider all genes during the analysis. Moreover, we use the most specific functional terms, i.e. the leaf node terms, to minimize the inter-correlations between terms. Benefits in using ONMF are that it further reduces the heterogeneity and makes the profile even more compact by separating out global signatures with sample weights for the signatures. Details of construction are as follows.

(Somatic) mutation profile, : For each patient, the mutation profile is represented as a binary vector in which each entry indicates the binary state of the gene; in case of somatic mutations, 1 if any of somatic mutations (i.e. a single-nucleotide base change and the deletion/insertion of bases) has occurred in the gene compared with the germ line (or normal tissue), 0 otherwise. As aforementioned, mutations occur heterogeneously even for patients with the same cancer type, and the frequency of occurrence is slight making the profile matrix S divergent and sparse.

Gene-function profile, : A gene-function profile is represented as a binary vector in which each entry indicates the binary state on a gene; 1 if a gene is associated with the GO term (information mapping gene sequence to accession number (gene2accession) and gene to GO term (gene2go) are obtained from NCBI), 0 otherwise. A GO term of a node is highly correlated with GO terms of its descendant nodes as well as its ancestor nodes due to its hierarchical structure (The GO hierarchy of biological processes (BPs) is from GO version 2014-02-02; Ashburner et al., 2000). To ensure that only qualified GO terms are used, GO terms of ‘Non-traceable Author Statement’ (NAS), ‘No biological Data available’ (ND) and ‘Not Recorded’ (NR) are ignored (Rhee et al., 2008). To reduce the term correlation, we use only the most specific terms, i.e. the leaf node term after propagating the scores of the non-leaf terms down to the leaf node terms. This approach also resolves the problem of evaluating genes annotated with general term as the effect of the gene of function identification is spread out over several leaf node terms. We do this by defining an asymmetric adjacency matrix of GO, , where entry (i, j) indicates the parent(i)-child(j) relationship, and only the diagonal entries of leaf nodes are 1. This matrix is further normalized according to the node degree. Equation for the iterative influence propagation is as follows:

| (1) |

where is the gene profile matrix at the t-th iteration. This process is repeated until converges (usually within 15 iterations), then the matrix entries of the non-leaf nodes become zero.

GO-based mutation profile (GO-MP), : The GO-MP is generated as , where S is the initial mutation profile matrix and G is the gene-function profile matrix using ‘BP’ domain of GO. By this process, each entry of a GO-MP becomes a weighted sum of the gene contributions on each GO term. The rows of the resulting are further quantile normalized to X by enforcing the distribution of the GO profiles to be identical. Using the mutation profile S without the gene-function profile, , usually shows reduction in the performance of the predictive power of clinical features (Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, we have tested different combinations of GO domains for generating gene-function profile matrix and BP domain showed the most consist and accurate results compared with other GO domain combinations (Supplementary Fig. S4).

ONMF mutation profile (ONMF-MP), : The GO-MP is further made compact by taking the encoding matrix W of ONMF on X (Eq. 2) as profile vectors. This process reduces the number of dimension of a patient profile to the number k of subtypes while maintaining all information contained in H. Details are provided in the next section.

2.4 Representation and stratification with ONMF

2.4.1 Non-negative matrix factorization

NMF factorizes a non-negative data matrix into non-negative basis vectors and their non-subtractive combinations. Specifically, given data matrix X with n observed data points , NMF seeks a decomposition of X as follows:

| (2) |

where H contains basis vectors and W contains encoding vectors that represent the extent to which each basis vector is used to reconstruct each input vector. More specifically, based on randomly initialized matrices W and H, NMF finds the solution of by applying the multiplicative update rules (Lee and Seung, 1999):

| (3) |

| (4) |

where indicates (i,j)-th element of the matrix X.

2.4.2 Orthogonal NMF

ONMF puts an orthogonal constraint on the encoding matrix () which generates signatures of subtypes that are orthogonal to each other. The ONMF allows emphasizing significant GO terms for each subtype, which make the interpretation easier. Also, ONMF have been shown to perform better than NMF for certain cases (Ding, 2006). To solve the optimization problem with orthogonal constraint on H, the Lagrangian, , is used as follows:

| (5) |

where Ω is the symmetric matrix containing Lagrangian multipliers. According to (Yoo and Choi, 2010), the multiplicative update rules can be derived by using the true gradient on Stiefel manifold:

| (6) |

where the update rule of W follows Equation (3). ONMF allows better interpretation of the factorized results and usually results in better clustering quality (Ding, 2006; Yoo and Choi, 2010). The dimension of ONMF-MP is determined based on the performance of the predictive power. For example, for UCEC and BRCA, the dimension used is four (Section 3.2.2).

2.4.3 Stratification and top-k search using ONMF

After factorizing X into the encoding matrix W and the basis matrix H, we use the encoding matrix for cancer stratification. Specifically, for stratification of patients into k-th subtypes, we assign patients to cluster which has the highest value based on the encoding vector, as:

| (7) |

In this work, to enable reuses of factorized matrices and to allow for real-time search capability, consensus clustering is not used. The dimension of ONMF-MP is determined based on the dimension that resulted in the best performance in the predictive power test (Section 3.2.2). Stratification using K-means have been tested. However, there were no significant differences in the results (Supplementary Fig. S1) showing that the proposed profiles are not dependent on the type of clustering methods used.

To retrieve top-k similar patients, it is required to compute query-patient similarity scores in the ONMF-MP. Thus we compare the vectors in the encoding matrix W with the ONMF-MP of a query patient, , where q is the GO-MP of a query patient. It is used to seek patients who are similar to a given query patient by calculating the Euclidean distance between the query profile and patient profiles in the database.

2.5 Search performance validation

We validated the proposed profiles using accuracy measures and speed calculation of top-k search results. In a top-k search, we used the similarity of clinical profiles to determine whether the search results are correct. Clinical profiles were constructed based on a set of clinical features that have statistically significant correlation with the cancer subtypes. Statistical significance was evaluated by the P value of log-rank test for the cancer subtypes on clinical features. We considered P value as significant.

Two types of clinical profiles were tested: profiles with single clinical feature and profiles with combinations of clinical features. The accuracy of top-k search using single features was computed by dividing the number of patients retrieved with the same clinical feature to that of the query patient by k, the number of patients searched. Overall accuracy of the dataset was computed by taking the average of the leave-one-out top-k search accuracies. Accuracy calculation using combination of clinical features was conducted similarly, except that two patients are determined as similar when the number of overlapped features over the entire number of features is larger than or equal to the threshold .

3 Results

3.1 Search accuracy and speed

In this section, we validated the effectiveness of the proposed profile by accessing its accuracy and speed measurement on the top-k search results using the ONMF-MP. The accuracy of ONMF-MP based top-k search was validated by empirical examination of search results and calculation of average search accuracy. The search speed was computed on expanded data to simulate a ‘big data’ search scenario.

3.1.1 Top-k search accuracy

We first looked at empirical examples of the search results on OV, LUAD, UCEC, GBM and BRCA data. We found examples of clinically meaningful similarities using the ONMF-MP for all five datasets. Table 1 shows selected examples of query patient and their top-1 search results with list of similar or same clinical features between the query and the top-1 retrieval.

Table 1.

Empirical examples of top-1 search results. Four-character alphanumeric codes are patient identifiers of the TCGA barcode that is given to each sample.

| Dataset | Query | Top-1 | Similar clinical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| OV | 1331 | 2548 | Same clinical stage (Stage IIIC) and histologic grade (G3). |

| LUAD | 4244 | 7724 | Both reformed smoker for less or equal to 15 years |

| UCEC | A0GQ | A18A | Same histological type (endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma); close clinical stages (ib and ia). |

| GBM | 0003 | 5411 | Same histological type (untreated primary (de novo)). |

| BRCA | A0SF | A0CZ | Both positive estrogen receptor status and positive progesterone receptor status; same historical type (Infiltrating Ductal Carcinoma). |

Next, we systematically evaluated the retrieval accuracies as described in the Section 2.5. In the experiment, a leave-one-out test of top-1 and top-10 nearest neighbor search was conducted on UCEC and BRCA data. The dimension of ONMF-MP that we used for both UCEC and BRCA data is four, which showed the best performance in the predictive power (Section 3.2.2). Experiments for OV, LUAD, and GBM are not provided due to insufficient clinical information. That is, the clinical features provided in TCGA for the three cancer types had too many missing values or were extremely skewed.

We calucluated the accuracy based on single clinical feature that had the best correlation with all compared methods. Using ONMF-MP on UCEC data, 79.04% of the patients had same histological types as their top-1 similar patient, and on average 65.83% of the patients had the same histological types as their top-10 patients. In contrast, the accuracy of GO-MP was 42.74% and 65.44% comparing top-1 and top-10, respectively. This shows that the ONMF-MP finds latent GO relationship among similar patients with reduced sensitivity to experimental environment than does GO-MP. According to the top-k search on the ONMF-MP on BRCA data, 73.42% of top-1 similar patients had the same estrogen receptor status. In contrast to that of UCEC data, GO-MP was more accurate than ONMF-MP (76.01%). However, using ONMF-MP, 80.39% of top-10 similar patients had the same clinical feature whereas only 77.78% were the same using GO-MP.

As a second systematic experiment, a combination of clinical features was used as truth-values of the search results for retrieving similar patients using raw somatic mutation profile, GO-MP and ONMF-MP. Again, only UCEC and BRCA data were used. For the clinical features of the UCEC, histological type, pathological grade, residual, and histICD03 were used. For clinical features of the BRCA, histological type, estrogen status, progesterone status and margin status were used (the descriptions of the clinical features are provided at https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/docs/dictionary/). The accuracy of top-10 nearest neighbor search on the three profiles shows that GO-MP and ONMF-MP improve the accuracy in finding clinically similar patients compared with raw somatic mutation profiles (Table 2).

Table 2.

Accuracy of top-10 search on ONMF-profile.

| UCEC | BRCA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity threshold (θ) | 50% | 75% | 50% | 75% |

| Somatic mutation | 73.95 | 60.12 | 86.54 | 58.37 |

| GO-based | 83.31 | 67.54 | 90.7 | 64.84 |

| ONMF-based | 87.34 | 71.53 | 89.91 | 65.03 |

3.1.2 Search speed and compactness

Profiles of the OV, LUAD, UCEC, GBM and BRCA, were expanded in order to simulate top-k search in a large dataset. The size of clinical bio-data continues to grow. However, it is still not large () enough to verify the top-k search efficiency of the proposed method in a ‘big data’ scenario. The simulated datasets were created by iteratively combining a randomly selected pair of profiles to create a new profile until we had 10 000 profiles for each cancer types. The speedup from mutation profile (dim. ) to GO-MP (dim. ) and then to the final ONMF-MP (dim. ) is not surprising because each step is basically a dimension reduction step (Table 3). Also, the speed improvement is expected to be more drastic when the dataset size increases, since the search process included the profile generation of the query data that takes up a constant factor of time (data not shown).

Table 3.

Average top-k search speed (milliseconds).

| Dataset | Somatic mutation | GO-based | ONMF-based (dim.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OV | 6709 ± 60 | 4492 ± 170 | 167 ± 47 (2) |

| LUAD | 11201 ± 391 | 4650 ± 78 | 165 ± 48 (8) |

| UCEC | 13208 ± 1524 | 4768 ± 47 | 197 ± 39 (3) |

| GBM | 7150 ± 72 | 4397 ± 129 | 204 ± 20 (4) |

| BRCA | 8990±78 | 4541 ± 149 | 185 ± 36 (4) |

3.2 Validation of cancer stratification

We verified the accuracy of the proposed profile by performing cancer stratification experiments and showing meaningful associations between the resulting subtypes and clinical features. We performed stratification tests using GO-MP and matrix decomposition methods NMF and ONMF, and compared the results to that of a recently introduced method called NBS (Hofree et al., 2013). NBS is a cancer stratification method that uses gene-gene networks to propagate the effect of somatic mutations across affected genes and their associated genes. We ran NBS using default parameters and gene-gene network on which NBS performed best, i.e. STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2011) for UCEC and HumanNet (Lee et al., 2011) for OV, LUAD, GBM and BRCA (information mapping gene sequence to accession number (gene2accession) and gene to GO term (gene2go) are obtained from NCBI). After stratification, selected subtypes were validated using two criteria: survival curves and predictive power. To be as fair as possible, we compared results only for the number of subtypes that are the most favorable to NBS as indicated by the log-rank test or the test and P value combination for each dataset.

3.2.1 Survival analysis

We performed survival analysis for each subtype using the Cox proportional hazards regression model (Fan and Li, 2002) implemented in the R survival package (Therneau, 1999). We compare a full model consisting of subtypes and clinical features against a baseline model that consists of clinical features only. The following clinical features were used for analysis of OV and GBM datasets: age, gender, clinical stage, histologic grade/type and residual surgical resection. In addition to those features, smoking history was used in the LUAD dataset. Analysis for UCEC and BRCA dataset were omitted due to highly skewed death rates.

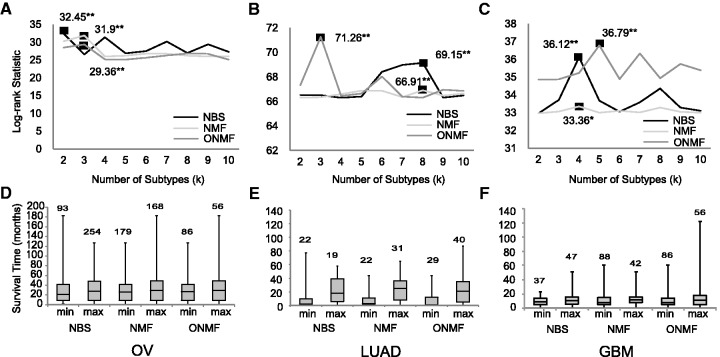

The log-rank statistics and associated P values were computed to compare survival distributions (or hazard functions) of two sample sets that are right-censored. Based on the best log-rank statistics, the ONMF result was more statistically significant than NBS result in two of three datasets. That is, on LUAD dataset, the best log-rank statistics value of ONMF, 71.26, was higher than that of NBS, 69.15 (Fig. 2B). Likewise, the best log-rank statistics value of NMF, 36.79, was slightly higher than that of NBS, 36.12 (Fig. 2C). Following the number of subtypes according to the highest log-rank statistics of NBS (Fig. 2A–C), we use results that stratify dataset to two subtypes for OV, eight for LUAD and four for GBM dataset, in the following analyses. Figure 2D–F shows the boxplots of the least aggressive subtype (max) and the most aggressive cancer subtype (min) based on the median survival time. Overall, the three approaches were comparable in that median survival time of the least and the most aggressive subtypes were in similar ranges. Examination shows that ONMF-MP is better at identifying the subtypes with patients having longer survival time for LUAD (Fig. 2E) and GBM (Fig. 2F) compared with NBS and NMF. Also, looking at survival time range, NBS assigned some patients with longer survival time to the most aggressive subtype (min) for OV (Fig. 2D) and LUAD (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Association of cancer subtypes and patient survival time for OV, LUAD and GBM data. A,B and C show log-rank statistics with maximum values marked (P value of significance of for A (OV), for B (LUAD), and for C (GBM) is indicated by k number of stars). D, E and F show boxplots of subtypes with minimum and maximum median survival time. The numbers of subtypes analyzed are two for OV, eight for LUAD, and four for GBM

Figure 3 shows the survival curve of patients in the min/max subtypes. The survival curves of all the subtypes are provided in the Supplementary Figure S3. In OV, the three survival curves showed similar pattern for the all three approaches. In LUAD, the all three methods showed clear separation between the maximum survival group and the minimal survival group. However, NBS produced inaccurate survival curves in which the min subtype shows longer survival pattern than the max subtype. In GBM data, NBS was successful at grouping the min survival whereas ONMF was better at grouping the max survival. Overall, the identified subtypes are good indicators of patient survival time (Figs 2D–F and 3). According to the result, NMF and ONMF showed comparable results to that of NBS, and ONMF shows the best stability (Fig. 2A–C).

Fig. 3.

Predicted survival curves for subtypes with minimum and maximum median survival time; x-axis is survival time (month) and y-axis is survival rate.

3.2.2 Predictive power

To verify the biological importance of the identified subtypes, we conducted experiments to investigate whether the identified subtypes are predictive of the observed clinical features. Statistical significance between the subtypes was evaluated using Pearson’s test, and associated P values were calculated when survival analysis is not possible due to biased death rates. The predictive power of clinical features was evaluated for UCEC and BRCA data and omitted for OV, LUAD and GBM data again due to biased death rates.

To analyze the predictive power of ONMF-MP on UCEC data, six clinical features were generated. The features were created based on histological basis (two histologic grades times three histological types). The identified subtypes extracted by our method were more closely associated with the clinical feature than NBS according to the best and P value combination (Table 4).

Table 4.

statistics of subtypes with histological basis feature on UCEC data

| Number of subtypes | NBS | GO-MP | ONMF-MP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 26.20 | ||

| 3 | 47.37 | ||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | |||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | |||

| 8 | |||

| 9 | |||

| 10 |

P value of significance of is indicated by k number of stars. The bold values are the highest value of statistics for each method.

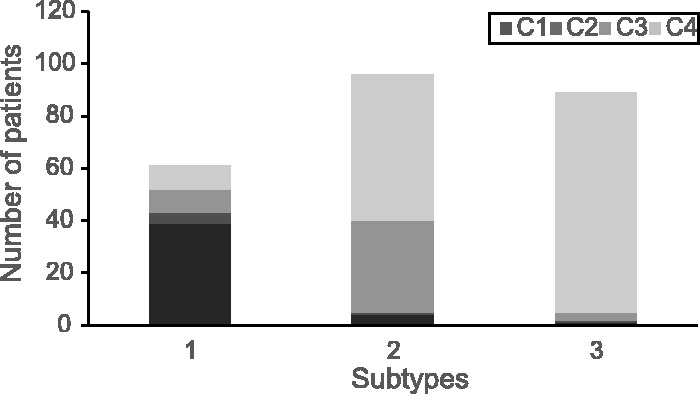

Also, the distribution of the features of the identified subtypes by ONMF-MP, evaluated on stratification that results in three subtypes, showed a clear distinction between subtypes (Fig. 4). That is, most patients with serous adenocarcinoma and high histological grade were included in the first subtype, patients with low histological grade were included in the second and third subtypes, and the patients with the combination of endometrioid type and high grade were included in the second subtype.

Fig. 4.

Association between UCEC cancer subtypes and histological clinical features. C1, (serous adenocarcinoma, High grade), C2, (other, High grade), C3, (endometrioid type, High grade), C4, (endometrioid type, Low grade). Only four features are presented and two features with low frequency () are omitted to increase the visibility

Predictive power of estrogen receptor status, which is categorized as intermediate, negative and positive, were evaluated on BRCA data (Table 5). The estrogen receptor status was highly correlated with the extracted subtypes by GO-MP and ONMF-MP. In addition, ONMF-MP produced subtypes with the highest correlations to the clinical features even for highly skewed features. Also, the values of ONMF-MP were larger than NBS and GO-MP in predicting histologic type, which is categorized in to three feature values that are highly skewed to ‘infiltrating lobular carcinoma (IDC)’ (82% of the samples). That is, only ONMF-MP was successful at grouping the patients with a minor feature, ‘IDC’ (10% of the samples), to a subtype.

Table 5.

statistics of subtypes and estrogen receptor status on BRCA data

| Number of subtypes | NBS | GO-MP | ONMF-MP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 32.49 | 108.48** | 101.51** |

| 3 | 33.51 | 123.72** | 103.28** |

| 4 | 55.51* | 115.31** | 113.5** |

| 5 | 39.91 | 96.84* | 100.42* |

| 6 | 43.63 | 87.17* | 86.69* |

| 7 | 43.55 | 93.94* | 103.8* |

| 8 | 38.92 | 81.22* | 91.98* |

| 9 | 42.29 | 75.71* | 78.23* |

| 10 | 39.84 | 75.43* | 87.23* |

P value of significance of is indicated by k number of stars. The bold values are the highest value of statistics for each method.

4 Conclusion

We proposed a compact representation for genome mutation. This representation is called the ONMF mutation profile (ONMF-MP); it is used for efficient search and characterization of patients’ genome data, and provides basic information for many data mining tasks in translational bioinformatics. The ONMF-MP uses ONMP to exploit the functional representation property of GO and the ability to correlate GO terms that are latent in a collection of genome mutation data. This representation solves the sparsity problem of mutation data and achieves reduced sensitivity to heterogeneous factors; it also enables genome-based real-time search for similar patients. We show experimentally that stratification results using the proposed representation have comparable or better correlations with clinical features than do those achieved using a recently introduced method. Insufficient clinical information prevents us from using the all five cancer types for the two the validation test to make the validation complete. However, this is not an inherent charateristic of the data and we expect that more data accumulation will evidentially resolve this problem. We also show that the representation can search through millions of patients in milliseconds.

Funding

“Basic Science Research Program” through the NRF of Korea funded by MSIP (NRF-2013R1A1A3005259), “Next-Generation Information Computing Development Program” through the NRF of Korea funded by MOE (2012M3C4A7033344), MSIP of Korea under the “ICT Consilience Creative Program” (IITP-2015-R0346-15-1007) supervised by IITP, and the ICT R&D program of MSIP/IITP (14-824-09-014).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ashburner M., et al. (2000) Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet., 25, 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G., et al. (2003) DAVID: Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol., 4, P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding C. (2006) Orthogonal nonnegative matrix tri-factorizations for clustering. In: 12th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Philadelphia, USA. ACM Press, pp. 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dulak A.M., et al. (2013) Exome and whole-genome sequencing of esophageal adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent driver events and mutational complexity. Nat. Genet., 45, 478–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Li R. (2002) Variable selection for cox’s proportional hazards model and frailty model. Ann. Stat., 30, 74–99. [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C., et al. (2007) Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature, 446, 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofree M., et al. (2013) Network-based stratification of tumor mutations. Nat. Methods, 10, 1108–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri P., et al. (2004) Onto-Tools: an ensemble of web-accessible, ontology-based tools for the functional design and interpretation of high-throughput gene expression experiments. Nucleic Acids Res., 32(Web Server issue), W449–W456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., et al. (2012) Indexing methods for efficient protein 3D surface search. In: DTMBIO 2012, San Francisco, USA. ACM Press, pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., et al. (2013) Efficient local ligand-binding site search using landmark mds. In: DTMBIO 2013, San Francisco, USA. ACM Press, pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., et al. (2014) Identifying cancer subtypes based on somatic mutation profile. In: DTMBIO . ACM, New York, NY, pp 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.D., Seung H.S. (1999) Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization. Nature, 401, 788–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I., et al. (2011) Prioritizing candidate disease genes by network-based boosting of genome-wide association data. Genome Res., 21, 1109–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord P.W., et al. (2003) Investigating semantic similarity measures across the Gene Ontology: the relationship between sequence and annotation. Bioinformatics, 19, 1275–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis E.R. (2012) Genome sequencing and cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 22, 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusyk A., et al. (2012) Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat. Rev. Cancer, 12, 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C.L., et al. (2006) Finding function: evaluation methods for functional genomic data. BMC Genomics, 7, 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S.Y., et al. (2008) Use and misuse of the gene ontology annotations. Nat. Rev. Genet., 9, 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton M.R. (2011) Exploring the genomes of cancer cells: progress and promise. Science, 331, 1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart D., Sellers W.R. (2009) Linking somatic genetic alterations in cancer to therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 21, 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D., et al. (2011) The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res., 39(Database issue), D561–D568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al. (2013) The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet., 45, 1113–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau T.M. (1999) A package for Survival Analysis in S. Technical report #53, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., et al. (2011) Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of arid1a in molecular subtypes of gastric cancer. Nat.Genet., 43, 1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson I.R., et al. (2013) Emerging patterns of somatic mutations in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet., 14, 703–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., et al. (2003) Document clustering based on non-negative matrix factorization. In: 26th ACM SIGIR. ACM New York, NY, USA, pp. 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J., Choi S. (2010) Nonnegative matrix factorization with orthogonality constraints. JCSE, 4, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.