Abstract

Context

Uncontrolled hypertension remains a widely prevalent cardiovascular risk factor in the U.S. team-based care, established by adding new staff or changing the roles of existing staff such as nurses and pharmacists to work with a primary care provider and the patient. Team-based care has the potential to improve the quality of hypertension management. The goal of this Community Guide systematic review was to examine the effectiveness of team-based care in improving blood pressure (BP) outcomes.

Evidence acquisition

An existing systematic review (search period, January 1980–July 2003) assessing team-based care for BP control was supplemented with a Community Guide update (January 2003–May 2012). For the Community Guide update, two reviewers independently abstracted data and assessed quality of eligible studies.

Evidence synthesis

Twenty-eight studies in the prior review (1980–2003) and an additional 52 studies from the Community Guide update (2003–2012) qualified for inclusion. Results from both bodies of evidence suggest that team-based care is effective in improving BP outcomes. From the update, the proportion of patients with controlled BP improved (median increase=12 percentage points); systolic BP decreased (median reduction=5.4 mmHg); and diastolic BP also decreased (median reduction=1.8 mmHg).

Conclusions

Team-based care increased the proportion of people with controlled BP and reduced both systolic and diastolic BP, especially when pharmacists and nurses were part of the team. Findings are applicable to a range of U.S. settings and population groups. Implementation of this multidisciplinary approach will require health system–level organizational changes and could be an important element of the medical home.

Context

Hypertension, defined as having systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg at two or more office visits or current use of BP-lowering medications, 1,2 remains the predominant risk factor for cardiovascular mortality in the U.S. 3,4 The prevalence of hypertension among U.S. adults (aged ≥ 18 years) from 2003 to 2010 was 30.4%—approximately 66.9 million adults.5 Estimated annual costs of hypertension are $93.5 billion per year1 and are projected to increase to $130.4 billion in 2030 if the status quo is maintained.6 Because 90% of adults with uncontrolled hypertension have a usual source of health care with insurance coverage, improving the quality of care for high BP is a priority, as reflected in the Healthy People 2020 objectives.5,7

Interventions aimed at improving hypertension care need to target both provider-related and patient-related barriers in order to accrue health benefits at the population level.1,8,9 One way is through innovative care delivery models such as the Chronic Care Model10,11 and the Patient-centered Medical Home (PCMH),12 which attempt to deliver effective interventions to all patients.13 A key feature of these care models is the incorporation of a multidisciplinary team for delivery of healthcare services. This team-based approach organizes care around patients’ needs and is frequently implemented with systems support for clinical decision making, collaboration, and patient self-management.10–12 Team-based care provides opportunities for care to be more patient centered by being more personalized, timely, collaborative, and empowering while also allowing providers more time to manage complex and critical issues.14

Previous systematic reviews have found team-based care to be effective in improving BP outcomes.15–17 Building on that foundation, this Community Guide systematic review examined current evidence on the effectiveness of team-based care in improving BP outcomes and the applicability of findings to various U.S. populations and settings using methods developed for The Community Guide.18,19 Important implementation aspects, such as the type of team member added and role of team members related to medication management, were evaluated, as was the potential benefit of team-based care extending to other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, such as high cholesterol and diabetes.

Evidence Acquisition

Systematic review methods used by The Community Guide can be found at www.thecommunityguide.org/about/methods.html.18,19 For this review, a coordination team was constituted, including subject matter experts on CVD from various agencies, organizations, and institutions together with qualified systematic reviewers from The Community Guide. The team worked under the oversight of the Community Preventive Services Task Force.

Conceptual Approach and Analytic Framework

The coordination team defined team-based care as adding new staff or changing the roles of existing staff to work with a primary care provider. Each team includes the patient, the patient’s primary care provider, and other professionals such as nurses, pharmacists, dietitians, social workers, and community health workers. These professionals complement the activities of the primary care provider by providing process support and sharing the responsibilities of hypertension care, which include medication management, active patient follow-up, and adherence and self-management support. Team-based care aims to facilitate communication and coordination of care support among various team members; enhance use of evidence-based guidelines by providers; establish regular, structured follow-up mechanisms to monitor patients’ progress and schedule additional visits as needed; and actively engage patients in their own care by providing them with education about hypertension medication, adherence support (for medication and other treatments), and tools and resources for self-management (including health behavior change).

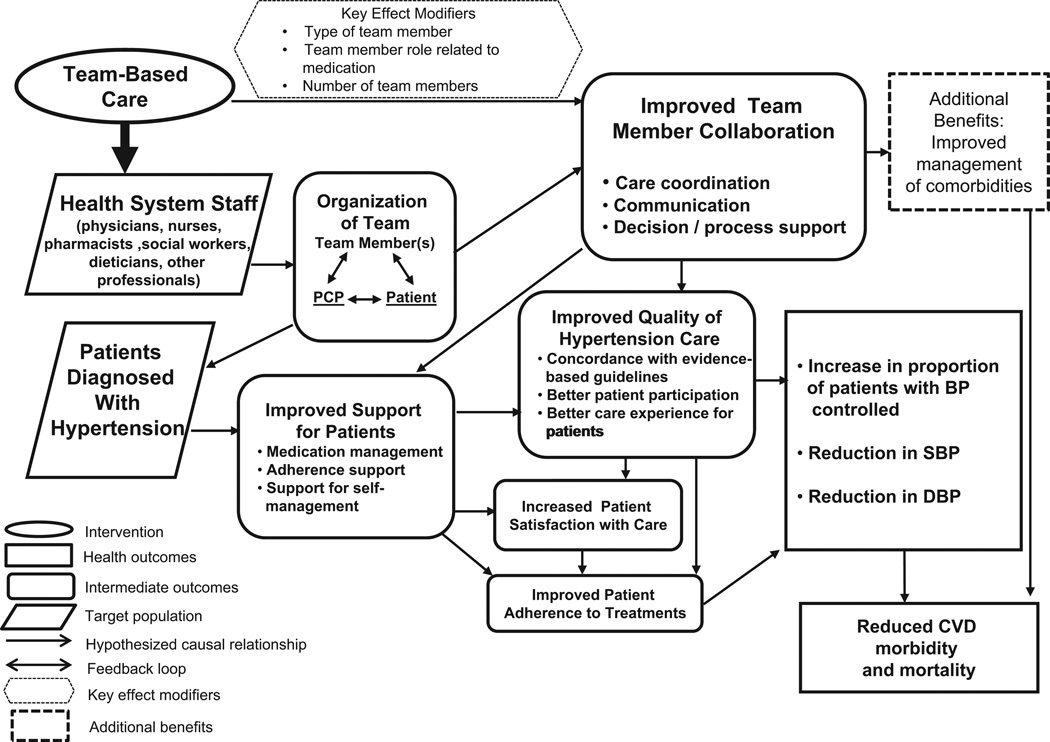

Organizing health system staff such as primary care providers, pharmacists, and nurses to work with patients diagnosed with hypertension leads to better patient support, team member collaboration, and quality of hypertension care. This organizational change is expected to improve outcomes for BP, CVD morbidity and mortality, patient-centered outcomes such as satisfaction with care and treatment adherence, and comorbid CVD risk factors such as diabetes and high cholesterol. Systems-level support, such as use of electronic health records, clinical decision support, and surveillance, frequently accompany team-based care efforts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Analytic framework: team-based care for improved blood pressure control

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PCP, primary care provider; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Search for Evidence

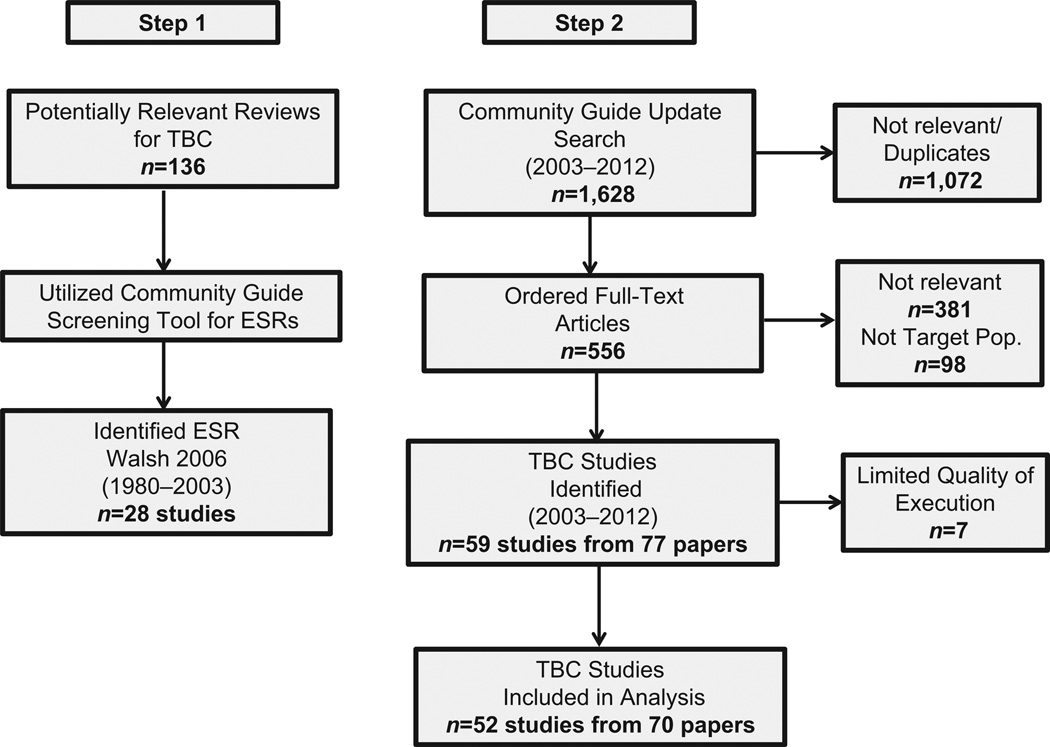

The search for evidence consisted of two steps (Figure 2). Step 1 involved locating existing systematic reviews on team-based care for BP control. Although multiple high-quality systematic reviews on this topic were identified,15–17 the systematic review by Walsh and colleagues17 had a conceptualization and methods similar to the Community Guide approach.18,19 Further, the scope adopted for the Walsh review reflected the team’s goal of examining the effectiveness of team-based care from a population health perspective. The literature search from this prior review17 ended in July 2003. Step 2 consisted of an updated search adopting the Walsh review’s search terms and databases.17 This Community Guide update covered the period from July 2003 to May 2012. The complete search strategy is available at www.thecommunityguide.org/cvd/supportingmaterials/SS-team-based-care.html. The remainder of this section discusses the methodology for the Community Guide review.

Figure 2.

Search process

ESR, existing systematic review; TBC, team-based care

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they

met the definition of team-based care as described in the conceptual framework;

were in English;

were not in the Walsh et al.17 review;

were conducted in a high-income economy20 consistent with Community Guide methods;

reported at least one BP outcome of interest (i.e., proportion of patients with controlled BP, reduction in SBP, or reduction in DBP);

included a comparison group or had an interrupted time-series design with at least two measurements before and after the intervention;

targeted populations with primary hypertension or populations with comorbid conditions such as diabetes as long as the primary focus of the intervention was BP control; and

did not include populations with secondary hypertension (e.g., pregnancy) or with a history of CVD (e.g., myocardial infarction).

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

Each study included in the current review was evaluated independently by two reviewers. Abstraction was based on the standard Community Guide process (www.thecommunityguide.org/methods/abstractionform.pdf). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Using Community Guide methods, each study was assessed for threats to internal and external validity.18 Threats to validity—such as poor descriptions of the intervention, population, sampling frame, and inclusion/exclusion criteria; poor measurement of exposure or outcome; lack of appropriate analytic methods; incomplete data sets; high attrition; or intervention and comparison groups not being comparable at baseline—were used to characterize studies as having good (0–1 limitations); fair (2–4); or limited (> 44) quality of execution. Studies judged to be of limited quality of execution were excluded from analysis.

Conclusions on the strength of evidence on effectiveness are based on evidence from both reviews (Walsh and colleagues17 and this Community Guide update), taking into account the number of studies, quality of available evidence, consistency of results, magnitude of effect estimates, and applicability considerations.18

Primary Outcomes of Interest

Three BP-related outcomes were the primary variables used to determine intervention effectiveness: proportion of patients with controlled BP and reduction of SBP and DBP (Figure 1). CVD-related morbidity (e.g., incidence of heart attacks and strokes) and mortality were also considered primary outcomes, if available.

Proportion of patients with controlled BP

The minimum requirements for this outcome were established standards for BP control (< 140/90 mmHg or < 130/80 mmHg for people with diabetes).2 Using data from the last available time point with ongoing team-based care, the absolute percentage point change in the proportion of patients receiving team-based care achieving BP control compared to patients in usual care was calculated for each study.

where

post=measurement from the last available time point with ongoing team-based care

pre=the last measurement before the intervention

prop=the proportion of patients with controlled BP

TBC=team-based care

UC=usual care.

An intent-to-treat analysis method was adopted wherein patients in both intervention and usual care groups that did not complete follow-up were considered to have uncontrolled BP. For a study with multiple team-based care intervention arms, a single effect estimate was calculated comparing the combined data from all intervention arms to usual care.

Reduction in SBP and DBP

For each study, the difference-in-differences of mean SBP or DBP was calculated based on the last time point measured while the intervention was in progress for patients receiving team-based care compared to patients receiving usual care. For studies with multiple team-based care intervention arms, the median individual effect estimate from each intervention arm represented a single data point in the analysis.

where

mean=average SBP or DBP level for each patient group

post=measurement from the last available time point with ongoing team-based care

pre=the last measurement before the intervention

TBC=team-based care

UC=usual care.

For the overall summary measure, the median of effect estimates from individual studies with the interquartile interval (IQI) was reported for each BP outcome.

Secondary Outcomes

Outcomes from one additional area were also analyzed when reported in included studies: patient-oriented outcomes, including medication adherence and satisfaction with care. Calculation of study-level and summary effect estimates followed the same methods as those for BP outcomes with comparable metrics, using proportions for dichotomous variables and means for continuous variables.

Evidence Synthesis

The existing systematic review by Walsh et al. 17 included 28 studies published between January 1980 and July 2003. For the current Community Guide review (July 2003–May 2012), 1,628 potentially relevant titles and abstracts were found, of which 77 articles21–97 representing 59 unique studies of team-based care were eligible for inclusion. Seven studies35,46,59,60,66,67,70 were judged to be of limited quality and excluded from all analyses. There-fore, 52 studies21–34,36–45,47–58,61–65,68,69,71–76,95–97 were included in the Community Guide review (Figure 2).

Both reviews indicated that team-based care resulted in substantial improvements in all BP outcomes (Table 1). The remainder of this paper provides detailed results from analysis of the 52 studies in the current Community Guide review.

Table 1.

Results from the systematic reviews of Walsh et al.17 and the Community Guide

| Outcome | Walsh (2006)17 1980–2003 |

Community Guide 2003–2012 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies |

Median effect estimate (IQI) |

Number of studies |

Median effect estimate (IQI) |

|

| Improvement in proportion of patients with controlled BPa |

9 (SBP) 6 (DBP) |

21.8 pct pts (9.0, 33.8) 17.0 pct pts (5.7, 24.5) |

33 (SBP+DBP) |

12.0 pct pts (3.2, 20.8) |

| Reduction in SBP | 17 | 9.7 mmHg (4.2, 14.0) | 44 | 5.4 mmHg (2.0, 7.2) |

| Reduction in DBP | 21 | 4.2 mmHg (0.2, 6.8) | 38 | 1.8 mmHg (0.7, 3.2) |

Absolute percentage point increase in proportion of patients achieving BP control

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; IQI, interquartile interval; pct pts, percentage points; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Study and Intervention Characteristics

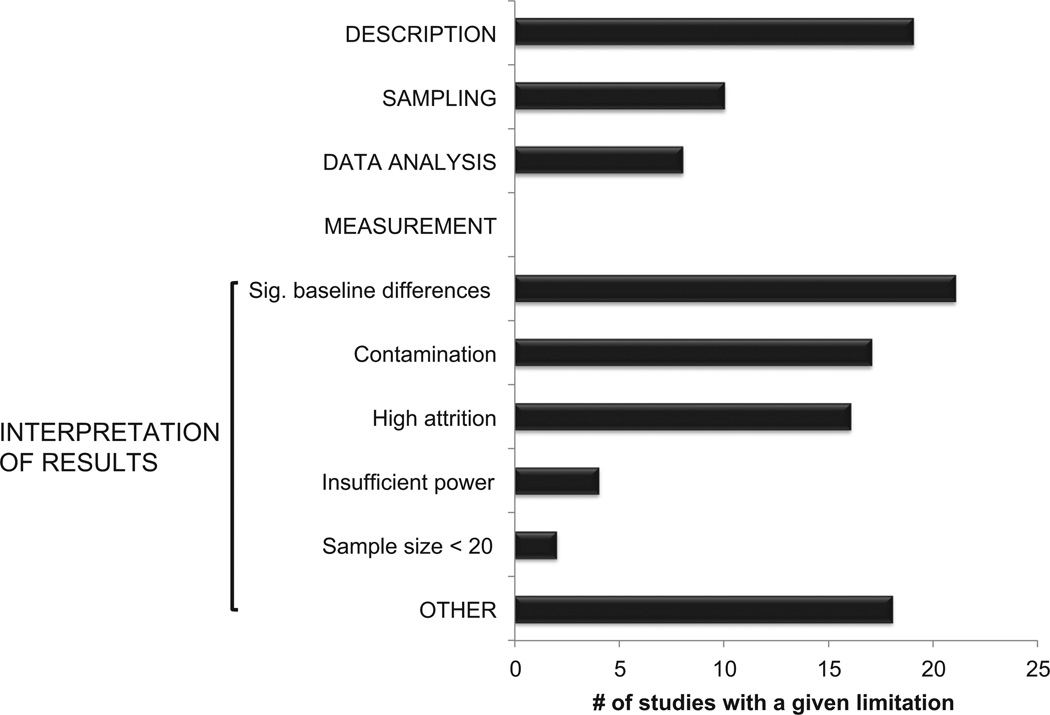

Limitations identified in the included studies showed significant differences in patient demographics between intervention and comparison groups at baseline, possible contamination within intervention and comparison groups, and issues related to inadequate description of populations and implemented interventions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Study limitations from Community Guide review (2003–2012, n=52)

Thirty-eight studies were conducted in the U.S.21–31,33,36–45,47–51,55,58,63–65,69,74,76,95–97 and the remaining studies in Europe34,52,54,56,57,61,73,75, Canada,32,53,62,68,72 and Japan.71 Forty-one studies21,22,24–27,30,31,33,34,36– 45,47,49–52,54–58,61,63,64,68,69,71–75,95,96 were implemented solely within healthcare settings and nine studies23,28,29,32,48,53,65,76,97 were implemented in community settings. One study was conducted both in a healthcare system and a community setting.62 Interventions were usually implemented across multiple settings in the healthcare system24–27,29–31,34,36–38,40,41,44,45,50,52,54–56,58,61,62,64,68,69,71,75 and in the community, where they were implemented in pharmacies32,53,76 and through home outreach visits.28,48,65,76,97 The median duration of team-based care interventions was 12 months (IQI=6–12 months). Only six studies29,39,40,57,63,75 addressed team-based care interventions delivered to more than 500 patients.

Team members who collaborated with patients and primary care providers were predominantly pharmacists, nurses, or both. Twenty-eight interventions21–23,25–28,34,36,38,40,41,43–45,49,50,52,56,57,64,65,72–75,95,97 included nurses, 15 interventions29–32,37,39,42,47,51,54,55,61,68,71,76 included pharmacists, and five interventions33,53,62,63,96 included both nurses and pharmacists. Detailed evidence tables are available at www.thecommunityguide.org/cvd/SETteambasedcare.pdf.

Population Characteristics

Study populations included adults and older adults and were balanced across gender (Table 2). For most studies, the majority of patients were either white or African American. Eight studies21,22,32,34,38,41,50,58 focused predominantly on populations where 450% of participants identified as low-income. In studies providing information on education level, the majority of participants identified as having a high school education or less.21,22,25,26,30,32,34,38,48,50,54,58 In six studies,36,38,41,42,50,58 more than half the population received either Medicare or Medicaid or were uninsured. In almost all studies22,23,25,28,30–33,37,40–44,48–54,56,57,62,68,71,75,76,95–97 that reported the proportion of patients with BP control as an outcome, most patients did not have their BP under control at baseline.

Table 2.

Population characteristics from included studies

| Characteristic | Number of studies (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Adult (18–64 years) | 40 (78) |

| Older adult (≥ 65 years) | 11 (22) |

| Gender | |

| ≥ 75% female | 5 (10) |

| ≥ 75% male | 7 (14) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Majority white | 17 (47) |

| Majority African American | 15 (41) |

| Majority Hispanic | 2 (6) |

| Majority other | 2 (6) |

| Income level | |

| Majority low-income | 8 (57) |

| Education level | |

| Majority high school or less | 11 (44) |

| Insurance status | |

| Majority with public insuranceb or uninsured |

6 (27) |

| BMI | |

| Majority <30 | 6 (26) |

| Majority ≥ 30 | 17 (74) |

| Baseline level of percentage with controlled BP | |

| 0 | 15 (42) |

| ≤ 50 | 16 (44) |

| > 50 | 5 (14) |

| Baseline mean SBP (mmHg) | |

| Majority ≥ 140 | 27 (61) |

| Majority < 140 | 17 (39) |

| Baseline mean DBP (mmHg) | |

| Majority ≥ 90 | 6 (16) |

| Majority < 90 | 32 (84) |

Total number of studies (and proportion) that reported specific demographic characteristics

Public insurance refers to Medicare and Medicaid.

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure

BP Outcomes

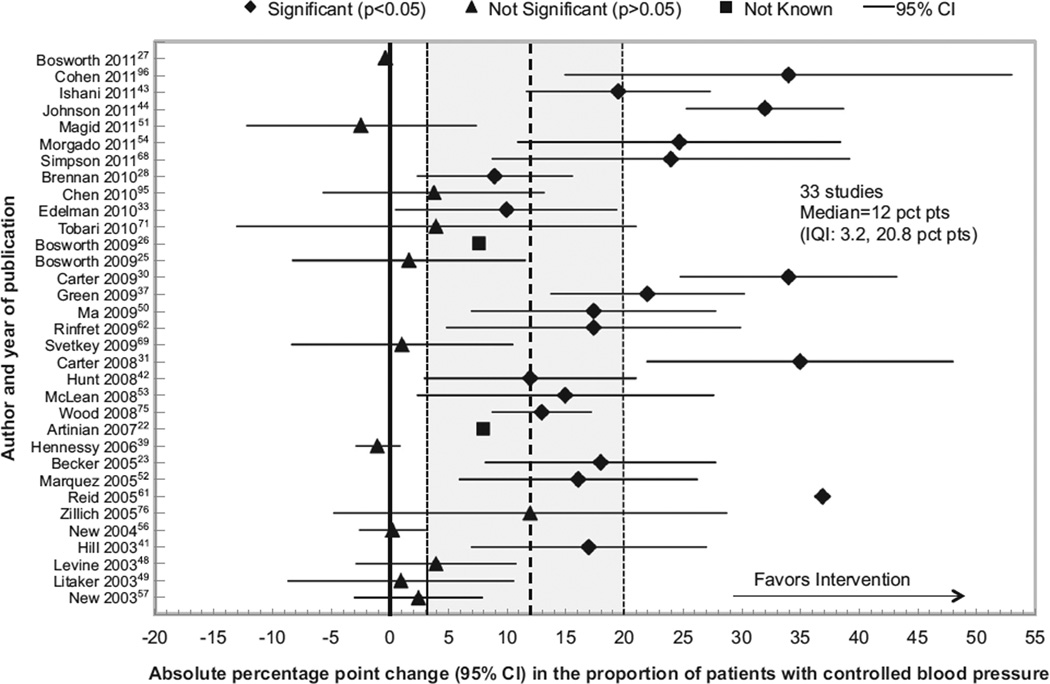

Proportion of patients with controlled BP

Figure 4 displays effect estimates and 95% CIs for the absolute percentage point (pct pt) change in patients with controlled BP from 33 studies22,23,25–28,30,31,33,37,39,41–44,48–54,56,57,61,62,68,69,71,75,76,95,96 comparing team-based care to usual care. Studies are shown chronologically by year of publication on the y-axis. Effect estimates displayed to the right of zero indicate improvement for patients receiving team-based care compared with usual care. The median effect estimate was 12 pct pts (IQI=3.2–20.8 pct pts). Most individual effect estimates in the favorable direction were significant (p < 0.05).23,28,30,31,33,37,41–44,50,52–54,61,62,68,96

Figure 4.

Changes in proportion of patients with controlled blood pressure attributable to team-based care, Community Guide review, 2003–2012

IQI, interquartile interval; pct pts, percentage points

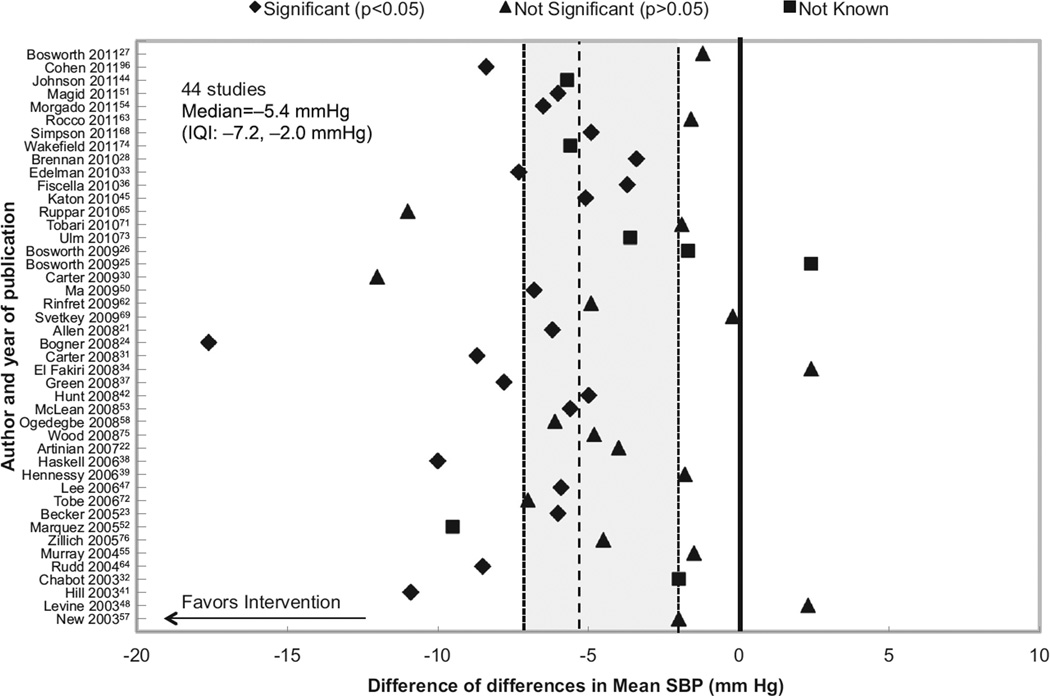

Reduction in SBP

Forty-four studies21–28,30–34,36–39,41,42,44,45,47,48,50–55,57,58,62–65,68,69,71–76,96 reported changes in SBP (Figure 5). Effect estimates to the left of zero indicate improvement in SBP for patients receiving team-based care compared with usual care. The median reduction in SBP was 5.4 mmHg (IQI=2.0–7.2 mmHg). Most individual effect estimates were significant (p < 0.05).21,23,24,28,31,33,36–38,41,42,44,45,47,50,53,54,64,68,96

Figure 5.

Changes in mean systolic blood pressure attributable to team-based care, Community Guide review, 2003–2012

IQI, interquartile interval; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Reduction in DBP

The overall median reduction in DBP was 1.8 mmHg (IQI=0.7–3.2 mmHg) from 38 studies.21–24,26–28,30–34,37–39,41,42,44,47,48,50–52,54,55,57,58,62–65,68,69,71–73,75,76

Additional evidence

Owing to differences in reporting, three studies could not be included in the main analyses.32,40,97 One study40 found that groups receiving team-based care had poorer BP outcomes than those receiving usual care (p > 40.05). Another study32 found high-income patients significantly more likely to have BP control with team-based care (p < 0.05), and the third97 reported slight improvements in BP control (p = 0.23) and SBP (p = 0.12) and no change in DBP (p = 0.37) for patients receiving home health visits.

Stratified Analyses for BP Outcomes

Setting

Improvement in the proportion of patients with controlled BP was similar for studies from both healthcare and community settings. The median effect estimate from studies within the Veterans Affairs (VA) system25,27,33,43,47,51,74,96 was 5.9 pct pts; an investigator involved in two VA studies25,27 postulated (H. Bosworth, Duke University School of Medicine, personal communication, 2012) that this lower number is likely due to elements of team-based care already instituted in usual care processes at the VA and high baseline levels of patients with controlled BP. Median reductions in SBP and DBP from these studies were similar to overall estimates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Blood pressure outcomes stratified by study and intervention characteristics

| Variable | Proportion of patients with BP controlled |

Reduction in SBP | Reduction in DBP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies |

Median estimatea (pct pts) |

Number of studies |

Median estimate (mmHg) |

Number of studies |

Median estimate (mmHg) |

|

| Location | ||||||

| U.S. | 23 | 10.0 | 32 | 5.8 | 27 | 1.8 |

| Non-U.S. | 10 | 15.6 | 12 | 4.9 | 11 | 1.7 |

| SETTING | ||||||

| Health-care /Clinical system | ||||||

| Allb | 27 | 12.0 | 36 | 5.7 | 31 | 1.8 |

| VA System | 6 | 5.9 | 7 | 5.9 | 4 | 1.8 |

| Community-basedb | 5 | 12.0 | 7 | 4.5 | 6 | 0.5 |

| Type of team member added | ||||||

| Nurse | 16 | 8.5 | 22 | 5.4 | 18 | 2.9 |

| Pharmacist | 11 | 22.0 | 13 | 5.0 | 13 | 1.7 |

| Nurse + Pharmacist | 4 | 16.2 | 5 | 5.6 | 3 | 3.5 |

| Other | 2 | 2.6 | 4 | 3.2 | 4 | 0.4 |

| Type of team member role related to medication | ||||||

| Independentc,d | 9 | 17.4 | 12 | 7.2 | 10 | 3.5 |

| PCP approvale | 11 | 15.0 | 11 | 5.0 | 9 | 1.7 |

| Support onlyd,f | 12 | 7.9 | 20 | 3.8 | 18 | 1.0 |

| Number of team members addedg | ||||||

| PCP + 1 team memberh | 20 | 10.5 | 25 | 5.6 | 24 | 1.4 |

| PCP + 2 team membersh |

6 | 13.5 | 8 | 5.3 | 7 | 3.2 |

| PCP + 3 or more team members |

5 | 17.0 | 8 | 5.9 | 5 | 3.0 |

| Baseline level of percentage with controlled BP | ||||||

| 0 | 14 | 14.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ≤ 50 | 14 | 14.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| >50 | 5 | 1.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Baseline SBP (mmHg) | ||||||

| ≥ 140 | NA | NA | 26 | 5.9 | NA | NA |

| < 140 | NA | NA | 16 | 5.0 | NA | NA |

| Baseline DBP (mmHg) | ||||||

| ≥ 90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 | 3.3 |

| < 90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 30 | 1.6 |

Absolute percentage point increase in proportion of patients achieving BP control

One intervention took place equally in the clinic and community.

Medication changes could be made by the team member independent of the PCP.

One study had multiple arms, each with a different type of team member role related to medication.

Team member could make medication recommendations and changes with PCP approval.

Team member could only provide adherence support and information on medication and hypertension.

Number of team members added refers to the type of team member (e.g., PCP þ pharmacist þ two nurses¼PCP þ 2 team members).

Two studies had multiple arms with different number of team members in each arm.

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; NA, not applicable; PCP, primary care provider; pct pts, percentage points; SBP, systolic blood pressure; VA, Veterans Affairs

Type of team member added

When pharmacists were added to teams, the median improvement in the proportion of patients with controlled BP was considerably higher than the overall estimate, but median reductions in SBP and DBP were similar to overall estimates (Table 3). When nurses alone or both nurses and pharmacists were added, median estimates for all BP outcomes were comparable to overall estimates. Only four studies24,48,58,69 examined the effectiveness of adding other team members, such as community health workers, integrated care managers, or behavioral interventionists without nurses or pharmacists, finding smaller effect estimates than those overall.

Type of team member role related to medication

Team member involvement in medication management was conceptualized as three levels: (1) team members could make changes to medications independent of the primary care provider (16 studies)21,23,27,33,36–38,40,41,43,49–51,64,72,96; (2) team members could provide medication recommendations and make changes with the primary care provider’s approval (15 studies)29–31,42,45,53–57,61,68,71,76,97; or (3) team members only provided adherence support and information on medication and hypertension (22 studies).22,24–28,32,34,39,44,47,48,52,58,62,63,65,69,73–75,95 One study examined multiple levels of team member roles using multiple study arms.27 The first two levels of medication management demonstrated larger improvements in BP outcomes than overall estimates (Table 3).

Number of team members added

Thirty-three interventions22,24–28,30–32,37,39,40,42–44,47,49,51,52,54–58,61,64,65,68,71–75 included one team member in addition to the primary care provider,1121,23,27,29,38,44,48,53,62,69,76 had two additional members, and 1033,34,36,41,45,50,63,95–97 involved three or more. Two studies27,44 with multiple study arms had different numbers of team members in each arm. Adding two or more members demonstrated larger improvements in the proportion of patients with controlled BP and reduction in DBP compared to adding only one; median reductions in SBP were similar regardless of team size (Table 3).

Baseline BP level

Fifteen studies22,30,31,33,37,42,44,51,52, 56,57,62,68,76,97 focused exclusively on patients with uncontrolled BP at baseline. In 14 studies,23,25,28,41,43,48– 50,53,54,71,75,95,96 ≤50% of the patients had controlled BP at baseline. Larger improvements in this outcome were found for these two groups compared to studies26,27,39,61,69 where > 50% of patients already had controlled BP at baseline. Similarly, 26 studies22,24,30– 34,36–38,41,42,44,48,51–55,57,58,62,64,72,73,76 that reported an average SBP ≥ 140 mmHg at baseline had a greater reduction in SBP than those where the average SBP was < 140 mmHg at baseline. This trend was also seen in six studies41,42,44,52,62,73 that had an average DBP reading ≥ 90 mmHg at baseline (Table 3).

Morbidity and Mortality

Two studies reported on morbidity and mortality from CVD-related events. One29 found significant decreases in both myocardial infarctions and any CVD-related event (OR=0.24 and 0.47, respectively, p < 0.05). Another study57 found that the team-based care group had 25 deaths compared to 36 deaths in the control group (OR=0.55, p < 0.05) after 12 months.

Medication Adherence and Patient Satisfaction with Care

Compared with patients in usual care, the proportion of patients receiving team-based care with “high” medication adherence (defined as taking medications as prescribed > 80% of the time) increased by a median of 16.3 pct pts.24,32,33,42,47,51,52,54,76 Two studies42,45 reported “satisfaction with care” at 12 months. In one study,42 high patient satisfaction scores were seen for hypertension care in both the team-based and usual care groups (p = 0.75) with no significant association between satisfaction and BP goal achievement (p = 0.40). The other study,45 comparing a team-based care approach that focused on diabetes, heart disease, or both with usual care, found an improvement of 14.0 pct pts in the proportion of patients reporting satisfaction with care (p < 0.001).

Applicability of Findings

Findings from this review are applicable to the U.S. healthcare system in both clinic- and community-based settings, especially when nurses and pharmacists are part of the team. Larger improvements in BP were found when team members could prescribe medications independent of the primary care provider or with their approval. However, improvements were also found when team members could only provide patients with hypertension information and support, indicating applicability to all levels of medication management.

White and African American populations were well represented across the included studies. Findings should be broadly applicable to various populations and settings in the U.S. Team-based care models are likely applicable in addressing BP control in patients with comorbidities such as diabetes: nine studies33,49,53,56,57,68,72,74,95 targeted BP control in people with diabetes and four studies45,50,51,97 had study populations in which the majority also had diabetes.

Additional Benefits and Potential Harms

Outcomes for diabetes and cholesterol, other CVD risk factors often comorbid with hypertension, also were analyzed. Team-based care resulted in improvements for most lipid- and diabetes-related outcomes, suggesting potential benefits for comprehensive CVD risk reduction (Table 4). Key features of interventions that improved outcomes other than BP were a team-based focus on multiple risk factors and addition of nurse practitioners who could prescribe medications independently, based on standard clinical protocols. Going beyond CVD prevention, two studies24,45 reported a reduction in depressive symptoms from team-based care interventions.

Table 4.

Changes in lipid and diabetes outcomes attributable to team-based care

| Variable | Change in mean | Change in proportion of patients at goal |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid outcome | ||

| Total cholesterol | −.3 mg/dL (6 studies)21,34,38,49,50,56 | 13.0 pct pts (3 studies)41,57,75 |

| LDL cholesterol | −4.3 mg/dL (11 studies)21,23,25,34,36,38,45,47,50,63,90,96 | 3.2 pct pts (5 studies)23,43,75,95,96) |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.3 mg/dL (6 studies)21,23,34,38,49,50 | −6.0 pct pts (1 study)41 |

| Triglycerides | −7.9 mg/dL (5 studies)21,23,34,38,50 | No studies |

| Diabetes outcome | ||

| A1C level | −0 3% (11 studies)21,25,33,36,45,49,50,63,72,74,96 | 10.0 pct pts (6 studies)33,41,43,75,96 |

| Blood glucose | −7.0 mg/dL (5 studies)23,34,38,44,50 | NA |

HDL, low-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NA, not applicable; pct pts, percentage points

No harm to patients were identified from team-based care interventions in the included studies or the broader literature. Team-based care is well suited to addressing potential adverse effects from hypertension medications through providing support for patients about medications as well as proactive follow-up and monitoring.

Considerations for Implementation

Team-based care implementation must be considered at multiple overlapping levels. In most U.S. health systems, successful implementation will likely require reorganization of patient care roles and responsibilities. An important consideration is resource allocation to support providers who implement team-based care. Reimbursement mechanisms need to support key elements that sustain benefits from team-based care. These include incentives for improving patient outcomes, training, performance feedback, clinical decision support systems, and communications support.

Findings suggest that team member roles that allow for changes to medication regimens using evidence-based clinical protocols, either independent of primary care providers or with their approval, are more effective than merely providing information and adherence support to patients. Health systems will need to make decisions about team size, the number and type of team members, and team member roles that are best suited for their specific needs.

Providing patient support for participation in self-management activities is vital. Support can range from educational resources on health behavior change to community-based peer support groups. This support could also be facilitated via various modalities for communication, such as mobile phones, smartphones, and patient web portals.98

Conclusions

Summary of Findings

There is strong evidence that team-based care is effective in improving BP outcomes, especially when pharmacists and nurses are part of the team. These findings are broadly applicable to various U.S. settings and population groups. Further, an independent Community Guide review99 of economic evidence indicates that team-based care for BP control is cost-effective. Implementation of this multidisciplinary team-based approach requires organizational change within the healthcare system.

Evidence Gaps

Although African Americans were well represented in included studies, more evidence is needed on team-based care for other minorities and low-SES populations. Included studies rarely analyzed outcomes by variables such as race, ethnicity, income level, education level, and insurance status. Further, patient-centered outcomes such as satisfaction with care and adherence to behavioral change activities need further study.

Regarding team composition, more studies are needed to evaluate team-based care models that incorporate other providers, such as community health workers and dietitians. Another vital aspect that was missing from most studies is information on the types of interactions between team members.

Evidence on scalability of team-based care was sparse. More evidence is needed on the implementation of team-based care in large populations covering multiple sites and from multi-year evaluations.

Discussion

Team-based care is a complex intervention with considerable heterogeneity in implementation for different populations and settings. A formal meta-analysis was, therefore, not considered ideal for this review because sufficient homogeneity is required for meta-analysis estimates to be useful by themselves.100 This review used descriptive statistics that facilitate simple and concise summaries of the distribution of study results. In addition, to be useful to public health decision makers, findings on the applicability of results to various U.S. populations and settings were based on stratified analyses, albeit in a univariate manner (Table 3).

Although observational studies with concurrent comparison groups in addition to RCTs were included in this review, only five included studies employed an observational study design. The lack of observational studies in this review could limit understanding of team-based care in real-world settings, as well as barriers to implementation. Examination of a funnel plot suggests potential publication bias, with two of the largest studies reporting small improvements in the proportion of patients with controlled BP. However, this needs to be considered within the complex nature of team-based care implementation. Finally, the focus of this review was to assess the effectiveness of team-based care in preventing CVD from ever happening by controlling BP at the population level; therefore, populations with a history of CVD were excluded.

A recent evidence report14 on team-based care for hypertension reached conclusions similar to this review: It called for teams of primary care providers, pharmacists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals to work with patients, especially in a medical home context. This push for coordinated care is furthered by the advent of accountable care organizations that operate on reimbursement models tied to quality metrics and targeting lower costs.101 Team-based care is central to the medical home and accountable care approaches and can help health systems provide a method to improve the efficiency of care delivery, offer a platform of support for patient access to resources for self-management activities, and achieve a comprehensive approach to treating comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, and obesity. In addition, team-based care can facilitate progress toward achieving the triple aim: improved health, a better care experience for patients, and reduced per capita costs.102

A recent IOM report103 explores both individual and organizational values behind successful teams in health care and calls for “investments in the people and processes that lead to improved outcomes.” The Community Guide team attempted to collect information on strategies used to address potential barriers to implementation and increase motivation for team-based care. Strategies included involvement of providers in designing the intervention, stakeholder and patient engagement, basing implementation on “models of best practice” or “effective trials,” putting business models in place, including reimbursement mechanisms and incentives, use of resources to implement team-based care (i.e., by restructuring existing resources or investment in new resources); making tools available for patients (e.g., websites) and providers (e.g., electronic health records); implementing motivational processes for team members (e.g., team-building sessions); and establishing systems to monitor and evaluate processes. Although available information on any of these elements was sparse in the included studies, it is crucial that these factors be considered by implementers of team-based care.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Michael Schooley, David Callahan, Diane Dunet, and the Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention (CDC) for their support at every step of the review. Barry Carter; Jeanette Daly (both at the University of Iowa); Kathryn MacDonald (Stanford University); and Paula Yoon (Division of Epidemiology, Analysis, and Library Services, CDC) provided guidance during the initial conceptualization. Kimberly Lane and Heba Athar (both CDC) contributed to review processes. Randy Elder, Kate W. Harris, and Onnalee Gomez (all from the Community Guide Branch, CDC) provided input on various stages of the review and the development of the manuscript.

Current and previous author affiliations are shown at the time the research was conducted. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.CDC. Vital signs: prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension —U.S., 1999–2002 and 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. The preventable causes of death in the U.S.: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Vital signs: awareness and treatment of uncontrolled hypertension among adults—U.S., 2003–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the U.S.: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(8):933–944. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthy People. Heart disease and stroke. 2020 www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=21.

- 8.Ogedegbe G. Barriers to optimal hypertension control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(8):644–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.08329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825–834. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner E, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berenson RA, Hammons T, Gans DN, et al. A house is not a home: keeping patients at the center of practice redesign. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(5):1219–1230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Davis C, et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27(2):63–80. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter BL, Bosworth HB, Green BB. The hypertension team: the role of the pharmacist, nurse, and teamwork in hypertension therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14(1):51–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter BL, Rogers M, Daly J, Zheng S, James PA. The potency of team-based care interventions for hypertension: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1748–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005182. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005182.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh JM, McDonald KM, Shojania KG, et al. Quality improvement strategies for hypertension management: a systematic review. Med Care. 2006;44(7):646–657. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000220260.30768.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based Guide to Community Preventive Services—methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1S):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1S):44–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The World Bank. Country and lending groups. data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups.

- 21.Allen JK, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Szanton SL, et al. Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Trial: a randomized, controlled trial of nurse practitioner/community health worker cardiovascular disease risk reduction in urban community health centers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(6):595–602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Artinian NT, Flack JM, Nordstrom CK, et al. Effects of nurse-managed telemonitoring on blood pressure at 12-month follow-up among urban African Americans. Nurs Res. 2007;56(5):312–322. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000289501.45284.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker DM, Yanek LR, Johnson WR, Jr, et al. Impact of a community-based multiple risk factor intervention on cardiovascular risk in black families with a history of premature coronary disease. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1298–1304. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157734.97351.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogner HR, de Vries HF. Integration of depression and hypertension treatment: a pilot, randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):295–301. doi: 10.1370/afm.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Dudley T, et al. Patient education and provider decision support to control blood pressure in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2009;157(3):450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Grubber JM, et al. Two self-management interventions to improve hypertension control: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):687–695. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, et al. Home blood pressure management and improved blood pressure control: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan T, Spettell C, Villagra V, et al. Disease management to promote blood pressure control among African Americans. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(2):65–72. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunting BA, Smith BH, Sutherland SE. The Asheville Project: clinical and economic outcomes of a community-based long-term medication therapy management program for hypertension and dyslipidemia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2008;48(1):23–31. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1996–2002. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carter BL, Bergus GR, Dawson JD, et al. A cluster randomized trial to evaluate physician/pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(4):260–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chabot I, Moisan J, Gregoire JP, Milot A. Pharmacist intervention program for control of hypertension. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(9):1186–1193. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelman D, Fredrickson SK, Melnyk SD, et al. Medical clinics versus usual care for patients with both diabetes and hypertension: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):689–696. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Fakiri F, Bruijnzeels MA, Uitewaal PJ, Frenken RA, Berg M, Hoes AW. Intensified preventive care to reduce cardiovascular risk in healthcare centres located in deprived neighbourhoods: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15(4):488–493. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282fceac2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erickson SR, Ascione FJ, Kirking DM. Utility of electronic device for medication management in patients with hypertension: a pilot study. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2005;45(1):88–91. doi: 10.1331/1544345052843084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiscella K, Volpe E, Winters P, Brown M, Idris A, Harren T. A novel approach to quality improvement in a safety-net practice: concurrent peer review visits. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1231–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30778-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green BB, Cook AJ, Ralston JD, et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(24):2857–2867. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haskell WL, Berra K, Arias E, et al. Multifactor cardiovascular disease risk reduction in medically underserved, high-risk patients. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(11):1472–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hennessy S, Leonard CE, Yang W, et al. Effectiveness of a two-part educational intervention to improve hypertension control: a cluster-randomized trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(9):1342–1347. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.9.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hicks LS, Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ, et al. Impact of computerized decision support on blood pressure management and control: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):429–441. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill MN, Han HR, Dennison CR, et al. Hypertension care and control in underserved urban African American men: behavioral and physiologic outcomes at 36 months. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16(11 Pt 1):906–913. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunt JS, Siemienczuk J, Pape G, et al. A randomized controlled trial of team-based care: impact of physician-pharmacist collaboration on uncontrolled hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):1966–1972. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0791-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishani A, Greer N, Taylor BC, et al. Effect of nurse case management compared with usual care on controlling cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1689–1694. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson W, Shaya FT, Khanna N, et al. The Baltimore Partnership to Educate and Achieve Control of Hypertension (The BPTEACH Trial): a randomized trial of the effect of education on improving blood pressure control in a largely African American population. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011;13(8):563–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Landon BE, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, et al. Improving the management of chronic disease at community health centers. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(9):921–934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa062860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2563–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levine DM, Bone LR, Hill MN, et al. The effectiveness of a community/academic health center partnership in decreasing the level of blood pressure in an urban African-American population. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(3):354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Litaker D, Mion L, Planavsky L, Kippes C, Mehta N, Frolkis J. Physician-nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients’ perception of care. J Interprof Care. 2003;17(3):223–237. doi: 10.1080/1356182031000122852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma J, Berra K, Haskell WL, et al. Case management to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease in a county health care system. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1988–1995. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magid DJ, Ho PM, Olson KL, et al. A multimodal blood pressure control intervention in 3 healthcare systems. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(4):e96–e103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marquez Contreras E, Vegazo Garcia O, Claros NM, et al. Efficacy of telephone and mail intervention in patient compliance with antihypertensive drugs in hypertension ETECUM-HTA study. Blood Press. 2005;14(3):151–158. doi: 10.1080/08037050510008977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McLean DL, McAlister FA, Johnson JA, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of community pharmacist and nurse care on improving blood pressure management in patients with diabetes mellitus: study of cardiovascular risk intervention by pharmacists-hypertension (SCRIP-HTN) Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(21):2355–2361. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morgado M, Rolo S, Castelo-Branco M. Pharmacist intervention program to enhance hypertension control: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(1):132–140. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9474-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray MD, Harris LE, Overhage JM, et al. Failure of computerized treatment suggestions to improve health outcomes of outpatients with uncomplicated hypertension: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(3):324–337. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.4.324.33173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.New JP, Mason JM, Freemantle N, et al. Educational outreach in diabetes to encourage practice nurses to use primary care hypertension and hyperlipidaemia guidelines (EDEN): a randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2004;21(6):599–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.New JP, Mason JM, Freemantle N, et al. Specialist nurse-led intervention to treat and control hypertension and hyperlipidemia in diabetes (SPLINT): a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2250–2255. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ogedegbe G, Chaplin W, Schoenthaler A, et al. A practice-based trial of motivational interviewing and adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(10):1137–1143. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park MJ, Kim HS, Kim KS. Cellular phone and Internet-based individual intervention on blood pressure and obesity in obese patients with hypertension. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(10):704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Planas LG, Crosby KM, Mitchell KD, Farmer KC. Evaluation of a hypertension medication therapy management program in patients with diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2009;49(2):164–170. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reid F, Murray P, Storrie M. Implementation of a pharmacist-led clinic for hypertensive patients in primary care—a pilot study. Pharm World Sci. 2005;27(3):202–207. doi: 10.1007/s11096-004-2563-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rinfret S, Lussier MT, Peirce A, et al. The impact of a multi-disciplinary information technology-supported program on blood pressure control in primary care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(3):170–177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.823765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rocco N, Scher K, Basberg B, Yalamanchi S, Baker-Genaw K. Patient-centered plan-of-care tool for improving clinical outcomes. Qual Manag Health Care. 2011;20(2):89–97. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e318213e728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rudd P, Miller NH, Kaufman J, et al. Nurse management for hypertension A systems approach. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(10):921–927. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruppar TM. Randomized pilot study of a behavioral feedback intervention to improve medication adherence in older adults with hypertension. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(6):470–479. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181d5f9c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schroeder K, Fahey T, Hollinghurst S, Peters TJ. Nurse-led adherence support in hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2005;22(2):144–151. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scisney-Matlock M, Makos G, Saunders T, Jackson F, Steigerwalt S. Comparison of quality-of-hypertension-care indicators for groups treated by physician versus groups treated by physician-nurse team. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2004;16(1):17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2004.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simpson SH, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Lewanczuk RZ, Spooner R, Johnson JA. Effect of adding pharmacists to primary care teams on blood pressure control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):20–26. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Svetkey LP, Pollak KI, Yancy WS, Jr, et al. Hypertension improvement project: randomized trial of quality improvement for physicians and lifestyle modification for patients. Hypertension. 2009;54(6):1226–1233. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taylor CT, Byrd DC, Krueger K. Improving primary care in rural Alabama with a pharmacy initiative. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(11):1123–1129. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/60.11.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tobari H, Arimoto T, Shimojo N, et al. Physician-pharmacist cooperation program for blood pressure control in patients with hypertension: a randomized-controlled trial. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(10):1144–1152. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tobe SW, Pylypchuk G, Wentworth J, et al. Effect of nurse-directed hypertension treatment among First Nations people with existing hypertension and diabetes mellitus: the Diabetes Risk Evaluation and Microalbuminuria (DREAM 3) randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2006;174(9):1267–1271. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ulm K, Huntgeburth U, Gnahn H, Briesenick C, Purner K, Middeke M. Effect of an intensive nurse-managed medical care programme on ambulatory blood pressure in hypertensive patients. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103(3):142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wakefield BJ, Holman JE, Ray A, et al. Effectiveness of home telehealth in comorbid diabetes and hypertension: a randomized, controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2011;17(4):254–261. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wood DA, Kotseva K, Connolly S, et al. Nurse-coordinated multi-disciplinary, family-based cardiovascular disease prevention programme (EUROACTION) for patients with coronary heart disease and asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a paired, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9629):1999–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zillich AJ. Hypertension outcomes through blood pressure monitoring and evaluation by pharmacists (HOME study) J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Dudley T, et al. The Take Control of Your Blood pressure (TCYB) study: study design and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(1):33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Gentry P, et al. Nurse administered telephone intervention for blood pressure control: a patient-tailored multifactorial intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, McCant F, et al. Hypertension Intervention Nurse Telemedicine Study (HINTS): testing a multifactorial tailored behavioral/educational and a medication management intervention for blood pressure control. Am Heart J. 2007;153(6):918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cene CW, Yanek LR, Moy TF, Levine DM, Becker LC, Becker DM. Sustainability of a multiple risk factor intervention on cardiovascular disease in high-risk African American families. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(2):169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Datta SK, Oddone EZ, Olsen MK, et al. Economic analysis of a tailored behavioral intervention to improve blood pressure control for primary care patients. Am Heart J. 2010;160(2):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dennison CR, Post WS, Kim MT, et al. Underserved urban African American men: hypertension trial outcomes and mortality during 5 years. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(2):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dolor RJ, Yancy WS, Jr, Owen WF, et al. Hypertension Improvement Project (HIP): study protocol and implementation challenges. Trials. 2009;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Goessens BM, Visseren FL, Sol BG, de Man-van Ginkels JM, van der Graaf Y, Group SS. A randomized, controlled trial for risk factor reduction in patients with symptomatic vascular disease: the multi-disciplinary Vascular Prevention by Nurses Study (VENUS) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13(6):996–1003. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000216549.92184.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Green BB, Anderson ML, Ralston JD, Catz S, Fishman PA, Cook AJ. Patient ability and willingness to participate in a web-based intervention to improve hypertension control. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Green BB, Ralston JD, Fishman PA, et al. Electronic communications and home blood pressure monitoring (e-BP) study: design, delivery, and evaluation framework. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(3):376–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ma J, Lee KV, Berra K, Stafford RS. Implementation of case management to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in the Stanford and San Mateo Heart to Heart randomized controlled trial: study protocol and baseline characteristics. Implement Sci. 2006;1:21. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McLean DL, McAlister FA, Johnson JA, King DM, Jones CA, Tsuyuki RT. Improving blood pressure management in patients with diabetes: the design of the SCRIP-HTN study. Can Pharm J. 2006;139(4):36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A, Richardson T, et al. An RCT of the effect of motivational interviewing on medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Powers BJ, Olsen MK, Oddone EZ, Bosworth HB. The effect of a hypertension self-management intervention on diabetes and cholesterol control. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rozenfeld Y, Hunt JS. Effect of patient withdrawal on a study evaluating pharmacist management of hypertension. Pharmacother-apy. 2006;26(11):1565–1571. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.11.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Von Muenster SJ, Carter BL, Weber CA, et al. Description of pharmacist interventions during physician-pharmacist co-management of hypertension. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(1):128–135. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weber CA, Ernst ME, Sezate GS, Zheng S, Carter BL. Pharmacist-physician comanagement of hypertension and reduction in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1634–1639. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wentzlaff DM, Carter BL, Ardery G, et al. Sustained blood pressure control following discontinuation of a pharmacist intervention. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011;13(6):431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen EH, Thom DH, Hessler DM, et al. Using the Teamlet Model to improve chronic care in an academic primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(S4):S610–S614. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cohen LB, Taveira TH, Khatana SA, Dooley AG, Pirraglia PA, Wu WC. Pharmacist-led shared medical appointments for multiple cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(6):801–812. doi: 10.1177/0145721711423980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pezzin LE, Feldman PH, Mongoven JM, McDonald MV, Gerber LM, Peng TR. Improving blood pressure control: results of home-based post-acute care interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):280–286. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Handler J, Lackland DT. Translation of hypertension treatment guidelines into practice: a review of implementation. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(4):197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Community Preventive Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease prevention and control: team-based care to improve blood pressure control. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.003. www.thecommunityguide.org/cvd/teambasedcare.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Lenz M, Steckelberg A, Richter B, Mühlhauser I. Meta-analysis does not allow appraisal of complex interventions in diabetes and hypertension self-management: a methodological review. Diabetologia. 2007;50(7):1375–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0679-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meyer H. Many accountable care organizations are now up and running, if not off to the races. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(11):2363–2367. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core principles & values of effective team-based health care. Washington DC: IOM; 2012. [Google Scholar]