Abstract

Introduction

Globally, women constitute 50% of all persons living with HIV. Gender inequalities are a key driver of women's vulnerabilities to HIV. This paper looks at how these structural factors shape specific behaviours and outcomes related to the sexual and reproductive health of women living with HIV.

Discussion

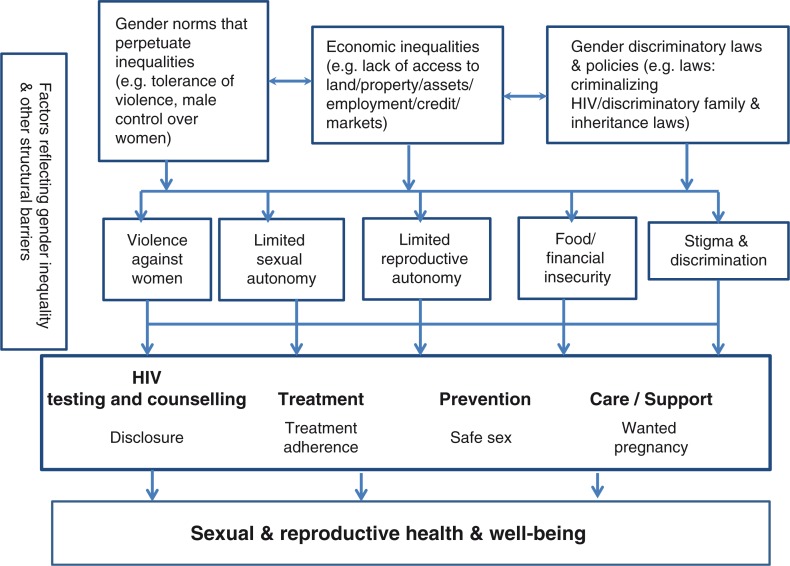

There are several pathways by which gender inequalities shape the sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing of women living with HIV. First, gender norms that privilege men's control over women and violence against women inhibit women's ability to practice safer sex, make reproductive decisions based on their own fertility preferences and disclose their HIV status. Second, women's lack of property and inheritance rights and limited access to formal employment makes them disproportionately vulnerable to food insecurity and its consequences. This includes compromising their adherence to antiretroviral therapy and increasing their vulnerability to transactional sex. Third, with respect to stigma and discrimination, women are more likely to be blamed for bringing HIV into the family, as they are often tested before men. In several settings, healthcare providers violate the reproductive rights of women living with HIV in relation to family planning and in denying them care. Lastly, a number of countries have laws that criminalize HIV transmission, which specifically impact women living with HIV who may be reluctant to disclose because of fears of violence and other negative consequences.

Conclusions

Addressing gender inequalities is central to improving the sexual and reproductive health outcomes and more broadly the wellbeing of women living with HIV. Programmes that go beyond a narrow biomedical/clinical approach and address the social and structural context of women's lives can also maximize the benefits of HIV prevention, treatment, care and support.

Keywords: gender inequalities, stigma, discrimination, laws, sexual and reproductive health

Introduction

Globally, women constitute half of all persons living with HIV. In sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest burden of HIV, women constitute 57% of persons living with HIV; and adolescent girls and young women are twice as likely to be living with HIV as compared to boys and young men. In low- and middle-income countries, female sex workers are 13.5 times more likely to be living with HIV as compared to the general population of women in reproductive age groups [1]. Globally, transgender women are 49 times more likely to be living with HIV as compared to all adults of reproductive age groups [2–4].

The sexual and reproductive health needs of women living with HIV require particular attention because these women are disproportionately vulnerable to certain reproductive health problems as compared to HIV-negative women and also in relation to the prevention of vertical transmission of HIV. Studies show that, as with women who are HIV negative, women living with HIV have high rates of unintended pregnancy and low rates of contraceptive use including condom use [5–9]. In sub-Saharan Africa, women living with HIV are significantly more likely to die during pregnancy or the postpartum period as compared to HIV-negative women [10,11]. Globally, women living with HIV are also more likely to have a higher incidence and progression of cervical neoplasia as compared to women who are HIV negative [12].

There has been increasing attention given to certain aspects of reproductive health of women living with HIV, particularly in the context of preventing vertical transmission of HIV. However, much of this focus has largely addressed the biomedical/clinical and health systems factors [13–15]. There has been less attention to a more holistic response that goes beyond disease prevention and addresses the sexual, emotional and mental health as well as social and economic wellbeing of women living with HIV as a legitimate focus of programming and research in its own right [16,17]. This state of affairs stands in stark contrast to what women living with HIV have articulated as their needs and priorities. These needs include the importance of addressing gender inequalities, violence against women, financial security and social support, reproductive health beyond pregnancy, and sexuality in a positive framework [18]. The UNAIDS Gap Report [3] highlights women living with HIV as one of the 12 priority populations. The report identifies stigma and discrimination, gender inequalities, and punitive laws and policies as three of the top four reasons for their vulnerability.

Nearly two decades of research and programming have highlighted that gender inequalities are a key structural driver of women's vulnerability to acquiring HIV. The importance of addressing gender inequalities is well recognized in key global commitments to ending HIV. Some countries are beginning to address them as part of their national HIV and AIDS responses [19,20]. However, concrete actions on a significant scale and in a sustained manner with concomitant resources are yet to materialize. The pathways by which gender inequalities shape women's risk of acquiring HIV are increasingly being mapped out, particularly as they relate to the intersections of intimate partner violence and HIV [21–23]. There is a small, but increasing body of evidence on interventions that work to address gender inequalities as a structural driver of women's risk of becoming infected with HIV, such as those that promote egalitarian gender norms, empower women and girls economically and in their sexual and reproductive decision-making, and reduce violence against women [23–27].

While gender inequalities affect HIV-negative women as well as women living with HIV in many similar ways, the latter face unique challenges related to stigma and discrimination, as well as pressures related to their sexual and childbearing decisions, economic security, mental health and emotional wellbeing. This paper describes how gender inequalities shape the sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing of women living with HIV, specifically via the following pathways: (1) unequal power relations, harmful gender norms and violence against women; (2) women's unequal access to and control over economic resources; (3) stigma and discrimination; and (4) punitive laws and gender-discriminatory policies. These pathways are examined in terms of four interrelated outcomes: (1) disclosure of HIV status; (2) ability to have safe and pleasurable sex; (3) fulfilment of fertility intentions and enabling of reproductive choices; and (4) management of treatment. The concept of wellbeing is included to underscore the importance of considering mental and emotional health as well as social and economic factors.

Unequal power relations in sexual and reproductive decision-making: the role of harmful gender norms and violence against women

In many settings, gender norms privilege men's control over women or perpetuate unequal power relations. These norms prevent women from having autonomy in sexual and reproductive health decisions. Surveys of women of reproductive age (e.g. demographic and health surveys) show that in many settings, a large proportion of married women, especially young women, do not have a final say in their own healthcare decisions [3,28,29]. Analysis of sexual behaviours of women and men from surveys shows that in general, married women find negotiation of safer sex and condom use much more difficult than do single women [30].

In many societies, women living with HIV, like others, face tremendous social pressures to bear children. Women gain status and their worth is proven through their fertility. Research highlights the importance of partners’ dominance in decision-making with respect to condom use and desire for children in shaping the sexual and reproductive decisions of women living with HIV as well as in the uptake of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) services [31–34]. Hence, women, including those living with HIV, face pressures to have unprotected sex in order to conceive or are unable to use contraception because of such social norms [18,35–37].

Gender norms related to sexuality confer different expectations for women and men to have consensual sex [38–40]. For women, a central issue is that of freedom from violence, which is a stark expression of men's power, control and entitlement over women. Globally 30% of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime [41,42]. Data show that intimate partner violence against women is associated with a 1.5-fold increase in risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or HIV in some regions [41]. Data on prevalence of intimate partner violence among women living with HIV are not easily obtained. However, one systematic review of studies from the United States of America highlighted a higher proportion of women living with HIV experiencing partner violence as compared to women in the general population [43]. A large body of studies from sub-Saharan Africa show that women's fear or experience of violence are a major barrier to HIV disclosure [44,45]. Studies on HIV disclosure outcomes among women living with HIV show that rates of negative outcomes, including violence, range from 3 to 15% and up to 59% in a couple of studies [46–48]. Studies also show an association between partner violence and lower uptake of PMTCT, continued or increased sexual risk behaviours and poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy – in part explained by stress, poor mental health, and a lack of control over health-promoting behaviours [43,49–53].

Unequal access to and control over economic resources: the role of food insecurity and lack of property and inheritance rights

An increasing number of studies highlight that, while antiretroviral therapy (ART) access has improved, there continue to be socio-economic barriers to uptake of and adherence to treatment. Food insecurity has been identified as a key barrier to ART adherence and quality of life for people living with HIV by a number of studies [54–56]. Women are disproportionately susceptible to food insecurity because of their lack of access to and control over economic resources in the form of ownership of land, assets and other property, and their lower access to formal employment than men. Research from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia highlights how women living with HIV are denied their property and inheritance rights by relatives when their husbands die due to HIV-related conditions [57–60].

This denial of land and property rights contributes to food insecurity, which in turn increases sexual risk taking (e.g. transactional or commercial sex) and limits women's ability to leave abusive relationships. For example, a study from Swaziland and Botswana highlighted that food insecurity among women was associated with significantly higher odds of inconsistent condom use with a non-primary partner, transactional sex and lack of control in sexual relationships, but that these associations were weaker among men [61]. Similar findings were shown in a qualitative study on food insecurity among women living with HIV in Uganda [62]. Studies also highlight women's economic dependency and their fear of being abandoned as a barrier to HIV disclosure [44,45,63,64]. Other adverse consequences of food insecurity on women living with HIV are in relation to their increased nutritional and energy requirements during pregnancy and lactation as well as the increased stress and burden on them to procure food and clean water for family members, including children who may also be living with HIV [65–67].

Stigma and discrimination

Stigma and discrimination are among key barriers that women living with HIV face in achieving their sexual and reproductive health. While all those who are living with HIV can face stigma because of judgments made about their behaviours by families and communities, women are more likely to be blamed because many societies have different expectations and standards for women's sexual conduct than for men's [68,69]. Moreover, in sub-Saharan Africa, as women are more likely to be tested first in the context of PMTCT programmes, they are also more likely to be blamed for bringing HIV into the family [44,45,70]. This potential consequence is likely not only to affect women's willingness to disclose their HIV status, but also to compromise their safety due to threats or experience of violence. Some women living with HIV report rejection of sexual relations by their partners or inability to find sexual partners because of their HIV status [18,71]. Women living with HIV may also experience internalized stigma that includes fear and anxiety that partners may not find them attractive [70,72,73]. In some settings, HIV programme staff discourage women living with HIV to have sex or blame them as being irresponsible if they have unprotected sex, which can affect their sexual, emotional and mental health and wellbeing [74,75].

For a number of women living with HIV who want children, there are pressures from institutions such as healthcare to not bear children [76]. Data from Bangladesh, the Dominican Republic and Ethiopia show that between a quarter to nearly half of all women living with HIV were advised by health workers to not have children [77]. Reports of women living with HIV being coerced into sterilizations have occurred in several settings (e.g. Bangladesh, Chile, Dominican Republic, Honduras, El Salvadaor, Mexico, Nicaragua and Namibia) [3,78]. Several countries surveyed as part of the stigma index (i.e. a survey-based tool to assess or measure levels of stigma experienced by people living with HIV) reported the proportion of women living with HIV who were denied family planning services in the last 12 months to be at least 10% [4]. These data highlight the contradictory pressures that women living with HIV face in relation to their fertility intentions and reproductive choices. The enactment of these contradictory pressures on women by healthcare institutions violates their reproductive rights.

Laws that criminalize HIV transmission and gender-discriminatory HIV policy responses

Laws that criminalize HIV transmission, exposure and non-disclosure are not only unjust and difficult to enforce, but make for poor public health practice and outcomes by disempowering those living with HIV and discouraging them from testing, accessing treatment programmes or disclosing their HIV status [79]. Despite this, 61 countries have adopted laws that criminalize HIV transmission, while prosecutions for non-disclosure, exposure and transmissions have been recorded in at least 49 countries [3]. These laws are being adopted in a context of rapid expansion of HIV testing of pregnant women through PMTCT programmes. In West and Central Africa, laws criminalize women who transmit HIV to the foetus or child. This puts women in an impossible quandary, given that many are unable to demand condom use or disclose their HIV status due to fears of violence or abandonment by their partners [79]. Data show that punitive laws and law enforcement practices related to sex work and injecting drug use also contribute to stigma, violence and other rights violations against women living with HIV from key populations [3,79].

HIV policies have often failed to take into account gender inequalities in ways that further contribute to discrimination against women. Such policies have also failed to address the reasons behind men's lower access to HIV services. For example, HIV testing and counselling and disclosure has a distinct gendered pattern and dimension [44,45,80]. In a number of countries, more women are tested and know their HIV status compared to men, particularly in the context of women's higher frequency of use of maternal and child health services [81]. Studies from sub-Saharan Africa show that masculine norms and stigma prevent men from seeking HIV testing services [82,83]. Men use their partners' HIV status as a proxy for their own [45]. At the same time, an increasing number of countries are putting in place partner notification policies [45]. Hence, the onus of disclosure is on women, even as it brings with it the risk of violence and other negative consequences.

A number of countries with the highest burden of HIV among women and children have started to implement lifelong ART (Option B +) for all pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV and their infants [81]. The public health rationale and benefits for implementing Option B+ have been well established [84]. However, there is less consideration of the implications of early initiation and lifelong treatment, regardless of CD4+ count, on women that takes into account the gendered realities of their daily lives [85]. Data from Malawi, South Africa and Tanzania suggest that, while women are motivated to initiate and adhere to ART during pregnancy and post-partum periods in order to prevent HIV transmission to their child, they are less motivated to continue thereafter [86–88]. Qualitative data from Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda suggest that women living with HIV appreciate the positive benefits of Option B+, including the ability to prevent transmission to their children and partners, their own improved health and reduced stigma. However, they raise concerns about treatment and adherence in relation to the following: the lack of food security and nutrition that is required to maintain treatment; the requirement to disclose their HIV status, especially for those who face or fear partner violence; lack of information, support and counselling; and the side effects of treatment [87,89].

Conclusions

Addressing gender inequalities is central to improving the sexual and reproductive health outcomes and more broadly, the wellbeing of women living with HIV. Even as HIV prevention, treatment and care services for women living with HIV are being expanded and bringing many benefits, the context of gender inequalities is undermining these efforts. Figure 1 summarizes the pathways by which gender inequalities shape the sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing of women living with HIV.

Figure 1.

Pathways explaining how gender inequalities shape the sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing of women living with HIV.

This paper highlights the importance of interventions for women living with HIV to promote egalitarian and non-violent norms along with equitable decision-making between women and men. It also highlights the importance of interventions to address economic inequalities that contribute to food insecurity, such as interventions that promote land, property and inheritance rights of women living with HIV. Stigma and discrimination, particularly in healthcare settings, needs to be addressed in order to support the reproductive choices of women living with HIV. Strong advocacy is needed to repeal laws that criminalize HIV transmission. Finally, it is not enough to design HIV policies from a narrow biomedical/clinical and health systems framework. Instead, policies must take into account the social and structural context of women's lives from the very inception, so that women living with HIV feel less isolated and are more empowered to make informed choices and decisions with respect to their health and wellbeing. The evidence for effective women-centred approaches is limited. One such example is a study to improve the sexual and reproductive health of Canadian women living with HIV. As part of this study, a framework was developed to identify the elements of a women-centred model of care that addresses their physical health needs (i.e. from a clinical and biomedical perspective) as well as their social, emotional, mental, spiritual and cultural needs more broadly. The framework considers gender along with other intersecting social inequalities. It highlights the needs of women living with HIV for safety, respect, acceptance, self-determination, access to social and other supportive services, tailored and culturally sensitive information, and peer support, among others [90]. While this model is being empirically tested in one setting, it needs to be further applied in low- and middle-income country settings. A more holistic social science research agenda is needed to provide women-centred services to women living with HIV and promote their sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing – one that is grounded in social justice and human rights.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests.

Author's contribution

AA prepared the draft.

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Author information

Avni Amin is a technical officer for violence against women at the WHO. She has worked on issues of gender equality, violence against women and their linkages to sexual and reproductive health and HIV for the last 18 years.

References

- 1.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamutz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint United Nations HIV/AIDS Programme (UNAIDS) The gap report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations HIV/AIDS Programme (UNAIDS) Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCoy SI, Buzdugan R, Ralph LJ, Mushavi A, Mahomva A, Hakobyan A, et al. Unmet need for family planning, contraceptive failure and unintended pregnancy among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melaku YA, Zeleke EG. Contraceptive utilization and associated factors among HIV positive women on chronic follow up care in Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren CE, Abuya T, Askew I, Integra Initiative Family planning practices and pregnancy intentions among HIV-positive and HIV-negative postpartum women in Swaziland: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kikuchi K, Wakasugi N, Poudel KC, Sakisaka K, Jimba M. High rate of unintended pregnancies after knowing of HIV infection among HIV positive women under antiretroviral treatment in Kigali, Rwanda. Biosci Trends. 2011;5(6):255–63. doi: 10.5582/bst.2011.v5.6.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loutfy M, Raboud J, Wong J, Yudin M, Diong C, Blitz S, et al. High prevalence of unintended pregnancies in HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective study. HIV Med. 2012;13(2):107–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvert C, Ronsmans C. The contribution of HIV to pregnancy-related mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2013;27:1631–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fd940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaba B, Calvert C, Marston M, Isingo R, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Lutalo T, et al. Effect of HIV infection on pregnancy-related mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: secondary analyses of pooled community-based data from the network for analysing longitudinal population-based HIV/AIDS data on Africa (ALPHA) Lancet. 2013;381:1763–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60803-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denslow SA, Rositch AF, Fimhaber C, Ting J, Smith JS. Incidence and progression of cervical lesions in women with HIV: a systematic global review. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(3):163–77. doi: 10.1177/0956462413491735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendall T, Barnighausen T, Fawzi WW, Langer A. Towards comprehensive women's health care in sub-Saharan Africa: addressing intersections between HIV, reproductive and maternal health. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(Suppl):S169–72. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdool Karim Q, Banegura A, Cahn P, Christie C, Dintruff R, Distel M, et al. Asking the right questions: developing evidence-based strategies for treating HIV in women and children. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:388. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loutfy MR, Sherr L, Sonnenberg-Schwan U, Walmsley SL, Johnson M, d'Arminio Monforte A, et al. Caring for women living with HIV: gaps in evidence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18509. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18509. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.16.1.18509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruskin S, Ferguson L, O'Malley J. Ensuring sexual and reproductive health for people living with HIV: an overview of key human rights, policy and health systems issues. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15(Suppl 29):4–26. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghanotakis E, Peacock D, Wilcher R. The importance of addressing gender inequality in efforts to end vertical transmission of HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl 2):17385. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.4.17385. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.15.4.17385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orza L, Welbourn A, Bewley S, Tyler Crone E, Vasquez MJ. Building a safe house on firm ground: key findings from a global values and preferences survey regarding the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of women living with HIV. London: Salamander Trust; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.UN General Assembly. Political declaration on HIV and AIDS: intensifying our efforts to eliminate HIV and AIDS. A/RES/65/277. New York: UN General Assembly; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crone ET, Gibbs A, Willan S. From talk to action: review of women, girls and gender equality in national strategic plans for HIV and AIDS in southern and eastern Africa. Durban, South Africa: HEARD; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunkle KL, Decker M. Gender-based violence and HIV: reviewing the evidence for links and causal pathways in the general population and high-risk groups. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):20–6. doi: 10.1111/aji.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. 16 ideas for addressing violence against women in the context of the HIV epidemic: a programming tool. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyegombe N, Abramsky T, Devries KM, Starmann E, Michau L, Nakuti J, et al. The impact of SASA!, a comunity mobilization intervention on reported HIV-related risk behaviours and relationship dynamics in Kampala, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19232. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19232. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle KL, Puren A, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:7666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, Morison LA, Phetla G, Watts C, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomized trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1973–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagman JA, Gray RH, Campbell JC, Thoma M, Ndyanabo A, Ssekasanvu J, et al. Effectiveness of an integrated intimate partner violence and HIV prevention intervention in Rakai, Uganda: analysis of an intervention in an existing cluster randomised cohort. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(1):e23–33. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70344-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senarath U, Gunawardena NS. Women's autonomy in decision making for health care in South Asia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2009;21(2):137–43. doi: 10.1177/1010539509331590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atteraya MS, Kimm H, Song IH. Women's autonomy in negotiating safer sex to prevent HIV: findings from the 20 11 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(1):1–12. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E, Singh S, Hodges Z, Patel D, et al. Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1706–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sofolahan Y, Airhjhenbuwa CO. Cultural expectations and reproductive desires: experiences of South African women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA) Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(3–4):263–80. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.721415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawale P, Mindry D, Stramotas S, Chiliko P, Phoya A, Henry K, et al. Factors associated with desire for children among HIV-infected women and men: a quantitative and qualitative analysis from Malawi and implications for delivery of safer conception counselling. AIDS Care. 2014;26(6):769–76. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.855294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ketchen B, Armistead L, Cook SL. HIV infection, stressful life events, and intimate relationship power: the moderating role of community resources for black South African women. Women Health. 2009;49(2–3):197–214. doi: 10.1080/03630240902963648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatcher AM, Woollet N, Pallitto CC, Mokoatle K, Stoeckl H, MacPhail C, et al. Bidirectional links between HIV and intimate partner violence in pregnancy: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19233. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19233. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wanvenze RK, Wagner GJ, Tumwesigye NM, Nannyonga M, Wabiwire-Mangen F, Kamya MR. Fertility and contraceptive decision-making and support for HIV infected individuals: client and provider experiences and perceptions at two HIV clinics in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nattabi B, Li J, Thompson SC, Orach CG, Earnest J. A systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for policy and service delivery. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):949–68. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keogh SC, Urassa M, Roura M, Kumogola Y, Kalongoji S, Kimaro D, et al. The impact of antenatal HIV diagnosis on postpartum childbearing desires in northern Tanzania: a mixed methods study. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20(Suppl 39):39–49. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shannon K, Leiter K, Phaladze N, Hlanze Z, Tsai AC, Heisler M, et al. Gender inequity norms are associated with increased male-perpetrated rape and sexual risks for HIV infection in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fladseth K, Gafos M, Newell ML, McGrath N. The impact of gender norms on condom use among HIV-positive adults in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):0122671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fulu E, Jewkes R, Roselli T, Garcia-Moreno C, UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence Research Team Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: findings from the UN Multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(4):e187–207. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization (WHO), London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, South African Medical Research Council. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1240937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pantalone DW, Rood BA, Morris BW, Simoni JM. A systematic review of the frequency and correlates of partner abuse in HIV-infected women and men who partner with men. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(Suppl 1):S15–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obermeyer CM, Baijal P, Pegurri E. Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: a review. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1011–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bott S, Obermeyer C. The social and gender context of HIV disclosure in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of policies and practices. SAHARA J. 2013;10(Suppl 1):S5–16. doi: 10.1080/02664763.2012.755319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(4):299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gari T, Habte D, Markos E. HIV positive status disclosure among women attending ART clinic at Hawassa University Referral Hospital, South Ethiopia. East Afr J Public Health. 2010;7(1):151–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Babashani M, Galadanci HS. Domestic violence among women living with HIV/AIDS in Kano, Northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15(3):41–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, Leserman J, Swartz M, Stangl D, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: the importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(6):418–28. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, et al. Overload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. Pyschosom Med. 2009;71(9):920–6. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bfe8d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schafer KR, Brant J, Gupta S, Thorpe J, Winstead-Derlega C, Pinkerton R, et al. Intimate partner violence: a predictor of worse HIV outcomes and engagement in care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(6):356–65. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez EJ, Jones DL, Villar-Loubet OM, Arheart KL, Weiss SM. Violence, coping, and consistent medication adherence in HIV-positive couples. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22:61–8. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trimble DD, Nava A, McFarlane J. Intimate partner violence and antiretroviral adherence among women receiving care in an urban Southeastern Texas HIV clinic. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24:331–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anema A, Vogenthaler N, Frongillo EA, Kadiyala S, Weiser SD. Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: current knowledge, gaps and research priorities. Curr HIV AIDS Rep. 2009;6:224–31. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0030-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiser SD, Tuller DM, Frongillo EA, Senkungu J, Mukiibi N, et al. Food insecurity as a barrier to sustained antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCoy S, Buzdugan R, Mushavi A, Mahomva A, Cowan FM, Padian NS. Food insecurity is a barrier to prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission services in Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:420. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1764-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu T, Zwicker L, Kwena Z, Bukusi E, Mwaura-Muiru E, Dworkin SL. Assessing barriers and facilitators of implementing an integrated HIV prevention and property rights program in western Kenya. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25(2):151–63. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swaminathan H, Bhatla N, Chakraborty S. Women's property rights as an AIDS response: emerging perspectives from South Asia. Washington, DC: ICRW; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swaminathan H, Rugadya M, Walker C. Women's property rights, HIV and AIDS and domestic violence: research findings from two districts in South Africa and Uganda. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strickland RS. To have and to hold: women's property and inheritance rights in the context of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: ICRW; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiser SD, Leiter K, Bangsberg DR, Butler LM, Percy-deKorte F, et al. Food insufficiency is associated with high-risk sexual behaviour among women in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS One. 2007;4(10):260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller CL, Bangsberg DR, Tuller DM, Senkugu J, Kawuma A, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity and sexual risk in an HIV endemic community in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1512–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9693-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deribe K, Woldemichael K, Njau BJ, Yakob B, Biadgilign S, Amberbir A. Gender differences regarding barriers and motivators of HIV status disclosure among HIV-positive service users. SAHARA J. 2010;7(1):30–9. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2010.9724953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Visser MJ, Neufeld S, de Villiers A, Makin JD, Forsyth BW. To tell or not to tell: South African women's disclosure of HIV status during pregnancy. AIDS Care. 2008;20(9):1138–45. doi: 10.1080/09540120701842779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Addo AA, Marquis GS, Lartey AA, Perez-Escamilla R, Mazur RE, Harding KB. Food insecurity and perceived stress but not HIV infection are independently associated with lower energy intakes among lactating Ghanain women. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7(1):80–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levy JM, Webb AL, Sellen DW. “On our own we can't manage”: experiences of infant feeding recommendations among Malawian mothers living with HIV. Int Breastfeed J. 2010;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.West BS, Hirsch JS, El Sadr W. HIV and H2O: tracing the connections between gender, water and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1675–82. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malave S, Ramakrishna J, Heylen E, Bharat S, Ekstrand ML. Differences in testing, stigma and perceived consequences of stigmatization among heterosexual men and women living with HIV in Bengaluru, India. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):396–403. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.819409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Geary C, Parker W, Rogers S, Haney E, Njihia C, Haile A, et al. Gender differences in HIV disclosure, stigma, and perceptions of health. AIDS Care. 2014;26(11):1419–25. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.921278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Visser M. Women, HIV and stigma. Future Virol. 2012;7(6):529–32. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Closson EF, Mimiaga MJ, Sherman SG, Tangmunkongyorakul A, Friedman RK, Limbada M, et al. Intimacy versus isolation: a qualitative study of sexual practices among sexually active HIV-infected patients in HIV care in Brazil, Thailand and Zambia. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brody LR, Stokes LR, Dale SK, Kelso GA, Cruise RC, Weber KM, et al. Gender roles and mental health in women with and at risk for HIV. Psychol Women Q. 2014;38(3):311–26. doi: 10.1177/0361684314525579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacCarthy S, Rasanathan JJ, Ferguson L, Gruskin S. The pregnancy decisions of HIV-positive women: the state of knowledge and way forward. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20(Suppl 39):119–40. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievment of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: a review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2528–39. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kawale P, Mindry D, Phoya A, Jansen P, Hoffman RM. Provider attitudes about childbearing and knowledge of safer conception at two HIV clinics in Malawi. Reprod Health. 2015;12:17. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) Piecing it together for women and girls: the gender dimensions of stigma and discrimination. London: IPPF; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kendall T, Albert C. Experiences of coercion to sterilize and forced sterilization among women living with HIV in Latin America. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):19462. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19462. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.1.19462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.UNDP HIV/AIDS Group. Global commission on HIV and the law: risk, rights and health. New York: UNDP; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maman S, Medley A. Gender dimensions of HIV status disclosure to sexual partners: rates, barriers and outcomes. A review paper. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 81.World Health Organization (WHO) Global update on the health sector response to HIV, 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Skovdal M, Campbell C, Madanhire C, Mupambireyi Z, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. Masculinity as a barrier to men's use of HIV services in Zimbabwe. Glob Health. 2011;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nattrass N. Gender and access to antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. Fem Econ. 2008;14:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ahmed S, Kim MH, Abrams EJ. Risks and benefits of lifelong antiretroviral treatment for pregnant and breastfeeding women: a review of the evidence for the Option B+ approach. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8(5):474–89. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328363a8f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Colvin CJ, Konopka S, Chalker JC, Jonas E, Albertini J, Amzel A, et al. A systematic review of health system barriers and enablers for antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e108150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kamuyango AA, Hirschhorn LR, Wang W, Jansen P, Hoffman RM. One-year outcomes of women started on antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy before and after the implementation of Option B+ in Malawi: a retrospective chart review. World J AIDS. 2014;4(3):332–7. doi: 10.4236/wja.2014.43039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ngarina M, Tarimo EA, Naburi H, Kilewo C, Mwanyika-Sando M, Chalamilla G, et al. Women's preferences regarding infant or maternal antiretroviral prophylaxis for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV during breastfeeding and their views on Option B+ in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clouse K, Schwartz S, Van Rie A, Bassett J, Yende N, Pettifor A. What they wanted was to give birth, nothing else: barriers to retention in option B+ HIV care among postpartum women in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(1):e12–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Webb R, Cullel M. Understanding the perspectives and/or experiences of women living with HIV regarding. Option B+ in Uganda and Malawi. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: GNP+; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carter AJ, Bourgeois S, O'Brien N, Abelsohn K, Tharao W, Greene S, et al. Women-specific HIV/AIDS services: identifying and defining the components of holistic service delivery for women living with HIV/AIDS. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:17433. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.17433. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.16.1.17433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]