Abstract

Veterans underutilize mental health services. We investigated the association between treatment seeking stigma and utilization of mental health services in a sample of 812 young adult veterans. Higher perceived public stigma of treatment seeking was significantly related to lower treatment utilization. Although many veterans were concerned about negative perceptions if they were to seek treatment, a much smaller number of them endorsed that they would judge a fellow veteran negatively in similar situation. Targeting perceived public stigma of treatment seeking, through perceived norms interventions, might help in narrowing the gap between the need and receipt of help among veterans.

Keywords: public stigma, perceived public stigma, barriers to treatment, military culture, mental health treatment seeking, veterans, barriers to treatment, mental health problems, normative misperceptions, mental health treatment utilization

Help Seeking Stigma and Mental Health Treatment Seeking among Young Adult Veterans

Between 19 and 44% of veterans returning from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan meet criteria for mental health disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, or depressive disorders (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Kim, Thomas, Wilk, Castro, & Hoge, 2010; Schell & Marshall, 2008; Seal et al., 2007, 2009). Indeed, rates of mental health problems among veterans are significantly higher than those in the general United States (U.S.) population (Zinzow, Britt, McFadden, Burnette, & Gillispie, 2012). Despite great need for mental health treatment, services are underutilized by recent veterans (Bagalman, 2013; Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Hoge et al., 2004; Kehle et al., 2010; Pietrzak, Johnson, Goldstein, Malley, & Southwick, 2009; Schell & Marshall, 2008). Specifically, surveys indicate that approximately 50% of recent veterans with significant symptoms have not sought services. Thus, a substantial need exists to identify and overcome barriers to receipt of mental health services for veterans in need.

Numerous structural (e.g., accessibility and affordability of mental health services, social support for mental health treatment seeking) and individual factors (e.g., personal beliefs about treatment seeking and treatment effectiveness) interfere with mental health treatment participation (see Barker et al., 2005, for review). Many barriers are similar to those found in civilian samples. Yet, veterans and active duty service members may experience somewhat unique barriers. These include negative attitudes towards seeking help in general (Britt et al., 2008), concerns about confidentiality (Sayer et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2009), desire to handle these problems themselves (Hoge et al., 2004), and lack of confidence in treatment effectiveness (Sayer et al., 2009). Concern about the judgments of others is among the most often mentioned reasons for not seeking treatment in military samples (Britt et al., 2008; Hoge et al., 2004). This particular barrier embodies the notion of stigma and has been noted as an important barrier to seeking treatment among both veterans and the general population (Corrigan, 2004; Zinzow et al., 2012).

Stigma as a Barrier to Care

Researchers have posited several types of stigma, including public stigma and perceived public stigma of relevance to seeking care for mental health problems. Public stigma refers to the endorsement by the public of prejudice against a specific stigmatized group, which manifests in discrimination towards individuals belonging to that group (i.e., viewing individuals with mental health problems as dangerous, unpredictable, and responsible for their condition; Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan & Watson, 2002). Perceived public stigma refers to one’s perceptions regarding the extent to which the public holds negative stereotypes regarding the stigmatized group, i.e., individuals with mental illness (Link, Struening, Rahav, Phelan, & Nuttbrock, 1997). For example, some persons may believe that individuals with mental health problems are dangerous, unpredictable, and personally responsible for their condition. Hence, while public stigma is represented by societal prejudices of persons with mental illness as dangerous and unreliable, perceived public stigma is reflected by the extent to which such prejudiced views are regarded as prevalent in society.

Both the Attribution Theory (AT; Weiner et al., 1985) and Modified Labeling Theory (MLT; Link et al., 1989) provide theoretical frameworks for understanding the roles of perceived public stigma and public stigma in affecting the help seeking behavior of military veterans. According to the AT (Weiner et al., 1985), to make sense of everyday events, people assign different attributes to individuals to explain current and anticipate future behavior. A commonly-held attribution assigned to individuals with mental health problems is that they are dangerous and responsible for their own problems (Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006; Brockington et al., 1993; Farina, 1998; and Taylor & Dear, 1980). Such attributes, when widely disseminated, form the basis for public stigma.

According to the MLT (Link et al., 1989), individuals become aware of stigmatizing beliefs toward individuals with mental health problems early in life as part of cultural socialization. Although not all individuals hold negative stereotypes toward those with mental problems and mere awareness of negative stereotypes is not tantamount to ascribing to them(Crocker & Major, 1989), awareness of public stigma leads to development of expectations as to whether most people will negatively judge someone struggling with mental health problems (Link et al., 1989; Link & Phelan, 2001). Such expectations of rejection and/or discrimination represent the construct of perceived public stigma. Hence, to avoid being labelled as mentally ill and risk potential rejection from others, individuals with mental illness may avoid seeking treatment (Corrigan, 2004).

Evidence suggests that the general public holds negative views of persons with mental illness (Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006). However, findings are mixed regarding the impact of public stigma on actual treatment seeking, with the majority of the reports supporting public stigma as a barrier (Aromaa, Tolvanen, Tuulari, & Wahlbeck, 2011; Cooper, Corrigan, & Watson, 2003; Nadeem et al., 2007; Schomerus, Matschinger, & Angermeyer, 2009) whereas contrary findings have also been observed (Jorm et al., 2000; Ng et al., 2008). Regarding the role of perceived public stigma towards mental illness, we did not find support in the extant literature for significant relationship between this type of stigma and either willingness to seek treatment (Brown et al., 2010; Golberstein, Eisenberg, & Gollust, 2008; Schomerus et al., 2009), or treatment seeking/involvement (Brown et al., 2010; Golberstein et al., 2008; Komiti, Judd, & Jackson, 2006; Rüsch et al., 2009). Hence, based on civilian samples, there is preliminary support for public stigma towards mental illness as a barrier to treatment seeking, and lack of similar support for perceived public stigma.

Military Culture and Stigma

Similarly to civilians, veterans may not want to seek help for their mental health problems to avoid anticipated discrimination from others (i.e., perceived public stigma; Ben-Zeev, Corrigan, Britt, & Langford, 2012). Given that service members are expected to be “tough,” to “shut down” their feelings, and to do their best to cope by themselves with negative affect and difficult emotions (Creamer & Forbes, 2004; Forbes et al., 2008; Nash, Silva, & Litz, 2009; Vogt, 2011), concern about being judged by others for seeking help, rather than for having mental health problems as such, may be reflective of military culture that emphasizes self-reliance and toughness. Indeed, this distinction was made by Vogel and colleagues (2006), who defined stigma towards seeking mental health treatment as a belief that an individual seeking mental health treatment is undesirable or socially unacceptable.

Few studies of stigma as a barrier to care have focused on samples of veterans (e.g., Blais & Renshaw, 2013; Britt et al., 2008; 2012; Hoge et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2010, 2011; Pietrzak et al., 2009; Schell & Marshall, 2008). Of studies on veterans, most aggregate responses for veteran and active duty participants in a way that obscures potentially important differences in the barriers faced by members of the two groups. For example, they may lump separated veterans in with those still affiliated with the military through the National Guard or reserve components. Still other studies have focused exclusively on barriers in veterans already receiving care for mental illness (Ouimette et al., 2001; Rosen et al., 2011; Schell et al., 2011; Stecker, Fortney, Hamilton, & Azjen, 2010). In spite of these limitations, there is indirect, cross-sectional evidence for perceived public stigma towards mental health treatment seeking as a barrier to help seeking among military personnel, including veterans (Kim et al., 2010; Britt, 2000; Britt et al., 2008). Still, others reported contrary findings (Kim et al., 2011). However, we are not aware of any studies assessing the relationship between both public or perceived public stigma and actual treatment seeking behavior among veterans.

Therefore, more work is necessary to learn whether stigma is indeed related to treatment seeking in the broader population of separated personnel (i.e., veterans), and if so, which kind(s) of stigma are associated with limited use of treatment. Hence, the purpose of the present study is to examine the relative importance of perceived public stigma and public stigma as barriers to seeking treatment for mental health issues. We are the first to evaluate both stigma constructs in the same study among a sample of recent veterans with significant symptoms of mental health or substance use disorder. We also are the first to adjust for other known predictors of treatment seeking such as gender, ethnicity, age, and symptom severity (Kazis et al., 1998; Le Meyer, Zane, Cho, & Takeuchi, 2009; Nelson, Starkebaum, & Reiber, 2007; Wang, Olfson, Pincus, Wells, & Kessler, 2005) when evaluating effects of stigma.

Based on preliminary support for perceived public stigma as a barrier to treatment among military personnel (Kim et al., 2010; Britt, 2000; Britt et al., 2008), we hypothesize that veterans endorsing higher levels of perceived public stigma towards seeking treatment for mental health problems will be less likely to have sought treatment themselves. In addition, given lack of military personnel/veteran data, due to preliminary support for public stigma as a barrier to treatment among general public (Aromaa et al., 2011; Cooper et al., 2003; Nadeem et al., 2007; Schomerus et al., 2009), we hypothesize that veterans who more strongly endorse public stigma towards individuals seeking treatment for mental health problems, will be less likely to have sought treatment themselves.

Method

Procedure

Data were collected as part of a larger cross-sectional online survey study looking at health and risk behaviors in a general sample of young adult veterans (see Pedersen et al., 2015). The approval of the Institutional Review Board was obtained for this study. Participants were recruited through the social media website Facebook. Ads for an online survey of veterans’ health and risk behaviors were targeted toward young adult veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Eligibility criteria included age between 18 and 34, separation from active duty or guard/reserve service in the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, or Navy, and access to a computer/smartphone with Internet. Following online consent, participants were directed to an online survey which included the constructs mentioned below.

We followed procedures outlined in our own and others’ work recruiting veterans through Facebook (Brief et al., 2013; Kramer et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2015) to ensure that those responding to our survey met eligibility criteria and were not misrepresenting themselves to receive the offered incentive ($20 Amazon gift card) for participation. These methods included allowing only one Facebook login per survey submission, closely examining the data to look for potential false data (e.g., surveys completed in impossible time lengths), and asking questions about branch, rank, and pay grade at discharge to make sure those items matched up consistently. More detail about the sample obtained and the representativeness to the population of young adult veterans can be found in other work (Pedersen et al., 2015).

Participants

Of 2275 individuals who accessed the survey website by clicking on a Facebook ad, 779 reached the survey consent page and then exited their browser without providing data. An additional 216 were screened out due to ineligibility, 57 declined consent, and 200 provided responses that did not enable confirmation of eligibility. Of the remaining 1,023, 812 provided complete data for all target variables and were included in our analyses. Participants in the full analytic sample averaged 28.26 years of age (SD = 3.39) and 87% (N = 710) were male. Racial/ethnic composition was as follows: 70% non-Hispanic White, 19% Hispanic/Latino(a), 3% Black/African-American, and 8% other ethnicities. We also examined a subsample of the full sample, as described below, to look at treatment utilization among those screening positive for at least one of the mental health problems we assessed for in the survey. These 585 participants were similar to the larger sample in terms of demographics: mean age was 28.26 (SD = 3.39), 88% were male, with 68% non-Hispanic White, 20% Hispanic/Latino(a), 3% Black/African-American, and 8% other ethnicities. The sample we collected as part of the larger study was representative of the broader young adult veteran population, based on comparison to available data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey and data from the Department of Defense (Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense, 2015) in terms of age, gender, marital status, education, and income (see Pedersen et al., 2015). However, the sample contained a greater proportion of veterans from the Army and Marines and of Hispanic/Latino(a) ethnicity than would be expected in the larger young adult veteran population, as well as a lower proportion of veterans from the Navy and Air Force and of African-American race than might be expected in the larger young adult veteran population.

Measures

Mental health symptoms

Current symptoms of mental health problems (PTSD, depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder) were assessed with validated screening measures. The Primary Care PTSD Scale (PC-PTSD; Prins et al., 2003) is a 4-item screener for potential PTSD in the past month, with scores ranging from 0 to 4.The Patient Health Questionnaire - 2 item (PHQ-2; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003) is a 2-item screener for depression, with items assessing “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” and “having little interest in doing things” over the past 2 weeks. Response options range from 0 = “not at all” to 3 “nearly every day,” and the measure is scored from 0-6. A score of 2 or higher indicates optimal screener for depression diagnosis. Anxiety was assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006), which assesses 7 symptoms of general anxiety (e.g., worrying, trouble relaxing) over the past 2 weeks. Response options range from 0 = “not at all” to 3 “nearly every day,” and the measure is scored from 0-21, with 10 indicating an optimal screener for GAD diagnosis. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fente, & Grant, 1993) is a 10-item measures used to assess past year symptoms of an alcohol use disorder (AUD). The measure assessed past year quantity/frequency or alcohol consumption and frequency of problems related to alcohol use. Scores on the measure can range from 0 to 40. Lastly, the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R; Adamson et al., 2010) is an 8-item measure used to past 6-month symptoms of a cannabis use disorder (CUD); including frequency of cannabis use and of problems. The measure is scored from 0 to 32. Scores of 8 on the AUDIT and CUDIT are considered indicators of hazardous use and possible alcohol/cannabis dependence. All measures are well established and have been used with military samples in previous work with adequate reliability and validity (Bliese et al., 2008; Bradley et al., 2003; 2004; Britton et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2013). Reliability of the scales was also adequate in the current sample (GAD-7 α = 0.96, PHQ-2 r = 0.82, PC-PTSD α = 0.87, AUDIT α = 0.90, CUDIT α = 0.82).

Stigma about seeking mental health treatment

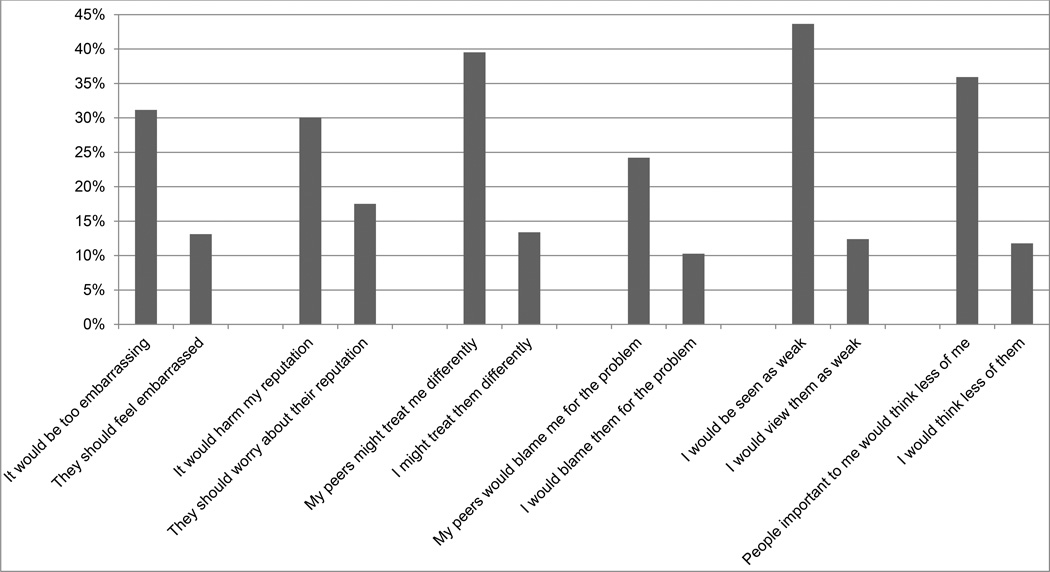

We assessed two forms of stigma: perceived public stigma and public stigma about seeking mental health treatment. These two 6-item scales were modified from the Perceived Stigma and Barriers to Care for Psychological Problems scale, a measure of barriers to care developed for use with young adult service members and college students (Britt et al., 2008; Hoge et al., 2004). The six stigma items from the measure were used verbatim to assess perceived public stigma and we reworded each item slightly to reflect compatible public stigma. For example, an item from the original scale reflected how one believed they would be perceived if he/she sought treatment (“My peers might treat me differently;” perceived public stigma) and was modified to reflect how he/she would view someone seeking treatment to assess public stigma (“I would treat them differently). The 6 pairs of items used in the survey are found in Figure 1. Participants were asked to rate from 1 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree” how each of the items might affect their decision to seek treatment for a psychological problem (e.g., depression, anxiety, or substance use) from a mental health professional (e.g., a psychologist or counselor). For public stigma, participants were asked to consider a gender- and branch-matched young adult veteran who was struggling with a psychological problem and decided to seek treatment. They then rated from 1 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree” how much they agreed with each statement representing negative judgment towards the hypothetical veteran.

Figure 1. Percent of participants agreeing with perceived stigma and public stigma statements.

Note: left statement in pair is perceived stigma item (agreement that statement would affect your decision to seek care for a psychological problem). Right statement in pair is comparable public stigma item (agreement with statement if you knew a [branch and gender-specific] veteran that decided to seek care for a psychological problem).

Treatment receipt

Participants were asked whether since discharge they had ever attended an appointment at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (VA) (including VA hospitals or VA community-based outpatient clinics), a Vet Center, or a non-VA/Vet Center clinic, hospital, or doctor’s office for a mental health concern, such as help with stress, anxiety, depression, or nightmares. They were asked to consider appointments that were not related to service compensation review, which was assessed by another item covering such appointments both mental and physical health concerns. Participants with positive endorsements were asked when their last appointment was, with response options of “over a year ago,” “between 6 months and one year ago,” “between 3 and 6 months ago,” “between one and 3 months ago,” and “within the past month.” These last 4 responses were combined into a single response indicating treatment in the past year.

Data analytic plan

Analyses consisted of univariate descriptive analyses and bivariate correlations with the full sample. These were followed by logistic regression models with only those who screened positive for at least one mental health problem to examine the associations between perceived public stigma and public stigma towards seeking treatment for mental health problems and treatment receipt in the past year. We included only those screening positive for at least one problem in the regression analyses because these represented the participants that likely warranted treatment and would thus be the ones potentially seeking care (i.e., those with probable mental health treatment need).

Regression models for perceived public stigma and public stigma were run separately with outcomes of mental health treatment seeking ever since discharge and in the past year. We chose this analytic strategy for the following reasons. First, there is no literature, which we are aware of, looking at public stigma as well as perceived public stigma and treatment seeking among veterans. Second, the military studies looking at stigma do not control for other known predictors of mental health service use such as symptom severity. Hence, there is inadequate data in the extant literature to recommend either stigma to be entered first, thus, controlling for its’ effects when assessing the effects of the other stigma. Models were run in a sequence as following: age, gender, race/ethnicity, and mental health symptoms were entered in the first step whereupon either perceived public stigma or public stigma was entered in a second. All analyses were run in SPSS version 21.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Table 1 contains the means, frequencies, and bivariate correlations between all predictor and outcome variables for the full sample. Regarding the outcomes, approximately 58% reported having attended at least one appointment for mental health care since discharge from the military; 39% reported past year service use. As expected, service use was positively correlated with severity of mental health symptoms. Perceived public stigma and public stigma were also moderately correlated at r = 0.47. As shown in Figure 1 for the each of the individual stigma item pairs, a higher percentage of participants agreed with perceived public stigma items than they did with public stigma items (e.g., 44% agreed that others would view them as weak if they received treatment, yet only 12% of participants agreed they would view someone who receives treatment as weak).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, frequencies, and correlations of outcome and predictor variables

| Mean (SD) or Frequency | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 28.26 (3.39) | -- | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.007 | −0.11 | −0.16** | −0.12** | −0.07* | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| 2 | Gender | 12.6% | -- | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| 3 | Race/ethnicity | 30.2% | -- | 0.03 | 0.08* | 0.04 | 0.12** | 0.13** | 0.20** | 0.10** | 0.01 | 0.04 | ||

| 4 | GAD-71 | 9.28 (7.06) | -- | 0.86** | 0.63** | 0.37** | 0.21** | 0.13** | 0.32** | 0.49** | 0.44** | |||

| 5 | PHQ-22 | 2.30 (2.13) | -- | 0.56** | 0.35** | 0.23** | 0.16** | 0.31** | 0.45** | 0.42** | ||||

| 6 | PCPTSD3 | 2.31 (1.67) | -- | 0.30** | 0.19** | 0.14** | 0.26** | 0.51** | 0.45** | |||||

| 7 | AUDIT4 | 7.94 (8.01) | -- | 0.34** | 0.32** | 0.31** | 0.23** | 0.21** | ||||||

| 8 | CUDIT5 | 2.41 (5.37) | -- | 0.22** | 0.14** | 0.16** | 0.20** | |||||||

| 9 | Public stigma | 1.48 (0.72) | -- | 0.47** | 0.05 | 0.11** | ||||||||

| 10 | Perceived stigma | 2.07 (0.85) | -- | 0.11** | 0.11** | |||||||||

| 11 | Any mental health care since discharge | 57.6% | -- | 0.74** | ||||||||||

| 12 | Any mental health care past year | 39.1% | -- |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01

Treatment outcomes were coded as 0 = no treatment since discharge/past year and 1 = at least one appointment for mental health treatment since discharge/past year. Race/ethnicity was recoded as 0 = White and 1 = non-White. Gender was coded as 0 = male and 1 = female.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 item scale

Patient Health Questionnaire – 2 item scale

Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder scale

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test –Revised

Seventy-two percent (N = 585) of the sample screened positive for at least one of the mental health problems assessed, with 65% of these participants screening positive for general anxiety, 58% screening positive for depression, 72% screening positive for PTSD, 51% screened positive for hazardous alcohol use, and 17% screened positive for hazardous cannabis use. The following models contained only the participants who screened positive for at least one of the mental health concerns.

Perceived Public Stigma

Mental Health Care Since Discharge

As shown in Table 2 on Step 1, general anxiety, and PTSD were associated with service utilization such that those with more severe symptoms were more likely to have received mental health treatment since discharge. Moreover, on Step 2, perceived public stigma was significantly and negatively associated with service use after adjusting for the impact of age, ethnicity, gender, and mental health symptom severity. Thus, after controlling for other factors, more agreement with perceived public stigma items was associated with less receipt of treatment since discharge. In other words, for each one unit increase in the 4-point stigma scale (e.g., from disagree to agree), we would expect to see a 29% reduction in the odds of receiving treatment since discharge.

Table 2.

Predictors of post-discharge mental health service use

| Mental health service use since discharge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Wald | Exp (B) | 95% CI | ||

| Step 1 (no stigma items) | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 0.06 | 0.03 | 3.75 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.13 |

| Female | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 1.17 | 0.60 | 2.28 |

| Non-White | −0.24 | 0.22 | 1.15 | 0.79 | 0.51 | 1.22 |

| GAD7 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 8.42 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.14 |

| PHQ | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 1.07 | 0.91 | 1.26 |

| PCPTSD | 0.45 | 0.07 | 37.52 | 1.56 | 1.35 | 1.80 |

| AUDIT | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 |

| CUDIT | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 |

| Constant | −3.21 | 0.96 | 11.26 | 0.04 | ||

| Step 2 adding perceived public stigma | ||||||

| Age | 0.05 | 0.03 | 2.59 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 1.12 |

| Female | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 1.22 | 0.62 | 2.39 |

| Non-White | −0.21 | 0.22 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.52 | 1.26 |

| GAD7 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 9.67 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 |

| PHQ | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.28 |

| PCPTSD | 0.47 | 0.07 | 39.53 | 1.59 | 1.38 | 1.84 |

| AUDIT | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.04 |

| CUDIT | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 |

| Perceived public stigma | −0.35 | 0.13 | 6.57 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.92 |

| Constant | −2.44 | 1.00 | 5.97 | 0.09 | ||

| Step 2 adding public stigma | ||||||

| Age | 0.06 | 0.03 | 3.05 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.13 |

| Female | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 1.16 | 0.60 | 2.26 |

| Non-White | −0.18 | 0.23 | 0.63 | 0.84 | 0.54 | 1.30 |

| GAD7 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 8.13 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.14 |

| PHQ | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.71 | 1.07 | 0.91 | 1.27 |

| PCPTSD | 0.46 | 0.07 | 38.60 | 1.58 | 1.37 | 1.82 |

| AUDIT | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.04 |

| CUDIT | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.42 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 |

| Public stigma | −0.25 | 0.15 | 2.72 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 1.05 |

| Constant | −2.80 | 0.99 | 8.00 | 0.06 | ||

Note: significant effects at p < .05 bolded

Mental Health Care in the Past Year

The model for mental health care in the past year is found in Table 3. The first step of the logistic regression model for any mental health care in the past year revealed significant unique effects for general anxiety, PTSD, and CUD, such that those with more severe generalized anxiety, PTSD, and CUD symptoms were more likely to have received mental health treatment in the past year. When we entered perceived public stigma into the model (see Step 2 adding perceived public stigma), significant effects for all control factors remained, but perceived public stigma also displayed a unique effect on past year treatment receipt. More agreement with perceived public stigma items associated with less receipt of treatment. Thus, after controlling for other factors, for a one-unit increase in the perceived public stigma scale, we would expect to see a 26% reduction in the odds of receiving treatment in the past year

Table 3.

Any mental health care utilization in the past year regressed on demographic factors, mental health symptoms, and perceived public stigma and public stigma

| Any use of mental health care past year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Wald | Exp (B) | 95% CI | ||

| Step 1 (no stigma items entered) | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.75 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.10 |

| Female | 0.51 | 0.31 | 2.75 | 1.66 | 0.91 | 3.01 |

| Non-White | −0.05 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.63 | 1.44 |

| GAD7 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 4.31 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.11 |

| PHQ | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.47 | 1.10 | 0.94 | 1.29 |

| PCPTSD | 0.44 | 0.08 | 28.53 | 1.55 | 1.32 | 1.82 |

| AUDIT | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 |

| CUDIT | 0.04 | 0.02 | 6.23 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.08 |

| Constant | −3.62 | 0.94 | 14.93 | 0.03 | ||

| Step 2 adding perceived public stigma | ||||||

| Age | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.09 |

| Female | 0.54 | 0.31 | 3.08 | 1.71 | 0.94 | 3.13 |

| Non-White | −0.01 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.65 | 1.50 |

| GAD7 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 5.22 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.12 |

| PHQ | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.76 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.30 |

| PCPTSD | 0.46 | 0.08 | 30.36 | 1.58 | 1.34 | 1.86 |

| AUDIT | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.03 |

| CUDIT | 0.04 | 0.02 | 6.21 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.08 |

| Perceived stigma | −0.30 | 0.13 | 5.67 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.95 |

| Constant | −2.93 | 0.98 | 8.92 | 0.05 | ||

| Step 2 adding public stigma | ||||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.81 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.11 |

| Female | 0.51 | 0.31 | 2.76 | 1.66 | 0.91 | 3.02 |

| Non-White | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 0.61 | 1.43 |

| GAD7 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 4.34 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.11 |

| PHQ | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.45 | 1.10 | 0.94 | 1.28 |

| PCPTSD | 0.44 | 0.08 | 28.14 | 1.54 | 1.32 | 1.81 |

| AUDIT | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.02 |

| CUDIT | 0.04 | 0.02 | 6.11 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.08 |

| Public stigma | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.37 |

| Constant | −3.69 | 0.97 | 14.43 | 0.03 | ||

Note: significant effects at p < .05 bolded

Public Stigma

Mental Health Care Since Discharge

When we entered public stigma into the model (see Table 2: Step 2 adding public stigma), public stigma was not uniquely associated with mental health care since discharge after controlling for other factors. The significant effects for generalized anxiety and PTSD remained.

Mental Health Care in the Past Year

When we entered public stigma into the model (see Table 3: Step 2 adding public stigma), public stigma was not uniquely associated with past year treatment receipt after controlling for other factors. The significant effects for generalized anxiety, PTSD, and CUD remained.

Discussion

This study examined the impact of public and perceived public stigma on mental health service use by young adult veterans with probable mental health need. A major finding of this study was a discrepancy between participants’ perceptions about possible negative judgments from others and their own beliefs about individuals seeking help. This discrepancy between what someone thinks others would think about their engagement in mental health treatment (e.g., “Others would view me as weak”) and what they themselves actually think about others (“I would not view someone else as weak”) has been demonstrated in college student samples as well (Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein, & Zivin, 2009; Pedersen & Paves, 2014). These results suggest a possible avenue for developing approaches to correct misperceptions of perceived stigma (e.g., “You believe that other veterans would view you as weak if you went in for treatment, yet 88% of veterans report they would not view a fellow veteran that way”).

These results also established that young veterans who screened positive for at least one mental health problem who also endorsed perceived public stigma more strongly were significantly less likely to use mental health services. Still, while perceived public stigma was significantly and inversely associated with treatment participation for those with probable mental health treatment need, participants who endorsed greater severity of mental health symptoms (i.e. general anxiety and PTSD) were more likely to participate in treatment, at any time post-discharge as well as in the past year, despite endorsing perceived public stigma. Interestingly, while neither depression nor alcohol use problem severity were significantly associated with treatment utilization, higher marijuana problem severity was significantly related to higher past year treatment utilization.

To our knowledge, we are the first to assess the relationship between both public and perceived public stigma among young veterans, thus making a significant contribution to the literature. Based on evaluation of stigma as a barrier to actual engagement in treatment among military samples, one prior investigation reported similar results (Kim et al., 2010) while another did not (Kim et al., 2011). The current study differed from this previous research in that we controlled for known predictors of treatment seeking (e.g., demographic factors, mental health symptom severity) and still found that perceived public stigma was inversely related to treatment seeking. Yet, effects for symptom severity were still evident once we considered perceived public stigma. The latter finding suggests that if symptoms are severe enough, veterans may seek treatment regardless of perceived public stigma. However, increased efforts to reduce stigma are likely to reduce stigma-related barriers to treatment seeking and perhaps get early or preventive care that limit the impact these problems can have on individuals and their families in the long-term.

Contrary to hypotheses, we found no significant association between public stigma and help seeking. Specifically, after controlling for relevant variables, public stigma was not significantly associated with treatment utilization since discharge or in the past year. Therefore, veterans’ endorsement of negative judgments towards others seeking care did not seem to have significant impact on their own receipt of services. We also found that mental health symptom severity (i.e. general anxiety, PTSD) was significantly and positively related to treatment utilization both since discharge and in the past year. Similarly degree of marijuana use was significantly associated with treatment utilization in the past year.

Regarding engagement in treatment, close to 60% of our full sample went at least once to an appointment for mental health problems since they were discharged from the military, while close to 40% reported any use of such services in the past year. Though we assessed a different time-frame between discharge and treatment seeking and not all of the participants in our study had mental health need, these findings were similar to the existing reports indicating that approximately 50% of OIF/OEF veterans with mental health problems seek help within one year post discharge (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Schell & Marshall, 2008). Overall, the majority of participants reported little perceived public stigma about anticipated negative judgment from others if they were to seek treatment. For instance, 56% were unconcerned about being perceived as weak. Even so, a substantial percentage (i.e. 44%) anticipated this negative judgment from others. Our results are consistent with reports based on active duty samples (Hoge et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2010; 2011). Thus, evidence indicates that a substantial subset of service members and veterans are concerned about perceived public stigma such as appearing weak if they were to seek mental health care.

Limitations

Although contributing to the literature, our results should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. First, despite many advantages, online data collection is potentially vulnerable to certain shortcomings including participant misrepresentation, concerns about safety and confidentiality. Moreover, online data collection constrains the ability to verify participant eligibility although we took steps to mitigate these potential weaknesses (Kramer et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2015). Second, our measure of perceived public stigma assessed what others, in general, would think and not address beliefs about family and/or friends. Refining assessment of stigma to distinguish beliefs held by the general public from those held by family and friends represents an important area for future stigma work. Finally, the cross sectional nature of our data limits our ability to draw causal inferences, and longitudinal research is required. Specifically, future longitudinal studies are needed to establish the nature of the relationship between perceived public stigma and help seeking.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned limitations, these data contribute to the literature on stigma and help seeking by comparing two different forms of stigma in a large sample of young adult military veterans. Findings were consistent with the possibility that perceptions of public stigma hamper mental health service use in veterans with health care needs. The results also suggest that stigma-related barriers to care may be amenable to change through the use of perceived norms interventions.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant R34AA022400 awarded to Eric R. Pedersen from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors wish to acknowledge the RAND MMIC team and Michael Woodward for assistance with survey development and recruitment.

Contributor Information

Magdalena Kulesza, Associate Behavioral/Social Scientist, RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, Santa Monica, CA 90407., mkulesza@rand.org, phone: 310-393-0411

Eric Pedersen, Behavioral/Social Scientist, RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, Santa Monica, CA 90407., ericp@rand.org, phone: 310-393-0411

Patrick Corrigan, Distinguished Professor of Psychology, Illinois Institute of Technology, 3424 S. State Street, Chicago, IL 60616, Corrigan@iit.edu, phone: 312-567-6751

Grant Marshall, Senior Behavioral Scientist, RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, Santa Monica, CA 90407., grantm@rand.org, phone: 310-393-0411

References

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, Sellman JD. An Improved Brief Measure of Cannabis Misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test – Revised (CUDIT-R) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S. Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: A review of population studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:163–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromaa E, Tolvanen A, Tuulari J, Wahlbeck K. Personal stigma and use of mental health services among people with depression in a general population in Finland. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagalman E. Mental Disorders Among OEF/OIF Veterans Using VA Health Care: Facts and Figures. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Olukoya A, Aggleton P. Young people, social support, and help seeking. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2005;17(4):315–335. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2005.17.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zeev D, Corrigan PW, Britt TW, Langford N. Stigma of mental illness and service use in the military. Journal of Mental Health. 2012;21(3):264–273. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.621468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais RK, Renshaw KD. Stigma and demographic correlates of help-seeking intentions in returning service members. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(1):77–85. doi: 10.1002/jts.21772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, Cabrera O, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Validating the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen and the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist with soldiers returning from combat. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):272–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the alcohol use disorders identification test (audit): Validation in a female veterans affairs patient population. Archives of Internal Medicien. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Kivlahan DR, Zhou XH, Sporleder JL, Epler AJ, et al. Using alcohol screening results and treatment history to assess the severity of at-risk drinking in Veterans Affairs primary care patients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Reseacrh. 2004;28:448–455. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000117836.38108.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brief DJ, Rubin A, Keane TM, Enggasser JL, Roy M, Helmuth E, et al. Web intervention for oef/oif veterans with problem drinking and PTSD symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:890–900. doi: 10.1037/a0033697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt TW. The Stigma of Psychological Problems in a Work Environment: Evidence From the Screening of Service Members Returning From Bosnia1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30(8):1599–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Britt TW, Greene-Shortridge TM, Brink S, Nguyen QB, Rath J, Cox AL, Hoge CW, Castro CA. Perceived stigma and barriers to care for psychological treatment: implications for reactions to stressors in different contexts. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27:317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Britt TW, Wright KM, Moore DW. Leadership as a predictor of stigma and practical barriers toward receiving mental health treatment: A multilevel approach. Psychological Services. 2012;9:26–37. doi: 10.1037/a0026412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton P, Ouimette P, Bossarte R. The effect of depression on the association between military service and life satisfaction. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21(10):1857–1862. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockington I, Hall P, Levings J, Murphy C. The community’s tolerance if mentally ill. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;162:93–99. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote N, Beach S, Battista D, Reynolds CF. Depression stigma, race, and treatment seeking behavior and attitudes. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38(3):350–368. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A, Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Mental illness stigma and care seeking. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:339–340. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000066157.47101.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. How stigma interferes with mental healthcare? American Psychologist. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(1):35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Forbes D. Treatment of PTSD in military and veteran populations. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice and Training. 2004;41:388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.388. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66:522–541. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina A. Stigma. In: Mueser KT, Tarrier N, editors. Handbook of social functioning in schizophrenia. Boston: Allyn & Bakon; 1998. pp. 247–279. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Parslow R, Creamer M, Allen M, McHigh T, Hopwood M. Mechanisms of anger and treatment outcome in combat veterans with PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:142–149. doi: 10.1002/jts.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE. Perceived stigma and mental health care seeking. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:392. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(1023) doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Gotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorn AF, Medwey J, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. Attitudes towards people with depression: effects on the publics’ help seeking and outcome when experiencing common psychiatric symptoms. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;34:612–618. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Milier DR, CJark J, Skinner K, Lee A, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: results from the Veterans Health Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;58:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle SM, Polusny MA, Murdoch M, Erbes CR, Arbisi PA, Thuras P. Early mental health treatment seeking among U. S. National Guard Soldiers deployed to Iraq. Journal of Traumatic Services. 2010;23:33–40. doi: 10.1002/jts.20480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Britt TW, Klocko RP, Riviere LA, Adler AB. Stigma, negative attitudes about treatment and utilization of mental healthcare among soldiers. Military Psychology. 2011;23:65–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2011.534415. [Google Scholar]

- Kim PY, Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Castro CL, Hoge CW. Stigma, barriers to care, and use of mental health services among active duty and National Guard soldiers after combat. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:582–588. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiti A, Judd F, Jackson H. The influence of stigma and attitudes on seeking help from a GP for mental health problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:738–745. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J, Rubin A, Coster W, Helmuth E, Hermos J, Rosenbloom D, Moed R, Dooley M, Kao Y-C, Liljenquist K, Brief D, Enggasser J, Keane T, Roy M, Lachowicz M. Strategies to address participant misrepresentation for eligibility in Web-based research. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2014;23(1):120–129. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 - Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Meyer O, Zane N, Cho Y, Takeuchi DT. Use of specialty mental health services by Asian Americans with psychiatric disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1000–1005. doi: 10.1037/a0017065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A Modified Labeling Theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54(3):400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: Evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S. born Black and Latina women from seeking mental healthcare? Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1547–1554. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash WP, Silva C, Litz B. The historic origins of military and veteran mental health stigma and the stress injury model as a means to reduce it. Psychiatric Annals. 2009;39:789. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KM, Starkebaum GA, Reiber GE. Veterans using and uninsured veterans not using Veterans Affairs (VA) health care. Public Health Reports. 2007;122:93–100. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TP, Jin AZ, Ho R, Chua HC, Fones SC, Lim L. Health Beliefs and help seeking for depression and anxiety disorders among urban Singaporean adults. Psychiatric Services. 2008;1:105–108. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense. [cited 2015 May 4];2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community. 2009–2013 Available from: http://www.militaryonesource.mil/

- Ouimette P, Vogt D, Wade M, Tirone V, Greenbaum MA, Kimerling R, Laffaye C, Fitt JE, Rosen CS. Perceived barriers to care among Veterans Health Administration patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services. 2011;8:212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Helmuth E, Schell TL, Marshall GN, Kurz J, PunKay M. Using Facebook to recruit young adult veterans for online mental health research. JMIR Research Protocols. 2015 doi: 10.2196/resprot.3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Paves AP. Comparing perceived public stigma and personal stigma of mental health treatment seeking in a young adult sample. Psychiatry Research. 2014;219:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM. Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(8):1118–1122. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Cameron RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, Thrailkill A, Gusman FD, Sheikh JI. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Fitt JE, Laffaye C, Norris VA, Kimerling R. Stigma, help-seeking attitudes, and use of psychotherapy in veterans with diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199(11):879–885. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182349ea5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Larson JE, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, Batia K. Self-stigma, group identification, perceived legitimacy of discrimination and mental health service use. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):551–552. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer NA, Friedemann-Schanchez G, Spoont M, Murdoch M, Parker LE, Chiros S. A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2009;72:238–255. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Marshall GN. Survey of individuals previously deployed for OEF/OIF. In: Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, editors. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive Injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND MG-720; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Tanielian TL, Farmer C, Jaycox L, Marshall GN, Vaughan CA, Wrenn G. A needs assessment of New York State veterans final report to the New York State Health Foundation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2011. RAND Health., Rand Corporation., New York State Health Foundation. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. The stigma of psychiatric treatment and help seeking intentions for depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;259:298–306. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0870-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KM, Bertenthal D, Miner CR, Sen S, Marmar C. Bringing the war back home: Mental health disorders among 103 788 U.S. veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of VA facilities. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:476. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KM, Metzer TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Marmar CR. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of VA healthcare 2002–2008. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:1651. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker T, Fortney JC, Hamilton F, Azjen E. An assessment of beliefs about mental healthcare among veterans who served in Iraq. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(1358) doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1980;7:225–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt D. Mental health related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: A review. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:135–142. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PSLM, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review. 1985;92(2):548–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells TS, Horton JL, LeardMann CA, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ. A comparison of the PRIME-MD PHQ-9 and PHQ-8 in a large military prospective study, the Millennium Cohort Study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;148(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KM, Cabrera OA, Bliese PD, Adler AB, Hoge CW, Castro CA. Stigma and barriers to care in soldiers post-combat. Psychological Services. 2009;6:108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0012620. [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Britt TW, McFadden AC, Burnette CM, Gillispie S. Connecting active duty and returning veterans to mental health treatment: Interventions and treatment adaptations that may reduce barriers to care. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:741–753. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]