Abstract

Perceived criticism (PC) is a measure of how much criticism from 1 family member “gets through” to another. PC ratings have been found to predict the course of psychotic disorders, but questions remain regarding whether psychosocial treatment can effectively decrease PC, and whether reductions in PC predict symptom improvement. In a sample of individuals at high risk for psychosis, we examined a) whether Family Focused Therapy for Clinical High-Risk (FFT-CHR), an 18-session intervention that consists of psychoeducation and training in communication and problem solving, brought about greater reductions in perceived maternal criticism, compared to a 3-session family psychoeducational intervention; and b) whether reductions in PC from baseline to 6-month reassessment predicted decreases in subthreshold positive symptoms of psychosis at 12-month follow-up. This study was conducted within a randomized controlled trial across 8 sites. The perceived criticism scale was completed by 90 families prior to treatment and by 41 families at 6-month reassessment. Evaluators, blind to treatment condition, rated subthreshold symptoms of psychosis at baseline, 6- and 12-month assessments. Perceived maternal criticism decreased from pre- to posttreatment for both treatment groups, and this change in criticism predicted decreases in subthreshold positive symptoms at 12-month follow-up. This study offers evidence that participation in structured family treatment is associated with improvement in perceptions of the family environment. Further, a brief measure of perceived criticism may be useful in predicting the future course of attenuated symptoms of psychosis for CHR youth.

Keywords: schizophrenia, expressed emotion, psychosocial treatment, family interaction

Youth who are at risk for conversion to psychosis due to a recent onset of subthreshold psychotic-like symptoms (Miller et al., 2002, 2003) and treatment seeking (Addington, Cornblatt et al., 2011) may benefit from early interventions. Given that the majority of individuals at clinical high risk (CHR) do not go on to psychosis (Addington, Cornblatt et al., 2011), and there are risks including weight gain and metabolic syndrome associated with the use of antipsychotic medications (McGorry et al., 2009), the advancement of psychosocial treatments that enhance protective factors without exacerbating symptoms or heightening risk is essential. CHR individuals can be identified in early adolescence, a time during which they are typically living at home and encountering the daily challenges of family life. Efforts to reduce family risk and enhance family protective factors may be particularly relevant during this developmental phase. Family therapy has been found to reduce positive symptoms for CHR populations (Miklowitz et al., 2014). The focus of the current study is on perceived criticism, a family factor that has been prospectively associated with poor course of illness among patients with schizophrenia (Hooley, 2007; Tompson et al., 1995), depression (Hooley & Teasdale, 1989), substance abuse (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, & Hooley, 2001), anxiety disorders (Renshaw, Chambless, & Steketee, 2003), and at clinical high risk for psychosis (Schlosser et al., 2010).

Many different theoretical approaches provide complementary explanations for why perceived criticism may contribute to poor symptom trajectories. First, engaging in interactions that include critical remarks may be stressful for individuals at risk for psychosis. For example, when individuals with schizophrenia talk with caregivers who are highly critical of them, they demonstrate higher levels of autonomic arousal than do those who talk with caregivers who are low in criticism (Tarrier, Vaughn, Lader, & Leff, 1979; Sturgeon, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Turpin, & Leff, 1981). If emotional arousal is occurring on a daily basis, that may compromise neuroregulatory processes that may increase risk for psychosis (Lukoff, Snyder, Ventura, & Nuechterlein, 1984). There is substantial support for expressed emotion as a predictor of intensification of positive symptoms of psychosis (Kavanagh, 1992), and criticism and hostility appear to be the key constructs that are most strongly related to outcome. Individuals who feel criticized and rejected by parents often defend themselves by distancing from family members (Khaleque & Rohner, 2002). While this strategy may protect individuals from perceived family stress, it may also deprive them of the potential benefits of positive family interactions (Cohen, 2004). Also, it may be quite difficult to distance completely from individuals that have considerable influence over one’s daily life. Moreover, individuals with schizophrenia tend to be rejected by others (Nisenson, Berenbaum, & Good, 2001), which may heighten the importance of the family environment given a lack of alternatives.

In this study we examined whether family interventions designed to alleviate stress and enhance coping, suggest benign attributions for symptoms, and support constructive family engagement were associated with decreases in perceived criticism. It was hypothesized that an 18-session treatment that included explicit training in family communication and problem solving (FFT-CHR) in addition to psychoeducation would be more effective in facilitating reductions in perceived criticism from pretreatment to 6-month reassessment than would a briefer 3-session family psychoeducation intervention (EC). Further, we hypothesized that changes in perceptions of family criticism from baseline to 6 months would predict improvement in subthreshold positive symptoms of psychosis at a 12-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were a subset of those recruited into the second phase of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS2), a consortium of eight research centers (for further information see Addington et al., 2012). Consistent with NAPLS2 criteria, individuals between the ages of 12 and 35 who are primarily English speaking and meet criteria for one of three prodromal syndromes assessed by the Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms (SIPS: Miller et al., 2002) were considered for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included a previous DSM–IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, mental retardation, current drug or alcohol dependence, or the presence of a neurological disorder.

Between January 2009 and February 2012, NAPLS participants who expressed interest in a randomized clinical trial of family therapy were recruited. One hundred twenty-nine CHR youths and their parent(s) or significant others signed informed consent documents and were randomly assigned to an 18-session Family Focused Therapy (FFT-CHR), or to a three session Enhanced Care treatment (EC), using a modification of Efron’s biased coin-toss procedure. Randomizations were stratified by study site and CHR individuals’ use of antipsychotic medication. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating university. For more details and a consort flow diagram, see O’Brien et al., (2014) or Miklowitz et al., (2014).

Psychosocial Treatment Intervention

Detailed treatment manuals guided therapists’ work in each treatment condition (Miklowitz et al., 2010; De Silva et al., 2009), and the same therapists provided both FFT-CHR and EC at each site. Individual family treatment sessions were approximately 50 minutes in both conditions. Therapists who delivered the intervention were primarily doctoral-level with some master’s-level therapists. As part of FFT-CHR approximately six sessions focused on psychoeducation, during which the therapist facilitated discussions of the youths’ symptoms, daily stressors, youth and family coping strategies, a vulnerability-stress perspective, ways of enhancing family support, and the development of prevention action plans. These same topics were addressed in an abbreviated manner during EC, the three-session treatment. As part of FFT-CHR, approximately five sessions were dedicated to communication enhancement, and six sessions were devoted to problem-solving training and integration of communication and problem-solving skills (for more information regarding FFT-CHR and EC see Schlosser et al., 2012).

Treatment sessions were videotaped or audiotaped and rated for therapist fidelity using the Therapy Competence and Adherence Scales Revised (TCAS-R; Weisman et al., 2002; Miklowitz et al., 2008). Ninety percent of treatment sessions were classified as competently done and adherent with no significant difference in overall adherence between treatment groups. By design, FFT-CHR sessions included a significantly greater emphasis on communication and problem-solving skills training than EC sessions, whereas provision of psychoeducation and nonspecific therapist skills such as rapport with patients or pacing of sessions did not differ between conditions (Marvin, Miklowitz, O’Brien, & Cannon, 2014).

Procedures

Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS)

Prodromal symptoms were rated by independent evaluators pre- and posttreatment using the SOPS contained within the SIPS interview (Miller et al., 2002, 2003; Hawkins et al., 2004; Lemos et al., 2006). The SOPS scales range from 0–6 with extensive anchors for each scale point for each symptom. This investigation focused only on the positive SOPS symptom scale, which assesses symptoms related to unusual thought content, suspiciousness, perceptual disturbances/hallucinations, grandiosity, and disorganized communication. Positive symptoms appear to be more strongly correlated with stress (Tessner, Mittal, & Walker, 2011), and change more than negative symptoms with psychosocial interventions (Addington, Epstein et al., 2011; Morrison et al., 2007; Miklowitz et al., 2014). Therefore, this study focuses on positive symptoms as the main outcome variable.

Perceived criticism

Individuals at clinic high risk completed an adaptation of the Perceived Criticism Scale (PCS; Hooley & Teasdale, 1989), which consists of two questions about their mother’s attitude toward them (How critical is your mother of you? How disapproving is your mother of what you do?). Mothers completed the same two questions regarding their criticism and disapproval of their son or daughter (How critical are you of your son/daughter? How disapproving are you of your son/daughter?). Responses were rated on 10-point Likert scales ranging from 0 not at all to 10 very; the ratings of criticism and disapproval were summed to create the perceived criticism variable, with possible scores ranging from 0–20. At baseline, there were significant associations between mother and youth reports of maternal criticism (r(84) = .37, p = .001). A paired-samples t test indicated that youths’ reports (M = 11.27, SD = 4.49) were significantly higher than mothers’ reports (M = 9.64, SD = 3.81); t(83) = −3.18, p = .002. Perceived criticism was measured at baseline and 6-month reassessment. Change scores were calculated by subtracting 6-month reports of criticism from baseline reports of criticism for each reporter.

In a prior study of patients with major depressive disorder, Hooley and Teasdale (1989) found that the test-retest reliability for the original PCS item, “How critical do you think _____ is of you?” was .75 over 20 weeks and the correlation between patients’ PCS ratings of the severity of criticism from relatives and the high/low EE status of these relatives (based on the CFI) was 0.51. The present study was conducted within the context of NAPLS2 that included many time-intensive research evaluations. Reducing subject burden was vital, so we selected a measure of perceived criticism that has established empirical properties, prior utility in predicting symptom change (Renshaw, 2008), and is quite brief.

Statistical Analyses

To test whether there were changes in maternal criticism from pre- to posttreatment, two repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted with treatment group (FFT vs. EC) as the between-subjects factor and time (baseline and 6-month follow-up) as the repeated factor, and maternal criticism as the repeated dependent variable. These ANOVAs were calculated separately for youths’ and mothers’ perceived criticism scores (i.e., youth’s and mother’s reports about the mother’s criticism).

To evaluate the possibility that those who did not participate in the 6-month reassessment were significantly different (i.e., more or less critical, symptomatic, and or different demographically) from those who did participate, t tests or χ2 tests were conducted on youths’ and mothers’ baseline reports of criticism, youths’ SOPS scales, and demographic data with those participating in both baseline and reassessment compared to those participating in just baseline.

Two multiple regression models were computed to evaluate whether changes in maternal criticism from pre- to posttreatment predicted improvement in youths’ subthreshold positive symptoms of psychosis at the 12-month reassessment (PCS scores were not available at 12 months). Change in maternal criticism, SOPS positive symptoms scores assessed at baseline and 6 months, treatment condition (FFT-CHR vs. EC), the interaction of change in criticism and treatment condition, and the use of antipsychotic medications were entered as independent variables, and the 12-month rating of SOPS positive symptoms was entered as the dependent variable. Mothers’ and youths’ perceived criticism scores were entered in separate equations.

Results

Participants

Of the 129 families randomized to treatment, 90 mothers (48 assigned to FFT and 42 assigned to EC), and 90 youths (46 assigned to FFT and 44 assigned to EC) completed the baseline Perceived Criticism scale. Perceived criticism data were collected at 6 months from 43 mothers (48% of baseline participants; 26 assigned to FFT and 17 to EC), and 41 youths (46% of baseline participants; 25 assigned to FFT and 16 to EC). Baseline demographic, clinical, and family assessment information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Sample That Completed the Baseline Perceived Criticism Questionnaire

| Youths’ characteristics | EC (n = 44) | FFT-CHR (n = 46) | χ2 or t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 17.0 (3.1) | 16.7 (3.3) | <1 | .66 |

| Years of education | 10.20 (2.56) | 9.9 (2.34) | <1 | .57 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 59.1% | 58.7% | <1 | .97 |

| Ethnicity | 5.10 | .75 | ||

| African American | 4.5% (n = 2) | 13% (n = 6) | ||

| Asian American | 6.8% (n = 3) | 4.3% (n = 2) | ||

| Caucasian | 61.4% (n = 27) | 54.3% (n = 25) | ||

| Hispanic American | 18.2% (n = 8) | 15.2% (n = 7) | ||

| Multiracial | 6.9% (n = 3) | 8.6% (n = 4) | ||

| Native American | 2.3% (n = 1) | 4.3% (n = 2) | ||

| SOPS Positive Symptoms Scale | 11.63 (3.35) | 11.33 (3.21) | <1 | .68 |

| Antipsychotic medications | <1 | .71 | ||

| Yes | 22.7% | 19.6% | ||

| DSM diagnoses | ||||

| Major depressive disorders | 27.9% (n = 12) | 39.1% (n = 18) | 1.25 | .26 |

| Bipolar disorders | 9.1% (n = 4) | 2.2% (n = 1) | 2.05 | .15 |

| Substance disorders | 2.3% (n = 1) | 6.6% (n = 3) | 1.96 | .58 |

| Anxiety disorders | 54.5% (n = 24) | 52.2% (n = 24) | <1 | .82 |

| Eating disorders | 0% (n = 0) | 2.2% (n = 1) | <1 | .33 |

| Attention deficit disorders | 11.3% (n = 5) | 13% (n = 6) | <1 | .30 |

| Learning disorders | 4.5% (n = 2) | 13% (n = 6) | 2.29 | .32 |

| Developmental disorders | 2.3% (n = 1) | 4.3% (n = 2) | <1 | .58 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) | ||

| Family characteristics | ||||

| Fathers’ age | 48.84 (7.17) | 48.70 (7.95) | <1 | .93 |

| Mothers’ age | 47.34 (7.02) | 44.13 (6.10) | 1.75 | .03 |

| Fathers’ education | 5.57 | .59 | ||

| Primary school | 2.3% (n = 1) | 7% (n = 3) | ||

| Some high school | 29.6% (n = 13) | 32.5% (n = 14) | ||

| Some college | 43.1% (n = 19) | 39.6% (n = 17) | ||

| Some graduate school | 25% (n = 11) | 20.9% (n = 9) | ||

| Mothers’ education | 8.11 | .23 | ||

| Primary school | 0 | 2.2% (n = 1) | ||

| Some high school | 20.5% (n = 9) | 31.1% (n = 14) | ||

| Some college | 61.4% (n = 27) | 51.1% (n = 23) | ||

| Some graduate school | 18.2% (n = 8) | 15.6% (n = 7) |

Note: EC = enhanced care; FFT-CHR = Family Focused Therapy for Clinical High-Risk; SOPS = Scale of Prodromal Symptoms.

Changes in Perceived Criticism From Pre- to Posttreatment

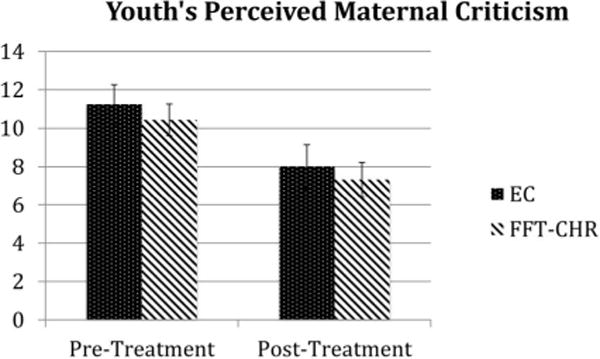

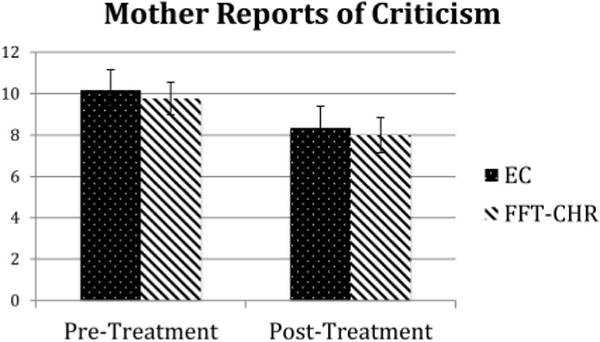

When youths’ perceived maternal criticism was entered as the dependent variable, there was a statistically significant effect of time, F(1, 39) = 21.04, p < .0001, but not of the interaction between time and treatment group, F(1, 39) < 1, p = .93. As presented in Figure 1, youths’ perceived maternal criticism was significantly higher at baseline (M = 10.85; SE = .65) than at follow-up (M = 7.66; SE = .73) for both treatment groups. Similarly, when mothers’ perceived criticism was entered as the dependent variable, there was a statistically significant effect of time, F(1, 41) = 10.52, p = .002, but not of the interaction between time and treatment group, F(1, 41) < 1, p = .96. As presented in Figure 2, mothers’ perceived criticism was significantly higher at baseline (M = 9.97; SE = .63) than at follow-up (M = 8.18; SE = .67) for both treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Mean of youths’ perceived maternal criticism pre- and post- treatment for FFT and EC with standard error bars. EC = enhanced care; FFT-CHR = Family Focused Therapy for Clinical High-Risk.

Figure 2.

Mean of mothers’ perceived criticism pre- and posttreatment for FFT-CHR and EC with standard error bars. EC = enhanced care; FFT-CHR = Family Focused Therapy for Clinical High-Risk.

Are Changes in Perceived Criticism Due to Study Attrition?

Youths’ perceived maternal criticism was not associated with whether or not the youth completed the follow-up visit, t(88) = 1.03; p = .31. Similarly, mothers’ reports of perceived criticism did not differ according to whether the youth participated in the pre- and postassessments, t(88) < 1; p = .58. Thus, changes in levels of criticism over time were not apparently due to attrition of the most critical families from the study. See Table 2 for t tests presented separately for each treatment group.

Table 2.

T-Tests Comparing Perceived Criticism, Symptom Scales, and Demographics Collected Pretreatment for Those Who Did and Did Not Complete Posttreatment Questionnaires

| Completed pre- and posttreatment questionnaires

|

Did not complete posttreatment questionnaires

|

t-test or χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Means (SD) n | Means (SD) n | ||

| FFT-CHR participants | |||

| Perceived criticism | |||

| Youth perception of mother | 10.46 (3.92) 25 | 12.36 (4.90) 21 | t = 1.46, p = .15 |

| Mother perception | 9.77 (3.71) 26 | 9.55 (3.49) 22 | t < 1, p = .83 |

| Age | |||

| Youth | 16.96 (3.86) 25 | 16.41 (2.67) 21 | t < 1, p = .58 |

| Mother | 44.65 (6.37) 26 | 44.62 (6.79) 22 | t < 1, p = .99 |

| Education on 9-point scale | |||

| Mother | 6.77 (1.42) 26 | 6.81 (1.40) 22 | t < 1, p = .92 |

| Youth SOPS baseline symptoms | |||

| Positive Symptom Scale | 11.08 (3.78) 25 | 11.62 (2.48) 21 | t < 1, p = .58 |

| Youth gender male | 59.1% | 58.3% | χ2 < 1, p = .96 |

| Youth antipsychotic medication | 18.2% | 20.8% | χ2 < 1, p = .82 |

| EC participants | |||

| Perceived criticism | |||

| Youth perception of mother | 11.25 (4.42) 16 | 11.18 (4.75) 28 | t < 1, p = .96 |

| Mother perception | 10.18 (4.50) 17 | 9.44 (3.75) 25 | t < 1, p = .57 |

| Age | |||

| Youth | 18.06 (3.69) 16 | 16.39 (2.64) 28 | t = −1.74, p = .09 |

| Mother | 45.41 (6.33) 17 | 48.04 (7.92) 25 | t = 1.14, p = .26 |

| Education on 9-point scale | |||

| Mother | 6.88 (1.50) 17 | 7.00 (1.15) 25 | t < 1, p = .78 |

| Youth SOPS baseline symptoms | |||

| Positive Symptom Scale | 11.31 (3.24) 16 | 11.83 (3.47) 28 | t < 1, p = .64 |

| Youth gender male | 60.7% | 56.3% | χ2 < 1, p = .77 |

| Youth antipsychotic medication | 21.4% | 25% | χ2 < 1, p = .79 |

Note: EC = enhanced care; FFT-CHR = Family Focused Therapy for Clinical High-Risk; SOPS = Scale of Prodromal Symptoms.

Perceived Criticism and Youths’ Positive Symptoms

As shown in Table 3, youths’ reported changes in mothers’ criticism between baseline and 6 months predicted youths’ positive symptoms at 12-month follow-up. Taken together, positive symptoms at baseline and 6 months, changes in youths’ reports of mothers’ criticism, treatment condition (FFT-CHR vs. EC), the interaction of change in criticism and treatment condition, and the use of antipsychotic medications explained 42% of the variance in positive symptoms at 12-month follow-up, F(6, 31) = 2.99, p = .02. Changes in mothers’ reports of criticism did not significantly predict youths’ positive symptoms at 12-month follow-up, though the trend was in the same direction as for youth reports of maternal criticism, β = −.45, t(31) = −1.91, p = .06 (two-tailed).

Table 3.

Summary of Regression Analysis Predicting Subthreshold Positive Symptoms of Psychosis at 12-Month Assessment

| Variable | Standardized coefficients beta | t | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | −.38 | .70 | |

| SOPS Positive Symptom Scale–Baseline | .53 | 2.72 | .01 |

| SOPS Positive Symptom Scale–6 month | .13 | .76 | .45 |

| Youth reported change in perceived maternal criticism | −.46 | −2.33 | .02 |

| Antipsychotic medications | −.25 | −1.19 | .24 |

| Treatment group | −1.87 | −.91 | .37 |

| Change in criticism by treatment group | .27 | 1.09 | .29 |

Note: SOPS = Scale of Prodromal Symptoms.

Discussion

Perceived criticism—the degree to which an individual experiences a significant other as negative and judgmental—has been found to predict the course of psychosis spectrum disorders. In this study, we found that mothers and youths who participated in Family-Focused Therapy and Enhanced Care reported a decrease in mothers’ criticism from pre- to posttreatment and that these decreases predicted improvement in youths’ positive symptoms at 12 months, over and above the improvement in symptoms at 6 months. The improvement in perceived criticism was not due to differential attrition of those mothers who were most critical at baseline.

Given that a decrease in perceptions of maternal criticism was observed in both treatment groups, it is possible that the change is due to spontaneous reductions in criticism that occur with the passage of time or family members’ adjustment to the youths’ symptoms. However, prior research has found that caregivers’ criticism intensifies over time, with family members who have been coping with an ill relative’s symptoms of psychosis for less than a year making significantly fewer critical comments than relatives who have been coping with the illness for 3–5 years (Hooley & Richters, 1995). Family members’ criticisms of an ill relative are associated with attributions of control over symptoms (Hooley & Campbell, 2002). Although the EC condition was considerably shorter than the FFT-CHR condition, both treatments provided psychoeducation about factors that challenge a high-risk person’s ability to control behavior (i.e., genetic factors, neural mechanisms), and utilized a structured approach to decreasing family tension by identifying stressors, broadening coping options, and strengthening family support. Further, both treatments were provided by highly motivated therapists with expertise in working with the clinical high-risk population and supervisory support. Therefore, the psychoeducational aspects of both treatments along with nonspecific factors may have contributed to the decrease in perceived criticism in both groups.

Decreases in youth’s perceived maternal criticism from baseline to 6 months predicted improvement in subthreshold positive symptoms of psychosis at 12 months; decreases in mothers’ perceived criticism were marginally significant predictors (p = .06, two-tailed). Common method variance does not explain the stronger association for youth perceived criticism since change in positive symptoms was based on interviewer reports. These findings are consistent with prior research on schizophrenia suggesting that levels of parental criticism are not as predictive of symptom trajectories as patients’ perceptions of criticism (Tompson et al., 1995; Lebell et al., 1993).

Whereas decreases in perceived maternal criticism may precede and facilitate CHR youths’ symptom improvement, it is also possible that improvement in CHR youths’ positive symptoms (e.g., decreases in suspiciousness and perceptual disturbances) allow them to make more accurate assessments of their mothers’ criticism, as well as provide mothers with fewer behaviors to criticize. Research has found that relatives’ critical remarks decline when patients are less symptomatic (Hooley & Richters, 1995), suggesting that relatives’ critical attitudes are at least in part a response to aspects of patients’ illnesses. Since assessment of mothers’ criticism was conducted at baseline and 6 months only, we cannot determine the causal relation between perceived criticism and symptom outcome. In future research, more frequent assessment of perceived criticism and youths’ symptoms will advance understanding of the sequences of change, which may differ for different families. Findings from the current study that utilizes a brief measure of maternal criticism are encouraging given that more frequent assessment should not create extraordinary subject or experimenter burden.

An important limitation of this study is that only about half of the families that completed family study questionnaires at baseline also completed the 6 month perceived criticism measure. This treatment study was part of the larger NAPLS2 study that required participants to engage in a broad array of assessments (i.e., MRI, psychophysiological, etc.) and therefore subject burden was considerable. While factors such as motivation were not measured, it is possible that only the most enthusiastic and conscientious families completed the study questionnaires, and decreases in perceived criticism in response to these structured family treatments may require those family characteristics.

In our published study utilizing the complete treatment sample, we reported that both treatment groups (FFT-CHR and EC) experienced significant improvement in positive symptoms at 6 months compared to baseline and that the FFT-CHR group improved significantly more than EC (Miklowitz et al., 2014). These findings are maintained at the 12-month follow-up. The present findings suggest that changes in perceived criticism do not explain the differential effects of FFT-CHR on symptomatic outcomes, given that changes in PC occurred in both conditions. This is in contrast to prior findings that changes in family communication behavior during family problem solving were significantly greater for families who participated in FFT compared to EC treatment (O’Brien et al., 2014). It may be that changes in family communication behavior require training in communication and problem solving while changes in family members’ perceptions or attitudes are most influenced by psychoeducation.

The present findings suggest that even a brief three-session family psychoeducational intervention may facilitate improvement in family environments, and that a brief measure of perceived criticism may be useful in predicting the future course of symptoms for CHR youth. Future studies comparing three sessions of family psychoeducation to three sessions of individually based cognitive–behavioral therapy for CHR individuals (Morrison et al., 2007) may clarify whether family intervention is uniquely able to stimulate change in perceived maternal criticism or other family variables that may affect treatment response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Challenge Grant (RC1 MH088546) to Tyrone Cannon and by a gift to the UCLA Foundation from the International Mental Health Research Organization (IMHRO). Development of the treatment manuals was supported by gifts from the Rinaldi, Lindner, and Staglin families. We thank the families who participated in this randomized trial. Therapists on the project included Ayesha Delany Brumsey, Kristin Candan, Sandra De Silva, Isabel Domingues, Michelle Friedman-Yakoobian, Erin Jones, Stephanie Lord, Nora MacQuarrie, Catherine Marshall, Sarah Marvin, Shauna McManus, Silvia Saade, Danielle Schlosser, Shana Smith, Kathernie Tsai, Miguel Villodas, Barbara Walsh, Kanchana Wijesekera, Kristen Woodberry, and Jamie Zinberg. Transcribers and coders were Elizabeth Cabana, Anna Chen, Kelsey Hwang, Zia Kanani, Lynn Leveille, Amber Kincaid, Ashley Kusuma, Grace Lee, Phuong Nguyen, Stefan Nguyen, Christine Sayegh, and Alex Wonnaparhown. Project coordinators included Angie Andaya, Elisa Rodriguez, and Serine Uguryan.

Footnotes

Mary P. O’Brien and Tyrone D. Cannon are now at the Department of Psychology, Yale University.

Contributor Information

Mary P. O’Brien, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine

David J. Miklowitz, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine

Tyrone D. Cannon, Department of Psychiatry and Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles

References

- Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Carnblatt BA, Mathalon DH, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Cannon TD. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS2): Overview and recruitment. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;142:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Cornblatt BA, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Heinssen R. At clinical high risk for psychosis: Outcome for nonconverters. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:800–805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Epstein I, Liu L, French P, Boydell KM, Zipursky RB. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;125:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva S, Zinberg JL, O’Brien MP, Schlosser DA, Miklowitz DJ, Cannon TD. Treatment manual for NAPLS enhanced care condition (EC) Los Angeles, CA: University of California at Los Angeles; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Hooley JM. Relapse among married or cohabiting substance-abusing patients: The role of perceived criticism. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32:787–801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80021-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KA, McGlashan TH, Quinlan D, Miller TJ, Perkins DO, Zipursky RB, Woods SW. Factorial structure of the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;68:339–347. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00053-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM. Expressed emotion and relapse of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:329–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Campbell C. Control and controllability: Beliefs and behaviour in high and low expressed emotion relatives. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1091–1099. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005779. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702005779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Richters JE. Expressed emotion: A developmental perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology. Vol. 6. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1995. pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Teasdale JD. Predictors of relapse in unipolar depressives: Expressed emotion, marital distress, and perceived criticism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:229–235. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.3.229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.98.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ. Recent developments in expressed emotion and schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;160:601–620. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.5.601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.160.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:54–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00054.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lebell MB, Marder SR, Mintz J, Mintz LI, Tompson M, Wirshing W, McKenzie J. Patients’ perceptions of family emotional climate and outcome in schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;162:751–754. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.6.751. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.162.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos S, Vallina O, Fernández P, Ortega JA, García P, Gutiérrez A, Miller T. Predictive validity of the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS) Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría. 2006;34:216–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoff D, Snyder K, Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH. Life events, familial stress, and coping in the developmental course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1984;10:258–292. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.2.258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/10.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin SE, Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, Cannon TD. Family-focused therapy for individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: Treatment fidelity within a multisite randomized trial. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1111/eip.12144. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/eip.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McGorry PD, Nelson B, Amminger GP, Bechdolf A, Francey SM, Berger G, Yung AR. Intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: A review and future directions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70:1206–1212. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04472. http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.08r04472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, Brent DA. Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder: Results of a 2-year randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, Schlosser DA, Addington J, Candan KA, Marshall C, Cannon TD. Family-focused treatment for adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis: Results of a randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:848–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, Schlosser DA, Zinberg JZ, De Silva S, George EL, Cannon TD. Clinician’s treatment manual for family-focused therapy for prodromal youth (FFT-PY) 2010. Unpublished treatment manual. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Ventura J, McFarlane W, Woods SW. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: Predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29:703–715. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Somjee L, Markovich PJ, Stein K, Woods SW. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: Preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:863–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AP, French P, Parker S, Roberts M, Stevens H, Bentall RP, Lewis SW. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:682–687. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbl042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenson LG, Berenbaum H, Good TL. The development of interpersonal relationships in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2001;64:111–125. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.2.111.18618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/psyc.64.2.111.18618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MP, Miklowitz DJ, Candan KA, Marshall C, Domingues I, Walsh BC, Cannon TD. A randomized trial of family focused therapy with populations at clinical high risk for psychosis: Effects on interactional behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:90–101. doi: 10.1037/a0034667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw KD. The predictive, convergent, and discriminant validity of perceived criticism: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw KD, Chambless DL, Steketee G. Perceived criticism predicts severity of anxiety symptoms after behavioral treatment in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic disorder with agoraphobia. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:411–421. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10048. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser DA, Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, De Silva SD, Zinberg JL, Cannon TD. A randomized trial of family focused treatment for adolescents and young adults at risk for psychosis: Study rationale, design and methods. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2012;6:283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00317.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser DA, Zinberg JL, Loewy RL, Casey-Cannon S, O’Brien MP, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Predicting the longitudinal effects of the family environment on prodromal symptoms and functioning in patients at risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;118:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon D, Kuipers L, Berkowitz R, Turpin G, Leff J. Psychophysiological responses of schizophrenic patients to high and low expressed emotion relatives. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1981;138:40–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.1.40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.138.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Vaughn C, Lader MH, Leff JP. Bodily reactions to people and events in schizophrenics. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1979;36:311–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780030077007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780030077007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessner KD, Mittal V, Walker EF. Longitudinal study of stressful life events and daily stressors among adolescents at high risk for psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37:432–441. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp087. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompson MC, Goldstein MJ, Lebell MB, Mintz LI, Marder SR, Mintz J. Schizophrenic patients’ perceptions of their relatives’ attitudes. Psychiatry Research. 1995;57:155–167. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02598-q. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(95)02598-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Tompson MC, Okazaki S, Goldstein MJ, Rea M, Miklowitz DJ. Clinicians’ fidelity to a manual-based family treatment as a predictor of the one-year course of bipolar disorder. Family Process. 2002;41:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.40102000123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.