Abstract

The objective of this qualitative study was to examine how family caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI) describe their quality of life in the context of their caregiving role. Fifty-two caregivers of adults with moderate or severe TBI (n = 31 parents, n= 21 partners/spouses (77% female, Mean age = 57.96 year, range = 34-78 years) were recruited from three data collection sites to participate in focus groups. Thematic content analysis was used to identify two main meta-themes: Caregiver Role Demands and Changes in Person with TBI. Prominent subthemes indicated that caregivers are (a) overburdened with responsibilities, (b) lack personal time and time for self-care, (c) feel that their life is interrupted or lost, (d) grieve the loss of the person with TBI, and (e) endorse anger, guilt, anxiety, and sadness. Caregivers identified a number of service needs. A number of subthemes were perceived differently by partner versus parent caregivers. The day-to-day responsibilities of being a caregiver as well as the changes in the person with the TBI present a variety of challenges and sources of distress for caregivers. Although services that address instrumental as well as emotional needs of caregivers may benefit caregivers in general, the service needs of parent and partner caregivers may differ.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, caregiver, quality of life

Introduction

Caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI) frequently show elevated psychological distress, lower social functioning, and reduced quality of life (Florian, Katz, & Lahav, 1989; Harris, Godfrey, Partridge, & Knight, 2001; Kolakowsky-Hayner, Miner, & Kreutzer, 2001; Kreutzer, Rapport, et al., 2009; Livingston, Brooks, & Bond, 1985; Marsh, Kersel, Havill, & Sleigh, 1998a, 1998b; McPherson, Pentland, & McNaughton, 2000; Perlesz, Kinsella, & Crowe, 2000; Ponsford, Olver, Ponsford, & Nelms, 2003; Ponsford & Schonberger, 2010). Challenges faced by caregivers may differ depending on their relation to the person with TBI; studies suggest that spouse caregivers experience more stress and psychosocial distress than parent caregivers (Perlesz et al., 2000; Verhaeghe, Defloor, & Grypdonck, 2005), though some studies have not found these differences (Livingston et al., 1985; Ponsford et al., 2003).

Although it is well-established that providing care for someone with a TBI exerts negative effects on caregiver well-being and quality of life, we do not have a full understanding of the experiences of caregivers. With a few notable exceptions (Carson, 1993; Chwalisz & Stark-Wroblewski, 1996; Gill, Sander, Robins, Mazzei, & Struchen, 2011; Godwin, Chappell, & Kreutzer, 2014; Hammond, Davis, Whiteside, Philbrick, & Hirsch, 2011; Johnson, 1995; Lefebvre, Cloutier, & Josee Levert, 2008; Rotondi, Sinkule, Balzer, Harris, & Moldovan, 2007), research on caregivers of individuals with TBI has relied on quantitative methods where the outcomes of interest are narrowly defined variables, such as depression or stress. This approach is restricted by a lack of quantitative measures that are specifically designed to assess health related quality of life (HRQOL) in caregivers of individuals with TBI (Thompson, 2009). Therefore, it is uncertain to what extent the existing literature fully captures the complexities and nuances of caregiver experiences.

Qualitative methodology is well-suited to examine the complex lived experiences and perspectives of caregivers of individuals with TBI. In contrast to a quantitative approach where the investigator determines what is important to study (e.g. anxiety, depression), a qualitative approach allows the caregivers to describe and define what is important in their lives. Without qualitative inquiry, important aspects of the impact of caregiving might be overlooked. Whereas quantitative approaches provide the average or “group” perspective in the form of numerical output, a qualitative approach allows researchers to capture the individual’s point-of-view in the form of rich, personal descriptions, or narratives (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000, 2003). Previous qualitative research on TBI caregivers has focused on either parents (Carson, 1993) or partners (Chwalisz & Stark-Wroblewski, 1996), health care and service needs (Rotondi et al., 2007), couples issues such as intimacy and marital adjustment (Gill et al., 2011; Godwin et al., 2014; Hammond et al., 2011), or other well-defined topics such as a single family’s response to TBI (Johnson, 1995) or social reintegration (Lefebvre et al., 2008). To date, no qualitative study has provided a broad examination of both negative and positive impacts of providing care on the lives of caregivers or provided direct comparisons between the caregiver experiences of parents and partners.

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected to develop a patient reported outcome measure of HRQOL in caregivers of individuals with TBI. The primary paper (Carlozzi et al., 2015) presents the data in quantitative form, such as the percent of comments that cover social health, emotional health, and physical health. The primary paper also presents a conceptual framework that guides the development of “item pools” or large groups of candidate items that may be used in the self-report measure of caregiver HRQOL. The main finding of the study was that existing self-report measures do not have adequate content coverage to provide sufficient assessment of HRQOL in caregivers of individuals with TBI; the need for the self-report measure under development was supported by the data (Carlozzi et al., 2015).

The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine how parent and partner caregivers of individuals with moderate or severe TBI describe their quality of life in the context of their caregiving role. Within this broad goal, we were particularly interested in how caregivers describe their day-to-day lived experiences as caregivers and what challenges and positive experiences they perceived. A second goal was to examine similarities and differences between parent and partner caregivers’ perceptions of quality of life. Because this was an exploratory study, no specific study hypotheses were formulated.

Methods

Procedures

A detailed description of study procedures is described in the primary paper (Carlozzi et al., 2015). Prior to initiation of data collection, the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, Kessler Foundation in West Orange, New Jersey, and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, approved all study procedures. Nine focus groups (three at each site; n=8 participants for two groups, n=7 for one group, n=6 for five groups, and n=2 for one group) were co-facilitated by two clinical psychologists (NC, AK) with experience in qualitative data collection. Participants provided informed consent prior to the start of the ninety-minute focus group; sessions were audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim. All groups except one had a mix of parents and partner caregivers. Group facilitators began each group by describing the purpose of the study and presenting group “ground rules” (e.g. maintaining confidentiality within the group, encouraging spontaneous “popcorn-style” participation in the group); this was followed by open-ended questions designed to encourage participants to talk freely about any aspect of quality of life that they felt most pertinent. Facilitators intervened only to redirect the group if they began to talk at length about the quality of life of the person with a TBI, to normalize differences in experiences between group members, or to allow the opportunity for more reticent group members to speak. Toward the end of the group, the facilitators asked more targeted open-ended questions to probe quality of life in specific domains to ensure that a broad range of topics was covered (See Table 1 for focus group questions, taken from focus group guide). Data “saturation,” or the point at which no new information or themes emerged (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), was reached after the fourth focus group; however, more groups were conducted to ensure a more diverse sample in terms of caregiver characteristics and to meet the sampling requirements of the primary study (Carlozzi et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Focus group questions

| Category | Sample Question |

|---|---|

| Introductory Question | “How has being a caregiver affected your quality of life?” |

| Emotions Question | “How has your emotional quality of life changed since you became a caregiver?” |

| Social Question | “How has being a caregiver affected your social life, your relationships?” |

| Physical Question | “How has your physical health changed since you became a caregiver?” |

| Uniqueness of TBI Caregiving Question |

“How do you think being a caregiver of someone with a TBI is unique from other types of caregiving? How does it uniquely affect your quality of life?” |

| Concluding Question | “What other ways has your quality of life changed since becoming a caregiver? Is there anything we missed?” |

Note. The Introductory Question was always asked first and the Concluding Question was always asked last. The order of the other questions varied between the groups.

Participants

Participants were recruited through fliers, local support groups, established research registries, existing research studies or medical record review. Caregivers were at least 18 years old, able to read and understand English, and caring for an individual who was at least one year post a medically documented moderate or severe TBI (sustained at 16 years or older), according to TBI Model Systems (TBIMS) criteria (Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Data Center, 2006).

Data Coding and Analysis

Focus group transcriptions were analyzed using QSR International’s NVivo 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2012). A thematic content analysis was conducted, with the aim of identifying themes or patterns in the text, involving coder interpretation and synthesis of passages (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Catanzaro, 1988; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014). The coding scheme (“codebook”) was inductively generated through an iterative and collaborative process between members of the coding/analysis team. This approach was taken in order to allow the themes to emerge from the data, which is in contrast to a deductive approach where the text is assigned to predetermined codes (Catanzaro, 1988; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Miles et al., 2014). Analysis steps are depicted in Table 2. The first transcript was coded by two primary coders (AK and NC). All other transcripts were coded by a dyad consisting of one primary coder and a secondary coder (AS, TB, RL). The final coding represents the consensus of the coding dyad.

Table 2.

Thematic content data analysis steps.

| 1 | Focus group recordings transcribed verbatim. |

| 2 | Transcriptions entered into NVIVO software for coding/analysis. |

| 3 | Primary coders* read through one entire focus group transcript, line by line. |

| 4 | Primary coders independently generated coding scheme. |

| 5 | Coders used memos to document thoughts and ideas about observed patterns. |

| 6 | Primary coders met to discuss and refine coding scheme; memos (i.e. reflective notes made by a coder on thoughts about emerging concepts, relationships, themes) used to guide discussion. |

| 7 | Primary coders recode first group transcript with refined coding scheme. |

| 8 | Secondary coders read initial draft of codebook and first focus group transcript, line by line, and provided feedback to further refine the coding scheme. |

| 9 | Codebookrevised based on group consensus. |

| 10 | Steps 3-9repeated until all transcripts were coded; codebook revised as needed. |

| 11 | Coders recoded transcripts that were coded with preliminary codebooks. |

| 12 | Finalized set of coded transcripts reviewed by primary coders for completeness and consistency in application of codebook. |

| 13 | NVIVO queries conducted to extract text for each code according to group (parent/partner). |

| 14 | Analysis dyads independently examined each query to identify meta-themes, subthemes, and commonalities or differences between parent and partner caregivers. |

| 15 | Analysis dyads worked together to establish inter-subjective consensus about the meta-themes, subthemes, and commonalities or differences between parent and partner caregivers. |

| 16 | Entire coding team reviewed complete qualitative analysis results to establish group consensus on final data synthesis and conclusions. |

Note. Primary coders (AK, NC) were also the focus group facilitators

Next, a matrix analysis (Averill, 2002; Miles et al., 2014) was conducted to facilitate the examination of how caregiver type (parent/partner) intersected with each code. Using advanced NVIVO query capabilities, reports were generated separately for each code by group (parent/partner). This allowed for the systematic examination of trends, similarities, and differences in the qualitative content of each theme across the two groups. Dyads of coders worked on the matrix analysis for each theme, first independently and then together to establish inter-subjective consensus, with the following goals: 1) explore higher-order meta-themes that describe how codes relate to each other, 2) synthesize the overarching concept for each code, 3) describe commonalities and differences between parents’ and partners’ experiences, and 4) identify exemplary quotes to illustrate the conclusions of the matrix analysis. A researchers’ journal or “audit” was maintained to document all steps of the data analysis process (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Miles et al., 2014).

Results

Group Characteristics

Of the 52 caregivers whose data were used for this study, 31 were parents (8 fathers, 23 mothers) and 21 were partners (4 husbands, 17 wives). Data from three participants, a sibling, a grandparent, and a friend, were not included in these analyses. Additional group characteristics are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic information about caregivers (participants) and the persons with TBI (care recipients)

| Caregiver (N = 52) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | (%) | M (SD) | Min-Max |

| Age (years) | 57.96 (9.54) | 34 - 78 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 42 | 80.8 | ||

| African American | 6 | 11.5 | ||

| Other | 4 | 7.7 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 | 13.5 | ||

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 2 | 3.8 | ||

| High school graduate/GED | 11 | 21.2 | ||

| Some college | 10 | 19.2 | ||

| College degree | 17 | 32.7 | ||

| Advanced degree | 12 | 23.1 | ||

| Duration of caregiving (years) |

6.56 (4.92) | 1 - 26 | ||

| Household Income* | Median = $40,000 - $74,999 | <$5,000 - ≥$100,000 |

||

|

| ||||

| Individual with TBI (N=52) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age | 42.10 (14.34) | 23 - 75 | ||

| Time since injury | ||||

| < 18 months | 3 | 5.8 | ||

| 18 months – 3 years | 10 | 19.2 | ||

| > 3 years | 39 | 75 | ||

| TBI etiology | ||||

| Motor vehicle accident | 38 | 73.1 | ||

| Fall | 5 | 9.6 | ||

| Diving/Other Sport | 2 | 3.8 | ||

| Violence/Assault | 3 | 5.7 | ||

| Other | 4 | 7.7 | ||

Note. dollar amount before taxes

Meta-Themes

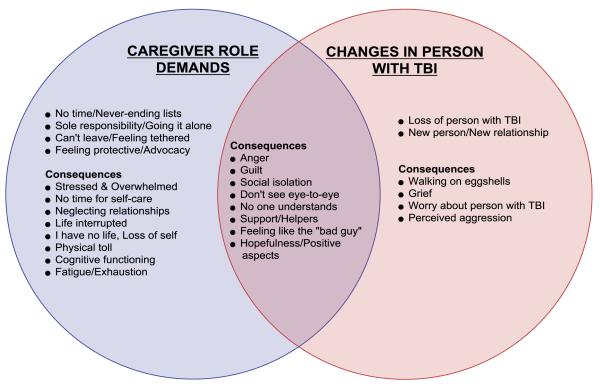

The final codebook consisted of 27 codes that fell under two unifying meta-themes: 1) Caregiver Role Demands, reflecting how new responsibilities post-TBI affect the caregiver; and 2) Changes in the Person with TBI, reflecting how changes in the person with TBI affect the caregiver. Figure 1 depicts a Venn Diagram of codes organized under these meta-themes. Each change was related to a variety of emotional, social, and physical consequences. Most codes were related to one or the other meta-theme, but some codes, such as feeling like the “bad guy” and guilt, overlapped the two meta-themes.

Code Results

The sections below illustrate how the caregiver role and changes in the person with TBI can have a tremendous impact across myriad life domains of caregiver welfare. Although commonalities in caregiver experience were observed for parents and partners, some differences were noted. Illustrative quotations are provided for the most salient and unique codes; some quotes were edited for space. Unedited and additional quotations are included in the Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Caregiver Role Demands

Caregivers reported that the injury resulted in increased demands on time and emotional resources. In many cases, caregivers expressed anger and frustration related to the challenges of managing day-to-day tasks and interactions with medical providers, family and community members, and the person with TBI. They described the caregiving role as coming with never-ending to-do-lists and the feeling that there is not enough time to accomplish everything.

Mother: She became my job, you know, because it’s a 24/7 job…

Wife: You have so much to do and such a short period of time. I just felt like my list never got shorter. I’d mark 3 things off and add 12 to it. I mean, there’s just so much that we have to do.

The sense of not having enough time was compounded by the fact that they often had the feeling of sole-responsibility, like they were “going it alone.” Relative to parents, the accounts of partners reflected more frustration and desperation about having to shoulder all of the work.

Wife: You know, you do everything. I mean EVERYTHING with the big ‘E’.

Wife: I feel like I’m on this constant treadmill 24/7, all the time…I’m tired of being the chauffeur, the cook, the maintenance man, the gardener, the medical supervisor, the scheduler, the laundress, everything! It used to be a shared arrangement and it’s all on my shoulders.

Caregivers often felt they could not leave the person they cared for, like they were figuratively chained or tethered to the person. Caregivers described no longer being able to travel or run errands, feeling like they are stuck and isolated, and wishing they could get away, even for a little while, from the person they care for. When caregivers were able to leave the person they cared for, they described being plagued by worry that something would go wrong. This seemed to be a more salient issue for parents than for partners.

Mother: You’re chained to that person.

Father: You don’t have a social life, and you are restricted. I couldn’t leave to go out to the post office… to run get something at the store. It’s like you’re tied to the house or wherever they are.

Father: You just cannot walk away without having it in the back of your head, “Okay, where are they, what are they doing?” …I’m here now but part of me is still at home because part of me is still worried about my son.

In addition to the more concrete demands on caregivers’ time and resources, they also described a feeling that they needed to be watchful or protective of the person with injury – to help them avoid being taken advantage of, or feel the hurt of social rejection- and in many cases, to serve as their advocate.

Father: So, I feel like I’m just a house cleaner following behind him, trying to smooth things for him.

Wife: I write letters to every single person who tells me no. I stay up all night and I write letters and complaints. I’d like to do advocacy for other people who are not able to do what I’ve done. But, it’s taken my insides out.

Stress was described as a common consequence of the substantial caregiving demands and responsibilities and was often described as overwhelming. Compared to parents, partners talked about stress more in terms of being alone in their duties and decision making. Interestingly, only partners said they felt that the person with the TBI had less stress than they did.

Mother: I say I’m going to die of stress.

Wife: And the physical changes in me, they bother me, because I’m still very young. He has better cholesterol, better pressure. He looks terrific. He has no stress, and he has me as a caregiver. You know, I want me as a caregiver.

Caregivers also described significant lack of personal time and ability to engage in self-care, which often impacted physical, social, and mental health. Caregivers who engaged in self-care noted that incorporating exercise and meditation, getting some “alone time” and seeking professional mental health help were beneficial.

Father: I had a finger that’s messed up, and that happened four years ago and I finally went to the doctor a month ago. Four years. You don’t have time.

Wife: And I just find that my life is consumed with taking care of everybody, and the things that used to nourish me, that I loved to do, I can’t get to.

The caregivers often attributed a number of physical and cognitive problems to stress. These included fatigue/exhaustion, weight loss, autoimmune disease “flare-ups”, teeth grinding/cracked and shifted teeth, irritable bowel syndrome, sleep problems, accelerated aging, and problems with memory, word-finding, focus, and problem solving. Partners more often attributed physical and cognitive problems to stress compared to parents.

Wife: I feel like my husband has a better memory than I do at this point, which is kind of sad to say, someone with a traumatic brain injury can remember more than I can remember. But I definitely think that the stress has had a lot to do with my memory.

Wife: I’m getting an endoscopy on Thursday morning, because I’ve developed something, and it’s the anxiety, and it’s the stress, and it’s the frustration. And it could be gastritis, could be an ulcer. But I feel that it is coming from all of this, carrying this.

Much like for the person with the TBI, the life plans, expectations, and normal developmental milestones are often interrupted for the caregiver after TBI. Prior to the injury, caregivers described anticipated freedom as their children moved out of the house and they moved toward retirement. However, the injury brought about unexpected responsibilities and burdens, loss of income, free-time, and freedom to pursue the life they had planned. Often, caregivers said that it’s as if their life stopped when the injury happened. Much of the discussion focused on interruption of vocational, educational, and financial life trajectories. Fears about the future, such as what the person with TBI would do when the caregiver was unable to provide care, was a more salient life trajectory concern for parents than for partners.

Wife: As you age, you start thinking about retiring, and thinking about, oh, isn’t this wonderful that she [daughter] is going off to college? And now, I’m just thinking about…how worse is she going to get today? It’s things that my counterparts are doing, I’m not doing, so my life is completely different.

Father: I don’t think my parents ever planned their life in terms of what my doctor’s appointments were, right? All of a sudden, it’s a matter of well, when is this doctor appointment? When is this exam going to be? I thought when I was retired I was going to have control of my own schedule…It’s very different from what I was expecting or what I was hoping for.

Father: How do I protect him if I am gone? Who’s going to do that for him? And I don’t want to foist that off on his brother or cousin or something, because they have a life to live…

In many cases, as a result of lack of time and the inability to leave the person with a TBI, the caregiver described having no life or sense of self since the injury.

Mother: I don’t have a life for myself. My life is for my son who’s injured and for my children. After I do for everybody I’m just done for the day. So I, myself, don’t have a life and it’s okay. I want to make sure that he has a life.

Wife: It’s like I’m not a person. If I have a conversation with someone… there’s like – there’s no interaction on my part. And that hurts me, because I was such a mentally active person that – I mean, I had a value.

Changes in Person with TBI

Caregivers cited many ways their loved one has changed since experiencing a TBI, including lack of empathy and awareness of limitations, loss of potential, different personality and lifestyle, and inappropriate behaviors. In the context of the new relationship with this “new” person, parents talked about feeling a return to parenting a much younger child, whereas partners noted a loss of intimacy and shared equality.

Father: Your role as a parent doesn’t change. Yeah, but I didn’t think I’d be the parent of a 28-year old essentially the same way I was the parent of a 17 year old.

Wife: When you’re husband and wife and you have a shared relationship and you have intimacy, and you do things together, and you share decision making and then that person is not there…

For parents, the most salient emotions were grief and sadness about the loss of the person with TBI. Although partners also grieved the loss of the partner they once knew, their accounts reflected more anger and frustration, often related to having to adjust to a “new” spouse.

Mother: What makes it worse is that you are constantly remembering the person they used to be. I tend to cry a lot over that…he still had his whole life ahead of him…and it was just like so tragic.

Wife: I’m married to this man now, not 31 years. I’m married to him almost 9 years. That’s how I look at it now. It’s a new relationship and I have to try to accept things that he does differently that angers me, and not always remember that he never used to do that, you know?

Wife: It’s like living with another person in your marriage. Only the name of that person is TBI. And you kind of have to figure out how you’re going to live – how the three of you are going to live together.

Partners, but not parents talked about how it was difficult to witness changes in the relationship between their spouse and children since the TBI.

Wife: The hardest thing for me is the empathy I feel for my children. You know, in a way, it’s almost harder, what I have to go through, and then it’s magnified in knowing what they miss. Like my daughter’s about to graduate, and he’s not going to be there. And she doesn’t want him there.

Caregivers described worry or nervousness about the person with the TBI suffering another injury, being victimized, or behaving inappropriately in social situations. They also expressed feeling particularly anxious about managing the emotions and behaviors of the person they care for, in terms of being careful about what they say and how much to push them and preventing situations that would be upsetting for them. They often described this as feeling like “walking on eggshells”.

Wife: My husband had a short fuse before, but it’s definitely shorter now, and walking on eggshells, exactly. There’s some times where you’ll be having the nicest time and then all of a sudden, just the littlest thing can just set him off, and you’re kind of sitting back going, wow, who is that person? And then you try to settle him down, and if you say the wrong thing, you know, ‘you’re reminding me of my brain injury’…it’s very hard.

Father: And the anxiety of not knowing when he’s going to do something – he’ll be walking through a department store, and there’s a pretty young lady up there… like an arrow, and you don’t know what he’s going to say. And he gets up close and personal when he shouldn’t. And you can’t stop him before it happens because you don’t know that it’s going to happen, but you can sense it.

Some caregivers perceived verbal and physical aggression from the person with TBI. Wife caregivers often described the aggression as controlling or “domineering” and two wives chose to live apart from the person with TBI due to perceived aggression. Although both parents and partners described dealing with aggression, partners responded to the abuse with more feelings of hurt and distress than did parents.

Mother: The more frustrated he got with his limitations, then he turned on me, shoved up against a wall, you know, in my face like a drill sergeant, and just the anger that came with everything.

Wife: He had a couple of very violent outbursts. I thought for sure he would kill me. You know it just emotionally destroys me just bit by bit eats away at me. He has had a knife in his hand, put some holes in walls, but I think the emotional stress was the thing that I was pretty sure that was going to become so toxic that I would develop some form of cancer probably.

Cross-cutting Codes

A number of themes simultaneously reflected the impact of the caregiving role demands and the changes in the person with TBI. For example, caregivers can be subjected to criticism and blame from others, which can leave a caregiver feeling like they rarely do anything “right.” Caregivers described feeling like “the bad guy” in regard to their decisions about the placement (e.g. living at home) and limit setting for the person with the TBI. Feeling like the “bad guy” may be partly attributed to the fact that caregivers often times do not agree, or “don’t see eye-to-eye,” with others about the abilities or course of care for the person with TBI. Caregivers also described feeling that others do not fully understand the incredible demands of being a caregiver or the changes in the person with the TBI.

Father: I think because you are the caregiver, it’s not your fault, but it’s your fault, you know?.. If anything goes wrong, it’s your fault.

Mother: Seems like you’re constantly having to defend yourself and – they don’t think you’re taking care of them properly.

Both partners and parents described feeling like the person they cared for was angry with and/or blamed them for changes in the relationship; however, the nature of these changes is somewhat different between groups. For parents, children with TBI felt unnecessarily infantilized by the caregiver; however, caregiving had been part of the parent/child relationship before the injury. Partners, on the other hand, were keen to note that the new parent/child dynamic can cause particular stress in a previously more equitable partnership. Additionally, partner accounts of feeling like the “bad guy” reflected more intense conflicts and perceived aggression from the person with a TBI compared to parents.

Wife: Your children get older, and they’re adults, and now you want them to be independent, but you’re still their parent. Whereas with a spouse, I was never a parent before with him. Now I feel like a parent. And that creates tension, because he doesn’t like it.

Husband: I’m the bad guy because I got, just an intense dressing down last night because I wasn’t helping and being supportive enough…You know, it’s the head injury talking, but you’re still getting verbally abused.

Wife: Then he would fight me. So, anytime I wanted to make a change I was the enemy…So after some time he just started to perceive me as being the enemy.

Caregivers described guilt about many things. Parents talked about feeling guilty about being angry with their child with a TBI, not spending enough time or being there for every need of their child, doubting or assuming the worst about their child, and not wanting to include the child in family activities. Parents, but not partners, described feeling guilty and responsible to some degree for their child’s TBI.

Mother: I can’t get angry at him because I think it’s my fault.

Mother: We were gone when NAME got hurt…And my husband, for some reason thought if we were there, it wouldn’t have happened.

Partners mentioned feeling guilt about different things, including enjoying things that their partner could not and feeling that they are enabling their partner’s “bad behavior”. One prominent theme that came up for partners, but not for parents, was guilt related to making decisions alone, including feeling bad about the possibility of making a wrong decision or of cutting their partner out of the decision-making process.

Wife: You do feel guilty, and you think that you’re making the wrong decisions, when you’re talking to the doctors, and they’re saying, well, we want to do this procedure, and what’s your thoughts? And you’re the only person making these life or death decisions. It’s hard when you don’t really have a support person to go to.

Wife: I felt terribly mean, and I went into the bathroom and cried after I said it, but I said, ‘the fellow who doesn’t understand the problem doesn’t get a vote on this.’ And, I thought, that’s the worst thing I’ve said in three years.

Caregivers commonly described social isolation stemming from a lack of time and energy as well as from the social isolation of the person with TBI. Although caregivers in general talked about how the person with TBI lost friends since the injury, partners often suffered the loss of friends that they shared with the person with TBI; in contrast, parents did not experience this as a shared loss of friends.

Wife: I would love to have a social group. They’re not there. Their answer was, he’s still sick? You know, this is not the flu. This is a brain injury. He’s always going to be sick.

Wife: I don’t fit anymore. A lot of our friends were couples. I went to some party, and they were saying, next, let’s all have a Father’s Day thing... and they just kind of looked at me, you know, because NAME doesn’t socialize with them. And they don’t want him to socialize with them, because he’s just very, very awkward.

Caregivers articulated need for help and support in a number of key areas. In regard to service providers, caregivers said they needed more information about the course of care and expected recovery for their loved one, and expressed the need for improved empathic and knowledgeable communication from rehabilitation physicians. Caregivers expressed the desire for prolonged and ongoing contact with rehabilitation professionals after their loved one was discharged. Finally, many caregivers expressed the desire for assistance with daily duties and monitoring the person with TBI so that the caregiver could run errands or take personal time. Those who did have paid assistants or family help noted the relief that even small amounts of assistance can provide a caregiver who is overwhelmed with daily responsibilities.

Caregivers did not focus solely on the negative impacts of caring for someone with a TBI. Although it constituted a relatively small amount of the focus group content, some comments reflected positive observations of growth/improvement in the person with TBI and feelings of hopefulness and determination.

Mother: When you see him fighting, it just gives you inspiration.

Other comments reflected personal resilience, positive experiences of support, efforts to cope effectively with the challenges of caregiving, and new and enlightening perspectives on life in general.

Wife: I mean, I am a fighter, and I keep going, and when one door is closed…

Husband: We’re tied into the community…Folks came together, and that was a good thing. And I think that it – I mean, it’s just I think probably good to note that when that happens, it was a big support network. Friends were taking care of the kids. Friends were taking care of the house and dog. As [wife] recovered, friends came together, and I think the social network came together again, too for her.

Mother: We, through the whole thing, have used humor to get through it, and continue to use humor. It’s just – it just makes it easier to laugh about the things that make us angry or upset, than to – it’s not that we’re dealing with it, but we try to find that humor, just to get through

Wife: I forgive myself for being human. I’ve learned to do that. Patience, I don’t know where I dig it up from sometimes when you really just want to blow your gourd [head].

Father: I guess life has changed…Now it’s like oh well, you know, nothing really matters anymore. You know like nothing is that important anymore. Before it was important to get a new car, it was important to do something else…Now it’s like, it’s important that we’re all healthy, that we’re all here.

Discussion

Previous research has established that providing care to an individual with moderate or severe TBI is related to increased psychosocial distress and poor functioning (Florian et al., 1989; Harris et al., 2001; Kolakowsky-Hayner et al., 2001; Kreutzer, Rapport, et al., 2009; Livingston et al., 1985; Marsh et al., 1998a, 1998b; McPherson et al., 2000; Perlesz et al., 2000; Ponsford et al., 2003; Ponsford & Schonberger, 2010). This study goes beyond previous examinations of caregiver burden by providing distinctive and vivid accounts of the lives of parent and partner caregivers and insight about the nuances of causes and consequences of caregiver stress, anxiety, depression, and changes in social functioning. It is crucial to develop a full understanding of the challenges and needs of caregivers to improve their well-being, which also relates to the functioning and rehabilitation outcomes for the person with TBI (Sander et al., 2002; Sander, Maestas, Sherer, Malec, & Nakase-Richardson, 2012; Smith & Schwirian, 1998; Vangel, Rapport, & Hanks, 2011).

Two meta-themes identified in the narratives capture two substantial changes that occur for the caregiver after the TBI: the adoption of new caregiver roles and responsibilities and the impact of the injury-related changes in the person who sustained the TBI. These higher-order changes are related to myriad ensuing changes represented in the subthemes of the narratives. Many of the subthemes are consistent with and augment the existing evidence. For example, findings from themes such as “No time for self-care”, “Physical toll”, “Perceived aggression”, and “New person/new relationship” are consistent with two studies that found that caregivers were most distressed about lack of personal free time, impact of caregiving on health, and the behavioral changes in the person with TBI (Marsh et al., 1998a, 1998b). However, our findings expand on the previous work to suggest antecedent processes, such as never-ending to-do-lists, being solely responsible, having no help, as well as consequences like the existential crisis of having lost one’s identity and life, anger, feeling like the bad guy, and having to “walk on eggshells.” Findings from the “Support/Helpers” theme were also consistent with previous research that suggests caregivers are discontent with instrumental and professional support (Kolakowsky-Hayner et al., 2001) and the substantial contribution of unmet needs to caregiver burden and quality of life (Ergh, Hanks, Rapport, & Coleman, 2003; Nabors, Seacat, & Rosenthal, 2002). The common theme of feeling overwhelmed by stress is consistent with a recent review that found that caregiver level of stress is substantial enough to warrant professional intervention, even long after the TBI (Verhaeghe et al., 2005).

In general, parents and partners discussed similar themes related to caregiving; however, there were some notable differences between the narratives of the parents and partners (See Supplemental Digital Content 2). For example, compared to partners, parents expressed more intense feelings of grief and sadness related to the loss of the person their child was before the TBI and the future they had envisioned for their child, and endorsed guilt and a sense of responsibility for their child’s injury, perhaps due to the protective role of parenting. Consistent with past research (Allen, Linn, Gutierrez, & Willer, 1994), parents reported more concerns for the future, e.g., worry about who will provide care when they are gone. Feeling chained or tethered to the person with TBI was also a more salient theme for parents. This may be due to the fact that partners were used to spending a great deal of time together before the injury, whereas parents had likely grown used to the independence of their adult child before they suffered the TBI. Parents talked about the caregiving role as a return to parenting a much younger (“newborn”, “adolescent”) version of their child. In contrast, partners talked about the caregiving role as a new parent/child relationship marked by loss of intimacy. Both groups described tension/resentment due to the caregiver treating the person with TBI like a child, but for partners this was a completely new dynamic, whereas for parents, it marked a return to an earlier stage of the parent/child relationship. Compared to parents, partners expressed more intense frustration and desperation about having to shoulder the caregiver burden alone and more intense stress related to feeling alone in their duties and decision making. These findings fall in line with previous research suggesting that spouses tend to experience more stress than parent caregivers (Verhaeghe et al., 2005). Partners described more negative physical and cognitive effects of caregiver stress, which is also consistent with quantitative evidence that spouses have lower perceived health status compared to parents (McPherson et al., 2000). While parent caregivers were distressed about conflict between their child with TBI and his/her siblings, partners described tremendous distress about changes in the relationships between their partner with the TBI and their children. Partners described guilt about making decisions alone, including guilt about making poor decisions and cutting their partner with the TBI out of decisions. Partners seemed to be more emotionally wounded by perceived aggression from the person with TBI compared to parents, who also suffered aggression and abuse but did not describe it in terms of a breaking down of the relationship and intimacy.

The themes identified in this study suggest areas that could be productive targets for clinical assessment and intervention and indicate that clinicians may find that parents and partner caregivers present with different clinical needs. In order to address caregiver emotional distress, clinicians may provide grief counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, and stress management training (including mindfulness-based strategies) to help caregivers to work through grief, guilt, and stress related the injury of their loved one. Preliminary studies investigating targeted interventions for caregivers have yielded promising results for interventions that include education, stress management, cognitive-behavioral techniques (e.g., cognitive reframing), and an emphasis on self-care (Kreutzer, Kolakowsky-Hayner, Demm, & Meade, 2002; Kreutzer, Stejskal, et al., 2009; Sander, 2005). The accounts of many caregivers suggest the need for ongoing help specifically with problem solving; this need might be particularly common in partner caregivers who are more likely to be making decisions alone. Indeed, there is evidence that training in problem-solving contributes to decreased depressive symptoms, improved perceived health, and less dysfunctional problems solving style for caregivers (Rivera, Elliott, Berry, & Grant, 2008). Caregivers in the current study also demonstrated a need for instrumental support, which may be met through established community, government, or hospital-based programs.

Strengths & Limitations

We completed a number of steps to ensure that our research process and findings are reliable, valid, and “trustworthy.” To ensure credibility (similar to internal validity) we attempted to recruit a diverse sample of caregivers to represent a wide range of experiences. Further, members of the study team are experienced in TBI research and clinical care and have regular contact with caregivers of individuals with TBI (Catanzaro, 1988; Chwalisz, Shah, & Hand, 2008; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Miles et al., 2014). Credibility is supported if the accounts are logical, convincing, and “ring true.” Transferability (similar to external validity) was supported by the fact that the findings are consistent with prior findings and current concepts. To optimize dependability (analogous to reliability) our data analysis included stepwise replication involving multiple researchers who deal with the data separately, and researcher triangulation, where multiple researchers analyze the data (Catanzaro, 1988; Chwalisz et al., 2008; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Miles et al., 2014). By attempting to explain the study procedures in clear detail and by using an audit we established confirmability (analogous to external reliability).

The fact that we used focus groups consisting of men and women representing a variety of types of relationships with the care recipient may impact the generalizability of our findings. All participants were caring for individuals who were at least one year out from injury, therefore findings may not be generalizable to caregivers who are in the transition period shortly after injury. Because there were few male participants and mixed-gender groups were conducted, we may not have obtained sufficient male perspective, especially from husbands who may not have felt comfortable discussing topics such as intimacy in mixed company. Also, because there were few men, we were not able to examine differences between wives/husbands, mothers/fathers and findings may be more generalizable to women caregivers, in general. Most of the comments made by caregivers reflected the challenges and negative impact of caregiving on their quality of life; the focus group methodology and process may not have encouraged participants to contemplate or disclose the positive aspects of being a caregiver. Furthermore, the recruitment strategy (e.g. convenience sampling) may have resulted in a sample of caregivers who are facing more challenges than is typical across all caregivers of individuals with TBI. The sample also had few people who were caring for someone who was recently injured and future studies may examine how caregiver needs change over time, from the acute phase to long-term care. An additional limitation of the study is that it was not designed to explore differences between parents and partners. However, the fact that these group differences emerged without probing and were even noticed and commented on by focus group participants suggests that the challenges for parent versus partner caregivers are significant and blatant.

Conclusions

Caring for an individual with TBI is marked by a multitude of changes in roles and responsibilities for the caregiver, and changes to the relationship between the caregiver and care-recipient. These changes have a variety of negative impacts on caregiver health and functioning. While parents and partners both face similar changes, the qualitative experience of the caregiving role has unique challenges for each. Interventions for caregivers are warranted, with attention to the unique experiences of parents and partner caregivers. Although there is a growing body of literature related to family interventions after brain injury, the research lacks consistent/convincing findings and methodological rigor(For review see Boschen, Gargaro, Gan, Gerber, & Brandys, 2007) indicating the need for the development of theoretical models to guide intervention development (Boschen, Gargaro, Gan, Gerber, & Brandys, 2007). Differences in the quality of the caregiving experience for parent versus spouse caregivers should be incorporated into these theoretical models in order to guide more individualized treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research under grant #1R01-NR013658-01. The authors thank research staff, Amy Austin, B.S., Curtisa Light, MLA, Dennis Tirri, B.S., for their assistance. During manuscript development, Dr. Kratz was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases under grant # 1K01AR064275. The authors give special thanks Colette Duggan, PhD for her helpful guidance regarding data analysis. We are tremendously grateful to the caregivers of loved ones with TBI, who openly shared their experiences with us. For some authors (RTL and TAB), the views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official Department of Defense position, policy or decision unless so designated by other official documentation.

Contributor Information

Angelle M. Sander, Baylor College of Medicine & Harris Health System, TIRR Memorial Hermann’s Brain Injury Research Center, Houston, TX, USA, Angelle.Sander@memorialhermann.org..

Tracey A. Brickell, Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA, tracey.a.brickell@us.army.mil..

Rael T. Lange, Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA, Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, rael.t.lange@us.army.mil..

Noelle E. Carlozzi, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. Phone: +1 (734) 763-8917, Carlozzi@med.umich.edu..

References

- Allen K, Linn RT, Gutierrez H, Willer BS. Family Burden Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1994;39(1):29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855–866. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschen K, Gargaro J, Gan C, Gerber G, Brandys C. Family interventions after acquired brain injury and other chronic conditions: a critical appraisal of the quality of the evidence. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22(1):19–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualtiative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Kratz AL, Sander AM, Chiaravalloti ND, Brickell TA, Lange RT, Tulsky DS. Health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: development of a conceptual model. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson P. Investing in the comeback: parent’s experience following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Nurs. 1993;25(3):165–173. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro M. Using Qualitative Analytical Techniques. In: Wood NF, Catanzaro M, editors. Nursing Research: Theory and Practice. The C.V. Mosby Company; St. Louis, MO: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chwalisz K, Shah SR, Hand KM. Facilitating rigorous qualitative research in rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53(3):387–399. [Google Scholar]

- Chwalisz K, Stark-Wroblewski K. The subjective experiences of spouse caregivers of persons with brain injuries: a qualitative analysis. Appl Neuropsychol. 1996;3(1):28–40. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an0301_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Strategies of qualitative inquiry. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ergh TC, Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, Coleman RD. Social support moderates caregiver life satisfaction following traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25(8):1090–1101. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.8.1090.16735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian V, Katz S, Lahav V. Impact of traumatic brain damage on family dynamics and functioning: a review. Brain Injury. 1989;3(3):219–233. doi: 10.3109/02699058909029637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill CJ, Sander AM, Robins N, Mazzei DK, Struchen MA. Exploring Experiences of Intimacy From the Viewpoint of Individuals With Traumatic Brain Injury and Their Partners. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2011;26(1):56–68. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182048ee9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing Company; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin E, Chappell B, Kreutzer J. Relationships after TBI: A grounded research study. Brain Injury. 2014;28(4):398–413. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.880514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond FM, Davis CS, Whiteside OY, Philbrick P, Hirsch MA. Marital adjustment and stability following traumatic brain injury: a pilot qualitative analysis of spouse perspectives. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26(1):69–78. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318205174d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JK, Godfrey HP, Partridge FM, Knight RG. Caregiver depression following traumatic brain injury (TBI): a consequence of adverse effects on family members? Brain Inj. 2001;15(3):223–238. doi: 10.1080/02699050010004040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BP. One family’s experience with head injury: a phenomenological study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1995;27(2):113–118. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199504000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Miner KD, Kreutzer JS. Long-term life quality and family needs after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2001;16(4):374–385. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer JS, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Demm SR, Meade MA. A structured approach to family intervention after brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2002;17(4):349–367. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer JS, Rapport LJ, Marwitz JH, Harrison-Felix C, Hart T, Glenn M, Hammond F. Caregivers’ well-being after traumatic brain injury: a multicenter prospective investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(6):939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer JS, Stejskal TM, Ketchum JM, Marwitz JH, Taylor LA, Menzel JC. A preliminary investigation of the brain injury family intervention: impact on family members. Brain Inj. 2009;23(6):535–547. doi: 10.1080/02699050902926291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre H, Cloutier G, Josee Levert M. Perspectives of survivors of traumatic brain injury and their caregivers on long-term social integration. Brain Inj. 2008;22(7-8):535–543. doi: 10.1080/02699050802158243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston MG, Brooks DN, Bond MR. Three months after severe head injury: psychiatric and social impact on relatives. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1985;48(9):870–875. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.48.9.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JH, Sleigh JW. Caregiver burden at 1 year following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 1998a;12(12):1045–1059. doi: 10.1080/026990598121954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JH, Sleigh JW. Caregiver burden at 6 months following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 1998b;12(3):225–238. doi: 10.1080/026990598122700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson KM, Pentland B, McNaughton HK. Brain injury - the perceived health of carers. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22(15):683–689. doi: 10.1080/096382800445489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nabors N, Seacat J, Rosenthal M. Predictors of caregiver burden following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2002;16(12):1039–1050. doi: 10.1080/02699050210155285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlesz A, Kinsella G, Crowe S. Psychological distress and family satisfaction following traumatic brain injury: injured individuals and their primary, secondary, and tertiary carers. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2000;15(3):909–929. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsford J, Olver J, Ponsford M, Nelms R. Long-term adjustment of families following traumatic brain injury where comprehensive rehabilitation has been provided. Brain Injury. 2003;17(6):453–468. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000070143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsford J, Schonberger M. Family functioning and emotional state two and five years after traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(2):306–317. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709991342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version Version 10) 2012.

- Rivera PA, Elliott TR, Berry JW, Grant JS. Problem-solving training for family caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(5):931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Balzer K, Harris J, Moldovan R. A qualitative needs assessment of persons who have experienced traumatic brain injury and their primary family caregivers. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(1):14–25. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander AM. A cognitive-behavioral intervention for family members with TBI. In: Zasler N, Zafonte RD, Katz D, editors. Brain Injury Medicine. Demos Publishing; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 1117–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Sander AM, Caroselli JS, High WM, Becker C, Neese L, Scheibel R. Relationship of family functioning to progress in a post-acute rehabilitation programme following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2002;16(8):649–657. doi: 10.1080/02699050210128889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander AM, Maestas KL, Sherer M, Malec JF, Nakase-Richardson R. Relationship of caregiver and family functioning to participation outcomes after postacute rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: a multicenter investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(5):842–848. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AM, Schwirian PM. The relationship between caregiver burden and TBI survivors’ cognition and functional ability after discharge. Rehabil Nurs. 1998;23(5):252–257. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1998.tb01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson HJ. A critical analysis of measures of caregiver and family functioning following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Nurs. 2009;41(3):148–158. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181a23eda. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Data Center Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Data Base Inclusion Criteria. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.tbindsc.org/Documents/2010%20TBIMS%20Slide%20Presentation.pdf.

- Vangel SJ, Jr., Rapport LJ, Hanks RA. Effects of family and caregiver psychosocial functioning on outcomes in persons with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26(1):20–29. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318204a70d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe S, Defloor T, Grypdonck M. Stress and coping among families of patients with traumatic brain injury: a review of the literature. Journal of clinical nursing. 2005;14(8):1004–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.