Review on the interplay between stress and cytokine dysregulation in inflammation, in both healthy individuals and CAPS patients.

Keywords: interleukin-1 family, ATP secretion, TLR agonist, NLRP3 inflammasome

Abstract

The cell stress and redox responses are increasingly acknowledged as factors contributing to the generation and development of the inflammatory response. Several inflammation-inducing stressors have been identified, inside and outside of the cell. Furthermore, many hereditary diseases associate with inflammation and oxidative stress, suggesting a role for mutated proteins as stressors. The nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat-containing family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is an important node at the crossroad between redox response and inflammation. Remarkably, monocytes from patients with mutations in the NLRP3 gene undergo oxidative stress after stimulation with minute amounts of TLR agonists, resulting in unbalanced production of IL-1β and regulatory cytokines. Similar alterations in cytokine production are found in healthy monocytes upon TLR overstimulation. This mini-review summarizes recent progress in this field, discusses the molecular mechanisms underlying the loss of control of the cytokine network following oxidative stress, and proposes new therapeutic opportunities.

Introduction

Inflammation is classically defined as a defense response of cells to harmful stimuli, induced by pathogen components (PAMPs) that mediate infectious inflammation or by substances released by injured tissues (DAMPs) responsible for sterile inflammation through activation of TLRs and NLRs [1, 2]. However, recent studies suggest that a strong role in inflammation, even in the absence of PAMPs or DAMPs, is played by stress [3]. Living cells are equipped with devices that physiologically allow them to respond and adapt rapidly to stress [4]. Among them, the UPR has been traditionally viewed as an adaptive response to the stress triggered by accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER and aimed at restoring ER function. At present, defects in protein folding, either induced environmentally or caused by genetic mutations in components of the UPR, are recognized as able to trigger by themselves an inflammatory phenotype [5], as described in inflammatory bowel disease [6], metabolic disease [7], and lung respiratory disease [8]. The UPR intersects at various levels with inflammatory pathways, such as the production of ROS and the activation of NF-κB, JNK, and IFN-regulatory factor 3, resulting in induction and amplification of the cytokine response. Furthermore, activation of TLRs by PAMPs or DAMPs may activate UPR signaling cascades, indicating that different inducers of inflammation are connected and may synergize [9–11].

It is noteworthy that many hereditary diseases, including cystic fibrosis [12] and Duchenne muscular dystrophy [13], are associated with inflammation and oxidative stress. Conceivably, the presence of a mutated protein disrupts the cell proteostasis, causing stress—including ER stress and redox stress—UPR, and inflammation. We reasoned that the presence of a stress-inducing mutated protein in professional inflammatory cells, where all of the circuits dedicated to the induction of inflammation are prone to activation, would have a stronger impact on the development and outcome of the inflammatory response. In agreement with this hypothesis, monocytes from patients affected by CAPS, an AID where mutations in the inflammasome component NLRP3 cause severe inflammatory manifestations, display a state of cell stress at baseline [14]. It is noteworthy that monocytes from healthy subjects, when overstimulated by different TLR agonists, also become stressed and behave similarly to CAPS monocytes [15]. Here, we discuss the role of stress responses in the production of proinflammatory and regulatory cytokines by inflammatory cells and compare monocytes from CAPS patients with overstimulated, healthy monocytes.

CAPS

AIDs, also called periodic fever syndromes, are a family of rare hereditary disorders, characterized by unexplained episodes of fever and systemic and organ-specific inflammation in the absence of high titers of autoantibodies or antigen-specific T or B cells [16–18]. In many AIDs, the responsible gene is related to the innate immunity [19]. CAPS is linked to mutations in the NLRP3 gene [20, 21], a major component of the inflammasome, responsible for processing and secretion of IL-1β and other cytokines [22]. CAPS includes 3 different clinical forms: familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, and chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, and arthritis syndrome, which differ in the organs involved and in the severity of the disease [19]. The missense mutations in the highly conserved NACHT domain of NLRP3 cause inflammasome hyperactivity and dysregulated production of IL-1β that is responsible for the severe inflammatory manifestations [22, 23]. The key role of IL-1β has been confirmed by the rapid and sustained resolution of symptoms observed by blocking IL-1R with anakinra, the recombinant form of the endogenous IL-1Ra, or neutralizing IL-1β with anti-IL-1β (canakinumab) [24–26].

IL-1β AND IL-1Ra

IL-1β is a master mediator of inflammation, produced by inflammatory cells following TLR activation, which directly or through induction of other cytokines is able to trigger inflammatory responses in virtually all tissues of our body [27]. As a result of the high bioactivity and the pleiotropic functions of the cytokine, dysregulated secretion of IL-1β is highly dangerous, as demonstrated by its involvement in the pathogenesis of several inflammatory disorders, including type 1 diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, inflammatory bowel disease, and rheumatoid arthritis [28].

In healthy individuals, the acute inflammatory response is generally self-limiting, as a result of the presence of several down-modulating circuits. IL-1Ra, a member of the IL-1 family, is the most important physiologic inhibitor of IL-1. It binds to IL-1R with the same affinity as IL-1 but does not signal, thus inhibiting binding and activity of IL-1. IL-1Ra is induced by IL-1 itself, both in peripheral target tissues and in an autocrine/paracrine manner, on the same monocytes that produce IL-1. Thus, after a phase of autoinduction [27, 29], IL-1 starts a negative feedback loop, with induction of IL-1Ra, which, in turn, competes with IL-1 at the IL-1R level, thus dampening inflammation (Fig. 1). The balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra is not only essential for controlling the outcome of inflammation, but it also plays a role in preventing its onset and maintaining the homeostasis, as evidenced in patients affected by genetic deficiency of IL-1Ra [30]. These babies already exhibit at birth devastating inflammatory lesions without evidence of a triggering stimulus, which frequently led them to death in a few years. If the syndrome is recognized early, treatment with anakinra can prevent death from multiorgan failure and dramatically ameliorates the inflammatory manifestations with rapid resolution of the symptoms and signs [30].

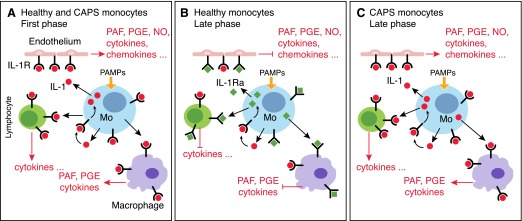

Figure 1. IL-1Ra in healthy and CAPS monocytes.

(A) PAMP-activated monocytes secrete IL-1β that binds IL-1Rs on different target cells, including endothelium, lymphocytes, and macrophages. The activation of IL-1R triggers the production of secondary mediators that amplify the inflammatory response. In a first phase from PAMP stimulation, IL-1β induces itself on monocytes, thus generating an amplifying loop. (B) In a later phase (3–6 h from PAMP stimulation), healthy monocytes start producing IL-1Ra, which binds IL-1R but does not signal, thus limiting the activities of IL-1 and dampening inflammation. (C) In CAPS monocytes, oxidative stress inhibits IL-1Ra production. The deficiency of IL-1Ra increases the IL-1-mediated effects and contributes to generation of severe inflammatory manifestations in CAPS patients. PAF, platelet-activating factor; Mo, monocyte.

NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME

Unlike most cytokines, IL-1β is a leaderless protein and is secreted by monocytic cells through a nonclassic pathway [31]. Moreover, IL-1β is synthesized as an inactive precursor (pro-IL-1β) and processed in the biologically active form by caspase-1, activated upon the assembly of the cytosolic multiprotein complex called inflammasome [32].

Secretion of IL-1β requires 2 signals [33–35]. Microbial products, such as PAMPs, induce expression and intracellular accumulation of pro-IL-1β; then, inflammasome activators trigger the assembly of the inflammasome, leading to pro-IL-1β processing and secretion of IL-1β [36, 37].

Different inflammasomes exist, composed by different members of the NLR family. In this review, we will focus on the NLRP3 inflammasome that is responsible for IL-1β activation during sterile inflammation and that is mutated in CAPS. The NLRP3 inflammasome is composed by NLRP3, the adaptor protein ASC, and procaspase-1 [34]. ASC mediates the recruitment to NLRP3 of procaspase-1, inducing its autoprocessing, with generation of active caspase-1 able to cleave pro-IL-1β and to convert it to the mature IL-1β [38]. NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated by a range of microbial and nonmicrobial stimuli. Nonmicrobial stimuli, involved in sterile inflammation, include substances that through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, lead to the development of specific diseases. This is the case of uric acid crystals that cause the acute inflammation in gout [39]; asbestos and silica fibers, responsible for the inflammation leading to pulmonary fibrosis (asbestosis, silicosis) [40]; and β-amyloid fibers and cholesterol crystals implicated in Alzheimer’s disease [41] and atherosclerosis [42], respectively.

Other nonmicrobial activators of NLRP3 inflammasome are unlinked to specific diseases and activate the inflammasome in many different inflammatory contexts. Among these, the most common is extracellular ATP.

EXOGENOUS ATP AS THE MOST COMMON NLRP3 ACTIVATOR

ATP is a well-known energy-bearing molecule, present in living cells, that provides the energy required by key cell processes, such as metabolism, biosynthesis, and intracellular signaling. Yet, this versatile molecule is also present extracellularly, where it plays important functions in cell–cell communication and regulates many physiologic or pathologic processes in different organs and tissues. In inflammation, extracellular ATP acts as a DAMP [43]. In fact, being present at high concentration inside of cells, ATP is released extracellularly in large amounts upon cell injury. ATP can also be actively secreted by activated living cells, such as platelets and leukocytes [43], through mechanisms only partially understood [44, 45]. Either passively released or actively secreted, extracellular ATP induces inflammation by binding P2X7R on inflammatory cells and triggering a series of intracellular processes that leads to inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion [43, 46]. Exogenous ATP is necessary in macrophages, but it is dispensable in human monocytes [47–49], as TLR stimulation activates secretion of endogenous ATP that in an autocrine manner, stimulates P2X7R and triggers inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 2) [49]. The extracellular ATP concentrations are controlled by a family of ectoenzymes that continuously remove ATP, thus dampening inflammation. In particular, activated monocytes express the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 that mediate the hydrolysis of ATP, thereby reducing the production of IL-1β [50, 51].

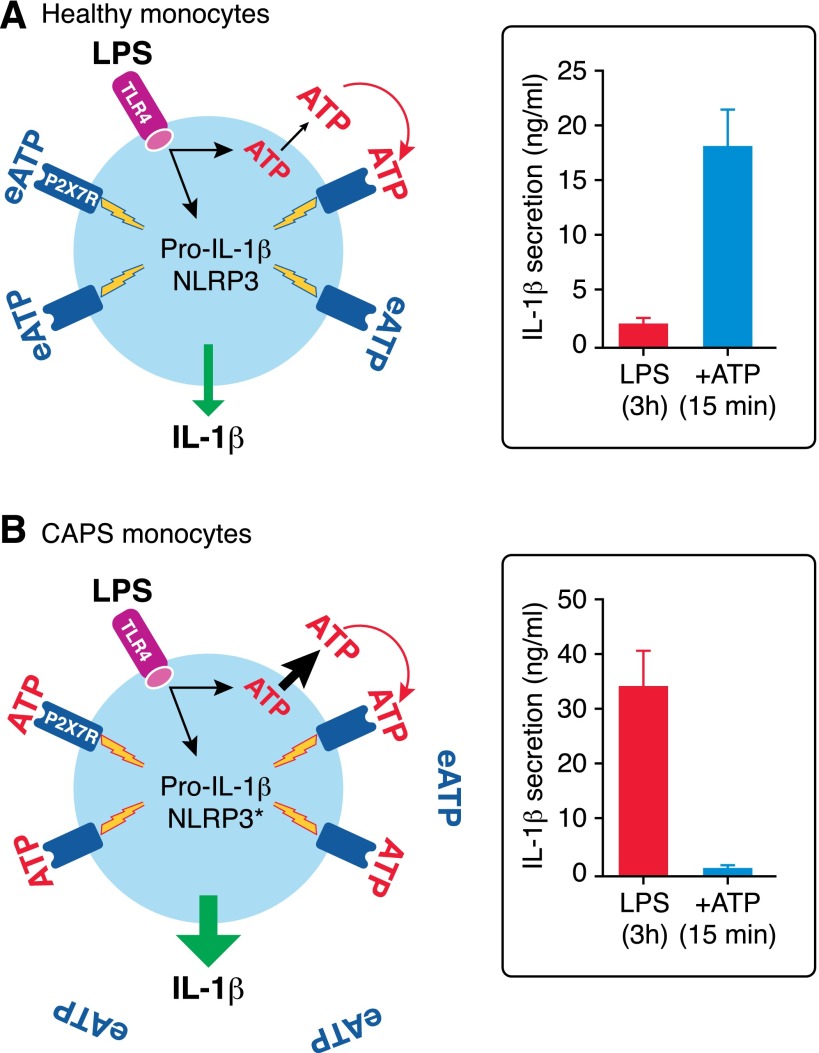

Figure 2. Stress-dependent ATP release prevents exogenous ATP-induced IL-1β secretion in CAPS monocytes.

(A) In healthy monocytes, LPS stimulation induces synthesis and intracellular accumulation of pro-IL-1β, release of endogenous ATP (ATP, red), which in an autocrine manner, stimulates P2X7R, leading to inflammasome activation. The amount of released ATP is small, resulting in processing and secretion of little amounts of IL-1β. Exposure to exogenous ATP (eATP, blue) after 3 h from LPS stimulation dramatically induces IL-1β processing and secretion. (B) In CAPS monocytes, LPS stimulation triggers the release of high amounts of ATP that are sufficient to drive processing and secretion of the maximal levels of IL-1β by autocrine stimulation of P2X7R. Therefore, exogenous ATP is not effective. NLRP3*, mutated NLRP3.

DYSREGULATED CYTOKINE PRODUCTION IN CAPS

As introduced above, CAPS is characterized by dysregulated production of IL-1β that is linked to NLRP3 gain-of-function mutations and that represents the hallmark of CAPS. Following stimulation with TLR agonists, IL-1β secretion is not only increased, but also accelerated [14, 51], whereas IL-1β secretion by monocytes from healthy donors is still increasing after 18 h from the exposure to PAMPs, in monocytes from CAPS patients, the plateau is reached after 3 to 6 h. Of course, the release of all of the secretable IL-1β altogether after a single stimulus justifies the strong inflammatory symptoms, even in the absence of a high increase of secretion.

In addition to IL-1β, other cytokines are dysregulated in CAPS, possibly contributing to the pathophysiology of the disease. In a recent study [52], we observed that IL-18 and IL-1α secretion is also increased in LPS-stimulated monocytes from CAPS patients. IL-18, like IL-1β, is processed by inflammasome-activated caspase-1; thus, its increase is expected. In contrast, IL-1α is not; rather, IL-1α is bioactive as a nonprocessed precursor [53] and is able to exert its proinflammatory activity when released by dying cells, thus behaving as a DAMP [54]. However, IL-1α can also be actively secreted in response to cell stress [55]. Furthermore, the inflammasome has been found to mediate IL-1α secretion, in spite of the cytokine lacking a site of cleavage for caspase-1 [56, 57]. In CAPS, the increased secretion of IL-1α implies its possible involvement in the promotion and progression of inflammatory episodes and must be kept in account when anti-IL-1β therapies are considered.

Unexpectedly, furthermore, the production of cytokines downstream of IL-1β is dysregulated in CAPS, with dramatic impairment of IL-1Ra and IL-6 secretion [51]. This impairment is likely to have a strong impact on the disease, as the deficiency of IL-1Ra allows the amplification of IL-1-mediated effects. Thus, the low availability of IL-1Ra explains the severe inflammatory manifestations in CAPS patients, as well as with those cases where the increase in IL-1β secretion is moderate (Fig. 1). Less clear is whether the low secretion of IL-6 by CAPS monocytes has a role in the disease. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine and can exert pro- and anti-inflammatory properties, possibly depending on signaling through membrane-bound or soluble IL-6Rs [58]. Moreover, the IL-6 in CAPS serum, even if lower than in other autoinflammatory or autoimmune diseases [24, 59], is, in any case, above the normal range, most likely as a result of the fact that IL-6 is produced not only by monocytes but also by several cell types following IL-1β stimulation. The different rate of IL-6 production may explain why agents targeting IL-6 are highly beneficial in autoimmune diseases [60] but have no sustained effects in CAPS that conversely, are highly responsive to IL-1 blockade [26].

WHY ARE CYTOKINES DYSREGULATED IN CAPS? THE ROLE OF CELL STRESS

CAPS monocytes are under redox distress

In normal cells, when ROS production occurs, as a result of physiologic or pathologic triggers, an adaptive response with induction of some of the several antioxidant systems present in cells is rapidly activated, aimed at restoring the redox balance. Once the homeostasis is restored, antioxidant systems return to baseline. Thus, unstimulated monocytes from healthy subjects exhibit a condition of redox equilibrium with low amounts of ROS and of antioxidants. In contrast, monocytes from CAPS patients are under redox stress. Freshly drawn from peripheral blood, in the absence of any stimulation, CAPS monocytes display elevated levels of both ROS and antioxidants. A redox equilibrium is still present but precarious, as it is maintained by a strong and continuous overexpression of antioxidant systems that try to compensate the high levels of ROS. Accordingly, signs of stress, such as the presence of damaged mitochondria, are detected in circulating CAPS monocytes [51]. This state of stress is likely linked to the presence of the mutated NLRP3 protein, as also suggested by the observation that lymphocytes from CAPS patients, which different from monocytes, do not express NLRP3, have normal mitochondria [51].

Cell stress increases the production of IL-1β by inducing ATP secretion

Stress at baseline results in an altered response of CAPS monocytes to TLR stimulation. Triggering of TLRs induces a stronger generation of ROS, which in turn, causes an increased secretion of ATP (up to 10 times that induced in healthy monocytes; Fig. 2) [52]. The key role of ROS in inducing ATP secretion was confirmed by the observation that the inhibition of ROS production by the flavoprotein inhibitor, diphenyleneiodonium, strongly hinders the secretion of ATP. The P2X7R blocker, oxidized ATP, dramatically prevents IL-1β secretion, further demonstrating the direct involvement of externalized ATP in inflammasome activation through engagement of P2X7R [52]. How ROS induce ATP secretion is still unclear. A recent study on keratinocytes suggests that ROS production leads to ATP release through opening of pannexin hemichannels [61, 62], which also can be implicated in monocytes, as they are ubiquitously expressed [63], and they mediate ATP release [64] and IL-1β secretion [65] also in these cells. In any case, the loop involving ROS production, ATP release, P2X7R triggering, and inflammasome activation, implicated in TLR-mediated IL-1β secretion in normal monocytes [15, 49], is also present in CAPS monocytes, where it is strongly amplified, suggesting a correlation between redox distress and ATP secretion [52].

Following TLR stimulation and the consequent strong generation of ROS, CAPS monocytes release ATP levels higher than those necessary to trigger the maximal IL-1β secretion [52]. These data provide a mechanistic explanation to the findings that the addition of exogenous ATP does not stimulate IL-1β secretion by LPS-primed CAPS monocytes [25]. As a result of the high levels of ROS-induced, secreted ATP and the consequent high levels of secreted IL-1β, additional extracellular ATP is unable to increase the release of the cytokine further.

Stress lowers the threshold of inflammasome activation

An additional consequence of the state of stress present at baseline in CAPS monocytes is the lower threshold of PAMP-mediated inflammasome activation. Minute amounts of LPS, unable to induce inflammasome activation in healthy monocytes, trigger high levels of IL-1β secretion by CAPS monocytes [52]. This feature may explain the recurrent episodes of systemic inflammation in the absence of evident clinical cause. Slight stimuli, such as very mild trauma or upper-respiratory viral infections, inconsequential in healthy subjects, may induce IL-1β secretion and dramatic inflammatory manifestations in CAPS patients.

Remarkably, the presence of stress also is a feature of monocytes from the TNFR associated periodic syndrome [66], the FMF [67], and the NLRP12 associated periodic syndrome [68]. These observations strongly support the hypothesis that stress is a hallmark of monocytes from autoinflammatory syndromes, linked to the expression of a mutated protein in inflammatory cells [69], and that it participates in the pathophysiology of the disease at different extents, depending on the severity of the stress state.

Stress impairs the production of IL-1Ra

In this regard, whereas the mild stress state in certain AIDs, such as FMF only causes an increased IL-1β secretion, the stronger stress present in CAPS monocytes also leads to impaired production of regulatory cytokines, such as IL-1Ra. In fact, the antioxidant response, activated in PAMP-stimulated CAPS monocytes to detoxify the increased ROS production, is effective for only a few hours but then collapses, resulting in oxidative stress [14, 51]. Stressed cells down-modulate the global translation [70, 71] so that the production of second-wave cytokines, such as IL-1Ra, normally expressed at 3–6 h from TLR triggering, also is reduced dramatically. The inhibition of protein synthesis may also explain why IL-1β secretion by LPS-stimulated CAPS monocytes peaks between 3 and 6 h and then stops, whereas in normal monocytes, IL-1β secretion, although much lower, is sustained in time.

Previous observations, reporting that the levels of serum IL-1Ra are higher in CAPS than in healthy subjects [23], are only apparently in disagreement. In fact, serum IL-1Ra derives from many cell sources, as many cell types produce this cytokine. As discussed above, cell stress in CAPS is a result of the expression of the mutated NLRP3. Thus, inhibition of protein translation, with decreased synthesis of IL-1Ra, would occur only in inflammatory cells. The impaired production of IL-1Ra, coupled to increased secretion of IL-1β, therefore, would be relevant in the inflammatory microenvironment, where monocytes/macrophages are recruited, such as joints, where the strong IL-1/IL-1Ra unbalance would intensify the inflammation [30, 72]. The critical role of oxidative stress [51] was supported by the observation that antioxidants are able to restore the production of IL-1Ra by CAPS monocytes in vitro [52]. This finding confirms that restoring redox homeostasis could rescue the production of regulatory cytokines, helping to control inflammation [73].

DOES STRESS ALSO AFFECT THE INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE IN MONOCYTES FROM HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS?

The cross-talk between stress and loss of control of the inflammatory cytokine network is increasingly acknowledged as a pathogenetic factor in many chronic syndromes [74]. Among other examples, the presence of redox distress in monocytes upon LPS stimulation could explain the increased IL-1β and decreased IL-6 production reported in subjects at risk for diabetes development [75].

It is noteworthy that also in severe acute inflammatory reactions, such as sepsis, an imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production may play an important role in pathogenesis [76]. Remarkably, signs of oxidative stress, such as NO overproduction, antioxidant depletion, and mitochondrial dysfunction, occur and correlate with the severity of sepsis [77, 78].

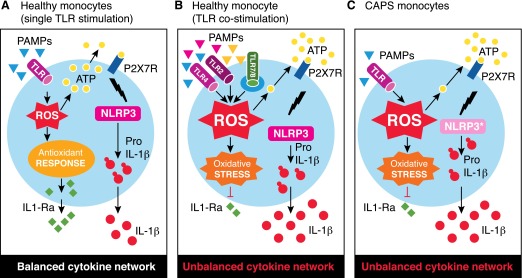

In spite of these observations, why the balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines is lost in various inflammatory conditions is incompletely understood. Recently, we showed [15] that the agonists of TLR4, -2, and -7/8, administrated singularly, trigger the proper secretion of IL-1β and IL-1Ra by normal monocytes. When provided simultaneously, however, they strongly increase the secretion of IL-1β but antagonize that of IL-1Ra. Costimulation-induced synergy and antagonism are not restricted to the IL-1β/IL-1Ra couple but affect the production of other mediators of inflammation, such as TNF-α, which is enhanced, and IL-6, which is inhibited [15]. All of these effects are mediated by redox responses. Whereas TNF-α and IL-1β are induced by the increased ROS (and the consequent increased release of ATP), the impaired IL-1Ra and IL-6 production depends on the oxidative stress that occurs in a later phase after TLR costimulation. The key role of oxidative stress in the inhibition of cytokines production, also in overstimulated, healthy monocytes, is supported by the occurrence of a block of protein synthesis that is likely responsible for the impaired production of IL-1Ra and IL-6 and by the rescue of the production of the 2 cytokines by exogenous antioxidants [15]. Thus, the mechanism of stress-induced dysregulation of cytokine production operating in normal monocytes is similar to that described for CAPS monocytes (Fig. 3). The difference is that CAPS monocytes are under stress at baseline and therefore, require a slight stimulation to increase the state of stress and eventually undergo oxidative stress, whereas normal monocytes are in a condition of redox homeostasis that ensures them a correct response unless an overstimulation of TLR arises [15].

Figure 3. A model for stress-mediated dysregulation of cytokine secretion in overstimulated, normal monocytes and CAPS monocytes.

(A) In healthy monocytes, stimulation of a single TLR induces the production of low amounts of ROS, rapidly neutralized by the antioxidant response. The ROS-induced ATP release is small, resulting in processing and secretion of little amounts of IL-1β. Later, anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1Ra, are produced, contributing to switch off the inflammatory response. (B and C) In healthy monocytes costimulated with different TLR agonists (B) and CAPS monocytes stimulated with minute amounts of a single TLR agonist (C), a massive production of ROS occurs, resulting in release of large amounts of endogenous ATP and processing and secretion of high levels of IL-1β. In both B and C, the antioxidant response to increased ROS production fails, resulting in oxidative stress responsible for the impaired production of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this review, we pointed out that similar mechanisms contribute to the loss of control of cytokine production in many different diseases, both inherited, such as AIDs, or acquired, chronic (e.g., diabetes), or acute (e.g., sepsis). In all case, stress plays a pivotal role. The pharmacological control of the clinical manifestations in stress-mediated inflammatory diseases is difficult. In many AIDs, IL-1 blocking is extremely efficient, but anti-IL-1 biologics are expensive and not available in all countries; in the case of diabetes, the sharp increase of its incidence in Western and developing countries is becoming one of the major world health emergencies. As for sepsis, no effective treatments are actually available. For these reasons, there is a strong need for new drugs—efficacious, sustainable, and widely accessible. We propose that novel therapeutic approaches, based on a combination of redox modulators and TLR [79] or P2X7R inhibitors [80], may be successful, both in acute inflammatory diseases, such as sepsis, and in chronic, pathologic conditions, including autoimmune diseases, diabetes, chronic heart failure, and cancer.

AUTHORSHIP

S.C., R.L., and A.R. designed and wrote the review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by the Italian Ministry of Health [“Young Investigators” Grant GR-2010-2309622 (to S.C.) and Ricerca Corrente (to A.R.)]; by Grant No. GGP14144 from Telethon, Rome, Italy (to A.R.); and by Grant IG 2014, Id. 15434, from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC; to A.R.). The authors thank Dr. Marco Gattorno and the members of the authors' lab for thorough and fruitful discussions.

Glossary

- AID

autoinflammatory disease

- ASC

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain

- CAPS

cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FMF

familial Mediterranean fever syndrome

- IL-1Ra

IL-1R antagonist

- NACHT

NAIP (neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein), CIITA (MHC class II transcription activator), HET-E (incompatibility locus protein from Podospora anserina), TP1 (telomerase-associated protein)

- NLR

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor

- NLRP3

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat-containing family, pyrin domain-containing 3

- P2X7R

P2X purinoceptor 7

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- UPR

unfolded protein response

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takeuchi O., Akira S. (2010) Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140, 805–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen G. Y., Nuñez G. (2010) Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 826–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chovatiya R., Medzhitov R. (2014) Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Mol. Cell 54, 281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubartelli A., Sitia R. (2009) Stress as an intercellular signal: the emergence of stress-associated molecular patterns (SAMP). Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2621–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssens S., Pulendran B., Lambrecht B. N. (2014) Emerging functions of the unfolded protein response in immunity. Nat. Immunol. 15, 910–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adolph T. E., Tomczak M. F., Niederreiter L., Ko H. J., Böck J., Martinez-Naves E., Glickman J. N., Tschurtschenthaler M., Hartwig J., Hosomi S., Flak M. B., Cusick J. L., Kohno K., Iwawaki T., Billmann-Born S., Raine T., Bharti R., Lucius R., Kweon M. N., Marciniak S. J., Choi A., Hagen S. J., Schreiber S., Rosenstiel P., Kaser A., Blumberg R. S. (2013) Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature 503, 272–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotamisligil G. S. (2010) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 140, 900–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osorio F., Lambrecht B., Janssens S. (2013) The UPR and lung disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 35, 293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinon F., Chen X., Lee A. H., Glimcher L. H. (2010) TLR activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 11, 411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savic S., Ouboussad L., Dickie L. J., Geiler J., Wong C., Doody G. M., Churchman S. M., Ponchel F., Emery P., Cook G. P., Buch M. H., Tooze R. M., McDermott M. F. (2014) TLR dependent XBP-1 activation induces an autocrine loop in rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. J. Autoimmun. 50, 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu Q., Zheng Z., Chang L., Zhao Y. S., Tan C., Dandekar A., Zhang Z., Lin Z., Gui M., Li X., Zhang T., Kong Q., Li H., Chen S., Chen A., Kaufman R. J., Yang W. L., Lin H. K., Zhang D., Perlman H., Thorp E., Zhang K., Fang D. (2013) Toll-like receptor-mediated IRE1α activation as a therapeutic target for inflammatory arthritis. EMBO J. 32, 2477–2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziady A. G., Hansen J. (2014) Redox balance in cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 52, 113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terrill J. R., Radley-Crabb H. G., Iwasaki T., Lemckert F. A., Arthur P. G., Grounds M. D. (2013) Oxidative stress and pathology in muscular dystrophies: focus on protein thiol oxidation and dysferlinopathies. FEBS J. 280, 4149–4164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tassi S., Carta S., Delfino L., Caorsi R., Martini A., Gattorno M., Rubartelli A. (2010) Altered redox state of monocytes from cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes causes accelerated IL-1β secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9789–9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavieri R., Piccioli P., Carta S., Delfino L., Castellani P., Rubartelli A. (2014) TLR costimulation causes oxidative stress with unbalance of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine production. J. Immunol. 192, 5373–5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kastner D. L. (2005) Hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2005, 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masters S. L., Simon A., Aksentijevich I., Kastner D. L. (2009) Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease (*). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 621–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savic S., Dickie L. J., Wittmann M., McDermott M. F. (2012) Autoinflammatory syndromes and cellular responses to stress: pathophysiology, diagnosis and new treatment perspectives. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 26, 505–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubartelli A. (2014) Autoinflammatory diseases. Immunol. Lett. 161, 226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman H. M., Mueller J. L., Broide D. H., Wanderer A. A., Kolodner R. D. (2001) Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat. Genet. 29, 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldmann J., Prieur A. M., Quartier P., Berquin P., Certain S., Cortis E., Teillac-Hamel D., Fischer A., de Saint Basile G. (2002) Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agostini L., Martinon F., Burns K., McDermott M. F., Hawkins P. N., Tschopp J. (2004) NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity 20, 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aksentijevich I., Nowak M., Mallah M., Chae J. J., Watford W. T., Hofmann S. R., Stein L., Russo R., Goldsmith D., Dent P., Rosenberg H. F., Austin F., Remmers E. F., Balow J. E. Jr., Rosenzweig S., Komarow H., Shoham N. G., Wood G., Jones J., Mangra N., Carrero H., Adams B. S., Moore T. L., Schikler K., Hoffman H., Lovell D. J., Lipnick R., Barron K., O’Shea J. J., Kastner D. L., Goldbach-Mansky R. (2002) De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 46, 3340–3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldbach-Mansky R., Dailey N. J., Canna S. W., Gelabert A., Jones J., Rubin B. I., Kim H. J., Brewer C., Zalewski C., Wiggs E., Hill S., Turner M. L., Karp B. I., Aksentijevich I., Pucino F., Penzak S. R., Haverkamp M. H., Stein L., Adams B. S., Moore T. L., Fuhlbrigge R. C., Shaham B., Jarvis J. N., O’Neil K., Vehe R. K., Beitz L. O., Gardner G., Hannan W. P., Warren R. W., Horn W., Cole J. L., Paul S. M., Hawkins P. N., Pham T. H., Snyder C., Wesley R. A., Hoffmann S. C., Holland S. M., Butman J. A., Kastner D. L. (2006) Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 581–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gattorno M., Tassi S., Carta S., Delfino L., Ferlito F., Pelagatti M. A., D’Osualdo A., Buoncompagni A., Alpigiani M. G., Alessio M., Martini A., Rubartelli A. (2007) Pattern of interleukin-1beta secretion in response to lipopolysaccharide and ATP before and after interleukin-1 blockade in patients with CIAS1 mutations. Arthritis Rheum. 56, 3138–3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinarello C. A. (2011) Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 117, 3720–3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinarello C. A. (2000) The role of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in blocking inflammation mediated by interleukin-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 732–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozaki E., Campbell M., Doyle S. L. (2015) Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammatory diseases: current perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 8, 15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Santo E., Benigni F., Agnello D., Sipe J. D., Ghezzi P. (1999) Peripheral effects of centrally administered interleukin-1beta in mice in relation to its clearance from the brain into the blood and tissue distribution. Neuroimmunomodulation 6, 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aksentijevich I., Masters S. L., Ferguson P. J., Dancey P., Frenkel J., van Royen-Kerkhoff A., Laxer R., Tedgård U., Cowen E. W., Pham T. H., Booty M., Estes J. D., Sandler N. G., Plass N., Stone D. L., Turner M. L., Hill S., Butman J. A., Schneider R., Babyn P., El-Shanti H. I., Pope E., Barron K., Bing X., Laurence A., Lee C. C., Chapelle D., Clarke G. I., Ohson K., Nicholson M., Gadina M., Yang B., Korman B. D., Gregersen P. K., van Hagen P. M., Hak A. E., Huizing M., Rahman P., Douek D. C., Remmers E. F., Kastner D. L., Goldbach-Mansky R. (2009) An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 2426–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubartelli A., Cozzolino F., Talio M., Sitia R. (1990) A novel secretory pathway for interleukin-1 beta, a protein lacking a signal sequence. EMBO J. 9, 1503–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinon F., Burns K., Tschopp J. (2002) The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol. Cell 10, 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perregaux D. G., McNiff P., Laliberte R., Conklyn M., Gabel C. A. (2000) ATP acts as an agonist to promote stimulus-induced secretion of IL-1 beta and IL-18 in human blood. J. Immunol. 165, 4615–4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrei C., Dazzi C., Lotti L., Torrisi M. R., Chimini G., Rubartelli A. (1999) The secretory route of the leaderless protein interleukin 1beta involves exocytosis of endolysosome-related vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 1463–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrei C., Margiocco P., Poggi A., Lotti L. V., Torrisi M. R., Rubartelli A. (2004) Phospholipases C and A2 control lysosome-mediated IL-1 beta secretion: Implications for inflammatory processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9745–9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauernfeind F., Ablasser A., Bartok E., Kim S., Schmid-Burgk J., Cavlar T., Hornung V. (2011) Inflammasomes: current understanding and open questions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 765–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathinam V. A., Vanaja S. K., Fitzgerald K. A. (2012) Regulation of inflammasome signaling. Nat. Immunol. 13, 333–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinon F., Mayor A., Tschopp J. (2009) The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 229–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robbins G. R., Wen H., Ting J. P. (2014) Inflammasomes and metabolic disorders: old genes in modern diseases. Mol. Cell 54, 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dostert C., Pétrilli V., Van Bruggen R., Steele C., Mossman B. T., Tschopp J. (2008) Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science 320, 674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halle A., Hornung V., Petzold G. C., Stewart C. R., Monks B. G., Reinheckel T., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E., Moore K. J., Golenbock D. T. (2008) The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat. Immunol. 9, 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K. J., Sirois C. M., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F. G., Abela G. S., Franchi L., Nuñez G., Schnurr M., Espevik T., Lien E., Fitzgerald K. A., Rock K. L., Moore K. J., Wright S. D., Hornung V., Latz E. (2010) NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464, 1357–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gombault A., Baron L., Couillin I. (2012) ATP release and purinergic signaling in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front. Immunol. 3, 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lazarowski E. R., Boucher R. C., Harden T. K. (2003) Mechanisms of release of nucleotides and integration of their action as P2X- and P2Y-receptor activating molecules. Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 785–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Praetorius H. A., Leipziger J. (2009) ATP release from non-excitable cells. Purinergic Signal. 5, 433–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di Virgilio F. (2007) Liaisons dangereuses: P2X(7) and the inflammasome. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Netea M. G., Nold-Petry C. A., Nold M. F., Joosten L. A., Opitz B., van der Meer J. H., van de Veerdonk F. L., Ferwerda G., Heinhuis B., Devesa I., Funk C. J., Mason R. J., Kullberg B. J., Rubartelli A., van der Meer J. W., Dinarello C. A. (2009) Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1beta in monocytes and macrophages. Blood 113, 2324–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carta S., Tassi S., Pettinati I., Delfino L., Dinarello C. A., Rubartelli A. (2011) The rate of interleukin-1beta secretion in different myeloid cells varies with the extent of redox response to Toll-like receptor triggering. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27069–27080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piccini A., Carta S., Tassi S., Lasiglié D., Fossati G., Rubartelli A. (2008) ATP is released by monocytes stimulated with pathogen-sensing receptor ligands and induces IL-1β and IL-18 secretion in an autocrine way. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8067–8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antonioli L., Pacher P., Vizi E. S., Haskó G. (2013) CD39 and CD73 in immunity and inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 19, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carta S., Tassi S., Delfino L., Omenetti A., Raffa S., Torrisi M. R., Martini A., Gattorno M., Rubartelli A. (2012) Deficient production of IL-1 receptor antagonist and IL-6 coupled to oxidative stress in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome monocytes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 1577–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carta S., Penco F., Lavieri R., Martini A., Dinarello C. A., Gattorno M., Rubartelli A. (2015) Cell stress increases ATP release in NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated autoinflammatory diseases, resulting in cytokine imbalance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 2835–2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dinarello C. A. (2010) IL-1: discoveries, controversies and future directions. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carta S., Lavieri R., Rubartelli A. (2013) Different members of the IL-1 family come out in different ways: DAMPs vs. cytokines? Front. Immunol. 4, 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandinova A., Soldi R., Graziani I., Bagala C., Bellum S., Landriscina M., Tarantini F., Prudovsky I., Maciag T. (2003) S100A13 mediates the copper-dependent stress-induced release of IL-1alpha from both human U937 and murine NIH 3T3 cells. J. Cell Sci. 116, 2687–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sutterwala F. S., Ogura Y., Szczepanik M., Lara-Tejero M., Lichtenberger G. S., Grant E. P., Bertin J., Coyle A. J., Galán J. E., Askenase P. W., Flavell R. A. (2006) Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity 24, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gross O., Yazdi A. S., Thomas C. J., Masin M., Heinz L. X., Guarda G., Quadroni M., Drexler S. K., Tschopp J. (2012) Inflammasome activators induce interleukin-1α secretion via distinct pathways with differential requirement for the protease function of caspase-1. Immunity 36, 388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scheller J., Chalaris A., Schmidt-Arras D., Rose-John S. (2011) The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 878–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lasigliè D., Traggiai E., Federici S., Alessio M., Buoncompagni A., Accogli A., Chiesa S., Penco F., Martini A., Gattorno M. (2011) Role of IL-1 beta in the development of human T(H)17 cells: lesson from NLRP3 mutated patients. PLoS One 6, e20014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanaka T., Narazaki M., Kishimoto T. (2011) Anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. FEBS Lett. 585, 3699–3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Domercq M., Perez-Samartin A., Aparicio D., Alberdi E., Pampliega O., Matute C. (2010) P2X7 receptors mediate ischemic damage to oligodendrocytes. Glia 58, 730–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Onami K., Kimura Y., Ito Y., Yamauchi T., Yamasaki K., Aiba S. (2014) Nonmetal haptens induce ATP release from keratinocytes through opening of pannexin hemichannels by reactive oxygen species. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 1951–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baranova A., Ivanov D., Petrash N., Pestova A., Skoblov M., Kelmanson I., Shagin D., Nazarenko S., Geraymovych E., Litvin O., Tiunova A., Born T. L., Usman N., Staroverov D., Lukyanov S., Panchin Y. (2004) The mammalian pannexin family is homologous to the invertebrate innexin gap junction proteins. Genomics 83, 706–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qu Y., Misaghi S., Newton K., Gilmour L. L., Louie S., Cupp J. E., Dubyak G. R., Hackos D., Dixit V. M. (2011) Pannexin-1 is required for ATP release during apoptosis but not for inflammasome activation. J. Immunol. 186, 6553–6561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pelegrin P., Surprenant A. (2006) Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 25, 5071–5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simon A., Park H., Maddipati R., Lobito A. A., Bulua A. C., Jackson A. J., Chae J. J., Ettinger R., de Koning H. D., Cruz A. C., Kastner D. L., Komarow H., Siegel R. M. (2010) Concerted action of wild-type and mutant TNF receptors enhances inflammation in TNF receptor 1-associated periodic fever syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9801–9806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Omenetti A., Carta S., Delfino L., Martini A., Gattorno M., Rubartelli A. (2014) Increased NLRP3-dependent interleukin 1β secretion in patients with familial Mediterranean fever: correlation with MEFV genotype. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borghini S., Tassi S., Chiesa S., Caroli F., Carta S., Caorsi R., Fiore M., Delfino L., Lasigliè D., Ferraris C., Traggiai E., Di Duca M., Santamaria G., D’Osualdo A., Tosca M., Martini A., Ceccherini I., Rubartelli A., Gattorno M. (2011) Clinical presentation and pathogenesis of cold-induced autoinflammatory disease in a family with recurrence of an NLRP12 mutation. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 830–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rubartelli A., Gattorno M., Netea M. G., Dinarello C. A. (2011) Interplay between redox status and inflammasome activation. Trends Immunol. 32, 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shenton D., Smirnova J. B., Selley J. N., Carroll K., Hubbard S. J., Pavitt G. D., Ashe M. P., Grant C. M. (2006) Global translational responses to oxidative stress impact upon multiple levels of protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29011–29021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dalton L. E., Healey E., Irving J., Marciniak S. J. (2012) Phosphoproteins in stress-induced disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 106, 189–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fukumoto T., Matsukawa A., Ohkawara S., Takagi K., Yoshinaga M. (1996) Administration of neutralizing antibody against rabbit IL-1 receptor antagonist exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced arthritis in rabbits. Inflamm. Res. 45, 479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garlanda C., Dinarello C. A., Mantovani A. (2013) The interleukin-1 family: back to the future. Immunity 39, 1003–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Muralidharan S., Mandrekar P. (2013) Cellular stress response and innate immune signaling: integrating pathways in host defense and inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 94, 1167–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alkanani A. K., Rewers M., Dong F., Waugh K., Gottlieb P. A., Zipris D. (2012) Dysregulated Toll-like receptor-induced interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 responses in subjects at risk for the development of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 61, 2525–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chaudhry H., Zhou J., Zhong Y., Ali M. M., McGuire F., Nagarkatti P. S., Nagarkatti M. (2013) Role of cytokines as a double-edged sword in sepsis. In Vivo 27, 669–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brealey D., Brand M., Hargreaves I., Heales S., Land J., Smolenski R., Davies N. A., Cooper C. E., Singer M. (2002) Association between mitochondrial dysfunction and severity and outcome of septic shock. Lancet 360, 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adrie C., Bachelet M., Vayssier-Taussat M., Russo-Marie F., Bouchaert I., Adib-Conquy M., Cavaillon J. M., Pinsky M. R., Dhainaut J. F., Polla B. S. (2001) Mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis peripheral blood monocytes in severe human sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 164, 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shang L., Daubeuf B., Triantafilou M., Olden R., Dépis F., Raby A. C., Herren S., Dos Santos A., Malinge P., Dunn-Siegrist I., Benmkaddem S., Geinoz A., Magistrelli G., Rousseau F., Buatois V., Salgado-Pires S., Reith W., Monteiro R., Pugin J., Leger O., Ferlin W., Kosco-Vilbois M., Triantafilou K., Elson G. (2014) Selective antibody intervention of Toll-like receptor 4 activation through Fc γ receptor tethering. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 15309–15318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cauwels A., Rogge E., Vandendriessche B., Shiva S., Brouckaert P. (2014) Extracellular ATP drives systemic inflammation, tissue damage and mortality. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]