Abstract

Purpose: Assessment of ocular involvement in transthyretin-related familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy (FAP) in a large cohort of Portuguese patients.

Methods: We reviewed the medical records of 513 Portuguese FAP mutation carriers, at the Ophthalmology Service, Centro Hospitalar do Porto, between 1 January 2008 and 31 January 2013. Abnormal conjunctiva vessels (ACV), Schirmer test, tear break-up time (TBUT), amyloid deposition on the iris (DAI), scalloped iris, amyloid deposition on the anterior capsule of the lens (DAL), vitreous amyloidosis, retinal amyloid angiopathy and glaucoma were evaluated and registered.

Results: Of the 513 carriers, 477 (93%) had clinical systemic disease with a median duration of 9.3 (5.1–13.7) years and 247 were men. Of these, 343 (72%) had been liver transplanted, on median of 6.6 (3.3–10.8) years before inclusion in this study. No ocular abnormalities were identified in the asymptomatic carriers (7%). The abnormalities observed with decreasing frequency were abnormal TBUT (379 patients, 79.5%, 751 eyes), abnormal Schirmer test (320 patients, 67%, 635 eyes), DAI (183 patients, 38.4%, 350 eyes), DAL (157 patients, 32.9%, 308 eyes), scalloped iris (133 patients, 27.9%, 238 eyes), glaucoma (97 patients, 20%, 165 eyes), vitreous amyloidosis (83 patients, 17.4%, 139 eyes), ACV (68 patients, 14%, 136 eyes) and amyloidotic retinal angiopathy (21 patients, 4%, 32 eyes).

Patients with abnormal Schirmer test (p < 0.001), scalloped iris (p = 0.006) and vitreous amyloidosis (p = 0.007) were significantly older than the others. According to their age of onset of systemic disease, the patients have been split into early-onset (<40 years old), intermediate-onset (40–50 years old), late onset (>50 years old) and asymptomatic carriers. We observed a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of ACV (p = 0.045) and of an abnormal Schirmer test (p = 0.004) between groups. Transplanted patients have a significantly higher prevalence of DAI (p = 0.001), DAL (p = 0.009) and vitreous amyloidosis (p = 0.025) than non-transplanted patients. Of the 165 eyes with glaucoma, 92.1% had scalloped iris (p < 0.001) and of 32 eyes with retinal amyloidotic angiopathy, 68.8% had vitreous amyloidosis (p < 0.001). All prevalences increased with time of disease. The earliest ocular manifestations were abnormal Schirmer test and abnormal TBUT (12% and 17% at 5 years of clinical disease) and the least prevalent was retinal amyloid angiopathy (8% at 15 years of clinical disease).

Conclusion: Ocular disorders in FAP patients are common, and their prevalence increases with disease duration. Prevalence is influenced by several factors, such as the age at onset of FAP and liver transplantation.

Keywords: Amyloid, amyloidosis, ATTR V30M, eye, familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy

Introduction

Transthyretin V30M-related familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy (FAP TTRV30M) is the most common neuropathic hereditary amyloidosis (ATTR), inherited in an autosomal dominant mode. The disease is caused by an unstable mutant transthyretin (TTR) protein that is deposited in different tissues and organs, including the eyes, as amyloid fibrils. The main clinical feature is a prominent peripheral polyneuropathy [1–3].

More than 100 point mutations in TTR have been reported, and more than 80 of these are associated with FAP [4]. In most of Portuguese FAP patients, the implicated TTR variant has a single amino acid substitution of methionine for valine at position 30 of the TTR molecule (TTR V30M). Apart from Portugal, which is the world’s largest focus of the ATTR V30M, this mutation is also common in Swedish and Japanese FAP patients.

Transthyretin is mainly produced by the liver, the rationale for liver transplantation as a crude attempt at “gene therapy”, an approach that has proven effective in reducing circulating mutant transthyretin levels. In fact, TTR is also produced by the retina and the choroid plexus, sources of mutant TTR not interrupted by liver transplantation. Several ocular complications associated with amyloid deposition, such as abnormal conjunctiva vessels, dry eye, amyloid deposition on the anterior surface of the lens and on the pupil border, scalloped iris, glaucoma and vitreous opacities, can still occur after liver transplantation in FAP patients, and their prevalence increases over time [5–15].

FAP patients are usually classified as presenting an early-onset disease (onset before 50 years of age) or late-onset disease (onset after 50 years of age). Early onset is associated with a more aggressive, rapidly progressing disease, especially if symptoms appear before 40 years of age [16]. Most Portuguese FAP patients are early-onset cases, with a worse prognosis regarding the severity of symptoms and an expected survival of 10 to 15 years. Patients who manifest the disease between 40 and 50 years of age appear to have an intermediate evolution between the two classically described groups.

Liver transplantation was the first therapy that interrupts the progression of the disease and improve survival and quality of life [17]. However, the ocular synthesis of mutant TTR continues after liver transplantation, and mutant TTR has been detected in aqueous humour and vitreous of liver transplanted FAP patients [18,19]. Due to the prolonged survival granted by transplantation, ocular disease has a higher probability to occur, and there is evidence that liver transplantation may even hasten its appearance [20].

In order to characterize the ocular manifestations in FAP TTR V30M Portuguese patients, we reviewed the medical records of 513 Portuguese TTR V30M carriers, namely the data of the first evaluation at our Ophthalmology Service, between 1 January 2008 and 31 January 2013.

Material and methods

This study was a cross-sectional non-interventional survey based on the medical records of first ophthalmological evaluations. Study protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centro Hospitalar do Porto and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Patients

The study included a retrospective cohort of 513 consecutive patients, 52% men, and median age: 44.5 (38.4–51.5) years old, examined for ocular abnormalities at the Ophthalmology Service of Centro Hospitalar do Porto. All patients had the TTR V30M mutation confirmed by genetic analysis and were referenced to our outpatient ophthalmology clinic from all over the country. All of them were evaluated independently for the presence of ocular complaints, by the same senior ophthalmologist, in the same office space and with the same ophthalmic equipment, from January 2008 to January 2013. For comparative analysis, the patients were divided into four groups according to their onset of systemic disease: early-onset disease (< 40 years old, 346 patients), intermediate-onset disease (40–50 years old, 64 patients), late-onset disease (>50 years old, 67 patients) and asymptomatic carriers of the mutation (36 patients). The demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic data of 513 TTR V30M carriers (477 symptomatic patients).

| TTR V30M carriers (n) | 513 (1026 eyes) |

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 44.5 (38.4–51.5) |

| Male, gender (n, %) | 267 (52%) |

| Symptomatic patients (n) | 477 (954 eyes) |

| Age at onset, years (median, IQR) | 33 (29–40) |

| Onset <40 years (patients/eyes) | 346 / 692 |

| Onset >40<50 years (patients/eyes) | 64 / 128 |

| Onset > 50 years (patients/eyes) | 67 / 134 |

| Disease evolution time (years–median) | 9.3 (5.1–13.7) |

| Post-transplant follow-up (years–median) | 6.6 (3.3–10.8) |

| Affected father | |

| Men (n, %) | 86 (18.8%) |

| Age at onset of symptoms, years (median, IQR) | 35 (30–45) |

| Affected mother | |

| Men (n, %) | 139 (29.1%) |

| Age at onset of symptoms, years (median, IQR) | 33 (27–37) |

| Transmitting parent unknown or both affected (n) | 26 |

| Transplanted patients (n, %) | 343 (72%) |

For each patient, nine distinct FAP-related ocular manifestations were sought and evaluated: ACV, Schirmer test, tear break-up time (TBUT), amyloid deposition on the iris (DAI), scalloped iris, amyloid deposition on the anterior capsule of the lens (DAL), vitreous amyloidosis, retinal amyloid angiopathy and glaucoma. The presence of ACV, DAL and iris involvement (DAI and/or scalloped iris) was evaluated by slit-lamp examination. ACV were found mainly in the limbal area and typically appear as vascular fusiform dilatation. Lacrimal function was measured using the Schirmer test without anesthesia and TBUT. Schirmer test used paper strips (Schirmer-Plus) inserted in the temporal one-third of the lower eyelid and kept for 5 min with closed eyes. The paper was then removed and the amount of moisture was measured in millimeters. It was considered abnormal, if it measures less than 10 mm. To measure TBUT, an eyedrop of Fluotest® was applied to the inferior conjunctiva and the tear film was observed under a slit lamp with a cobalt blue filter and the elapsed time, in seconds, was recorded before the initial break-up, rupture of the tear film or formation of dry spots. It was considered abnormal if less than 6 s. Glaucoma was identified by the presence of abnormalities in optic nerve and visual field, associated with an intra-ocular pressure level equal to or higher than 22 mm Hg, or were inferred from ongoing treatment with ocular hypotensive eyedrops and/or previous glaucoma surgery. To evaluate the vitreous and the retina, the pupil was dilated with one drop of topical tropicamide at 1% and observation was carried out after 30 min with a non-contact 90-D lens. Patients already vitrectomized for vitreous amyloidosis were also considered positive for vitreous amyloidosis. The presence of amyloidotic retinopathy is detected by peripheral retina observation or, in more severe cases, by iris rubeosis. In presence of amyloidotic retinopathy, retinal dot hemorrhages and vascular occlusion were observed, reaching up to 360 degrees of the peripheral retina. Fluorescein angiography of the peripheral retina is very helpful for the diagnosis. Due to retinal ischemia, laser photocoagulation is required for all ischemic area.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were described using median (interquartile range) and categorical data were expressed as number (frequencies). Data were compared using Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine significant associations between glaucoma and vitreous angiopathy and the other studied oculopathies. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS for Mac, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

In this study, in contrast to previous reports from other countries [21–25], no asymptomatic carrier presented any ocular FAP-related disorders (36 individuals, 72 eyes) and this group of TTR V30M carriers were excluded from further analysis.

Ocular involvement of FAP is typically asymmetrical. It was considered for statistical analysis that a patient had a specific FAP ocular manifestation, if one or both eyes were affected. The prevalence of each ocular manifestation is summarized in Table 2. The most prevalent extra-ocular FAP manifestation was the abnormal TBUT (379 patients, 79.5%, 751 eyes). The most common manifestation at the anterior segment was DAI (183 patients, 38.4%, 350 eyes) and at the posterior segment was glaucoma (97 patients, 20%, 165 eyes).

Table 2. Number of patients/eyes, prevalence and age of patients with or without ocular manifestations (median, IQR).

| Manifestation | Patients/eyes | Prevalence | Median age | IQR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACV | + | 68/136 | 14.3% | 44.5 | 40.0–49.3 | 0.793 |

| − | 409/818 | 44.5 | 38.1–52.0 | |||

| Schirmer test | + | 320/635 | 67% | 46.4 | 41.0–53.7 | <0.001 |

| − | 157/319 | 39.9 | 36.1–45.3 | |||

| TBUT | + | 379/751 | 79.5% | 44.6 | 38.9–51.2 | 0.859 |

| − | 98/203 | 43.1 | 38.0–54.0 | |||

| DAI | + | 183/350 | 38.4% | 46.1 | 40.8–52.9 | 0.007 |

| − | 294/604 | 42.8 | 37.7–50.6 | |||

| Scalloped Iris | + | 133/238 | 27.9% | 46.4 | 41.6–53.2 | 0.006 |

| − | 344/716 | 43.1 | 37.9–50.6 | |||

| DAL | + | 157/308 | 32.9% | 46.1 | 39.9–52.9 | 0.109 |

| − | 320/646 | 43.2 | 38.2–51.2 | |||

| Vitreous amyloidosis | + | 83/139 | 17.4% | 46.8 | 40.8–53.3 | 0.045 |

| − | 394/815 | 43.7 | 38.0–51.1 | |||

| Retinal angiopathy | + | 21/32 | 4.4% | 47.9 | 39.9–56.0 | 0.281 |

| − | 456/922 | 44.3 | 38.3–51.1 | |||

| Glaucoma | + | 97/165 | 20.3% | 46.2 | 40.3–53.3 | 0.079 |

| − | 380/789 | 43.8 | 38.2–50.6 |

Significant differences in median age of patients were observed for Schirmer test, deposition of amyloid on the iris (DAI), scalloped iris, and vitreous amyloidosis. No significant differences in median age of patients for abnormal conjunctiva vessel (ACV) tear break-up time (TBUT), deposition of amyloid on the anterior capsule of the lens (DAL), retinal angiopathy and glaucoma.

We observed that when the disease was inherited from the mother, the age of onset of FAP systemic symptoms was significantly earlier [median 33 (27–37) years versus median 35 (30–45) years, p < 0.001]. However, neither the gender of the ATTR V30M patient nor their affected parent had a significant impact on any of the studied ophthalmologic manifestations.

A statistically significant difference in the prevalence of ACV (p = 0.045) and abnormal Schirmer test (p = 0.004) was observed among the three groups with different age of onset of the disease. ACV were more prevalent in the intermediate-onset group (17.2%), followed by the early-onset group (15.6%) and by the late-onset group (4%). Abnormal Schirmer test was more prevalent in the late-onset group (80.6%), followed by intermediate-onset group (71.9%) and early-onset group (63.6%).

Comparing the prevalence of each manifestation in liver transplanted and non-transplanted FAP patients, we found a significantly higher prevalence of DAI (42.9% versus 26.9%, p = 0.001), scalloped iris (21.6% versus 30.3%, p = 0.05), DAL (23.9% versus 36.1%, p = 0.009) and vitreous amyloidosis (11.2% versus 19.8%, p = 0.025) in liver-transplanted FAP patients. No significant differences were found in the other studied manifestations. Glaucoma was positively associated with the presence of scalloped iris. From 165 eyes with glaucoma, 149 eyes (92.1%) presented scalloped iris, p < 0.001 (chi-squared test); univariate regression analysis was statistically significant (O.R. 15.041, I.C. 95% (5.345–42.328), p < 0.01).

A positive association was also observed between retinal amyloid angiopathy and vitreous amyloidosis. From 32 eyes with retinal amyloidotic angiopathy, 22 (69%) had vitreous amyloidosis, p < 0.001 (chi-squared test); univariate regression analysis was statistically significant (O.R. 6.902, I.C. 95% (2.129–22.373), p = 0.001).

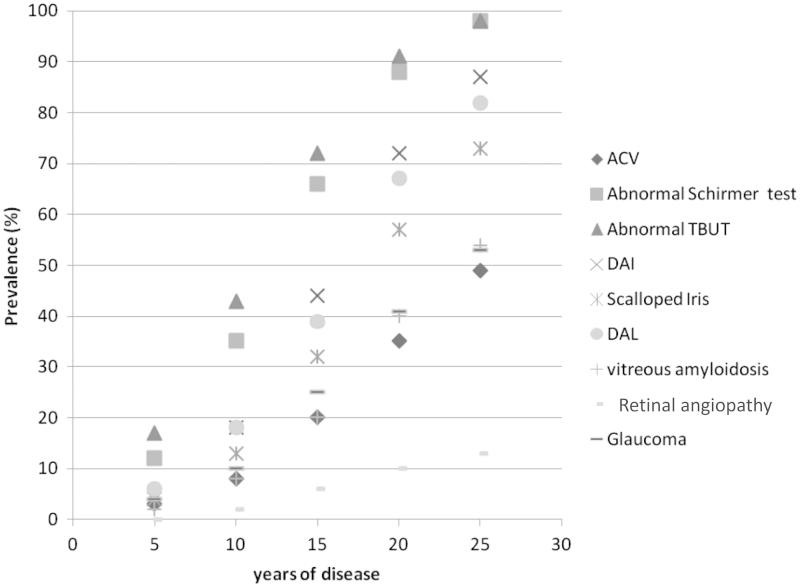

The prevalence of each ocular manifestation at 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 years of disease evolution are represented in Figure 1, which showed that the prevalence of all manifestations increases with duration of disease.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of each ocular manifestation at 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 years of disease. All prevalences increased with time. ACV, abnormal conjunctiva vessels; DAI, deposition of amyloid on the iris; DAL, deposition of amyloid on the lens.

In patients with 5 years of clinical disease, the most prevalent ocular manifestations were abnormal TBUT (17%) and abnormal Schirmer test (12%). All the other studied manifestations had a prevalence ≤6% and no patient had retinal amyloid angiopathy.

At 10 years of disease, all prevalences increased headed by the abnormal TBUT (43%) and the abnormal Schirmer test (35%). In this group, only 2% of patients presented retinal amyloid angiopathy.

In patients with 15 years of disease evolution, all ocular manifestations prevalences increased markedly, abnormal TBUT (72%) and abnormal Schirmer test (67%) were still the most prevalent.

Finally, after 20 years of clinical disease the prevalence of each symptom was: Abnormal TBUT – 91%, Abnormal Schirmer test – 88%, DAI – 72%, DAL – 67%, scalloped iris – 57%, glaucoma – 41%, vitreous amyloidosis – 40%, ACV – 35% and retinal amyloidotic angiopathy – 10%.

Discussion

TTR is widely distributed in ocular tissues and it has been identified in the corneal endothelium, lens capsule, iris epithelium, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), ciliary pigment epithelium (CPE) and retinal nerve fibers [25]. It is known that TTR is produced locally by RPE and CPE cells [26--28]. The progression of ocular disease after liver transplantation suggests that continued intra-ocular TTR production is relevant in this context.

The prevalence of the ocular manifestations was not similar between the three study groups. ACV were more prevalent in the intermediate-onset group. These abnormal vessels can be observed in diabetic and hypertensive patients, as well as in healthy individuals and, therefore they are not specific for the FAP. Despite not having clinical implications, they contribute to the red appearance conjunctiva in many FAP patients. Ando et al. described the ACV as more prevalent in early-onset disease patients and associated them to the neuropathy [6,7]. However, in early-onset disease Portuguese patients, ACV was neither the earliest nor the most frequent ocular manifestation (15.6%) and was even less prevalent in late-onset disease patients (4%). Other factors besides neuropathy are probably involved in its genesis.

Abnormal Schirmer test was commonly observed, with prevalences of 63.6% in early-onset disease group, 71.9% in intermediate-onset disease group and 80.6% in late-onset disease group. The increased prevalence of abnormal Schirmer test in the late-onset disease group is probably related to aging [29], to the neuropathy and the amyloid deposition in the lacrimal gland.

No significant difference between genders was observed for any of the studied ocular FAP manifestations. At least it might be expected to find differences in the dry eye parameters since, in the general population, dry eye is more prevalent in women [30]. The absence of this difference could be due to more severe neuropathy in males, nullifying the expected gender difference in the evaluated dry eye parameters [31]. Despite the known influence of the gender of parent transmitting on disease systemic manifestation of FAP, with a significantly earlier age of onset in those who inherited the illness from their mother, no differences were found for ophthalmologic manifestations.

After liver transplantation, it would be expected a reduction in prevalence of extra-ocular FAP manifestations: Schirmer test and TBUT (dry eye) and ACV due to removal of serum mutant TTR. In our study, no significant difference were found on abnormal Schirmer test, TBUT and ACV prevalences between transplanted and non-transplanted patients.

A significantly higher prevalence of DAI, on the capsule (DAL) and vitreous and of scalloped iris was observed in liver-transplanted patients. This unexpected negative effect of liver transplant was more evident in endocular manifestations, suggesting that continuous local production is implicated. The mutant TTR is unable to cross the blood–ocular barrier [32], and therefore, all endocular mutant TTR has local origin. The increased patient survival with liver transplantation allows with time appearance of these ocular changes, and explain, at least in part, their higher prevalence in transplanted patients. Furthermore, there might be a bias in the analysis if the non-transplanted patients had a more insidious and less aggressive disease, or other clinical problems, which could contribute to a more insidious disease. Further studies are needed to clarify this question.

Disease duration was an important factor in assessing the risk of oculopathy in FAP patients. The prevalence of ocular disease increases with time (Figure 1) and it is expected that a serious eye disease may affect all patients. The order of appearance of ocular abnormalities seems to be (1) abnormal TBUT (2) abnormal Schirmer test, (3) amyloid deposition on iris and anterior capsule, (4) ACV, (5) scalloped iris, (6) glaucoma, (7) vitreous amyloidosis and finally, (8) retinal amyloid angiopathy. The first ophthalmologic disorders are related to autonomic neuropathy and circulating TTR. Ocular changes related to the endocular TTR production appear later. The earliest manifestations of the endocular disease to appear are probably dependent on CPE TTR production, namely DAI, DAL and glaucoma (anterior segment), followed later by vitreous amyloidosis and retina angiopathy, apparently more dependent on RPE TTR production (posterior segment).

The presence of scalloped iris before the onset of glaucoma was noticed. In the present study, chi-square test and the univariate regression analysis corroborated a strong association between glaucoma and scalloped iris. In the absence of scalloped iris, the risk for developing glaucoma is probably similar to the general population. The appearance of scalloped iris should be an indication to increase the frequency of intra-ocular pressure surveillance and look for glaucoma.

An association between vitreous amyloidosis and retinal angiopathy also seems to occur. The appearance and rapid progression of amyloidotic retinal angiopathy after vitreous amyloidosis removal (unpublished data) suggests that impregnation of the small terminal vessels in the peripheral retina with amyloid comes from the vitreous to the lumen of the vessel and may cause progressive changes of the vessel wall and subsequent obliteration. Thus, it presents a very similar pathophysiology to cerebral amyloid angiopathy that also continues to progress after liver transplantation. Both seem to be dependent of the vitreous and cerebrospinal fluid mutant TTR, and not of systemic mutant TTR.

Pathological ocular changes in FAP patients are highly prevalent and became more frequent with time. The age of onset of FAP influences the expression of ocular disease and liver transplantation, probably to change the natural course of ocular disease. The longer survival of transplanted FAP patients is by itself a risk factor for eye disease development and, therefore, all FAP patients, transplanted or not, require a life-long ophthalmologic follow-up with adjusted intervals to the different manifestations observed, in order to maintain an optimal visual function and a good quality of life provided by the liver transplantation.

Conclusion

Our data indicate that the ophthalmologic follow-up of liver transplanted and non-transplanted ATTR V30M patients should be the same. We suggest the following protocol: first ophthalmologic examination at the time the genetic diagnosis and, thereafter, repeated every 2 years in asymptomatic carriers and annually in symptomatic patients. After appearance of oculopathy, the frequency of ophthalmologic evaluation should be annually for ACV, and every 6-month for lacrimal dysfunction (after the control), DAI and DAL. For scalloped iris, glaucoma (after the control), vitreous amyloidosis (after surgery, if necessary) and retinal angiopathy (after LASER therapy) the ophthalmologic follow-up should be for every 3 months.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACV

abnormal conjunctiva vessels, scalloped iris

- ATTR V30M

amyloidosis TTR V30M related

- DAI

amyloid deposition on the iris

- DAL

amyloid deposition on the anterior capsule of the lens

- CPE

ciliary pigment epithelium

- FAP

familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy

- TBUT

tear break-up time

- TTR

transthyretin

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

References

- Andrade C. A peculiar form of peripheral neuropathy; familiar atypical generalized amyloidosis with special involvement of the peripheral nerves. Brain. 1952;75:408–27. doi: 10.1093/brain/75.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva MJ, Birken S, Costa PP, Goodman DS. Family studies of the genetic abnormality in transthyretin (prealbumin) in Portuguese patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1984;435:86–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb13742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho T, Sousa A, Lourenço E, Ramalheira J. A study of 159 Portuguese patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP) whose parents were both unaffected. J Med Genet. 1994;31:293–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutations in Hereditary Amyloidosis. Available from: www.amyloidosismutations.com

- Falls HF, Jackson J, Carey JH, Rukavina JG, Block WD. Ocular manifestations of hereditary primary systemic amyloidosis. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1955;54:660–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1955.00930020666004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando E, Ando Y, Maruoka S, Sakai Y, Watanabe S, Yamashita R, Okamura R, et al. Ocular microangiopathy in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, type I. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992;230:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00166754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando E, Ando Y, Okamura R, Uchino M, Ando M, Negi A. Ocular manifestations of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy type I: long-term follow up. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:295–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman HE. Primary familial amyloidosis. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958;60:1036–43. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940081056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munar-Qués M, Salva-Ladaria L, Mulet-Perera P, Solé M, López-Andreu FR, Saraiva MJ. Vitreous amyloidosis after liver transplantation in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy: ocular synthesis of mutant transthyretin. Amyloid. 2000;7:266–9. doi: 10.3109/13506120009146440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirão M, Matos E, Beirâo I, Costa PP, Torres P. Anticipation of presbyopia in Portuguese familial amyloidosis ATTR V30M. Amyloid. 2011;18:92–7. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.576719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandgren O, Kjellgren D, Suhr OB. Ocular manifestations in liver transplant recipients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86:520–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirão M, Matos E, Reis R, Beirão I, Costa PP, Torres P. Spatial visual contrast sensitivity in liver transplanted Portuguese familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (ATTR V30M) patients. Amyloid. 2012;19:152–5. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.712075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara R, Kawaji T, Ando E, Ohya Y, Ando Y, Tanihara H. Impact of liver transplantation on transthyretin-related ocular amyloidosis in Japanese patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:206–10. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirão NM, Matos ME, Meneres MJ, Beirão IM, Costa PP, Torres PA. Vitreous surgery impact in glaucoma development in liver transplanted familial amyloidosis ATTR V30M Portuguese patients. Amyloid. 2012;19:146–51. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.710669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirão JM, Matos ME, Beirão IB, Costa PP, Torres PA. Topical cyclosporine for severe dry eye disease in liver-transplanted Portuguese patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (ATTRV30M) Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23:156–63. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos C, Coelho T, Alves-Ferreira M, Martins-da-Silva A, Sequeiros J, Mendonça D, Sousa A. Overcoming artefact: anticipation in 284 Portuguese kindreds with familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) ATTRV30M. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:326–30. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Ando Y, Okamoto S, Misumi Y, Hirahara T, Ueda M, Obayashi K, et al. Long-term survival after liver transplantation in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2012;78:637–43. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318248df18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraoka K, Ando Y, Ando E, Sun X, Nakamura M, Terazaki H, Misumi S, et al. Presence of variant transthyretin in aqueous humor of a patient with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy after liver transplantation. Amyloid. 2002;9:247–51. doi: 10.3109/13506120209114101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y, Terazaki H, Nakamura M, Ando E, Haraoka K, Yamashita T, Ueda M, et al. A different amyloid formation mechanism: de novo oculoleptomeningeal amyloid deposits after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77:345–9. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000111516.60013.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara R, Kawaji T, Ando E, Ohya Y, Ando Y, Tanihara H. Impact of liver transplantation on transthyretin-related ocular amyloidosis in Japanese patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:206–10. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador F, Mateo C, Alegre J, Reventos A, García-Arumi J, Corcostegui B. Vitreous amyloidosis without systemic or familial involvement. Int Ophthalmol. 1993;17:355–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00915743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaji T, Ando Y, Ando E, Nakamura M, Hirata A, Tanihara H. A case of vitreous amyloidosis without systemic symptoms in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Amyloid. 2004;11:257–9. doi: 10.1080/13506120400015580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry AP, Lieberman TW. Bilateral amyloidosis of the vitreous body without systemic involvement. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94:982–91. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1976.03910030494012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau A, Kaswin G, Adams D, Cauquil C, Théaudin M, Mincheva Z, M'garrech M, et al. Ocular involvement in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2013;36:779–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Lu L, Li YH, Zhong H, Fang W, Zhang L, Li WL. Transthyretin Arg-83 mutation in vitreous amyloidosis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2011;4:329–31. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2011.03.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwork AJ, Cavallaro T, Martone RL, Goodman DS, Schon EA, Herbert J. Distribution of transthyretin in the rat eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro T, Martone RL, Dwork AJ, Schon EA, Herbert J. The retinal pigment epithelium is the unique site of transthyretin synthesis in the rat eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaji T, Ando Y, Nakamura M, Yamamoto K, Ando E, Takano A, Inomata Y, et al. Transthyretin synthesis in rabbit ciliary pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:306–12. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney DF, Millar TJ, Raju SR. Tear film stability: a review. Exp Eye Res. 2013;117:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malet F, Le Goff M, Colin J, Schweitzer C, Delyfer MN, Korobelnik JF, Rougier MB, et al. Dry eye disease in French elderly subjects: the Alienor Study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:429–36. doi: 10.1111/aos.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Duarte A, Soto KC, Martínez-Baños D, Arteaga-Vazquez J, Barrera F, Berenguer-Sanchez M, Cantu-Brito C, et al. Familial amyloidosis with polyneuropathy associated with TTR Ser50Arg mutation. Amyloid. 2012;19:171–6. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.712925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirão JM, Moreira LV, Lacerda PC, Vitorino RP, Beirão IB, Torres PA, Costa PP. Inability of mutant transthyretin V30M to cross the blood-eye barrier. Transplantation. 2012;94:e54–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318269e6d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]