Abstract

β-1,3:1,4-Glucan is a major cell wall component accumulating in endosperm and young tissues in grasses. The mixed linkage glucan is a linear polysaccharide mainly consisting of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units linked through single β-1,3-glucosidic linkages, but it also contains minor structures such as cellobiosyl units. In this study, we examined the action of an endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase from Trichoderma sp. on a minor structure in barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan. To find the minor structure on which the endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase acts, we prepared oligosaccharides from barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan by endo-β-1,4-glucanase digestion followed by purification by gel permeation and paper chromatography. The endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase appeared to hydrolyze an oligosaccharide with degree of polymerization 5, designated C5-b. Based on matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) time-of-flight (ToF)/ToF-mass spectrometry (MS)/MS analysis, C5-b was identified as β-Glc-1,3-β-Glc-1,4-β-Glc-1,3-β-Glc-1,4-Glc including a cellobiosyl unit. The results indicate that a type of endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase acts on the cellobiosyl units of barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan in an endo-manner.

Key words: barley; cellobiosyl unit; endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase: β-1,3:1,4-glucan; MALDI-ToF/ToF-/MS/MS

β-1,3:1,4-Glucan is a linear polysaccharide relatively abundant in young tissues and endosperm of grasses. 1 ) Although the mixed linkaged β-glucan does not exist in dicotyledonous plants, it has been also found in lichens such as Cetralia islandica and recently in horsetails (Equisetopsida). 2,3 ) β-1,3:1,4-Glucan is mainly consisted of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units linked through single β-1,3-glucosidic linkages, though the proportion of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units varies depending on the plant species. β-1,3:1,4-Glucan has also minor structures that are cellobiosyl units and long β-1,4-glucosyl stretches linked through a single β-1,3-glucosidic linkage, and continuous β-1,3-glucosyl residues. 4,5 ) The activity of β-1,3:1,4-glucan synthase has been seen in microsomal fractions prepared from young seedlings and endosperm in barley, maize, and rice. 6–8 ) To date, two glycosyltransferases, cellulose synthase-like F (CslF) and H (CslH), have been identified as components required for the synthesis of β-1,3:1,4-glucan in Poaceae. 9,10 ) However, it is still unknown whether β-1,3- and β-1,4-glucosyl residues are synthesized by single glycosyltransferase. In addition, the synthesis of cellotriosyl units was selectively inhibited by {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid}, indicating the presence of at least two different glycosyltransferases synthesizing odd-numbered and even-numbered cellooligosaccharide units. 11,12 ) However, the precise mechanism for the synthesis of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units and minor structures remains to be clarified.

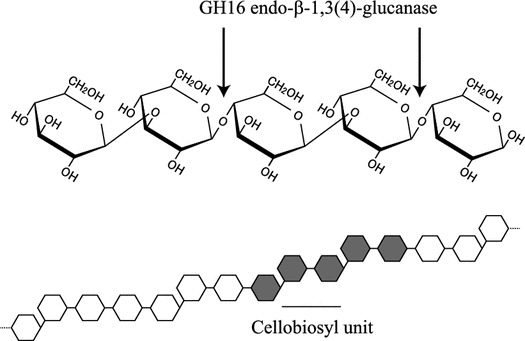

β-1,3:1,4-Glucan undergoes degradation by endogenous hydrolases in young tissues and germinating seeds of Poaceae plants. 13,14 ) Endo-β-1,3:1,4-glucanase (EC 3.2.1.73) of Poaceae plants belonging to glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 17 is an enzyme specifically hydrolyzing the β-glucan in an endo-manner. 15 ) Higher plants also possess GH9 endo-β-1,4-glucanases (EC 3.2.1.4, cellulase) acting on the β-glucan in endo-manner. 16,17 ) In addition to the endo-acting enzymes, β-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.21) and exo-β-glucanase (β-glucan exohydrolase, EC 3.2.1.58) hydrolyzing both β-1,3- and β-1,4-glucosidic linkages in exo-manner participate in the hydrolysis of β-1,3:1,4-glucan. 18,19 ) β-1,3:1,4-Glucan is also degraded by various enzymes secreted by fungi and bacteria in nature. Together with endo-β-1,3:1,4-glucanase and endo-β-1,4-glucanase, 4 ) endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase (EC 3.2.1.6) takes part in the hydrolysis of β-1,3:1,4-glucan as an endo-acting enzyme. The enzyme has substrate specificity distinct from endo-β-1,3:1,4-glucanase and endo-β-1,4-glucanase, as it acts on both of β-1,3:1,4-glucan and β-1,3-glucan. Actually, an endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium, PcLam16A, belonging to GH16 family acts on lichenin, β-1,3:1,4-glucan from C. islandica, liberating β-Glc-1,4-β-Glc-1,3-Glc (G4G3G) and also on β-1,3:1,6-glucan releasing G6G3G3G as the main products, respectively. 20 ) On the basis of three-dimensional (3-D) structure, the enzyme was revealed to accommodate both of β-1,3:1,6-glucan and β-1,3:1,4-glucan in its substrate-binding cleft by using different subsites +2, while it specifically recognizes the β-1,3-glucosidic linkage between the subsite −1 and −2. 21 ) It is probable that endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanases act not only on cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units but also cellobiosyl unit in β-1,3:1,4-glucan, but the action on cellobiosyl unit structure using a specific oligosaccharide remains to be examined.

In this study, we report that a GH16 endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase from Trichoderma sp. can act on the cellobiosyl unit in barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan, while GH12 endo-β-1,4-glucanase from Aspergilus niger and GH17 endo-β-1,3-glucanase from barley cannot. The possible mechanism for the hydrolysis of the minor structure by the enzyme from Trichoderma sp. is discussed.

Materials and methods

Materials

Carboxymethyl (CM)-cellulose, cellooligosaccharides, β-1,3:1,4-glucan from barley (high, medium, and low viscosity), GH16 endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase from Trichoderma sp. (the commercial name is endo-β-1,3-glucanase), GH12 endo-β-1,4-glucanase (cellulase) from A. niger, and laminarioligosaccharides were purchased from Megazyme (Wicklow, Ireland). The purity of the enzymes was confirmed (Supplemental Fig. 1). Barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan, E70-S, was from ADEKA (Tokyo, Japan). Laminarin (β-1,3:1,6-glucan) from Laminaria digitata was from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Recombinant barley endo-β-1,3-glucanases belonging to GH17, GI (rGI), and rGII, 22 ) were expressed in Pichia pastoris and purified by conventional chromatography (Supplemental Information, Supplemental Fig. 1).

Measurement of enzyme activity by reducing sugar assay

The activities of enzymes were measured using reaction mixtures (0.1 mL) consisting of the enzyme, 0.1% (w/v) polysaccharide, and 200 mM acetate buffer, pH 5.0. After incubation at 37 °C for the appropriate reaction time, the liberated sugars were determined reductometrically by the method of Nelson 23 ) and Somogyi. 24 ) One unit of enzyme activity liberates 1 μmol of reducing sugar per min. The concentration of protein was determined by the method of Bradford 25 ) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Analysis of endo-manner action on β-glucan

Digestion of β-1,3:1,4-glucan with enzyme was performed using a reaction mixture (total volume, 1 mL) consisting of the enzyme, 0.3% (w/v) β-1,3:1,4-glucan, and 50 mM 3-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid-NaOH buffer (pH 6.5). The apparent molecular weight (M r) of the β-glucan was estimated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a Shimadzu LC-10 A (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) fitted with a refractive index detector (Shimadzu) and tandem columns (each 7.8 × 300 mm) of TSKgel G3000PWXL and G2500PWXL (Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan), equilibrated and eluted with 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min and at 40 °C. The void volume (V 0) and inner volume (V i) were determined with pullulan markers (Shodex Standard P-82; Showa Denko, Tokyo, Japan) and Glc.

Preparation of C5 oligosaccharides

One gram of barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan, E70-S, was digested with endo-β-1,4-glucanase from A. niger in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) at 37 °C for 24 h. The hydrolysate was lyophilized by freeze-dry and dissolved into 4 mL of water. Oligosaccharides released from the β-glucan were separated by gel permeation chromatography on a Bio-Gel P-2 column (26 mm × 925 mm, Bio-Rad). The V 0 and V i of the column were determined with dextran (Sigma) and Glc. Oligosaccharides were fractionated into C3, C4, and C5 fractions in order of increasing degree of polymerization (DP), which was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF-MS) with a Bruker AutoflexIII (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). C5 fraction was further fractionated into C5-a, -b, and -c by paper chromatography using Whatman 3MM filter paper with 6:4:3 (v/v/v) 1-butanol/pyridine/water (Supplemental Fig. 2). The sugar content of the fractions was determined by the phenol–sulfuric acid method using Glc as the standard. 26 )

Methylation analysis

For the analysis of sugar linkage, the oligosaccharide (approximately 100 μg) was subjected to the methylation analysis. Methylation was performed by the Hakomori method, 27 ) and the products were analyzed by gas liquid chromatography (GLC). GLC of neutral sugars as their alditol acetate derivatives was done with a Shimadzu gas chromatograph GC-6A equipped with a column (0.28 mm × 50 m) of Silar-10C, according to the method of Albersheim et al. 28 )

Action of enzymes on oligosaccharides

The action of the Trichoderma enzyme, rGI, and rGII on C4 and C5-b was analyzed using a reaction mixture (total volume, 20 μL) containing the enzyme, 0.1 mM oligosaccharide, and 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the sample was inactivated by heating. The reducing sugars liberated were coupled at their reducing terminals with p-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (ABEE) by the method of Matsuura and Imaoka. 29 ) The ABEE-derivatized sugars were analyzed on an HPLC system equipped with a TSKgel Amide-80 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm; Tosoh). The column was eluted with a linear gradient of CH3CN:water from 74:26 to 58:42 (v/v), for 40 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and 40 °C. ABEE sugars were monitored by a fluorescence detector model RF-10AXL at 305 nm (excitation) and 360 nm (emission).

Structural analysis of oligosaccharide

For MALDI-ToF/ToF-MS/MS, per-methylation of glycans was performed using the NaOH slurry method described by Ciucanu and Kerek 30 ) using 1 mL of methyl iodide (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). Dry samples were resuspended in 100 μL of methanol and were kept at room temperature for MALDI-ToF/ToF-MS/MS analysis. Per-methylated methanol dissolved samples (5 μL) were mixed with 5 μL of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix {10 mg/mL dissolved in 50% (v/v) methanol} and 1 μL of the mixture was spotted on a MALDI target plate and analyzed by MALDI-ToF/ToF-MS/MS (4700 proteomics analyzer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as previously described. 31 ) High-energy MALDI collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra were acquired with an average 10,000 laser shots/spectrum, using a high collision energy (1 kV). The oligosaccharide ions were allowed to collide in the CID cell with argon at a pressure of 2 × 10−6 Torr.

Polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis

Products from the C5-b oligosaccharide by the Trichoderma enzyme were analyzed by polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis (PACE). The derivatization of carbohydrates was performed according to previously developed protocols. 32 ) Carbohydrate electrophoresis and PACE gel scanning were performed as described by Goubet et al. 32 )

Results

Hydrolytic activity of endo-glucanases toward β-1,3:1,4-glucan

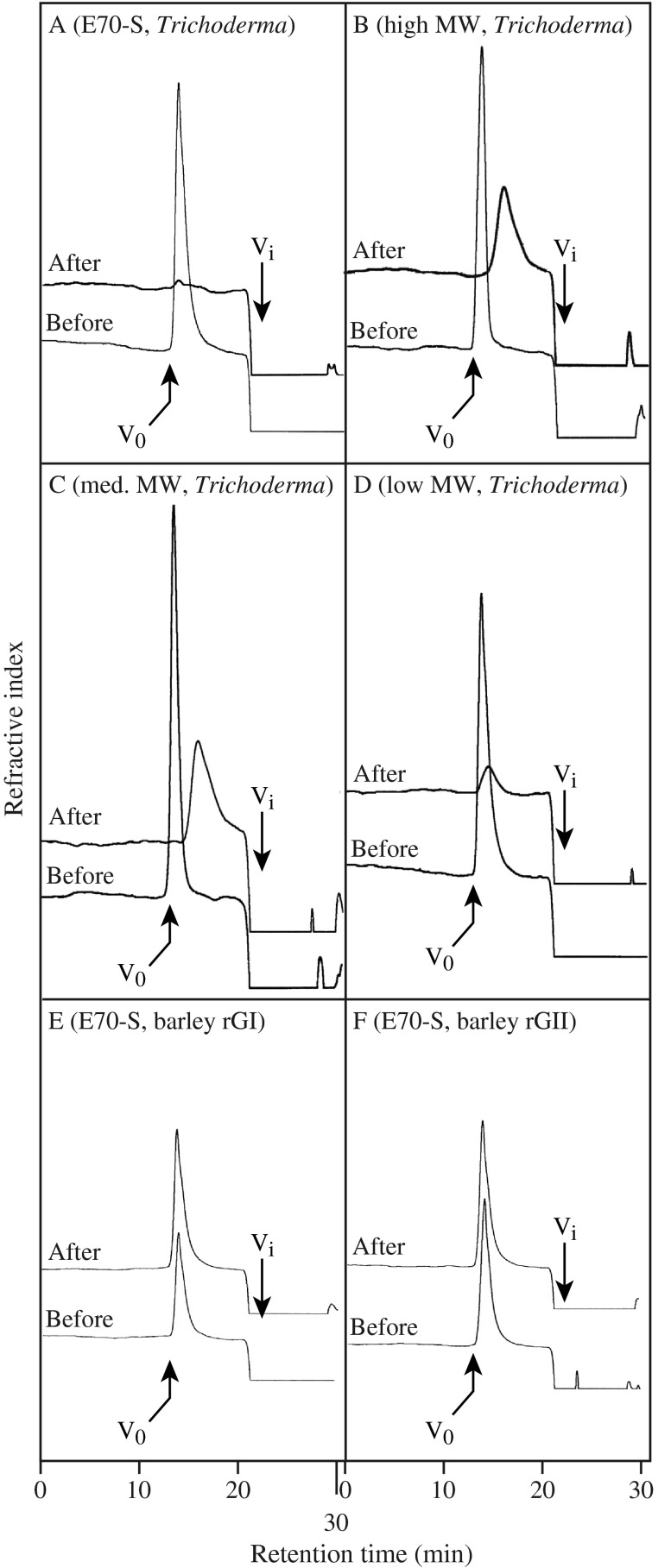

In this study, we analyzed the action of a commercial endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase from Trichoderma sp. belonging to GH16 family and two recombinant barley endo-β-1,3-glucanases belonging to GH17 family, rGI and rGII, 22 ) on β-1,3:1,4-glucan. The Trichoderma enzyme purchased from Megazyme was identified as GH16 enzyme by MLADI-ToF/ToF-MS/MS analysis (data not shown). The rGI and rGII were expressed in P. pastoris and purified by conventional chromatography to homogeneity (Supplemental Information, Supplemental Fig. 1). First, the substrate specificity of the Trichoderma endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase was confirmed by comparing with that of endo-β-1,3-glucanases rGI and rGII. The Trichoderma enzyme hydrolyzed laminarin, β-1,3:1,6-glucan from L. digitata, and barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan but hardly acted on CM-cellulose, proving that it has the characteristic of endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase (Table 1). On the other hand, rGI and rGII failed to act on β-1,3:1,4-glucan. In addition, the endo-manner action of the Trichoderma enzyme on β-1,3:1,4-glucan was also confirmed. Consistent with the activity toward β-1,3:1,4-glucan determined by the reducing sugar assay, the Trichoderma enzyme decreased the apparent M r of β-1,3:1,4-glucan, but rGI and rGII did not cause any change (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Substrate specificity of the enzymes.

| Substrate a | rGI | rGII | Trichoderma enzyme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laminarin (β-1,3:1,6-glucan) | 100 b | 100 | 100 |

| β-1,3:1,4-Glucan (high viscosity) | <0.1 | <0.1 | 41 |

| β-1,3:1,4-Glucan (medium viscosity) | <0.1 | <0.1 | 9 |

| β-1,3:1,4-Glucan (low viscosity) | <0.1 | <0.1 | 9 |

| CM-cellulose (β-1,4-glucan) | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

The reducing sugars liberated from polysaccharide substrate by the enzyme were measured.

Activity is expressed in % of that toward laminarin.

Fig. 1.

Breakdown of β-1,3:1,4-glucan by the Trichoderma endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase.

Notes: A–D, β-1,3:1,4-Glucan, E70-S, and the β-glucans with high, medium, and low viscosity were digested with the Trichoderma endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase, respectively. E and F, E70-S was treated with barley rGI and rGII, respectively. As the products were monitored by refractive index, smaller products eluted with salts at Vi could not be detected.

Isolation of oligosaccharides derived from the minor structure

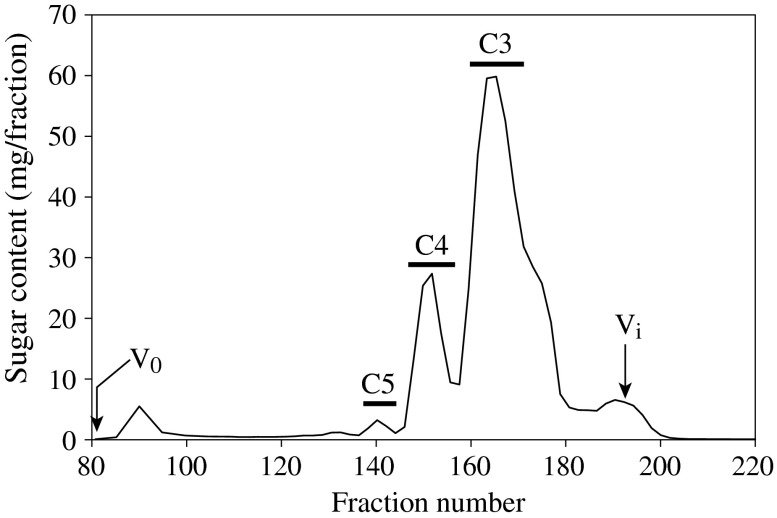

To identify the minor structure of β-1,3:1,4-glucan that is hydrolyzed by the Trichoderma endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase, β-glucan E70-S was first hydrolyzed by GH12 endo-β-1,4-glucanase from A. niger in large scale, and the resulting oligosaccharides were fractionated into C3, C4, and C5 fractions by gel permeation chromatography (Fig. 2). The majority of oligosaccharides were fractionated into C3 and C4 fractions, which are presumably β-Glc-1,4-β-Glc-1,3-Glc (G4G3G) or β-Glc-1,3-β-Glc-1,4-Glc (G3G4G) derived from the cellotriosyl unit and β-Glc-1,4-β-Glc-1,4-β-Glc-1,3-Glc (G4G4G3G), β-Glc-1,4-β-Glc-1,3-β-Glc-1,4-Glc (G4G3G4G), or β-Glc-1,3-β-Glc-1,4-β-Glc-1,4-Glc (G3G4G4G) derived from the cellotetraosyl unit, respectively. The digestion also yielded a small amount (1.5% of total sugar) of C5 fraction presumably derived from the minor structures, on which the endo-β-1,4-glucanase does not act. MALDI-TOF-MS analysis revealed that C5 fraction has an oligosaccharide with DP 5 (Supplemental Fig. 3). The C5 fraction was further separated by paper chromatography into C5-a, -b, and -c (Supplemental Fig. 2). As C5-a and -c consisted of more than one oligosaccharides, C5-b was used for following analysis.

Fig. 2.

Separation of oligosaccharides released from β-1,3:1,4-glucan by endo-β-1,4-glucanase.

Notes: Barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan, E70-S, was hydrolyzed into oligosaccharides with endo-β-1,4-glucanase, and then subjected to gel permeation chromatography on a Bio-Gel P-2 column. V0 and Vt indicate void volume and total inner volume of the column, respectively. The horizontal bars indicate fractions pooled as C3, C4, and C5.

Hydrolysis of C5-b oligosaccharides by Trichoderma endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase

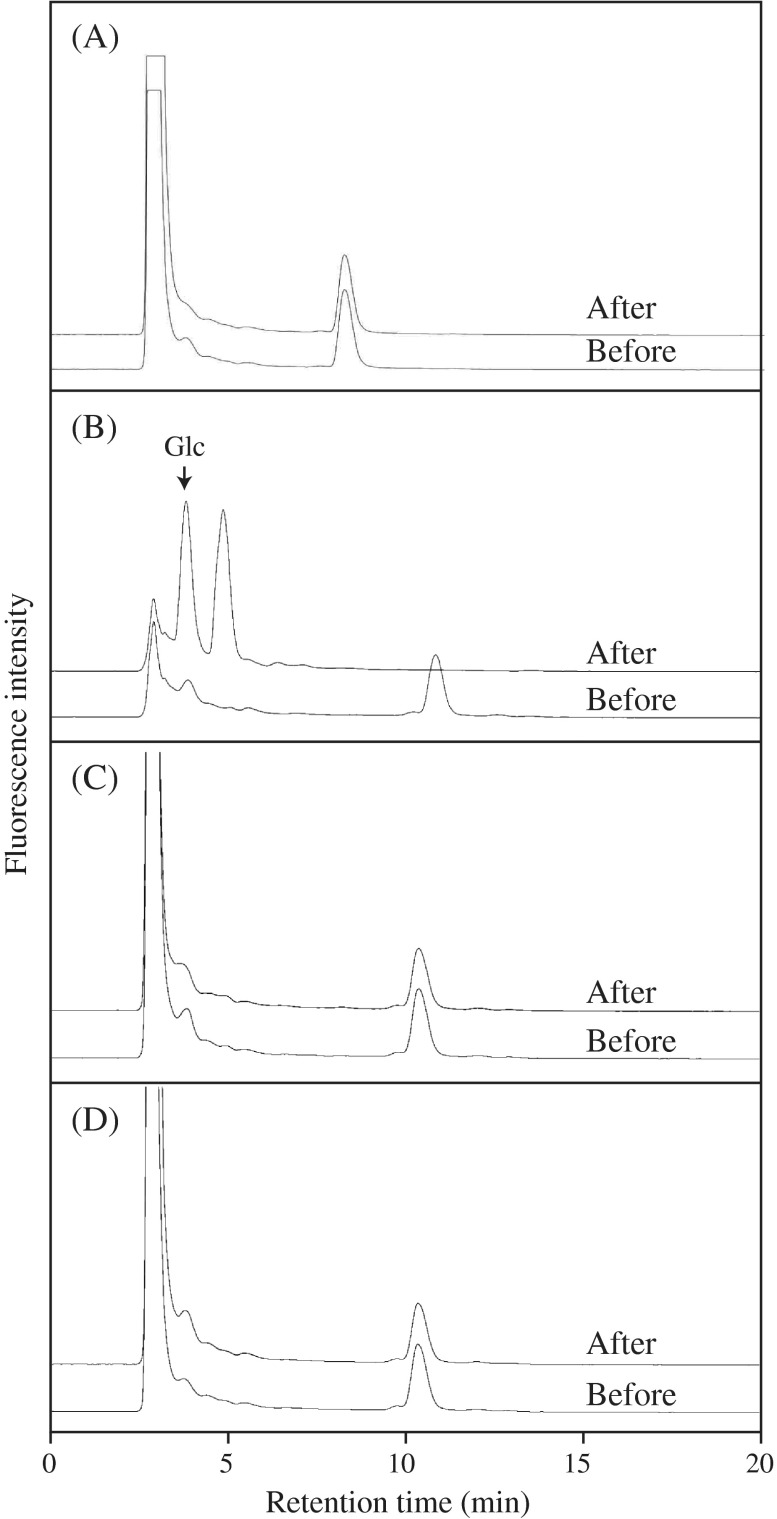

C5-b oligosaccharide was incubated with the Trichoderma enzyme, rGI, or rGII, and the hydrolysis was monitored on HPLC. While rGI and rGII failed to act on the substrate, the Trichoderma enzyme properly degraded C5-b into smaller oligosaccharides and glucose (Glc) (Fig. 3). The results indicate that C5-b structure is hydrolyzed by Trichoderma endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase belonging to GH16, but not by A. niger endo-β-1,4-glucanase belonging to GH12 and barley endo-β-1,3-glucanases belonging to GH17, rGI, and rGII. On the other hand, C4 oligosaccharide derived from cellotetraosyl unit was not hydrolyzed by the Trichoderma enzyme at all.

Fig. 3.

Action of the Trichoderma enzyme, barley rGI and rGII on oligosaccharides prepared from β-1,3:1,4-glucan.

Notes: A, the action of the Trichoderma enzyme on C4; B, the action of the Trichoderma enzyme on C5-b; C, the action of rGI on C5-b; and D, the action of rGII on C5-b were analyzed. Reducing sugars before and after enzyme reaction were derivatized with ABEE and analyzed on HPLC, respectively.

Linkage analysis of oligosaccharides

To determine the structure, C5-b oligosaccharide was subjected to methylation analysis for glucosidic linkages together with C3 and C4 oligosaccharides. In the analysis, sugars at reducing end were converted to their respective alditols before methylation of free OH groups. C4 oligosaccharide appeared to have nearly equal molecular ratio of terminal Glc (t-Glc), 3-linked Glc (3-Glc), 4-linked Glc (4-Glc), and 4-linked reducing-end Glc (4-Glcol), which coincides with the ratio obtained from G3G4G4G (Table 2). Similarly, C3 was identified as G3G4G. Compared with C3 and C4, C5-b had roughly two units of 3-Glc, indicating that C5-b is derived from a cellobiosyl unit or continuous β-1,3-glucosyl residues in β-1,3:1,4-glucan.

Table 2. Glucosidic linkage analysis of oligosaccharides derived from β-glucan, E70-S.

Molar ratio is expressed based on either nonreducing (t-Glc) taken as 1.0.

Samples were methylated after reduction of their reducing ends with NaBH4.

Not detected.

Structure of C5-b oligosaccharide

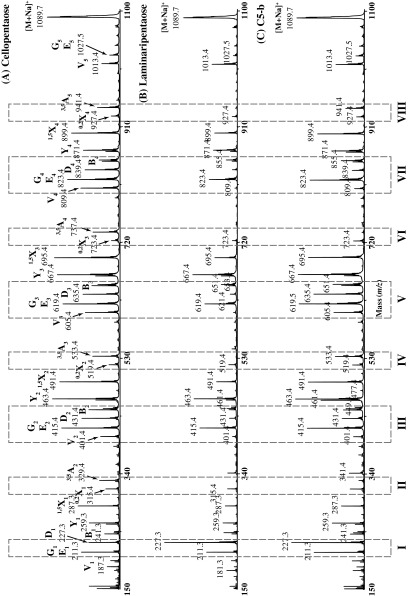

For further structural analysis, C5-b oligosaccharide was also per-methylated and analyzed by high-energy MALDI-CID (Fig. 4, Supplemental Fig. 4). 33 ) However, because the direct annotation of the fragmentation spectrum was very ambiguous, we followed a comparative approach where the CID spectra of per-methylated cellopentaose, laminaripentaose, and C5-b oligosaccharide were simultaneously analyzed. In particular, we compared the relative proportions of various molecular ions in the corresponding spectra in order to decipher the structure of C5-b oligosaccharide. Comparing the CID spectra of cellopentaose and laminaripentaose, it becomes apparent that the intensity of the D1 “elimination ion” (m/z 227.3) 34 ) is higher than the neighboring E1 or G1 “elimination ions” (m/z 211.3) 35,36 ) when the nonreducing-end Glc is 1,3-linked to the second Glc residue (Fig. 4, panel I). In fact, the relative intensity of the D 1 ion in the C5-b CID spectrum is higher than the G 1 or E 1 ion intensity, suggesting that the nonreducing-end Glc is linked via a 1,3-linkage to the second Glc residue. This is further supported by the absence of the 3,5A2 cross-ring fragment ion (m/z 329.4) 33 ) in the C5-b CID spectrum (Fig. 4, panel II) and the absence of the V4 “elimination ion” (m/z 809.4) (Fig. 4, panel VII). A strong 3,5A3 cross-ring fragment ion (m/z 533.4) over a 0,2X2 cross-ring fragment ion (m/z 519.4) 33 ) indicates that the second Glc is 1,4-linked to the middle Glc residue (Fig. 4, panel IV). This is further supported by the presence of a strong V3 “elimination ion” (m/z 605.4) (Fig. 4, panel V). From the comparison of the CID cellopentaose spectrum with the corresponding laminaripentaose spectrum, it becomes apparent that a weak V2 “elimination ion” (m/z 401.4) is indicative of a 1,3-linkage between the middle and penultimate from the reducing-end Glc residues (Fig. 4, panel III). Since the C5-b pre-methylated spectrum has a weak V2 ion, we conclude that in this oligosaccharide the middle Glc residue is 1,3-linked to the penultimate Glc residue. This is further supported by the absence of the 3,5A4 cross-ring fragment ion (m/z 737.4) (Fig. 4, panel VI) and the absence of the D4 “elimination ion” (m/z 839.4) (Fig. 4, panel VII). In Fig. 4, panel VIII, it is shown that a strong 3,5A5 cross-ring fragment ion (m/z 941.4) is indicative of a 1,4-linkage between the penultimate and the reducing-end Glc residues. Taken together, these data allow the C5-b oligosaccharide to be identified as β-Glcp-1,3-β-Glcp-1,4-β-Glcp-1,3-β-Glcp-1,4-Glcp (G3G4G3G4G).

Fig. 4.

Structural characterization of C5-b oligosaccharide by MALDI-CID. Cellopentaose (A), laminaripentaise (B), and C5-b oligosaccharide (C) were per-methylated and analyzed by MALDI-CID.

Notes: The signals used for characterization were boxed numbered from I to VIII. Glucosidic and cross-ring fragments are identified according to the nomenclature of Domon and Costello. 33 )

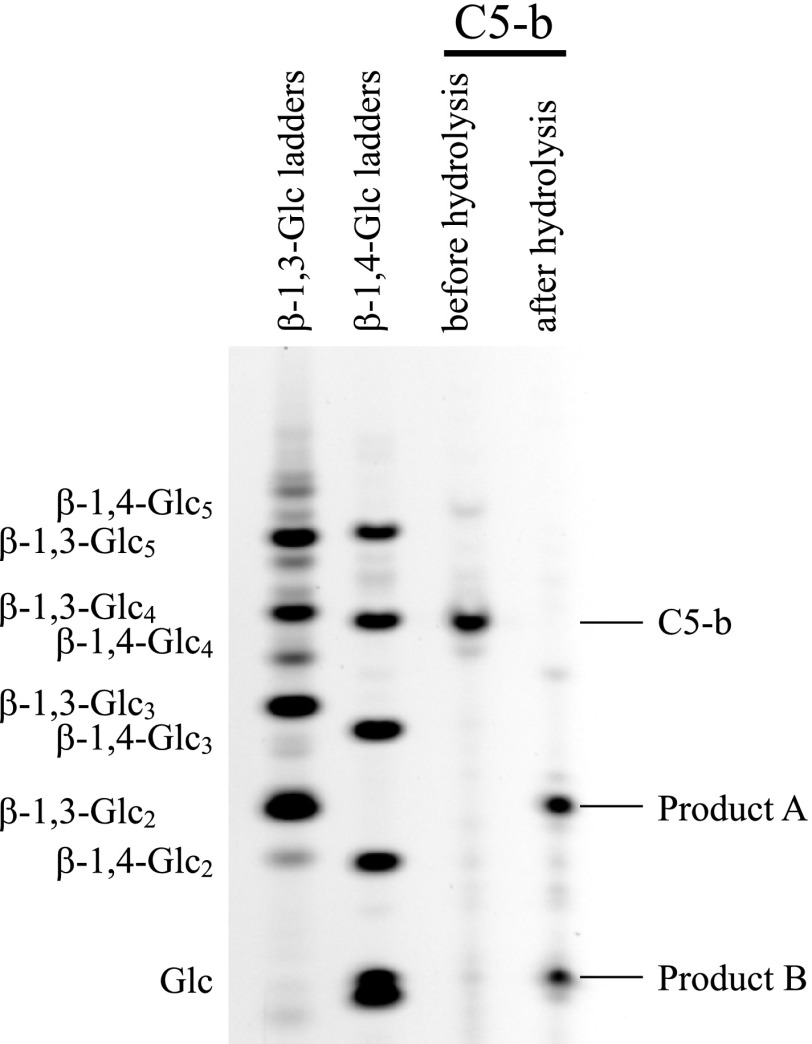

Products released from C5-b by Trichoderma enzyme

As shown in Fig. 3, Trichoderma enzyme properly hydrolyzed C5-b into smaller saccharides; however, the oligosaccharide could not be identified on HPLC. Therefore, the products released from C5-b were also subjected to PACE. As shown in Fig. 5, the smaller saccharides in the products were identified as laminaribiose and Glc. The result suggests that the enzyme acted on both β-1,4-linkages in G3G4G3G4G.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of products released from C5-b oligosaccharides by the Trichoderma enzyme on PACE.

Notes: Products released from C5-b by the Trichoderma enzyme were reductively aminated with 2-aminonaphthaline trisulfonic acid and separated by electrophoresis on acrylamide gels. A series of commercial laminarioligosaccharide (β-1,3-Glc2–5 and Glc) and that of cellooligosaccharide (β-1,4-Glc2–5 and Glc) were used in β-1,3-Glc ladder and β-1,4-Glc ladder markers, respectively. Product A corresponding to laminaribiose and B to Glc are indicated.

Discussion

Poaceae β-1,3:1,4-glucan is mainly consisted of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units linked through single β-1,3-glucosidic linkages, but it has also been shown to possess cellobiosyl units as the minor structure. 4 ) Through the structural analysis of unexpected oligosaccharides released by endo-β-1,3:1,4-glucanase, the cellobiosyl units appeared to locate at the nonreducing side of cellotriosyl units in barley, lichen, and horsetail. 5 ) Based on the proportion of the released oligosaccharides, the frequency of cellobiosyl unit was estimated less than 2% in barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan. 5 ) In this study, based on sugar content, C5 fraction obtained by digestion with A. niger endo-β-1,4-glucanase belonging to GH12 was less than 1.5% of total sugar released from barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan, confirming that the cellobiosyl units exist as the minor structure in barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan.

Together with cellobiosyl unit and long stretch of β-1,4-glucosidic linkage, continuous β-1,3-glucosidic linkages have also been presumed in maize β-1,3:1,4-glucan. 4 ) However, we could not detect any hydrolysis of barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan by barley endo-β-1,3-glucanases belonging to GH17, rGI, and rGII. The fact that laminaritriose is the smallest substrate for GII 22,37 ) suggests that barley β-glucan does not have three continuous β-1,3-glucosyl residues. Hence, the hydrolysis of β-1,3:1,4-glucan by endogenous GI and GII does not likely occur in barley. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that barley β-1,3:1,4-glucan has two continuous β-1,3-glucosyl residues that can be hydrolyzed by distinct endo-β-1,3-glucanases secreted by fungi and bacteria.

In the analysis of 3-D structure of PcLam16A, 20,21 ) two Trp residues have been shown to be involved in the specific recognition of β-1,3-glucosidic linkage between the subsites −1 and −2. In the enzyme, the substrate-binding cleft has a narrow and straight canyon structure along which a linear oligosaccharide such as G4G3G can lay. The Trichoderma enzyme hydrolyzed C5-b oligosaccharide, G3G4G3G4G, into laminaribiose and Glc as the final products. This result suggests that the Trichoderma enzyme either first hydrolyzed G3G4G3G4G into G3G4G3G and Glc, and then into two laminaribioses and Glc, or the enzyme first hydrolyzed G3G4G3G4G into G3G4G and laminaribiose, and then into two laminaribioses and Glc. Because the Trichoderma enzyme did not act on C4 oligosaccharide (G3G4G4G), the former case is more probable. These facts also suggest that the smallest substrate for the Trichoderma enzyme is G3G4G3G.

As well as endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase, GH16 family comprises many carbohydrate active enzymes such as endo-β-1,3-glucanase, endo-β-1,3:1,4-glucanase, β-agarase (EC 3.2.1.81), 38 ) endo-β-1,3-galactanase (EC 3.2.1.181), 39 ) xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase/hydrolase, 40,41 ) and porphyranase (no EC entry). 42 ) On the basis of phylogenetic relationships, it has been proposed that an ancestral enzyme had endo-β-1,3(4)-glucanase (laminarinase) activity. 43,44 ) PcLam16A utilizes partially different subsites for β-1,3:1,4-glucan and β-1,3:1,6-glucan. Although the precise substrate specificity of the ancestral enzyme cannot been known, it is conceivable that the Trichoderma enzyme has adapted to cellobiosyl units as well as cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units in β-1,3:1,4-glucan keeping high activity toward β-1,3:1,6-glucan. The further study on 3-D structure of the Trichoderma enzyme would give an insight into the adaptation mechanism.

Author contribution

Takao Kuge, Kazufumi Tsubaki, Paul Dupree, Yoichi Tsumuraya, and Toshihisa Kotake conceived and designed the experiments. Takao Kuge, Hiroki Nagoya, Theodora Tryfona, Tsunemi Kurokawa, Yoshihisa Yoshimi, and Naoshi Dohmae performed the experiments. Hiroki Nagoya, Yoshihisa Yoshimi, Naoshi Dohmae, Theodora Tryfona, and Toshihisa Kotake analyzed data. Takao Kuge and Kazufumi Tsubaki contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. Theodora Tryfona, Paul Dupree, Yoichi Tsumuraya, and Toshihisa Kotake wrote the paper.

Supplemental material

The supplemental material for this study is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09168451.2015.1046365.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research to T. Kotake [Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research no. 25514001] from Japan Society of the Promotion of Science; Y. Tsumuraya and T. Kotake [Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research no. 24114006] from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. Supports were also provided by BBSRC Sustainable Bioenergy Centre: Cell wall sugars program to P. Dupree [grant number BB/G016240/1].

Supplementary Material

References

- Fincher GB. Molecular and cellular biology associated with endosperm mobilization in germinating cereal grains. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989;40:305–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.001513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X, Fry SC. Evolution of mixed-linkage (1 → 3, 1 → 4)-β-D-glucan (MLG) and xyloglucan in Equisetum (horsetails) and other monilophytes. Ann. Bot. 2012;109:873–886. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC, Nesselrode BH, Miller JG, Mewburn BR. Mixed-linkage (1→3,1→4)-β-D-glucan is a major hemicellulose of Equisetum (horsetail) cell walls. New Phytol. 2008;179:104–115. doi: 10.1111/nph.2008.179.issue-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Nevins DJ. Enzymic dissociation of Zea shoot cell wall polysaccharides: II. Dissociation of (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan by purified (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan 4-glucanohydrolase from Bacillus subtilis . Plant Physiol. 1984;75:745–752. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.3.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons TJ, Uhrín D, Gregson T, Murray L, Sadler IH, Fry SC. An unexpectedly lichenase-stable hexasaccharide from cereal, horsetail and lichen mixed-linkage β-glucans (MLGs): implications for MLG subunit distribution. Phytochemistry. 2013;95:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut DM, Carpita NC. Synthesis of (1 → 3), (1 → 4)-β-D-glucan in the Golgi apparatus of maize coleoptiles. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1993;90:3850–3854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M, Vincent C, Reid JS. Biosynthesis of (1,3)(1,4)-β-glucan and (1,3)-β-glucan in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Properties of the membrane-bound glucan synthases. Planta. 1995;195:331–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00202589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimpara T, Aohara T, Soga K, Wakabayashi K, Hoson T, Tsumuraya Y, Kotake T. β-1,3:1,4-Glucan synthase activity in rice seedlings under water. Ann. Bot. 2008;102:221–226. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RA, Wilson SM, Hrmova M, Harvey AJ, Shirley NJ, Medhurst A, Stone BA, Newbigin EJ, Bacic A, Fincher GB. Cellulose synthase-like CslF genes mediate the synthesis of cell wall (1,3;1,4)-β-D-glucans. Science. 2001;311:1940–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1122975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doblin MS, Pettolino FA, Wilson SM, Campbell R, Burton RA, Fincher GB, Newbigin E, Bacic A. A barley cellulose synthase-like CSLH gene mediates (1,3;1,4)-β-D-glucan synthesis in transgenic Arabidopsis . Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:5996–6001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902019106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanowicz BR, Rayon C, Carpita NC. Topology of the maize mixed linkage (1 → 3),(1 → 4)-β-D-glucan synthase at the Golgi membrane. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:758–768. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC. Update on mechanisms of plant cell wall biosynthesis: how plants make cellulose and other (1 → 4)-β-D-glycans. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:171–184. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.163360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber DJ, Nevins DJ. β-D-glucan hydrolase activity in Zea coleoptile cell walls. Plant Physiol. 1980;65:768–773. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.5.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrmova M, Banik M, Harvey AJ, Garrett TP, Varghese JN, Høj PB, Fincher GB. Polysaccharide hydrolases in germinated barley and their role in the depolymerization of plant and fungal cell walls. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1997;21:67–72. doi: 10.1016/S0141-8130(97)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincher GB, Lock PA, Morgan MM, Lingelbach K, Wettenhall RE, Mercer JF, Brandt A, Thomsen KK. Primary structure of the (1 → 3,1 → 4)-β-D-glucan 4-glucohydrolase from barley aleurone. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1986;83:2081–2085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.7.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Komae K. A rice family 9 glycoside hydrolase isozyme with broad substrate specificity for hemicelluloses in type II cell walls. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:1541–1554. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan M, Burton RA, Dhugga KS, Rafalski AJ, Tingey SV, Shirley NJ, Fincher GB. Endo-(1,4)-β-glucanase gene families in the grasses: temporal and spatial co-transcription of orthologous genes1. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:235-1–235-19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrmova M, Harvey AJ, Wang J, Shirley NJ, Jones GP, Stone BA, Fincher GB. Barley β-D-glucan exohydrolases with β-D-glucosidase activity. Purification, characterization, and determination of primary structure from a cDNA clone. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5277–5286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake T, Nakagawa N, Takeda K, Sakurai N. Auxin-induced elongation growth and expressions of cell wall-bound exo- and endo-beta-glucanases in barley coleoptiles. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:1272–1278. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcd056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai R, Igarashi K, Yoshida M, Kitaoka M, Samejima M. Hydrolysis of β-1,3/1,6-glucan by glycoside hydrolase family 16 endo-1,3(4)-β-glucanase from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium . Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;71:898–906. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasur J, Kawai R, Andersson E, Igarashi K, Sandgren M, Samejima M, Ståhlberg J. X-ray crystal structures of Phanerochaete chrysosporium Laminarinase 16A in complex with products from lichenin and laminarin hydrolysis. FEBS J. 2009;276:3858–3869. doi: 10.1111/ejb.2009.276.issue-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrmova M, Fincher GB. Purification and properties of three (1 → 3)-β-D-glucanase isoenzymes from young leaves of barley (Hordeum vulgare) Biochem. J. 1993;289:453–461. doi: 10.1042/bj2890453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1944;153:375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi M. Notes on sugar determination. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;195:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956;28:350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakomori S. A rapid premethylation of glycolipid, and polysaccharide catalyzed by methylsulfinyl carbanion in dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Biochem. 1964;55:205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albersheim P, Nevins DJ, English PD, Karr A. A method for the analysis of sugars in plant cell-wall polysaccharides by gas liquid chromatography. Carbohydr. Res. 1967;5:340–345. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)80510-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura F, Imaoka A. Chromatographic separation of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides labeled with an ultravioletabsorbing compound,p-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester. Glycoconjugate J. 1988;5:13–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01048328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciucanu I, Kerek F. A simple and rapid method for the permethylation of carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Res. 1984;131:209–217. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(84)85242-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tryfona T, Liang H-C, Kotake T, Kaneko S, Marsh J, Ichinose H, Lovegrove A, Tsumuraya Y, Shewry PR, Stephens E, Dupree P. Carbohydrate structural analysis of wheat flour arabinogalactan protein. Carbohydr. Res. 2010;345:2648–2656. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubet F, Jackson P, Deery MJ, Dupree P. Polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis: a method to study plant cell wall polysaccharides and polysaccharide hydrolases. Anal. Biochem. 2002;300:53–68. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domon B, Costello CE. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate J. 1988;5:397–409. doi: 10.1007/BF01049915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chai W, Piskarev V, Lawson AM. Negative-ion electrospray mass spectrometry of neutral underivatized oligosaccharides. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:651–657. doi: 10.1021/ac0010126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslen SL, Goubet F, Adam A, Dupree P, Stephens E. Structure elucidation of arabinoxylan isomers by normal phase HPLC-MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS/MS. Carbohydr. Res. 2007;342:724–735. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina E, Sturiale L, Romeo D, Impallomeni G, Garozzo D, Waidelich D, Glueckmann M. New fragmentation mechanisms in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight/time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry of carbohydrates. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:392–398. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrmova M, Garrett TP, Fincher GB. Subsite affinities and disposition of catalytic amino acids in the substrate-binding region of barley 1,3-β-glucanases. Implications in plant–pathogen interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:14556–14563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi E, Hatada Y, Akita M, Ohta Y, Yokoi G, Miyazaki T, Nishikawa A, Tonozuka T. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of a GH16 β-agarase from a deep-sea bacterium, Microbulbifer thermotolerans JAMB-A94. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014;6:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2014.988680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake T, Hirata N, Degi Y, Ishiguro M, Kitazawa K, Takata R, Ichinose H, Kaneko S, Igarashi K, Samejima M, Tsumuraya Y. Endo-β-1,3-galactanase from winter mushroom Flammulina velutipes . J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:27848–27854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.251736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MJ, Eklöf JM, Michel G, Kallas AM, Teeri TT, Czjzek M, Brumer H., III Structural evidence for the evolution of xyloglucanase activity from xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases: biological implications for cell wall metabolism. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1947–1963. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.051391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama R, Uwagaki Y, Sasaki H, Harada T, Hiwatashi Y, Hasebe M, Nishitani K. Biological implications of the occurrence of 32 members of the XTH (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase) family of proteins in the bryophyte Physcomitrella patens . Plant J. 2010;64:645–656. doi: 10.1111/tpj.2010.64.issue-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehemann JH, Correc G, Barbeyron T, Helbert W, Czjzek M, Michel G. Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota. Nature. 2010;464:908–912. doi: 10.1038/nature08937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeyron T, Gerard A, Potin P, Henrissat B, Kloareg B. The kappa-carrageenase of the marine bacterium Cytophaga drobachiensis. Structural and phylogenetic relationships within family-16 glycoside hydrolases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:528–537. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel G, Chantalat L, Duee E, Barbeyron T, Henrissat B, Kloareg B, Dideberg O. The κ-carrageenase of P. carrageenovora features a tunnel-shaped active site. Structure. 2001;9:513–525. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.