Abstract

Aim To evaluate the effects of the vaginal erbium laser (VEL) in the treatment of postmenopausal women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM).

Method GSM was assessed in postmenopausal women before and after VEL (one treatment every 30 days, for 3 months; n = 45); the results were compared with the effects of a standard treatment for GSM (1 g of vaginal gel containing 50 μg of estriol, twice weekly for 3 months; n = 25). GSM was evaluated with subjective (visual analog scale, VAS) and objective (Vaginal Health Index Score, VHIS) measures. In addition, in 19 of these postmenopausal women suffering from stress urinary incontinence (SUI), the degree of incontinence was evaluated with the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) before and after VEL treatments.

Results VEL treatment induced a significant decrease of VAS of both vaginal dryness and dyspareunia (p < 0.01), with a significant (p < 0.01) increase of VHIS. In postmenopausal women suffering from mild to moderate SUI, VEL treatment was associated with a significant (p < 0.01) improvement of ICIQ-SF scores. The effects were rapid and long lasting, up to the 24th week of the observation period. VEL was well tolerated with less than 3% of patients discontinuing treatment due to adverse events.

Conclusion This pilot study demonstrates that VEL induces a significant improvement of GSM, including vaginal dryness, dyspareunia and mild to moderate SUI. Further studies are needed to explore the role of laser treatments in the management of GSM.

Key words: ERBIUM LASER, MENOPAUSE, GENITOURINARY SYNDROME OF MENOPAUSE, VAGINAL ATROPHY, DYSPAREUNIA, STRESS URINARY INCONTINENCE

INTRODUCTION

The genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is the new definition for the variety of menopausal symptoms associated with physical changes of the vulva, vagina, and lower urinary tract, related with estrogen deficiency1. GSM is chronic and is likely to worsen over time, affecting up to 50% of postmenopausal women2–8. The symptoms related to GSM include genital symptoms of dryness, burning, irritation, but also sexual symptoms of lack of lubrication, discomfort or pain, and impaired function, as well as urinary symptoms of urgency, dysuria and recurrent urinary tract infections1. All these symptoms may interfere with sexual function and quality of life9–11. Most moisturizers and lubricants are available without prescription, at a non-negligible cost, and may provide only a temporary relief. Conversely, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can provide quick and long-term relief12–15, while urinary symptoms often require additional, effective therapies16–19. When HRT is considered solely for the treatment of vaginal atrophy, local vaginal estrogen administration is the treatment of choice12–15. Although systemic risks have not been identified with local low-potency/low-dose estrogens, long-term efficacy and safety data are lacking. In addition, many women do not accept protracted HRT, or may present absolute contraindications, such as a personal history of estrogen-dependent tumors, particularly endometrial and breast cancer12–15. New management strategies for GSM can increase our armamentarium in order to offer a wide range of options to enable women to choose, considering the benefits and risks associated with each strategy9.

Recently, a seminal paper has clearly demonstrated that a treatment with the microablative carbon dioxide (CO2) laser induced a significant improvement of vaginal health in postmenopausal women20. This paper throws new light on non-hormonal treatment of GSM. Indeed, we have to consider that various lasers possess diverse properties that can be usefully applied in different conditions. The non-ablative erbium laser technology may provide a non-invasive treatment option and it is widely used21–26. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the short-term effectiveness and acceptability of the vaginal erbium laser (VEL) as a new, second-generation, non-ablative photothermal therapy for the treatment of GSM.

METHODS

This is a pilot prospective, longitudinal study performed in postmenopausal women suffering from GSM, attending the outpatient Menopause Clinic of Pisa University Hospital. All women gave written informed consent and an Independent National Advisory Board reviewed this protocol approved by the Division Ethics Committee. Inclusion criteria were the presence of GSM in healthy postmenopausal women (at least 12 months since last menstrual period or bilateral oophorectomy) with plasma gonadotropin and estradiol levels in the postmenopausal range (follicle stimulating hormone > 40 U/l; estradiol < 25 pg/ml) and negative PAP smear. Exclusion criteria were vaginal lesions, scars, active or recent (30 days) of the genitourinary tract infections; abnormal uterine bleeding; use of lubricants or any other local preparations, within the 30 days prior to the study; history of photosensitivity disorder or use of photosensitizing drugs; genital prolapse (grade II–III according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification, POP-Q, system classification); serious or chronic condition that could interfere with study compliance; treatment with hormones or other medicines to relieve menopausal symptoms in the 12 months before the study.

All the participants (n = 45) were treated with the vaginal erbium laser (VEL), a non-ablative, solid-state erbium in yttrium aluminum-garnet crystal (Er:YAG) laser (Fotona Smooth™ XS, Fotona, Ljubljana, Slovenia) with a wavelength of 2940 nm. The spot size (diameter of the laser beam on the target) is 7 mm, with a pulse according to the technique SMOOTH™, at a frequency of 1.6 Hz, and a fluence (laser energy delivered per unit area) of 6.0 J/cm2. The absorbing chromophore of erbium is water. The parameters were selected based on extensive preclinical and clinical studies performed in different experimental conditions25. Briefly, variable square pulse (VSP) technology controls the energy and time duration (or pulse width) simultaneously, reducing the power and increasing the pulse duration. The SMOOTH™ mode, with the sequence of low-fluence longer-shaped erbium pulses, distributes the heat approximately 100 microns deep into the mucosa surface, achieving a controlled deep thermal effect, without ablation. The thickness of mucosa varies, and normally its height is several hundred microns. Therefore, the erbium SMOOTH™ mode pulses allow controlled tissue heating, in a safe and harmless ambulatory procedure without ablation and carbonization of the tissues, practically avoiding the risk of perforation with accidental lesions of the urethra, bladder or rectum. The VEL procedures were performed in an outpatient clinical setting, without any specific preparation, anesthesia, or post-treatment medications. Before the procedures, the vagina was cleaned with disinfectant solution and dried with a swab. Patients were treated with three laser applications (L1, L2, L3) every 30 days, with a screening visit 2–4 weeks prior to the first laser treatment (baseline) and follow-up visits after 4 (T + 4), 12 (T + 12) and 24 (T + 24) weeks from the last laser application.

Briefly, the laser parameters (Renovalase™ Phase 1) were settled with a fluence of 5.5 J/cm2, with the SMOOTH mode at 1.6 Hz; the spot size was 7 mm non-fractional. After inserting a specifically designed vaginal speculum, the probe is inserted into the speculum, with no direct contact with the vaginal mucosa. Thus, circular irradiation of the vaginal wall is performed, with four pulses given every 5 mm, retracting the probe by 5 mm each time (using the graduated scale on the probe). The procedure is repeated until the entrance of the vaginal canal. This procedure is repeated three times, rotating the speculum by 45° each time. Finally, after removing the speculum and using a different probe (PS03 handpiece), the vestibule and introit are irradiated with a spot size of 7 mm, fluence of 10 J/cm2, with the SMOOTH mode at 1.6 Hz (Renovalase™ Phase 2). After treatment, patients are recommended to avoid sexual intercourse for 1 week.

In addition, in 19 postmenopausal women suffering also from stress urinary incontinence (SUI), the degree of incontinence was assessed with the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF), where a maximum score of 21 represents permanent incontinence. None of these patients presented a pelvic organ prolapse greater than stage II, according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system classification. These patients during the VEL procedures were submitted also to additional laser treatment of the anterior vaginal wall (Incontilase™ Phase 1 procedure) specifically designed for urinary incontinence.

As the active control group, we selected a group of 25 postmenopausal women treated with an established treatment for GSM (1 g of vaginal gel containing 50 μg of estriol twice weekly, for 3 months). This formulation provides an ultra-low dose of estriol per application, shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy27.

At the first visit, the eligibility of the patient was verified, the written informed consent was obtained, and the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were collected. Subjective symptoms (vaginal dryness and dyspareunia) were evaluated by a visual analog scale (VAS) at every visit (range 0–10 cm, 0 = total absence of the symptom and 10 cm = the worse possible symptom). In addition, at each visit during the gynecologic examination, the Vaginal Health Score Index (VHIS) was measured. The VHIS evaluates the appearance of vaginal mucosa (elasticity, pH, vaginal discharge, mucosal integrity and moisture). Each parameter is graded from 1 to 5. If the total score is ≤ 15, the vagina is considered atrophic28.

The women were asked to evaluate the general acceptability and efficacy of the finalized therapy as excellent, good, acceptable, bad, or unacceptable. Being an exploratory study, the sample size was not based on a statistical rationale. The sample size was planned to be similar to those of published data20. All the results are reported as the mean ± standard error of absolute values. Baseline values were compared by Student's t-test. Two-way analysis of variance for repeated measures and factorial analysis of variance were used to test the differences within and between the groups, respectively. The post-hoc comparison was made by the Scheffe F-test, using Sigma Stat View software (SPSS Science, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in age, age at menopause and years since menopause, body mass index and basal hormone levels in the two treatment groups before the study (Table 1). In the VEL group, 43 patients completed the study; one patient left the study for personal reasons and one left because of the discomfort related to the first application. In the estriol group, 19 women completed the study, while the others dropped out because of personal problems or because they needed other pharmacological or surgical interventions.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants who completed the study. The women either received treatment with the vaginal erbium laser (VEL) or vaginal estriol gel supplementation (see text for details). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

|

VEL group (n = 43) |

Estriol group (n = 19) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.9 ± 8.1 | 63 ± 4.5 |

| Age at menopause (years) | 49.3 ± 4.1 | 51.7 ± 3.3 |

| Years since menopause | 12.5 ± 5.8 | 11.8 ± 3.1 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 3.3 | 25 ± 3.0 |

| FSH (IU/l) | 85.4 ± 7.8 | 81.5 ± 4.5 |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 18.4 ± 2.3 | 20.2 ± 3.4 |

FSH, follicle stimulating hormone

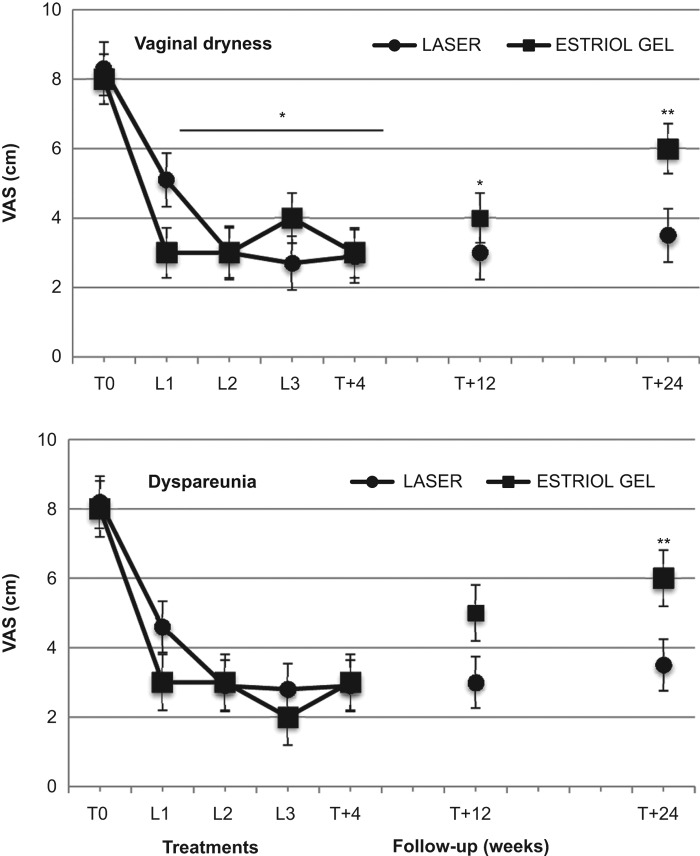

The basal VAS and VHIS scores were similar in the two groups (Figures 1 and 2). In both groups, the VAS scores for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, from basal values (T0) of 8.3 ± 1.3, and 8.2 ± 1.3 cm, respectively, showed significant (p < 0.01) decreases to 5.1 ± 1.4 and 4.5 ± 1.6 cm, respectively, 4 weeks after the first VEL treatment or 4 weeks of estriol cream (L1), to 3.0 ± 1.1 and 2.8 ± 1.5 cm, respectively, after the second VEL treatment or 8 weeks of estriol cream (L2), to 2.7 ± 0.7 and 2.8 ± 1 cm, respectively, after the third VEL treatment or 12 weeks of estriol cream (L3) (Figure 1). In the follow-up period, the dryness and dyspareunia values were 2.9 ± 0.6 and 2.8 ± 1.0 cm, respectively, 4 weeks after the last VEL or last estriol cream application (T + 4), 3.0 ± 0.6 and 3.1 ± 0.9 cm, respectively, after 12 weeks (T + 12), and 3.5 ± 0.9 and 3.5 ± 1.1 cm, respectively, 24 weeks after the last VEL or last estriol cream application (T + 24). The difference from baseline values was statistically significant (p < 0.01) after the first laser treatment and the values remained significantly lower after the second and third laser applications, as well as during the follow-up period up to the 24 weeks of observation (Figure 1). The VAS values in the estriol group showed a similar decrease during the treatment period, with a comparable pattern, and no significant difference was evident between the VEL and estriol groups during the treatment period. Conversely, the VAS scores for both vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in the estriol group showed a small but significant increase after the end of the treatment period (Figure 1). The values measured after 24 weeks (T + 24) in the estriol group were significantly (p < 0.05) different from corresponding values measured in the VEL group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of second-generation laser thermotherapy on vaginal dryness (upper panel) and dyspareunia (lower panel) using the visual analog score (VAS) on a 10-point scale for the women receiving laser treatment (n = 43) and the women receiving estriol (n = 19). See text for details. *, p < 0.01 vs. corresponding basal values in both groups; **, p < 0.05 vs. estriol basal values and corresponding laser group values.

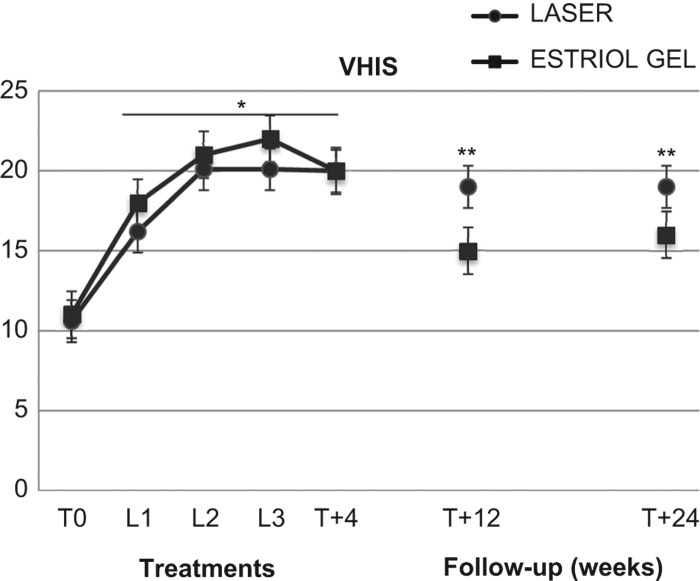

Figure 2. Effect of second-generation laser thermotherapy on the Vaginal Health Score Index (VHIS) for the women receiving laser treatment (n = 43) and the women receiving estriol (n = 19). See text for details. *, p < 0.01 vs. corresponding basal values in both groups; **, p < 0.05 vs. estriol basal values and corresponding laser group values.

The VHIS increased significantly (p < 0.01) in both the VEL and estriol groups, from basal values (T0) of 10.6 ± 3.6 and 11.2 ± 2.8, respectively, to 16.6 ± 2.1 and 18.2 ± 3.2, respectively, after the first VEL treatment (L1); 20.1 ± 1.8 and 21.2 ± 2.9, respectively, at L2; 20.1 ± 1.8 and 22.4 ± 4.0, respectively, at L3; the values were 20.0 ± 1.4 and 20.1 ± 3.1, respectively, after 4 weeks of follow-up (T + 4); 19.8 ± 1.3 and 15.3 ± 1.5, respectively, after 12 weeks of follow-up (T + 12); and 19.0 ± 1.4 and 16.2 ± 1.7, respectively, after 24 weeks of follow-up (T + 24) (Figure 2). The values measured after 12 and 24 weeks (T + 12 and T + 24) in the estriol group were significantly (p < 0.05) different from corresponding values measured in the VEL group (Figure 2).

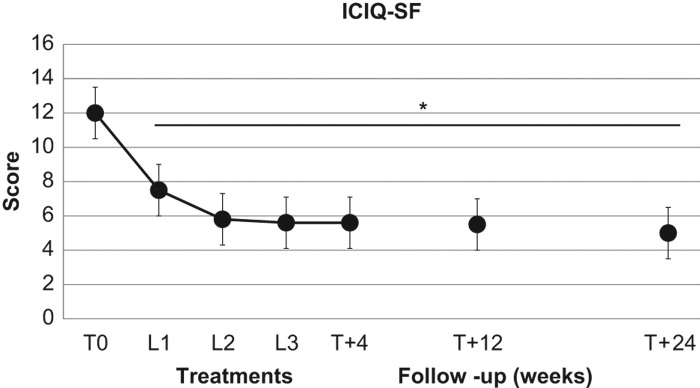

In the 19 patients suffering from SUI, the VEL treatment induced a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in the ICIQ-SF scores from basal values of 12.0 ± 1.8, to 7.5 ± 2.4 at T1, to 5.8 ± 2.6 at T2, and 5.6 ± 2.6 at T3. The ICIQ-SF scores remained significantly (p < 0.01) lower than basal values at T + 4 (5.5 ± 2.6), at T + 12 (5.5 ± 2.9) as well as at T + 24 (5.0 ± 2.6) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of second-generation laser thermotherapy on International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ-SF) score in 19 postmenopausal women suffering from stress urinary incontinence. *, p < 0.01 vs. corresponding basal values. See text for details.

VEL was well tolerated, with less than 3% of patients discontinuing treatment due to adverse events: one patient defined the procedure as unacceptable, reporting a burning sensation starting 36 h after the first application and lasting for a couple of days. One patient left the study for personal reasons. In the 43 valid completers in the VEL group, 34 patients (79.5%) defined the procedure as excellent–good, seven patients (16.3%) as acceptable, and two patients (4.2%) reported their experience as bad. In the estriol group, 16 patients (84%) defined the treatment as excellent–good, while three patients defined the vaginal treatment, respectively, as acceptable, bad or unacceptable.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study designed to evaluate the effects of VEL as second-generation laser thermotherapy on GSM. Our data show that VEL is well tolerated by women who subjectively perceived a clinical benefit that was confirmed by the objective improvement of the vaginal milieu, as measured by the VHIS. These results indicate that VEL treatment is able to induce a rapid and long-lasting improvement in the signs and symptoms of GSM. A significant subjective and objective improvement was evident after the first laser application; a more pronounced effect was apparent after the second and third laser applications, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. No anesthesia was necessary and the effects were long lasting, at least up to the 6-month follow-up after the last VEL application. Our study is a pilot prospective, longitudinal study and has the limitation of sample size. However, the data obtained in the VEL group were compared with those obtained in a group of similar women treated with a standard estrogen treatment for GSM27. Present results show comparable effects of VEL and estriol treatment on GSM parameters. In the estriol group, a reduction of efficacy can be seen 12 weeks after the end of treatment. Conversely, the VEL group maintained the same positive results throughout all the study period up to the 6-month follow-up.

Salvatore and colleagues20, in a recent noteworthy paper, clearly demonstrated that microablative CO2 laser energy is effective in improving vaginal dryness as well as dyspareunia and VHIS, in a 12-week follow-up study. This paper clearly indicates that laser may be considered a new opportunity for non-hormonal treatment of GSM20. The procedure was easy to perform, particularly after the first laser application, and the insertion of the probe into the vaginal canal was well tolerated20. The procedure used in our study is slightly different for that used with the microablative CO2 laser. The VEL procedure is performed using a special vaginal speculum introduced as a guide for the handpiece laser beam delivery system. Thus, the patients do not feel the several longitudinal passes performed using a step-by-step retraction of the handpiece. In a two-step protocol, the laser irradiation was applied first into the vaginal canal and after at the introitus area. The innovative techniques used in the VEL procedures can guarantee not only the efficacy, but also, mainly, an intrinsic safety, since the erbium beam cannot damage the tissues in depth, eliminating the risk of tissue necrosis, in a non-ablative form, without abrasion or bleeding21–25. This characteristic makes the erbium laser an ideal candidate for the thermal treatment of the vaginal walls21–25. The SMOOTH technique releases precise impulses, leading to a controlled rise in tissue temperature for vasodilation and up to the optimum for the collagen remodeling and neocollagenesis, comprised in a range between 45° and 60°C21–25. The collagen exposed to an appropriate temperature is contracted and this leads to the temporary shrinkage, which stimulates a subsequent remodeling, with the consequent generation of new collagen and an overall improvement of the elasticity of the treated tissue. In the treatment of superficial tissues, the laser can be provided in a fractionated manner, producing a matrix of small ‘islands’ on the surface of the tissue25. The fractionated technique is comfortable for the patient, allowing the use of higher fluences in the irradiated points. For the treatment of SUI, the vaginal anterior wall is treated with five passes in addition to the passes irradiating the entire vaginal canal at 360°.

Taken together, these data clearly suggest that laser energy can be used for the treatment of postmenopausal women suffering from GSM. Our study confirms and extends previous data reported with VEL in abstract form by Gaspar and colleagues26. VEL can determine an increase of epithelial thickness and glycogen content, associated with changes in lamina propria, increased angiogenesis, collagenesis, papillomatosis and cellularity of the extracellular matrix26. All these changes are long lasting and can be observed 6 months after the last VEL treatment26. These results are confirmed by our findings, showing persistent effects of VEL 24 weeks after the end of treatment. At variance from Gaspar and colleagues26, in our study the VEL treatment was performed in postmenopausal women suffering from GSM without any previous or concomitant treatment with estrogens or even non-hormonal vaginal creams. Therefore, our study suggests that the effects of VEL are independent from any pretreatment, suggesting that VEL can be proposed in postmenopausal women who cannot be treated with hormones, as in breast cancer survivors. The possible difference in the outcomes with or without estrogen pretreatment or the current use of estrogenic or non-hormonal therapies is a matter of future studies. In addition, our data suggest that VEL treatments can be of help in postmenopausal women suffering from mild to moderate SUI. In fact, in postmenopausal women suffering from GSM and also mild to moderate SUI, the VEL improved the ICIQ-SF scores. The effect of VEL on SUI is of particular interest. Urinary incontinence is a common and important health-care problem that is underreported, underdiagnosed, and therefore undertreated in women. The non-surgical treatment of SUI29 is a major challenge for women's health. Non-pharmacologic management for SUI, such as pelvic floor muscle training, is effective, can improve SUI and may provide complete continence, but many patients discontinue the treatment. As previously reported by Fistonic and colleagues30–32, our preliminary data indicate that VEL might be useful for the non-invasive treatment of SUI. Obviously, future well-designed and controlled studies are needed to validate the use of VEL for SUI. In our study, we did not explore with appropriate tests the effects of VEL on sexuality. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effects of VEL on sexuality in postmenopausal women suffering from GSM.

In conclusion, this pilot study suggests that the treatment with VEL is reasonable, efficacious and safe as a new, second-generation, non-ablative photothermal therapy for the treatment of GSM. Further larger, long-term and well-controlled studies are required to explore the use of VEL in comparison with different therapeutic options, in order to offer a procedure as an alternative or in association with proven therapies, as a new safe and effective option to treat GSM symptoms in menopausal practice.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest During the past 2 years, Dr Gambacciani has had financial relationships (lecturer, member of advisory boards and/or consultant) with Bayer Pharma, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Italfarmaco, Teva/Theramex. Dr Levancini and Professor Cervigni report no conflict of interest.

Source of funding Nil.

References

- Portman DJ, Gass MLS. on behalf of the Vulvovaginal Atrophy Conference Panel Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and The North American Menopause Society. Climacteric. 2014;17:557–63. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.946279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2010;13:509–22. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.522875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society Menopause. 2013;20:888–902. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a122c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Toozs-Hobson P, Cardozo L. The effect of hormones on the lower urinary tract. Menopause Int. 2013;19:155–62. doi: 10.1177/1754045313511398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Cardozo L. The pathophysiology and management of postmenopausal urogenital oestrogen deficiency. J Br Menopause Soc. 2001;7:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger B, Hait H, Reape KZ, Shu H. Measuring symptom relief in studies of vaginal and vulvar atrophy: the most bothersome symptom approach. Menopause. 2008;15:885–9. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318182f84b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:437–47. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S44579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oge T, Hassa H, Aydin Y, Yalcin OT, Colak E. The relationship between urogenital symptoms and climacteric complaints. Climacteric. 2013;16:646–52. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.756467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suckling JA, Kennedy R, Lethaby A, Roberts H. Local estrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;((4)):1–104. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2133–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:87–94. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. Executive summary: Postmenopausal hormone therapy: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95((Suppl 1)):s1–66. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society Menopause. 2012;19:257–71. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824b970a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers TJ, Gass MLS, Haines CJ, et al. Global Consensus Statement on Menopausal Hormone Therapy. Climacteric. 2013;16:203–4. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2013.771520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers TJ, Pines A, Panay N, et al. on behalf of the International Menopause Society Updated 2013 International Menopause Society recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health. Climacteric. 2013;16:316–37. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2013.795683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarenis I, Cardozo L. Managing urinary incontinence: what works? Climacteric. 2014;17((Suppl 2)):26–33. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.947256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody JD, Jacobs ML, Richardson K, Moehrer B, Hextall A. Oestrogen therapy for urinary incontinence in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:D001405. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001405.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelken RS, Ozel BZ, Leegant AR, Felix JC, Mishell DR. Randomized trial of estradiol vaginal ring versus oral oxybutynin for the treatment of overactive bladder. Menopause. 2011;18:962–6. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182104977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng LH, Wang AC, Chang YL, Soong YK, Lloyd LK, Ko YJ. Randomized comparison of tolterodine with vaginal estrogen cream versus tolterodine alone for the treatment of postmenopausal women with overactive bladder syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:47–51. doi: 10.1002/nau.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Zerbinati N, et al. A 12-week treatment with fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. Climacteric. 2014;17:363–9. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.899347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann R, Hibst R. Pulsed Erbium: YAG laser ablation in cutaneous surgery. Lasers Surg Med. 1996;19:324–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1996)19:3<324::AID-LSM7>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds N, Cawrse N, Burge T, Kenealy J. Debridement of a mixed partial and full thickness burn with an erbium: YAG laser. Burns. 2003;29:183–8. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi CE, Puricelli E, Kulkes S, Martins GL. Er: YAG laser in oral soft tissue surgery. J Oral Laser Applications. 2001;1:24. [Google Scholar]

- Levy JL, Trelles MA. New operative technique for treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum: laser inverted resurfacing: preliminary report. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50:339–43. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000044249.10349.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizintin Z, Rivera M, Fistonic I, et al. Novel minimally invasive VSP Er: YAG laser treatments in gynecology. J Laser Health Acad. 2012;1:46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar A. Comparison of new minimally invasive Er: YAG laser treatment and hormonal replacement therapy in the treatment of vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2014;17((Suppl 1)):124. [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Estevez J, Usandizaga R, et al. The therapeutic effect of a new ultra low concentration estriol gel formulation (0.005% estriol vaginal gel) on symptoms and signs of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: results from a pivotal phase III study. Menopause. 2012;19:1130–9. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182518e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann GA, Notelovitz M, Kelly SJ, et al. Long-term non-hormonal treatment of vaginal dryness. Clin Pract Sexuality. 1992;8:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, et al. Nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence in women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:429–40. doi: 10.7326/M13-2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fistonic I. Laser treatment of early stages of stress urinary incontinence significantly improves sexual life. Presented at Annual Conference of European Society for Sexual Medicine; December 2012; Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Fistonic I. Erbium laser treatment for early stages of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in women. Presented at Annual Meeting of International Urogynecological Association; May 2013; Dublin. [Google Scholar]

- Fistonic I. Erbium laser treatment for early stages of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and vaginal relaxation significantly improves pelvic floor function. Presented at 15th Congress of Human Reproduction; March 2013; Venice. [Google Scholar]