Abstract

Dissociation of gaseous protein complexes produced by native electrospray often induces an asymmetric partitioning of charge between ejected subunits. We present a simple asymmetric charge partitioning factor (ACPF) to quantify the magnitude of asymmetry in this effect. When applied to monomer ejection from the cytochrome c dimer and β-amylase tetramer, we found that the ~60-70% of precursor charge ending up in the ejected monomers corresponds to ACPFs of 1.38 and 2.51, respectively. Further, we used site-specific fragmentation from electron transfer dissociation (ETD) to identify differences in fragmentation and characterize domains of secondary-structure present in the dimer, ejected monomers, and monomers obtained directly from electrospray ionization (ESI). We found evidence of structural changes between the dimer and ejected monomer, but also that the ejected monomer had a nearly identical set of fragment ions produced by ETD as the ESI monomer with the same charge state. Surprisingly, APCF values for ETD fragment ions generated directly from the dimer revealed that the fragments undergo asymmetric charge partitioning at over twice the magnitude of that observed for ejection of the monomer.

Keywords: protein complexes, proteomics, electron transfer dissociation, asymmetric charge partitioning

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Native electrospray ionization (ESI) coupled with mass spectrometry has proven extremely useful for the analysis of large assemblies of biological macromolecules.1,2 Because many non-covalent interactions are maintained during ionization, it is possible to study protein-protein3,4, and protein-ligand5 complexes by mass spectrometry (MS) that would be destroyed under denaturing conditions. The stoichiometry of these macromolecular assemblies plays a critical role in many cellular processes6, including disease states7, making the direct observation of an intact complex of high interest in the study of biological and gas-phase phenomena alike.

Beyond high-accuracy intact mass measurement, gas-phase fragmentation can provide further identification and characterization of the intact complex8,9 as well as individual subunits.10,11 In addition, fragmentation using electron capture dissociation (ECD) can cleave covalent protein backbone bonds while maintaining nearby non-covalent interactions.12 Recent studies have utilized this unique property to provide information about the higher-order structure of gaseous proteins13-15 and protein complexes.8,16 Similarly, native electron capture dissociation (NECD), a new sub-type of radical dissociation that is induced by heating the transfer capillary instead of the addition of exogenous electrons, was used to probe the gas-phase unfolding of the cytochrome c dimer.17,18

On the other hand, threshold dissociation of protein complexes by collisional or photon-based activation often liberates one or more monomers with a disproportionately high charge, in a process first described by Light-Wahl, et al. in 1994.19 The effect has been studied by many labs since, and termed “Asymmetric Charge Partitioning” (ACP).20-22 It can be attributed to, among other reasons, the unfolding of one monomer prior to or during ejection, causing it to acquire far more charge than would be expected based on its portion of the mass of the intact complex.23 Studies by the Robinson group have further showed a close correlation between the ratio of surface areas of the ejected monomer and the intact complex and the overall degree of charge transfer.24 Experimental results from several labs on a variety of systems25 have also reproduced the effect and found ACP to be dissociation method26 and sometimes charge state23 dependent. Theoretical studies have also been performed, using molecular dynamics27 and other modeling methods.28

Here, we introduce a simple metric for quantifying ACP, and use electron transfer dissociation (ETD)29, a radical fragmentation technique similar to ECD, to probe the secondary structures in the gas-phase cytochrome c dimer, its ejected monomer, and the analogous monomer produced via electrospray. We not only find evidence of the structural changes between the dimer and ejected monomer, but also of an ACP upon dissociation of the fragment ions formed by ETD. This observation provides the first characterization of ACP as a general phenomenon for any sub-structural element liberated from a protein complex.

2. Material and Methods

Horse heart cytochrome c was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used without further purification. Cytochrome c samples were sprayed at 5 μL/min from a 0.26 mg/mL solution in 100 mM ammonium acetate on an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany). β-amylase samples were purchased from Sigma Aldrigh (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were buffer exchanged into 100 mM ammonium acetate using 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Samples were sprayed and analyzed with a modified Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) as described previously10.

ETD was performed with fluoranthene as the reagent using an N2 carrier gas. When ETD was performed for precursor charge reduction without fragmentation (ETnoD),30 the reaction time was increased (generally >5 ms) to maximize the signal of the targeted reduced-charge species. When ETD was performed for backbone cleavage, ETD reaction times were set to maximize fragment ion production while minimizing reduced precursor ion signal, generally 2-10 ms depending on the original precursor charge state. CAD indicates RF-induced collisional activation and was performed in an ion trap. CAD was used to produce the ejected monomer as well as to break non-covalent bonds after ETnoD (i.e. supplemental activation) in selected experiments. All data were analyzed manually with the freely available software, mMass.31 Ion yields were normalized by charge to account for the linear detection bias in the Orbitrap analyzer.32

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Monomer Ejection from the Dimer of Cytochrome c

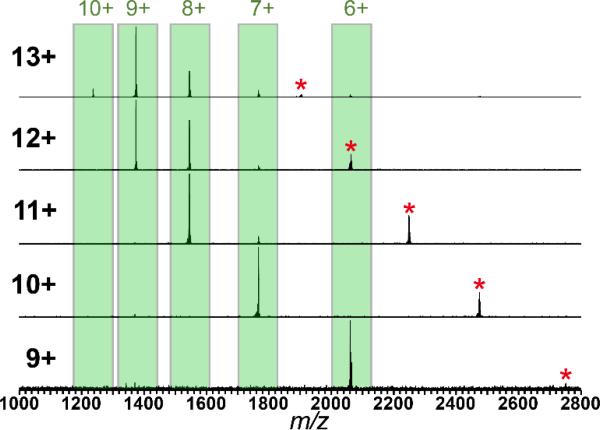

Fig. 1 depicts spectra of cytochrome c monomers ejected from dimeric precursors of selected charge states. In the top panel, the 13+ charge state of horse heart cytochrome c dimer was isolated and activated with CAD to eject monomer ions of charge states 10+ – 6+. To prevent overlap of dimer and monomer signals, the isolated 13+ dimer was subjected to ETD at reaction times optimized for formation of the reduced-charge precursors that have not fragmented (ETnoD).30 Each of the 12+ -9+ reduced-charge dimer species were then isolated individually, and activated with CAD to eject monomers. No significant yields of c- or z-fragment ions were observed relative to signals from monomer ejection. Each dimer charge state is therefore a product of the parent 13+ ion, however, isolation and activation of the ESI-formed 11+ ion produced similarly-charged ejected monomers (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ejected monomer species observed from isolation of the 13+ through 9+ species of the cytochrome c dimer (precursor charge state listed at far left). The 12+ to 9+ parent ions (indicated by an asterisk) were formed by charge reduction (ETnoD) of the 13+ during the ETD process.

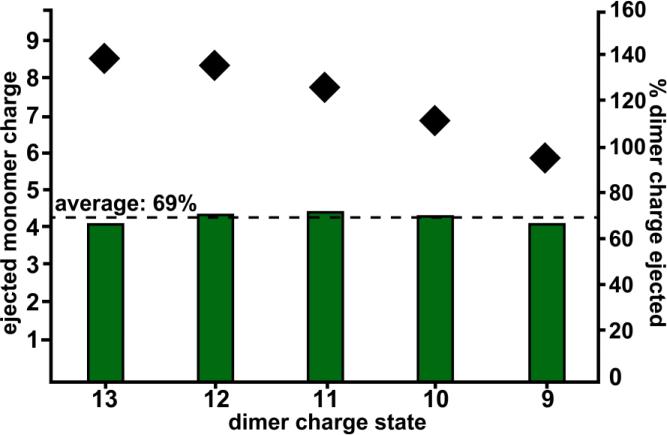

Fig. 2 shows the intensity-weighted average charge of ejected monomers resulting from each dimer charge state (black diamonds). The green bars underneath indicate the percent of the precursor charge represented by the weighted-average monomer charge. Despite the general downward trend of ejected monomer charge (Fig. 2), the overall percent remains remarkably constant, varying from 66-72%. Thus, the magnitude of ACP does not change even with a 31% decrease in precursor charge density, indicating that it is more affected by the relative unfolding of the two subunits than it is by the Coulombic strain of charges on the precursor for the 13-9+.

Figure 2.

Black diamonds indicate the intensity-weighted average charge of the ejected monomers (left axis) observed after isolation and fragmentation of each dimer charge state (x-axis). The green bars represent the percent of charge from the dimeric precursor that is observed in each monomer for each monomer ejection experiment (right axis).

Monomer charge states from all of the ejected dimers show significant evidence of ACP. A previous study by Williams and co-workers23 found significant differences between the monomer ejection from cytochrome c dimers formed directly by ESI when compared to those formed by gas-phase deprotonation of isolated higher charge states. Specifically, they found that when the 15+ cytochrome c dimer is deprotonated to form the 13+, it produces symmetrically-ejected monomers. The current results do not show any evidence of this effect: the doubly-reduced 11+ dimers produced nearly identical ejected monomers when compared to those produced from the ESI-formed 11+. The apparent discrepancy in results can be attributed to several factors, including the higher pressure of the ion trap (~4 mTorr) when compared to that found in an ICR instrument and the difference in proton transfer/electron transfer reagent (diethylamine instead of the fluoranthene used here). The magnitude of ACP can also vary greatly for complexes electrosprayed out of different solution conditions and at different concentrations; a previous study by Smith and co-workers33 showed no ACP with dissociation of cytochrome c dimers under denaturing conditions. Indeed, the full mass spectrum of cytochrome c prior to isolation and dissociation (Supplementary Fig. 2) shows monomer species of relatively high charge (12+ - 10+) indicating some degree of solution denaturation.

3.2 Asymmetric Charge Partitioning Factor

In order to formalize the magnitude of ACP, we introduce the asymmetric charge partitioning factor (ACPF, Eq. 3.2.1), which can be used to compare ACP across multiple systems with different numbers of subunits.

| Eq. 3.2.1 |

Here, CES and CI indicate the intensity-weighted average charges of the ejected subunits and the intact complex, respectively, while MES and MI indicate the masses of the ejected subunit and complex, respectively. Essentially, the ACPF compares the average charge present on observed ejected subunits with the theoretical charge that would be present following a symmetric partitioning of charge from the precursor protein complex. A completely symmetric charge partitioning would be indicated by an ACPF of 1, with higher values indicating increasingly asymmetric charge partitioning. Note that because this factor uses the intensity-weighted average charge of the ejected monomers, m/z-dependent biases in measuring intensity will affect APCF values.

The example of the 13+ cytochrome c dimer mentioned in section 3.1 produces an intensity-weighted average ejected monomer charge of 8.66 (Figs. 1 and 2), corresponding to an ACPF of 1.33. Monomer ejection from the other dimer charge states produced product ions with a similar percent of the total precursor charge, thus their ACPF values are also similar (1.33-1.43).

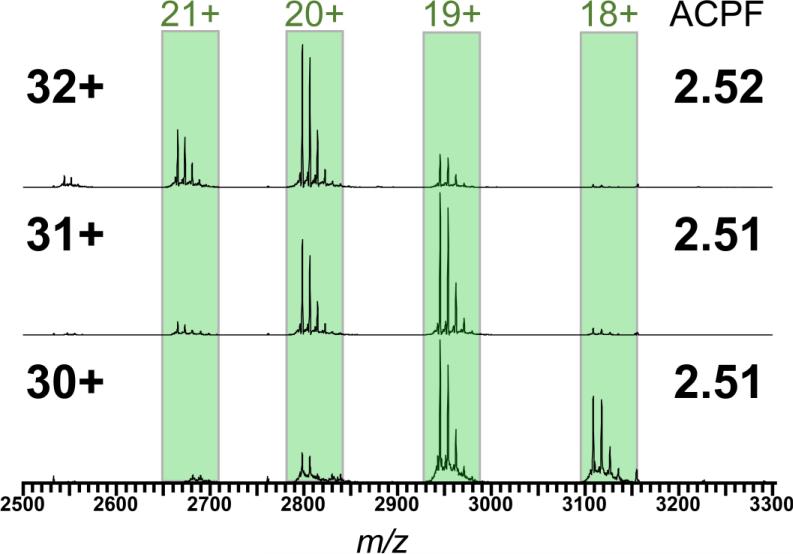

In order to show its application to a variety of systems, we use the ACPF to examine monomer ejection of the 224 kDa homotetrameric β-amylase purified from sweet potatoes. The ejected monomers from the quadrupole-isolated 32+, 31+ and 30+ intact tetramers are shown in Fig. 3. Heterogeneity in the monomer mass can be attributed to differing numbers of hexose subunits (multiples of 162 Da), likely due to differential O-glycosylation. The calculated ACPFs range from 2.51-2.52 (Fig. 3), again appearing to be little affected by the precursor charge. Thus, we can directly compare the magnitude of ACP in β-amylase with that of cytochrome c dimer by using the ACPF, indicating a nearly two-fold stronger charge partitioning effect in the tetramer. Higher ACP has previously been described for monomer ejection from tetramers when compared with that from dimers, and has been attributed to the change in the ratios of surface areas between the two species24.

Figure 3.

Monomers ejected in the gas phase from isolated charge states of the homotetrameric complex β-amylase; charge states of the precursor tetramer are indicated by the numbers at far left, ACPF values are indicated by numbers on far right.

3.3 ETD Fragmentation

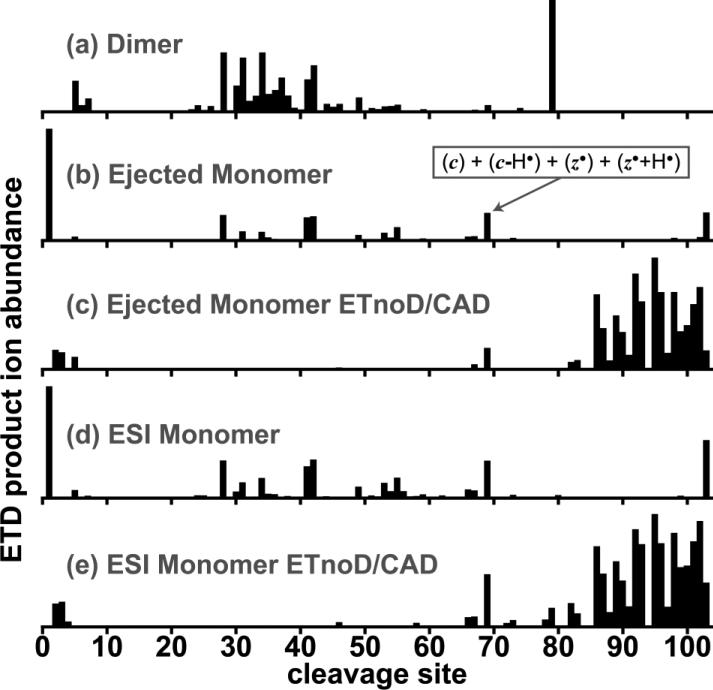

ETD fragment ion yields from the 13+ cytochrome c dimer are plotted with respect to their cleavage sites in Fig. 4a. Here, c and z fragment yields (both even- and odd-electron species were observed from both fragment types) are summed together. All yields are normalized to the base peak intensity. Cleavage products are plotted in the same way for the 9+ ejected monomer in Fig. 4b. On the other hand, Fig. 4c shows electron-based cleavage products for the ejected monomer after ETD, followed by isolation of the singly-reduced (M+9H)8+• ETnoD molecular ion, and further subjected to low-energy CAD to release electron transfer fragment ions that had not completely dissociated. Although low abundance b- and y-fragments were observed, they were not considered as they likely occurred during the CAD process.

Figure 4.

Site-specific ETD product ion abundances (sum of even- and odd-electron c- and z-fragment ions) from each cleavage site observed from the following five precursors and experiments: (a) ETD of the intact 13+ dimer of cytochrome c, (b) ETD of the 9+ ejected monomer, (c) ETnoD of the 9+ ejected monomer with additional activation by gentle CAD to break non-covalent interactions, (d) ETD of the 9+ ion monomer obtained directly from electrospray, and (e) ETnoD of the electrosprayed 9+ ion of the monomer followed by gentle CAD. All fragment ions abundances are normalized to that of the base peak, which is set to 1.

Fragmentation yields from the dimer appear to exhibit similar relative abundances when compared to those from the ejected monomer (e.g. yields from backbone cleavage sites 28, 41, and 42). However, the dimer undergoes increased fragmentation around site 37, and its most abundant peak, from site 79, is not present in the monomer. The presence of additional fragmentation channels in the dimer is consistent with a different set of cytochrome c conformers that are not present in the ejected monomer. Further, the dimer form of cytochrome c does not exist under biological conditions, contributing to increased heterogeneity in the dimer fold. It is possible that the other monomer-monomer contacts in the dimer provide additional stabilization for conformers that are unstable by themselves. Additional fragmentation from the dimer is also remarkably similar to that found after native electron capture dissociation17, which produced the most abundant fragmentation from cleavage site 79 as well.

Neither the dimer nor the ejected monomer produced substantial fragmentation from the C-terminal region, with significant fragment yields only occurring in the ejected monomer after ETnoD and subsequent activation with CAD (Fig. 4c). Similar to previous experiments that followed ECD with activation by infrared photons,13 the additional fragment ions formed from gentle CAD indicate that it is a region with significant higher-order structure where the products from backbone cleavage events are prevented from dissociation by non-covalent interactions. These results are consistent with gas-phase salt bridging in that region, predicted to be one of the strongest non-covalent interactions in the gas phase.34

Product ion yields from the ESI-produced 9+ monomer after ETD (Fig. 4d) and after ETnoD/CAD (Fig. 4e) exhibit a remarkable similarity to those produced from the ejected monomer (Fig. 4b and 4c). The relative abundances of ETD products, as well as the regions that are fragmented are nearly identical between the two, indicating similarities in both secondary and tertiary protein structure. The similar protein structures of both the ejected monomer and the ESI-produced molecular ions can be attributed to rapid gas-phase rearrangement of either the protein structure or the spatial distribution of protons in the relatively high pressure (~4 mTorr He) in the ion trap. The rearrangement of conformers at higher pressures was also observed with the charge-reduced dimers and discussed in section 3.1.

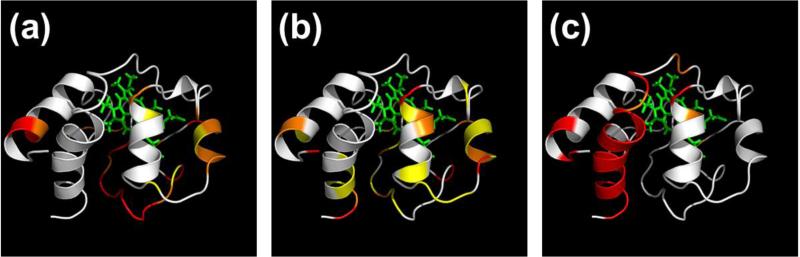

Mapping the dimer ETD fragment ion yields onto the crystal structure of monomeric cytochrome c (Fig. 5a) indicates increased dimer ETD cleavage in the disordered region (residues 30-40) at the bottom center of the figure when compared to that of the ejected monomer (Fig. 5b). On the other hand, cleavage products from the ejected monomer after ETnoD/CAD (Fig. 5c) result mostly from the C-terminal α-helix. Whether α-helices are retained in the gas phase, and whether they inhibit electron-based cleavage is still a matter of debate.35-37 However, the apparent refolding of both the ESI-produced and ejected monomers to this state indicates favorable formation of higher-order structures in this domain.

Figure 5.

Mapping ETD fragment ion yields onto the crystal structure of monomeric cytochrome c for (a) the dimer, (b) the ejected monomer, and (c) the ejected monomer after ETD, isolation of the singly reduced (ETnoD) molecular ion, and gentle activation by CAD. All fragment yields were normalized to the most abundant peak of the spectrum, which was set to 1; red indicates a range of 0.1-1, orange: 0.03-0.1, yellow: <0.03, white: no fragments observed.

3.4 Asymmetric Charge Partitioning of ETD Fragment Ions

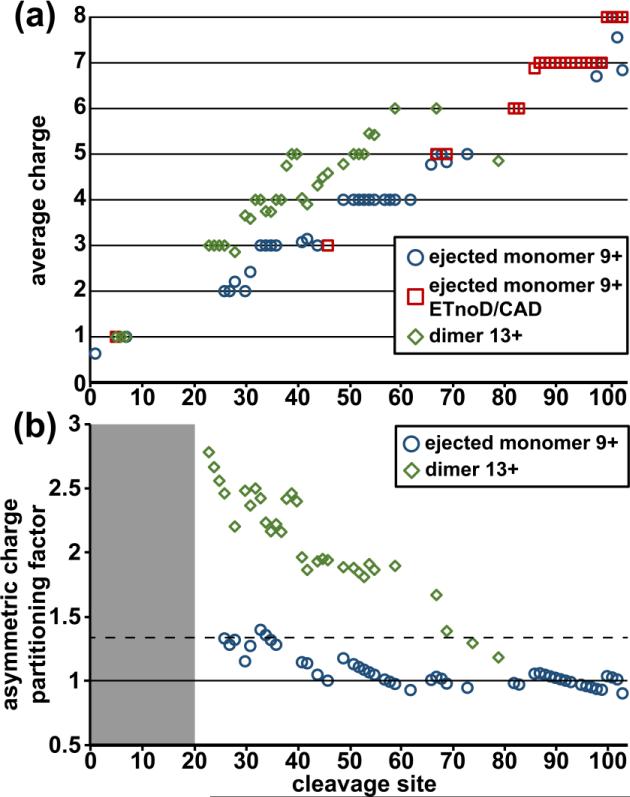

The intensity-weighted average charge of site-specific ETD fragmentation products originating from the intact dimer, the ejected monomer, and the ejected monomer after ETnoD/CAD are shown in Fig. 6a. The two z-fragments observed from the dimer were not included; for those from the ejected monomer, the complementary charge was used assuming one proton was neutralized during fragmentation (8 - z-fragment charge). Therefore, the charge value indicates the average number of charges found on the N-terminal cleavage product of a fragmentation event.

Figure 6.

(a) The intensity-weighted average charge of fragment ions observed from each cleavage site for ETD products originating from the intact dimer, the ejected monomer, and the ejected monomer after ETnoD/CAD of cytochrome c (see key for designations). (b) The asymmetric charge partitioning factor (APCF) calculated for each fragment ion. The dashed horizontal line indicates the average value for monomer ejection; an APCF value of 1 (i.e., symmetric charge partitioning) is indicated with the solid horizontal line. Only fragment ions with cleavage sites >20 are considered.

Determination of the ACPF described in section 3.2 for each fragmentation product is shown in Fig. 6b. Here, fragmentation from both ETD and ETnoD/CAD of the ejected monomer are considered together. Unlike in Fig. 6a, the charge of fragment ions here are considered to contain the charge neutralized during the ETD process, and the monomer and dimer charges are considered before neutralization (9+ and 13+, respectively). For simplicity, the mass of each fragment is determined by the number of residues, instead of the molecular mass of the fragment. A solid horizontal line at ACPF = 1 is shown to indicate symmetric charge partitioning, while the dashed line at ACPF = 1.3 indicates the magnitude of ACP during monomer ejection from the 13+ dimer.

Despite the 28% decrease of charge per residue of the dimer when compared to the ejected monomer, many of the dimer's fragment ions dissociate with a higher charge than those from the monomer. The corresponding ACPF of these fragment ions accounts for these factors and indicates the strength of the effect: at cleavage site 28, fragments dissociate with an ACPF of 2.8, more than double that observed for the same ETD fragment ions generated from the ejected monomer. While the ACPF trends lower at larger fragment sizes, it remains ~1 higher than that from fragments of the ejected monomer, indicating a significant increase in the effect. A similar effect was also briefly described for native ECD fragments.17

In order to determine the portion of the ACP that can be attributed to differential charging of the iron atom in the heme group, we examined the deconvoluted ion mass of the c28 fragment ion at both 2+ and 3+ from the dimer, the ejected monomer, and the ESI-produced monomer (Supplementary Fig. 3). Fragment masses correspond to the unambiguous addition of a proton between the 2+ and 3+ from all of the precursors, indicating that the observed changes in charge state are due to protonation, instead of oxidation of the heme iron. The large ACPF can therefore be directly attributed to proton transfer.

We propose two potential causes for the increased ACPF in ETD product ions: either the charges have asymmetrically partitioned prior to ETD fragmentation, or the charges are transferred after fragmentation and before ejection from the complex. The Coulombic repulsion between protons makes the former unlikely. In the latter, we postulate that the electron transfer event occurs almost instantaneously, cleaving the protein backbone. This is characteristic of a non-ergodic process.12 However, these fragment ions do not dissociate immediately, and remain attached to the protein complex through non-covalent interactions. Collisions with residual gas in the ion trap gently activate the fragment-dimer complex causing the fragment to elongate at which point additional charge is transferred in a similar process to that of monomer ejection. Charge transfer at this stage must either occur through space, or through the non-covalent interactions between the fragment and the complex; the covalent backbone bond has already been broken. The mobilized charges, likely driven to regions with the lowest charge density, account for the gradual increase in charge found for cleavage sites 28-60 in Fig. 6a. When the c-type fragment ion eventually leaves the complex, the process is highly asymmetrical and creates products with high charge density where ACPF is >>1 (Fig. 6b).

4. Conclusions

We introduced a simple metric, the asymmetric charge partitioning factor, or ACPF, to quantify the extent of charge partitioning occurring as protein complexes break apart in the gas phase. Using the ACPF metric, we found that ACP of the cytochrome c dimer and the β-amylase tetramer are not dependent on precursor charge when dissociated with CAD at ion-trap pressures. Further, ETD product ions indicate a similar, but not identical higher-order structure of the intact dimer and ejected monomer, and that the ejected monomer has undergone new folding. Surprisingly, ETD products from the dimer are observed with higher charge, and exhibit a higher ACPF than those from the monomer, which has a higher charge-density precursor. Thus, we provide compelling evidence that ETD products not only undergo ACP, but can absorb even more charge density than the ejected monomer when normalized for their mass. Future studies can test this effect on other systems and other solution conditions and refine fragment-ion specific surface area models for better understanding and use of the diverse tandem MS methods in structural biology.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We present the asymmetric charge partitioning factor (ACPF).

We apply ACPF to monomer ejection of cytochrome c dimer and beta amylase tetramer.

ETD indicates similar cytochrome c ESI-monomer and ejected monomer structures.

ETD fragment ions from the dimer undergo asymmetric charge partitioning.

ETD fragment ions from dimer can have 2-fold higher ACPF than ejected monomer.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the W. M. Keck foundation. LF is funded through an Early Postdoc Mobility Fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation. OSS would like to thank the NSF GRFP for a predoctoral fellowship (#2014171659) and NLK acknowledges the NIH (GM067193) for further support of this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yang Y, Barendregt A, Kamerling JP, Heck AJR. Analytical Chemistry. 2013;85:12037. doi: 10.1021/ac403057y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muneeruddin K, Thomas JJ, Salinas PA, Kaltashov IA. Analytical Chemistry. 2014;86:10692. doi: 10.1021/ac502590h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loo JA. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 1997;16:1. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1997)16:1<1::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrera NP, Di Bartolo N, Booth PJ, Robinson CV. Science. 2008;321:243. doi: 10.1126/science.1159292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie Y, Zhang J, Yin S, Loo JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14432. doi: 10.1021/ja063197p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin AC, Bosche M, Krause R, Grandi P, Marzioch M, Bauer A, Schultz J, Rick JM, Michon AM, Cruciat CM, Remor M, Hofert C, Schelder M, Brajenovic M, Ruffner H, Merino A, Klein K, Hudak M, Dickson D, Rudi T, Gnau V, Bauch A, Bastuck S, Huhse B, Leutwein C, Heurtier MA, Copley RR, Edelmann A, Querfurth E, Rybin V, Drewes G, Raida M, Bouwmeester T, Bork P, Seraphin B, Kuster B, Neubauer G, Superti-Furga G. Nature. 2002;415:141. doi: 10.1038/415141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Abdel-Wahab O, Guglielmelli P, Patel J, Caramazza D, Pieri L, Finke CM, Kilpivaara O, Wadleigh M, Mai M, McClure RF, Gilliland DG, Levine RL, Pardanani A, Vannucchi AM. Leukemia. 2010;24:1302. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Cui W, Wen J, Blankenship RE, Gross ML. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2010;21:1966. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrera NP, Isaacson SC, Zhou M, Bavro VN, Welch A, Schaedler TA, Seeger MA, Miguel RN, Korkhov VM, van Veen HW, Venter H, Walmsley AR, Tate CG, Robinson CV. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:585. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belov ME, Damoc E, Denisov E, Compton PD, Horning S, Makarov AA, Kelleher NL. Anal Chem. 2013;85:11163. doi: 10.1021/ac4029328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner OS, Do Vale LHF, Catherman AD, Havugimana PC, Sousa M. V. d., Compton PD, Kelleher NL. Analytical Chemistry. 2015;87:3032. doi: 10.1021/ac504678d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zubarev RA, Kelleher NL, McLafferty FW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:3265. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuker K, Oh H, Horn DM, Cerda BA, McLafferty FW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6407. doi: 10.1021/ja012267j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skinner OS, McLafferty FW, Breuker K. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:1011. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner O, Breuker K, McLafferty F. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2013;24:807. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Wongkongkathep P, Van Orden SL, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Loo JA. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;25:2060. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0928-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breuker K, McLafferty FW. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2003;42:4900. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breuker K, McLafferty FW. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2005;44:4911. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Light-Wahl KJ, Schwartz BL, Smith RD. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1994;116:5271. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz B, Bruce J, Anderson G, Hofstadler S, Rockwood A, Smith R, Chilkoti A, Stayton P. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1995;6:459. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00191-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jurchen JC, Williams ER. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:2817. doi: 10.1021/ja0211508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rostom AA, Robinson CV. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 1999;9:135. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)80018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jurchen JC, Garcia DE, Williams ER. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2004;15:1408. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benesch JLP, Aquilina JA, Ruotolo BT, Sobott F, Robinson CV. Chemistry & Biology. 2006;13:597. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abzalimov RR, Frimpong AK, Kaltashov IA. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2006;253:207. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones CM, Beardsley RL, Galhena AS, Dagan S, Cheng G, Wysocki VH. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:15044. doi: 10.1021/ja064586m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wanasundara SN, Thachuk M. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2007;18:2242. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sciuto S, Liu J, Konermann L. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2011;22:1679. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Syka JEP, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:9528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadygov RG, Good DM, Swaney DL, Coon JJ. Journal of proteome research. 2009;8:3198. doi: 10.1021/pr900153b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strohalm M, Kavan D, Novák P, Volný M, Havlíček V. r. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82:4648. doi: 10.1021/ac100818g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamidane H, He H, Tsybin O, Emmett M, Hendrickson C, Marshall A, Tsybin Y. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2009;20:1182. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith RD, Light-Wahl KJ, Winger BE, Loo JA. Organic Mass Spectrometry. 1992;27:811. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prell JS, Demireva M, Oomens J, Williams ER. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:1232. doi: 10.1021/ja808177z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breuker K, Bruschweiler S, Tollinger M. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2011;50:873. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyttenbach T, Bowers MT. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2011;115:12266. doi: 10.1021/jp206867a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breuker K, McLafferty FW. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:18145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.