Abstract

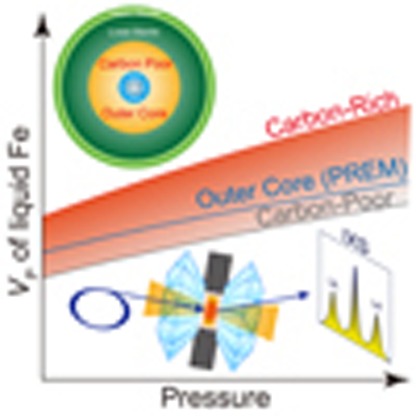

The relative abundance of light elements in the Earth's core has long been controversial. Recently, the presence of carbon in the core has been emphasized, because the density and sound velocities of the inner core may be consistent with solid Fe7C3. Here we report the longitudinal wave velocity of liquid Fe84C16 up to 70 GPa based on inelastic X-ray scattering measurements. We find the velocity to be substantially slower than that of solid iron and Fe3C and to be faster than that of liquid iron. The thermodynamic equation of state for liquid Fe84C16 is also obtained from the velocity data combined with previous density measurements at 1 bar. The longitudinal velocity of the outer core, about 4% faster than that of liquid iron, is consistent with the presence of 4–5 at.% carbon. However, that amount of carbon is too small to account for the outer core density deficit, suggesting that carbon cannot be a predominant light element in the core.

The composition of the Earth's core, particularly the light elements present, is not well constrained. Here, the authors report sound velocities of liquid iron-carbon alloy as measured at very high pressures using inelastic X-ray scattering and suggest that carbon cannot be predominant in the outer core.

The composition of the Earth's core, particularly the light elements present, is not well constrained. Here, the authors report sound velocities of liquid iron-carbon alloy as measured at very high pressures using inelastic X-ray scattering and suggest that carbon cannot be predominant in the outer core.

Sound velocity and density are important observational constraints on the chemical composition of the Earth's core. While properties of solid iron alloys have been extensively examined by laboratory studies to core pressures (>136 GPa)1,2,3, little is known for liquid alloys because of experimental difficulties. The core is predominantly molten, and the longitudinal wave (P-wave) velocity of liquid iron alloy is the key to constraining its composition. However, previous static high-pressure and -temperature (P–T) measurements of liquid iron alloys were performed only below 10 GPa using large-volume presses4,5,6. Shock wave experiments have been carried out at much higher pressures but only along a specific Hugoniot P–T path7,8.

Carbon is one of the possible light alloying components in the core because of its high cosmic abundance and strong chemical affinity with liquid iron9. Its high metal/silicate partition coefficients indicate that thousands of parts per million to several weight percent of carbon could have been incorporated into the core during its formation9,10,11. In addition, recent experimental and theoretical studies12,13 have suggested that solid Fe7C3 may explain the properties of the inner core, in particular its high Poisson's ratio14,15, supporting the presence of carbon in the core.

In this study, we determine the P-wave velocity (VP) (equivalent to bulk sound velocity, VΦ, in a liquid) of liquid Fe84C16 at high P–T based on inelastic X-ray scattering (IXS) measurements. Combined with its density data at 1 bar (ref. 16) both velocity and density (ρ) profiles of liquid Fe84C16 along adiabatic compression are obtained. They are compared with seismological observations, indicating that both VP and ρ in the Earth's outer core are not explained simultaneously by liquid Fe–C.

Results

Longitudinal wave velocity measurements

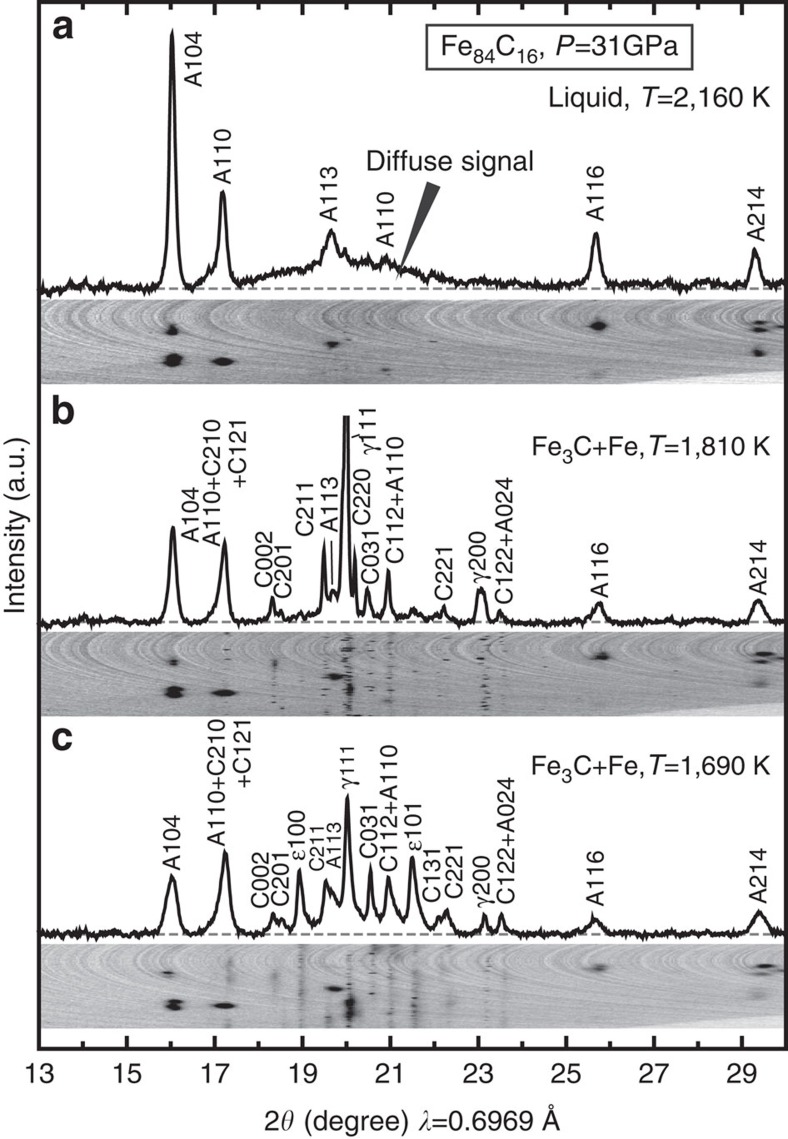

We collected the high-resolution IXS spectra from liquid Fe84C16 (4.0±0.3 wt.% carbon) at static high P–T using both resistance- and laser-heated diamond-anvil cells (Methods; Fig. 1). The starting material was synthesized beforehand as a mixture of fine-grained Fe and Fe3C at 5 GPa and 1,623 K in a multi-anvil apparatus. Experimental P–T conditions were well above the eutectic temperature in the Fe–Fe3C binary system (Supplementary Fig. 1). The carbon concentration in the eutectic liquid is known to be 3.8–4.3 wt.% at 1 bar to 20 GPa (ref. 17), almost identical to the composition of our sample. Above 20 GPa, we heated the sample to temperatures comparable or higher than the melting temperature of Fe3C, a liquidus phase in the pressure range explored, assuring a fully molten sample. The molten state of the specimen was carefully confirmed, before and after the IXS measurements, by the absence of diffraction peaks from the sample (Fig. 2). We sometimes, depending on a sample volume, were also able to observe the diffuse diffraction signal typical of a liquid.

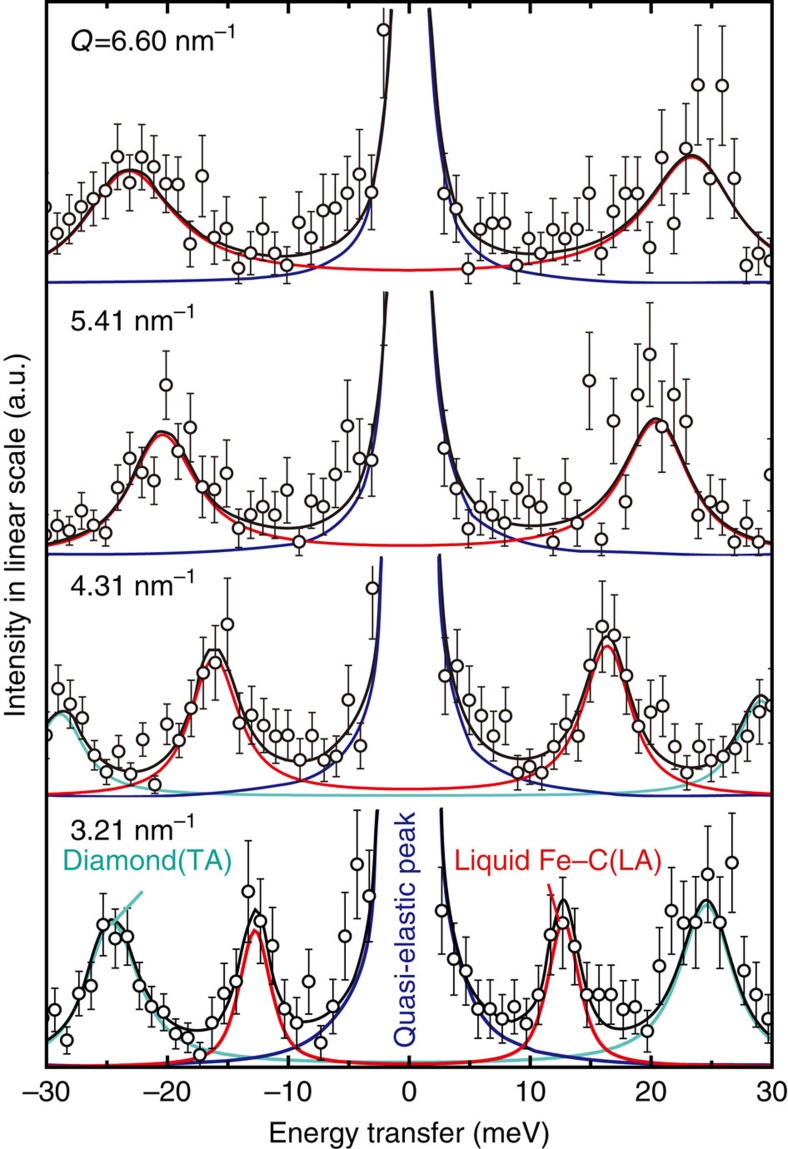

Figure 1. Typical inelastic X-ray scattering spectra.

These data were collected at 26 GPa and 2,530 K at momentum transfers Q, as indicated. The spectra include three components: a quasi-elastic peak near zero energy transfer (blue), longitudinal acoustic (LA) phonon mode of liquid Fe84C16 (red), and transverse acoustic (TA) phonon mode of diamond (turquoise).

Figure 2. X-ray diffraction spectra before and after melting.

They were collected at 2,160 K (a), 1,810 K (b) and 1,690 K (c) during heating at 31 GPa. The starting material was composed of Fe (ɛ or γ) and Fe3C (c), and the peaks of Al2O3 (a) were from a thermal insulator. The coexistence of ɛ- and γ-Fe phases at 1,610 K was due to a sluggish solid–solid phase transition49 and the peaks from the ɛ-phase were lost at 1,810 K. All sample peaks disappeared between 1,810 and 2,160 K. In addition, the background was enhanced slightly, indicating a diffuse scattering signal from a liquid sample.

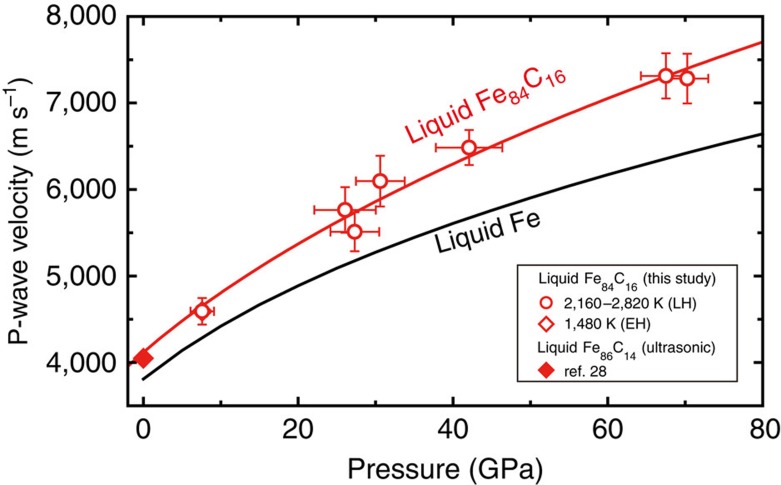

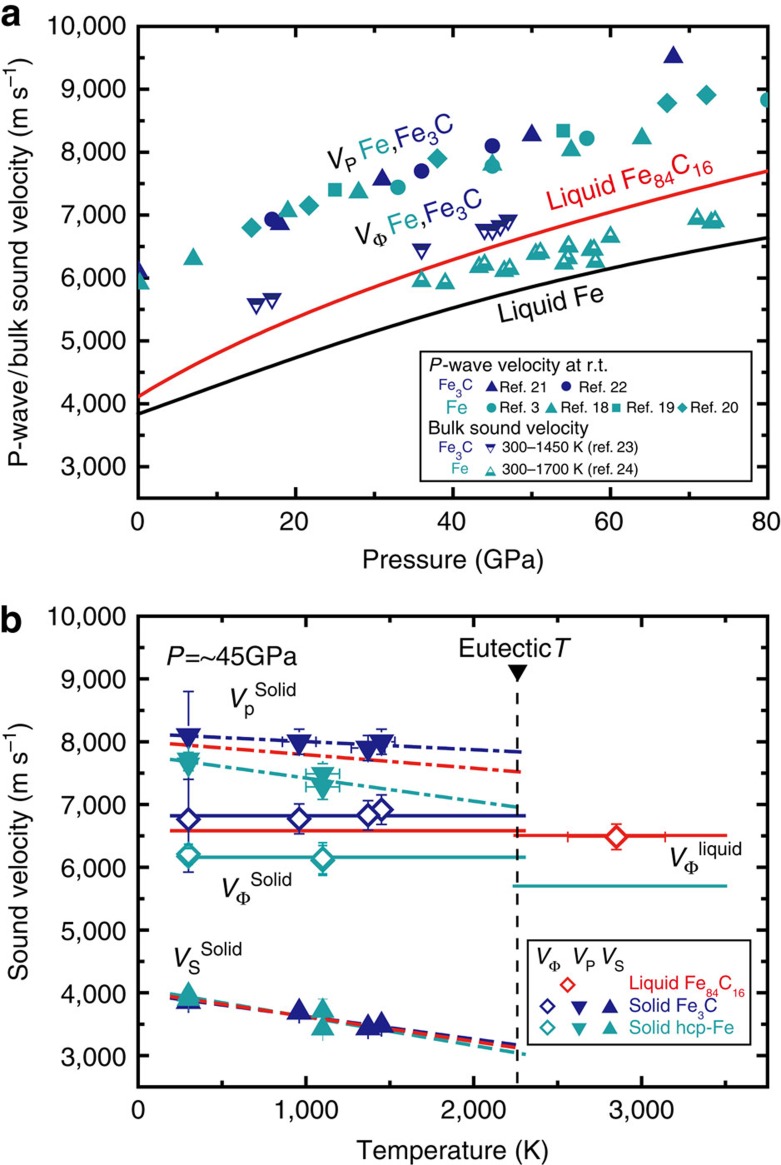

The VP of liquid Fe84C16 was determined between 7.6 and 70 GPa (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1) from dispersion curves for a range of momentum transfer (Fig. 4). It was found to be 15–30% smaller than that of solid Fe (refs 3, 18, 19, 20) and Fe3C (refs 21, 22, 23; note that a starting material in the present experiments was a mixture of these solid phases) (Fig. 5), confirming that we measured a liquid sample. The velocities of a fictive solid Fe84C16 alloy are also estimated assuming a linear velocity change between Fe (ref. 24) and Fe3C (ref. 23) indicating that VP drops by 13% upon melting at 2,300 K, a eutectic temperature at 45 GPa (ref. 17). Such a velocity change is comparable to that expected for pure Fe. The difference in VΦ between solid and liquid Fe84C16 is very small (1.8%). On the other hand, the VP of our liquid Fe84C16 sample is 3–14% faster at 8–70 GPa than that of liquid Fe determined by shock-wave study8 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Compressional wave velocity of liquid Fe84C16.

Open circles, obtained by laser-heated DAC; open diamond, by external-resistance-heated DAC. The data at 1 bar is from ultrasonic measurements28 (closed diamond). The red curve represents a thermodynamical fitting result for liquid Fe84C16, compared with the velocity of liquid Fe (black curve)8.

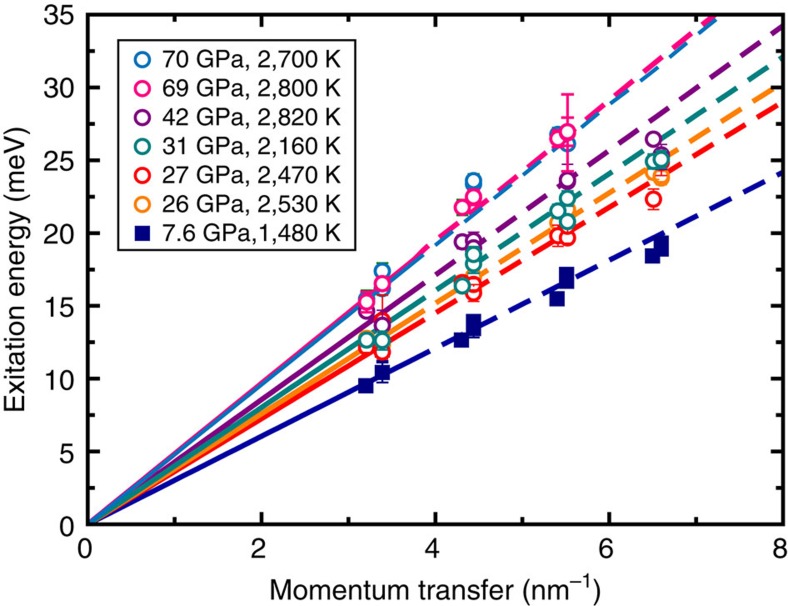

Figure 4. Longitudinal acoustic phonon dispersion of liquid Fe84C16.

The dispersion data were obtained at pressures from 7.6 to 70 GPa. Only data collected with the low momentum transfer (<3.5 nm−1) were used to determine the velocity to avoid possible anomalous dispersion for liquid (see Methods).

Figure 5. Comparison of velocities between liquid and solid Fe–C alloys.

(a), P-wave velocities (VP) and bulk sound velocities (VΦ) of solid Fe (turquoise)3,18,19,20,24 and Fe3C (blue)21,22,23 were determined by previous IXS and nuclear inelastic scattering (NIS) measurements. The VP for liquid Fe is from shock-wave study8. (b), Temperature effects on the sound velocities of Fe–C alloys at ∼45 GPa. The VP (= VΦ) of liquid Fe84C16 and liquid Fe is from the present work at 42 GPa and shock-wave data8, respectively. The VP, shear velocity (VS), and VΦ for solid Fe and Fe3C were reported by NIS measurements23,24. Red lines for fictional solid Fe84C16 are estimated from a linear relationship between Fe and Fe3C.

Earlier ultrasonic measurements performed below 10 GPa reported a change in VP by <2–3% per 1,000 K for liquid Fe–S alloys4,5. Theoretical calculations25,26,27 and shock compression data8 on liquid Fe and Fe–S alloy demonstrated even smaller effects above 100 GPa (<0.5% by 1,000 K). It is therefore very likely that the VP of liquid Fe84C16 is also not sensitive to temperature with the temperature effect much smaller than the uncertainty in the present velocity determinations (±3%).

Thermodynamical equation of state

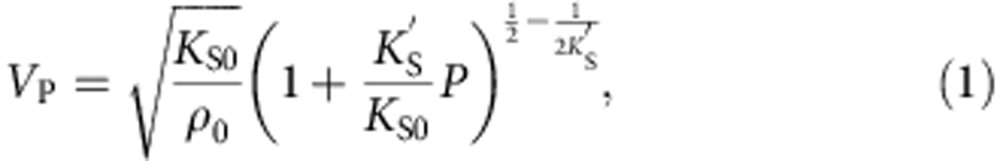

VP of a liquid can be described using the Murnaghan equation of state4 (Methods) as;

|

where KS and K′S are adiabatic bulk modulus and its pressure derivative, respectively (zero subscripts denote values at 1 bar and T=T0). Here, consistent with the discussion above, we neglect the temperature dependence of our VP data, while ρ0 is taken to be temperature dependent16 (Methods). We fit equation (1) to our P–VP data for liquid Fe84C16 and find KS0=110±9 GPa and K′S=5.14±0.30 when T0=2,500 K (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The choice of T0 and, accordingly, the variation in ρ0 practically changed KS0 and K′S0 as (∂KS0/∂T)=−9.4 × 10−3 GPa K−1 and (∂K′S0/∂T) =−2.7 × 10−4 K−1. Our value for KS0 is similar to that for liquid iron8 but for K′S is higher than that for pure iron, K′S=4.7. This suggests that liquid Fe84C16 becomes progressively stiffer than liquid Fe with increasing pressure. We also found VP0=4,121±177 m s−1 for liquid Fe84C16 from KS0 and ρ0, in good agreement with a previous study28 of liquid Fe86C14 at 1 bar (4,050 m s−1) and faster than VP0=3,860 m s−1 for liquid Fe (ref. 8).

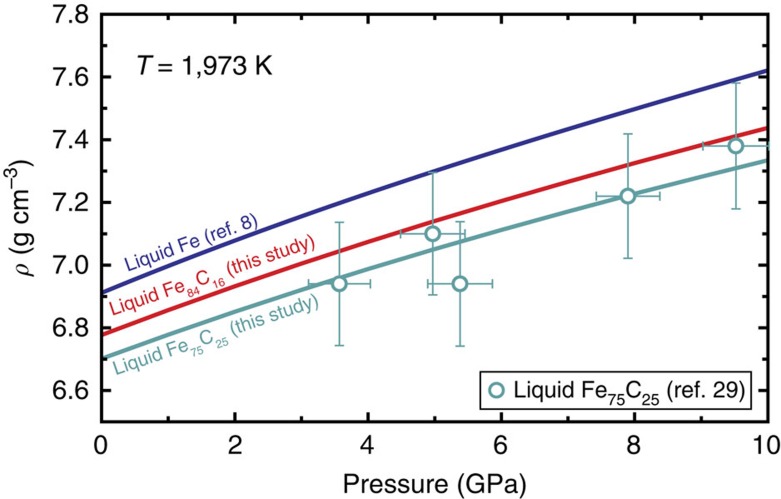

To compare the present results with earlier density measurements of liquid Fe–C alloys at high pressure29,30 the isothermal bulk modulus for liquid Fe84C16 is estimated to be KT0=100 (82) GPa at 1,500 K (2,500 K) from our determination of KS combined with Grüneisen parameter γ0=1.74 (ref. 8) and thermal expansion coefficient16 (Methods). When applying CP/CV=1.125 at 1,820 K for liquid Fe86C14 derived from theoretical calculations31, KT0=106–98 GPa is obtained at the same temperature range. These KT0 values for liquid Fe84C16 are similar to KT0=95–63 GPa for liquid Fe at 1,500–2,500 K (ref. 8) On the other hand, they are significantly larger than KT0=55.4 GPa for liquid Fe86C14 at 1,500 K and KT0=50 GPa for liquid Fe75C25 at 1,973 K from previous density measurements29,30. However, the calculated density for Fe84C16 using the present EoS are in reasonable agreement with the previous density measurements of Fe75C25 (ref. 29) (Fig. 6). The disagreement of elastic parameters with such earlier experiments may be attributed either to the limited pressure range of the previous density determinations, or to a different structure or magnetic (or electronic) change in the state of the liquid Fe–C at low pressure, as has been suggested from the change in compressional behaviour of liquid Fe78C22 around 5 GPa (ref. 6). Our data were collected above 7.6 GPa, so that the physical properties of liquid Fe–C obtained here should be more applicable to the Earth's core.

Figure 6. Comparison with previous density measurements.

Blue and red curves demonstrate calculated densities at 1,973 K for liquid Fe (ref. 8) and Fe84C16 (present study). The density of liquid Fe75C25 (turquoise curve) is estimated assuming linear compositional dependence between pure Fe and Fe75C25, which shows good agreement with the previous measurements at 1,973 K (ref. 29).

ρ of liquid Fe84C16 is then given, using the elastic parameters determined above, by;

|

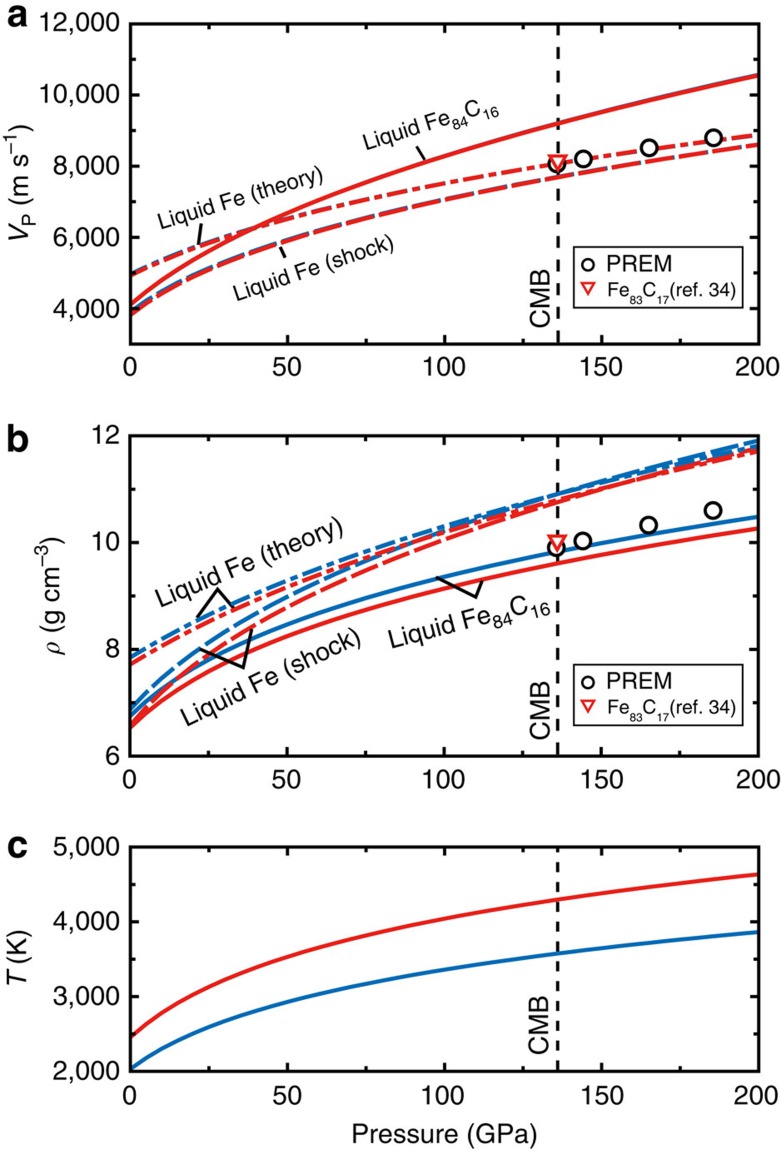

Equations (1) and (2) give the VP and ρ profiles for adiabatic compression (Methods), assuming γ0=1.74, the same as that of liquid Fe (ref. 8) (Fig. 7). We find VP=9,200 m s−1 and ρ=9.82–9.61 g cm−3 at the core-mantle boundary (CMB) for TCMB=3,600–4,300 K (refs 32, 33) This indicates that VP of liquid Fe84C16 is 19.6% faster than that of liquid Fe at the CMB8, implying that the addition of 1 at.% carbon increases the VP of liquid Fe by 1.2%. The extrapolation of the present experimental data using the Murnaghan equation of state may overestimate the VP by 2−4% at the CMB (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3), but, even if this is the case, 1 at.% carbon enhances the VP of liquid Fe by as large as 0.8%. Indeed, the effect of carbon is much larger than a recent theoretical prediction of only 0.2% increase in velocity per 1 at.% carbon at 136 GPa (ref. 34). On the other hand, our data show that the incorporation of 1 at.% carbon reduces the density of liquid Fe by 0.6–0.7%, while theory suggested only 0.3% density reduction by 1 at.% carbon34.

Figure 7. Velocity and density of liquid Fe84C16 extrapolated to core pressures.

The P-wave velocity (a) and density (b) profiles of liquid Fe84C16 are calculated along two adiabatic temperature curves (c) of 3,600 K (blue) and 4,300 K (red) at the CMB. Those for liquid Fe are from shock-compression experiments8 and theoretical calculations26. The velocity and density for liquid Fe83C17 at the CMB (4,300 K) are by theory34. PREM denotes seismologically deduced Preliminary Reference Earth model35.

Discussion

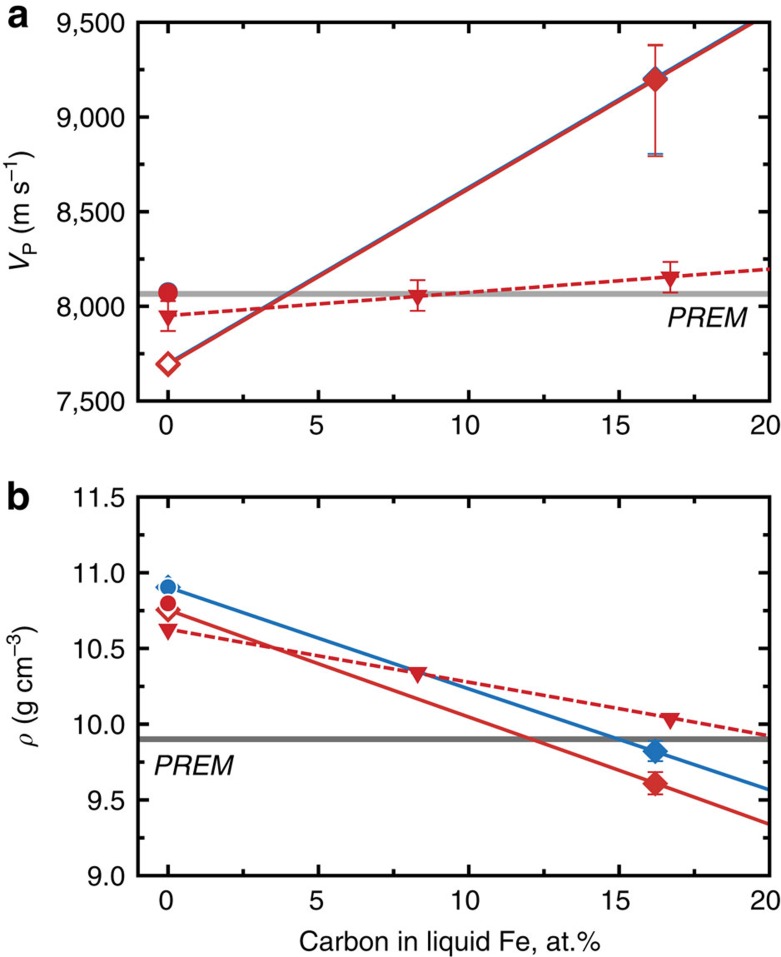

We now compare the sound velocity and density of liquid Fe84C16 and liquid Fe with the seismologically based PREM model35 for the outer core (Fig. 8). The VP and ρ of liquid Fe are 4.6% slower and 10.1–8.6% denser, respectively, than the PREM at the CMB (3,600–4,300 K). To match the PREM values, considering the uncertainty of data extrapolation to higher pressures (Supplementary Note 1), only 5.2–4.0 at.% (1.2–0.9 wt.%) carbon is required to match the velocity, whereas 15.4–12.0 at.% (3.8–2.9 wt.%) carbon is necessary to account for the density. Therefore, carbon cannot be a predominant light element in the outer core.

Figure 8. Effect of carbon on the velocity and density of liquid Fe at 136 GPa.

(a) Velocity and (b) density for liquid Fe84C16 at TCMB=4,300 K (red) and 3,600 K (blue). Present results (closed diamonds, solid curves) are compared with theoretical calculations34 (triangles, broken curve). The data for pure Fe are from shock compression study8 (open diamonds) and theoretical calculations26 (closed circles). PREM denotes seismological observations35 at the CMB.

These results suggest there is <5.2 at.% (1.2 wt.%) carbon in the outer core, consistent with the previous cosmochemical and geochemical arguments. In particular, the silicate portion of the Earth exhibits much higher 13C/12C isotopic ratio than that of Mars, Vesta and chondrite meteorites, as may be attributed to a strong enrichment of 12C in core-forming metals9. The carbon isotopic fractionation that occurred during continuous core-formation process proposed previously36,37 will give a reasonable 13C/12C ratio in the silicate Earth, and yields 1 wt.% carbon in the core9. In addition, Wood et al.9 demonstrated that carbon strongly affects the chemical activity of Mo and W in liquid metal, so that their abundance in the mantle can be explained by partitioning between silicate melt and core-forming metal with ∼0.6 wt.% carbon. It has been repeatedly suggested that the inner core may be composed of Fe7C3, which accounts for high Poisson's ratio observed14,15. The crystallization of solid Fe7C3 from a liquid outer core with <1.2 wt.% carbon may still be possible if sulfur is also included in the core38.

Methods

High P–T generation

Molten Fe–C alloy was obtained at high P–T in an external-resistance-heated (EH) or laser-heated (LH) diamond-anvil cell (DAC; Supplementary Table 1) using facilities installed at SPring-8. A disc of pre-synthesized Fe84C16 sample, 20–25 μm thick and 100–120 μm in diameter, was loaded into a hole of a rhenium gasket, together with two 12–17 μm thick single-crystal Al2O3 sapphire discs that served as both thermal and chemical insulators. The sample was compressed with 300 μm culet diamond anvils to a pressure of interest before heating.

In LH-DAC experiments, the sample was heated at high pressure from both sides by using two 100 W single-mode Yb fibre lasers (YLR-100-AC, IPG Photonics Corp.). The Gaussian-type energy distribution of the laser beam was converted into flat-top one with a refractive beam shaper (GBS-NIR-H3, Newport Corp.). A typical laser spot was 50–70 μm in diameter on the sample, much larger than X-ray beam size (∼17 μm). We determined temperature by a spetroradiometric method, and its variations within the area irradiated by X-rays and fluctuations during IXS measurements were <±10%. The pressure was obtained from the equation of state for Fe3C (ref. 39) from the lattice constant observed before melting at 1,800–2,500 K. Its error was derived from uncertainties in both temperature and the volume of Fe3C. A typical image of a sample recovered after the laser heating experiment at 70 GPa and 2,700 K is given in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Only run #FeC08 was conducted in an EH-DAC. The whole sample was homogeneously heated by a platinum-resistance heater placed around the diamonds. The temperature was obtained with a Pt-Rh (type-R) thermocouple whose junction was in contact with the diamond near a sample chamber. The temperature uncertainty was <20 K. We determined the pressure based on the Raman shift of a diamond anvil40 before heating at 300 K, whose uncertainty may be as much as ±20%.

IXS measurements

The sound velocity of liquid Fe–C alloy was determined in the DAC by high-resolution IXS spectroscopy at the beamline BL35XU, SPring-8 (ref. 41). Both LH- and EH-DACs were placed into vacuum chambers to minimize background scattering by air. The measurements were carried out with ∼2.8 meV energy resolution using Si (999) backscattering geometry at 17.79 keV. The experimental energy resolutions were determined using scattering from Polymethyl–methacrylate. The incident X-ray beam was focused to about 17 μm size (full width at half maximum) in both horizontal and vertical directions by using Kirkpatrick–Baez mirrors42. The X-ray beam size was much smaller than heated area (50–70 μm for LH-DAC). Scattered photons were collected by an array of 12 spherical Si analyzers leading to 12 independent spectra at momentum transfers (Q) between 3.2 and 6.6 nm−1 with a resolution ΔQ ∼0.45 nm−1 (full width) that was set by slits in front of the analyzer array. The energy transfer range of ±30 (or −10 to ±30) meV was scanned for 1–3 h. Before and after IXS data collections, sample melting was confirmed by X-ray diffraction data (Fig. 2) that was collected, in situ, by switching a detector to a flat panel area detector (C9732DK, Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.)43.

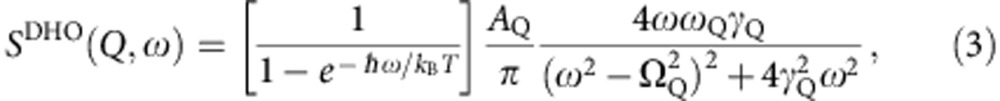

The IXS spectra included three (sometimes five) peaks (Fig. 1) of Stokes and anti-Stokes components of the longitudinal acoustic (LA) phonon mode from the sample (sometimes also from a diamond), and a quasi-elastic contribution near zero energy transfer. These spectra were fitted with the damped harmonic oscillator (DHO) mode44 for acoustic phonon modes and with Lorenzian function for quasi-elastic peaks convolved by experimental resolution function. The DHO model function can be described as;

|

where AQ, ΓQ, ΩQ, kB and ħ are the amplitude, width, and energy of inelastic modes, Boltzmann constant and Planck constant, respectively. In the fitting, temperature T was fixed at a sample temperature obtained by a spetroradiometric method or a thermocouple. The excitation energy modes appearing at both Stokes and anti-Stokes sides correspond to the phonon creation and annihilation, respectively. With increasing temperature, as given by the Bose function in equation (3), the intensities of such Stokes and anti-Stokes peaks become similar to each other. A symmetric shape of the present IXS spectra therefore assures that the IXS signals originated from a high-temperature area.

The peak at a finite energy transfer gives the frequency of each mode (Fig. 1). The excitation energies for the LA phonon mode of liquid Fe84C16 obtained in a pressure range of 7.6–70 GPa are plotted as a function of momentum transfer (Q) in Fig. 4. The compressional sound wave or P-wave velocity (VP) corresponds to the long-wavelength LA velocity at Q→0 limits;

|

We made a linear fit to the data obtained at low Q below 3.5 nm−1 to determine the P-wave velocity (Supplementary Table 1), because positive dispersion can appear at higher Q>>3 nm−1 (ref. 45). For comparison, the results based on a sine-curve fit to all Q-range data, as is usually applied for polycrystalline samples in similar high-pressure IXS measurements46, are also given in Supplementary Table 1. In general, the error bars of the two determinations of VP overlap, though the sine fit to large Q does give slightly larger VP, as would qualitatively be expected from previous measurements on liquid iron47.

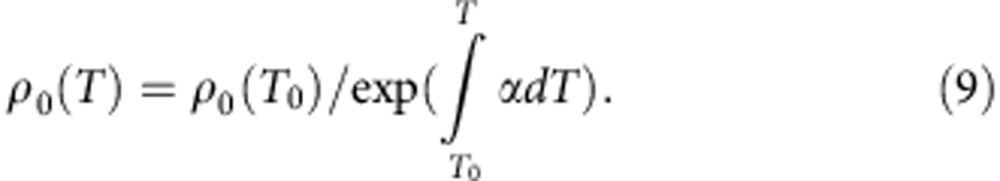

Equation of state for liquid Fe84C16

We constructed an equation of state (EoS) for liquid Fe84C16 to extrapolate the present VP data and to estimate its density at the core pressure range. VP of liquid can be written as;

|

The pressure dependence of KS is assumed to be

|

where K′S is the pressure derivative of KS and pressure and subscript zero indicates a value at 1 bar. The adiabatic Murnaghan EoS can be described as (for example, ref. 4);

|

Equation (5) is thus rewritten as;

|

The temperature effect on ρ0 can be expressed by;

|

The thermal expansion coefficient α is also dependent on temperature as;

|

where a and b are constants. Previous density measurements16 of liquid Fe–C alloys at 1 bar give a=6.424 × 10−5 K−1 and b=0.606 × 10−8 K−2 for liquid Fe84C16 using ρ0=6.505 g cm−3 at T0=2,500 K as a reference. The result of fitting equation (8) to the present P−VP data is given in Fig. 3.

Isothermal bulk modulus

We estimate isothermal bulk modulus KT from isentropic bulk modulus KS in two ways. The relationship between these two is described as follows;

|

where CP and CV are heat capacities at constant pressure and volume, respectively. Although γ for liquid Fe–C alloys is not known, γ0=1.74 has been reported for liquid Fe at 1 bar and 1,811 K (ref. 8) It is close to 1.58 for liquid Fe90O8S2 estimated from the shock compression data set48.

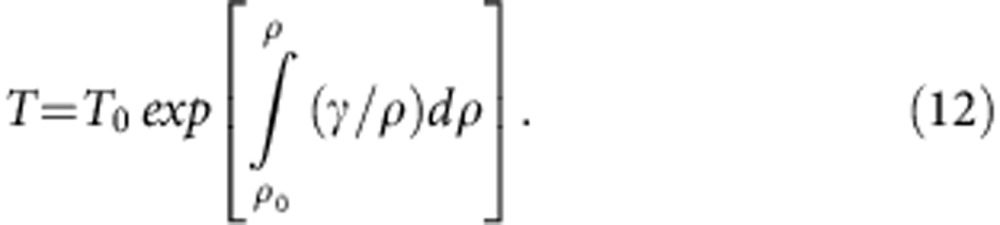

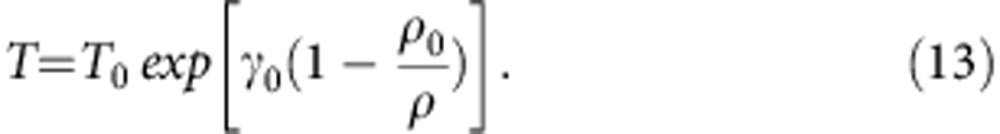

Extrapolation of present data to core pressures

With the EoSs determined above (equations (7) and (8)), we extrapolate the P-wave velocity and density of liquid Fe84C16 to the core pressure range along adiabatic compression, in which temperature is given by;

|

Assuming γ=γ0 × (ρ0/ρ), temperature is simply represented as;

|

γ0 is fixed at 1.74 previously obtained for liquid Fe (ref. 8). Using the temperature dependence of KS0 and ρ0 shown above, we calculate density, velocity and temperature profiles along adiabatic compression with various reference temperatures at the CMB. The adiabatic compression profiles of liquid Fe84C16 for the low (T0=2,045 K and TCMB=3,600 K)32 and high (T0=2,457 K and TCMB=4,300 K)33 temperature cases are calculated in Fig. 7.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Nakajima, Y. et al. Carbon-depleted outer core revealed by sound velocity measurements of liquid iron–carbon alloy. Nat. Commun. 6:8942 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9942 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Fukui for his advice through IXS measurements. H. Uchiyama, D. Ishikawa, N. Murai and Y. Um are acknowledged for their supports during synchrotron experiments and data analyses, and D. Ishikawa and H. Fukui for implementation of the KB setup. Comments from three anonymous reviewers were helpful. All experiments were performed at BL35XU, SPring-8 (Proposal no. 2012B1356, 2013A1541, 2013B1407, 2014A1368, 2014B1271 and 2014B1536).

Footnotes

Author contributions Y.N. synthesized a starting material and performed experiments and data analysis. Y.N., S.I., K.H, T.K., S. Tateno, S. Tsutsui, Y.K. and A.B. were involved in IXS measurements. H.O., S. Tateno, S.I. and Y.N. were involved in developing the laser heating system at the beamline. Y.N., K.H. and A.B. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Badro J. et al. Effect of light elements on the sound velocities in solid iron: implications for the composition of Earth's core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 254, 233–238 (2007) . [Google Scholar]

- Sata N. et al. Compression of FeSi, Fe3C, Fe0.95O, and FeS under the core pressures and implication for light element in the Earth's core. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B09204 (2010) . [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani E. et al. Sound velocity of hexagonal close-packed iron up to core pressures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5089–5094 (2013) . [Google Scholar]

- Jing Z. et al. Sound velocity of Fe-S liquids at high pressure: implications for the Moon's molten outer core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 396, 78–87 (2014) . [Google Scholar]

- Nishida K. et al. Sound velocity measurements in liquid Fe-S at high pressure: Implications for Earth's and lunar cores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 362, 182–186 (2013) . [Google Scholar]

- Sanloup C., van Westrenen W., Dasgupta R., Maynard-Casely H. & Perrillat J.-P. Compressibility change in iron-rich melt and implications for core formation models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 306, 118–122 (2011) . [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. et al. Evidence for an oxygen-depleted liquid outer core of the Earth. Nature 479, 513–516 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson W. W. & Ahrens T. J. An equation of state for liquid iron and implications for the Earth's core. J. Geophys. Res. 99, 4273–4284 (1994) . [Google Scholar]

- Wood B. J., Li J. & Shahar A. Carbon in the core: its influence on the properties of core and mantle. Rev. Miner. Geochem 75, 231–250 (2013) . [Google Scholar]

- Chi H., Dasgupta R., Duncan M. S. & Shimizu N. Partitioning of carbon between Fe-rich alloy melt and silicate melt in a magma ocean – implications for the abundance and origin of volatiles in Earth, Mars, and the Moon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 139, 447–471 (2014) . [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y., Takahashi E., Suzuki T. & Funakoshi K. "Carbon in the core" revisited. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 174, 202–211 (2009) . [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y. et al. Thermoelastic property and high-pressure stability of Fe7C3: implication for iron-carbide in the Earth's core. Am. Mineral. 96, 1158–1165 (2011) . [Google Scholar]

- Mookherjee M. et al. High-pressure behavior of iron carbide (Fe7C3) at inner core conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 116, B04201 (2011) . [Google Scholar]

- Prescher C. et al. High Poisson's ratio of Earth's inner core explained by carbon alloying. Nat. Geosci. 8, 220–223 (2015) . [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. et al. Hidden carbon in Earth's inner core revealed by shear softening in dense Fe7C3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 17755–17758 (2014) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino K., Nishiwaki A. & Hosotani Y. Density of molten Fe-C alloys. J. Jpn Inst. Met. 48, 1004–1010 (1984) . [Google Scholar]

- Fei Y. & Brosh E. Experimental study and thermodynamic calculations of phase relations in the Fe-C system at high pressure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 408, 155–162 (2014) . [Google Scholar]

- Fiquet G., Badro J., Guyot F., Requardt H. & Krisch M. Sound velocities in iron to 110 gigapascals. Science 291, 468–471 (2001) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonangeli D. et al. Simultaneous sound velocity and density measurements of hcp iron up to 93 GPa and 1100 K: an experimental test of the Birch's law at high temperature. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 331-332, 210–214 (2012) . [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z. et al. Sound velocities of Fe and Fe-Si alloy in the Earth's core. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10239–10244 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiquet G., Badro J., Gregoryanz E., Fei Y. & Occelli F. Sound velocity in iron carbide (Fe3C) at high pressure: implications for the carbon content of the Earth's inner core. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 172, 125–129 (2009) . [Google Scholar]

- Gao L. et al. Sound velocities of compressed Fe3C from simultaneous synchrotron X-ray diffraction and nuclear resonant scattering measurements. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 16, 714–722 (2009) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L. et al. Effect of temperature on sound velocities of compressed Fe3C, a candidate component of the Earth's inner core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 309, 213–220 (2011) . [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. et al. Sound velocities of hot dense iron: Birch's law revisited. Science 308, 1892–1894 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vočadlo L., Alfè D., Gillan M. J. & Price G. D. The properties of iron under core conditions from first principles calculations. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 140, 101–125 (2003) . [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H., Tsuchiya T. & Tange Y. The P-V-T equation of state and thermodynamic properties of liquid iron. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 240–252 (2014) . [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto K. et al. Liquid iron-sulfur alloys at outer core conditions by first-principles calculations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6712–6717 (2014) . [Google Scholar]

- Pronin L., Kazakov N. & Filippov S. Ultrasonic measurements in molten iron. Izv. Vuzov. Chernaya Metall 5, 12–16 (1964) . [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki H. et al. Density measurement of Fe3C liquid using X-ray absorption image up to 10 GPa and effect of light elements on compressibility of liquid iron. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B06207 (2010) . [Google Scholar]

- Shimoyama Y. et al. Density of Fe-3.5wt% C liquid at high pressure and temperature and the effect of carbon on the density of the molten iron. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 224, 77–82 (2013) . [Google Scholar]

- Belashchenko D. K., Mirzoev A. & Ostrovski O. Molecular dynamics modelling of liquid Fe-C alloys. High Temp. Mater. Processess 30, 297–303 (2011) . [Google Scholar]

- Nomura R. et al. Low core-mantle boundary temperature inferred from the solidus of pyrolite. Science 343, 522–525 (2014) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzellini S., Dewaele A., Mezouar M., Loubeyre P. & Morard G. Melting of iron at Earth's inner core boundary based on fast X-ray diffraction. Science 340, 464–466 (2013) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badro J., Côté A. S. & Brodholt J. P. A seismologically consistent compositional model of Earth's core. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7542–7545 (2014) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziewonski A. M. & Anderson D. L. Preliminary reference Earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 25, 297–356 (1981) . [Google Scholar]

- Wood B. J., Walter M. J. & Wade J. Accretion of the Earth and segregation of its core. Nature 441, 825–833 (2006) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubie D. C. et al. Heterogeneous accretion, composition and core–mantle differentiation of the Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 301, 31–42 (2011) . [Google Scholar]

- Wood B. J. Carbon in the core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 117, 593–607 (1993) . [Google Scholar]

- Litasov K. D. et al. Thermal equation of state and thermodynamic properties of iron carbide Fe3C to 31 GPa and 1473 K. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 5274–5284 (2013) . [Google Scholar]

- Akahama Y. & Kawamura H. Pressure calibration of diamond anvil Raman gauge to 310 GPa. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 043516 (2006) . [Google Scholar]

- Baron A. Q. R. et al. An X-ray scattering beamline for studying dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 61, 461–465 (2000) . [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa D., Uchiyama H., Tsutsui S., Fukui H. & Baron A. Q. R. Compound focusing for hard x-ray inelastic scattering. Proc. SPIE 8848–88480F (2013) . [Google Scholar]

- Fukui H. et al. A compact system for generating extreme pressures and temperatures: an application of laser-heated diamond anvil cell to inelastic X-ray scattering. Rev. Sci. Instrum 84, 113902 (2013) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fåk B. & Dorner B. Phonon line shapes and excitation energies. Phys. B Condens. Matter 234-236, 1107–1108 (1997) . [Google Scholar]

- Scopigno T., Ruocco G. & Sette F. Microscopic dynamics in liquid metals: the experimental point of view. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 881–933 (2005) . [Google Scholar]

- Fiquet G. et al. Application of inelastic X-ray scattering to the measurements of acoustic wave velocities in geophysical materials at very high pressure. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 143, 5–18 (2004) . [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa S., Inui M., Matsuda K., Ishikawa D. & Baron A. Damping of the collective modes in liquid Fe. Phys. Rev. B 77, 174203 (2008) . [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. et al. Melting behavior of Fe-O-S at high pressure: a discussion on the melting depression induced by O and S. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B05207 (2010) . [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A. et al. In situ X-ray observation of iron using Kawai-type apparatus equipped with sintered diamond: absence of β phase up to 44 GPa and 2100 K. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1126 (2003) . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References