Abstract

Abstract

Objective

: To describe the use and reporting of Health Impact Assessment (HIA) in Australia and New Zealand between 2005 and 2009.

Methods

: We identified 115 HIAs undertaken in Australia and New Zealand between 2005 and 2009. We reviewed 55 HIAs meeting the study's inclusion criteria to identify characteristics and appraise the quality of the reports.

Results

: Of the 55 HIAs, 31 were undertaken in Australia and 24 in New Zealand. The HIAs were undertaken on plans (31), projects (12), programs (6) and policies (6). Compared to Australia, a higher proportion of New Zealand HIAs were on policies and plans and were rapid assessments done voluntarily to support decision-making. In both countries, most HIAs were on land use planning proposals. Overall, 65% of HIA reports were judged to be adequate.

Conclusion

: This study is the first attempt to empirically investigate the nature of the broad range of HIAs done in Australia and New Zealand and has highlighted the emergence of HIA as a growing area of public health practice. It identifies areas where current practice could be improved and provides a baseline against which future HIA developments can be assessed.

Implications:

There is evidence that HIA is becoming a part of public health practice in Australia and New Zealand across a wide range of policies, plans and projects. The assessment of quality of reports allows the development of practical suggestions on ways current practice may be improved. The growth of HIA will depend on ongoing organisation and workforce development in both countries.

Keywords: Health Impact Assessment, Australia, New Zealand, audit

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for the implications for health and the distribution of health impacts to be routinely considered in policy making and practice, through collaborative action by the health sector and non-health sector actors.1–5 While the need to address this has been understood for a long time, efforts by the health sector to work effectively with other sectors to influence their planning and policy development have been constrained, in part, by the lack of assessment tools and mechanisms to assess and negotiate recommended actions.5–8 Health Impact Assessment (HIA) has been identified as one of a limited number of methods that are available to address the social and environmental determinants of health prior to implementation of proposed policies, plans or projects designed to maximise future health benefits and minimise risks to health.1,9,10

The use of HIA in conjunction with Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) processes has been adopted by a wide range of international agencies and groups, including the International Finance Corporation11,12 and the private sector as part of the Equator Principles – a financial industry agreement that sets out benchmarks for major project lending – and the International Council on Mining and Metals.13 It has also been adopted by a number of banks in Australia and New Zealand (NZ).14 Despite these efforts, health considerations are infrequently included in EIA.15,16

HIA is also being promoted as a cornerstone of healthy public policy;17,18 for example, its use has been adapted as a health lens assessment as part of South Australia's Health in All Policies initiative.19,20 Australia and NZ have been early adopters in developing guidelines and advocating for incorporating health within statutory EIA processes with a strong focus on major projects.16,21–26

There are now a number of papers and reports that describe the development of HIA in Australia. Three major strands have been identified. The first of these were attempts to incorporate HIA into EIA commencing with an NHMRC report in 1994 that argued HIA should not be a separate assessment but incorporated into EIA. This was followed by the development of HIA guidelines in 2001; however, incorporating HIA in EIA continues to be an aspirational goal. The second strand sought to expand the use of HIA beyond projects to include HIA of government policies and plans. This approach took a broader social view of health and used a wider base of evidence to assess impacts. The third and most recent strand included a focus on the distribution of impacts (equity).

Despite Australia's earlier role as an international leader in the development of HIA, the level and intensity of HIA in Australia has fluctuated over time.27,28 HIA remains poorly integrated into policy development and decision-making in Australia and NZ and there is limited legislative support for its use. The reasons for this are complex and still poorly understood but are thought to include:29,30

the predictive nature of HIA and the fact that few HIAs are followed up to see if predictions eventuated, as well as the difficulty in determining if an impact was avoided due to the HIA;

frequent difficulties in identifying ‘evidence’ of size and certainty of impacts;

the lack of structures and procedures to allow the recommendations of HIAs to influence the policies, programs or projects of other sectors;

the reluctance to introduce another impact assessment process into an already crowded and contested space;

a lack of clarity about who should fund and conduct HIAs when government is the proponent;

the reality that each state and territory develops their own approach to HIA in response to contextual and historical conditions;

the lack of a robust research base that describes current practice, the effectiveness of HIA and factors affecting effectiveness; and

difficulty in siting or locating responsibility for undertaking HIA inside government.

In New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria, state health departments funded capacity building projects to strengthen local capacity to undertake HIA. In South Australia, a health lens is being used in a similar way to HIA. In Victoria, the focus of their capacity building program was on Local Government and in NSW the focus was on health system capacity.31,32

The NZ Public Health Advisory Committee built capacity by developing a toolkit supported by an extensive training program, a program to fund evaluations and various other activities, as well as the ‘Learning by Doing’ program, to promote HIA activity. These measures did not result in the NZ Government broadly adopting HIA nationally, and has had relatively limited penetration into local authority planning activities, especially the resource consent process. Australian and NZ capacity programs have now been defunded (NSW in 2008, NZ in 2010).

There continues to be an interest by public health policy makers and other stakeholders in the use of HIA. However, the lack of detailed knowledge of the potential use of HIA is often opinion-based and not informed by research or practice. For example, the recent Australian Community Affairs Reference Committee response to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health report noted that:

Although the Department [Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing] conceded that HIA might be a useful tool we believe that they have the potential to be expensive and time consuming, and we believe that this needs to be taken into account in any further considerations of these.(4.55).

There is an important gap in our current knowledge of how HIA is being used, by whom and for what in Australia and NZ. It is also unclear if the HIA reports are adequate to confidently influence policy and decision-making.

The purpose of this paper is to provide an empirical basis for discussion of the use of HIA in Australia and NZ by describing the characteristics of HIAs undertaken. The paper also trials the use of a review package to assess the quality of the HIA reports (not the HIAs themselves).

Methods

Identification and selection of HIAs

Several methods were used to identify all Australian and NZ HIAs conducted during the period 2005–2009. HIAs conducted or supported by the authors were included (n=16). Next, HIAs were identified by searching established websites in the region (primarily HIA Connect in Australia and the NZ Ministry of Health website) and Google (including Google Scholar) searches for published reports (n=6) and grey literature. We searched APAIS but there were no relevant returns. Assistance was also sought from existing HIA and health equity networks and contacts in other states and territories in Australia and NZ to recruit and identify HIAs for the study. Finally, email lists, Twitter and blog posts (such as the IAIA HIA Blog and Croakey) were also used to request HIAs and publicise the study.35

HIAs were included in this study if they were prospective, had an available HIA report, contained a discrete health component in the assessment, contained clear recommendations and the investigators could identify a defined contact point or person. HIAs were assessed by two of the investigators to resolve questions about inclusion.

Description of the characteristics of HIAs

The characteristics of the HIAs were obtained from the HIA reports, including: year and country in which the HIA was conducted; whether it was conducted on a policy, plan or project; the focus; health impacts assessed; level; organisations involved; and whether it was undertaken as part of a capacity building project.

Box 1: Definitions.

Health Impact Assessment

HIA is intended to produce a set of evidence-based recommendations to inform decision-making. HIA seeks to maximise the positive health impacts and minimise the negative health impacts of proposed policies, programs or projects.

The procedures of HIA are similar to those used in other forms of impact assessment, such as environmental impact assessment or social impact assessment. HIA is usually described as following the steps listed, although many practitioners break these into sub-steps or label them differently:33

Screening – determining if an HIA is warranted/required.

Scoping – determining which impacts will be considered and the plan for the HIA.

Identification and assessment of impacts – determining the magnitude, nature, extent and likelihood of potential health impacts, using a variety of different methods and types of information.

Decision-making and recommendations – making explicit the trade-offs to be made in decision-making and formulating evidence-informed recommendations.

Evaluation, monitoring and follow-up – process and impact evaluation of the HIA and the monitoring and management of health impacts.

Health Risk Assessment

Health risk assessments are a key component of the overall assessment and management of health impacts from development within a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) framework. The health sector in Western Australia applies health risk assessments to evaluate the potential impacts on public health from activities through a structured evaluation of the scientific, technical and social components of risks. The health risk assessment process is usually based on ensuring that the risks to health can be mitigated by the activity meeting appropriate health criteria or standards.34

Levels of HIA

There are three levels at which HIAs are generally undertaken, depending on available time and resources:33

Desk-based HIA, which takes 2–6 weeks for one assessor to complete and provides a broad overview of potential health impacts;

Rapid HIA, which takes approximately 12 weeks for one assessor to complete and provides more detailed information on potential health impacts; and

Comprehensive HIA, which takes approximately 6 months for one assessor and provides an in-depth assessment of potential health impacts.

Quality assessment of HIA reports

The HIA Reports were then appraised using the Review Package for Health Impact Assessments Reports of Development Projects to determine the quality of the HIA reports.36 This was done as the HIA report is often the only formal documentation of the process and findings, and it frequently forms the main basis by which policy and other decision-makers decide on whether the recommendations should be acted upon. Review packages are an emerging approach in HIA and tools to undertake this task are still under development, though review packages have been used in other forms of impact assessment for some time.37 To our knowledge, this is the first time such an assessment has been reported in the peer-reviewed literature. The review package was initially based on an existing review tool for Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and the modified form for use with HIA reports. The draft review package was presented and discussed at national and international conferences, and reviewed by an expert panel.36

The review package covers four domains: context, assessment, management and reporting (see Box 2). Each of these domains includes nine review questions (or criteria) that require the reviewer to provide a grading between A and D (highest to lowest quality grading) in response to the review questions. The domain results are used to decide on an overall grade based on a subjective overall assessment by the reviewer. An initial assessment of six HIA reports was undertaken by all investigators to gain agreement about the grading approach and the use of the Review Checklist. The remaining reports were reviewed by two reviewers, with a 20% sample being reviewed by a third. Grading was based on consensus between the reviewers. There was broad agreement between reviewers on the overall grading of HIAs domains contained within the review package, even though there was some variation in the scoring of specific checklists items. Differences were resolved by discussion.

In use, the authors felt the review package scoring needed a more graduated or granular approach. We addressed this by including a plus and minus ranking to each grading to make the grading more graduated, and explicitly acknowledging that these assessments were subjective.

Box 2: Review package summary of key features.

Outline of review package

-

1. Context

1.1 Site description

1.2 Description of project

1.3 Public health profile

-

2. Management

2.1 Identification and prediction of potential health impacts

2.2 Governance

2.3 Engagement

-

3. Assessment

3.1 Description of health effects

3.2 Risk Assessment

3.3 Analysis of distribution of effects

-

4.Reporting

4.1 Discussion of results

4.2 Recommendations

4.3 Communication and layout

Summary of grading

A: Relevant tasks well performed, no important tasks left incomplete, only minor omissions or inadequacies.

B: Can be considered satisfactory despite omissions and/or inadequacies.

C: Parts well attempted but must, as a whole, be considered unsatisfactory because of omissions or inadequacies.

D: Not satisfactory, significant omissions or inadequacies, some important task(s) poorly done or not attempted.

Results

Identification of HIAs

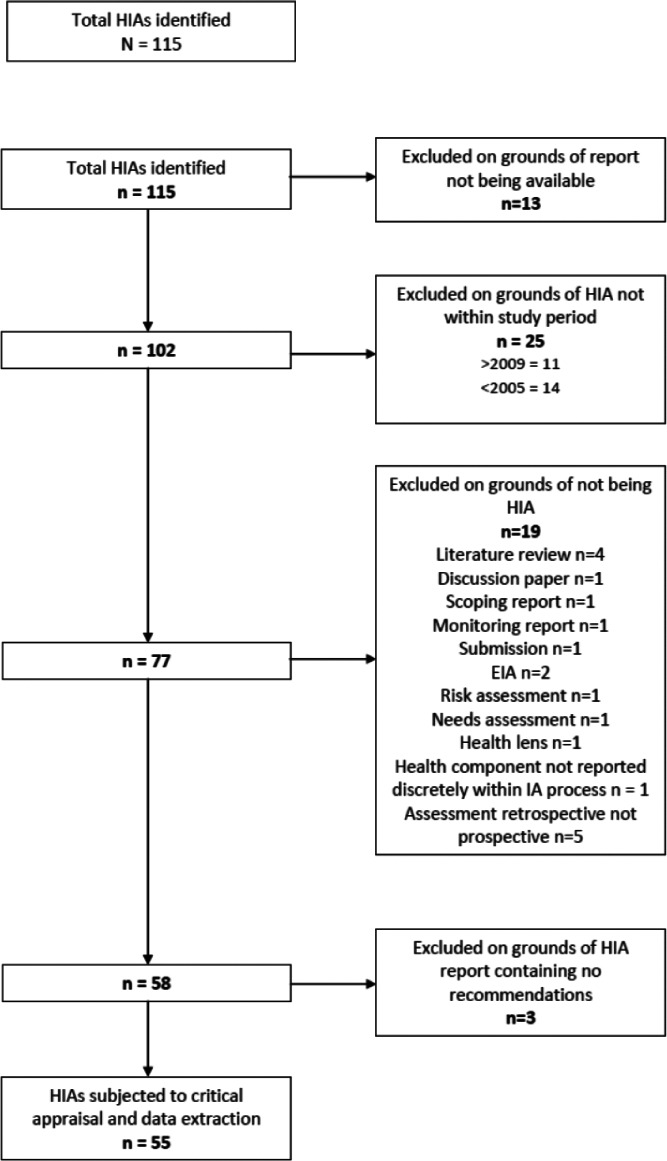

A total of 115 potentially eligible HIAs were identified; of these 55 met the inclusion criteria (See Figure 1). Reasons for exclusion were:

Figure 1.

Inclusion Diagram.

19 were evaluations of a health intervention rather than a prospective HIA

3 had no recommendations

13 had no reports available

25 were not conducted in the study period.

Characteristics of the HIAs

Tables1 and 2 provide an overview of the HIAs in the study. Thirty-one of the 55 identified HIAs included in the study were undertaken in Australia and 24 in NZ. The majority of HIAs were undertaken on plans (31), with fewer on projects (12), programs (6) and policies (6). There were differences between Australia and NZ, with more focus on policy and plans in NZ and a stronger focus in Australia on project level HIAs. In Australia, more HIAs were undertaken outside capacity building projects (that is, without direct government HIA Capacity Building Support) than in NZ. All HIAs in NZ could be classified as decision-support HIAs. In Australia, although the majority were decision-support HIAs, there were also mandated HIAs (4), Advocacy HIAs (2) and one community-led HIA (see Box 3). The majority of HIAs in both countries were undertaken on land use planning. More Australian HIAs were undertaken on health service policies (26%) and plans (8%). More than half of HIAs conducted in NZ were rapid compared to a third in Australia. There were no comprehensive HIAs reported from NZ in the study period. The number of HIAs completed over the study period varied per year (2005 n=2; 2006 n=14; 2007 n=10; 2008 n=18; 2009 n=11).

Table 1.

Australian Health Impact Assessments 2005–2009 (refer to HIA Blog for copies of reports45).

| Year | State | Name of HIA | Description | Capacity building project | Policy, Plan, Programme, Project | Depth | Topic | Impacts Assessed | Stakeholders involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | QLD | EFHIA of alternative patterns of development of the Whitsunday Hinterland and Mackay Regional Report | Area plan to influence land-use planning | No | Plan-options | Rapid | Land use | Safety, injury, crime, physical activity, physical access, social cohesion | Local government, health service, state planning agency |

| 2009 | NSW | EFHIA of the review of Goodooga Health Service | Health service implementation plan to reduce services in a small rural community | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Health service | Access to health services – emergency medical services, visiting health services, staffing and facilities, service models | Local community, health service, university |

| 2008 | SA | EFHIA South Australian Australian Better Health Initiative School and community Initiatives | Implementation of a State-wide school and community initiative | No | Program | Intermediate | Health service | Service delivery and access, healthy weight and obesity, early child development | Health service, university, other agencies in an advisory role |

| 2008 | QLD | HIA Flinders Street Redevelopment Project | Program to look at redevelopment of a CBD main street | No | Project | Rapid | Land use | Safety, security, community Identity, social participation, walkability and urban form, environmental sustainability | Local government, health service |

| 2008 | NSW | Good for Kids good for life EFHIA | Implementation of a State-wide school and community initiative | Yes | Program | Rapid | Health service | Service delivery and access, childhood obesity, nutrition, physical activity | Health service, Aboriginal community controlled organisations, education department |

| 2008 | NSW | HIA Lithgow City Council Strategic Plan | Plan to implement land-use strategic plan from local government | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Urban form, walkability, food access, social participation, waste and contamination | Local government, health service |

| 2008 | VIC | Leopold Strategic Footpath Network HIA | Plan to implement a strategic footpath network in CBD | No | Project | Intermediate | Land use | Accessibility, active transport, urban form and the built environment, obesity, physical activity, walkability | Local government, university, health service |

| 2008 | NSW | Oran Park and Turner Road HIA | Land-use plan aimed for an area | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Active transport, social connectivity, physical activity, injury, food access. | Local government, health service, state planning authority |

| 2008 | VIC | A matter of equity – Case Study Frankston City Council | Land-use plan aimed for an area | No | Program | Rapid | Food | Food access and quality | Local government, university |

| 2008 | VIC | SHIA of Dandenong High School Doveton Campus Closure | Plan to close a school and amalgation of students into other area schools | No | Project | Intermediate | Education | Service delivery, social participation, | Education department, an interagency neighbourhood renewal group, local government, university, health service |

| 2008 | NSW | SIA Potts Hill | Plan to redevelop an area | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Land use | Employment, community infrastructure, open space and recreation, housing, transport, safety, communication | Land use statutory authority, local government, private sector, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2008 | WA | Health Impacts of Climate Change Adaptation Strategies for WA | Plan of scenarios and state-wide strategies to adapt to climate change | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Climate change | Extreme events, temperature, water quality, water-borne disease, vector-borne disease, air quality, food-borne disease, nutrition, lifestyle | State health department, planning department, university, other agencies in advisory roles |

| 2007 | VIC | HIA Hobson Bay Urban Greywater Diversion Project | Land-use plan for an area | No | Plan-options | Rapid | Water | Water quality, water-borne disease, vector-borne disease, contamination, stigma, green space, chemical exposure | Local government |

| 2007 | NSW | HIA Coffs Harbour Our Living City Settlement Strategy | Land-use plan for an area | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Walkability, urban form, safety, crime, physical activity and cycling, public transport, community involvement | Local government, health service |

| 2007 | NSW | Greater Western Sydney Urban Development HIA | Land-use plan for a regional area | Yes | Policy | Intermediate | Land use | Transport, urban form, green space, economic activity, social services and infrastructure, air quality, regional climate, physical activity, food access, employment, accident and injury, access to services, social connectedness | Regional organisation of local government councils, local government, health service, university, planning department, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2007 | NSW | HIA of Redevelopment of Liverpool Hospital | Project to redevelop a hospital | Yes | Project | Intermediate | Health service | Service delivery, asbestos exposure, accessibility, injury, safety, building design, urban form | Health service |

| 2007 | WA | HIA of Landfill Site and Housing Development in Mundijong WA | Plan to introduce a landfill site and housing development | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Exposure to toxins, air quality, noise, fire risk, odour, dust, vector bourne disease | Local government, state planning agencies, university |

| 2007 | NSW | HIA of Carpark Waste Encapsulation remediation | Plan to implement waste remediation for a car park | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Waste Management | Exposure to health hazards and toxins, site contamination | Local government, private sector, state planning authorities |

| 2007 | QLD | SIA of Gatton Correctional facility | Plan to implement a correctional facility | Yes | Plan-options | Comprehensive | Institution | Workforce and employment, safety/security, visitors, release/parole arrangements, prisoner health services, community interaction | Department of communities, local government, state planning department, |

| 2007 | NSW | HIA on Rural Health Service Redesign Proposal | Plan to redesign a rural health service | Yes | Plan-options | Comprehensive | Health service | Service delivery, service quality, access and availability, workforce, costs | Health service, local government, local community |

| 2007 | NSW | Bonnyrigg Living Communities SIA | Land-use and regeneration for an area | No | Project | Comprehensive | Housing | Safety, social integration, community capacity and wellbeing, amenity and access, housing | State housing department, local government, health service, Premier's Council for Active Living |

| 2006 | NSW | HIA of Greater Granville Regeneration Strategy | Land-use and regeneration for an area | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Land use | Transport, traffic, safety and injury, business and economic activity, community services, urban form, green space, housing | Local government, state housing department, health service, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2006 | NSW | HIA of Indigenous Environmental Health Workers | Plan to introduce an Indigenous Environmental Health Worker | Yes | Plan-options | Intermediate | Environmental health service | Service delivery, workforce, employment, training, community ownership and self-determination | Health service, local government, Aboriginal community controlled organisations |

| 2006 | NSW | Rapid Equity Focused HIA of the Australian Better Health Initiative: Assessing the NSW components of priorities 1 and 3 | Health program to be implemented across a state | No | Program | Intermediate | Health service | Urban form, service delivery, early child development, physical activity, nutrition, information services | State health department, university, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2006 | NSW | Wollongong Foreshore Precinct Plan | Land-use plan for an area | Yes | Plan-options | Desktop | Land use | Urban form, injury, sun protection, safety and crime, physical activity, nutrition and access to food, social participation | Local government, health service, university |

| 2006 | NSW | Bungendore HIA: urban development in a rural setting | Land-use plan for an area | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Land use | Physical activity, water for domestic, recreational and industrial uses, social cohesion (“neighbourliness”) | Local government, health service, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2006 | NSW | SIA of Lower Hunter Regional Strategy | Land-use plan for a regional area | Yes | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Social infrastructure, service delivery, urban renewal, mixed land use, employment, transport | Health service, state planning department, a regional coordinating group of state agencies |

| 2006 | VIC | HIA in the East Gippsland Shire Council 5 year arts and culture strategic plan | Art and cultural program implemented for local government | Yes | Program | Desktop | Community Service | Service delivery, community participation, social inclusion, mental health | Local government, university |

| 2006 | VIC | HIA in the East Gippsland Shire Council Kerbside waste collection strategy | Plan to implement a waste management plan | Yes | Program | Rapid | Waste Management | Waste management, mental health, contamination, cost and savings, environmental sustainability | Local government, university |

| 2006 | NSW | HIA on an Integrated disease prevention campaign | Plan to implement an integrated disease prevention campaign | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Health service | Service delivery, behaviour change, social marketing | State health department, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2005 | QLD | HSIA of South East Queensland Regional Plan | Prospective population state-wide strategies | No | Plan-options | Comprehensive | Land use | Urban form, transport, social infrastructure, lifestyle and behaviour, green space | State health department, state planning department, other agencies in advisory capacity |

Table 2.

New Zealand Health Impact Assessments 2005–2009 (refer to HIA Blog for copies of reports45).

| Year | Name of HIA | Description | Capacity building project | Policy, Plan, Programme, Project | Depth | Topic | Impacts Assessed | Stakeholders involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Whakawateatia Hawke's Bay District Health Board: HIA on the proposed Air Quality Plan Change | Plan to change air quality standards | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Air | Air quality, particulates, temperature, indoor air quality, costs, | Health service, regional government |

| 2009 | Wairarapa Non-fluoridation of water WOHIA | Plan to implement a water fluoridation plant to supply two local governments | Yes | Plan-options | Desktop | Water | Oral health, water supply, water quality, community conflict | Health service, local government |

| 2009 | HIA of Makoura Responsibility Model | Project aimed to encourage self-responsibility and self-management in students to deal with challenging behaviour | Yes | Project | Rapid | Education | Service delivery, relationships and whānau (extended family and community) | Education ministry, health service, students and families |

| 2009 | HIA on the draft Wairoa District Council Waste Management Activity Management Plan | Plan to implement a waste management plan | Yes | Plan-options | Desktop | Waste Management | Waste management, cost, social connectedness, vector-borne disease, employment | Local government, health service |

| 2009 | HIA on Flaxmere Town Centre Urban Design Framework Proposal | Area plan to influence land-use planning | Yes | Plan-options | Desktop | Land use | Urban form, physical activity, social participation, crime, active transport | Local government, health service, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2009 | HIA Implementation of Oral Health Strategy Location of a Community Clinic in Flaxmere | Project aimed to implement oral health strategy | Yes | Project | Intermediate | Health service | Service delivery – access and availability, oral health, | Health service |

| 2009 | Age-Friendly Community shaping the Future for Waihi beach | Plan to inform the future land-use of a beachside community | Yes | Plan-options | Intermediate | Community Service | Housing, transport, social participation, outdoor spaces/urban form, employment, community health and support services | Local government, health service |

| 2009 | Auckland Regional Land and Transport Strategy HIA | Project to implement a regional land transport strategy | No | Policy | Comprehensive | Transportation | active transport, liveability, safety, housing, social participation, healthy lifestyles | Regional government, local government, health service, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2009 | Manukau Built Form and Spatial Structure Plan HIA Report | Land-use plan for an area | Yes | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Active transport, liveability and vitality, safety, housing, kaitiakitanga (guardianship of the environment) | Local government, health service, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2008 | HIA Central Plains Water Scheme | Proposed irrigation scheme for 60,000 Ha of land | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Water | Water quality and contamination, water bourne disease, flooding, cultural and spiritual impacts for Māori | Health service (informed regulatory process without direct involvement of other stakeholders) |

| 2008 | HIA of Regional Policy Statement Regional Form and Energy Draft Provisions | Policy implemented on regional land use and energy provision | No | Policy | Rapid | Land use | Heating, housing, cost | Energy ministry, health service |

| 2008 | Ranui Urban Concept Plan HIA | Land-use plan for an area | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Housing and housing density, green space, urban form, social connectedness, transport, cost and affordability | Local government, health service |

| 2008 | HIA McLennan Housing Development | Plan to implement housing development types | No | Plan-options | Rapid | Housing | Social infrastructure, walkability, community cohesion | Local government, health service, private sector |

| 2008 | Proposed Liquor Restriction Extensions in North Dunedin HIA | Plan to implement liquor restrictions in student neighbourhood | Yes | Policy | Intermediate | Harm minimisation | Alcohol access and supply, crime, perception of safety, injury, waste management, mental health | Local government, health service, university |

| 2008 | Tokoroa Warm Homes Clean Air Project Health and Well-being Impact Assessment | Plan to change air quality standards | No | Plan- options | Rapid | Air | Air quality, economic activity, social participation, particulate exposure, housing, heating | Health service, regional government |

| 2008 | HIA on Draft Hastings district Council Graffiti Vandalism Strategy | Program to implement graffiti strategies | Yes | Plan- options | Rapid | Community Service | Social participation, perception of safety, public space, visual amenity | Local government, health service |

| 2007 | Kerikeri-Waipapa Draft Structure Plan | Land-use plan for an area | No | Plan- options | Intermediate | Land use | Housing and housing density, transport, urban form | Local government, health service |

| 2006 | Wairau Road Widening HIA | Project to expand a suburban road works | No | Project | Rapid | Transportation | Transport, safety, injury, air quality, housing | Ministry for the Environment, project consultants, health service, small business |

| 2006 | HIA of Greater Wellington Regional Land Transport Strategy | Policy implemented on regional land use | No | Policy | Rapid | Transportation | Transport, transport affordability, active transport | Regional government, health service |

| 2006 | HIA Healthy Wealthy and Wise Future Currents Electricity Scenarios 2005–2050 | Plan to implement new energy saving provisions | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Energy | Economic impacts and employment, cost, housing, urban form and design, heating, sense of place, service delivery and access | Parliamentary commissioner for the environment's office, health service |

| 2006 | HIA Greater Christchurch Urban Development Strategy options | Land-use plan aimed for an area | No | Plan-options | Intermediate | Land use | Water quality, air quality, waste management, social connectedness, housing, transport | Local government, regional government, health service, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2006 | SIA of the Draft Nelson City Council Gambling Policy | Implementation of a gambling policy | No | Policy | Rapid | Harm minimisation | Gambling, siting options | Local government, health service, other agencies in advisory capacity |

| 2006 | HIA of Mangere Growth Centre Plan | Plan to manage growth | No | Plan-options | Rapid | Land use | Urban form, economic activity, social cohesion, housing, safety, transport, physical activity | Local government, health service |

| 2005 | Avondale's Future Framework Rapid HIA | Land-use plan for an area | Yes | Plan-options | Rapid | Land use | Transport, social cohesion, open space/urban form, housing, waste, education, waterways/environment, employment | Local government, health service, housing ministry, education agencies, other agencies in advisory capacity |

Box 3: Typology of HIA.38

Mandated

Carried out to fulfill a mandatory or regulatory requirement.

Decision Support

Usually undertaken voluntarily by, or in partnership with, the organisation responsible for developing the policy, program or project that is being assessed.

Advocacy

Undertaken by organisations and groups who are neither proponents nor decision-makers with the goal of influencing decision-making and implementation.

Community led

Conducted by communities to help define or understand issues and contribute to decision-making that has a direct impact on their health.

Assessment of the quality of the HIAs

Reports were graded A (n=1); B+, B, or B− (n=25); C+ (n=10); and C or C− (n=19). Overall, 47% of HIAs were graded as A or B and 65% of HIAs received C+ or higher. There were no HIA reports judged to be unsatisfactory (D).

Findings from each domain are included as they provide useful guidance on how HIA reporting and process could be improved.

Context

Most HIAs described the relationship between the funding source and those who commissioned the HIA (47/55; 85%). The relationship between the proposal and other proposals, plans or policies occurring at the same time that could influence the HIA were reported as well. In addition, the links between the proposal and relevant policies underlying the HIA proposal and the significant partnerships needed between different sectors for the implementation of HIA findings were reported.

The HIA reports described the aims and objectives of the proposal well. All HIAs included either local census data or public health profiles to assess potential impacts on local communities (67%; 37/55 included public health profiles). These data were generally included in appendices and included mapping of local community characteristics.

Management

Most HIAs (76%; 42/55) were guided and scrutinised by a steering committee with members identified and terms of reference included (see Box 5). Thirty-eight (69%) described a process for developing a common understanding of the scope of the HIA among stakeholders. Most HIAs noted constraints of time and resources and often included a limitations section or detailed them in the discussion section as issues to be considered in undertaking future HIAs (75%; 41/55). Most HIAs listed the core groups involved but did not explicitly specify an engagement strategy for how stakeholder groups were identified and included. The nature of stakeholder involvement and proactive engagement of vulnerable disadvantaged groups was also poorly covered in many HIAs (see Box 4 for an example of stakeholder engagement).

Assessment

At the point of screening and scoping, all 55 HIA reports relied to some extent on qualitative data to identify impacts. This was often based on the perceptions of people who live and work in the area, expert opinion and extrapolations from other empirical research.

Only five HIA reports (9%) attempted to quantify health impacts. For example, the Regional Land Transport Strategy HIA (2009) conducted in NZ used health impact modelling to assess the impacts of the different strategic options for the year 2041 focusing on travel choices, emissions and safety options. There were some good examples of the use of civic intelligence. For example, in the Flaxmere Oral Health Strategy HIA, information from community stakeholders provided new evidence about the un-anticipated impacts of locating a community clinic within a school environment compared to a village centre.39

Most HIAs described and assessed potential health effects and presented these in a systematic way (52/55; 95%). Little attention was paid to the temporal impacts of the proposal and how impacts may change during different phases of development, implementation and wind-down phases of the proposal. Causal pathways for impacts were rarely presented. Most HIAs did not include assessments of the severity, intensity, reversibility, magnitude or importance of the impacts. For example, Table3 provides an excerpt from the Greater Granville Regeneration strategy HIA (2006) which shows the general nature of many assessments.

Table 3.

Excerpt from Table in Greater Granville Regeneration Strategy HIA.

| Main HIA Themes | Likelihood of Health Impact | Relative Size and Type of Health Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Transport, traffic, parking, pedestrian and cycle | Definite positive impact and probable negative impact | Large positive impacts if transport services and pedestrian connectivity are improved. |

| Large negative impacts if there is decreased access to transport services and reduced pedestrian connectivity. |

A total of 41 HIA reports (74%) mentioned issues of equity, and 46 (84%) contained recommendations targeting differential impacts on population groups. However, differential impacts on vulnerable and disadvantaged groups were poorly dealt with in the assessment phase. In part, this was because groups with the potential to experience differential impacts were often identified in the report but these differential impacts were rarely discussed in the assessment of health impacts, which tended to remain generalised. Further to this, most HIA reports did not make a clear link between the community profile and the final assessment of potential impacts.

Box 4: Example: Stakeholder Engagement in Central Plains Water Scheme HIA (2008).

This HIA reported that stakeholders in the workshops comprised topic experts and people who were knowledgeable about the local community and/or the population groups of interest. Participants included both supporters and antagonists of the Central Plains Water Scheme. The HIA report also listed the Māori groups involved and Māori participants at the HIA workshops in the appendix section.

Reporting

A list of recommendations was included in all of the reports and summarised in an Executive Summary. However, the differing perspectives of various stakeholders in arriving at recommendations were infrequently reported. Reporting of differing options and alternatives to the proposal varied. The extent to which impacts were potentially modifiable was rarely addressed in the reports.

Communication and layout

Most HIAs presented a well-structured report (87%; 48/55), usually in a high quality format. Little information was available on whether additional communications had been created for specific audiences, such as press releases or a short summary designed for high level decision-makers.

Box 5: Example of HIA placed in the Policy Context: Greater Western Sydney Strategy HIA (2007).

This HIA explores the potential impacts on population health and wellbeing of planned population growth and urban development in Greater Western Sydney over the coming 25 years. The HIA assesses major health determinants covered in the Sydney Metropolitan Strategy (2005), such as: physical activity; social connectedness; access to healthy food; air quality and local climate; accidents and injury; employment; and access to services and mobility. The HIA made explicit the relationship between it and relevant policies and also supported recommendations made in the NSW State Plan and Growth Centres planning instruments. The sectors involved in the management of this HIA were from local government, the health sector and universities. The wider reference group included land developers, other government agencies (such as agriculture), non-government organisations and community groups.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations of the study

This is the first empirical audit of HIA activity in Australia and NZ and it fills a knowledge gap about the characteristics and scope of HIAs in Australia and NZ. It adds to a small number of international studies that attempt to systematically describe the use of HIAs in a country or region.40,41 This study provides a solid baseline of HIA activity and also illustrates the growth of the field. We provide some new information about the quality of HIAs, the adequacy of methods for reviewing HIAs and how HIAs have been used in Australia and NZ

There are a number of limitations to this study. Firstly, despite comprehensive efforts, there may be a number of HIAs that have not been identified. Some of these may be treated as internal confidential information and not made publically available, some may have been conducted rapidly in-house on a policy or program proposal and not formally written up, and some may have been small scale and not circulated beyond those directly involved. Also, HIAs that were not satisfactorily completed would not have been written up or made publically available.

As the field develops, it will be important to ensure that the quality of the HIAs and HIA reports produced is of an acceptable standard. We relied on a review package developed specifically for assessing project developments, although we then applied it to policies and programs. This meant that some of the grading criteria were not always relevant. This study was unable to assess the extent to which review packages for policies and programs would be substantially different, and in what ways.

In addition, the assessment of quality was very subjective and the level of detail required to make an assessment was often not included in the report. Differences emerged in the ranking of questions within the domains, often due to lack of detail on the characteristics at the various levels within the reports and the subjective nature of the assessment. EH and HNC also felt that the final score given to the HIA did not always reflect their own assessment of the overall quality of the HIA. For example, the point at which HIA were ranked as unsatisfactory (parts are well attempted but must, as a whole, be considered unsatisfactory because of omissions or inadequacies) was seen as needing a more graded approach. We addressed this by including a plus and minus ranking to each grading – again in recognition that these assessments were subjective and required a more subtle assessment.

We feel that the overall findings of the review assessments need to be cautiously interpreted. They are based on subjective assessments and, as the majority of assessments were undertaken by only one reviewer (HNC), there is the possibility of bias. Some issues are not subjective, for example, the use of quantitative data. Since we were unable to follow up, it was not clear if lack of inclusion was a deficit in the report rather than a deficit in the work undertaken. Despite this, some issues were raised that are consistent with recognised gaps in HIA, for example, reporting of equity impacts.

The study shows that HIA has been used across Australia and NZ on a wide range of policies, programs and projects, suggesting that HIA methods have been found to be useful within the health sector and with many partner agencies, including community groups. We found some differences in practice between NZ and Australia. All HIAs aim to influence or change decision-making; however, in contrast to mandatory, advocacy and community-led HIAs, decision-support HIAs are commissioned by the decision-makers to inform their own decision-making process. All the NZ HIAs were categorised as decision-support HIAs with a strong emphasis on policy or strategic assessment. In Australia, there has been a stronger focus on project HIAs and some limited examples of mandated (within Social Impact Assessment frameworks), advocacy and community-led HIAs. There were different patterns in the types and levels of HIA between Australia and NZ. It is not clear at this stage if this reflects the ongoing development of an emerging field of public health practice which involves testing different approaches and levels, or contextual differences between the countries

In terms of wider international relevance our findings are comparable to those of a similar study on the use of HIA undertaken in the US between 1999–2007, which identified 27 completed HIAs.40 Those 27 HIAs were similar to our 55 in terms of the types of policies and programs, and range of partner organisations. The lack of a robust, predictive evidence base for HIA has been reported as a major constraint to the use of HIA as compared to risk assessment processes by public health practitioners,42 although this is contested.43 As with the US study, our HIAs were predominantly based on expert judgement and extrapolation from empirical research, rather than predictive modelling. We did identify good examples of the use of local knowledge in HIA reports.

While there is still limited published literature on the effectiveness and experience of HIA, this is changing with growth in the number of clearing houses (e.g. HIA GATEWAY, HIA Blog)44,45 and investment in research programs.

This is the first study to systematically review the quality of HIA reporting. We found that a majority of HIA reports are adequate, to the extent that our assessment methods enabled us to judge. We found assessing the quality of HIA reports challenging, with the assessment of quality being very subjective and the level of detail required to make an assessment often not being included in the report. We also found that assessing the quality of HIA reports (as assessed by the review package) does not necessarily correspond with the quality or effectiveness of the HIA itself and a more robust review package needs to be developed.

It is also not clear to what extent an international assessment package that allowed cross-country comparisons is feasible or acceptable. Many HIA Guides have been developed and there seems to be little international interest in a single guide. There is now general agreement on the steps of HIA46 and the fact that it is a prospective assessment, and so the development of standards may be an evolving process. Despite several limitations to the use of the review package, especially its ranking system, we are able to draw useful findings that have been presented under each of the four domains. As described below, we were also able to identify ways in which HIA could be improved.

Implications for policy, practice and research

Despite the limitations of the review package, it highlighted a number of areas where existing reporting practice could be improved. These include:

The distributional and/or equity impacts have to be routinely reported if HIA is to be promoted as a mechanism for addressing equity implications of policies and programs, as has been suggested by the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health.

More attention needs to be given to how stakeholders and communities are engaged in the assessment process and how this is reported.

The limited use of quantitative data needs to be addressed by development of an evidence base and workforce competence in using data that have strong predictive power to quantify potential impacts, and by training people in the use of best available evidence. It would be helpful to explore ways in which traditional health risk assessment processes can be integrated into HIA and to build modelling capacity into HIA practitioner training and networks.

Practitioners need to face the challenges of gathering existing evidence and evidence synthesis of impacts, making these evidence summaries widely available through existing web-based resources such as the HIA Gateway and HIA Connect.

The development of greater understanding and presentation of causal pathways between the exposure and health outcomes would be helpful in strengthening HIAs.

Greater clarity in the reporting of the assessment stage is required. This includes the reporting of how the assessment was carried out (e.g. how the evidence was valued and assessed, and what limitations were associated with this) and also the clearer description of identified impacts.

Linkages between recommendations and impact assessment should be made more explicit. For example, Ross et al. documented the links between findings, recommendations and subsequent impacts in the Atlanta Beltline HIA.47

There is a need for a clear stakeholder involvement and communication strategies before HIA is commenced.

Our research has shown that using HIA reports as a basis for assessing quality or effectiveness of HIAs is limited by a lack of agreement about minimum standards and content for HIA reports, the audience-specific nature of reports and the fact that they can only report on HIA at one point in time. They generally cannot report what happened following the HIA. This suggests there should be more emphasis on longitudinal studies of the process and impacts of HIAs, which are supplemented by interviews with stakeholders and other documentary sources concerning the effectiveness of HIAs following the formal report period.

Conclusion

This study has highlighted the emergence of HIA as a growing area of public health practice in Australia and NZ. It has identified some areas where current practice could be improved. It has also provided a review of HIA practice in Australia and NZ that will provide a valuable baseline future developments can be assessed against. HIA capacity-building projects were implemented in both countries during our study period as a mechanism for supporting and establishing the use of HIA; however, this investment has not been sustained. The future development of HIA will depend on building on this knowledge and experience, in order to create sustainability in HIA practice.

References

- Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva (CHE): World Health Organization; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care – Now More than Ever. Geneva (CHE): World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Health Development. Megacities and Urban Health. Kobe (JPN): World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Office for Africa. Libreville Declaration on Health and Environment in Africa, Libreville, 29 August 2008. Brazzaville (COG): World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health, World Conference on Social Determinants of Health, Rio de Janeiro, 19–21 October 2011. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harris E. Working Together: Intersectoral Action for Health. Canberra (AUST): AGPS; 1995. , et al. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Crossing Sectors: Experiences in Intersectoral Action, Public Policy and Health. Ottawa (CAN): PHAC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Bangkok Charter on Health Promotion in a Globalized World. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel A, Dannenberg A, Frumkin H. Designing and Building Healthy Places for Children. Int J Environ Health. 2008;2:338–55. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Roxas B. Health Impact Assessment in the Asia Pacific. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2011;31(2):393–5. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation. Performance Standards on Social and Environmental Sustainability. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation. Introduction to Health Impact Assessment. Washington (DC): IFC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Mining and Metals. Good Practice Guidance on Health Impact Assessment. London (UK): ICMM; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Equator Principles. The Equator Principles: A Financial Industry Benchmark for Determining, Assessing and Managing Social and Environmental Risk in Project Financing. Washington (DC): Equator Principles Financial Institutions; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PJ. Human health and wellbeing in environmental impact assessment in New South Wales, Australia: Auditing health impacts within environmental assessments of major projects. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2009;29(5):310–8. , et al. [Google Scholar]

- Harris P, Spickett J. Health impact assessment in Australia: A review and directions for progress. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2011;31(4):425–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nilunger MannheimerL. Introducing Health Impact Assessment: An analysis of political and administrative intersectoral working methods. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(5):526–31. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl267. , et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signal L. Strengthening health, Wellbeing and Equity: Embedding Policy-Level HIA in New Zealand. Soc Policy J N Z. 2006;29:17–31. , et al. [Google Scholar]

- Health SA. Health in All Policies [Internet] Adelaide (AUST): State Government of South Australia; 2007. [cited 2009 Feb 9]. Available from: http://www.health.sa.gov.au/PEHS/health-in-all-policies.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I, Buckett K, editors. Implementing Health in All Policies: Adelaide 2010. Adelaide (AUST): South Australian Department of Health; 2010. , editors. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. National Framework for Environmental and Health Impact Assessment. Canberra (AUST): NHMRC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Commission. A Guide to Health Impact Assessment: Guidelines for Public Health Services and Resource Management Agencies and Consent Applicants. Wellington (NZ): New Zealand Ministry of Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney M, Morgan RK. Health Impact Assessment in Australia and New Zealand: An exploration of methodological concerns. Health Promot Educ. 2001;8:8–11. doi: 10.1177/102538230100800104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney M. Current Thinking and Issues in the Development of Health Impact Assessment in Australia. N S W Public Health Bull. 2002;13(7):167–9. doi: 10.1071/nb02068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney M, Durham G. Health Impact Assessment: A Tool for Policy Development in Australia. Melbourne (AUST): Deakin University, Health Impact Assessment Unit; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- enHealth. Health Impact Assessment Guidelines. Canberra (AUST): Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, National Public Health Partnership; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harris P, Spickett J. Health impact assessment in Australia: A review and directions for progress. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2010;31(4):425–32. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RK. Institutionalising Health Impact Assessment: The New Zealand experience. Impact Assess Proj Appraisal. 2008;26(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson H. Assessing the unintended health impacts of road transport policies and interventions: Translating research evidence for use in policy and practice. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-339. , et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulis G. HIA forecast: cloudy with sunny spells later [Letter] Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(5):436–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn086. ; discussion 436–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick J, Blau J. Health Impact Assessment in Victoria: A Suggested Approach. Melbourne (AUST): Monash University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Roxas B, Simpson S. Health Impact Assessment in New South Wales. N S W Public Health Bull. 2005;16(7–8):105–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. Health Impact Assessment: A Practical Guide. Sydney (AUST): University of New South Wales, Research Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity; 2007. , et al. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Health Risk Assessment (Scoping) Guidelines. Perth (AUST): State Government of Western Australia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet M. Crikey. HEALTH BLOG [Internet] Melbourne (AUST): Crikey; 2010. How are Health Impact Assessments Changing Policy? (and Some Story Ideas for Journalists with an Interest in Health…) . In: Nov 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fredsgaard MW, Cave B, Bond A. A Review Package for Health Impact Assessment Reports of Development Projects. Leeds (UK): Ben Cave Associates; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Colley R. Reviewing the Quality of Environmental Impact Statements. Manchester (UK): University of Manchester; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Roxas B, Harris E. Differing forms, differing purposes: A typology of health impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2011;31(4):396–403. [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder M, Apatu A. HIA: Implementation of Oral Health Strategy – Location of a Community Clinic in Flaxmere. Wellington (NZ): New Zealand Ministry of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dannenberg AL. Use of Health Impact Assessment in the U.S: 27 Case Studies, 1999–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):241–56. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.015. , et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismar M, editor. The Effectiveness of Health Impact Assessment: Scope and Limitations of Supporting Decision-making in Europe. Copenhagen (DNK): World Health Organization, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2007. , et al, editors. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson H. HIA forecast: cloudy with sunny spells later? Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(5):436–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulis G. Comments to “HIA forecast: cloudy with sunny spells later” and related comments by Kemm and Joffe. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(5):436–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network of Public Health Observatories. HIA Gateway [Internet] London (UK): Public Health England; 2013. [cited 2013]. Available from: http://www.apho.org.uk/default.aspx?RID=40141. [Google Scholar]

- International Association for Impact Assessment. HIA BLOG [Internet] Fargo (ND): IAIA; 2013. [cited 2013]. Available from: http://healthimpactassessment.blogspot.com.au/ [Google Scholar]

- Hebert KA. Health impact assessment: A comparison of 45 local, national, and international guidelines. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2012;34:74–82. , et al. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CL. Health Impact Assessment of the Atlanta BeltLine. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(3):203–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.019. , et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]