Abstract

Abstract

Objective:

Obesity is the single biggest public health threat to developed and developing economies. In concert with healthy public policy, multi-strategy, multi-level community-based initiatives appear promising in preventing obesity, with several countries trialling this approach. In Australia, multiple levels of government have funded and facilitated a range of community-based obesity prevention initiatives (CBI), heterogeneous in their funding, timing, target audience and structure. This paper aims to present a central repository of CBI operating in Australia during 2013, to facilitate knowledge exchange and shared opportunities for learning, and to guide professional development towards best practice for CBI practitioners.

Methods:

A comprehensive search of government, non-government and community websites was undertaken to identify CBI in Australia in 2013. This was supplemented with data drawn from available reports, personal communication and key informant interviews. The data was translated into an interactive map for use by preventive health practitioners and other parties.

Results:

We identified 259 CBI; with the majority (84%) having a dual focus on physical activity and healthy eating. Few initiatives, (n=37) adopted a four-pronged multi-strategy approach implementing policy, built environment, social marketing and/or partnership building.

Conclusion:

This comprehensive overview of Australian CBI has the potential to facilitate engagement and collaboration through knowledge exchange and information sharing amongst CBI practitioners, funders, communities and researchers.

Implications:

An enhanced understanding of current practice highlights areas of strengths and opportunities for improvement to maximise the impact of obesity prevention initiatives.

Keywords: obesity prevention, community-based, prevention

The prevalence of adult obesity continues to rise internationally.1 In 2011–12, 62.8% of Australian adults were classified as overweight (35.3%) or obese (27.5%); and 25.1% of children aged 2–17 were overweight (18.2%) or obese (6.9%).2 Data from the Global Burden of Disease study, released in 2014, indicates that poor diet, followed by overweight and obesity (high body mass index) are now the two leading risk factors contributing to burden of chronic disease in Australia.3

The prevention of obesity through population-level intervention holds great promise and the literature includes examples of community-based intervention trials.4–7 Recent systematic reviews indicate that community-based and community-wide approaches show potential to prevent obesity,8 particularly in school settings,9 and should encourage community engagement, participation and capacity building,4,10 policy, built environments and social marketing4,9 and whole of community change.11 Other core elements of successful community-based interventions have been identified as: a) implementation of multiple strategies; b) operation across multiple levels such as the socio-ecological model levels of individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and public policy; and c) development of community participation and ownership.10 Additional considerations might include: the ideal duration required for an initiative, methods to evaluate the impact on obesity prevalence long term, elements of best practice and identification of target populations.8,9,11,12

Community-based efforts to prevent obesity have been defined as “… a program of activities that occurred in the community, either at or through community settings or by engagement with existing community group(s), with objectives that could be expected to influence energy balance by promoting healthy eating and/or physical activity … excluding one-off events (e.g. a healthy eating fair), projects that focused solely on individual behaviour change (e.g. through educational counselling), higher level policy or ‘social marketing only’ programs and treatment or management oriented projects that worked solely with overweight or obese individuals.”13 For this discussion, community-based obesity prevention initiatives (CBI) include those with a focus on healthy eating and/or physical activity adopting a multi-strategy approach (policy, built environment, social marketing, partnership building), within multiple settings (e.g. health, education, community and commercial sectors such as community organisations, schools, workplaces or clinics) and across multiple (socio-ecological) levels, excluding one-off events and one-on-one educational sessions with individuals or small groups of individuals.

In 2008, the Australian Federal Government launched a major investment of $932.7 million, through the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (NPAPH), to address the rising prevalence of lifestyle-related chronic disease through communities, early childhood education and care environments, schools and workplaces, supported by national social marketing campaigns. Funding to the states/territories was provided through the Healthy Communities Initiative ($71.8 million; 2009–2014), Healthy Children's Initiative ($244.4 million; 2011–2018), and Healthy Workers' Initiative ($221.8 million; 2009–2018), with an agreed monitoring and reporting process to meet a set of population-level performance benchmarks. These benchmarks were to be assessed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Reform Council at two time points: June 2016 and December 2017.14 The Federal Government budget of 2014 announced the NPAPH will cease as of 30 June 2014, forecast to generate savings to the Federal Government of $367.9 million over four years.15 The future health cost burden related to decreased investment in prevention remains unclear.

Within states/territories this and other funding has provided opportunities to expand CBI through local and state governments and to direct funding grants to individual communities. Some states/territories have also shared strategies, such as social marketing campaigns and telephone counselling services to reduce duplication and costs.16,17

These layers of investment make it difficult to obtain a comprehensive picture of the current landscape of CBI in Australia. Recent research indicates that a common focus of these initiatives has been to increase healthy eating and physical activity through education and skill building;18 however, a more comprehensive understanding of CBI currently operating in Australia is needed. This overview aims to increase the awareness of the breadth of CBI activity, highlight the areas of commonality and scope, catalyse discussions and knowledge exchange between practitioners, communities, funders and researchers, and illustrate the national obesity funding investment within Australia.

Objective

This paper reports on a mapping project undertaken to identify CBI operating in Australia during 2013; to provide a searchable online resource to facilitate knowledge exchange and shared learning amongst CBI practitioners and researchers; and to guide professional development towards best practice for CBI practitioners.

Methods

A comprehensive web-based review of local, state, territory and national initiatives was undertaken between 25 March and 31 December 2013. A total of 189 sites were returned using the search terms ‘“community based obesity prevention” site:.org.au 2012.2013′ [returned 14 sites], ‘“community based obesity prevention” site:.gov.au 2012.2013′ [returned 50 sites], and ‘“community based obesity prevention” site:.edu.au 2012.2013′ [returned 125 sites]. These websites were systematically examined and recorded if they met the inclusion criteria: reported on an initiative that focused on healthy diet or physical activity. Further details of the strategies used were included where identified, (policy, built environment, social marketing, partnership building). Websites were excluded if they did not identify an initiative operating in 2013, or if the website reported on a once-off single event or projects focused solely on individual behaviour change through one-to-one educational sessions.

The most common finding was an initiative connected to the NPAPH, of which the Healthy Children, Healthy Workers and Healthy Communities initiatives met the definition of CBI. The location, scope and mandate of the NPAPH were therefore examined in detail, including relevant implementation plans.14 This was followed by individual searches of the websites of the 92 local government areas funded through the Healthy Communities Initiative.

Where information could not be sourced via websites, further information was gained via email contact, and three key informant interviews were conducted with key stakeholders from the Healthy Communities and Healthy Workers initiatives. Meetings with state or territory-based Departments of Health and The Australian National Preventive Health Agency (ANPHA) helped inform the background to this mapping work.

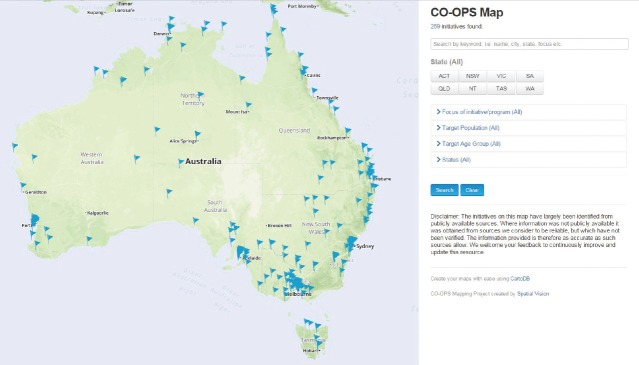

Geographic Information System (GIS) was used to integrate the data, Cartodb v.2.0 2012, and enable a searchable map interface for practitioners. This fully searchable map was made freely available on the CO-OPS website in October 2013 (www.co-ops.net.au/Pages/About/Map_of_Initiatives.aspx), see Figure 1. The map will be evaluated by monitoring the number of visits to the website, templates submitted to update the map, case studies submitted to augment featured CBI as well as the CO-OPS annual survey.

Figure 1.

The CO-OPS Map of CBI http://www.co-ops.net.au/map/index.html#/

Ethics approval for this project was obtained from Deakin University Human Ethics Advisory Group (HEAGH-127_2013).

Results

In total, 259 CBI were identified during the searching period. Table1 shows the breakdown between the focus of initiatives (healthy eating, physical activity, other) and the strategies used to address these foci. The four strategies chosen are drawn from literature as those with potential (when used as part of a multi-strategic, multi-level approach) to have an impact on obesity prevention long term (policy, partnership building, built environment, social marketing).6,9,19

Table 1.

Focus and strategies of community based obesity prevention initiatives.

| Count | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus of CBI | Healthy eating and physical activity (unspecified strategies) | 124 | 48 |

| Physical activity (unspecified) | 16 | 6 | |

| Healthy eating (unspecified) | 10 | 6 | |

| Other, e.g. tobacco control (unspecified) | 16 | 4 | |

| Specified Healthy Eating and Physical Activity strategies | 93 | 36 | |

| Four strategies | Social marketing + built environment + partnership building + policy | 37 | 14 |

| Three strategies | Built Environment + partnership building + policy | 9 | 3 |

| Social Marketing + partnership building + policy | 1 | 0 | |

| Built Environment + social marketing + policy | 0 | 0 | |

| Social Marketing + built environment + partnership building | 0 | 0 | |

| Two strategies | Policy + built environment | 5 | 2 |

| Policy + partnership building | 2 | 1 | |

| Social marketing + built environment | 1 | 0 | |

| Policy + social marketing | 1 | 0 | |

| Social marketing + partnership building | 0 | 0 | |

| Partnership building + built environment | 0 | 0 | |

| Single strategies | Policy | 15 | 6 |

| Built environment | 14 | 5 | |

| Social marketing | 7 | 3 | |

| Partnership building | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 259 | 100 | |

The majority (n=217 [84%]) had a joint physical activity and healthy eating focus. Less than half of the initiatives (n=93) identified the use of high-level strategies to affect obesity prevention longer term. Table1 outlines the combination of single and multiple strategies used by the CBI. Importantly, the initiatives that operated at a strategic level were most likely to combine all four strategies (n=37). Fewer initiatives combined three of these strategies with built environment, partnership building and policy being the preferred combination (n=9). A number of CBI also reported adopting the single strategies of policy (n=15), and changes to the built environment (n=14).

Table1 identifies various combinations of single and multiple strategies used to address the joint or single focus of healthy eating and physical activity to combat overweight and obesity.

An overview of the target populations shows that the majority of CBI targeted the adult population, namely 18 to <25 years (20%); 25 to <45 years (18%); and 45 to <65 years (17%) with 17% targeting under 18 years, with <5 years (7%) and 5 to <12 years (10%). The most frequently reported target population was Aboriginal people (42%), followed by low income populations (35%). Torres Strait Islander communities were specifically mentioned in 19% of CBI, while culturally and linguistically diverse populations (CALD) were least targeted (6%). Specific settings were not explored in this phase of the mapping activity, however, where a CBI self-identified a setting, these can be found through the free search field on the map. New South Wales (21%) and Victoria (20%) reported the greatest number of CBI with Tasmania (3%) and ACT (4%) reporting least activity, which is fairly consistent with population density in these states and territories.

The interactive map went live on 21 October 2013, and the website has recorded 626 visits in the first five months to March 2014. Engagement with the map has been enhanced further though the provision of an online case study template for practitioners to provide a narrative about their initiative which is appraised and attached to the map.

Discussion and Conclusions

The interactive map provides the first visual and searchable central repository of CBI activity across Australia. This national portrayal and macro-analysis of the obesity prevention landscape is further enhanced by reporting of the types and combinations of strategies employed in different geographical locations. This audit approach advances a conventional report of summary information, and provides a foundation upon which to explore, exploit and enrich the data over time and provide opportunities for future analysis. More detailed data regarding reach (population size distribution, geographic coverage, duration and capacity); characteristics (role of local and state-based organisations and government, target groups, settings and strategies; quality (best practice principles) and likelihood of effectiveness and sustainability of Australian CBI will be reported through a nation-wide survey currently in progress by CO-OPS.

The majority of initiatives on the map met the definition of CBI in terms of focusing on healthy eating and/or physical activity, however, a minority adopted a multi-strategy approach (policy, built environment, social marketing, partnership building), with implementation across multi settings and at multiple levels. The use of a multi-strategy, multi-level approach is consistent with the recommendations for population change and is consistent with evidence for prevention effectiveness.10

Statistics of current usage suggest that the interactive map provides practitioners, funders and researchers with a useful online resource to discover and examine CBI both locally and interstate. The map has the potential to facilitate knowledge exchange, new collaborations and information-sharing amongst CBI practitioners and researchers through direct access to information on the geographic location and basic characteristics of each CBI. The development of case study narratives based on best practice principles20 will contribute a more detailed description of individual initiatives being implemented. Appraisal of these case studies provides an opportunity for practitioners and program funders to receive feedback to guide future practice. Embedding case studies into the map of CBI further enhances information sharing.

It is relevant to mention that the new Commonwealth budget, announced in May 2014, proposes to defund the NPAPH initiative. This will impact significantly on state/territory evaluations in place to assess performance benchmarking and the national evaluation commissioned to provide insight into this funding approach which recognised the need for long-term funding (nine years) to achieve systemic population level change. The annual update of the interactive map will provide important information regarding the continuation of these CBI.

Strengths and limitations

Due to the reliance on websites for identification of initiatives, it is likely that initiatives without a clear web presence will not have been included. This limitation was partially addressed through the use of key informant interviews, meetings and workshops with stakeholders and personal communications with experts in the field of obesity prevention in Australia. A template is also provided on the website to enable CBI practitioners to add new or edit existing initiatives on the map.

The search criteria for data included on the map is not mutually exclusive, for example, a search to identify programs targeting children under 5 years of age will not exclude the program if the same program also targets school age children. In some instances this may appear to be double-counting.

The objective of the map was not to provide a detailed dataset for each CBI identified, therefore, it is limited in the depth of detail provided for each initiative. In its present format, the map provides a useful overview of current initiatives. Ongoing maintenance and development of the map is required to ensure up-to-date information and expansion to provide opportunities for future analysis regarding performance outcomes, cost-effectiveness and return on investment. A nationwide survey currently in progress by CO-OPS will report upon detailed characteristics, quality and likely effectiveness and sustainability of Australian initiatives.

Visits to the website provide an estimate of access and use, but cannot be used to determine collaboration between CBI practitioners featured on the map. The use of the map as a means to enhance collaboration will be explored through the CO-OPS annual national survey and future social network analysis.

Implications

The map provides a unique snapshot of Australian CBI, with one-in-five initiatives meeting proposed best practice in implementing multiple strategies. While this is promising, it also points to opportunities for further professional development to ensure practitioners understand, promote and are supported in the implementation of a multi-strategy, multi-level obesity prevention response.

Future research

A stronger understanding of the cost-benefit relationship between funding for prevention and a reduced burden of disease through overweight and obesity is required. A more detailed explanation (e.g. funding sources) of reasons for the adoption of a stronger multi-strategy platform by some CBI could inform future investment and development of preventive health responses.

Acknowledgments

CO-OPS is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health ITA 112/1112 Chronic Disease Prevention and Service Improvement Fund.

References

- Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. , et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statisitcs. Australia's Health Survey – Updated Results 2011–2012. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study 2010 [Internet] Seattle (wA): IHME; 2010. [cited 2014 Mar 3]. Available from: http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/sites/default/files/country-profiles/GBD20%Country20%Report20%-20%Australia.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva-Sanigorski AM, Bolton K, Haby M, Kremer P, Gibbs L, Waters E. Scaling up community-based obesity prevention in Australia: Background and evaluation design of the Health Promoting Communities: Being Active Eating Well initiative. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-65. , et al. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economos CD, Tovar A. Promoting health at the community level: Thinking globally, acting locally. Child Obes. 2012;8(1):19–22. doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haby M, Doherty R, Welsh N, Mason V. Community-based interventions for obesity prevention: Lessons learned by Australian policy-makers. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar L, Robertson N, Allender S, Nichols M, Bennett C, Swinburn B. Increasing community capacity and decreasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in a community based intervention among Australian adolescents. Prev Med. 2013;56(6):379–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, deSilva Sanigorski A, Hall B, Brown T, Campbell K, Yao G. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester (UK): John Wiley; 2011. Interventions for preventing obesity in children (Cochrane Review) 2011, et al. In:; Issue 12, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y, Wilson R, Wang Y. Systematic Review of Community-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Studies. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e201–e10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzel C, D'Afflitti J. Reconsidering community-based health promotion: Promise, performance, and potential. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):557–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak C, Heitmann BL, Summerbell C, Lissner L. Prevention of childhood obesity – what type of evidence should we consider relevant? Obes Rev. 2009;10(3):350–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn B, Bell C, King L, Magarey A, O'Brien K, Waters E. Obesity prevention programs demand high-quality evaluations. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(4):305–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00075.x. , et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols MS, Reynolds RC, Waters E, Gill T, King L, Swinburn BA. Community-based efforts to prevent obesity: Australia-wide survey of projects. Health Promot J Austr. 2013;24:111–117. doi: 10.1071/HE13001. , et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health [Internet] Canberra (AUST): Commonwealth of Australia; 2008. [cited 2014 Apr 11]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/phd-prevention-np. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs A. Health Funding Agreements [Internet] Canberra (AUST): Australian Parliamentary Library; 2014. [cited 2014 Jun 7]. Available from: http://www.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary_departments/parliamentary_library/pubs/rp/budgetreview201415/healthfunding. [Google Scholar]

- New South Wales Health. Get Healthy at Work [Internet] Sydney (AUST): State Government of Australia; 2014. [cited 2014 Jul 23]. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/healthyworkers/pages/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- The Australian National Preventive Health Agency. Shape Up Australia [Internet] Canberra (AUST): Commonwealth of Australia; 2013. [cited 2014 Jul 23]. Available from: http://www.shapeup.gov.au/ [Google Scholar]

- Cleland V, McNeilly B, Crawford D, Ball K. Obesity prevention programs and policies: Practitioner and policy-maker perceptions of feasibility and effectiveness. Obesity. 2013;21(9):e448–e55. doi: 10.1002/oby.20172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Swinburn B, Uauy R, Seidell J. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Evidence, Policy and Practice. Oxford (UK): Wiley Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- King L, Gill T, Allender S, Swinburn B. Best practice principles for community-based obesity prevention: Development, content and application. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):329–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]