Abstract

Introduction

Obesity is an increasing problem in the United States, and research into the association between obesity and pneumonia has yielded conflicting results.

Methods

Using Department of Veterans Affairs administrative data between fiscal years 2002-2006, we examined a cohort of patients hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of pneumonia. Body Mass Index was categorized as underweight (< 18.5), normal (18.5-24.9, reference group), overweight (25-29.9), obese (30-39.9), and morbidly obese (≥40). Our primary analyses were multi-level regression models with the outcomes of 90-day mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, need for mechanical ventilation and vasopressor utilization.

Results

The cohort comprised of 18,746 subjects. Three percent were underweight, 30% were normal, 35% were overweight, 26% were obese, and 4% were morbidly obese. In the regression models, after adjusting for potential confounders, morbid obesity was not associated with mortality (odds ratio 0.96, 95% confidence interval 0.72-1.28), but obesity was associated with decreased mortality (0.86, 95% 0.74-0.99). Neither obesity nor morbid obesity were associated with ICU admission, use of mechanical ventilation or vasopressor utilization. Underweight patients had increased 90-day mortality (1.40, 1.14-1.73).

Conclusions

Although obesity is a growing health epidemic, it appears to have little impact on clinical outcomes and may reduce mortality for veterans hospitalized with pneumonia.

BACKGROUND

In the United States, pneumonia affects approximately 4 million individuals per year [1] and, in combination with influenza, is the eighth leading cause of death and the leading cause of infectious death [2]. Despite the major impact of pneumonia on mortality, little attention has been focused on potential contributors to pneumonia-associated deaths [3].

Obesity is an increasing problem in the United States and globally. In 2005, the World Health Organization reported that worldwide, 1.6 billion adults were overweight and 400 million adults were obese. As the obesity epidemic grows, an estimated 2.3 billion adults will be overweight and 700 million adults will be obese by 2015 [4]. Obesity has been shown to be an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality [5-8], and it has been established that obese individuals have higher rates of mortality from ischemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes, renal disease, and liver disease [9].

Obesity has been identified as a risk factor for the development of a variety of infections. The positive association between obesity and infection has been well described [10-13], and it is known that obese individuals demonstrate altered lung function [14]. When these underlying alterations in lung function are considered in combination with the increased risk of infection in this patient population, it can be hypothesized that obese patients may be more likely to develop pneumonia and be at an increased risk for morbidity and mortality. There is a surprising lack of clinical data regarding the impact of obesity on pneumonia, and the studies that have been published to date demonstrate conflicting results [15-20].

Some studies suggest that obese patients are at increased risk for the development of pneumonia [16], while others do not support that association [15, 18]. Additionally, the relationship between obesity and mortality secondary to pneumonia is uncertain, as it appears that obesity has little clinical impact on pneumonia outcomes [19], and in several studies has been associated with reductions in mortality [17] [20].

The increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States, coupled with the uncertainty as to whether obese patients are at an increased risk of adverse pneumonia-related outcomes, makes this topic an area deserving of additional research. Therefore the aim of this study was to examine the effect of obesity on clinical outcomes for veterans hospitalized with pneumonia after adjusting for potential confounders. Our a priori hypothesis was that obesity would be associated with worse clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with pneumonia.

METHODS

We used data from the administrative databases of the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system (VA) [21]. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio approved this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients who had at least one outpatient clinic visit during fiscal year 2002, were hospitalized during fiscal year 2002 through the first half of fiscal year 2009 with a previously validated discharge diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) codes 480.0–483.99 or 485–487.0) or a secondary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia with a primary diagnosis of respiratory failure (ICD-9 code 518.81) or sepsis (ICD-9 code 038.xx) [22], and who received at least one dose of an antibiotic within 48 hours of admission, were included in this study.

Data Sources and Population

This retrospective study utilized sociodemographic, diagnostic, anthropometric, mortality, utilization, and pharmacy data. Sociodemographic data included age, gender, ethnicity, and marital status. We also collected VA priority status, which consists of 9 categories related to disability and income. We assigned patients to underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2), obese (BMI 30-39.9 kg/m2), and morbidly obese (BMI ≥40 kg/m2), according to their baseline BMI in 2002. We assessed the presence of prior comorbid conditions by reviewing data from inpatient and outpatient administrative records using the Charlson-Deyo system [23-25].

Outcomes

Outcomes were 90-day mortality, ICU admission, use of mechanical ventilation, and use of vasopressors. Mortality was assessed using the VA vital status file [26].

Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables were analyzed using the Χ2 test and continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t test. We defined statistical significance using a two-tailed p<0.01.

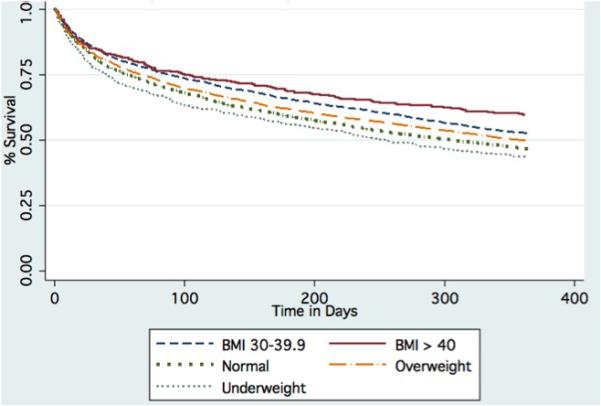

For our primary analyses, we used generalized linear mixed-effect models with the patient's hospital as a random effect. We created separate models for each of the outcomes of interest, with the patient's BMI class (normal weight as the reference group) and potential confounders as the independent variables. We included variables as covariates in the models if we hypothesized a priori that they would be associated with obesity or the outcome(s). Covariates included in the models were age, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, count of current medications, medical and psychiatric comorbid conditions, alcohol abuse, tobacco use, and drug abuse. In addition, for the outcome of 90-day mortality, we included ICU admission, use of mechanical ventilation, and use of vasopressors as covariates. We examined interaction terms between age and individual BMI classes, however, since they were not statistically significant we excluded them from the final models. To analyze time-to-death for patients by weight class, we used a Kaplan-Meier graph to display the survivor functions.

All analyses were performed using STATA 10 (College Station, Texas) and SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

There were 18,746 patients who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The mean age was 67.5 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 11.9 years, 97% were male, and 54% were married. By ethnicity and race, 65% were Caucasian, 22% were African American, 11% were Hispanic and 2% were of other race. When characterized according to BMI, 3% were underweight, 30% normal weight, 36% overweight, 27% obese, and 4% morbidly obese.

Table 1 shows the baseline patient characteristics separated by BMI categories. Statistically significant differences in chronic disease were noted between the obese and morbidly obese patients and the underweight patients. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus increased as BMI increased with 79% of morbidly obese patients and 63% of obese patients carrying a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus compared to 26% of normal weight and 12% of underweight patients (p<0.0001). Also significant was the history of congestive heart failure (CHF), with 58% of morbidly obese and 47% of obese patients carrying a diagnosis of a CHF versus 29% of normal weight patients and 19% of underweight patients (p <0.0001). Obese and morbidly obese patients were also more likely to have a previous myocardial infarction and chronic renal disease.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by Body Mass Index classification

| Variable | Underweight (BMI <18.5) N = 650 | Normal (BMI 18.5 - 24.9) N = 5,653 | Overweight (BMI 25 - 29.9) N = 6,689 | Obese (BMI 30 - 39.9) N = 5,012 | Morbidly Obese (BMI ≥40) N = 742 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 69.0 (3.5) | 69.0 (12.3) | 68.5 (11.7) | 65.4 (11.3) | 59.8 (10.4) |

| Male | 626 (96.3) | 5,492 (97.2) | 6,549 (97.9) | 4,840 (96.6) | 703 (94.7) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 417 (64.7) | 3,693 (65.5) | 4,216 (63.2) | 3,354 (67.0) | 501 (67.7) |

| Black | 135 (20.9) | 1,190 (21.1) | 1,504 (22.6) | 1,130 (22.6) | 188 (25.4) |

| Hispanic | 86 (13.3) | 677 (12.0) | 807 (12.1) | 445 (8.9) | 43 (5.8) |

| Other / Unknown | 7 (1.1) | 75 (1.3) | 144 (2.2) | 78 (1.6) | 8 (1.1) |

| Married | 284 (43.7) | 2,824 (50.0) | 3,792 (56.7) | 2,858 (57.0) | 392 (52.8) |

| Medical Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 80 (12.3) | 1,470 (26.0) | 2,926 (43.7) | 3,160 (63.1) | 586 (79.0) |

| Diabetes with complications | 24 (3.7) | 600 (10.6) | 1,385 (20.7) | 1,725 (34.4) | 349 (47.0) |

| AIDS | 12 (1.9) | 117 (2.1) | 75 (1.1) | 45 (0.9) | 4 (0.5) |

| Cancer | 222 (34.2) | 2,066 (36.6) | 2,466 (36.9) | 1,620 (32.3) | 177 (23.9) |

| Stroke | 134 (20.6) | 1,721 (30.4) | 2,208 (33.0) | 1,568 (31.3) | 154 (20.8) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 124 (19.1) | 1,633 (28.9) | 2,442 (36.5) | 2,358 (47.1) | 432 (58.2) |

| Cirrhosis | 16 (2.5) | 155 (2.7) | 210 (3.1) | 183 (3.7) | 20 (2.7) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 513 (78.9) | 4,051 (71.7) | 4,570 (68.3) | 3,600 (71.8) | 575 (77.5) |

| Hepatic Failure | 3 (0.5) | 69 (1.2) | 100 (1.5) | 90 (1.8) | 7 (0.9) |

| HIV | 5 (0.8) | 68 (1.2) | 49 (0.7) | 24 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

| Leukemia | 13 (2.0) | 170 (3.0) | 259 (3.9) | 184 (3.7) | 16 (2.2) |

| Myocardial Infarction | 54 (8.3) | 641 (11.3) | 993 (14.9) | 711 (14.2) | 94 (12.7) |

| Perivascular Disease | 148 (22.8) | 1,531 (27.1) | 1,990 (29.8) | 1,477 (29.5) | 191 (25.7) |

| Hemiplegia/Paraplegia | 13 (2.0) | 156 (2.8) | 179 (2.7) | 119 (2.4) | 14 (1.9) |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 58 (8.9) | 496 (8.8) | 548 (8.2) | 352 (7.0) | 34 (4.6) |

| Renal Disease | 60 (9.2) | 958 (17.0) | 1,577 (23.6) | 1,377 (27.5) | 202 (27.2) |

| Rheumatologic Disease | 21 (3.2) | 263 (4.7) | 371 (5.6) | 257 (5.1) | 45 (6.1) |

| Cancer with metastasis | 36 (5.5) | 385 (6.8) | 463 (6.9) | 298 (6.0) | 23 (3.1) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | |||||

| Alcohol use disorder | 70 (10.8) | 533 (9.4) | 409 (6.1) | 238 (4.8) | 19 (2.6) |

| Substance use disorder | 7 (1.1) | 137 (2.4) | 143 (2.1) | 116 (2.3) | 12 (1.6) |

| Tobacco dependence | 46 (7.1) | 368 (6.5) | 429 (6.4) | 339 (6.8) | 59 (8.0) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 19 (2.9) | 157 (2.8) | 198 (3.0) | 220 (4.4) | 43 (5.8) |

| Dementia | 63 (9.7) | 517 (9.2) | 480 (7.2) | 199 (4.0) | 12 (1.6) |

| Psychotic disorders | 20 (3.1) | 260 (4.6) | 301 (4.5) | 250 (5.0) | 46 (6.2) |

There were also statistically significant differences in chronic diseases in the normal weight and underweight populations. It is notable that 34% of underweight and 37% of normal weight patients had a prior diagnosis of malignancy versus 32% of obese and 24% of morbidly obese patients (p<0.0001). The prevalence of dementia was also significant with 10% of underweight and 9% of normal weight versus 4% of obese and 2.0% of morbidly obese patients with a diagnosis of dementia.

Univariate Outcomes

Overall mortality at 90 days was 18%. Obese and morbidly obese patients had a decreased 90-day mortality compared to underweight and normal weight patients (30% underweight, 22% normal weight, 13% obese and 11% morbidly obese; p <0.0001; Table 2). Overall 19% of patients needed ICU admission and there were no statistically significant differences in BMI categories. For the outcome of mechanical ventilation, which was used in 2% of the patients overall, there was no statistically significant difference when broken into BMI categories. Vasopressors were used in 5% of patients, and there were no statistically significant differences in vasopressor utilization when separated by BMI categories.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes by Body Mass Index classification

| Variable | Underweight (BMI <18.5) N = 650 | Normal (BMI 18.5 - 24.9) N = 5,653 | Overweight (BMI 25 - 29.9) N = 6,689 | Obese (BMI 30 - 39.9) N = 5,012 | Morbidly Obese (BMI >40) N = 742 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | |||||

| At 30-days post admission | 124 (19.1) | 744 (13.2) | 699 (10.5) | 388 (7.7) | 52 (7.0) |

| At 90-days post admission | 193 (29.7) | 1,225 (21.7) | 1,171 (17.5) | 668 (13.3) | 83 (11.2) |

| ICU Admission | 141 (21.7) | 1,057 (18.7) | 1,138 (17.7) | 928 (18.5) | 152 (20.5) |

| Died in ICU | 43 (30.5) | 193 (18.3) | 214 (18.1) | 125 (13.5) | 25 (16.5) |

| Died in Hospital | 59 (41.8) | 286 (27.1) | 203 (25.6) | 178 (19.2) | 33 (21.7) |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 19 (2.9) | 121 (2.1) | 128 (1.9) | 106 (2.1) | 18 (2.4) |

| Vasopressor Use | 42 (6.5) | 288(5.1) | 293(4.4) | 254(5.1) | 33(4.4) |

Multilevel Regression Models

In the regression models (Table 3), after adjusting for potential confounders, there was a statistically significant association with decreased mortality for obese patients (odds ratio [OR] 0.86, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.74–0.99), no association for morbidly obese patients (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.72–1.28), and an association with increased mortality in underweight patients (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.14 -1.73). There was no association with ICU admission for obese (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.84–1.13) or morbidly obese patients (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.76–1.28).

Table 3.

Multilevel Regression Analyses of Clinical Outcomes by Body Mass Index Classification

| Body Mass Index Classification | 90-Day Mortality OR (95% CI) | ICU Admission OR (95% CI) | Mechanical Ventilation OR (95% CI) | Vasopressor Use OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 1.40 (1.14 - 1.73) | 1.17 (0.92 - 1.48) | 1.22 (0.70 - 2.13) | 1.30 (0.86 - 1.96) |

| Overweight (BMI 25-29.9) | 0.87 (0.79 - 0.97) | 0.96 (0.86 - 1.01) | 1.00 (0.75 - 1.33) | 0.93 (0.76 - 1.15) |

| Obese (BMI 30-39.9) | 0.86 (0.74 - 0.99) | 0.98 (0.84 - 1.13) | 0.92 (0.63 - 1.35) | 1.19 (0.91 - 1.56) |

| Morbidly Obese (BMI ≥40) | 0.96 (0.72 - 1.28) | 1.00 (0.79 - 1.28) | 1.16 (0.62 - 2.16) | 0.95 (0.59 - 1.50) |

Regarding mechanical ventilation, there was no significant association for obese and morbidly obese patients with mechanical ventilation (obese OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.63–1.25; morbidly obese OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.62–2.16). In addition, there were no significant associations with vasopressor use (obese OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.91-1.56; morbidly obese OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.59–1.52). Due to the increased prevalence of CHF, diabetes, and renal disease in the obese and morbidly obese patients, and the increased prevalence of dementia in the normal and underweight patients, interaction terms between the BMI categories and the aforementioned variables were examined. No significant interactions were found, so we did not include these interactions terms in the final models.

DISCUSSION

The relationship between obesity and pneumonia has recently become a subject of more intensive research, and there is a lack of consensus regarding the impact of obesity on the development of and outcomes after pneumonia. Despite our hypothesis that obese patients hospitalized with pneumonia would have worse clinical outcomes, we found that after adjusting for potential confounders, obese patients actually had a lower 90-day mortality rate. Additionally, morbidly obese patients did not show an increase or decrease in mortality, and underweight patients demonstrated an increase in 90-day mortality. We did not discover any significant associations with regards to ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor use in either obese or morbidly obese patients.

Unlike the conflicting results regarding obesity and pneumonia, a clear relationship between obesity and an increased risk of infection has been well-described [10]. Obese individuals are at risk for a variety of infections, including bacteremia, catheter related infections [11], surgical site infections [12], poor wound healing, and nosocomial infections [13]. Recent studies examining the epidemiological data regarding the recent H1N1 outbreak have also linked obesity to increased incidence of infection [27], increased mortality [28], severity of infection with the H1N1 virus, and increased likelihood of requiring ICU admission [29]. Obese individuals have also demonstrated changes in underlying immune function, with alterations in lymphocyte and monocyte function resulting in a relative immunodeficient state, which leads to increased susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections [30].

The relationship between obesity and chronic respiratory diseases, such as obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome, has also been well-described [31]. Obese individuals demonstrate altered lung function, including diminished lung volumes, decreased respiratory compliance, reduction in gas exchange, impaired respiratory muscle function, and an increase in airway resistance [14]. Given this demonstrated increased risk of infection to both bacterial and viral pathogens and the underlying alterations in lung function, it is logical to theorize that obese patients would be at increased risk for both the development of pneumonia and for worse clinical outcomes. However, the relationship between obesity and pneumonia has yet to be clearly defined. Results from several previous studies concerning the relationship between obesity, pneumonia and mortality have yielded intriguing results. It would be intuitive to assume that obese patients would be more likely to have adverse clinical outcomes and increased mortality secondary to pneumonia, however the clinical data that is currently available has not supported this hypothesis. The first of such studies performed by LaCroix et. al [19] is a prospective study examining the effect of chronic conditions, nutritional status, and health behaviors on pneumonia mortality. They found that patients with low BMIs had higher pneumonia mortality compared to those with high BMIs.

More recent data on the relationship between obesity and pneumonia mortality supports our findings of the association between obesity and decreased mortality. Inoue et. al [20] performed a systematic review to ascertain the risk and protective factors of obesity for pneumonia mortality. As in our study, they found that obese patients had a reduction in pneumonia mortality compared to normal weight patients (OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.5-0.8), which was maintained after adjusting for age and the presence of diabetes. A retrospective study by Corrales et.al [17] corresponds to this data, showing that in patients with proven bacterial pneumonia, obesity was associated with decreased 30 day mortality, which was again maintained in multivariable analysis (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.81-0.96). Our study adds to this growing body of evidence and points toward an underlying factor that obese patients have, which affords them protection against adverse outcomes secondary to pneumonia.

One of the reasons for this possible protective effect against pneumonia may be due to an altered inflammatory response in the lung tissue of obese patients. Prior studies have shown that increasingly elevated inflammatory cytokine levels are associated with increased mortality from acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [32-35]. It has also been shown that baseline inflammatory cytokine levels increase in proportion to BMI, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 [36-38]. Stapleton et al. [39] examined this relationship in a retrospective study of 1409 participants in the NHLBI ARDS trials. Plasma levels of IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor 1, surfactant protein D (SP-D) soluble intracellular adhesion molecule, vonWillebrad Factor (vWF), Protein C and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 were all measured at baseline and on hospital day 3, and then these levels were correlated with BMI. It was found that IL-6, IL-8 and SP-D were inversely related to BMI while vWF increased proportionally with BMI. The inversely related IL-6, IL-8 and SP-D levels suggest that obese patients may have an attenuated response in inflammation and less alveolar epithelial injury during infection, which could help protect against further lung injury, increased mortality, and use of mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, given that this patient population has an already elevated level of inflammatory markers at baseline, the relative increase in inflammation would be smaller than patients of normal BMI, which also could lessen alveolar injury and potentially help explain our findings.

Another possible explanation could be related to differences in the immunological function of obese patients. Studies have demonstrated that obese individuals have increased serum levels of leptin, a protein hormone produced by adipocytes that participates in the function of both innate and adaptive immunity [40]. Leptin has been shown to increase macrophagic activity, neutrophil chemotaxis, cytotoxicity of natural killer cells, and T-cell and B-cell lymphopoeisis, all of which helps to promote bacterial clearance [41]. Therefore, one could postulate that increased leptin levels could help to enhance the immune response of obese individuals and perhaps serve as a protective role against infection. Both the role of inflammation and the immunological effects of obesity are intriguing areas of study and deserve further research to fully understand their clinical impact.

While the aim of this study was to examine the relationship between obesity and pneumonia outcomes, in congruence with prior studies [19, 20, 42, 43] our study also found that underweight patients had an increase in 90-day mortality, ICU mortality and in-hospital mortality after ICU admission. This could be secondary to unaccounted effects of the underlying diseases (malignancy, dementia, AIDS) that are more prevalent in the underweight patient population. Such effects may include malnutrition or an immunocompromised state, which would increase their risk for infection or mortality after illness.

There are several limitations of our study. This study consisted of patients hospitalized at VA medical centers, and therefore the results may not be directly applicable to other patient populations. Another limitation is that due to the high prevalence of males in the VA health care system, 97% of the patients included in this study were male; thus, it is unclear whether the same results would have obtained if our study population had a male to female ratio more representative of the general population. Also, the inclusion criteria for our study relied on the use of a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia and most diagnoses were likely obtained radiographically. This raises the possibility of over-diagnosis of pneumonia in obese and morbidly obese patients due to body habitus and poor visualization of lung fields, which could also explain why obese patients seemed to have better clinical outcomes. Finally, due to the data source, we were unable to examine pathogens or adjust for severity of illness at presentation. It is possible that obese patients present earlier to the hospital due to “breathlessness” and this is the reason for our findings.

In conclusion, although obesity is a rapidly growing health care crisis and obese patients provide health care teams with unique challenges, they do not appear to be at increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes after hospitalization with pneumonia. Despite the negative ramifications that are associated with obesity, our study has shown that it may actually provide a protective effect against increased pneumonia mortality. The reasons behind these results are unclear and further investigation into the exact relationship between pneumonia and obesity, and the possible mechanisms behind its protective effect, is warranted to fully understand and appreciate how obesity affects the severity and mortality of patients admitted for pneumonia.

Figure 1.

Time to Death by BMI Class

Acknowledgments

Support/Disclosures: The project described was supported by VA HSR&D grant IIR 05-121. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System. The funding agencies had no role in conducting the study, or role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartlett JG, Mundy LM. Community-acquired pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333(24):1618–1624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, et al. Deaths: Final data for 2005. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mortensen EM, Coley CM, Singer DE, et al. Causes of death for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(9):1059–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.9.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Obesity and overweight. [2011 February 17];Fact Sheet 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html.

- 5.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(23):2211–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, et al. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293(15):1861–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, et al. Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(15):1097–105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(8):763–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1083–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falagas ME, Kompoti M. Obesity and infection. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2006;6(7):438–46. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dossett LA, Dageforde LA, Swenson BR, et al. Obesity and site-specific nosocomial infection risk in the intensive care unit. Surgical Infections. 2009;10(2):137–42. doi: 10.1089/sur.2008.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. The obese surgical patient: a susceptible host for infection. Surgical Infections. 2006;7(5):473–80. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.7.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle SL, Lysaght J, Reynolds JV. Obesity and post-operative complications in patients undergoing non-bariatric surgery. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(12):875–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murugan AT, Sharma G. Obesity and respiratory diseases. Chronic Respiratory Disease. 2008;5(4):233–42. doi: 10.1177/1479972308096978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Serra-Prat M, et al. New evidence of risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based study. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(6):1274–84. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00095807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baik I, Curhan GC, Rimm EB, et al. A prospective study of age and lifestyle factors in relation to community-acquired pneumonia in US men and women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(20):3082–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.20.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrales-Medina VF, Valayam J, Serpa JA, et al. The obesity paradox in community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2011;15(1):e54–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnoor M, Klante T, Beckmann M, et al. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in German adults: the impact of children in the household. Epidemiology and infection. 2007;135(8):1389–97. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807007832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacroix AZ, Lipson S, Miles T, et al. Prospective study of pneumonia hospitalizations and mortality of U.S. older people: the role of chronic conditions, health behaviors, and nutritional status. Public Health Reports. 1989;104:350–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue Y, Koizumi A, Wada Y, et al. Risk and protective factors related to mortality from pneumonia among middleaged and elderly community residents: the JACC Study. Journal of epidemiology / Japan Epidemiological Association. 2007;17(6):194–202. doi: 10.2188/jea.17.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown SH, Lincoln MJ, Groen PJ, et al. VistA--U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs national-scale HIS. International journal of medical informatics. 2003;69(2-3):135–56. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meehan TP, Fine MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Quality of care, process, and outcomes in elderly patients with pneumonia. JAMA. 1997;278(23):2080–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Medical Care. 2004;42(4):355–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118861.56848.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, et al. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Population health metrics. 2006;4:2–12. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothberg MB, Haessler SD. Complications of seasonal and pandemic influenza. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(4 Suppl):e91–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c92eeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui W, Zhao H, Lu X, et al. Factors associated with death in hospitalized pneumonia patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in Shenyang, China. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viasus D, Paño-Pardo JR, Pachón J, et al. Factors associated with severe disease in hospitalized adults with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in Spain. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlsson EA, Beck MA. The burden of obesity on infectious disease. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2010;235(12):1412–24. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piper AJ, Grunstein RR. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: mechanisms and management. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011;183(3):292–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1280CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsons PE, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, et al. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000149854.61192.dc. discussion 230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware LB, Matthay MA, Parsons PE, et al. Pathogenetic and prognostic significance of altered coagulation and fibrinolysis in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(8):1821–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000221922.08878.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClintock D, Zhuo H, Wickersham N, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation and fibrinolysis predict mortality in acute lung injury. Critical Care. 2008;12(2):R41. doi: 10.1186/cc6846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware LB, Koyama T, Billheimer DD, et al. Prognostic and pathogenetic value of combining clinical and biochemical indices in patients with acute lung injury. Chest. 2010;137(2):288–96. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mancuso P. Obesity and lung inflammation. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2010;108(3):722–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00781.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim CS, Park HS, Kawada T, et al. Circulating levels of MCP-1 and IL-8 are elevated in human obese subjects and associated with obesity-related parameters. International Journal of Obesity. 2006;30(9):1347–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2005;69(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stapleton RD, Dixon AE, Parsons PE, et al. The association between BMI and plasma cytokine levels in patients with acute lung injury. Chest. 2010;138(3):568–77. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iikuni N, Lam QL, Lu L, et al. Leptin and Inflammation. Current Immunology Reviews. 2008;4(2):70–79. doi: 10.2174/157339508784325046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam QL, Lu L. Role of leptin in immunity. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. 2007;4(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Serra-Prat M, et al. New evidence of risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based study. European respiratory journal. 2008;31(6):1274–84. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00095807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnoor M, Klante T, Beckmann M, et al. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in German adults: the impact of children in the household. Epidemiology and Infection. 2007;135(8):1389–97. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807007832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]