Abstract

The introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has significantly increased survival rate and quality of life for patients with CML. Despite the high efficacy of imatinib, not all patients benefit from this treatment. Resistance to imatinib can develop from a number of mechanisms. One of the main reasons for treatment failure is a mutation in the BCR-ABL gene, which leads to therapy resistance and clonal evolution. Clearly, new treatment approaches are required for patients who are resistant to imatinib. However, mutated clones are usually susceptible to second-generation TKIs, such as nilotinib and dasatinib. The choice of the therapy depends on the type of mutation. A large trial program showed that dasatinib is effective in patients previously exposed to imatinib. However, for a minority of patients who experience treatment failure with TKI or progress to advanced-phase disease, allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) remains the therapeutic option. In spite of the high curative potential of allo-SCT, its high relapse rate still requires a feasible strategy of posttransplant treatment and prophylaxis. We report a case of a CML patient with primary resistance to first-line TKI therapy. The patient developed an undifferentiated blast crisis. Before dasatinib therapy, the patient was found to have an F317L mutation. He was successfully treated with dasatinib followed by allo-SCT. In the posttransplant period, preemptive dasatinib treatment was used to prevent disease relapse.

Keywords: CML, TKI, dasatinib, BCR-ABL mutations, F317L mutation, allo-SCT

Background

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by uncontrolled growth of bone marrow myeloid progenitor cells. CML is defined by the presence of reciprocal translocation t(9;22), (q34;q11), which determines the formation of the BCR-ABL fusion gene with constitutively active tyrosine kinase.1,2 With the development of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that specifically target BCR-ABL activity, the treatment of CML patients has modified rapidly.3 Imatinib therapy resulted in significantly better patient outcome, response rates, and overall survival compared with previous standards.4–6 Despite this advance, not all patients benefit from imatinib because of resistance and intolerance. Approximately one-third of imatinib-treated patients discontinue therapy because of an inadequate response or toxicity.3,7 There is a whole range of possible reasons for lack of effect from imatinib. The most significant mechanisms of imatinib resistance involve point mutations in the ABL kinase domain, leading to structural changes in this domain and overexpression of BCR-ABL.8–10 In addition, imatinib resistance in some patients may be mediated through loss of kinase target dependence11 or clonal evolution and amplification of chimeric genes.9 BCR-ABL-independent mechanisms, such as poor intestinal absorption, drug interactions, and wrong drug administration, have also been implicated.9,12

There are currently more than 90 known BCR-ABL gene mutations that are able to cause TKI resistance.13 They are rarely found in newly diagnosed patients, but their incidence increases in the first year of imatinib therapy, reaching 30%–90% in cases of secondary resistance.14 It has frequently been shown that the incidence of mutations is different in various phases of CML, ranging from 25% to 30% of early chronic-phase (CML-CP) patients to 70%–80% of blast crisis (CML-BC) patients. In addition, BCR-ABL mutations are more commonly detected in cases with acquired resistance than in cases with primary resistance.14–16

Introduction of second-generation TKIs such as nilotinib and dasatinib did not solve the problem completely. However, the spectrum of mutations that can cause resistance to second-generation TKIs is considerably less than that for imatinib.15,17 It should be noted that a BCR-ABL mutated cell clone resistant to treatment with one of the drugs may be sensitive to the other one.14

Only the T315I mutation causes complete failure of treatment with first- and second-generation TKIs. Recently, third-generation TKIs have been developed to overcome the inhibitory effect of this mutation.18 The Food and Drug Administration approved this drug in 2012, but clinical application is limited due to toxicity and extremely high price. Thus, the inclusion of other treatment modalities such as allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) is required in patients.19–21

Although after the introduction of TKIs, the role of allo-SCT therapy for CML patients has significantly decreased, it is still currently a curative treatment option for CML-BC patients.22 Resistance to TKI treatment and detection of mutations, especially T315I mutation, are common indications for allo-SCT. Moreover, experts recommend continuing TKI treatment after allo-SCT as consolidation therapy.22 Also, TKIs have shown promising effects in patients with relapse after transplantation.23–25

Case Presentation

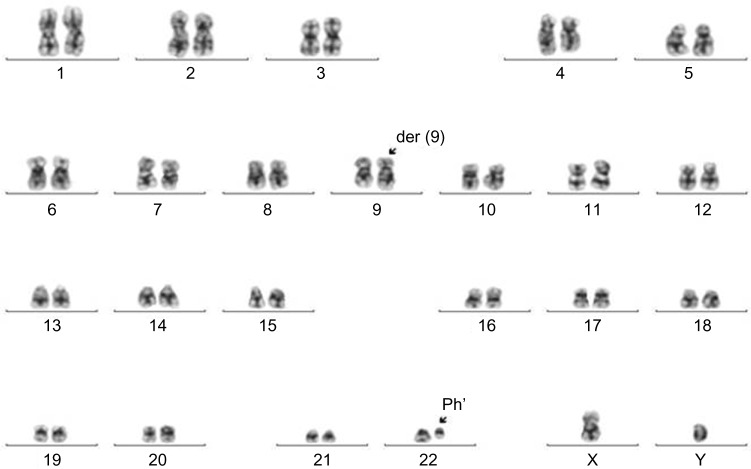

A 23-year-old male was diagnosed with CML-CP (low Sokal score, 0.6) in April 2009. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical guidelines of our institution. Routine laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (30/nL) and thrombocytopenia (40/nL). Cytogenetic and molecular genetic analyses developed the presence of a translocation t(9;22) (q34;q11) (Fig. 1) and chimeric BCR-ABL mRNA transcripts. From May to June 2009, the patient received cytotoxic therapy with hydroxyurea. From June 2009, he was treated with imatinib (400 mg daily). Four weeks later, complete hematologic response (CHR) was achieved. Two months later, complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) was achieved.

Figure 1.

The translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) in bone marrow at diagnosis. Karyotype abnormality was revealed by cytogenetic analysis using standard G-banding technique: 46,XY,t(9;22)(q34;q11). The t(9;22)(q34;q11) was found in 20 metaphases at diagnosis. Two marker chromosomes are indicated by arrow: der9q and Ph’. Der indicates derivate, Ph’ indicates Philadelphia chromosome, 22q-.

In December 2009, six months after initiation of imatinib therapy, routine laboratory investigations revealed leukocytosis (20.3/nL) with 65% of blast cells on peripheral smear and 81% of blast cells in bone marrow. Immunophenotyping and cytochemistry analysis corresponded to undifferentiated, mixed-phenotype blast crisis. Using cytogenetic analysis, translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) without additional chromosomal abnormalities was found in 90% of mitosis, and normal karyotype was determined in 10% of metaphases. Using Sanger sequencing for mutational analysis of BCR-ABL, mutation F317L was detected. From December 2009 to January 2010, the patient was treated with dasatinib (140 mg daily) and hydroxyurea (2–3 g daily). From January 2010, the patient received daily 140 mg of dasatinib as monotherapy. After this treatment, the patient again reached a CHR.

Subsequently, the patient was scheduled for allo-SCT. According to EBMT criteria for CML, the patient was at low risk.26 In April 2010, 12 months after initial diagnosis, match-related allo-SCT was performed. Because of the young age of the patient, absence of comorbidity, good performance status, and CHR before allo-SCT, myeloablative conditioning was chosen. The myeloablative conditioning regimen consisted of busulfan (16 mg/kg), cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg body weight), and antithymocyte globulin (ATGAM; Pfizer). For prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), the patient received tacrolimus and methotrexate. The count of CD34+cells in the graft was 12.2 × 106/kg body weight. On day 17 after allo-SCT, platelet and neutrophil engraftment were obtained. No signs of acute GvHD were seen.

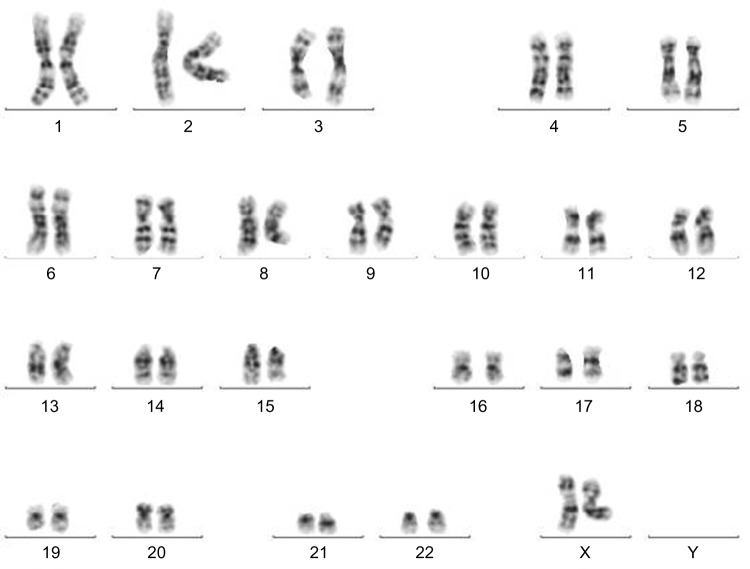

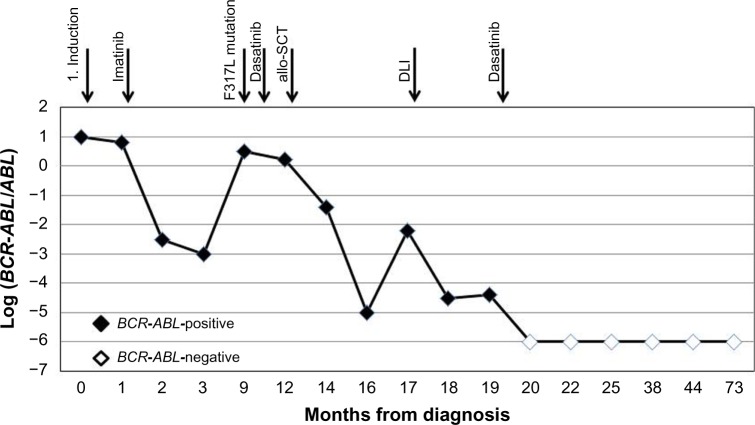

At day +129 after allo-SCT, repeated BCR-ABL monitoring showed an increased level of chimeric genes in the bone marrow. Withdrawal of immunosuppression and immunoadoptive therapy (donor lymphocytes infusion [DLI]) in combination with dasatinib (140 mg daily) was begun. Reduction of immunosuppressive therapy instigated the appearance of chronic GvHD with the involvement of skin and mucosa. Thus, the patient received tacrolimus (0.25 mg daily). When the DLI was stopped, the therapy with dasatinib (100 mg daily) was continued. At day +158 after allo-SCT, HCR, CCyR, and deep molecular response (MR4.5) were determined. From October 2011 to date, repeated cytogenetic and molecular genetic analyses demonstrated normal female donor karyotype (Fig. 2), complete donor chimerism, and no detected disease at the molecular level. The monitoring of the patient’s response to therapy is demonstrated in Figure 3. Currently, the patient is alive with a follow-up of five years after allo-SCT in clinical, hematological, and cytogenetic remission, with complete molecular response and complete donor chimerism. He receives dasatinib as a prophylactic treatment (100 mg daily).

Figure 2.

Normal female karyotype after allo-SCT. Normal female donor karyotype was found in bone marrow cells after allo-SCT: 46,XX.

Figure 3.

The monitoring of the patient’s response to therapy. Responses of the patient to therapy with imatinib, dasatinib, and allo-SCT were estimated by BCR-ABL transcript levels. BCR-ABL were monitored using quantitative polymerase chain reaction either in the bone marrow or peripheral blood and expressed as the logarithmic ratio of BCR-ABL to the control gene ABL gene.

Discussion

The most common mechanisms for resistance in CML patients receiving imatinib are mutations in the kinase domain of the BCR-ABL gene.12 Some mutations have been confirmed to have clinical resistance to second generation of TKIs, and these are associated with poor outcome.12,13,15,27–29 Here, we present a CML patient who experienced disease progression after six months of therapy with imatinib. In CML-BC, mutation F317L was found. The F317L mutation results in an amino acid substitution at position 317 in BCR-ABL, from a phenylalanine (F) to a leucine (L). Frequency of BCR-ABL F317L mutation in BCR-ABL1-mutated CML is 5.7%. Presence of point mutations in BCR-ABL has been implicated as a mechanism for the development of imatinib resistance.14 In preclinical studies, F317L-mutated cell lines demonstrated decreased sensitivity to dasatinib and bosutinib, but comparatively little reduced sensitivity to nilotinib, compared with CML cell lines wild type for mutations.14 Moreover, some authors consider that F317L mutation can occur more often after dasatinib therapy and lead to resistance.30 Although F317L mutation confers reduced sensitivity to dasatinib, there are some previous reports of efficacy of dasatinib in CML patients with F317L mutation.31,32 National Comprehensive Cancer Network considers that nilotinib treatment rather than dasatinib could be recommended for imatinib-resistant CML patients with F317L mutation.14,33 On the contrary, Faber et al have found that the lack of dasatinib efficacy in patients with F317L is not absolute; some other biological factors could modify the treatment outcome.31 In our case, the patient with mixed CML-BC was resistant to imatinib therapy and responded well to dasatinib. CHR and CCyR were achieved four weeks after introduction of the therapy.

Since the patient was diagnosed with CML-BC, he was primarily considered a candidate for allo-SCT in order to achieve a CR. Currently, allo-SCT is recommended for eligible patients in advanced-phase CML and in instances of failure of and/or intolerance to TKI treatment.22 In view of the curative potential of allo-SCT, transplantation could become the preferred second-line option after failure of first-line TKI therapy for suitable patients with a donor.22 This therapy also enabled effective monitoring of minimal residual disease and hematopoietic chimerism after allo-SCT. The monitoring of treatment response in CML patients using both cytogenetic tests and BCR-ABL transcript levels is essential in the management of CML. Level of BCR-ABL transcript is the important prognostic factor that defines individual treatment.34 In our patient, increasing of BCR-ABL gene in bone marrow was detected at day +100 after allo-SCT. Given the high risk of relapse, withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy and DLI were used.

Treatment with DLI is a well-established therapeutic approach for CML patients who relapse after allo-SCT. Responses achieved after DLI are frequently durable, offering a potential cure for the majority of patients.35,36 After effective therapy with DLI, CHR and CCyR were detected. Then, the patient received therapy with dasatinib (100 mg daily).

There is limited published data available on the efficacy of TKIs both before and after allo-SCT. It has been shown that this combination is superior to TKI treatment alone and can improve outcome.37 Therefore, early allo-SCT after short-term TKI therapy should be the treatment of choice for CML-BC. Improved outcomes from the combination treatment may be because pretreatment with TKIs reduced the leukemia burden before allo-SCT, and more importantly, the individualized TKI-based intervention strategy based on TKIs and modified DLI posttransplant reduced the risk of relapse.37 Our data indicate that allo-SCT in combination with TKI is a better option for CML-BC patients. In addition, we confirmed that preemptive treatment with dasatinib (100 mg daily) is capable of preventing disease relapse after allo-SCT.

We conclude that F317L mutation is an informative prognostic biomarker. Despite conflicting data on the sensitivity of F317L mutation to the dasatinib,14,30–32 we have shown efficacy of dasatinib in combination with allo-SCT in CML-BC patients. Evidence indicating the resistance of mutation to dasatinib is mainly based on in vitro studies. The outcome of patients is related to complex factors. Future clinical studies are needed to assess the sensitivity of specific BCR-ABL mutations to TKI therapy.

Footnotes

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Karen Pulford, Editor in Chief

PEER REVIEW: Four peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 1,073 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: Authors disclose no funding sources.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review. All editorial decisions made by independent academic editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of competing interests and funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: KL, YV, MP, EM. Analyzed the data: EM, YV, MP, KL. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: EM, KL. Contributing to the writing the manuscript: EM, YV, MP, KL. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: EM, YV, MP, KL, BA. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: EM, YV, MP, KL, BA. Made critical revision and approved final version: EM, YV, MP, KL, BA. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rowley JD. Letter: a new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243(5405):290–3. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faderl S, Talpaz M, Kantarjian HM, Estrov Z. Should polymerase chain reaction analysis to detect minimal residual disease in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia be used in clinical decision making? Blood. 1999;93:2755–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, et al. IRIS Investigators Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2408–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. IRIS Investigators Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baccarani M, Saglio G, Goldman J, et al. European LeukemiaNet Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2006;108:1809–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Baccarani M. Chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):342–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarado Y, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, et al. Significance of suboptimal response to imatinib, as defined by the European LeukemiaNet, in the long-term outcome of patients with early chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase. Cancer. 2009;115(16):3709–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293(5531):876–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apperley JF, Part I. Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(11):1018–29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70342-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elias MH, Baba AA, Azlan H, et al. BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations, including 2 novel mutations in imatinib resistant Malaysian chronic myeloid leukemia patients – frequency and clinical outcome. Leuk Res. 2014;38(4):454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donato NJ, Wu JY, Stapley J, et al. Imatinib mesylate resistance through BCR-ABL independence in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64(2):672–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milojkovic D, Apperley J. Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib and second-generation tyrosine inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(24):7519–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller MC, Cortes JE, Kim DW, et al. Dasatinib treatment of chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: analysis of responses according to preexisting BCR-ABL mutations. Blood. 2009;114:4944–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soverini S, Hochhaus A, Nicolini FE, et al. BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2011;118:1208–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soverini S, Colarossi S, Gnani A, et al. GIMEMA Working Party on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Contribution of ABL kinase domain mutations to imatinib resistance in different subsets of philadelphia-positive patients: by the GIMEMA working party on chronic myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(24):7374–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Jones D, et al. Frequency and clinical significance of BCR-ABL mutations in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib mesylate. Leukemia. 2006;20(10):1767–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soverini S, Martinelli G, Colarossi S, et al. Presence or the emergence of a F317L BCR-ABL mutation may be associated with resistance to dasatinib in Philadelphia chromosome – positive leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):e51–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, et al. AP24534, a Pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(5):401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jabbour EJ, Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM. Resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibition therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia: a clinical perspective and emerging treatment options. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13(5):515–29. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeFilipp Z, Khoury H. Management of advanced-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10(2):173–81. doi: 10.1007/s11899-015-0249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oyekunle A, Zander AR, Binder M, et al. Outcome of allogeneic SCT in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Ann Hematol. 2013;92(4):487–96. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122:872–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klyuchnikov E, Kröger N, Brummendorf TH, Wiedemann B, Zander AR, Bacher U. Current status and perspectives of tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment in the posttransplant period in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) Biol Blood Marrow Transp. 2010;16(3):301–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirschbuehl K, Rank A, Pfeiffer T, et al. Ponatinib given for advanced leukemia relapse after allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transp. 2015;50(4):599–600. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinwald M, Schleyer E, Kiewe P, et al. Efficacy and pharmacologic data of second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor nilotinib in BCR-ABL-positive leukemia patients with central nervous system relapse after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:637059. doi: 10.1155/2014/637059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasford J, Pfirrmann M, Hehlmann R, et al. A new prognostic score for survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with interferon alfa. Writing Committee for the Collaborative CML Prognostic Factors Project Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(11):850–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes T, Saglio G, Branford S, et al. Impact of baseline BCR-ABL mutations on response to nilotinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(25):4204–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker WT, Ho M, Scott HS, Hughes TP, Branford S. Poor response to second-line kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia patients with multiple low-level mutations, irrespective of their resistance profile. Blood. 2012;119:2234–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soverini S, Gnani A, Colarossi S, et al. Philadelphia-positive patients who already harbor imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl kinase domain mutations have a higher likelihood of developing additional mutations associated with resistance to second- or third-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Blood. 2009;114:2168–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-197186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Jones D, et al. Characteristics and outcome of chronic myeloid leukemia patients with F317L BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation after therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Blood. 2008;112:4839–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faber E, Mojzikova R, Plachy R, et al. Major molecular response achieved with dasatinib in a CML patient with F317L BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation. Leuk Res. 2010;34(4):e91–3. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eşkazan AE, Soysal T. Dasatinib may override F317L BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Turk J Hematol. 2013;30(2):211–3. doi: 10.4274/Tjh.2012.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. http://www.nccn.org.

- 34.O’Brien S, Radich JP, Abboud CN, et al. National comprehensive cancer network Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia, Version 1.2014: Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(11):1327–40. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radujkovic A, Guglielmi C, Bergantini S, et al. Chronic Malignancies Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Donor lymphocyte infusions for chronic myeloid leukemia relapsing after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: may we predict graft-versus-leukemia without graft-versus-host disease? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(7):1230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dazzi F, Fozza C. Disease relapse after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: risk factors and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2007;20(2):311–27. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang H, Xu LP, Liu DH, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic SCT in combination with tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment compared with TKI treatment alone in CML blast crisis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(9):1146–54. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]