Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: clearance, HIV, human papillomavirus, incidence, men who have sex with men

Abstract

Background:

To estimate incidence and clearance of high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV), and their risk factors, in men who have sex with men (MSM) recently infected by HIV in Spain; 2007–2013.

Methods:

Multicenter cohort. HR-HPV infection was determined and genotyped with linear array. Two-state Markov models and Poisson regression were used.

Results:

We analysed 1570 HR-HPV measurements of 612 MSM over 13 608 person-months (p-m) of follow-up. Median (mean) number of measurements was 2 (2.6), median time interval between measurements was 1.1 years (interquartile range: 0.89–1.4). Incidence ranged from 9.0 [95% confidence interval (CI) 6.8–11.8] per 1000 p-m for HPV59 to 15.9 (11.7–21.8) per 1000 p-m for HPV51. HPV16 and HPV18 had slightly above average incidence: 11.9/1000 p-m and 12.8/1000 p-m. HPV16 showed the lowest clearance for both ‘prevalent positive’ (15.7/1000 p-m; 95% CI 12.0–20.5) and ‘incident positive’ infections (22.1/1000 p-m; 95% CI 11.8–41.1). More sexual partners increased HR-HPV incidence, although it was not statistically significant. Age had a strong effect on clearance (P-value < 0.001) due to the elevated rate in MSM under age 25; the effect of HIV-RNA viral load was more gradual, with clearance rate decreasing at higher HIV-RNA viral load (P-value 0.008).

Conclusion:

No large variation in incidence by HR-HPV type was seen. The most common incident types were HPV51, HPV52, HPV31, HPV18 and HPV16. No major variation in clearance by type was observed, with the exception of HPV16 which had the highest persistence and potentially, the strongest oncogenic capacity. Those aged below 25 or with low HIV-RNA- viral load had the highest clearance.

Introduction

The epidemiology of high risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) infection and associated pathologies in HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) has changed profoundly in the last decade [1–3]. The survival gains caused by combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) have been associated with an increase in anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) and anal cancer in MSM, which would have gone unobserved due to competing mortality in the precART era [1–5]. Anal HR-HPV prevalence depends on incidence and persistence of infections. Because HR-HPV persistence increases the risk of AIN [6], understanding its magnitude and risk factors is necessary to develop preventive interventions [5,7–9].

Critchlow et al. reported that HPV incidence was higher in HIV-positive MSM than in HIV-negative ones in Seattle, USA. Unprotected receptive anal intercourse was associated with higher HPV incidence. HPV clearance was lower in HIV-positive MSM and HPV16 and 18 showed higher persistence than HPV31, 33, 35 and 39 [7]. Pokomandy et al. described that, among HIV-positive MSM with long-standing HIV infection (93% on cART) in Montreal, Canada, HPV16 and HPV52 had the highest incidence [10.8 per 1000 person-months (p-m)] whereas HPV16 had the lowest clearance rate (12.2/1000 p-m) [9]. Darwich et al. reported that HPV16 had one of the highest incidences (5.9/1000 p-m) and the lowest clearance rate (18.7/1000 p-m) in HIV-positive MSM in Barcelona, Spain [8]. Phanuphak et al. studied HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM in Bangkok, Thailand, and found HPV16 to have the highest incidence (16.1/1000 p-m) and lower clearance (52/1000 p-m); smoking was associated with increased HR-HPV persistence among HIV-positive MSM [10]. Hernandez et al. described that in HIV-positive MSM enrolled in San Francisco, USA, from 1998–2000, HPV18 and HPV16 had the highest incidence (3.1/1000 p-m and 2.9/1000 p-m) and recent receptive anal intercourse was an important risk factor for incident infection [11].

None of these studies, though, took into account the interval censored nature of the data, that is, that the events of interest (incidence or clearance) are not directly observed. Estimates may be biased downwards if more than one infection and/or clearance episodes had happened between negative and positive test results. Furthermore, these studies (except Hernandez et al. assumed infection and clearance to have happened at the date of sampling [11].

Our aim was to estimate the incidence and clearance rates for type-specific HR-HPV infections as well as type-specific incidence/clearance ratios in MSM recently infected by HIV in a nation-wide study in Spain. Also, we wanted to study risk factors for incidence and clearance for all 12 HR-HPV types.

Methodology

Volunteers and methods

CoRIS-HPV, which has been previously described [12], is a cohort of HIV-positive patients which was set up in 2007 to study HR-HPV infection within CoRIS (Cohort of the Spanish Network of Excellence on HIV/AIDS Research, RIS in Spanish). CoRIS is a multicenter cohort established in January 2004 of individuals with HIV infection and cART naive at entry [13]. Patients in CoRIS are followed periodically according to routine clinical practice, usually every 4 months. Ethics approval has been obtained and participants sign an informed consent for each study.

Within CoRIS-HPV, MSM undergo anal HPV detection and anal cytological examination on a yearly basis, and high-resolution anoscopy when clinically indicated [14]. In addition to socio-demographic, clinical and immuno-virological variables routinely collected at CoRIS [13], study participants also answer a questionnaire on sexual behaviour, history of genital warts and tobacco use. For these analyses, MSM with at least one follow-up HPV test were eligible. Follow-up ended at the last clinic visit and the administrative censoring date was May 2013. Only one follow-up HPV test was required in our definition of infection and clearance.

Human papillomavirus DNA detection and genotyping

Samples for HPV detection were collected from the anal canal with a cytobrush and placed in 1 ml of Specimen Transport Medium (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), stored at –20°C, and shipped to the Retroviruses and Papillomavirus Unit of the National Centre for Microbiology in Madrid. DNA was extracted from a 200-μl aliquot of the original anal sample using an automatic DNA extractor (Biorobot M48 Robotic Workstation; Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). Anal HPV infection and genotyping was determined through the Linear Array HPV Genotyping test (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Pleasanton, California, USA) that detects 37 HPV types. Human β-globin gene fragment detection was used as internal control. The results were considered satisfactory if low and high β-globin levels, or at least one HPV type, were detected. As the linear Array HPV52 probe cross-reacts with HPV33, HPV35 and HPV58, in samples in which either of these HPV types were detected a specific HPV52 PCR system designed in E6 gene was performed [15]. A more detailed description of virological methods has been published [16]. Twelve HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58 and 59) were considered as HR-HPV types following the classification by Muñoz et al[17].

Statistical analysis

Because the information on HPV status that is collected at the visits may not be sufficient to describe the dynamics of infection and clearance, particularly when test interval is 12 months such as in our study, we estimated incidence and clearance rates using a two-stage Markov model that allowed for interval censored event data. In the Markov model individuals can switch between states ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ at rates λinf (negative to positive) for incident infection and λclear (positive to negative) for clearance. The Markov assumption entails that the rate only depends on the current state; history of past HPV infection is not taken into account. Markov models can be defined by means of transition probabilities; an equivalent infinitesimal definition is based on the transition hazards, which is what we used. Both incidence and clearance rates were estimated jointly by maximizing the likelihood of the observed data, taking into account its interval censored nature. This likelihood takes the data as they are, that is, it only uses the information on HR-HPV infection status at the times of sample collection, but individuals can switch between both states at any time point, not just at the time of testing. As a consequence, we allow several infections and clearances to occur between two samples. Fitting Markov models with interval censored data has been described in detail [18].

We estimated incidence and clearance rate for each HPV type separately, assuming a constant rate over time. Incidence and clearance rates are expressed as events per 1000 person-months (p-m). Ratios of infection and clearance were estimated as well. Sampling uncertainty is expressed via 95% confidence intervals (CI).

For clearance rates, one constant value would not be appropriate if there were a group with high clearance and another group with low clearance rates. Therefore, we included a covariable that makes a distinction between clearance after an HPV positive visit at entry (prevalent positive cases) and clearance after an observed new infection (incident positive cases). This covariable was modelled as time-dependent: once a ‘prevalent positive’ person had cleared HPV and got re-infected, he contributed to the estimate of the ‘incident positive’ group after reinfection. These data, however, do not allow distinguishing reinfection from reactivation.

In risk factor analyses, we allowed age, CD4+ T-cell counts, HIV-RNA viral load and cART to affect both transition rates. The incidence rate was additionally allowed to depend on number of male sexual partners, consistent condom use with anal sex in the last 12 months and country of origin. Clearance was allowed to depend on variables that were different to those for incidence, as conceptualized from the literature: current smoking status, educational level and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stage [19]. First, we did the analysis per HR-HPV type, in which we assumed effects on the logarithm of the rate to be linear for age, square-root of CD4+ cell count, the base-10 logarithm of HIV-RNA viral load and the base-2 logarithm of number of sexual partners. We quantified their effects using the same Markov model that we used for the overall incidence calculations. For the reasons given below, we used and compared results with a Poisson regression model, again assuming a constant rate over time. In this model, we followed individuals until the first event and assumed that there were no unobserved events before. Since detection times cannot be equated to incidence or clearance dates, we took the midpoint of the time between two measurements to define incidence or clearance.

We informally compared results from both regression models in order to see whether we could use the Poisson model when fitting a model for all types jointly. In this model, the effect of the risk factors was assumed equal for all types, but we allowed overall rates (the intercepts) to differ by HPV type [20]. For this model, we did not have software that both allows for interval censored transitions in a Markov model and correlation induced by considering all HR-HPV types in one model. In this combined Poisson model, we used generalized estimating equations to correct for multiple HPV types, assuming an exchangeable correlation structure. By assuming effects to be equal, we gained enough power to increase flexibility and allow the effects of continuous variables to be nonlinear; we used restricted cubic splines (four knots for age and three knots for the other variables).

Missing data were imputed using MICE (multiple imputation using chained equations) [21]. The proportion of missing data was low (Table 1). Ten imputed datasets were generated. The time-varying variables CD4+ cell count (on square root scale) and HIV-RNA viral load (on fourth root scale) were imputed based on a longitudinal mixed effects model for the development of the respective markers. The same was done for the base-2 logarithm of the number of partners over the last 12 months and condom use during anal sex. After the imputation procedure, all values beyond the range were cut off to the smallest and the largest value. We compared results with and without MICE.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 612 HIV-positive MSM from CoRIS-HPV cohort study.

| No. (%) | |

| Age | |

| Median (IQR) | 33.0 (28.1–39.1) |

| Country of origin | |

| Europe | 459 (75) |

| Other | 153 (25) |

| Educational level | |

| Less than or equal to secondary school | 331 (54.1) |

| University | 280 (45.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) |

| Tobacco use | |

| Current smoker | 270 (44.1) |

| No smoker | 325 (53.1) |

| Missing | 17 (2.8) |

| Number of sexual partners in last 12 months | |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (2–20) |

| Missing | 59 (9.6) |

| Unprotected anal intercourse in the last 12 months | |

| No | 196 (32.2) |

| Yes | 399 (64.7) |

| Missing | 17 (3.1) |

| CDC stage at baseline | |

| Primary infections/asymptomatic | 570 (93.1) |

| Symptomatic/AIDS | 42 (6.9) |

| cART at baseline | |

| No | 374 (61) |

| Yes | 238 (39) |

| CD4+ cell count at baseline (cells/μl) | |

| Median (IQR) | 569 (444–741) |

| Missing | 3 (0.5) |

| HIV RNA Viral Load at baseline (log10 copies/ml) | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.1 (3.1–4.6) |

| Missing | 3 (0.5) |

cART, combination antirretroviral therapy; IQR, Interquartile range.

Analyses were conducted in R version 3.0.2 [22].

Results

Of 1476 HIV-positive MSM within CoRIS-HPV, 612 had at least two visits; characteristics of these 612 men did not differ substantially from the other 864 (data not shown). Of the 603 men with information on HPV status at study entry, 500 (83%) were infected with at least one HR-HPV type. There were 1570 measurements over 13 608 p-m follow-up. The median (mean) number of measurements per individual was two (2.6) and the median time interval between measurements was 1.1 years [interquartile range (IQR): 0.89–1.4]. Median age at entry was 33 years (IQR: 28–39), 75% were European (95% of them Spanish) and of the remaining 153, 91% were Latin-Americans. Median number of sexual partners in the preceding 12 months was six (IQR: 2–20) and 65% reported unprotected anal intercourse in the previous year. Median baseline CD4+ cell count was 569 cells/μl (IQR: 444–741), median log10 HIV-RNA viral load was 4.1 (IQR: 3.1–4.6) and 61% were cART naive at baseline; four started cART during follow-up (Table 1).

Incidence, clearance and incidence/clearance ratios for individual HR-HPV types

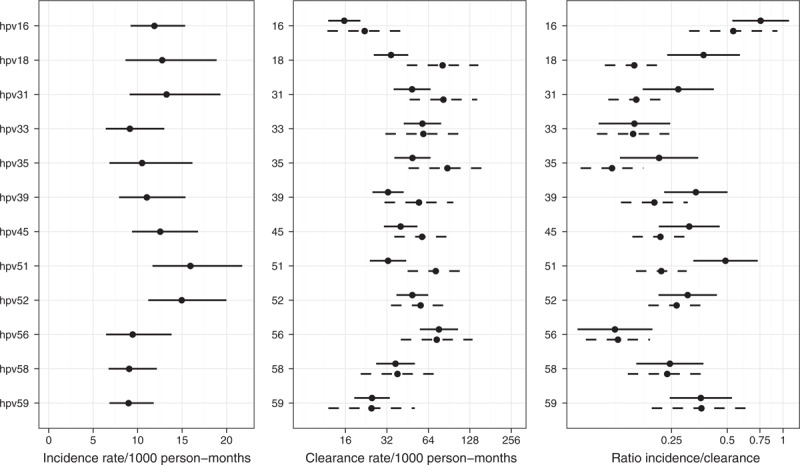

Incidence and clearance rates for each HR-HPV type are plotted in Fig. 1. Incidence as estimated by the Markov model ranged from 9.0/1000 p-m (95% CI 6.8–11.8) for HPV59 to 15.9/1000 p-m (95% CI 11.7–21.8) for HPV51. HPV16 and HPV18 had an average and slightly above average incidence respectively [11.9/1000 p-m (95% CI 9.20–15.3) and 12.8/1000 p-m (95% CI 8.6–18.9)] (Fig. 1). Clearance rates showed more variability; HPV16 showed the lowest clearance for both ‘prevalent positive’ (15.7/1000 p-m 95% CI 12.0–20.5) and ‘incident positive’ infections (22.1/1000 p-m 95% CI 11.8–41.1) (Fig. 1). For most HR-HPV types, ‘incident positive’ infections had higher clearance than ‘prevalent positive’ infections. The relatively high incidence and the low clearance rate together made HPV16 stand out as the genotype with the highest incidence/clearance ratio, both when using clearance from ‘prevalent positive’ infections [0.76; (95% CI 0.53–1.08)] and ‘incident positive’ infections [0.54; 95% CI 0.31–0.93)] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Incidence rates, clearance rates and incidence/clearance ratios with 95% CI, based on the two-state Markov model.

Dashed lines in clearance rate and ratio are based on the ‘incident HR-HPV infections’, solid lines on ‘prevalent HR-HPV infections’.

Risk factors for incidence and clearance of HR-HPV

In the regression models per HR-HPV type, there were few statistically significant effects, neither on the incidence, nor on the clearance rate (Appendix Figure 1). Effects were fairly consistent over the HR-HPV types. Furthermore, the Markov and Poisson models showed comparable results, which justified the use of the Poisson model as an approximation in the combined analyses over all HR-HPV types.

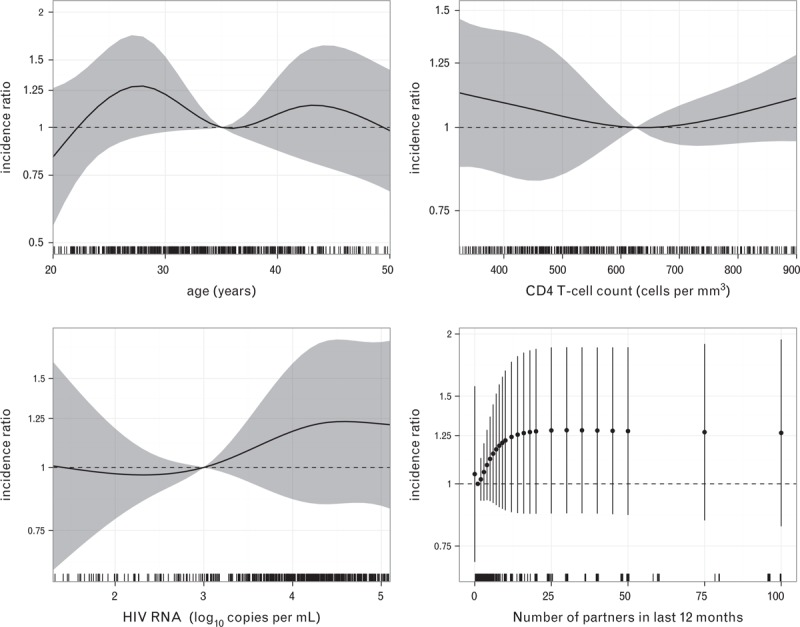

In the combined analysis, none of the variables had a statistically significant effect on HR-HPV incidence; P-values for the effect of age, CD4+ cell count and HIV-RNA viral load were 0.17, 0.49 and 0.55, respectively (Fig. 2). Although not significant (P = 0.31), increasing HR-HPV incidence was observed with increasing numbers of sexual partners in the preceding year. MSM with 10 sexual partners in the last year had an incidence that was 1.22 (95% CI 0.88–1.69) times higher than those who had one partner; beyond 15 partners the effect levelled off. The relative incidence of the other three covariables were: UAI 1.17 (95% CI 0.92–1.48; P = 0.18); non-European country of origin 1.03 (95% CI 0.81–1.30; P = 0.91); cART naïve 1.01 (95% CI 0.79–1.29; P = 0.90). Figure 2 provides the incidence ratios for the effect of age (relative to 35 years), CD4+ cell count (relative to 625 cells/μl), HIV RNA viral load (relative to 1000 copies/ml) and number of sexual partners in the last 12 months (relative to one partner).

Fig. 2.

Rate ratios (RRs) for the effect of age (relative to 35 years), CD4+ cell count (relative to 625 cells/μl), HIV RNA viral load (relative to 1000 copies/ml) and number of sexual partners in the last 12 months (relative to one partner) on HR-HPV incidence (all 12 types together).

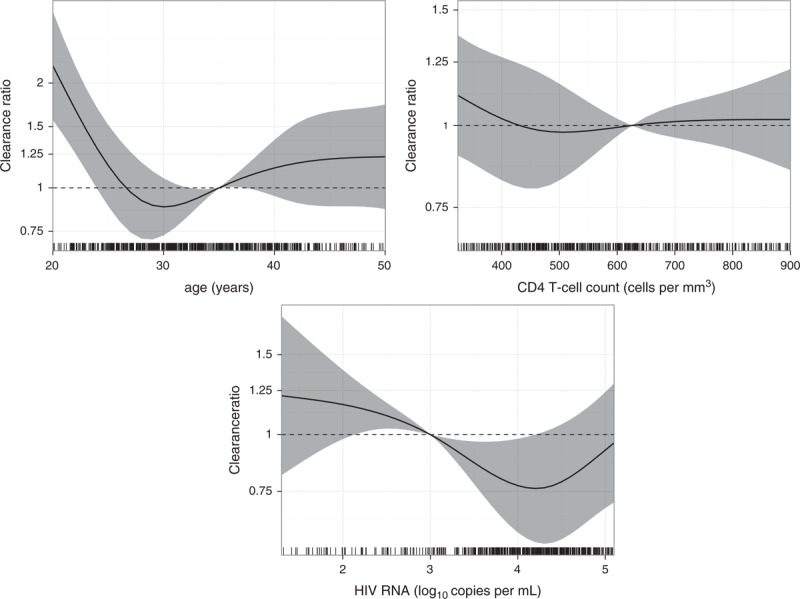

Age and HIV-RNA viral load had a statistically significant effect on HR-HPV clearance (P < 0.001 and 0.008, respectively). Age showed a distinctive nonlinear effect (Fig. 3); the highest clearance rate was found in MSM under age 25, whereas MSM around 30 seemed to have the lowest clearance rate. For HIV-RNA viral load there was a trend with lower HR-HPV clearance rates for those with higher HIV-RNA viral load. No statistically significant effect was observed for CD4+ cell count (P = 0.42). University education, asymptomatic stage and not using cART increased clearance rates by 1.15 (95% CI 0.96–1.34; P = 0.13), 1.06 (95% CI: 0.70–1.59; P = 0.78) and 1.23 (95% CI: 0.98–1.55; P = 0.07).

Fig. 3.

Rate ratios (RRs) for the effect of age (relative to 35 years), CD4+ cell count (relative to 625 cells/μl), HIV RNA viral load (relative to 1000 copies/ml) on HR-HPV clearance (all 12 HR-HPV types together).

Discussion

In MSM recently infected by HIV in a contemporary multicenter cohort in Spain, the highest HR-HPV incidence was observed for HPV51 and 52 followed by HPV31, HPV18, HPV45 and HPV16. HPV16 had the lowest clearance rate and the largest incidence/clearance ratio, especially in the individuals that were already HPV-infected at entry, and thus potentially the highest oncogenic capacity. In the analyses of effects of covariables on incidence and clearance of the 12 HR-HPV types together, none of the risk factors for HR-HPV incidence yielded statistically significant results. For HR-HPV clearance, age and plasma HIV-RNA viral load revealed significant effects; a strongly nonlinear effect of age was observed as HIV-positive MSM younger than 25 years had up to twice the clearance of older ones. Men with higher plasma HIV-RNA viral load had lower HR-HPV clearance.

Our estimates for HR-HPV incidence are larger than those reported by most other authors [8–11]. Clearance rates are also higher except for the study by Phanuphak et al.[10]. Direct comparisons are hampered by differences in sample characteristics (age distribution, maturity of HIV infection), width of follow-up intervals, and number of follow-up samples to define outcomes. Incidence and clearance rates were defined based on single HPV determinations in a follow-up visit. Some authors have used two successive six monthly HPV negative tests to define clearance in HIV-negative populations [11,23]. Given our study was designed to have yearly HPV determinations, requesting a second confirmatory test would have required to wait for as long as two years before establishing outcomes and could therefore have introduced other sources of misclassification. Some of the differences between our results and other authors’ may also be related to the incorporation of the interval censored information. Our two-state Markov model makes allowance for unobserved re-infections between visits. When we used standard person-years calculations for overall incidence and clearance rate and equated time of diagnosis to time of event occurrence, incidence estimates decreased by 22% for HPV16 to 53% for HPV56, and clearance decreased between 22% for HPV16 and 42% for HPV51.

HR-HPV persistence of ‘prevalent cases’, that is, individuals already HR-HPV positive at entry was higher than that of ‘incident cases’ suggesting prevalent cases partly encompass long-standing infections which are, most likely, the ones leading to aberrant epithelial transformations.

Our group has recently reported that the number of HR-HPV types in the anal canal in HIV-positive MSM is driven by recent sexual behaviour and age, with peak prevalence around the age of 35 [12]. In these new and longitudinal analyses, we provide more in-depth understanding of our previous findings as we have found that age had little to no relation to incidence but individuals of younger age had higher HR-HPV clearance. To our knowledge, no other study in HIV-positive MSM has identified this age effect. The direction of the association between age and clearance described by Giuliano et al. in samples from the coronal sulcus, glans penis, shaft, and scrotum from HIV-negative men was in opposite direction; HR-HPV clearance increased with age [23]. They attribute this pattern to the higher prevalence of HPV antibodies in older men and thus antibody-mediated acquired immunity. Nyitray et al. did not find an association between HPV clearance and age in HIV-negative MSM, whereas they report decreasing HPV clearance with increasing age in men who have sex with women [24]. A larger number of sexual partners in the preceding 12 months showed a suggestive but not statistically significant trend towards higher HR-HPV incidence, consistent with what has been described for HIV-negative men [23].

We did not find an effect of CD4+ cell count on HR-HPV clearance. However, individuals with high HIV-RNA viral load had lower HR-HPV clearance. Uncontrolled HIV infection may increase HR-HPV persistence through altered cell-mediated immunity, local molecular interactions and reduced tight junction function [25–27]. This effect has not been previously described in HIV positive MSM. Kang et al. described lower HR-HPV clearance in HIV-positive women with high HIV-RNA viral load. In-vitro studies show increased expression of HPV E1 and L1 viral genes in the presence of HIV transactivator of transcription (tat) proteins [28]. During HPV replication, HIV-tat protein was shown to enhance HPV transcription [29–31]. The immune response to chronic viral infections is polyfunctional type 1 of both CD4+ helper T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic cells [32]. The lack of a clear relationship between CD4+ cell counts and HR-HPV clearance in HIV-positive MSM has been reported by Phanuphak et al.[10]. Critchlow et al. reported weak associations between CD4+ cell count and HR-HPV persistence [7] but none was found by Pokomandy and Darwich [8,9]. Studies conducted in other HIV-positive populations besides MSM did neither show an association between HPV clearance and CD4+ cell count [33].

Our results contribute to the scarce body of literature on natural history of anal HR-HPV infection in HIV-positive MSM, particularly in those recently infected by HIV, by providing estimates on incidence and persistence of HR-HPV infection, as well as risk factors.

Acknowledgements

Authors and contributors: C.G., M.T., J.d.R., P.V., M.M., J.R.B., M.I., S.d.S., B.H-N., M.O. and J.d.A. were involved in the setting up of the cohort and conceptualized the design. J.d.A., M.O., C.G. and R.G. asked the research question. R.G. was responsible for statistical analyses. C.G., M.T., J.D.R., P.V., M.M., J.R.B., M.I., B.H-N. were involved in data collection. Laboratory analyses were performed by M.T. and M.O. The study was coordinated by C.G., C.G., R.G. and J.d.A. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors were involved in interpretation of the data and commented interim drafts. All authors have reviewed the final manuscript.

Meetings and Conferences: No presentations.

CoRIS-HPV Study Group

CoRIS-HPV group participating centres and members are as follows: at the Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Granada—Alejandro Peña and Federico García; Centro Nacional de Microbiología (ISCIII), Madrid— Marta Ortiz and Montserrat Torres; Hospital Xeral, Vigo—Antonio Ocampo,Alfredo Rodriguez Da Silva, Celia Miralles, Gustavo Mauricio Iribarren, and Joaquín González-Carreró; Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal-IRYCIS, Madrid—Beatriz Hernández-Novoa, Nadia Madrid, Amparo Benito and Itziar Sanz; Centro Sanitario Sandoval, Madrid— Jorge del Romero, Mar Vera, Carmen Rodríguez, Teresa Puerta, Juan Carlos Carrió, and Montserrat Raposo; Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville—Pompeyo Viciana, Mónica Trastoy, and Maria Fontillón; Hospital Universitario de Elche, Alicante—Mar Masiá, Catalina Robledano, Félix Gutierrez, Sergio Padilla, and Encarna Andrada; Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Madrid—Miguel Cervero; Hospital San Pedro-CIBIR, La Rioja—José Ramón Blanco and Laura Pérez; Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Alicante—Joaquín Portilla and Irene Portilla; Hospital Universitario Donostia, San Sebastián—Miguel Ángel Vonwichmann, Jose Antonio Iribarren, and Xabier Camino; Hospital Universitario La Paz-IdiPAZ, Madrid—Elena Sendagorta and Pedro Herranz; Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife—Patricia Rodríguez, Juan Luis Gómez, and Dacil Rosado; Centro Nacional de Epidemiología (ISCIII), Madrid—Julia del Amo, Cristina González, M. Ángeles Rodríguez-Arenas, Belén Alejos, and Paz Sobrino-Vegas; and Institut Català d’Oncologia, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat—Silvia de Sanjosé.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria [PI06/0372, PS09/2181], Red de Investigación en SIDA (RIS) [RD06/006/0026 and RD12/0017/0018 to C.G.] and CIBERESP [group 54A-CB06/02/1009].

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (http://www.AIDSonline.com).

References

- 1.Bertisch B, Franceschi S, Lise M, Vernazza P, Keiser O, Schoni-Affolter F, et al. Risk factors for anal cancer in persons infected with HIV: a nested case-control study in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178:877–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piketty C, Cochand-Priollet B, Lanoy E, Si-Mohamed A, Trabelsi S, Tubiana R, et al. Lack of regression of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions despite immune restoration under cART. AIDS 2013; 27:401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Justice AC, Engels E, Gill MJ, Goedert JJ, et al. Risk of anal cancer in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1026–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Souza G, Wiley DJ, Li X, Chmiel JS, Margolick JB, Cranston RD, et al. Incidence and epidemiology of anal cancer in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 48:491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F, Fairley CK, Farnsworth A, Garland SM, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13:487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Wurscher MA, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer 2004; 101:270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Critchlow CW, Hawes SE, Kuypers JM, Goldbaum GM, Holmes KK, Surawicz CM, et al. Effect of HIV infection on the natural history of anal human papillomavirus infection. AIDS 1998; 12:1177–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darwich L, Canadas MP, Videla S, Coll J, Molina-Lopez RA, Sirera G, et al. Prevalence, clearance, and incidence of human papillomavirus type-specific infection at the anal and penile site of HIV-infected men. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40:611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Pokomandy A, Rouleau D, Ghattas G, Vezina S, Cote P, Macleod J, et al. Prevalence, clearance, and incidence of anal human papillomavirus infection in HIV-infected men: the HIPVIRG cohort study. J Infect Dis 2009; 199:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phanuphak N, Teeratakulpisarn N, Pankam T, Kerr SJ, Barisri J, Deesua A, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection among Thai men who have sex with men with and without HIV infection: prevalence, incidence, and persistence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63:472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez AL, Efird JT, Holly EA, Berry JM, Jay N, Palefsky JM. Incidence of and risk factors for type-specific anal human papillomavirus infection among HIV-positive MSM. AIDS 2014; 28:1341–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.del Amo J, Gonzalez C, Geskus RB, Torres M, Del RJ, Viciana P, et al. What drives the number of high-risk human papillomavirus types in the anal canal in HIV-positive men who have sex with men?. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobrino-Vegas P, Gutierrez F, Berenguer J, Labarga P, Garcia F, Alejos-Ferreras B, et al. The Cohort of the Spanish HIV Research Network (CoRIS) and its associated biobank; organizational issues, main findings and losses to follow-up. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2011; 29:645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González C, Torres M, Benito A, Del RJ, Rodriguez C, Fontillon M, et al. Anal squamous intraepithelial lesions are frequent among young HIV-infected men who have sex with men followed up at the Spanish AIDS Research Network Cohort (CoRIS-HPV). Int J Cancer 2013; 133:1164–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aho J, Hankins C, Tremblay C, Forest P, Pourreaux K, Rouah F, et al. Genomic polymorphism of human papillomavirus type 52 predisposes toward persistent infection in sexually active women. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres M, Gonzalez C, Del RJ, Viciana P, Ocampo A, Rodriguez-Fortunez P, et al. Anal human papillomavirus genotype distribution in HIV-infected men who have sex with men by geographical origin, age, and cytological status in a Spanish cohort. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:3512–3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz N, Castellsague X, de Gonzalez AB, Gissmann L. Chapter 1: HPV in the etiology of human cancer. Vaccine 2006; 24 Suppl 3:S3/1-10 Epub;%2006 Jun 23:S3-1-S310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson CH. Multi-state models for panel data: the msm package for R. J Stat Softw 2011; 38:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ancelle-Park R. Expanded European AIDS case definition. Lancet 1993; 341:441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue X, Gange SJ, Zhong Y, Burk RD, Minkoff H, Massad LS, et al. Marginal and mixed-effects models in the analysis of human papillomavirus natural history data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19:159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Buuren S. Flexible imputation of missing data. Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Ratón, FL; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011, [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, Villa LL, Lazcano E, Papenfuss MR, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. Lancet 2011; 377:932–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyitray AG, Carvalho da Silva RJ, Baggio ML, Smith D, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss M, et al. Six-month incidence, persistence, and factors associated with persistence of anal human papillomavirus in men: the HPV in men study. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:1711–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palefsky JM. HPV infection in the HIV-positive host: molecular interactions and clinical implications. Proceedings of the Lancet Conference, HPV and Cancer, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, November 2010; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott M, Nakagawa M, Moscicki AB. Cell-mediated immune response to human papillomavirus infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001; 8:209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tugizov SM, Herrera R, Chin-Hong P, Veluppillai P, Greenspan D, Michael BJ, et al. HIV-associated disruption of mucosal epithelium facilitates paracellular penetration by human papillomavirus. Virology 2013; 446 (1–2):378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang M, Cu-Uvin S. Association of HIV viral load and CD4 cell count with human papillomavirus detection and clearance in HIV-infected women initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2012; 13:372–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolei A, Curreli S, Marongiu P, Pierangeli A, Gomes E, Bucci M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in vitro activates naturally integrated human papillomavirus type 18 and induces synthesis of the L1 capsid protein. J Gen Virol 1999; 80 (Pt 11):2937–2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tornesello ML, Buonaguro FM, Beth-Giraldo E, Giraldo G. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat gene enhances human papillomavirus early gene expression. Intervirology 1993; 36:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vernon SD, Hart CE, Reeves WC, Icenogle JP. The HIV-1 tat protein enhances E2-dependent human papillomavirus 16 transcription. Virus Res 1993; 27:133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zajac AJ, Murali-Krishna K, Blattman JN, Ahmed R. Therapeutic vaccination against chronic viral infection: the importance of cooperation between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Curr Opin Immunol 1998; 10:444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beachler DC, D'Souza G, Sugar EA, Xiao W, Gillison ML. Natural history of anal vs oral HPV infection in HIV-infected men and women. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.