Abstract

Objectives

The older adult population in the United States (U.S.) uses multiple medications and more than half of older adults drink alcohol regularly. In addition, older adults are more likely to experience adverse effects of medications and alcohol consumption may put them at higher risk. Our primary objective is to characterize the extent and nature of drug-alcohol interactions among older adults in the U.S.

Design, Setting, Participants, Measurements

We used a nationally-representative population-based sample of community-dwelling older adults in the U.S. Regular drinkers were defined as respondents that consumed alcohol at least weekly. Medication use was defined as the use of a prescription or non-prescription medication or dietary supplement at least daily or weekly. Micromedex was used to determine drug interactions with alcohol and their corresponding severity.

Results

Among the 2,975 older adults in the sample, more than 41% (N=1106) consume alcohol regularly and more than 20% (N=567) are at-risk for a drug-alcohol interaction because they are regular drinkers and concurrently using alcohol interacting medications. More than 90% of these interactions were of moderate or major severity. Antidepressants and analgesics were the most commonly used alcohol-interacting medications among regular drinkers. Older adult men with multiple chronic conditions had the highest prevalence of potential drug-alcohol interactions.

Conclusion

The potential for drug-alcohol interactions among the older adult population in the U.S. may have important clinical implications. Efforts to better understand and prevent the use of alcohol-interacting medications among regular drinkers, particularly heavy drinkers, are warranted in this population.

Keywords: Aging, Prescription Drug Abuse and Misuse

BACKGROUND

The vast majority of older adults in the U.S. use prescription and non-prescription medications,1 and more than 50% drink alcohol regularly.2 Older adults are also more likely to suffer from chronic conditions and to experience the adverse effects of both medications3 and alcohol use.4 Many medications commonly used among older adults such as analgesics, sedatives, and antidepressants, interact with alcohol and further increase the risk for adverse drug events including falls, automobile accidents and death. 5,6 Older adults that drink alcohol regularly are more likely to be admitted for an adverse drug event,4 with more than 25% of emergency room admissions associated with a drug-alcohol interactions.7 Despite this, nationally-representative information on the prevalence of drug-alcohol interactions in the U.S. older adult population is limited.

Previous studies examining drug-alcohol interactions in the U.S. do not focus on older adults and are limited to prescription medications.8,9 A study conducted in 2008 using data from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) reports that approximately 13.5% of adults 20 years and older were using an alcohol-interacting prescription medication of which 6% were at high risk for a alcohol-related adverse-event.8 Further, a study derived from pharmacy-claims and survey data among low-income beneficiaries of the Pennsylvania Pharmaceutical Assistance Program reports 20% of adults 65 years and older are potentially at risk for drug-alcohol interactions.9 However, this study is not nationally-representative and excludes information on non-prescription medications.

In the current study, we use data from the National, Social life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), a population-based survey of community-dwelling older adults in the United States. Our primary objective is to examine the prevalence of drug-alcohol interactions among older adults in the U.S. overall and by therapeutic classes of prescription and non-prescription medications, and identify older adult individuals most at-risk for such use.

METHODS

Subjects

The NSHAP is a nationally representative probability sample of community-dwelling persons 57 to 84 years of age (at the time of screening in 2004) from households across the United States. Blacks, Hispanics, men, and the oldest persons (75 to 84 years of age at the time of screening) were oversampled. Of 4017 eligible persons, 3005 were successfully interviewed, yielding an unweighted response rate of 74.8% and a weighted response rate of 75.5%. Professional interviewers conducted in-home interviews and compiled medication logs in English and Spanish between July 2005 and March 2006. NSHAP is sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the study protocol has been previously described.1 The University of Chicago and NORC institutional review boards approved the NSHAP protocol, and all respondents provided written informed consent.

Data

Data on medication use were collected during the household interview by direct observation of medication bottles using a computer-based log. Participants were asked to provide the interviewer with all medications used “on a regular schedule, like every day or every week” and were instructed to include “prescription and non-prescription medications, over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and herbal and alternative medicines.” All identifiable drug names for prescription and over-the-counter medications, and dietary supplements were coded. Additional details on the method of drug coding have been previously described.10

We used Thomson Micromedex®11 to identify alcohol interacting medications. Micromedex® also provided a measure of the severity of the interaction (contraindicated—the drugs are contraindicated for use; major—the interaction may be life-threatening and/or require medical intervention to minimize or prevent serious adverse events; moderate—the interaction may result in the exacerbation of the patient’s condition and/or require an alternation in therapy; minor—the interaction would have limited clinical effects).

We defined drinking characteristics based on responses to a series of questions: “Do you ever drink any alcohol beverages such as beer, wine, or liquor?”; “In the past three months, on average, how many days per week have you had any alcohol to drink (for example, beer, wine, or liquor)?”; and “How many drinks do you have on the days that you drink?”. Non-regular drinkers were those respondents that did not drink alcohol or drink less one day per week. Regular drinkers are respondents that drink at least one day per week. We further characterized regular drinkers into three categories based on the frequency of drinking on drinking days: light drinkers (1-drink per day); heavy drinkers (2–3 drinks per day); and binge drinkers (4 or more drinks per day). These definitions have been previously used to define drinking behavior in older adults.2,4 We defined respondents with the potential of a drug-alcohol interaction as those that were regular drinkers and using at least one alcohol-interacting medication with any level of interaction severity.

We used the following age intervals: 57–64 years, 65–74 years, and 75–85 years (some individuals originally 84 years at the time of interview had turned 85). We defined race and ethnicity as a four category variable: white or Caucasian, black or African American, Hispanic non-black, and other. Additionally, level of education was defined into four categories: less than high school education, high school graduate or GED completion, some college or vocational education (associate degree included), and a bachelor’s degree or higher. Lastly, we defined income into four categories using the question “Approximately what was the income of your household last year (this year minus one) before taxes or deductions”. The four income-related categories were <$25,000, $25,000–$50,000, <$50,000–$74,999, and ≥ $75,000.

We also considered healthcare and health-related factors as important considerations in our study. Information about insurance status was ascertained by asking the question “Are you currently covered by any of the following health insurance programs (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, Veterans Administration, or other)”. Participants that did not report being covered by any of these programs (including “other”) were considered to have no insurance.

We included a measure of self-reported health where respondents had to qualify their physical health into a standard 5-point scale with responses poor, fair, good, very good, and excellent. Additionally, we included a measure of comorbidity as concurrent health conditions can impact drug-alcohol interactions. We calculated a comorbidity index based on a previously validated algorithm used in questionnaire and survey research.12 This comorbidity index was based on respondent responses to whether or not they had the following health conditions: myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, peptic ulcer disease/stomach ulcers, arthritis, emphysema/COPD, stroke, diabetes, dementia or Alzheimer’s, cirrhosis, leukemia, lymphoma, poor kidney function, and cancer that has/not spread.

Analysis

For each analysis, we used weights included in the National, Social life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) dataset to adjust for oversampling, differential probability of selection, and differential non-response.13 Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the prevalence of drug-alcohol interactions (overall and by drinking frequency) among the entire sample and stratified by age and gender. The chi-square statistic was used to test statistical significance at the 0.05 level. We used logistic regression to assess which variables were significantly (p<0.05) associated with a potential drug-alcohol interaction. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents older adult socio-demographic and health characteristics overall and by drinking status. During 2005 to 2006, 41% of older adults were regular drinkers of alcohol (at least 1 drink every week). The prevalence of regular drinking was more common in older adult men, 57–64 years and Whites as well as those with higher income, education and excellent self-reported health. Further, older adults that are regular drinkers are significantly (p<0.05) less likely to use alcohol-interacting medications. Seventeen percent of older adults are light drinkers (at least 1 drink/day), while 20% are moderate drinkers (2–3 drinks/day) and less than 5% are considered heavy/binge (≥4 drinks/day) drinkers. Across all age groups women are significantly (p<0.05) less likely to drink alcohol regularly in comparison to men. Further, among those that drink, across all age groups, women are significantly more likely to be light drinkers. (Appendix)

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics Overall and by Drinking Status (N=2975)

| Overall (N=2975) | Regular Drinkers (at least 1 day/week) (N=1106) | Non-regular Drinkers (<1 day/week) (N=1869) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=2975) | 100 | 40.9 (37.8–44.0) | 59.1 (56.0–62.2) |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male (N=1445) | 48.6 (46.2–51.0) | 59.3 (55.9–62.8)* | 41.2 (38.2–44.2) |

|

| |||

| Women (N=1530) | 51.4 (49.0–53.8) | 40.7 (37.2–44.1) | 58.8 (55.8–61.8) |

|

| |||

| Age, y | |||

| 57–64 (N=1015) | 41.5 (39.0–44.0) | 45.1 (41.2–49.0)* | 39.0 (36.1–41.9) |

|

| |||

| 65–74 (N=1082) | 34.9 (32.7–37.1) | 36.1 (32.6–39.7) | 34.0 (31.1–36.9) |

|

| |||

| 75–85 (N=878) | 23.6 (21.7–25.6) | 18.8 (15.7–21.9) | 27.0 (24.6–29.4) |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic (N=2091) | 80.7 (77.0–84.4) | 86.0 (82.9–89.0)* | 77.1 (72.3–81.9) |

|

| |||

| Black, non-Hispanic (N=500) | 9.9 (7.6–12.2) | 6.6 (4.2–9.0) | 12.2 (9.3–15.1) |

|

| |||

| Hispanic, any race (N=302) | 6.9 (3.5–10.2) | 5.3 (3.6–7.1) | 7.9 (3.2–12.7) |

|

| |||

| Other (N=70) | 2.5 (1.6–3.4) | 2.1 (1.1–3.1) | 2.8 (1.6–3.9) |

|

| |||

| Income, $ | |||

| <25,000 (N=759) | 29.3 (25.1–33.5) | 17.1 (13.8–20.3)* | 39.1 (34.0–44.2) |

|

| |||

| 25,000–50,000 (N=697) | 34.5 (31.3–37.6) | 35.4 (30.3–40.6) | 33.7 (30.0–37.3) |

|

| |||

| >50,000–74,999 (N=237) | 12.9 (10.8–14.9) | 14.5 (10.6–18.3) | 11.6 (9.2–13.9) |

|

| |||

| ≥75,000 (N=422) | 23.4 (19.6–27.2) | 33.0 (27.5–38.6) | 15.6 (12.6–18.7) |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| <HS (689) | 18.4 (15.2–21.7) | 11.1 (8.4–13.7)* | 23.5 (19.5–27.5) |

|

| |||

| HS graduate/GED (N=784) | 26.9 (24.4–29.4) | 22.3 (18.7–25.8) | 30.1 (26.9–33.3) |

|

| |||

| Some college/AA/Voc. (N=849) | 30.1 (27.3–32.9) | 31.8 (28.3–35.3) | 28.9 (25.4–32.3) |

|

| |||

| Bachelors or Above (N=653) | 24.6 (21.3–27.9) | 34.9 (30.4–39.4) | 17.5 (14.9–20.1) |

|

| |||

| Self-Reported Health | |||

| Poor (N=219) | 6.7 (5.4–8.1) | 4.2 (2.3–6.0)* | 8.5 (7.2–9.9) |

|

| |||

| Fair (N=574) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 13.7 (11.0–16.4) | 20.9 (18.4–23.4) |

|

| |||

| Good (N=899) | 29.6 (27.5–31.6) | 26.3 (23.6–29.0) | 31.8 (28.9–34.8) |

|

| |||

| Very Good (N=912) | 32.6 (30.5–34.7) | 36.9 (33.7–40.1) | 29.7 (27.0–32.3) |

|

| |||

| Excellent (N=360) | 13.1 (11.3–14.9) | 18.9 (15.7–22.1) | 9.1 (7.2–10.9) |

|

| |||

| Insurance Coverage | |||

| None (N=146) | 5.1 (3.9–6.3) | 4.3 (2.8–5.8)* | 5.7 (3.9–7.5) |

|

| |||

| Medicare (N=1565) | 57.8 (54.8–60.8) | 53.7 (49.1–58.3)* | 60.8 (57.4–64.1) |

|

| |||

| Medicaid (N=186) | 5.8 (4.2–7.4) | 3.8 (2.4–5.1)* | 7.3 (5.1–9.5) |

|

| |||

| Private Insurance (N=1410) | 61.8 (58.0–65.6) | 70.2 (66.2–74.3)* | 55.6 (50.7–60.5) |

|

| |||

| VA(N=174) | 6.9 (5.5–8.4) | 7.4 (5.1–9.7) | 6.6 (5.1–8.1) |

|

| |||

| Other (N=305) | 12.2 (10.7–13.6) | 10.7 (8.2–13.2) | 13.2 (11.0–15.3) |

|

| |||

| Co-Morbidity | |||

| 0 (N=706) | 24.7 (22.9–26.4) | 31.0 (27.7–34.4)* | 20.3 (18.2–22.3) |

|

| |||

| 1–4 (N=2050) | 68.8 (66.8–70.8) | 64.3 (60.5–68.1) | 71.9 (69.5–74.2) |

|

| |||

| 5+ (N=219) | 6.6 (5.5–7.7) | 4.7 (3.3–6.1) | 7.9 (6.4–9.3) |

|

| |||

| Use Prescription Medications (N=2454) | 81.4 (79.3–83.5) | 77.3 (74.4–80.2)* | 84.3 (82.0–86.5) |

|

| |||

| User over-the-counter Medications (N=1252) | 42.2 (39.6–44.7) | 40.6 (36.5–44.8)* | 43.2 (40.7–45.8) |

|

| |||

| Use Dietary Supplements (N=1424) | 49.4 (46.1–52.7) | 49.5 (44.9–54.0)* | 49.4 (45.6–53.2) |

|

| |||

| Use Any Medication (N=2699) | 90.6 (89.1–92.0) | 88.7 (86.3–91.2)* | 91.8 (90.3–93.4) |

|

| |||

| Use 1 or more Alcohol- Interacting Medication (N=1726) | 57.7 (55.1–60.3) | 51.0 (47.4–54.6)* | 62.3 (59.4–65.2) |

|

| |||

| Drinking Frequency (Number of drinks per day) | |||

|

| |||

| 1 drink per day (N=474) | 16.9 (9.2–24.8) | 42.2 (37.9–46.4) | 0 |

|

| |||

| 2 or 3 drinks per day (N=498) | 19.7 (12.0–31.3) | 46.7 (42.0–51.3) | 0 |

|

| |||

| ≥4 drinks per day (N=134) | 4.6 (2.2–7.2) | 11.2 (9.2–13.2) | 0 |

Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) for chi-square test between regular drinkers and non-regular drinkers.

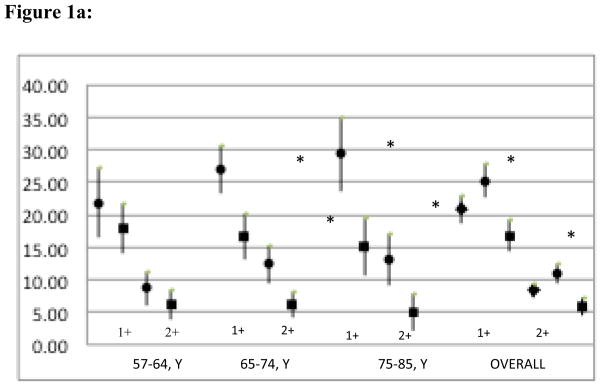

Among the 165 alcohol-interacting medications identified in Micromedex, respondents in our sample used 76 medications. While 57.7% of older adults in the U.S. use at least 1 alcohol-interacting medication, approximately 21% (95% CI 18.7, 23.0) of older adults are at-risk for a drug-alcohol interaction (regular drinkers that concurrently use at least one alcohol-interacting medication). The prevalence of potential drug-alcohol interactions increased with age for men, but not women, and was highest among men in the oldest age group (75–84). The prevalence of any drug-alcohol interaction was highest in men as compared to women across all age groups.

Figure 1 also depicts the prevalence of multiple (2 or more) drug-alcohol interactions by age and gender. Approximately 8.3% of respondents reported the concurrent use of 2 or more alcohol-interacting medications with regular drinking; men were significantly (P<0.05) more likely than women to be at-risk for multiple drug-alcohol interactions. The difference between men and women persists across the older age groups, but not the 57–64 years age group.

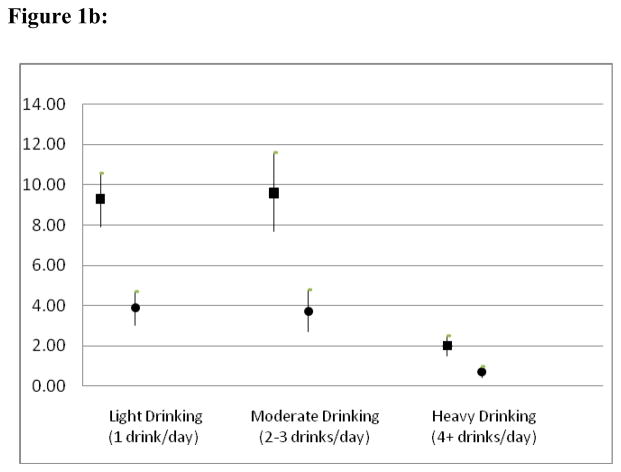

Figure 1.

Figure 1a: Weighted Prevalence Estimates (%) of Potential Drug-Alcohol Interactions Among Older Adults by Number of Interactions Overall and by Age and Gender in the US.

Shape: circle denotes Men; square Women; diamond Overall; Error Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. * Statistically significant difference (P-value <0.05) between men and women using the chi-square test.

Figure 1b: Weighted Prevalence (%) Estimates of Drug-Alcohol Interactions by Drinking Frequency Among Older Adults in the U.S.

Shape: square denotes 1 ore more drug-alcohol interaction and circle denotes 2 or more drug alcohol interactions Error Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2 depicts the likelihood of a potential drug-alcohol interaction stratified by respondents’ socio-demographic and health characteristics. Potential drug-alcohol interactions were significantly (p<0.05) more likely in men, White, non-Hispanic older adults, wealthier respondents and among those with a greater formal education than their counterparts. Further, individuals with increasing co-morbidity are also significantly more likely to experience a potential drug-alcohol interaction.

Table 2.

Characteristics Associated With Drug-Alcohol Interactions Among Older Adults in the U.S. (N=2975)

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Prevalence | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted ORa |

| Age, y | |||

| 57–64 | 39.6 (33.7–45.5) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||

| 65–74 | 36.2 (31.5–40.9) | 1.11 (0.85–1.46) | 1.13 (0.86–1.48) |

|

| |||

| 75–85 | 24.2 (19.5–28.9) | 1.09 (0.82–1.47) | 1.14 (0.85–1.52) |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 58.8 (55.3–62.3) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||

| Women | 41.2 (37.7–44.7) | 0.60 (0.51–0.69)* | 0.59 (0.51–0.69)* |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 87.3 (83.5–91.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 6.8 (4.2–9.5) | 0.58 (0.39–0.85)* | 0.59 (0.41–0.85)* |

|

| |||

| Hispanic, any race | 4.6 (2.6–6.6) | 0.56 (0.33–0.96)* | 0.56 (0.33–0.96)* |

|

| |||

| Other | 1.2 (0.2–2.2) | 0.38 (0.15–1.00) | 0.36 (0.14–0.95)* |

|

| |||

| Income, $ | |||

| <25,000 | 14.2 (10.1–18.4) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||

| 25,000–50,000 | 41.6 (35.7–47.4) | 3.07 (2.22–4.23)* | 3.11 (2.25–4.32)* |

|

| |||

| >50,000–74,999 | 12.5 (9.0–15.9) | 2.29 (1.44–3.64)* | 2.42 (1.53–3.83)* |

|

| |||

| ≥75,000 | 31.7 (24.7–38.7) | 3.62 (2.40–5.45)* | 3.91 (2.56–5.99)* |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| <HS | 10.1 (7.1–13.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||

| HS graduate/GED | 21.5 (17.8–25.1) | 1.54 (1.09–2.18)* | 1.58 (1.12–2.22)* |

|

| |||

| Some college/AA/Voc. | 34.7 (30.5–39.0) | 2.45 (1.81–3.32)* | 2.58 (1.90–3.50)* |

|

| |||

| Bachelors/above | 33.7 (28.0–39.3) | 3.08 (2.19–4.34)* | 3.04 (2.20–4.20)* |

|

| |||

| Self-Reported Health | |||

| Poor | 5.9 (3.3–8.5) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||

| Fair | 18.0 (14.4–21.7) | 1.19 (0.76–1.85) | 1.19 (0.77–1.84) |

|

| |||

| Good | 31.5 (27.0–36.1) | 1.29 (0.81–2.05) | 1.33 (0.83–2.13) |

|

| |||

| Very Good | 33.1 (27.9–38.2) | 1.20 (0.78–1.86) | 1.22 (0.79–1.86) |

|

| |||

| Excellent | 11.5 (8.4–14.6) | 1.01 (0.57–1.73) | 1.03 (0.60–1.76) |

|

| |||

| Insurance Coverage | |||

| None | 3.8 (2.1–5.5) | 0.68 (0.42–1.11) | 0.66 (0.41–1.06) |

|

| |||

| Medicare | 60.4 (54.0–66.8) | 1.15 (0.89–1.48) | 1.24 (0.97–1.59) |

|

| |||

| Medicaid | 4.0 (2.3–5.7) | 0.61 (0.39–0.96)* | 0.61 (0.40–0.94)* |

|

| |||

| Private Insurance | 71.2 (65.8–76.6) | 1.71 (1.33–2.21)* | 1.73 (1.36–2.21)* |

|

| |||

| VA | 7.7 (5.0–10.3) | 1.15 (0.82–1.62) | 0.94 (0.67–1.31) |

|

| |||

| Other | 10.6 (6.9–14.2) | 0.82 (0.53–1.26) | 0.86 (0.56–1.31) |

|

| |||

| Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 | 19.3 (14.6–24.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

|

| |||

| 1–4 | 73.1 (68.1–78.1) | 1.46 (1.08–1.97)* | 1.52 (1.14–2.04)* |

|

| |||

| 5+ | 7.6 (5.2–9.9) | 1.63 (1.05–2.52)* | 1.62 (1.07–2.46)* |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio;

Notes: Adjusted Model includes all variables in the table (age group, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, education, self-reported health, insurance coverage, comorbidity index);

Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) using chi-square test.

Overall, drug-alcohol interactions were most common among older adults reporting a diagnosis of liver disease; 35% were regular drinkers concurrently using at least 1 alcohol-interacting medication. Aspirin and aspirin-containing analgesics were the most commonly used alcohol-interacting medication across all health conditions with the exception of metformin which was more common among older adults with diabetes. Across all age groups men with diabetes or hypertension were significantly (p<0.05) more likely to experience a drug-alcohol interaction in comparison to women. (Appendix S2)

As presented in Table 3, overall, 4%, 19%, and 3% of older adult individuals are potentially at-risk for a drug-alcohol interaction of major, moderate and/or minor severity, respectively, and, less than 1% of individuals were using contraindicated alcohol interacting medications concurrently with regular drinking. More than half of potential-drug alcohol interactions involved the use of alcohol interacting analgesics; 3.4% and 11% of older adults are regularly using analgesics such as aspirin, acetaminophen and/or narcotics concurrently with alcohol. Further, 7% of older adults are regular drinkers and concurrently using alcohol-interacting psychotropic medications, such as antidepressants, anxiolytics and sedatives.

Table 3.

Weighted Prevalence Estimates of Drug-Alcohol Interactions by Interaction Severity and Therapeutic Class of Alcohol-Interacting Medication Overall and by Gender and Age Group (N=2975)

| Therapeutic Class (No. of users) | 57–64,y (N=1015)

|

65–74,y (N=1082)

|

75–85,y (N=878)

|

Total (N=2975) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (N=525) | Women (N=490) | Men (N=543) | Women (N=539) | Men (N=377) | Women (N=501) | ||

| Major Severity | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall (N=126) | 5.0 (3.1–6.9) | 4.2 (2.2–6.2) | 6.0 (4.1–7.9)* | 2.3 (1.0–3.7) | 5.1 (2.4–7.8) | 2.9 (1.0–4.9) | 4.3 (3.5–5.1) |

|

| |||||||

| Antidiabetics (N=98) | 7.3 (4.7–9.8) | 1.1 (0.0–2.2) | 5.6 (3.7–7.5)* | 1.4 (0.4–2.4) | 2.6 (0.9–4.2) | 1.4 (0.2–2.6) | 3.4 (2.5–4.3) |

|

| |||||||

| Analgesics (N=78) | 2.1 (0.9–3.2)* | 3.5 (1.6–5.4) | 3.3 (1.7–5.0) | 1.3 (0.4–2.2) | 3.8 (1.3–6.3) | 2.5 (0.7–4.3) | 2.7 (2.0–3.4) |

|

| |||||||

| Narcotic Analgesics | 1.0 (0.0–1.9) | 1.3 (0.0–3.0) | 1.6 (0.4–2.8) | 0.6 (0.1–1.1) | 1.0 (0.0–1.9) | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) | 1.0 (0.5–1.5) |

|

| |||||||

| Hydrocodone | 0.7 (0.0–1.5) | 0.6 (0.0–1.5) | 1.4 (0.3–2.6) | 0.6 (0.1–1.1) | 0.7 (0.0–1.6) | 0.3 (0.0–0.8) | 0.7 (0.3–1.1) |

|

| |||||||

| Oxycodone | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) | 0.8 (0.0–2.1) | 0.2 (0.0–0.6) | 0 (0) | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (0.0–0.6) |

|

| |||||||

| Other Analgesics | 1.0 (0.1–1.8) | 2.0 (0.6–3.5) | 1.5 (0.3–2.7) | 0.7 (0.0–1.5) | 2.2 (0.0–4.4) | 2.4 (0.6–4.1) | 1.6 (0.9–2.2) |

|

| |||||||

| Acetaminophen | 1.7 (0.6–2.7) | 2.8 (1.0–4.5) | 3.1 (1.5–4.7) | 1.0 (0.2–1.9) | 2.4 (0.7–4.1) | 2.1 (0.5–3.7) | 2.1 (1.5–2.8) |

|

| |||||||

| Tramadol | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | 0.9 (0.0–1.8) | 0.4 (0.0–1.0) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (0.0–3.3) | 0.4 (0.0–1.0) | 0.5 (0.1–0.8) |

|

| |||||||

| Moderate Severity | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall (N=503) | 20.2 (14.9–25.6)* | 14.6 (10.8–18.4) | 25.1 (21.3–28.8)* | 14.2 (10.4–18.0) | 26.3 (20.5–32.1)* | 12.9 (8.6–17.2) | 18.5 (16.3–20.7) |

|

| |||||||

| Analgesics(N=300) | 12.1 (8.3–16.0) | 6.3 (3.6–9.0) | 16.1 (12.7–19.5) | 8.7 (5.8–11.5) | 17.5 (11.3–23.7) | 8.0 (4.6–11.4) | 11.0 (9.4–12.7) |

|

| |||||||

| Narcotic Analgesics (N=3) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | 0.2 (0.0–0.6) | 0.3 (0.0–0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) |

|

| |||||||

| Aspirin (N=296) | 12.1 (8.3–16.0) | 6.2 (3.5–8.8) | 15.9 (12.5–19.3) | 8.4 (5.6–11.2) | 17.5 (11.3–23.7) | 8.0 (4.6–11.4) | 10.9 (9.2–12.6) |

|

| |||||||

| Psychotropic Medications (N=204) | 4.9 (2.6–7.2)* | 9.9 (7.0–12.9) | 9.3 (6.3–12.4) | 8.1 (5.3–10.8) | 7.7 (4.8–10.7) | 6.4 (4.0–8.8) | 7.7 (6.6–8.8) |

|

| |||||||

| Antidepressants (N=90) | 2.2 (0.8–3.6) | 5.8 (3.7–7.9) | 3.8 (1.8–5.9) | 3.4 (1.5–5.3) | 1.6 (0.0–3.2) | 3.2 (1.2–5.2) | 3.5 (2.7–4.3) |

|

| |||||||

| Anxiolytics, Sedatives, & Hypnotics (N=68) | 2.3 (0.6–4.0) | 2.5 (1.1–3.9) | 3.0 (1.1–4.8) | 2.6 (0.8–4.4) | 2.3 (0.9–3.6) | 2.0 (0.8–3.2) | 2.5 (1.7–3.2) |

|

| |||||||

| Vitamins (N=65) | 2.2 (0.6–3.8) | 2.7 (0.7–4.7) | 3.4 (2.0–4.8) | 2.3 (0.8–3.7) | 4.0 (1.4–6.6) | 0.4 (0.0–1.0) | 2.5 (1.7–3.2) |

|

| |||||||

| Warfarin (N=45) | 0.8 (0.0–1.7) | 0.9 (0.0–1.9) | 2.1 (1.0–3.2) | 0.4 (0.0–0.9) | 7.0 (4.0–9.9) | 0.9 (0.0–1.8) | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) |

|

| |||||||

| Others (N=35) | 1.6 (0.6–2.6) | 1.0 (0.0–2.1) | 1.0 (0.0–1.9) | 0.7 (0.0–1.4) | 2.8 (0.2–5.4) | 0.5 (0.0–1.1) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) |

|

| |||||||

| Minor Severity | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall (N=81) | 1.5 (0.2–2.7)* | 4.3 (1.6–7.0) | 4.8 (2.4–6.0) | 3.0 (1.3–4.6) | 4.9 (1.8–8.1)* | 1.5 (0.7–2.3) | 3.1 (2.4–3.9) |

|

| |||||||

| Folic Acid (N=52) | 1.2 (0.0–2.4) | 2.4 (0.5–4.2) | 2.8 (1.5–4.0) | 2.1 (0.7–3.4) | 3.7 (1.1–6.3) | 0.4 (0.0–1.0) | 2.0 (1.3–2.7) |

|

| |||||||

| Beta Blockers (N=6) | 0 (0) | 0.6 (0.0–1.9) | 0.8 (0.0–1.9) | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) |

|

| |||||||

| Contraindicated Severity | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall (N=3) | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.5 (0.0–1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) |

Several therapeutic classes may belong in multiple severity categories. Antidiabetics include: Glipizide, Glipizide–Metformin, Glyburide, Glyburide-Metformin, Insulin, Metformin, and Tolazamide. Other medications include: Nitroglycerin, Methotrexate, Metoclopramide, Prochlorperazine, Tadalafil, Yohimbine, Tizanidine, and Valerian. Overall- Contraindicated include Metronidazole and Topiramate.

Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between men and women using chi-square test.

There were significant gender differences in the types of alcohol-interacting medication use among older adults. Prevalence of a major drug-alcohol interaction with anti-diabetic agents and analgesics was significantly greater in men aged 57–64 in comparison to their female counterparts. While potential drug-alcohol interactions with psychotropic medications were more common among women aged 57–64 years in comparison to men in the same age group, the use of anxiolytics and sedatives was equally common in men and women across all age groups. With the exception of men aged 65–75, antidepressants were used more frequently in combination with regular alcohol consumption in women.

As expected, the types of medications most commonly combined with regular drinking varied between age groups for men and women. For example, men in the oldest age group (75–84) were significantly more likely to drink regularly and concurrently use analgesics and psychotropic medications, in comparison to their 57–64 counterparts who were more likely to use anti-diabetic agents in combination with alcohol. Further, younger women 57–64 were more likely to use psychotropic medications, while women in the oldest age group were more likely to use aspirin in combination with alcohol.

Table 4 presents the weighted prevalence of drug-alcohol interactions by drinking status and frequency. In comparison to non-regular drinkers, regular drinkers were significantly (p-value <0,05) less likely to use alcohol-interacting narcotic analgesics (2.4% vs. 4.1%), acetaminophen (5.3% vs. 9.7%), and diabetes medications (8.4% vs. 18.0%) and psychotropic medications (18.9% vs. 25.4%). We also found that heavy drinkers (4 or more drinks per day) were significantly less likely to use alcohol interacting psychotropic medications (13.0%) in comparison to light (18.9%) and moderate (20.3%) drinkers. These findings persist in multivariate analyses controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity and education.

Table 4.

Weighted Prevalence Estimates of Alcohol-Interacting Medication Use by Therapeutic Class and Drinking Frequency Among Older Adults (N=2975)

| Overall | Non-Regular Drinkers (N=1869) |

Regular Drinkers (N=1106) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Class of Alcohol-Interacting Medication |

≤1 drink per day (N=474) |

2 to 3 drinks per day (N=498) |

≥4 drinks per day (N=134) |

Overall (Any Frequency) |

Interaction Effect/Outcome |

||

| Antidiabetics | 14.0 (12.4–15.6) | 18.0(15.8–20.1)* | 8.0 (5.6–10.3)** | 8.7 (5.2–12.3) | 8.4 (3.1–13.7) | 8.4 (6.2–10.5) | Prolonged hypoglycemia, disulfiram-like reactions; Lactic Acidosis with metformin. |

| Analgesics | 9.9 (8.4–11.4) | 12.2 (10.3–14.2)* | 6.7 (4.4–9.0)** | 6.4 (4.3–8.5) | 6.7 (2.4–11.0) | 6.6 (4.8–8.3) | - |

| Narcotic Analgesics | 3.4 (2.4–4.4) | 4.1 (2.7–5.5)* | 1.9 (0.2–3.5)** | 2.8 (1.1–4.5) | 2.9 (0.0–6.6) | 2.4 (1.2–3.7) | Increased risk of fatal overdose |

| Acetaminophen | 7.9 (6.4–9.4) | 9.7 (7.9–11.5)* | 4.9 (2.8–7.1)** | 5.4 (3.2–7.5) | 6.1 (1.9–10.3) | 5.3 (3.7–6.8) | Increased risk of hepatoxicity |

| Aspirin | 28.0 (25.3–30.7) | 28.9 (25.8–31.9)* | 27.8 (23.8–31.9)** | 26.6 (21.2–32.0) | 22.4 (15.5–29.2) | 26.7 (23.2–30.1) | Increased gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Psychotropic Medications | 22.8 (21.1–24.4) | 25.4 (23.1–27.8)* | 18.9 (15.3–22.6)** | 20.3 (15.2–25.4) | 13.0 (7.9–18.1) | 18.9 (16.4–21.4) | Increased sedation |

| Antidepressants | 10.8 (9.3–12.3) | 12.4 (10.1–14.6)* | 9.6 (6.6–12.5)** | 8.1 (4.8–11.4) | 6.4 (3.5–9.3) | 8.5 (6.5–10.6) | Enhanced CNS depression & cognitive impairment |

| Anxiolytics, Sedatives, & Hypnotics | 8.2 (7.2–9.1) | 9.7 (8.3–11.0)* | 7.1 (4.9–9.3)** | 5.4 (2.6–8.2) | 4.5 (0.8–8.1) | 6.0 (4.3–7.7) | Increased sedation |

| Vitamins | 5.6 (4.7–6.5) | 5.4 (4.5–6.3) | 6.6 (4.2–8.9)** | 5.9 (3.1–8.7) | 4.4 (0.9–7.8) | 6.0 (4.1–7.9) | Increase side effects of flushing and pruritus |

| Warfarin | 4.4 (3.7–5.1) | 4.7 (3.6–5.8)* | 4.7 (2.9–6.6)** | 3.7 (2.1–5.4) | 1.8 (0.0–4.5) | 3.9 (2.8–5.0) | Increase risk of bleeding |

| Folic Acid | 4.2 (3.3–5.2) | 3.8 (2.8–4.8) | 5.6 (3.7–7.6)** | 4.4 (2.0–6.8) | 4.4 (0.9–7.8) | 4.9 (3.3–6.6) | Decrease folic acid serum levels |

Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) using chi-square test between regular and non-regular drinkers.

Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) using chi-square test between drinking frequency (≤1, 2–3, or ≥4 drinks/day) amongst regular drinkers.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is the first study to use a nationally representative, population-based sample of older adults in the United States to examine the concurrent use of medications and alcohol. Our analyses indicate that one in five older adults in the U.S. are potentially at-risk for a drug-alcohol interaction, particularly older men between the ages of 75–85, and more than half of these interactions involved non-prescription medications, specifically aspirin. Further, nearly 1 in 10 older adults are using multiple alcohol-interacting medications and are regularly drinking alcohol. Thus, efforts to avoid the potential for drug-alcohol interactions among older adults is warranted, especially considering evidence that older adults that drink alcohol regularly are more likely to be admitted for an adverse drug event,4 and more than 25% of emergency room admissions are associated with a drug-alcohol interactions.7

Our estimates of drug-alcohol interactions are greater than those reported among adults 20 years and older in the 1999–2002 NHANES study9, the only national population-based study of drug-alcohol interactions in the U.S. This is not surprising considering this prior study excludes non-prescription medications, and the use of both prescription and non-prescription medications, including alcohol-interacting medications, increases with age.1 Further, the higher prevalence of drug-alcohol interactions may also be related to the increasing prevalence of unhealthy drinking in older adults in the U.S.2 While our findings are similar to those reported by Pringle et al 8 differences in data source and definitions of alcohol-interacting medications limit comparability.

Our findings suggest that efforts to improve the safe use of medications in older adults should focus on increasing patient awareness of the health risks associated with the use of specific medications concurrently with alcohol, particularly among individuals that are regular, heavy (or binge) drinkers. While drinking is quite common among older adults, increasing patient awareness to facilitate more informed decisions about drinking behavior and medication use is especially important considering the increasingly unhealthy drinking patterns identified in the older adult U.S. population. 14

The use of alcohol-interacting non-prescription medications are particularly noteworthy. More than half of the drug-alcohol interactions we identified involved an over-the-counter medication or dietary supplement; For example, 11%, 3% and 2% of older adults in the U.S. are regularly using aspirin, vitamins and acetaminophen, respectively, concurrently with alcohol. These medications are available without a prescription and physicians often do not ask patients about their use of over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements.15 Therefore, patients may not be aware of the potential harmful interaction effects with alcohol.

Our findings indicate that the risk for drug-alcohol interactions increases with age, particularly for men, and is highest among men 75–85. We also found that older adults with multiple chronic conditions, particularly those with liver disease, hypertension, diabetes and depression, have the highest prevalence of drug-alcohol interactions. In order to avoid potentially harmful drug-alcohol interactions in these at-risk chronically ill subpopulations, providers should regularly ask their patients about their drinking behavior and medication use.

We also found several medications commonly used in the older adult population to be major contributors of drug-alcohol interactions; for example, analgesics such as acetaminophen and hydrocodone, antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine) for sleep and/or allergies, aspirin for cardiovascular prevention, glyburide and metformin for diabetes and benzodiazepines as sedatives; Providers may consider substituting alcohol-interacting medications among at-risk patients to non-alcohol interacting medications with similar therapeutic indications. While this may be possible for some medications (e.g. antihistamines), it may not be feasible for others (e.g. metformin). Providers may also consider reducing prescriptions for alcohol-interacting medications among patients most at-risk such as those with liver and kidney disease.

While our findings have focused on the prevalence and patterns of drug-alcohol interactions among the older adult population in the U.S., we also found that the use of alcohol-interacting medications, particularly analgesics, diabetes and psychotropic medications was significantly lower among regular drinkers in comparison to their counterparts. We also found that among regular drinkers, those that report heavy or binge drinking are less likely to use a series of alcohol-interacting medications, compared to their counterparts. These findings suggest physicians may be asking their patients about their drinking behavior, and tailoring their prescribing practices accordingly. This is reassuring considering prior evidence that physicians often do not counsel patients on medication interactions with alcohol.5,16

LIMITATIONS

Our study has several limitations. We examine the potential for drug-alcohol interactions and not actual interactions. Also, there is a broad range of factors that influence adverse drug effects of alcohol consumption (e.g. liver function, dose, type of interaction, timing of dose). We use the Micromedex drug-interaction software to identify potential interactions in our sample. There are multiple data sources used in clinical settings to identify drug interactions with varying definitions. For example, several data sources include statins and ibuprofen as alcohol-interacting medications, while Micromedex does not. In addition, Micromedex identifies some medications as alcohol-interacting, while other software (e.g. Lexi-comp) does not. Therefore, our findings may over or underestimate the prevalence of specific types of drug-alcohol interactions. Our findings may also overestimate the potential for harm from drug-alcohol interactions because we have derived this estimate based on regular-drinkers (at least 1 drink per week), and the timing of medication use is not incorporated. However, to better estimate the magnitude of this problem, we also provide estimates of drug-alcohol interactions based on drinking frequency.

CONCLUSION

Our findings suggest that the concurrent use of medications with alcohol among older adults in the U.S. is an important, yet under-recognized, public health problem. The potential for drug-alcohol interactions among the older adult population in the U.S. is significant with important clinical implications, particularly for the oldest old and the chronically ill. Strategies to better monitor and prevent the use of alcohol-interacting medications among regular drinkers are warranted in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) is supported by the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Aging, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Office of AIDS Research, and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (5R01AG021487). NSHAP is also supported by NORC, whose staff was responsible for the data collection. Supplies were donated to the NSHAP study by OraSure, Sunbeam, A & D Medical/LifeSource, Wilmer Eye Institute at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Schleicher & Schuell Bioscience, BioMerieux, Roche Diagnostics, Digene, and Richard Williams.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Dima M. Qato and Todd Lee study concept and design, Dima M. Qato acquisition of subjects and/or data, Dima M. Qato, Todd Lee, and Beenish S. Manzoor were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data, and Dima M. Qato, Todd Lee and Beenish S. Manzoor were involved in the preparation of manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper.

References

- 1.Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, et al. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:2867–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merrick EL, Horgan CM, Hodgkin D, et al. Unhealthy drinking patterns in older adults: prevalence and associated characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003;289:1107–1116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes AJ, Moore AA, Xu H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of at-risk drinking among older adults: The project SHARE study. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:840–846. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saitz R, Horton NJ, Samet JH. Alcohol and medication interactions in primary care patients: Common and unrecognized. Am J Med. 2003;114:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weathermon R, Crabb DW. Alcohol and medication interactions. Alcoh Res Health. 1999;23:40–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.HDH . Effects of alcohol, alone and incombination with medications: Prevention Research Center. Walnut, Creek California: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pringle KE, Ahern FM, Heller DA, et al. Potential for alcohol and prescription drug interactions in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1930–1936. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jalbert JJ, Quilliam BJ, Lapane KL. A profile of concurrent alcohol and alcohol-interactive prescription drug use in the US population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1318–1323. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0639-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qato DM, Schumm LP, Johnson M, et al. Medication data collection and coding in a home-based survey of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64 (Suppl 1):i86–93. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morenoff JD, House JS, Hansen BB, et al. Understanding social disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control: The role of neighborhood context. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1853–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, et al. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging (NACDA) The National, Social Life, Health and Aging (NSHAP) Dataset. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/NACDA/news.html-nshap/

- 14.Merrick EL, Hodgkin D, Garnick DW, et al. Unhealthy drinking patterns and receipt of preventive medical services by older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1741–1748. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0753-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hensrud DD, Engle DD, Scheitel SM. Underreporting the use of dietary supplements and nonprescription medications among patients undergoing a periodic health examination. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:443–447. doi: 10.4065/74.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown RL, Dimond AR, Hulisz D, et al. Pharmacoepidemiology of potential alcohol-prescription drug interactions among primary care patients with alcohol-use disorders. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47:135–139. doi: 10.1331/XWH7-R0X8-1817-8N2L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.