Abstract

Background

Although research suggests that crisis hotlines are an effective means of mitigating suicide risk, lack of empirical evidence may limit the use of this method as a research safety protocol.

Purpose

This study describes the use of a crisis hotline to provide clinical backup for research assessments.

Methods

Data were analyzed from participants in the Emergency Department Safety and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) study (n=874). Socio-demographics, call completion data, and data available on suicide attempts occurring in relation to the crisis counseling call were analyzed. Pearson chi-squared statistic for differences in proportions were conducted to compare characteristics of patients receiving versus not receiving crisis counseling. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, there were 163 counseling calls (6% of total assessment calls) from 135 (16%) of the enrolled subjects who were transferred to the crisis line because of suicide risk identified during the research assessment. For those transferred to the crisis line, the median age was 40 years (interquartile range 27–48) with 67% female, 80% white, and 11% Hispanic.

Conclusions

Increasing demand for suicide interventions in diverse healthcare settings warrants consideration of crisis hotlines as a safety protocol mechanism. Our findings provide background on how a crisis hotline was implemented as a safety measure, as well as the type of patients who may utilize this safety protocol.

Keywords: Crisis Hotlines, Suicide Risk, Research Safety Protocol, Public Health

Introduction

Crisis hotlines are one of the oldest suicide prevention resources in the United States (Litman, Farberow, Shneidman, Heilig, & Kramer, 1965; Shneidman & Farberow, 1957). Research has shown that crisis hotlines are an effective way of mitigating active suicide risk (Gould, Kalafat, Harris-Munfakh, & Kleinman, 2007), yet there is no empirical evidence for using them for safety protocols during suicide research. Use of crisis hotlines may be a cost-effective and useful means of addressing the need for emergency response protocols during studies when trained mental health clinicians are not immediately available on-site.

We aim to discuss the utility, methodology, and implications of using a crisis hotline for clinician back-up during clinical research. This includes identifying characteristics of individuals being transferred to a crisis hotline during follow-up assessments as part of a suicide intervention study.

Method

The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) study (U01 MH088278; Boudreaux, Camargo, Miller) is a quasi-experimental clinical trial that included eight general medical emergency departments (EDs) across the United States (see Boudreaux et al., 2013 for full description). Eligible participants were ED patients aged 18 years or older with thoughts of killing themselves in the past week or an actual, aborted, or interrupted attempt in the past week. All participants completed a baseline assessment and were followed post-discharge (from ED or inpatient, if admitted). Following enrollment, each participant was telephoned by a trained interviewer at 6-, 12-, 24-, 36-, and 52-weeks for a follow-up assessment. In addition, chart reviews were conducted by a trained chart abstractor at the site at 6- and 12-months to assess suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Boudreaux et al., 2013).

ED-SAFE consists of three phases of data collection: (1) Treatment as Usual, (2) Universal Screening, and (3) Universal Screening + Intervention. The current study focuses on the first two phases, prior to the implementation of the multi-faceted suicide prevention intervention because no study-related interventions for suicidal patients were implemented in these phases, increasing the applicability of our study to general US EDs. Institutional review boards at all participating sites approved the study.

ED-SAFE contracted with Boys Town National Hotline (2015) through Link2Health Solutions, Inc., an administrator of crisis call networks, to ensure that a mental health counselor would always be on call during the telephone follow-up assessments, which were performed by trained, non-mental health research staff using a computer assisted telephone interview (CATI). Accredited by the American Association of Suicidology (AAS), Boys Town is open 24-hours/day, 365 days/year, and is staffed by specially trained counselors. For over 20 years, Boys Town has operated a professional, national hotline receiving over 8.5 million calls since its inception from across the United States. Spanish-speaking counselors and translation services are available. The hotline also has a comprehensive data system which allows staff to link callers with available services, including emergency aid in their immediate area or first responder services if needed. Boys Town established a dedicated ED-SAFE toll-free number and email address.

To ensure subject safety during ED-SAFE, calls were transferred to a crisis counselor in the following four situations: (1) Subject endorsed current active suicidal ideation; (2) Subject made a recent suicide attempt without seeking health care; (3) Interviewer encountered any other situation where he/she believed that the subject was at imminent risk of hurting him/herself or others; and (4) Interviewer encountered any other situation where the subject appeared to need additional resources, but the subject did not appear to be suicidal.

Thresholds for calling Boys Town were incorporated into the ED-SAFE programming of the CATI. This standardized the decision regarding mental health counseling and reduced complications introduced by relying on human judgment. The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS, Posner et al., 2011) was embedded in the follow-up survey to identify suicidal ideation severity and intensity, as well as attempt lethality.

Once connected with a crisis counselor (see Arias et al., 2014 for full description), a standardized evaluation was completed based on the three critical elements of the Boys Town crisis call model: (1) the problem (identify, ask, validate, assess, restate), (2) the options (evaluate, generate, explore), and (3) the plan (encourage follow through and future call backs, provide referrals, reconfirm self-harm contracts). If an actively suicidal participant hung up or was disconnected and the subject did not answer the crisis counselor’s call, the crisis counselor continued to try and reach the individual for up to 3 additional attempts over 60 minutes. If the crisis counselor was unable to reach the participant directly or through the emergency contact provided, the crisis counselor contacted the local police or emergency medical services (EMS).

Measures

Socio-demographics

A subset of demographic variables collected during the baseline assessment were examined including age, sex (male/female), race (non-white/white), and ethnicity (non-Hispanic/Hispanic).

Crisis counseling

Variables were created to document whether the subject had completed a crisis counseling call (yes/no), completed more than one call (yes/no), and when the call was completed (6-, 12-, 24-, 36-, or 52-weeks after enrollment).

Suicide attempts

Data collected at 6-, 12-, 24-, 36-, and 52-weeks after the initial ED visit were used to determine whether a suicide attempt was reported during the one-year period after the initial ED visit (yes/no).

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We performed descriptive statistics for the overall sample. Comparisons of charts among patients receiving versus not receiving crisis counseling were examined by using the Pearson chi-squared statistic for differences in proportions. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the first two phases of ED-SAFE there was a total of 874 subjects enrolled; the median age was 37 years (interquartile range = 27–47), 55% female, 74% white, and 13% Hispanic. There were 2,884 assessment calls completed, of which 163 (6%) were transferred to a crisis counselor. Of the 874 enrolled subjects, 135 (16%) were transferred to the crisis hotline and 131 (97%) completed a crisis counseling call. For those completing calls, the median age was 40 years (interquartile range 27–48) with 67% female, 80% white, and 11% Hispanic (Table 1). The only group difference between those receiving and not receiving crisis counseling was for sex where more females were transferred to a crisis counselor. Calls ranged from 1 to 61 minutes (median call length=14 minutes; interquartile range, 8–20). Most participants completed only one call and most calls were completed during the 52-week follow-up assessment (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients receiving versus not receiving crisis counseling during the non-intervention phases of ED-SAFE

|

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Received crisis counseling

|

Did NOT receive crisis counseling

|

P

|

||

| n | % | n | % | ||

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Overall | 135 | 739 | |||

| Age | 0.49 | ||||

| 18–24 | 25 | 19% | 160 | 22% | |

| 25–29 | 19 | 14% | 83 | 11% | |

| 30–39 | 26 | 19% | 188 | 25% | |

| 40–49 | 38 | 28% | 174 | 24% | |

| 50–59 | 23 | 17% | 100 | 14% | |

| 60–69 | 3 | 2% | 28 | 4% | |

| 70–79 | 0 | 0% | 4 | 1% | |

| 80+ | 1 | 1% | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 45 | 33% | 341 | 46% | 0.09 |

| Female | 90 | 67% | 398 | 54% | 0.03 |

| Race | |||||

| Not White | 27 | 20% | 198 | 27% | 0.44 |

| White | 108 | 80% | 541 | 73% | 0.13 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Not Hispanic | 120 | 89% | 641 | 87% | 0.55 |

| Hispanic | 15 | 11% | 98 | 13% | 0.83 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants transferred to a crisis counselor

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total subjects enrolled during non-intervention phases | 874 | |

| Total crisis counseling calls documented | 163 | 19% |

| Total subjects transferred to crisis counselor | 135 | 16% |

| Subjects completing one crisis counseling call | 103 | 76% |

| Subjects completing more than one crisis counseling call | 28 | 21% |

| Subjects who hung up prior to call completion | 4 | 3% |

| At baseline, subject reported: | ||

| suicidal ideation only | 87 | 64% |

| suicide attempt | 48 | 36% |

| Call duration in minutes, median (IQR) | 14 (8–20) | |

| Week in study that call was completed | ||

| 6-week assessment | 0 | 0% |

| 12-week assessment | 39 | 24% |

| 24-week assessment | 33 | 20% |

| 36-week assessment | 34 | 21% |

| 52-week assessment | 57 | 35% |

| Reason for transfer to a crisis counselor | ||

| Currently suicidal | 133 | 82% |

| Had a recent suicide attempt without seeking health care | 25 | 15% |

| Subject was at imminent risk of hurting self | 2 | 1% |

| Subject needed additional resources, but was NOT suicidal | 3 | 2% |

| Total subjects reporting at least one suicide attempt after crisis counseling call completed | 27 | 20% |

| Timing of suicide attempt after crisis counseling call was completed | ||

| >6 weeks - ≤12 weeks | 0 | 0% |

| >12 weeks - ≤24 weeks | 11 | 41% |

| >24 weeks - ≤36 weeks | 3 | 11% |

| >36 weeks - ≤52 weeks | 13 | 48% |

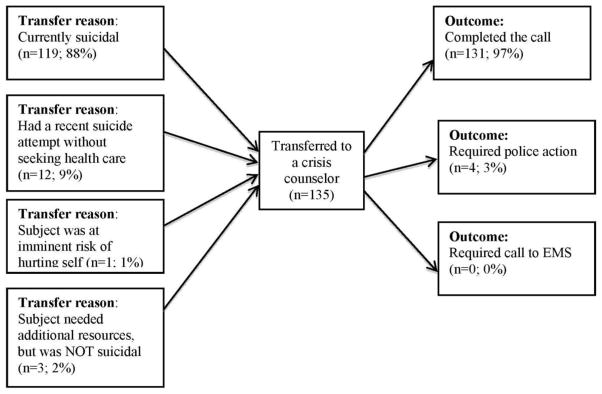

Of the 135 participants who were transferred to a crisis counselor during the study period, most (64%) reported suicidal ideation only (no current or past suicide attempts) during the baseline assessment. In addition, 27 (20%) reported at least one suicide attempt in the weeks following the crisis counseling call, yet all attempts were reported >12 weeks after the crisis counseling call (Table 2). Most individuals were transferred to a crisis counselor because they were currently suicidal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons for transfer to a crisis counselor and outcomes of the crisis call.

Discussion

Although crisis hotlines have been previously studied (e.g., Gilat & Shahar, 2007; Gould, Kalafat, Harris-Munfakh, & Kleinman, 2007; Witte et al., 2010), the current study is the first to investigate the use of crisis hotlines within the context of suicide research. With increasing demand for suicide interventions in diverse healthcare settings, consideration of crisis hotlines as a safety protocol mechanism is warranted. The current study provides data on patients transferred to a crisis counselor by study research staff during a suicide intervention study. Findings indicated that proportionately more females were transferred to a crisis counselor during the study, which is consistent with previous research on use of hotlines by suicidal individuals (Gould, Kalafat, Harris-Munfakh, & Kleinman, 2007). Most participants were transferred because they were currently suicidal and most completed only one counseling call. The high call completion rate (97%) suggests that this type of safety protocol can be successfully implemented with high-risk suicide populations.

Limitations

A limitation of the current study design is the lack of a control group (i.e., crisis counseling not offered as a safety protocol option). This design was chosen in response to ethical concerns about compromising the safety of participants in crisis. This limited the analysis on whether implementation of a crisis hotline as a safety protocol during the non-intervention phases of a study may affect study outcomes. Additional research is needed to determine whether the use of crisis hotlines has any impact on study outcomes. Second, the findings were limited to one crisis counseling program and cannot be generalized to all crisis counseling companies or models. However, the current findings do provide a framework upon which future research and design can be based.

Conclusions

Use of crisis hotlines may provide non-mental health researchers with the resources necessary to appropriately respond to patients with active suicide risk as part of the research protocol. Applications of these findings are particularly relevant to research looking for a cost-effective option for crisis counseling during the study timeframe. Our findings provide background on how a crisis hotline was implemented as a safety measure, as well as the type of patients who may utilize this safety protocol.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Office of Survey Research and the Boys Town teams for their dedication to the study and commitment to ensuring the safety of participants. In addition, we acknowledge the time and effort of the site principal investigators as well as the research coordinators and research assistants from the 8 participating sites.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The project described was supported by Award Number U01MH088278 from the National Institute on Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. None of the authors have financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah A. Arias, Butler Hospital and the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Ashley F. Sullivan, Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Ivan Miller, Butler Hospital and the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Carlos A. Camargo, Jr., Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Edwin D. Boudreaux, Departments of Emergency Medicine, Psychiatry, and Quantitative Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

References

- Arias SA, Zhang Z, Hillerns C, Sullivan AF, Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Camargo CA., Jr Using structured telephone follow-up assessments to improve suicide-related adverse event detection. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2014;44:537–547. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Goldstein AB, Sullivan AF, Allen MH, Manton AP, Arias SA, Camargo CA., Jr The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE): Methods and design considerations. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;36(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys Town National Hotline. Boys Town; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.boystown.org/national-hotline. [Google Scholar]

- Gilat I, Shahar G. Emotional first aid for a suicide crisis: Comparison between telephonic hotline and internet. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2007;70(1):12–18. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Kalafat J, Harris-Munfakh JL, Kleinman M. An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes part 2: Suicidal callers. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37(3):338–352. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman RE, Farberow NL, Shneidman ES, Heilig SM, Kramer JA. Suicide-prevention telephone service. JAMA. 1965;192(1):21–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.1965.03080140027006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner KP, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and interval consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescent and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shneidman ES, Farberow NL, editors. Clues to suicide. Vol. 56981. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Witte TK, Gould MS, Harris-Munfakh JL, Kleinman M, Joiner TE, Jr, Kalafat J. Assessing suicide risk among callers to crisis hotlines: A confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;66(9):941–964. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]