Abstract

Promotora Effectiveness Versus Metformin Trial (PREVENT-DM) is a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of a lifestyle intervention based on the Diabetes Prevention Program delivered by community health workers (or promotoras), metformin, and standard care. Eligibility criteria are Hispanic ethnicity, female sex, age ≥20 years, fluent Spanish-speaking status, BMI ≥23kg/m2, and prediabetes. We enrolled 92 participants and randomized them to one of the following three groups: standard care, DPP-based lifestyle intervention, or metformin. The primary outcome of the trial is the 12-month difference in weight between groups. Secondary outcomes include the following cardiometabolic markers: BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, and fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c), total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and insulin. PREVENT-DM participants are socioeconomically disadvantaged Latinas with a mean annual household income of $15,527 ± 9,922 and educational attainment of 9.7 ± 3.6 years. Eighty-six percent of participants are foreign born, 20% have a prior history of gestational diabetes, and 71% have a first-degree relative with diagnosed diabetes. At baseline, PREVENT-DM participants had a mean age of 45.1 ± 12.5 years, weight of 178.8 ± 39.3lbs, BMI of 33.3 ± 6.5kg/m2, HbA1c of 5.9 ± 0.2%, and waist circumference of 97.4 ± 11.1cm. Mean baseline levels of other cardiometabolic markers were normal. The PREVENT-DM study successfully recruited and randomized an understudied population of Latinas with prediabetes. This trial will be the first U.S. study to test the comparative effectiveness of metformin and lifestyle intervention versus standard care among prediabetic adults in a “real-world” setting.

1. INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes affects 28.9 million adults in the United States; and 86 million Americans are estimated to have prediabetes, a high-risk state for developing diabetes.1 Previous research has reported that 25 to 50% of individuals with prediabetes will develop type 2 diabetes within 5 years.2 The prevalence of diabetes is higher among U.S. Latinos (20.1%) than whites (11.0%),3 and the lifetime risk of developing diabetes is highest among Latinos,4 suggesting that diabetes disparities may worsen as this population continues to grow.5 Among Latinos, Hispanic women (hereafter called Latinas) have a higher lifetime diabetes risk (52%) than males (45%).4 These data underscore the importance of developing effective interventions to prevent diabetes among all Latinos, and especially Latinas.

The U.S. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) clinical trial demonstrated that intensive lifestyle intervention and metformin are both effective treatments to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes in adults with prediabetes.6 Similar to other efficacious lifestyle interventions,7,8 the DPP lifestyle intervention consisted of a structured diet and physical activity program with 2 principal goals: 1) performing at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity; and 2) achieving at least 7% weight loss from baseline. DPP participants were randomized to receive either the intensive lifestyle intervention, metformin 850mg or placebo twice daily. Relative to placebo, the reduction in diabetes incidence was 58% for the lifestyle intervention and 31% for metformin.6

A large body of translational research has adapted and tested the DPP lifestyle intervention in “real-world” settings, demonstrating that this program is effective when delivered by interventionists with various training backgrounds in diverse target populations.9 Despite the reported efficacy of metformin in the original DPP trial, there has been much less focus on disseminating and studying the effectiveness of this diabetes prevention treatment in pragmatic settings. Only one published study, which was conducted in India, included a metformin arm compared to a DPP-based lifestyle intervention, the two treatments combined, or placebo.10 Therefore, the existing literature provides little evidence to guide the choice of diabetes prevention treatments by at-risk individuals and their healthcare providers in the U.S.

The trial protocol described here aims to determine, in a “real-world” setting, the comparative effectiveness of metformin and a DPP-based lifestyle intervention, compared to standard care among Latinas with prediabetes. Based on our pilot data and findings from DPP,11,6 we hypothesize that both the lifestyle intervention and metformin will result in significant weight loss relative to standard care. We chose Latinas as the target population because: 1) they have the highest risk of developing diabetes relative to Hispanic men and other demographic groups;, 2) their culturally-shaped influence on family members’ lifestyle behaviors may result in a multiplying effect of the study interventions;12–14 and 3) previous DPP translation studies across all racial/ethnic groups have included mostly women, while citing challenges to engaging men.9 This paper presents the rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of this novel comparative effectiveness study, called the Promotora Effectiveness Versus Metformin Trial (PREVENT-DM).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design and participants

PREVENT-DM is a three-arm randomized controlled trial with a parallel group design, comparing standard care to metformin or a group-based adaptation of the DPP lifestyle intervention delivered by community health workers. This protocol has been approved by the Temple University and Northwestern University Institutional Review Boards, and is recorded in the National Clinical Trials Registry (NCT02088034).

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for PREVENT-DM are listed in Table 1. Participants are women of self-reported Latina ethnicity, who are fluent Spanish speakers and at least 20 years old. In addition, participants must have a BMI ≥ 23kg/m2 and prediabetes defined according to the most recent American Diabetes Association criteria: fasting plasma glucose concentration of 100–125mg/dL and/or hemoglobin A1C from 5.7–6.4%.15 This BMI cutoff was selected because of the high prevalence of prediabetes among normal-weight Latinas.16 Potential participants were excluded if they met any of following criteria: current or planned pregnancy during the study period; diabetes at baseline; current participation in a supervised weight loss program; chronic conditions that could affect their ability to participate; medical comorbidities that could influence body weight; medications that could affect weight or glucose metabolism; or contraindication to metformin.

Table 1.

PREVENT-DM Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria |

| Sociodemographic |

| Women |

| Latino ethnicity |

| Fluent Spanish speaker |

| Age ≥20 years |

| Anthropomorphic and glycemic measuresa |

| Body mass index ≥23kg/m2 |

| Fasting plasma glucose 100–125mg/dL |

| Hemoglobin A1C 5.7–6.4% |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Current participation in a supervised weight loss program |

| Diabetes |

| Current or planned pregnancy |

| Medical conditions that could affect participation |

| Cardiovascular event or angina in prior 6 months |

| Uncontrolled hypertension (≥160/100mmHg) |

| Pulmonary disease with oxygen requirement |

| Orthopedic conditions limiting regular activities |

| Severe psychiatric illnessb |

| Medical conditions that could affect outcomes |

| HIV |

| Cancer requiring treatment in past 5 yearsc |

| Uncontrolled thyroid diseased |

| Medications affecting outcomese |

| Contraindications to metformin |

| Hypersensitivity to metformin |

| Serum creatinine ≥1.4mg/dL |

Participants were eligible based on meeting the BMI criterion and at least one of the glycemic criteria listed.

Psychiatric illnesses excluded were depression with suicidal ideation, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or substance abuse.

Participants were not excluded based on a history of non-melanoma skin cancer.

Uncontrolled thyroid disease was defined as the presence of hypothyroidism with a thyroid stimulating hormone level outside the therapeutic range within the last 6 months.

Medications that could impact weight or glucose metabolism were considered exclusions (e.g. systemic corticosteroids, topiramate, and bupropion).

2.2 Rationale and description of the metformin intervention

Metformin is a biguanide agent that has been extensively studied as a treatment for type 2 diabetes in seminal clinical trials demonstrating its long-term safety and effectiveness for this indication.17,18 More recent trials have tested the efficacy of metformin as a treatment to prevent or delay the onset of diabetes among high-risk individuals. The multi-site U.S. Diabetes Prevention Program clinical trial was one of the largest such studies with a total of 3,234 participants with prediabetes, 10.5% of whom were Latinas. The DPP demonstrated a 31% reduction in diabetes incidence with metformin treatment relative to placebo.6 This relative risk reduction remained at 25% after participants stopped taking metformin for 1–2 weeks.19 Other clinical trials studying metformin in those at high risk for diabetes have reported comparable relative risk reductions.20

Metformin has also been found to induce modest weight loss among individuals with prediabetes, which is considered the primary mechanism explaining its efficacy in preventing or delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes.21 In the DPP, participants randomized to the metformin arm lost 5.6 lbs at 12 months, corresponding to 2.7% of their initial body weight.22 The only DPP translational trial to study metformin found no weight loss among those receiving this medication, lifestyle intervention, or both treatments combined.10 However, the dosage of metformin administered in this trial was lower than in DPP, and this study enrolled South Asian participants with a lower mean BMI (25.8) than DPP participants (34.0).6 Clinical trials examining metformin treatment among women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, overweight/obesity, and insulin resistance have demonstrated statistically significant reductions in weight compared to placebo.23,24 A meta-analysis including all randomized controlled trials of metformin in those at-risk for diabetes reported a statistically significant pooled weight loss relative to placebo or no treatment.20

In the current study, we chose to use metformin 850mg twice daily because this dose has been most widely used in the diabetes prevention literature,20 thereby facilitating comparisons with earlier efficacy trials including the DPP. Participants receiving metformin in the current trial start at a dose of 850mg daily for one month and take 850mg twice daily thereafter. For patients who experience gastrointestinal side effects, the metformin dose is reduced by half for one month before resuming the previous dose. If side effects recur, metformin is stopped for one month and then titrated to the highest dose tolerated up to a maximum of 850mg twice daily. During monthly study visits, the research coordinator weighs participants, dispenses the study medication in blister packs, and assesses adherence by counting remaining medication doses from the previous month’s blister pack.

2.3 Rationale for the promotora-led lifestyle intervention

Our behavioral intervention uses community health workers (hereafter called promotoras and promotores, as they are often called in Latino populations) to deliver an adaptation of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) lifestyle program. There is robust evidence that promotores can be trained to deliver diverse health promotion and disease prevention interventions, especially in Latino communities.25,26 Because promotores are members of the target populations they serve, this intervention model has inherent cultural salience.27 Their experiential knowledge of participants’ social and cultural context gives promotores a unique position to help influence health behaviors in the community setting. For these reasons, experts consider promotores as an important strategy for reducing health disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups, such as the diabetes disparities observed among Latinas.28

A growing body of research has used promotores to deliver the DPP lifestyle intervention in diverse population groups including whites, African Americans, Latinos, and Asians/Pacific Islanders.29–33 However, none of these studies has focused exclusively on Latinas. A recent meta-analysis of DPP translation studies reported a pooled mean weight loss of 3.99% from baseline to 12 months, which was slightly lower for those using promotores as the interventionists (3.15%).9 The most successful DPP translations delivered by promotores reported 12-month weight loss approaching or exceeding the 7% goal used in the original DPP trial.29,33 A single-arm trial of our promotora-led DPP adaptation among Latinas with prediabetes demonstrated a 12-month weight loss of 5.6%.34 Our intervention, like many similar translational studies of the DPP, is delivered in the group setting because this approach capitalizes on the potentially therapeutic nature of group interactions35 and is presumed to be cost-effective.36 The rationale for the content and key features of the DPP lifestyle intervention have been described in-depth previously.37

2.3.1 Translation and description of the promotora-led lifestyle intervention

Our promotora-led DPP intervention is based on the Group Lifestyle Balance (GLB) program, which is an evidence-supported adaptation of the original National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases-supported Diabetes Prevention Program (copyright 2008, 2010, 2011; University of Pittsburgh).38 This program was developed by experts at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, in collaboration with the DPP Interventions Committee, and its development is described in-depth elsewhere.37 The year-long GLB program consists of 22 sessions focused on the same primary goals of the original DPP lifestyle intervention (7% weight loss and 150 minutes per week of physical activity), while using behavioral strategies such as problem solving to improve health behaviors and thereby achieve these goals. The core phase of the GLB program is delivered in 12 weekly sessions, followed by 10 maintenance sessions that reinforce the same content and focus on continuing healthy lifestyle changes.

Our promotora-led protocol was developed by making minimal modifications to the Spanish language GLB participant handouts, which are publicly available in their entirety.39 Prior to modifying the GLB materials, we conducted formative research suggesting fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages as specific dietary targets prevalent in the target population.12,40 In a qualitative study of Latinas with prediabetes, we identified social and cultural factors, such as changes in family roles and food preparation practices that participants believed to be related to their diabetes risk.12 Based on these findings, we developed culturally-appropriate dietary self-monitoring tools and targeted messages about healthy behavior change in the Latino family context that were incorporated into the protocol. (Appendix 1) This process of adapting the GLB protocol was also informed by feedback on the intervention materials given by the promotoras. As a result, we divided the second and third GLB sessions, which include detailed nutrition content, into four separate sessions to increase the time available for teaching this foundational material. Therefore, our promotora-led lifestyle intervention consists of 24 sessions over 12 months—14 weekly core sessions followed by 10 maintenance sessions. The first 4 maintenance sessions occur biweekly and the remainder take place monthly. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Promotora-Led Lifestyle Intervention Session Schedule

| Session # | Session Title | Wek Delivered |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Welcome and Getting Started | 1 |

| 2 | Be a Fat and Calorie Detective (Part 1) | 2 |

| 3 | Be a Fat and Calorie Detective (Part 2) | 3 |

| 4 | Healthy Eating (Part 1) | 4 |

| 5 | Healthy Eating (Part 2) | 5 |

| 6 | Move Those Muscles | 6 |

| 7 | Tip the Calorie Balance | 7 |

| 8 | Take Charge of What’s Around You | 8 |

| 9 | Problem Solving | 9 |

| 10 | Four Keys to Healthy Eating Out | 10 |

| 11 | The Slippery Slope of Lifestyle Change | 11 |

| 12 | Jump Start Your Activity | 12 |

| 13 | Make Social Cues Work for You | 13 |

| 14 | Ways to Stay Motivated | 14 |

| 15 | Long Term Self-Management | 16 |

| 16 | More Volume, Less Calories | 18 |

| 17 | Balance Your Thoughts | 20 |

| 18 | Strengthen Your Exercise Program | 22 |

| 19 | Mindful Eating | 26 |

| 20 | Stress and Time Management | 30 |

| 21 | Standing Up for Your Health | 34 |

| 22 | Healthy Heart | 38 |

| 23 | Stretching: The Truth about Flexibility | 42 |

| 24 | Looking Back and Looking Forward | 46 |

One promotora leads each 90-minute session in Spanish to groups of 6–10 participants, providing information on the weekly topic and using behavioral strategies, such as goal setting and problem solving, to discuss lifestyle behaviors. The promotora and participants spend the first half of each session reviewing goals from the previous session, and engaging in facilitated discussion about their experience meeting these goals. In the second half of each session, the promotora covers new content and helps participants set the following week’s goals. Participants are instructed to record their daily dietary intake and physical activity in weekly logs. A second promotora provides logistical support during each session, with responsibilities including weighing participants, collecting health behavior logs, and distributing written materials.

2.3.2 Selection and training of the promotoras

The 4 promotoras delivering this intervention were initially recruited by the partner organization and study site (Puentes de Salud, www.puentesdesalud.org) based on referrals from their board members and other leaders serving the same community. The Puentes de Salud health and wellness center developed its promotora outreach program in 2007, and has continuously operated diverse promotora-led interventions since then. This organization used the following criteria to select the promotoras: high school completion, Spanish language fluency, natural leadership skills, and commitment to serving their community. The promotoras are employees of Puentes de Salud and are paid $14/hour for their time spent training, preparing, and delivering the study sessions.

To participate in the current study, the promotoras received training from local and national diabetes prevention experts. First, they received 18 hours of training on the GLB protocol from the University of Pittsburgh Diabetes Prevention Support Center. The director of the partner organization’s promotora program (VAA) attended an additional 2-day training on diabetes prevention from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Diabetes Prevention Program.41 After completing these training events with national content experts, the promotoras delivered all 24 sessions to members of the investigative team (MJO, VAA) using our Spanish translation of the English language GLB trainers’ guide. Our investigators provided feedback to the promotoras on both the content and the manner in which it was covered. This phase of the promotoras’ training lasted approximately 50 hours (2 hours per session) over a 2-month period. Puentes de Salud’s promotora director (VAA) provides ongoing supervision to the promotoras and answers their questions that arise during implementation of the study.

2.4 Description of the standard care intervention

Participants in the standard care arm complete two study visits during months 3 and 9, in which the study coordinator obtains their weight and distributes standardized educational materials on diabetes prevention from the National Diabetes Education Program (NDEP).42 The research coordinator briefly orients participants to these NDEP materials without discussing them at length. Because of the infrequent counseling that individuals with prediabetes receive from their regular healthcare providers,43 we designed the standard care intervention to be at least as intensive as Latinas with prediabetes might otherwise receive in routine clinical encounters. Participants in the standard care group did not receive a placebo pill.

2.5 Recruitment and screening

Participants were recruited in both community and clinical settings between November 2013 and March 2015. We recruited potential participants during health fairs and other large community events organized by Latino-serving nonprofits in Philadelphia. The study team conducted initial screening activities at a table dedicated for this purpose. Latinas who expressed interest in the study were asked to complete the American Diabetes Association’s seven-item Diabetes Risk Assessment Questionnaire.44 Those with a risk score of four or greater were considered high-risk and subsequently underwent fasting lab work at Temple University’s Center for Obesity Research and Education to determine their eligibility.

In addition, recruitment efforts were conducted at the Puentes de Salud community health center and three other primary care clinics serving the target population. In these clinical settings, potential participants’ eligibility was determined by review of their electronic health records after obtaining approval from their primary care provider. Latinas meeting demographic and clinical study criteria were invited to Temple University’s Center for Obesity Research and Education to conduct final eligibility screening, which included assessment of fasting plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1C if their last clinical measurement was performed more than 6 months before. The screening visit also included determination of potential exclusion criteria by physician study team members (MJO, CMM).

2.6 Outcomes and data collection

At the enrollment visit, each participant completed a baseline survey in Spanish and a cardiometabolic assessment. The same procedure is followed at 6 and 12 months for outcome assessments. Research assistants were trained by the principal investigator (MJO) and research coordinator (AP) to collect all study data at the Temple University Center for Obesity Research and Education. The primary outcome is the between-group difference in body weight from baseline to 12 months. Weight loss was chosen as the primary outcome because the reduction in diabetes incidence observed with both intensive lifestyle intervention and metformin in the DPP was principally mediated by this mechanism.45,21 The primary outcome is assessed at 12 months to examine the extent to which weight loss is sustained beyond participants’ high interest level and intensive participation early in the study.46 Body weight is measured to the nearest 0.1kg using a Detecto high capacity digital scale. To allow for calculation of BMI, height is measured twice to the nearest 1mm using a Holtain wall-mounted stadiometer, and reported as the average of the 2 values. Secondary outcomes are described below.

Participants’ weight is used to determine the percentage of participants in each group achieving at least 5% weight loss, which is associated with diverse cardiometabolic improvements, including reduction in glycemic markers.47 Waist circumference is assessed using a measuring tape around the top of the iliac crests at end-expiration, and recorded as the average of two values. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure are measured using a GE Dinamap anaeroid sphygmomanometer with participants seated for five minutes prior. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure are also recorded as the average of two measured values. Venipuncture is performed by a licensed phlebotomist for assessment of hemoglobin A1C, fasting plasma glucose, insulin and lipids (total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides). All plasma specimens are collected after a minimum fast of 8 hours, and are analyzed in the same Quest Diagnostics laboratory that meets the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program requirements.48 Physical activity is objectively assessed at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months using Actigraph GT3X accelerometers worn continuously for 1 week.

The participant survey assesses sociodemographic characteristics and basic self-reported clinical information, including personal history of gestational diabetes and family history of diabetes in a first-degree relative. In addition, we are measuring the following psychosocial covariates with widely-used instruments that have been validated in Spanish-speaking populations: health literacy49 (Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, α = 0.97), health-related quality of life50 (Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, α = 0.90), acculturation51 (Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics, α = 0.92), social support52 (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, α = 0.88), perceived stress53 (Perceived Stress Scale, α = 0.85), depression54 (Beck Depression Inventory, α = 0.91), and anxiety55 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder -7 scale, α = 0.92).

While we plan to calculate costs associated with each of the 3 study interventions, we do not plan to conduct formal cost-effectiveness analyses.

2.7 Sample size

The PREVENT-DM sample size was determined for the primary outcome (between-group difference in weight loss) at 12-month follow-up with power ≥0.80 and ɑ=0.05. Preliminary estimates drawn from a pilot study with the same population indicate that at least 90% of enrolled participants would be retained to follow-up.34 These pilot data also demonstrated a standard deviation of 10.7lbs for weight loss; and we estimated the correlation between occasions to be ≥0.80. Based on these assumptions, we aimed to enroll 30 individuals per study arm and retain 27 in each group at follow-up. Under these circumstances, we expect to detect weight loss of at least 4.2 lbs.

2.8 Randomization

We used a randomized permuted block design with varying block lengths to assign participants to the 3 treatment arms. This method achieves balanced allocation of participants among treatment groups while increasing the randomness of assignments by varying block sizes. The assignment for each randomized group was concealed in individually-sealed, opaque envelopes kept in a locked filing cabinet accessible only to the research coordinator, who ultimately assigned participants to the study interventions. The nature of the study interventions precludes blinding participants, promotoras, or the research coordinator to treatment assignments. The study partner organization, Puentes de Salud, expressed concern about randomizing participants to a standard care group given the known efficacy of lifestyle intervention and metformin among adults with prediabetes. To address this concern, all standard care participants are offered the lifestyle intervention after completing their 12-month assessment. In addition, all standard care participants are encouraged to discuss with their regular healthcare providers whether they should take metformin as a diabetes prevention treatment after completing the study.

2.9 Statistical analyses

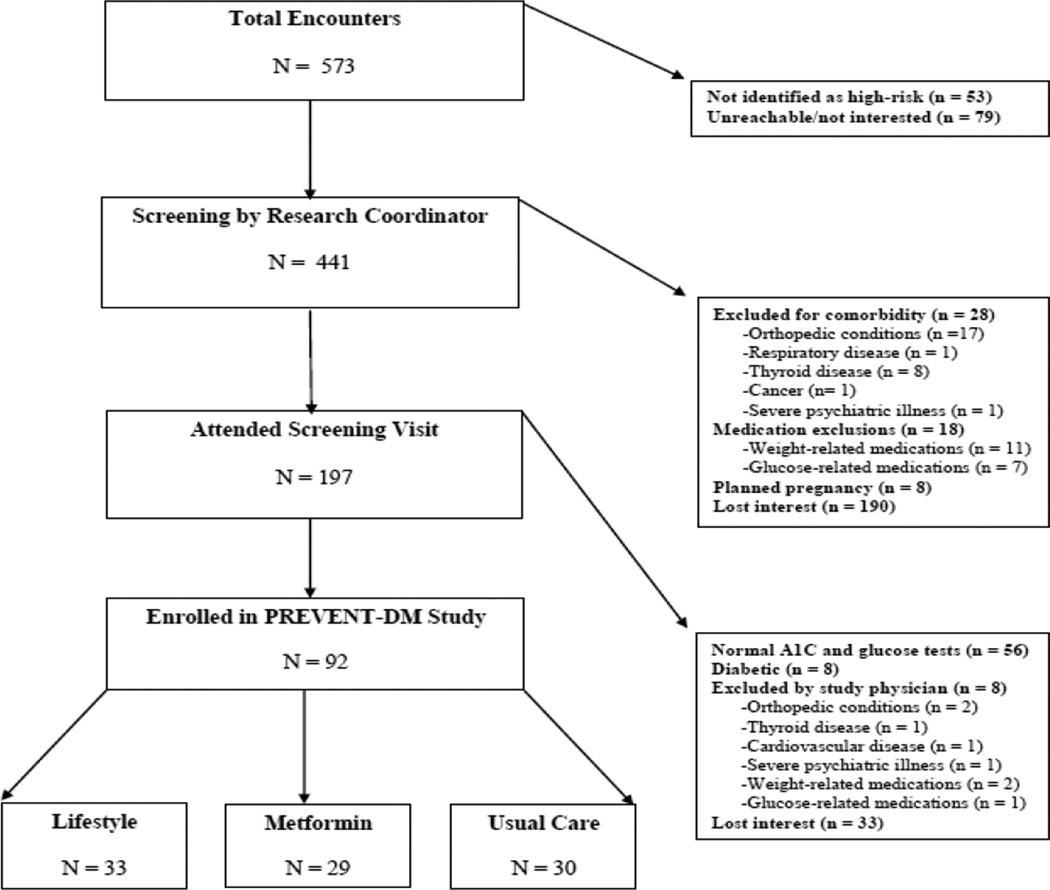

Analyses for this manuscript include descriptive statistics summarizing the participant flow (Figure 1), in addition to the baseline characteristics of the study cohort (Table 3). For each participant characteristic, we present the mean value in the full study cohort, in addition to the means within each randomized study arm. For dichotomous self-reported factors, such as family history of diabetes, the proportion of participants reporting each factor is presented among the full study sample, and then separately by treatment arm. Baseline differences in participant characteristics across the 3 treatment arms were examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables.

Figure 1. Trial flow.

Boxes and arrows indicate the flow of potentially eligible participants as deemed approachable, eligible, enrolled, and randomized; side arrows provide reasons for ineligibility and non-enrollment.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the PREVENT-DM cohort by randomized treatment group

| Characteristic | Overall (n=92) |

Lifestyle (n=33) |

Metformin (n=29) |

Standard care (n=30) |

P- valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45.1 ± 12.5 | 45.5 ± 12.3 | 45.8 ± 11.7 | 44.0 ± 13.6 | 0.83 |

| Education, years | 9.7 ± 3.6 | 10.2 ± 3.5 | 9.5 ± 3.6 | 9.2 ± 3.7 | 0.59 |

| Household income, dollars | 15,527 ± 9,922 | 14,905 ± 7,518 | 17,315 ± 11,293 | 14,482 ± 10,894 | 0.50 |

| Foreign born, n (%) | 86 (93.5) | 30 (90.9) | 26 (89.7) | 30 (100) | 0.21 |

| Duration of U.S. residence, years | 18.2 ± 13.0 | 20.3 ± 13.3 | 17.8 ± 14.2 | 16.5 ± 11.7 | 0.51 |

| Family history of diabetes, n (%) | 65 (70.7) | 25 (75.8) | 21 (72.4) | 19 (63.3) | 0.54 |

| History of gestational diabetes, n (%) | 18 (19.6) | 9 (27.2) | 6 (20.7) | 3 (10.0) | 0.22 |

| Weight, lbs | 178.8 ± 39.3 | 188.0 ± 50.5 | 175.3 ± 28.6 | 172.0 ± 32.9 | 0.23 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.3 ± 6.5 | 34.4 ± 7.9 | 33.2 ± 5.5 | 32.2 ± 5.7 | 0.39 |

| Hemoglobin A1C, % | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 0.68 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 96.1 ± 9.5 | 97.5 ± 7.5 | 94.6 ± 10.1 | 96.0 ± 10.7 | 0.46 |

| Insulin, µIU/mL | 10.4 ± 5.7 | 10.4 ± 5.8 | 10.6 ± 5.5 | 10.2 ± 6.0 | 0.97 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 97.4 ± 11.1 | 101.4 ± 13.0 | 95.6 ± 9.1 | 94.9 ± 9.8 | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 119.6 ± 17.0 | 118.4 ± 13.9 | 122.2 ± 19.8 | 118.3 ± 17.6 | 0.61 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 74.5 ± 9.6 | 74.5 ± 9.8 | 75.9 ± 10.2 | 73.3 ± 9.0 | 0.57 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 186.6 ± 37.0 | 192.8 ± 34.8 | 186.2 ± 43.6 | 180.3 ± 32.3 | 0.41 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 110.3 ± 32.3 | 114.3 ± 30.6 | 110.7 ± 38.8 | 105.6 ± 27.4 | 0.57 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 51.0 ± 12.2 | 49.5 ± 13.2 | 52.2 ± 10.7 | 51.3 ± 12.8 | 0.69 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 125.1 ± 56.9 | 144.6 ± 73.7 | 110.6 ± 30.5 | 117.6 ± 50.6 | 0.04 |

Data are presented as means ± SD or n (%).

Tests of significance were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for dichotomous variables.

Future manuscripts will report on the 12-month study outcomes, including weight loss (primary) and changes in other cardiometabolic markers (secondary). Data will be analyzed assuming an intent-to-treat approach where all randomized subjects are analyzed according to their treatment assignment, regardless of adherence. Mean differences in outcomes between treatment groups will be evaluated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models adjusted for baseline measurement and other relevant covariates associated with the outcomes. Multiple imputation methods56,57 and model-based analyses with direct maximum likelihood methods58 will be used to account for missing data and conduct sensitivity analyses. All analyses will be conducted using Stata 14. (College Station, TX)

3. RESULTS

3.1 Participant flow metrics

During the 17-month recruitment period, we approached 573 Latinas to assess their potential interest and eligibility to participate in PREVENT-DM. Most were identified in clinic sites (n=389, 68%), and the remainder in community settings (n=184, 32%). Of those approached by the study team, only 53 (9%) were not initially considered at high risk for developing diabetes based on the ADA Diabetes Risk Assessment Questionnaire.44 Among the remaining 441 Latinas initially identified as high-risk, the most common reason for not enrolling in the study was losing interest. This was the case for 223 women (50.6%) during the entire eligibility screening process. Sixty four potential participants were excluded because their fasting plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1C were outside the prediabetic range, the majority of whom were normoglycemic by both tests (n=56). Only 8 women were found to have diabetes, at which point they were referred to their primary care providers with a copy of their lab results for medical management. Exclusions were also made based on the presence of other comorbidities (n=33), most commonly orthopedic conditions (n=19), or exclusionary medications (n=21). A minority of participants were excluded because they were planning to get pregnant during the study period (n=8). Over the entire recruitment period, we enrolled and randomized 92 participants out of the 441 initially found to be at high risk (20.9%). Seventy-eight PREVENT-DM participants were recruited from clinic partner sites (85%) and 14 from community-based venues (15%).

3.2 Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort

The baseline characteristics of the PREVENT-DM cohort are displayed in Table 3. Participants were middle-aged, Spanish-speaking Latinas with low levels of educational attainment and household income. Nearly all participants were foreign born, with the majority coming from Mexico (45%), Puerto Rico (24%), or the Dominican Republic (12%). Most participants had a sibling or parent with diagnosed diabetes, and approximately 20% percent had gestational diabetes during a previous pregnancy. While the sample, on average, had obesity (BMI ≥30kg/m2), abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥88cm),59 and prediabetes, PREVENT-DM participants had normal mean levels of other cardiometabolic markers at baseline, including blood pressure, fasting lipids, and insulin levels. Although all participants had prediabetes by A1C and/or fasting plasma glucose criteria, more participants qualified for the study based on A1C alone (58%, data not shown). This resulted in a mean fasting plasma glucose level below the diagnostic threshold of 100mg/dL.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The PREVENT-DM study successfully recruited and randomized 92 Latinas with prediabetes to receive a promotora-led lifestyle intervention based on the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), metformin, or standard care. Compared to previously-published translational trials of the DPP,60,61 our screening process yielded a similar proportion of study participants from those initially approached. Also consistent with the previous translational literature, we found that referrals from participating clinic sites had a higher yield than community-based recruitment activities.61,62 Although the PREVENT-DM recruitment process was less efficient relative to the DPP and other translational trials,6,29,60 this is likely explained by resource limitations in the current study that permitted only 1 full-time staff member (AP).

For several reasons, the PREVENT-DM study is positioned to make contributions to the diabetes prevention field. PREVENT-DM is the first translational trial of the DPP to include only Latinas, the demographic group at highest risk for diabetes. Our study population is also unique with respect to its socioeconomic disadvantage and Spanish-speaking status—both factors that complicate recruitment and retention in clinical trials, and are therefore under-represented among participants in the existing literature.63 Second, the promotora-led lifestyle intervention studied here is an emerging model for community-based diabetes prevention that is both culturally appropriate in the target population and potentially scalable given its low costs relative to delivery by certified professionals.64 As national and state-level funding initiatives that support lay health workers evolve,65 evidence for the effectiveness of a promotora-led diabetes prevention model may inform future health payer coverage decisions that could enhance its sustainability. In addition, PREVENT-DM is the first study in the U.S. to compare the effectiveness of intensive lifestyle intervention and metformin to standard care in a “real-world” setting. Whereas the DPP demonstrated the comparative efficacy of delivering an intensive lifestyle intervention versus metformin within a subgroup of highly-motivated Latino clinical trial volunteers, PREVENT-DM will determine the comparative effectiveness of these interventions when offered to more typical Latina adults using pragmatic and scalable delivery channels.

While the DPP and other efficacy trials have reported weight loss and reduced diabetes incidence with metformin relative to placebo, this treatment has not been studied in community-based sample of adults with prediabetes in the U.S. Previous translational research in diabetes has demonstrated that treatments delivered in pragmatic contexts often achieve smaller effects than highly controlled efficacy studies.66 Indeed, translational studies of the DPP lifestyle intervention in community settings have found lower effectiveness on weight loss and glycemic outcomes than was originally reported in the efficacy trial.9,67 By testing the effectiveness of metformin and intensive lifestyle intervention versus standard care in a pragmatic setting, PREVENT-DM addresses an unanswered question in the diabetes prevention literature with significant public health implications. The inclusion of only Latinas in this trial limits the generalizability of the findings to this specific, but large high-risk population.

Preventing diabetes among high-risk adults presents significant challenges. Nearly 1/3 of U.S. adults have prediabetes,1 yet only 10% of those affected are aware of their diagnosis.68 Intensive lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes require a high level of participant engagement, and current capacity to deliver such programs at a national scale is inadequate to meet the population demand.69 Healthcare providers do not uniformly offer lifestyle counseling to patients with prediabetes;70 and they prescribe metformin even less frequently.71,72 In this context, we anticipate that the PREVENT-DM study will contribute to a large body of translational diabetes prevention research, providing evidence to guide treatment decisions between individuals with prediabetes and their healthcare providers. Such evidence may also inform large-scale research comparing these diabetes prevention treatments and testing strategies for delivering them most effectively in real-world settings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Diabetes Prevention Support Center (DPSC) of the University of Pittsburgh for training and support in the Group Lifestyle Balance Program; the current program is a derivative of this material. In particular, we would like to thank Elizabeth Venditti, PhD for her role in training our group and her ongoing support during implementation of the lifestyle intervention. We acknowledge the four promotoras delivering the lifestyle intervention in this study: Irma Zamora, Amarili Lopez, Rosalinda Hernandez, and Fabiola Carrasco. We would also like to thank the following people for their essential roles in implementing PREVENT-DM: Carol Homko, PhD; Barbara Schneider, MD; Michelle Nashleanas, MD; and Gonzalo Romero, MD. We are grateful for the many efforts of dedicated volunteers who helped with various aspects of the study. We would like to thank Maria Vargas, MPH for her help in preparing the manuscript for publication. Finally, we would like to recognize the PREVENT-DM participants for their time and dedication to this study. This study is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23-DK095981, O’Brien PI). We would also like to acknowledge other funders of this program, including the Kynett Foundation, the Claneil Foundation, and the Connelly Foundation. The funders played no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.The Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates and Its Burden in the United States. Vol. 2014. Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Gregg EW, Williamson DF, et al. A1C level and future risk of diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1665–1673. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the US population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):287–294. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1884–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krogstad JM, Lopez MH. Hispanic nativity shift: US births drive population growth as immigration stalls. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center's Hispanic Trends Project; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowler W, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler S, et al. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lidestyle Intervention or Metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan XR, Li G, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance: the Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(4):537–544. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(1):67–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, et al. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1) Diabetologia. 2006;49(2):289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien MJ, Whitaker RC, Yu D, Ackermann RT. The comparative efficacy of lifestyle intervention and metformin by educational attainment in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Prev Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien MJ, Shuman SJ, Barrios DM, Alos VA, Whitaker RC. A Qualitative Study of Acculturation and Diabetes Risk Among Urban Immigrant Latinas: Implications for Diabetes Prevention Efforts. Diabetes Educator. 2014;40(5):616–625. doi: 10.1177/0145721714535992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miranda AO, Bilot JM, Peluso PR, Berman K, Van Meek LG. Latino Families: The Relevance of the Connection Among Acculturation, Family Dynamics, and Health for Family Counseling Research and Practice. Fam J. 2006;14(3):268–273. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez SM, Arredondo EM, Perez G, Baquero B. Individual, social, and environmental barriers to and facilitators of physical activity among Latinas living in San Diego County: focus group results. J Fam Health. 2009;32(1):22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000342814.42025.6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Supplement 1):S8–S16. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vella CA, Burgos X, Ellis CJ, et al. Associations of insulin resistance with cardiovascular risk factors and inflammatory cytokines in normal-weight Hispanic women. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1377–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HAW. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1577–1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34) The Lancet. 1998;352(9131):854–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Effects of withdrawal from metformin on the development of diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(4):977–980. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Kahn JA, Salpeter EE. Meta-analysis: metformin treatment in persons at risk for diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):149–157. e142. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachin JM, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al. Factors associated with diabetes onset during metformin versus placebo therapy in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes. 2007;56(4):1153–1159. doi: 10.2337/db06-0918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability, and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:731–737. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoeger KM, Kochman L, Wixom N, et al. A randomized, 48-week, placebo-controlled trial of intensive lifestyle modification and/or metformin therapy in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(2):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.02.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng EHY, Wat NMS, Ho PC. Effects of metformin on ovulation rate, hormonal and metabolic profiles in women with clomiphene-resistant polycystic ovaries: a randomized, double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(8):1625–1631. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.8.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zometa CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: a qualitative systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(5):418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA, Larson SC. Role development of community health workers: an examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6) Suppl 1:S262–S269. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenthal EL, Brownstein JN, Rush CH, et al. Community health workers: part of the solution. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(7):1338–1342. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez LM, Martinez J. Community health workers: social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parikh P, Simon EP, Fei K, et al. Results of a pilot diabetes prevention intervention in East Harlem, New York City: Project HEED. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S232–S239. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mau MK, Keawe'aimoku Kaholokula J, West MR, et al. Translating diabetes prevention into native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities: the PILI 'Ohana Pilot project. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(1):7–16. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faridi Z, Shuval K, Njike VY, et al. Partners reducing effects of diabetes (PREDICT): A diabetes prevention physical activity and dietary intervention through African-American churches. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(2):306–315. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katula JA, Vitolins MZ, Rosenberger EL, et al. One-year results of a community-based translation of the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1451–1457. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien MJ, Perez A, Alos VA, et al. The feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of a promotora-led diabetes prevention program (PL-DPP) in Latinas: a pilot study. Diabetes Educ. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0145721715586576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heshka S, Anderson JW, Atkinson RL, et al. Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1792–1798. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katula JA, Vitolins MZ, Rosenberger EL, et al. Healthy Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes (HELP PD): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer MK, Kriska AM, Venditti EM, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program: a comprehensive model for prevention training and program delivery. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.University of Pittsburgh. Diabetes Prevention Support Center. [Accessed February 6, 2015]; http://www.diabetesprevention.pitt.edu/. [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Brien MJ, Davey A, Alos VA, Whitaker RC. Diabetes-related behaviors in Latinas and non-Latinas in California. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):355–361. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Coach and Master Training. [Accessed July 29, 2015];2015 http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/training.htm.

- 42.National Diabetes Education Program. Publications. [Accessed July 15, 2015];2014 http://ndep.nih.gov/publications/index.aspx.

- 43.Geiss LS, James C, Gregg EW, et al. Diabetes risk reduction behaviors among U.S. adults with prediabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Diabetes Association. American Diabetes Association. Alexandria, VA: 2011. Diabetes Risk Test. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2102–2107. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis LL, Broome ME, Cox RP. Maximizing retention in community-based clinical trials. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring Md.) 2006;14(5):737. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Little RR. Glycated hemoglobin standardization–National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) perspective. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41(9):1191–1198. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2003.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):537–541. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983:385–396. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13072/midss.461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder - The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Collins LM, Sayer AG. New methods for the analysis of change. American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. CRC press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molenberghs G, Kenward M. Missing data in clinical studies. Vol. 61. John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Schmidt KK, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of a community-based comparative effectiveness trial to prevent type 2 diabetes in economically disadvantaged adults: The RAPID Study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blackwell CS, Foster KA, Isom S, et al. Healthy Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes: recruitment and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lovato LC, Hill K, Hertert S, Hunninghake DB, Probstfield JL. Recruitment for controlled clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Control Clin Trials. 1997;18(4):328–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Jr, Genel M, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289(10):1278–1287. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown HS, 3rd, Wilson KJ, Pagan JA, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a community health worker intervention for low-income Hispanic adults with diabetes. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E140. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Katzen A, Moran M. How Medicaid Preventive Services, Medicaid Health Homes, and State Innovation Models are Including Community Health Workers. Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation Harvard Law School; 2015. May 30, 2014, http://www.chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ACA-Opportunities-for-CHWsFINAL-8-12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garfield SA, Malozowski S, Chin MH, et al. Considerations for diabetes translational research in real-world settings. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(9):2670–2674. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dunkley AJ, Bodicoat DH, Greaves CJ, et al. Diabetes Prevention in the Real World: Effectiveness of Pragmatic Lifestyle Interventions for the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes and of the Impact of Adherence to Guideline Recommendations A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):922–923. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Awareness of prediabetes--United States, 2005–2010. MMWR. 2013;62(11):209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Registry of Recognized Programs. [Accessed October 19, 2015];2015 https://nccd.cdc.gov/DDT_DPRP/State.aspx?STATE=ALL.

- 70.Yang K, Lee YS, Chasens ER. Outcomes of health care providers' recommendations for healthy lifestyle among U.S. adults with prediabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011;9(3):231–237. doi: 10.1089/met.2010.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moin T, Li J, Duru OK, et al. Metformin prescription for insured adults with prediabetes from 2010 to 2012: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(8):542–548. doi: 10.7326/M14-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmittdiel JA, Adams SR, Segal J, et al. Novel use and utility of integrated electronic health records to assess rates of prediabetes recognition and treatment: brief report from an integrated electronic health records pilot study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(2):565–568. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.