Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is associated with increased risk of multiple neoplasms. We present a case of a female patient with NF1 who presented with a rectal low-grade neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumor. Computed tomography imaging found a well-differentiated liposarcoma and a well-circumscribed gastro-intestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Although GIST and carcinoid tumors are frequently found in NF1 patients, liposarcoma complicating NF1 is quite rare and this is the first reported case of well-differentiated liposarcoma in NF1. In summary, we report a case of coincident abdominal carcinoid tumor, GIST and well-differentiated liposarcoma, which illustrates the variability of neoplasms in NF1 patients.

Keywords: Well-differentiated liposarcoma, GIST, Carcinoid, Type 1 neurofibromatosis, Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

1. Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic disease, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 2500–3000 live births.1 It is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder with variable penetrance, and is caused by a wide array of mutations in the neurofibromatosis (NF1) gene on chromosome 17. Although neurofibromas are the hallmark of the disease, NF1 patients are at increased risk for the development of neural, mesenchymal and neuroendocrine tumors, among others2, 3 (see also4 for a review). The clinical severity of NF1 is variable and indicates that phenotypic expression is determined through modifier genes.5, 6, 7 Multiple malignant mesenchymal tumors, or sarcomas, have been reported in NF1, of which malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) is by far the most common.8 Liposarcoma (LPS) arising in NF1 patients is very rare.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 It is most often pleomorphic, dedifferentiated or myxoid type. In fact, a case of well-differentiated liposarcoma in NF1 has, to our knowledge, never been reported.

Here, we report an unusual case of a patient with a clinical history of NF1 and three coincident abdominal tumors: a low-grade neuroendocrine tumor of the rectum, a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the small bowel serosa, and a well-differentiated liposarcoma of the small bowel mesentery. This unusual case highlights the spectrum of mesenchymal tumors in NF1, and the first case of well-differentiated liposarcoma.

2. Case presentation

A 55-year-old female with NF1 presented with mild rectal bleeding and a history of a prior rectal ‘polyp.’ The patient had a long-standing diagnosis of NF1, and disease manifestations including numerous cutaneous neurofibromas and mild cognitive deficits. Four years previously, the patient had a 2.5 cm bleeding rectal polyp. This was removed by transanal excision and diagnosed as a low-grade neuroendocrine tumor (performed at an outside hospital with pathology unavailable for review). Margin status of the original excision was not reported. Sigmoidoscopy at this time showed mucosal nodularity at the prior excision site. The patient then underwent sigmoidoscopy directed biopsy.

The biopsy specimen consisted of small fragments of rectal mucosa and submucosa. H&E staining of the biopsy showed small foci of round neoplastic cells arranged in an insular pattern, involving the submucosa (Fig. 1A). Tumor cells showed moderate amounts of finely granular cytoplasm, and characteristic ‘salt and pepper’ chromatin. Tumor cells exhibited no significant nuclear pleomorphism, no mitoses and no necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed the neuroendocrine differentiation of neoplastic cells, with positivity for Synaptophysin and Chromogranin (Fig. 1B). Ki67 labeling index was low, estimated as less than 1% of tumor cells (Fig. 1C). A diagnosis of recurrent, well-differentiated, low-grade neuroendocrine tumor was rendered.

Fig. 1.

Histological appearance of rectal low-grade neuroendocrine tumor. (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) microscopic appearance of the rectal mass demonstrates nests of neoplastic cells in the submucosa. (B) Immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers Synaptophysin (not shown) and Chromogranin (CG). (C) Immunohistochemical staining found a low Ki67 labeling index, indicating a well-differentiated tumor. Histology images were taken at 400×.

An interim abdominal CT scan was performed in order to evaluate tumor progression. This contrast enhanced CT scan demonstrated two additional incidental intra-abdominal masses (Fig. 2). No definitive increase in thickness of the rectal wall was identified. The first tumor was a partially enhancing, infiltrative lipomatous mass found within the small bowel mesentery. The mass measured 3.9 cm in greatest dimension and partially encased the superior mesenteric vessels. The second tumor was a well-circumscribed, enhancing 1 cm nodule within the mesentery of the jejunum. The patient underwent a CT-guided biopsy of the lipomatous tumor, which revealed a low-grade lipomatous proliferation with adipocytes of varying size. The histology from the biopsy demonstrated myxoid degeneration containing focally hypercellular aggregates of atypical, hyperchromatic stromal cells and focal floret-like giant cells (Fig. 3A). S100 immunohistochemistry was partially positive (Fig. 3B), while CD117 (CKIT) and DOG1 were negative. Mitoses or atypical mitotic figures were not seen. Cytogenetic analysis found evidence of MDM2 gene amplification, and a pathological diagnosis of well-differentiated liposarcoma was rendered. Given the unusual presentation and rarity of liposarcoma in NF1, plans for an open biopsy, versus possible excision if resectable, were made. Intraoperatively, the tumor was intimately associated with the superior mesenteric vessels, precluding complete resection. Pathologic examination of a 3.5 cm partial resection specimen yielded identical findings, consistent with well-differentiated liposarcoma. No de-differentiated component or adjacent neurofibromatosis tissue was identified.

Fig. 2.

CT images of gastrointestinal stromal tumor and liposarcoma. (A) Coronal image through the abdomen demonstrates an infiltrative mixed soft tissue and fat density mass (white arrows). As well, a discrete enhancing nodule within an adjacent loop of jejunum (small black arrows) was observed. (B) Axial image through the abdomen demonstrates the same mixed soft tissue and fat density infitrative tumor anterior to the superior mesenteric artery (white arrows). (C) Enhancing small nodule (black arrow) within wall of bowel.

Fig. 3.

Histological appearance of well-differentiated liposarcoma of the small bowel mesentery. Adipocytes of varying sizes contain spindle cells with large deeply stained nuclei. (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) histology illustrate fibrous tissue with myxoid degeneration and floret-like giant cells. (B) Immunohistochemistry was partially positive for S100 staining. Histology images were taken at 100× and 400×.

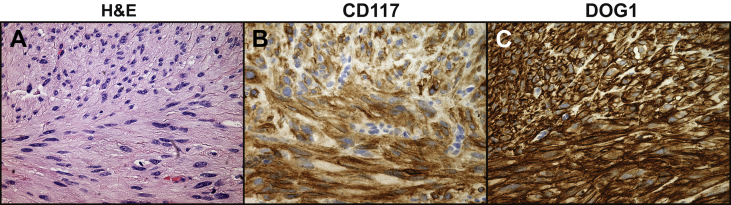

During surgical exploration of the lipomatous mass, the nodule on the jejunal serosa was identified and completely resected. When assessed histologically, the excisional biopsy demonstrated a relatively bland, circumscribed proliferation of plump spindle cells (Fig. 4A). These cells were arranged in loose intersecting fascicles in a hyalinized stroma. Focal nuclear palisading and scattered areas of epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei were seen. The cells lacked mitotic activity. Immunohistochemistry for CD117 (Fig. 4B) and DOG1 were diffusely positive (Fig. 4C). CD34 immunostaining was focally positive, and a diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) was made.

Fig. 4.

Histological appearance of the gastrointestinal tumor (GIST) from the small bowel. (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining demonstrated demonstrated spindled to epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and variably hyalinized stroma and skenoid fibers. Immunohistochemistry found positive (B) CD117 (CKIT) and (C) DOG1 staining. Histology images were taken at 400×.

Postoperatively, a decision was made in conjunction with the patient and family to undergo clinical and imaging surveillance for her tumors. No additional treatment was recommended for her recurrent neuroendocrine tumor, given its small size, low histologic grade, and low probability of progression. Likewise, no additional treatment was recommended for her GIST, given the benign course of the small GISTs among NF1 patients.16 Finally, in regards to her well-differentiated LPS, radiotherapy was not recommended as no areas suspicious for de-differentiation were identified on CT. Clinical follow up at 2 months showed no evidence of disease progression.

3. Discussion and literature review

In summary, we present a patient with NF1 complicated by three coincident abdominal tumors: a rectal carcinoid tumor, a gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the jejunal serosa, and a mesenteric well-differentiated liposarcoma. Given the rarity of LPS in NF1 patients, the diagnosis was confirmed by two separate biopsy specimens as well as FISH-identified MDM2 amplification. This extremely unusual case highlights the diverse tumors encountered in NF1. In subsequent sections, we will discuss both the incidence and clinical features of LPS, carcinoid and GIST specific to NF1 patients. As well, the competing diagnosis of liposarcoma versus the more probable lipomatous/liposarcomotous differentiation within peripheral nerve sheath tumors will be discussed.

3.1. Liposarcoma in neurofibromatosis

Liposarcoma (LPS) in patients with NF1 is very unusual; our case represents the 10th reported case.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17 Of reported cases, 4/10 were pleomorphic LPS, 2/10 were myxoid LPS, 2/10 were dedifferentiated LPS, and one case was not subtyped. Our case represents the only example of well-differentiated LPS (1/10). Thus, the incidence of pleomorphic LPS would seem significantly more common in NF1 patients than in the general population (40% of LPS in NF1 patients as compared to approximately 5% of LPS in the general populace).18 In contrast, well-differentiated LPS seems less common in NF1 (10% of cases in NF1 as compared to 40–45% of cases in the general population).8, 19, 20 Both cases of dedifferentiated LPS arose ‘de novo,’ as is most typical.8, 19 Sites of involvement of LPS in NF1 are not dissimilar to the general population. The majority arose from the deep soft tissue of the extremities (4/10, 40%) or the retroperitoneum (3/10, 30%). One pleomorphic LPS reportedly arose from the soft tissue in the temporal region15; the scalp is a rare but previously reported site of involvement.21 Perhaps most importantly, a significant minority of cases (4/10, 40%) were felt to arise within or adjacent to a neurofibroma. As discussed in the following section, this may suggest an alternate diagnosis of lipomatous/liposarcomatous differentiation in peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Although clinical follow-up was limited in many cases (range: 4 weeks to 5 years), the clinical course was not dissimilar to LPS arising in non-NF1 patients, including local recurrence in 3/10 cases (30%). Unusual clinical manifestations of LPS in NF1 were reported. One of the earliest reports, from 1963, reported probable cerebral metastasis,15 this is exceedingly rare with dedifferentiated LPS as previous reports have shown that 4% of these patients develop brain metastases.22, 23 One recent patient is reported to have had an axillary lymph node metastasis,9 which would be an exceptionally rare route of metastatic spread for liposarcoma; this case report did not include histology images or results of molecular testing.23, 24, 25 In summary, a significantly increased rate of pleomorphic LPS is reported in NF1 patients, along with an increased number of cases of LPS arising adjacent to neurofibromatosis tissue. These factors suggest that lipomatous/liposarcomatous differentiation in peripheral nerve sheath tumors is a potential alternate diagnosis in these cases. Overall, the remaining cases do not show any definable dissimilarity in epidemiologic, pathologic or prognostic features from LPS in the general population.

3.2. Lipomatous/liposarcomatous differentiation in peripheral nerve sheath tumors

As mentioned, 4 of 10 cases of 'liposarcomas', all reported more than 30 years ago, were found to arise from or adjacent to neurofibromatosis tissue, bringing up the strong possibility of an alternate diagnosis of lipomatous/liposarcomatous differentiation within a peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Both benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are well known have heterogenous elements. In neurofibromas, diffuse fatty overgrowth may be seen and can even eclipse the neurofibromatosis tissue. In all four cases arising from neurofibromatosis tissue, the histologic description was that of highly atypical pleomorphic cells and focal lipoblast-like cells arising within or adjacent to more bland appearing neurofibroma tissue.10, 11, 15 In one case a myxoid stroma was reported,10 while in another case a malignant-appearing spindled population was noted.15 Under current diagnostic criteria, it is likely that these cases would have been interpreted as MPNST with liposarcomatous differentiation, given both the focality of the lipoblastic cells, and the classic MPNST-type histology in other tumor areas. Although rarely described, multiple cases of MPNST with liposarcomatous components have been observed.26, 27, 28 Overall, it is estimated that 10–15% of MPNST have heterologous components, including mature cartilage and bone.8, 29 Other reported heterologous elements include rhabdomyoblastic,30, 31 squamous8 and glandular,32 differentiation.

3.3. Neuroendocrine tumor/carcinoid in neurofibromatosis

The prevalence of carcinoid (neuroendocrine tumors) in NF1 patients is far greater than the general population, as incidence is estimated a 1% versus 0.001% in the general population.33, 34 Our patient had a recurring benign rectal neuroendocrine tumor. Only one case of a rectal carcinoid tumor in an NF1 patient has been previously reported.35 In NF1 patients, the most commonly reported neuroendocrine tumor is an ampullary carcinoid, which has been estimated to represent 25% of ampullary tumors in NF1 patients.36, 37 Many ampullary carcinoids in NF1 patients are somatostatinomas, but carcinoids of all types are seen. Interestingly, ampullary carcinoids are very rare outside of NF1. Mortality from carcinoids in NF1 is unusual, but most do metastasize.38

3.4. GIST in neurofibromatosis

NF1 patients are at increased risk for development of GISTs, with an estimated incidence of 7% in one study population.38 In NF1 patients, GISTs usually manifest at later ages, typically during middle age.39 In NF1, GISTs are characteristically multiple, small, mitotically inactive and have a spindle cell morphology.40, 41 They are typically located in the jejunum or ileum, and are in found in association with ICC hyperplasia.42, 43 The gross and histologic appearance of the GIST in our patient was in keeping with these characteristic findings, including small size, lack of mitotic activity, and spindled morphology. In contrast to sporadic cases, GIST in NF1 is only positive for KIT or PDGRA mutations in less than 10% of cases.16, 44, 45 In NF1 patients, few die from manifestations of GIST. Those with poor outcomes had overtly malignant histologic features, including brisk mitotic activity (>5/50 HPF) or large tumor size (<5 cm).16 In a large case series of 45 NF1 patients with GIST, only three patients died from metastatic disease.16

4. Conclusion

In summary, we present a highly unusual case of an NF1 patient with coincident well-differentiated liposarcoma, GIST and carcinoid tumors. Liposarcoma in NF1 is a rare but described entity. However, a large number of reported cases likely represent liposarcomatous differentiation within peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Carey J.C., Baty B.J., Johnson J.P., Morrison T., Skolnick M., Kivlin J. The genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 1986;486:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb48061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferner R.E. The neurofibromatoses. Pract Neurol. 2010;10(suppl 2):82–93. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.206532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker L., Thompson D., Easton D. A prospective study of neurofibromatosis type 1 cancer incidence in the UK. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(suppl 2):233–238. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laycock-van Spyk S., Thomas N., Cooper D.N., Upadhyaya M. Neurofibromatosis type 1-associated tumours: their somatic mutational spectrum and pathogenesis. Hum Genomics. 2011;5(suppl 6):623–690. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-5-6-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Easton D.F., Ponder M.A., Huson S.M., Ponder B.A. An analysis of variation in expression of neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 (NF1): evidence for modifying genes. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53(suppl 2):305–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabbagh A., Pasmant E., Laurendeau I. Unravelling the genetic basis of variable clinical expression in neurofibromatosis 1. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(suppl 15):2768–2778. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szudek J., Joe H., Friedman J.M. Analysis of intrafamilial phenotypic variation in neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) Genet Epidemiol. 2002;23(suppl 2):150–164. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss S.W., J.R G. 4th ed. Mosby; St. Louis: 2001. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schofer M.D., Abu-Safieh M.Y., Paletta J., Fuchs-Winkelmann S., El-Zayat B.F. Liposarcoma of the forearm in a man with type 1 neurofibromatosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7071. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreyfuss U., Ben-Arieh J.Y., Hirshowitz B. Liposarcoma–a rare complication in neurofibromatosis. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61(suppl 2):287–290. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197802000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker N.D., Tchang F.K., Greenspan A. Liposarcoma complicating neurofibromatosis. Report of two cases. Bull Hosp Jt Dis Orthop Inst. 1982;42(suppl 2):172–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark D.H., Mathews W.R. Simultaneous occurrence of von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis and osteitis fibrosa cystica; report of a case showing both diseases in addition to liposarcoma. Surgery. 1953;33(suppl 3):434–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai A., Onogi K., Sugiyama Y. Omental liposarcoma; a rare complication in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26(suppl 4):381–382. doi: 10.1080/01443610600636152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez C.K., Rosen G., Mitnick R., Chaudhri A. Recurrent retroperitoneal liposarcoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. BMJ Case Rep. 2012:2012. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Agostino A.N., Soule E.H., Miller R.H. Sarcomas of the peripheral nerves and somatic soft tissues associated with multiple neurofibromatosis (Von Recklinghausen's disease) Cancer. 1963;16:1015–1027. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196308)16:8<1015::aid-cncr2820160808>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miettinen M., Fetsch J.F., Sobin L.H., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(suppl 1):90–96. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000176433.81079.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaremko J.L., MacMahon P.J., Torriani M. Whole-body MRI in neurofibromatosis: incidental findings and prevalence of scoliosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;41(suppl 8):917–923. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azumi N., Curtis J., Kempson R.L., Hendrickson M.R. Atypical and malignant neoplasms showing lipomatous differentiation. A study of 111 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11(suppl 3):161–183. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198703000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fletcher C.D. Churchill Livingstone; London: 2000. Soft Tissue Tumors, in Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enzinger F.M., Winslow D.J. Liposarcoma. A study of 103 cases. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med. 1962;335:367–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gritli S., Khamassi K., Lachkhem A. Head and neck liposarcomas: a 32 years experience. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37(suppl 3):347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzpatrick M.O., Tan K., Doyle D. Metastatic liposarcoma of the brain: case report and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13(suppl 4):411–412. doi: 10.1080/02688699943556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghadimi M.P., Al-Zaid T., Madewell J. Diagnosis, management, and outcome of patients with dedifferentiated liposarcoma systemic metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(suppl 13):3762–3770. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariel I.M. Incidence of metastases to lymph nodes from soft-tissue sarcomas. Semin Surg Oncol. 1988;4(suppl 1):27–29. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980040107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang H.Y., Brennan M.F., Singer S., Antonescu C.R. Distant metastasis in retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma is rare and rapidly fatal: a clinicopathological study with emphasis on the low-grade myxofibrosarcoma-like pattern as an early sign of dedifferentiation. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(suppl 7):976–984. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuangshoti S., Benjavongkulchai S., Chittmittrapap S. Malignant mesenchymoma of median nerve: combined nerve sheath sarcoma and liposarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 1984;25(suppl 2):119–123. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930250214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suresh T.N., Harendra Kumar M.L., Prasad C.S., Kalyani R., Borappa K. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with divergent differentiation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(suppl 1):74–76. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tirabosco R., Galloway M., Bradford R., O'Donnell P., Flanagan A.M. Liposarcomatous differentiation in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: a case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206(suppl 2):138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo A., Liu A., Wei L., Song X. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: differentiation patterns and immunohistochemical features - a mini-review and our new findings. J Cancer. 2012;3:303–309. doi: 10.7150/jca.4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodruff J.M., Perino G. Non-germ-cell or teratomatous malignant tumors showing additional rhabdomyoblastic differentiation, with emphasis on the malignant Triton tumor. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1994;11(suppl 1):69–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ducatman B.S., Scheithauer B.W. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors with divergent differentiation. Cancer. 1984;54(suppl 6):1049–1057. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840915)54:6<1049::aid-cncr2820540620>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong S.Y., Teh M., Tan Y.O., Best P.V. Malignant glandular triton tumor. Cancer. 1991;67(suppl 4):1076–1083. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910215)67:4<1076::aid-cncr2820670435>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorensen S.A., Mulvihill J.J., Nielsen A. Long-term follow-up of von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. Survival and malignant neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(suppl 16):1010–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198604173141603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caplin M.E., Buscombe J.R., Hilson A.J., Jones A.L., Watkinson A.F., Burroughs A.K. Carcinoid tumour. Lancet. 1998;352(suppl 9130):799–805. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghassemi K.A., Ou H., Roth B.E. Multiple rectal carcinoids in a patient with neurofibromatosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(suppl 1):216–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatzitheoklitos E., Buchler M.W., Friess H. Carcinoid of the ampulla of Vater. Clinical characteristics and morphologic features. Cancer. 1994;73(suppl 6):1580–1588. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940315)73:6<1580::aid-cncr2820730608>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makhlouf H.R., Burke A.P., Sobin L.H. Carcinoid tumors of the ampulla of Vater: a comparison with duodenal carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1999;85(suppl 6):1241–1249. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990315)85:6<1241::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zoller M.E., Rembeck B., Oden A., Samuelsson M., Angervall L. Malignant and benign tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 in a defined Swedish population. Cancer. 1997;79(suppl 11):2125–2131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuller C.E., Williams G.T. Gastrointestinal manifestations of type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen's disease) Histopathology. 1991;19(suppl 1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilsson B., Bumming P., Meis-Kindblom J.M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era–a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103(suppl 4):821–829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng S.P., Huang M.J., Yang T.L. Neurofibromatosis with gastrointestinal stromal tumors: insights into the association. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(suppl 7–8):1165–1169. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000037806.14471.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh N.M., Bodurtha A. Auerbach's myenteric plexus. A possible site of origin for gastrointestinal stromal tumors in von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114(suppl 5):522–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirota S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: their origin and cause. Int J Clin Oncol. 2001;6(suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/pl00012072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson J., Sihto H., Meis-Kindblom J.M., Joensuu H., Nupponen N., Kindblom L.G. NF1-associated gastrointestinal stromal tumors have unique clinical, phenotypic, and genotypic characteristics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(suppl 9):1170–1176. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000159775.77912.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takazawa Y., Sakurai S., Sakuma Y. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of neurofibromatosis type I (von Recklinghausen's disease) Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(suppl 6):755–763. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000163359.32734.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]