Summary

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is the second most commonly performed bariatric procedure worldwide. Altered circulating gut hormones have been suggested to contribute post-operatively to appetite suppression, decreased caloric intake and weight reduction. In the present study, we report a 22-year-old woman who underwent laparoscopic SG for obesity (BMI 46 kg/m2). Post-operatively, she reported marked appetite reduction, which resulted in excessive weight loss (1-year post-SG: BMI 22 kg/m2, weight loss 52%, >99th centile of 1-year percentage of weight loss from 453 SG patients). Gastrointestinal (GI) imaging, GI physiology/motility studies and endoscopy revealed no anatomical cause for her symptoms, and psychological assessments excluded an eating disorder. Despite nutritional supplements and anti-emetics, her weight loss continued (BMI 19 kg/m2), and she required nasogastric feeding. A random gut hormone assessment revealed high plasma peptide YY (PYY) levels. She underwent a 3 h meal study following an overnight fast to assess her subjective appetite and circulating gut hormone levels. Her fasted nausea scores were high, with low hunger, and these worsened with nutrient ingestion. Compared to ten other post-SG female patients, her fasted circulating PYY and nutrient-stimulated PYY and active glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) levels were markedly elevated. Octreotide treatment was associated with suppressed circulating PYY and GLP1 levels, increased appetite, increased caloric intake and weight gain (BMI 22 kg/m2 after 6 months). The present case highlights the value of measuring gut hormones in patients following bariatric surgery who present with anorexia and excessive weight loss and suggests that octreotide treatment can produce symptomatic relief and weight regain in this setting.

Learning points

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and SG produce marked sustained weight reduction. However, there is a marked individual variability in this reduction, and post-operative weight loss follows a normal distribution with extremes of ‘good’ and ‘poor’ response.

Profound anorexia and excessive weight loss post-SG may be associated with markedly elevated circulating fasted PYY and post-meal PYY and GLP1 levels.

Octreotide treatment can produce symptomatic relief and weight regain for post-SG patients that have an extreme anorectic and weight loss response.

The present case highlights the value of measuring circulating gut hormone levels in patients with post-operative anorexia and extreme weight loss.

Background

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity; it produces marked sustained weight loss, reduced obesity-associated co-morbidities (1) and decreased mortality (2). Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG), the most common procedures that are undertaken globally (3), are known to reduce appetite and decrease caloric intake. The mechanisms that mediate these changes remain to be clarified (4). However, post-operative changes in circulating gut hormones, in particular, the anorectic hormones peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) and the orexigenic hormone ghrelin, have been suggested to play causal roles (5). Weight loss after RYGB and SG follows a normal distribution (6), with ‘good responders’ and ‘poor responders’ exhibiting differential appetite and gut hormone profiles (7) (8).

Case presentation

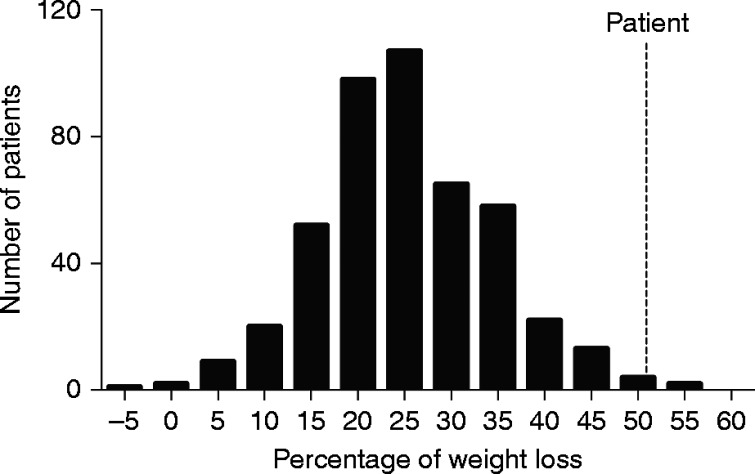

A 22-year-old woman underwent an uneventful laparoscopic SG for severe obesity (weight 135 kg, BMI 46 kg/m2). Her initial post-operative course was unremarkable, except she reported marked loss of appetite. One-year post-SG, she reported continued anorexia, her weight had decreased to 64.6 kg, and her BMI had decreased to 22 kg/m2; this represented a 52% body weight loss, which is at the extreme end of the normal distribution of 1-year post-operative percentage of weight loss for SG patients (n=453) in our bariatric unit (Fig. 1). She did not suffer from flushing or diarrhoea. She was commenced on anti-emetics and received increased dietetic support, including advice on high-energy oral supplements. However, her weight loss continued, and she developed continuous profound nausea with occasional vomiting.

Figure 1.

Histogram of the percentage of weight loss at 1-year post-surgery for all of the sleeve gastrectomies performed by our bariatric unit (n=453). The vertical line at the extreme end of the normal distribution shows the percentage of weight loss of the case that represented a 52% body weight loss.

Investigation

The patient underwent computed tomography (CT) imaging of her abdomen and pelvis, barium swallow and follow-through, oesophageal–gastro-duodenoscopy, oesophageal motility analysis and pH studies, all of which were normal. Psychological assessments excluded an eating disorder. Her symptoms worsened, her weight decreased to 55.8 kg, her BMI decreased to 19.5 kg/m2 and she required in-patient management with nasogastric feeding. A random gut hormone assessment revealed high circulating PYY levels (1200 pg/ml). Her fasted plasma chromogranin A and 5-hydroxy-indoleacetic acid (5HIAA) levels were normal (chromogranin A 51 ng/ml (upper limit of normal 100 ng/ml) and 5HIAA <4 ng/ml (upper limit of normal 13.4 ng/ml)) (9). A 3 h liquid meal study (2 kcal/ml, ResourcePlus Nestle, Nestle Nutrition, Croydon, UK) after an overnight 12 h fast was undertaken to assess her subjective appetite and circulating PYY, GLP1 and ghrelin responses. Because of nausea, she was only able to tolerate 100 ml instead of our standard meal of 250 ml. Blood samples and appetite visual analogue scales (VASs) were taken pre-meal and then at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 min post-meal. In order to preserve the integrity of labile gut hormone, appropriate preservatives/inhibitors were added and blood was processed according to our published protocols (10). She was commenced on octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, 100 μg subcutaneously three times a day, which resulted in an immediate appetite improvement and nausea resolution. The 100 ml meal study was repeated after 14 days of octreotide treatment. Our patient's gut hormone results were compared to those obtained from ten female patients 3 months post-SG (control post-SG group) who underwent a 250 ml liquid meal study. All of the patients gave written informed consent.

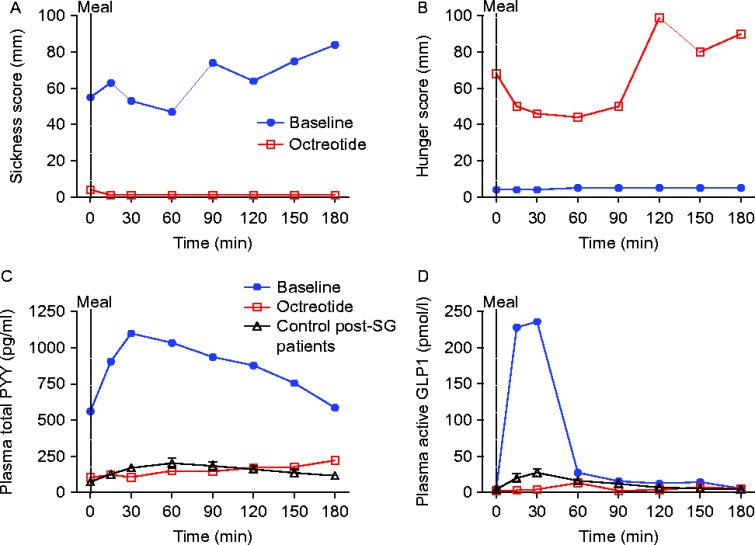

Plasma total PYY, active GLP1, acyl-ghrelin, total ghrelin and insulin were assayed in duplicate by commercially available ELISAs (Millipore, Watford, UK), and plasma glucose was measured by a Yellow Springs Instrument glucose analyser (Yellow Springs, OH, USA). At the start of her baseline study, despite a 12 h fast, she reported high nausea and low hunger. Meal ingestion increased her nausea and further suppressed her hunger (Fig. 2A and B). Her fasted circulating PYY levels were fivefold higher than those of control post-SG patients, and they increased further following nutrient ingestion (Fig. 2C). The PYY area under the curve (AUC) for her baseline meal was 5.5-fold greater than our control post-SG group's PYY AUC, despite our controls consuming two-and-a-half times more calories. Her fasted active GLP1 levels were comparable to those of the control post-SG patients (Fig. 2D). However, her peak active GLP1 was markedly elevated at 15 min post-meal (Fig. 2D). Despite her high nutrient-stimulated GLP1 levels, her nutrient-stimulated plasma insulin levels were not unduly elevated (plasma insulin levels at 15 min post-meal: patient 31.5 pmol/l; control post-SG 23±2.4 pmol/l).

Figure 2.

Graphs of the response to the test meal (200 kcal for case and 500 kcal for control post-SG group) administered at time 0. (A) Subjective sickness score and (B) subjective hunger score (both assessed with the VAS), (C) plasma total PYY levels and (D) active GLP1 levels. Blue line and filled blue circles, case baseline meal; red line and open red squares, case treated with 100 μg octreotide three times a day; black dotted line and open triangles, ten female control post-SG patients.

Both her acyl-ghrelin and total ghrelin levels were undetectable in the fasted and fed states, in contrast to the detectable levels in the control post-SG group. On octreotide treatment, her hunger increased and her nausea resolved (Fig. 2A and B). Her circulating fasted and nutrient-stimulated PYY (Fig. 2C), active GLP1 (Fig. 2D) and insulin levels were suppressed (15 min post-meal 3.2 pmol/l). Her plasma acyl-ghrelin and total ghrelin levels remained undetectable.

Treatment

The patient continued with 100 μg octreotide injected subcutaneously three times a day for 4 months and was then switched to long-acting octreotide, 20 mg sandostatin LAR, administered intramuscularly every 3 weeks. During this time, her nausea and vomiting completely resolved, her appetite increased and her weight increased to 63.4 kg.

Discussion

SG, which involves removing 90% of the gastric fundus while leaving the rest of the gastrointestinal tract intact, has recently been advocated as a ‘stand-alone’ bariatric procedure. However, it has become apparent, at least in the short- to medium-term, that the weight loss and metabolic benefits post-SG are comparable to RYGB (11). Consequently, the number of patients that underwent SG globally per annum increased from ∼25 000 in 2008 to 95 000 in 2011 (3). Furthermore, research efforts have identified that mechanisms other than restriction and/or malabsorption underlie the sustained weight-loss effects and weight-loss-independent glycaemic improvements of these two procedures (5). Decreased energy intake, as a consequence of reduced hunger, altered food preferences and changes in food reward, is a key driver of the sustained weight loss that follows SG and RYGB. Post-operatively, nutrient-stimulated circulating levels of the anorectic gut hormones PYY and GLP1 are markedly increased, whereas plasma levels of the orexigenic hormone ghrelin are reduced post-SG and are lower than those seen after RYGB (12). These post-operative circulating gut hormone changes have been suggested to contribute to the altered feeding behaviour (5). We and others have reported that weight loss following SG and RYGB is variable and follows a normal distribution (6) (13). Interestingly, ‘poor’ and ‘good’ weight loss responders exhibit differential appetite and gut hormone changes post-surgery (7) (8).

We report the first case of a patient post-SG with profound anorexia and excessive weight loss coupled with high fasted PYY levels and elevated nutrient-stimulated GLP1 and PYY levels. Unlike in our control post-SG patients, we were unable to detect either acyl-ghrelin or total ghrelin in our patient at baseline. Previously, we have shown that exogenous PYY administration suppresses circulating ghrelin levels (14) (15), and a similar mechanism may be at work in the present case, with high endogenous PYY levels suppressing ghrelin. Our patient reported disabling nausea with occasional vomiting, symptoms that are entirely consistent with elevated PYY and GLP1 levels (16) (17). Studies that were undertaken in ‘poor’ as compared to ‘good’ weight loss responders have suggested that variability in post-operative gut hormone responses may contribute to variable weight loss outcomes (7) (8). The present case further supports this hypothesis. However, the biological mechanisms that underlie post-operative gut hormone variability remain to be elucidated. High nutrient-stimulated GLP1 levels have been suggested by some but not all researchers to contribute to post-RYGB hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia (18), a complication that affects ∼0.1% of patients post-RYGB (19). Octreotide administration produces symptomatic relief in some of these patients (20), and in others RYGB reversal has been beneficial (21). However, surgical reversal is not possible following SG. Interestingly, there have been reports of resolution of post-RYGB hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia that have allowed medical therapy to be discontinued (21). Possible future outcomes for our patient are that her gut hormone profile could ‘normalise’, which would allow the withdrawal of octreotide therapy or that an increased understanding of enteroendocrine cell biology may enable the selective targeting of her GLP1- and PYY-producing enteroendocrine L-cells. There are some limitations to the present study. We compared the case patient's nutrient-stimulated gut hormone levels to those measured in a relatively small number of control patients who were 3 months post-SG. Thus, the case patient had a lower BMI and greater weight loss as compared to the control post-SG group. These differences in weight loss and interval post-SG could have impacted the circulating gut hormone levels (22). In addition, the case patient could only tolerate 100 ml (200 kcal) of the liquid test meal as compared to the 250 ml (500 kcal) consumed by the control post-SG group, which makes a direct comparison difficult. However, given that nutrient-stimulated plasma GLP1 and PYY levels are proportionate to the calorie load consumed, it is likely that the matching of the caloric loads would have further increased the difference between the case patient and the control group.

Conclusion

The present case highlights the value of measuring gut hormones in patients following SG who present with anorexia and excessive weight loss and suggests that octreotide treatment can produce symptomatic relief and weight regain for patients in this challenging clinical setting.

Patient consent

Full informed consent was obtained from the patient before drafting the case report.

Author contribution statement

A Pucci, W H Cheung, S Manning, H Kingett, M Adamo, M Elkalaawy, A Jenkinson, N Finer, J Doyle, M Hashemi and R L Batterham were directly involved in the management of the patients. A Pucci, W H Cheung and S Manning undertook the meal studies. J Jones and R L Batterham undertook and analysed the hormone assays. A Pucci and R L Batterham drafted the case report. All of the authors contributed to and approved and the final draft of the report.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the Rosetrees Trust (grant number M262-CD1).

References

- 1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Aminian A, Pothier CE, Kim ES, Nissen SE et al. 2015. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes – 3-year outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine 370 2014. 2002–2013. 10.1056/NEJMoa1401329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, Lystig T, Sullivan M, Bouchard C, Carlsson B et al. 2007. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. New England Journal of Medicine 357 741–752. 10.1056/NEJMoa066254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buchwald H & Oien DM. 2013. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obesity Surgery 23 427–436. 10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scott WR & Batterham RL. 2011. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: understanding weight loss and improvements in type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 301 R15–R27. 10.1152/ajpregu.00038.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Madsbad S, Dirksen C & Holst JJ. 2014. Mechanisms of changes in glucose metabolism and bodyweight after bariatric surgery. Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2 152–164. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70218-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manning S, Pucci A, Carter NC, Elkalaawy M, Querci G, Magno S, Tamberi A, Finer N, Fiennes AG, Hashemi M et al. 2014. Early postoperative weight loss predicts maximal weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surgical Endoscopy 29 1484–1491. 10.1007/s00464-014-3829-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. le Roux CW, Welbourn R, Werling M, Osborne A, Kokkinos A, Laurenius A, Lönroth H, Fändriks L, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR et al. 2007. Gut hormones as mediators of appetite and weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Annals of Surgery 246 780–785. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dirksen C, Jorgensen NB, Bojsen-Moller KN, Kielgast U, Jacobsen SH, Clausen TR, Worm D, Hartmann B, Rehfeld JF, Damgaard M et al. 2013. Gut hormones, early dumping and resting energy expenditure in patients with good and poor weight loss response after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. International Journal of Obesity 37 1452–1459. 10.1038/ijo.2013.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carling RS, Degg TJ, Allen KR, Bax ND & Barth JH. 2002. Evaluation of whole blood serotonin and plasma and urine 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid in diagnosis of carcinoid disease. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry 39 577–582. 10.1177/000456320203900605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chandarana K, Drew ME, Emmanuel J, Karra E, Gelegen C, Chan P, Cron NJ & Batterham RL. 2009. Subject standardization, acclimatization, and sample processing affect gut hormone levels and appetite in humans. Gastroenterology 136 2115–2126. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee WJ, Pok EH, Almulaifi A, Tsou JJ, Ser KH & Lee YC. 2014. Medium-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a matched comparison with gastric bypass. Obesity Surgery In press 10.1007/s11695-015-1582-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yousseif A, Emmanuel J, Karra E, Millet Q, Elkalaawy M, Jenkinson AD, Hashemi M, Adamo M, Finer N, Fiennes AG et al. Differential effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic gastric bypass on appetite, circulating acyl-ghrelin, peptide YY3–36 and active GLP-1 levels in non-diabetic humans. Obesity Surgery 24 241–252. 10.1007/s11695-013-1066-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hatoum IJ, Greenawalt DM, Cotsapas C, Reitman ML, Daly MJ & Kaplan LM. 2011. Heritability of the weight loss response to gastric bypass surgery. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 96 E1630–E1633. 10.1210/jc.2011-1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Batterham RL, Cohen MA, Ellis SM, Le Roux CW, Withers DJ, Frost GS, Ghatei MA & Bloom SR. 2003. Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY3–36. New England Journal of Medicine 349 941–948. 10.1056/NEJMoa030204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Batterham RL, ffytche DH, Rosenthal JM, Zelaya FO, Barker GJ, Withers DJ & Williams SC. 2007. PYY modulation of cortical and hypothalamic brain areas predicts feeding behaviour in humans. Nature 450 106–109. 10.1038/nature06212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Derosa G & Maffioli P. 2012. GLP-1 agonists exenatide and liraglutide: a review about their safety and efficacy. Current Clinical Pharmacology 7 214–228. 10.2174/157488412800958686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. le Roux CW, Borg CM, Murphy KG, Vincent RP, Ghatei MA & Bloom SR. 2008. Supraphysiological doses of intravenous PYY3–36 cause nausea, but no additional reduction in food intake. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry 45 93–95. 10.1258/acb.2007.007068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McLaughlin T, Peck M, Holst J & Deacon C. 2010. Reversible hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after gastric bypass: a consequence of altered nutrient delivery. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 95 1851–1855. 10.1210/jc.2009-1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sarwar H, Chapman WH III, Pender JR, Ivanescu A, Drake AJ III, Pories WJ & Dar MS. 2014. Hypoglycemia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: the BOLD experience. Obesity Surgery 24 1120–1124. 10.1007/s11695-014-1260-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Myint KS, Greenfield JR, Farooqi IS, Henning E, Holst JJ & Finer N. 2012. Prolonged successful therapy for hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia after gastric bypass: the pathophysiological role of GLP1 and its response to a somatostatin analogue. European Journal of Endocrinology 166 951–955. 10.1530/EJE-11-1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mordes JP & Alonso LC. 2015. Evaluation, medical therapy, and course of adult persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a case series. Endocrine Practice 21 237–246. 10.4158/EP14118.OR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gerner T, Johansen OE, Olufsen M, Torjesen PA & Tveit A. 2014. The post-prandial pattern of gut hormones is related to magnitude of weight-loss following gastric bypass surgery: a case–control study. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 74 213–218. 10.3109/00365513.2013.877594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a