Abstract

AIM: To assess the efficacy of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy after non-bismuth quadruple therapy failure for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication.

METHODS: Between January 2010 and December 2012, we screened individuals who were prescribed non-bismuth quadruple therapy for H. pylori eradication. Among them, a total of 98 patients who failed non-bismuth quadruple therapy received 1-wk or 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy (400 mg moxifloxacin once daily, and 20 mg of rabeprazole and 1 g of amoxicillin twice daily). H. pylori status was evaluated using the 13C-urea breath test 4 wk later, after treatment completion. The eradication rates were determined by intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses.

RESULTS: In total, 60 and 38 patients received 1-wk and 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy, respectively. The intention-to-treat and per-protocol eradication rates were 56.7% (95%CI: 45.0-70.0) and 59.6% (95%CI: 46.6-71.7) in the 1-wk group and 76.3% (95%CI: 63.2-89.5) and 80.6% (95%CI: 66.7-91.9) in the 2-wk group (P = 0.048 and 0.036, respectively). All groups had good compliance (95% vs 94.9%). Neither group showed serious adverse events, and the proportions of patients experiencing mild side effects were not significantly different (21.1% vs 13.9%). Clinical factors such as age, sex, alcohol and smoking habits, comorbidities, and presence of gastric or duodenal ulcer did not influence the eradication therapy efficacy. The efficacy of second-line eradication therapy did not differ significantly according to the first-line regimen.

CONCLUSION: Two-week moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy showed better efficacy than a 1-wk regimen after non-bismuth quadruple therapy failure.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Moxifloxacin-based triple, Non-bismuth quadruple, Second-line, Eradication

Core tip: We aimed to compare 1-wk and 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapies after non-bismuth quadruple therapy failure for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, especially in patients from a region known to be associated with a high resistance to antibiotics. The eradication rate of the 2-wk group was significantly higher than that of the 1-wk group (76.3% vs 56.7%, P < 0.05), and the incidence of side effects was similar. Thus, a 2-wk regimen may be a reasonable choice as second-line therapy for the eradication of H. pylori infection after non-bismuth quadruple therapy failure.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is well known as the main cause of gastritis, gastroduodenal ulcers, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer[1]. Effective treatment of H. pylori infection remains a challenge, 100% eradication has not been achieved by any current strategy. The recommended first-line regimen for the eradication of H. pylori is the so-called standard triple therapy consisting of a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) and two antibiotics (clarithromycin plus amoxicillin or metronidazole) for at least 7 d[2-6]. However, the efficacy of the standard triple regimen has considerably decreased in patients of most countries[7].

One recent strategy, which could increase eradication rates, is sequential therapy using non-bismuth quadruple drugs. This regimen comprises sequential administration of a dual therapy (amoxicillin with a PPI), followed by a triple therapy (clarithromycin and metronidazole with a PPI)[8]. According to several previous studies, including ours, this sequential eradication treatment regimen shows better efficacy than the standard triple therapy[9-14]. Although the reasons for this improved efficacy are not well understood, the disruption of cell walls caused by amoxicillin during the first phase and the breakage of drug efflux channels responsible for drug resistance may improve the efficacy of clarithromycin during the second phase of treatment[10,15].

Despite the apparent superiority of sequential therapy, one concern is the possibility of poor compliance owing to the complexity of the regimen with a mid-course change of drugs[16]. Accordingly, concurrent prescriptions using the same combination of drugs as sequential therapy (concomitant therapy) have been presented as a good alternative. A recent meta-analysis confirmed that the concomitant regimen was more effective in eradicating H. pylori than the standard triple regimen[17]; our previous clinical trial with sequential and concomitant therapies also showed similar efficacy, compliance, and side effect profiles[18].

The Korean population is reported to be at high risk for H. pylori infection, and South Korea is reported to have a high prevalence of resistance to antibiotics used for the eradication of H. pylori[19,20]. The Maastricht IV report recommends sequential treatment or a non-bismuth quadruple therapy regimen as first-line treatment in areas with high clarithromycin resistance and low availability of bismuth quadruple therapy[2]; thus, non-bismuth quadruple sequential and concomitant therapies are used as first-line eradication regimens for H. pylori infection in South Korea.

Despite these first-line regimens, a considerable number of patients fail to achieve eradication and require second-line treatment. Very few studies have reported on second-line regimens after sequential therapy failure, and none have reported on second-line regimens after concomitant therapy failure. In a pilot study by Zullo et al[21], a 10-d triple regimen with PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin administered after sequential therapy failure had an 86% eradication rate. The current study assessed the efficacy of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment for H. pylori infection after non-bismuth quadruple sequential and concomitant therapy failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Between January 2010 and December 2012, we screened individuals who were prescribed non-bismuth quadruple therapy for H. pylori eradication at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. After identifying cases that had received first-line therapy for the eradication of H. pylori proven by a positive rapid urease test (CLO test; Delta West, Bentley, Australia) or histological evidence with modified Giemsa staining, we identified subjects who required second-line eradication therapy. Within this period, all patients who did not achieve eradication with first-line therapy, except for those lost to follow-up and who refused further treatment, were prescribed moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as a second-line eradication strategy.

The exclusion criteria included the use of H2 receptor antagonists, PPIs, or antibiotics in the previous 4 wk as well as the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within 2 wk before the performance of the 13C-urea breath test, previous gastric surgery, advanced gastric cancer, systemic illness such as liver cirrhosis or chronic renal failure, pregnancy, age < 18 years, and insufficient data.

Study design

As a first-line H. pylori eradication regimen, all subjects received a non-bismuth quadruple regimen comprising 10-d sequential therapy (20 mg of rabeprazole and 1 g of amoxicillin twice daily for the first 5 d, followed by 20 mg of rabeprazole, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 500 mg of metronidazole twice daily for the remaining 5 d), 2-wk sequential therapy (20 mg of rabeprazole and 1 g of amoxicillin twice daily for the first week, followed by 20 mg of rabeprazole, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 500 mg of metronidazole twice daily for the remaining week), or 2-wk concomitant therapy (20 mg of rabeprazole, 1 g of amoxicillin, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 500 mg of metronidazole, twice daily for 2 wk). H. pylori eradication was evaluated at least 4 wk after treatment completion using a 13C-urea breath test.

Participants who did not achieve eradication with the first regimen and who agreed to a second eradication regimen subsequently received a moxifloxacin-containing triple regimen (400 mg of moxifloxacin once daily and 20 mg of rabeprazole and 1 g of amoxicillin twice daily) for either 1 or 2 wk. H. pylori eradication was evaluated as described above.

The primary outcome of this study was the H. pylori eradication rate with the second-line treatment consisting of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy. Treatment compliance and side effects were also assessed.

13C-urea breath test

An initial breath sample was obtained after a 4-h fast. One hundred milligrams of 13C-urea powder (UBiTkit; Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) dissolved in 100 mL water was administered orally. The second breath sample was obtained 20 min later. The cutoff value was 2.6‰. Samples were analyzed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (UBiT-IR300; Otsuka Pharmaceutical).

Statistical analysis

Eradication rates were evaluated by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. The ITT analysis included all assigned patients, and patients with unknown infection status were considered to have eradication failure for the purpose of ITT analysis. The PP analysis excluded patients with unknown H. pylori status following therapy, those who took less than 90% of the treatment doses, and those lost to follow-up or with missing data.

Statistical analysis of the outcomes was performed using the Student’s t-test and χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. Independent factors influencing treatment efficacy were evaluated by univariate analysis using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The analysis was conducted using PASW Statistics for Windows version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

Study group characteristics

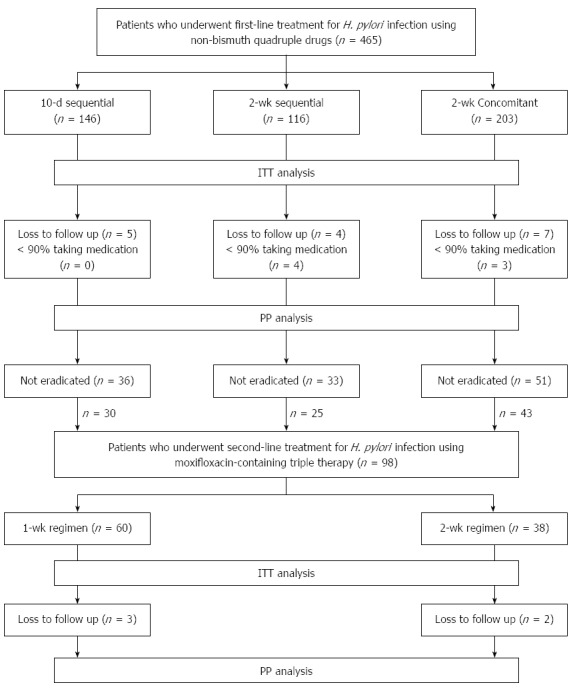

A flow chart of patients who received first-line and second-line treatments for H. pylori eradication during the study period is shown in Figure 1. A total of 465 patients underwent first-line eradication treatment with non-bismuth quadruple therapy: 146, 116, and 203 patients received 10-d sequential therapy, 2-wk sequential therapy, and 2-wk concomitant therapy, respectively. Among these patients, 36, 33, and 51 patients from each treatment group, respectively, showed first-line eradication treatment failure.

Figure 1.

Profile of the first-line and second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. ITT: Intention-to-treat; PP: Per-protocol; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

After excluding patients who refused second-line eradication, 98 patients (30, 25, and 43 patients from each first-line group, respectively) underwent second-line eradication treatment with moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy. The patients who received second-line eradication treatment were divided into two treatment groups: 60 patients (29, 0, and 31 patients from the first-line groups, respectively) received the 1-wk regimen and 38 patients (1, 25, and 12 patients from the first-line groups, respectively) received the 2-wk regimen. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients who received second-line eradication therapy did not differ significantly between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population n (%)

| 1-wk MCT | 2-wk MCT | |

| No. of patients | 60 | 38 |

| Age (mean ± SD), yr | 55.5 ± 9.9 | 59.4 ± 11.7 |

| Sex (male/female), n | 28/32 | 23/15 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Hypertension | 10 (16.7) | 11 (28.9) |

| Diabetes | 2 (3.3) | 5 (13.2) |

| Current smoking | 4 (6.7) | 4 (10.5) |

| Alcohol intake | 10 (16.7) | 7 (18.4) |

| Endoscopic diagnosis | ||

| HPAG | 51 (85.0) | 29 (76.3) |

| GU | 1 (1.7) | 2 (5.3) |

| DU | 7 (11.7) | 5 (13.2) |

| GU + DU | 1 (1.7) | 2 (5.3) |

MCT: Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy; HPAG: Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis; GU: Gastric ulcer; DU: Duodenal ulcer.

First- and second-line treatment outcomes

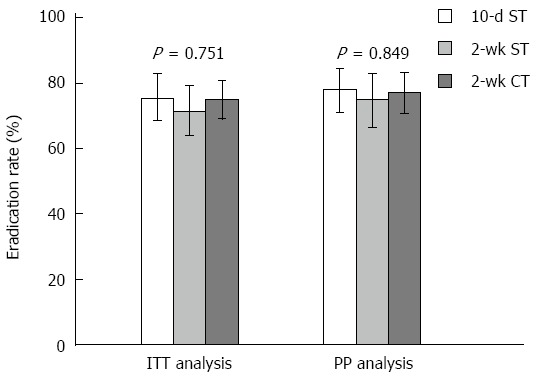

The eradication rates for the first- and second-line treatments are shown in Figures 2 and 3. In the first-line treatment, the eradication rates by ITT analysis were 75.3% (95%CI: 68.5-82.2) in the 10-d sequential group, 71.6% (95%CI: 62.1-79.3) in the 2-wk sequential group, and 74.9% (95%CI: 68.5-80.3) in the 2-wk concomitant group. The eradication rates by PP analysis were 78.0% (95%CI: 71.3-84.8), 75.0% (95%CI: 66.7-82.8), and 77.2% (95%CI: 71.3-83.2), respectively. There was no significant difference in eradication rates between groups. All groups had good compliance (96.6%, 93.1%, and 95.0%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of first-line treatment using non-bismuth quadruple sequential and concomitant therapies. Error bars indicate 95%CI. 10-d ST: Ten-day sequential therapy; 2-wk ST: Two-weeks sequential therapy; 2-wk CT: Two-weeks concomitant therapy; ITT: Intention-to-treat; PP: Per-protocol.

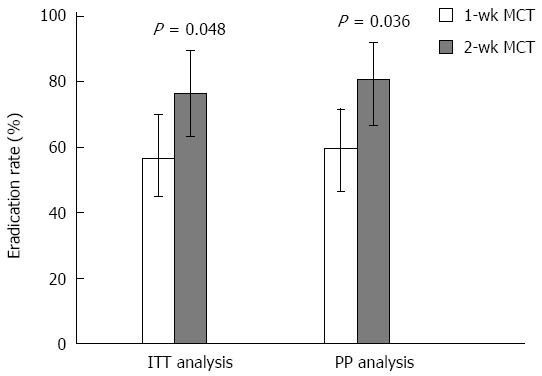

Figure 3.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of second-line treatment using 1-wk and 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy. Error bars indicate 95%CI. 1-wk MCT: One-week moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy; 2-wk MCT: Two-weeks moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy; ITT: Intention-to-treat; PP: Per-protocol.

The outcomes of 1-wk and 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapies for second-line eradication are shown in Table 2. The eradication rates by ITT analysis were 56.7% (95%CI: 75.0-70.0) in the 1-wk group and 76.3% (95%CI: 63.2-89.5) in the 2-wk group; PP analysis showed eradication rates of 59.6% (95%CI: 46.6-71.7) and 80.6% (95%CI: 66.7-91.9), respectively. The eradication rates were significantly higher in the 2-wk group than in the 1-wk group in both the ITT and PP populations (P = 0.048 and P = 0.036, respectively). Five patients were lost to follow-up (three in the 1-wk group and two in the 2-wk group), and both groups had good compliance (95.0% vs 94.9%). Neither group showed serious adverse events that could influence medication adherence, and the proportions of patients experiencing mild side effects were similar in both groups (21.1% vs 13.9%) The reported side effects included nausea, dyspepsia, epigastric soreness, and diarrhea.

Table 2.

Outcomes of 1-wk and 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy n (%)

| 1-wk MCT | 2-wk MCT | P value | |

| Eradication rate | |||

| Intention-to-treat | 34 (56.7) | 29 (76.3) | 0.048 |

| Per-protocol | 34 (59.6) | 29 (80.6) | 0.036 |

| Compliance | 57 (95.0) | 36 (94.9) | 0.954 |

| Side effects | 12 (21.1) | 5 (13.9) | 0.384 |

| Nausea | 5 (11.6) | 0 | 0.178 |

| Dyspepsia | 4 (7.0) | 1 (2.8) | |

| Epigastric soreness | 2 (3.5) | 1 (2.8) | |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1.8) | 3 (8.3) |

MCT: Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy.

The cumulative eradication rates of the first- and second-line treatments were 87.7% (95%CI: 84.7-90.8) and 93.1% (95%CI: 90.7-95.4) in the ITT and PP analyses, respectively.

Clinical factors influencing second-line eradication of H. pylori

As shown in Table 3, univariate analysis was performed to identify clinical factors that influenced the efficacy of second-line treatment for H. pylori infection. Clinical factors such as age, sex, alcohol and smoking habits, comorbidities, and presence of gastric or duodenal ulcer did not influence the efficacy of eradication therapy. In particular, the efficacy of second-line eradication treatment did not differ significantly according to the first-line regimen, although the eradication rate in the 10-d sequential group was slightly lower than in the other groups because of the high proportion of participants who had received the 1-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of the clinical factors influencing the efficacy of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy

| Clinical factor | No. patients | Eradication rate | P value |

| Age, yr | |||

| ≤ 60 | 60 | 61.7% | 0.497 |

| > 60 | 38 | 68.4% | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 47 | 66.0% | 0.740 |

| Male | 51 | 62.7% | |

| Alcohol | |||

| No | 81 | 65.4% | 0.605 |

| Yes | 17 | 58.8% | |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 90 | 64.4% | 1.000 |

| Yes | 8 | 62.5% | |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 77 | 63.6% | 0.797 |

| Yes | 21 | 66.7% | |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 91 | 62.6% | 0.416 |

| Yes | 7 | 85.7% | |

| Gastric ulcer | |||

| No | 92 | 64.1% | 1.000 |

| Yes | 6 | 66.7% | |

| Duodenal ulcer | |||

| No | 83 | 63.9% | 0.834 |

| Yes | 15 | 66.7% | |

| First regimen | |||

| 10-d ST | 30 | 50.0% | 0.138 |

| 2-wk ST | 25 | 68.0% | |

| 2-wk CT | 43 | 72.1% | |

| Second regimen | |||

| 1-wk MCT | 60 | 56.7% | 0.048 |

| 2-wk MCT | 38 | 76.3% |

ST: Sequential therapy; CT: Concomitant therapy; MCT: Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy.

DISCUSSION

The overall eradication rates with 1-wk and 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapies after non-bismuth quadruple therapy failure by ITT analysis were 56.7% (95%CI: 45.0-70.0) and 76.3% (95%CI: 63.2-89.5), respectively. Although neither regimen achieved acceptable eradication levels, the 2-wk regimen was associated with a significantly higher eradication rate than the 1-wk regimen.

Previous studies have reported that longer quinolone-containing triple therapy treatment periods tend to be associated with higher eradication rates. A meta-analysis by Gisbert and Morena[22] found that a 7-d therapy regimen was suboptimal in terms of quinolone-based triple therapy treatment duration. A prospective study performed in Italy showed that patients receiving 10-d levofloxacin-based triple therapy had a higher eradication rate than those receiving 7-d therapy (87.5% vs 67.5%, P = 0.004)[23]. In addition, Chuah et al[24] reported excellent efficacy with 2-wk levofloxacin-containing triple therapy, with an eradication rate of over 90%.

We have reported several retrospective and prospective studies using non-bismuth quadruple sequential and concomitant therapies[13,14,18]. For patients with first-line eradication treatment failure, we previously prescribed 1-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy. However, the efficacy of this regimen was quite disappointing, with an eradication rate of less than 60%. More recently, 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy was administered to patients in an attempt to achieve higher eradication rates than those with the 1-wk regimen. In a retrospective study by Yoon et al[25], an extended duration of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy after standard triple therapy failure did not result in improved efficacy, likely because moxifloxacin resistance has gradually increased. Similarly, 2-wk sequential therapy did not show better outcomes than 10-d sequential therapy, as our previous results have shown. In this study, however, a 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy showed superior efficacy despite being prescribed later.

Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy showed somewhat lower eradication rates in this study despite the significantly higher efficacy of the 2-wk regimen. A pilot study performed in Taiwan reported excellent efficacy with 2-wk levofloxacin-containing triple therapy[24]. In addition, eradication rates with 1-wk and 2-wk moxifloxacin-containing triple therapies were 95.0% and 78.9%, respectively, by ITT analysis in a randomized trial by Miehlke et al[26] in Germany. The high prevalence of moxifloxacin resistance in our region may explain the lower efficacy observed in our study. Although we did not perform antibiotic susceptibility testing, a recent study of 162 patients from our center (2009-2012) showed that 34.6% of H. pylori isolates were resistant to moxifloxacin[20]. This rate was substantially higher than the 18.7% reported by the Taiwanese study described above. The authors reported eradication rates of 92% and 33% for levofloxacin-susceptible and levofloxacin-resistant strains, respectively, by PP analysis. Similarly, in the study by Liao et al[27], treatment success was remarkably influenced by fluoroquinolone susceptibility. With the levofloxacin-containing triple therapy, the success rate was 97.3% in the susceptible group and 37.5% in the resistant group. A study conducted in our hospital showed borderline significance for the effect of moxifloxacin resistance on eradication failure (P = 0.056)[28].

Resistance to antibiotics appears to be the most important contributory factor to treatment failure, although CYP2C19 polymorphism could influence the eradication rate of PPI-based therapy for H. pylori eradication. The frequency of the CYP2C19 polymorphism varies among different ethnic populations. The poor metabolizer genotype is relatively more common in Asians than in Caucasians and African Americans. Although we did not evaluate the CYP2C19 genotype in our study population, a recent study of 2202 patients from our center (2003-2013) evaluated the effect of CYP2C19 genotype on eradication rates[29]. The proportions of extensive metabolizer and poor metabolizer genotypes were 86.0% and 14.0%, respectively. The poor metabolizer genotype was associated with a high eradication rate compared with the extensive metabolizer genotype (86.8% vs 78.2%, P = 0.035). However, the rabeprazole-based regimen used in our study is known to be less affected by the CYP2C19 polymorphism[30].

Another possible explanation is that the increased number of antibiotics during first-line treatment can influence the efficacy of subsequent treatments. More research on this potential factor is required.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study conducted at a single center. The interview regarding side effects after treatment was not well organized and was thus insufficient. For this reason, the prevalence of side effects after the 2-wk therapy was lower than after the 1-wk regimen, although the difference was not statistically significant. In addition, the study population was too small for the study to have sufficient statistical power. Finally, because we did not perform antibiotic susceptibility testing for moxifloxacin, the actual role of antibiotic resistance in eradication could not be assessed.

In conclusion, moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy, especially a 2-wk regimen, showed suboptimal efficacy but demonstrated encouraging results as second-line treatment for H. pylori infection after non-bismuth quadruple sequential and concomitant therapy failure, particularly in light of the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance in South Korea. However, additional prospective studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to confirm these findings.

COMMENTS

Background

Non-bismuth quadruple sequential and concomitant therapies were introduced recently to increase eradication rates. Nevertheless, many patients fail to achieve eradication and require second-line treatment.

Research frontiers

Moxifloxacin has been suggested as an effective antibiotic for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication in a few animal and human studies.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is a preliminary study to assess the efficacy of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy after non-bismuth quadruple therapy failure. The 14-d regimen showed better efficacy than the 7-d regimen and may be a reasonable option for H. pylori eradication.

Applications

This retrospective study provided preliminary results on moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy. Prospective studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to confirm our findings.

Terminology

Non-bismuth quadruple therapy is a novel strategy for H. pylori eradication, using a combination therapy consisting of proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole.

Peer-review

This study focused on the assessment of the efficacy of triple therapy with moxifloxacin as second-line treatment for H. pylori infection after non-bismuth sequential and concomitant therapy failure. Patients who failed to achieve eradication of H. pylori infection despite first-line regimens needed second-line treatment. A total 98 patients received 1-wk or 2-wk moxifloxacin-based triple therapy containing 400 mg moxifloxacin per day and 20 mg rabeprazole and 1 g of amoxicillin twice per day. The H. pylori status was assessed by the 13C-urea breath test 4 wk after treatment. This study is well constructed and statistically evaluated.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, No. B-1302/190-102.

Informed consent statement: The institutional review board waived the requirement for informed consent because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no competing interests.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 11, 2015

First decision: June 19, 2015

Article in press: September 2, 2015

P- Reviewer: Chmiela M, Shimatani T S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597–1604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coelho LG, León-Barúa R, Quigley EM. Latin-American Consensus Conference on Helicobacter pylori infection. Latin-American National Gastroenterological Societies affiliated with the Inter-American Association of Gastroenterology (AIGE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2688–2691. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Gomollón F, Monés J. [Eradication treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Recommendations of the II Spanish Consensus Conference] Med Clin (Barc) 2005;125:301–316. doi: 10.1157/13078424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. A report card to grade Helicobacter pylori therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:275–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zullo A, Rinaldi V, Winn S, Meddi P, Lionetti R, Hassan C, Ripani C, Tomaselli G, Attili AF. A new highly effective short-term therapy schedule for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:715–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moayyedi P. Sequential regimens for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Lancet. 2007;370:1010–1012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61455-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353–1357. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069–379; quiz 1080. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon JH, Lee DH, Song BJ, Lee JW, Kim JJ, Park YS, Kim N, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Lee SH, et al. Ten-day sequential therapy as first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: a retrospective study. Helicobacter. 2010;15:148–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh HS, Lee DH, Seo JY, Cho YR, Kim N, Jeoung SH, Kim JW, Hwang JH, Park YS, Lee SH, et al. Ten-day sequential therapy is more effective than proton pump inhibitor-based therapy in Korea: a prospective, randomized study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:504–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami K, Fujioka T, Okimoto T, Sato R, Kodama M, Nasu M. Drug combinations with amoxycillin reduce selection of clarithromycin resistance during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gisbert JP, Calvet X, O’Connor A, Mégraud F, O’Morain CA. Sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a critical review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:313–325. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c8a1a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essa AS, Kramer JR, Graham DY, Treiber G. Meta-analysis: four-drug, three-antibiotic, non-bismuth-containing “concomitant therapy” versus triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2009;14:109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim JH, Lee DH, Choi C, Lee ST, Kim N, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Hwang JH, Park YS, Lee SH, et al. Clinical outcomes of two-week sequential and concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized pilot study. Helicobacter. 2013;18:180–186. doi: 10.1111/hel.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Shin JH, Roe IH, Sohn SG, Lee JH, Kang GH, Lee HK, Jeong BC, Lee SH. Impact of clarithromycin resistance on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in infected adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1600–1603. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1600-1603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, Nam RH, Chang H, Kim JY, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206–214. doi: 10.1111/hel.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Panella C, Morini S, Ierardi E. Second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication after sequential therapy failure: a pilot study. Therapy. 2006;3:251–254. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gisbert JP, Morena F. Systematic review and meta-analysis: levofloxacin-based rescue regimens after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Caro S, Franceschi F, Mariani A, Thompson F, Raimondo D, Masci E, Testoni A, La Rocca E, Gasbarrini A. Second-line levofloxacin-based triple schemes for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chuah SK, Tai WC, Hsu PI, Wu DC, Wu KL, Kuo CM, Chiu YC, Hu ML, Chou YP, Kuo YH, et al. The efficacy of second-line anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy using an extended 14-day levofloxacin/amoxicillin/proton-pump inhibitor treatment--a pilot study. Helicobacter. 2012;17:374–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon H, Kim N, Lee BH, Hwang TJ, Lee DH, Park YS, Nam RH, Jung HC, Song IS. Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection: effect of treatment duration and antibiotic resistance on the eradication rate. Helicobacter. 2009;14:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miehlke S, Krasz S, Schneider-Brachert W, Kuhlisch E, Berning M, Madisch A, Laass MW, Neumeyer M, Jebens C, Zekorn C, et al. Randomized trial on 14 versus 7 days of esomeprazole, moxifloxacin, and amoxicillin for second-line or rescue treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2011;16:420–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao J, Zheng Q, Liang X, Zhang W, Sun Q, Liu W, Xiao S, Graham DY, Lu H. Effect of fluoroquinolone resistance on 14-day levofloxacin triple and triple plus bismuth quadruple therapy. Helicobacter. 2013;18:373–377. doi: 10.1111/hel.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon K, Kim N, Nam RH, Suh JH, Lee S, Kim JM, Lee JY, Kwon YH, Choi YJ, Yoon H, et al. Ultimate eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori after first, second, or third-line therapy in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:490–495. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JY, Kim N, Kim MS, Choi YJ, Lee JW, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC. Factors affecting first-line triple therapy of Helicobacter pylori including CYP2C19 genotype and antibiotic resistance. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1235–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuo CH, Lu CY, Shih HY, Liu CJ, Wu MC, Hu HM, Hsu WH, Yu FJ, Wu DC, Kuo FC. CYP2C19 polymorphism influences Helicobacter pylori eradication. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16029–16036. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]