Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the safety of endoscopic procedures in neutropenic and/or thrombocytopenic cancer patients.

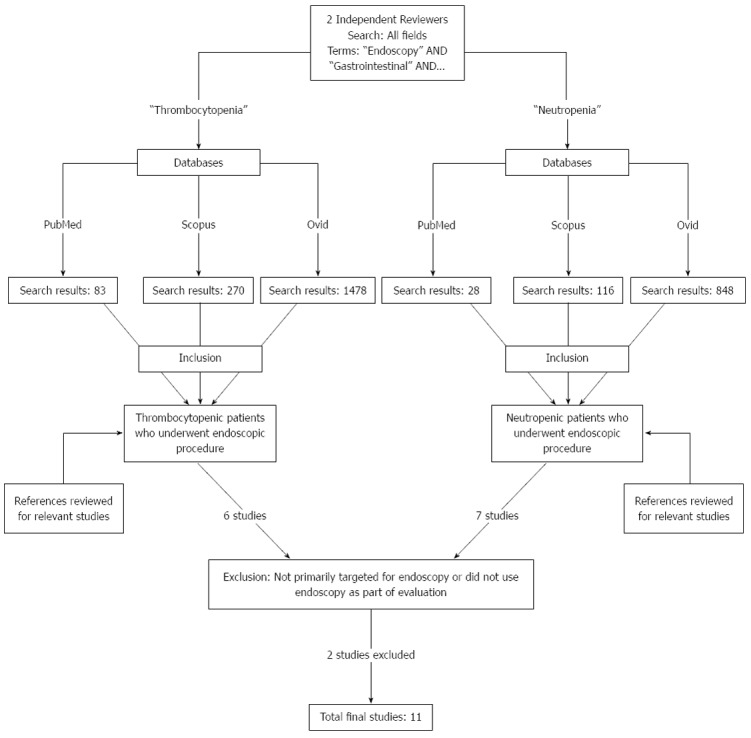

METHODS: We performed a literature search for English language studies in which patients with neutropenia and/or thrombocytopenia underwent endoscopy. Studies were included if endoscopic procedures were used as part of the evaluation of neutropenic and/or thrombocytopenic patients, yielding 13 studies. Two studies in which endoscopy was not a primary evaluation tool were excluded. Eleven relevant studies were identified by two independent reviewers on PubMed, Scopus, and Ovid databases.

RESULTS: Most of the studies had high diagnostic yield with relatively low complication rates. Therapeutic endoscopic interventions were performed in more than half the studies, including high-risk procedures, such as sclerotherapy. Platelet transfusion was given if counts were less than 50000/mm3 in four studies and less than 10000/mm3 in one study. Other thrombocytopenic precautions included withholding of biopsy if platelet count was less than 30000/mm3 in one study and less than 20000/mm3 in another study. Two of the ten studies which examined thrombocytopenic patient populations reported bleeding complications related to endoscopy, none of which caused major morbidity or mortality. All febrile neutropenic patients received prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in the studies reviewed. Regarding afebrile neutropenic patients, prophylactic antibiotics were given if absolute neutrophil count was less than 1000/mm3 in one study, if the patient was undergoing colonoscopy and had a high inflammatory condition without clear definition of significance in another study, and if the patient was in an aplastic phase in a third study. Endoscopy was also withheld in one study for severe pancytopenia.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopy can be safely performed in patients with thrombocytopenia/neutropenia. Prophylactic platelet transfusion and/or antibiotic administration prior to endoscopy may be considered in some cases and should be individualized.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Neutropenia, Cancer, Bone marrow transplant, Bleeding, Hemorrhage, Infection, Fever, Complication, Thrombocytopenia

Core tip: Gastroenterologists are often requested to perform endoscopic evaluation in neutropenic and thrombocytopenic patients. Endoscopists may be hesitant to perform these procedures in these situations, due to the fear of possible complications, such as bleeding and infection. In this systematic review, we provide gastroenterologists with the available safety data, preventive measures prior to the procedures, and the diagnostic yield of the procedures in this patient population.

INTRODUCTION

There are multiple causes for thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, especially in malignant conditions. Both are most commonly seen following chemotherapy for cancer patients or immunosuppression for bone marrow transplant recipients. Additional etiologies include aplastic anemia and hypersplenism. This review will focus on cancer patients with thrombocytopenia as opposed to more acute scenarios, such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). Thrombocytopenia increases the risk of bleeding, in particular from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, while neutropenia carries the risk of infection with high morbidity and mortality.

Gastroenterologists may be consulted during the course of thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia for evaluation of GI symptoms. Symptoms, such as GI bleeding, dysphagia, odynophagia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and alteration of bowel habits, may require evaluation by endoscopy. Clinical suspicion for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) or an underlying fungal infection may also require endoscopic evaluation. In such clinical situations, one may be hesitant to perform endoscopy.

We performed a systematic review of the literature to help assess the safety of performing endoscopic procedures in thrombocytopenic and/or neutropenic patients. Currently there is very limited data available, but our goal is to increase awareness of this important topic and help further develop evidence-based guidelines.

Current guidelines for endoscopy and thrombocytopenia

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) acknowledged that the minimal platelet threshold for endoscopy has not been established[1]. In 2012, based on limited data[2-4], ASGE guidelines concluded that a platelet level of 20000/mm3 or greater can be used as a threshold for performing diagnostic upper endoscopies, but a threshold of 50000/mm3 may be considered before performing biopsies[1]. The ASGE also provided the guidelines shown below, stratifying procedures into high and low risk for bleeding[5]: (1) Low risk procedures: diagnostic [esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy], including biopsy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) without sphincterotomy, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) without fine needle aspiration (FNA), capsule endoscopy, enteroscopy and diagnostic balloon-assisted enteroscopy, and enteral stent deployment without dilation; and (2) High risk procedures: polypectomy, biliary or pancreatic sphincterotomy, pneumatic or bougie dilation, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement, therapeutic balloon-assisted enteroscopy, EUS with FNA, treatment of varices, endoscopic hemostasis, tumor ablation by any technique, and cystogastrostomy.

In a systematic review in 2012, the threshold for platelet transfusion in patients with non-variceal upper GI bleeding was evaluated by analyzing 10 studies, including four randomized controlled trials and six cohort studies[6]. Due to the paucity of high level evidence, the proper threshold of platelet transfusion specifically in GI bleeding was based on expert opinion, and transfusion of platelets to 50000/mm3 was proposed for GI bleeding[6].

The current general recommendation for platelet transfusion is for a goal of 50000/mm3 prior to any intervention[7,8]. British guidelines recommend ensuring the availability of platelet support before endoscopic intervention when the platelet count is below 50000-80000/mm3, with no clear established guideline for prophylactic platelet transfusion in thrombocytopenic patients who undergo endoscopy[9].

Current guidelines for endoscopy and neutropenia

According to the ASGE, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against administration of prophylactic antibiotics prior to routine endoscopic procedures in patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count or ANC < 500 cells/mL) and that the decision to use antibiotics in these scenarios should be individualized[10].

The Infectious Diseases Society of America[11] does not provide any recommendations regarding endoscopy in neutropenic patients. The American Heart Association does not provide guidance regarding prevention of endocarditis in neutropenic patients undergoing endoscopy either[12].

On the other hand, both the British and European guidelines recommend antibiotics prior to endoscopy if the ANC is less than 500/mm3 and the patient is undergoing a high-risk procedure, such as ERCP with obstructed system, endoscopic dilatation, and sclerotherapy[9,13,14].

Studies with relevant information are outdated. The studies evaluating the incidence of bacteremia in patients with bone marrow transplant revealed contradictory results[15,16], with one study reporting clinically relevant bacteremia occurring in 19% of the 47 patients requiring EGD[15], while the other found no episodes of clinically relevant bacteremia after 67 upper and lower endoscopies in 53 patients[16].

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) reviewed the risk of bacteremia associated with specific endoscopic procedures in immunocompetent patients. The procedures were categorized as low risk (< 10% risk) and high risk (≥ 10%). Low risk procedures included EUS with FNA, colonoscopy, diagnostic EGD with or without biopsy, rectal digital exam, rigid proctosigmoidoscopy, ERCP without duct occlusion, and variceal band ligation. High risk procedures included sclerotherapy, ERCP with occluded duct, esophageal laser therapy, and esophageal dilation/prosthesis[14].

Comparisons of United States and British guidelines for endoscopy in neutropenic and thrombocytopenic patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of United States and British guidelines for endoscopy in thrombocytopenic and neutropenic patients

| US guidelines | British guidelines | |

| Thrombocytopenia and endoscopy | ASGE: Acknowledge limited data. Platelet threshold 20000/mm3 for diagnostic endoscopy; 50000/mm3 if biopsies performed | BSG: Ensure platelet support is available before endoscopic intervention when platelet count is < 50000-80000/mm3 |

| Neutropenia and endoscopy | ASGE: Recommend considering antibiotic in immunosuppressed patients undergoing a high-risk procedure | BSG: Recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for ANC < 500/mm3 and undergoing a high risk procedure (based on risk of bacteremia in immunocompetent patients) |

ASGE: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; BSG: British Society of Gastroenterology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To evaluate the safety of the endoscopic procedures in cancer patients with thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia, two independent reviewers performed an extensive search of the English literature in PubMed, Scopus, and Ovid databases from January 1980 to February 2014 using a combination of keywords, such as “endoscopy”, “gastrointestinal”, “neutropenia”, “thrombocytopenia”, “aplastic anemia”, and “cancer”. Potential studies were identified using the inclusion criteria of evaluation of endoscopic procedure in thrombocytopenic and/or neutropenic patient populations. The search was also limited to human studies. After this initial search, selected articles were screened, and those that were not primarily targeted at endoscopy or did not use endoscopy as part of patient evaluation were excluded. Once a study of interest was identified, the full text was retrieved and further evaluated, and the references were searched for any additional relevant studies. A net total of 11 studies were identified that discuss endoscopy as the primary target or as a part of the evaluation for GI symptoms in thrombocytopenic and/or neutropenic patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Method of literature search on PubMed, Scopus, and Ovid databases.

The following data were retrieved: type of endoscopic procedures, adverse events, preventive measures when taken, diagnostic yield, and adverse events related to the endoscopic procedures.

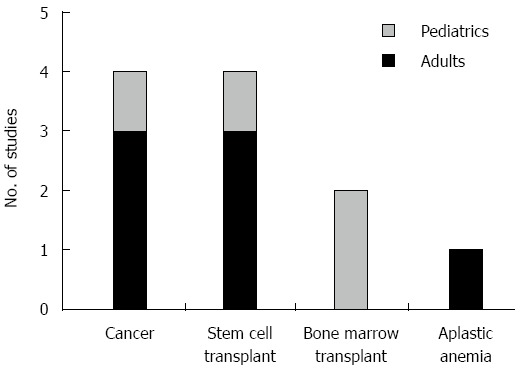

The patient populations differed in the included studies. Four studies were done in stem cell transplant patients, two in bone marrow transplant patients, and one in aplastic anemia patients (Figure 2). Also, four studies were performed in the pediatric population while the other seven were performed in adults.

Figure 2.

Nature of patients studied and etiologies of neutropenia or thrombocytopenia.

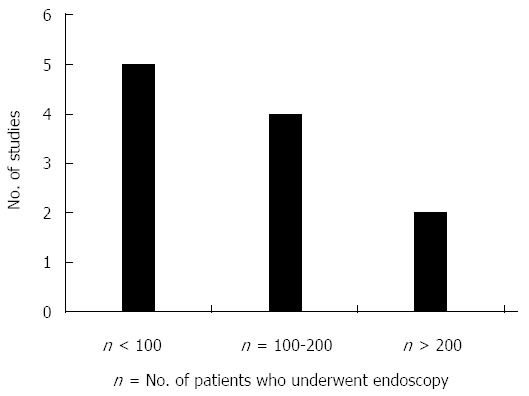

Due to the limited number of relevant studies, both retrospective (8 studies) and prospective (3 studies) studies were included. For the same reason, we did not exclude studies based on study design or number of patients evaluated (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Size of study.

RESULTS

Study design

Please refer to Table 2 for a summary of study design and patient and endoscopic characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Study design and characteristics of patients and endoscopies

| Study | Design | Patient and endoscopic characteristics |

| Buderus et al[19] (2012) | Retrospective 1995-2004 | 38 pediatric cancer patients with various GI complaints |

| 40 diagnostic endoscopies, 7 follow-up endoscopies, 10 therapeutic endoscopies | ||

| Diagnostic yield 82.5%: Gastritis, esophagitis, duodenitis, colitis, Mallory-Weiss tears, ulcer | ||

| Chu et al[17] (1983) | Retrospective 1978-1979 | 133 cancer patients with thrombocytopenia and overt GI bleed |

| 187 diagnostic endoscopies, no therapeutic endoscopies | ||

| Diagnostic yield 92% for upper, 60% for lower exam: Unifocal and multifocal lesions in majority; rare diffuse bleeding | ||

| Gorschlüter et al[20] (2008) | Retrospective 1993-2005 | 104 acute leukemia patients after myelosuppressive chemotherapy |

| 131 primary endoscopies, 40 follow-up endoscopies; includes 16 therapeutic interventions and 5 ERCPs (2 for jaundice, 2 for suspicion of cholecystitis, 1 for suspicion of cholangitis) | ||

| Diagnostic yield 91% for upper, 70% for lower exam: esophagitis, gastric erosions, hiatal hernia, gastritis | ||

| Kaur et al[22] (1996) | Retrospective 1986-1993 | 43 post-bone marrow transplant patients with overt GI bleed |

| 31 endoscopies total: 26 EGD, 5 colonoscopy; 2 endoscopies required hemostasis | ||

| Diagnostic yield 100% for upper, 80% for lower exam: Diffuse esophagitis, gastritis, or duodenitis in upper exam; 2 ulcers, 1 colitis, 1 tumor recurrence in lower exam | ||

| Kaur et al[23] (2013) | Retrospective 2007-2010 | 11 pediatric patient requiring PEG placement in anticipation of BMT (BMT group) compared with 30 patients requiring PEG placement for other indications (comparison group) |

| Khan et al[24] (2006) | Retrospective 1995-2002 | 191 pediatric patients who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| 198 EGDs, 220 lower endoscopies. All diagnostic endoscopies for GI complaints, mostly for nausea, vomiting, and non-bloody diarrhea. | ||

| Diagnostic yield 32% for upper, 16% for lower exam: | ||

| Mucosal abnormalities most common | ||

| Acute GVHD in 14% on histological exam | ||

| Non-GVHD histological evidence of inflammation in 24% | ||

| Park et al[21] (2010) | Retrospective 2002-2007 | 32 patients with aplastic anemia and overt GI bleed, each evaluated by endoscopy, 3 of which required therapeutic intervention |

| Diagnostic yield 66%: bleeding sites in esophagus, stomach, duodenum, small intestine, large intestine | ||

| Ross et al[25] (2008) | Retrospective 2002-2006 | 112 patients with simultaneous upper and lower endoscopic procedures following hematopoietic stem cell transplant. All diagnostic endoscopies for GI symptoms |

| Diagnostic yield: GVHD diagnosed in 81% of patients | ||

| Schulenburg et al[26] (2004) | Prospective cohort 1996-2001 | 42 post-allogeneic stem cell transplant patients admitted for GI complaints |

| 22 upper, 12 lower, and 13 upper and lower endoscopies performed, unclear distinction between primary and follow-up endoscopies | ||

| Diagnostic yield 100%: Majority GVHD, gastritis, CMV, bacterial enteritis | ||

| Schwartz et al[18] (2001) | Prospective cohort 1985-1987 and 1996-1997 | 1102 patients with hematopoietic cell transplantation followed prospectively, of whom 75 developed severe GI bleed. Endoscopic evaluation included diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, however, number of procedures was unclear |

| Diagnostic yield: Majority had multiple sites of bleed, caused by GVHD and peptic acid esophageal ulcers | ||

| Soylu et al[27] (2005) | Prospective cohort 1999-2005 | 451 patients with hematological malignancies, of which 32 developed overt GIB |

| 25 upper GI bleeding episodes, of which 8 EGDs were performed, remainder managed by supportive care. The other 7 patients had lower GI bleed episodes caused by neutropenic enterocolitis excluding the need for endoscopic procedures. | ||

| Diagnostic yield 100% (8 endoscopies): Erosive gastritis (5/8), duodenal ulcers (3/8) in upper GI bleed |

GI: Gastrointestinal; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; PEG: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; GVHD: Graft-vs-host disease.

Of the 11 studies identified, four studies focused on cancer patients, four on post-stem cell transplant patients, two on patients undergoing bone marrow transplant, and one on patients with aplastic anemia (Figure 2). One of the studies on cancer patients focused exclusively on thrombocytopenic patients[17].

Seven of the studies investigated adults, while the other four investigated the pediatric population. Most studies were conducted between 1985 and 2007, with the exception of one that was conducted in the 1970s. Eight studies were retrospective chart reviews, and three were prospective cohort studies. Overt GI bleed was investigated in five studies, while subjects in the remainder of the studies had general GI complaints as the indication for endoscopic procedures. Not all studies looked purely at thrombocytopenic and/or neutropenic patients.

Endoscopic therapeutic interventions

Of the 11 studies, six described therapeutic interventions[18-23] (Table 3). Endoscopic hemostasis was discussed in six studies, which included sclerotherapy for varices, epinephrine and/or fibrin glue injections, electrocautery with or without injection, clip placement, and argon plasma coagulation (APC)[18-22,24]. All were successful with the exception of one study, which had a very small sample size[18].

Table 3.

Thrombocytopenic precautions, therapeutic interventions, and bleeding adverse events

| Study | Thrombocytopenic precautions | Therapeutic intervention | Bleeding Adverse events |

| n = No. thrombocytopenic patients | |||

| Buderus et al[19] | Platelets < 30000/mm3: Biopsies not taken | 4 PEG tube placements | None |

| n = 12 (Platelets < 50000/mm3; 3 of 12 had platelets < 30000/mm3) | 1 PEG tube removal | ||

| 2 sclerotherapies for varices | |||

| 6 NJ tubes placement | |||

| Chu et al[17] | Platelets < 20000/mm3: Biopsies not performed | None | None |

| Platelet transfusion not a prerequisite, but made available | |||

| n = 44 (Platelets < 40000/mm3; 25 of 44 had platelets < 20000/mm3) | |||

| Gorschlüter et al[20] | Platelets < 10000/mm3: Prophylactic platelet transfusion | 8 endoscopic hemostasis in upper exam, including: | 2 of 106 (1.9%) primary upper EGD had proven adverse events: hemorrhage induced by EGD (one stopped bleeding spontaneously and the other one required injection |

| n = unknown | 5 used fibrin glue | ||

| Median platelets 23000/mm3 | 2 used fibrin glue plus epinephrine | ||

| 1 used epinephrine alone | |||

| ERCP in 5 patients | |||

| Duodenal tube placement in 8 patients | No ERCP-related adverse events | ||

| Kaur et al[22] | Platelets < 50000/mm3: | 2 patients underwent successful electrocautery for bleeding ulcers | 10 of the 31 patients in which endoscopies were performed had recurrent bleed at median of 7 d after index bleed (range 2-27 d), none readmitted |

| Prophylactic platelet transfusion | |||

| No target platelet count sought | |||

| For all patients: | |||

| Prophylaxis with H2 blockers or sucralfate or both | No adverse events as a result of endoscopy | ||

| Hematopoietic cell progenitor support | |||

| n = 27 (Platelets < 50000/mm3) | |||

| Kaur et al[23] | None | 11 PEG tube placements | None reported |

| n = unknown | |||

| Khan et al[24] | For platelets < 50000/mm3: Platelets transfused during procedure | None | GI bleeding adverse events occurred in 12 procedures out of 418 total procedures (2.9%). Thrombocytopenia was significantly associated (P < 0.01) with bleeding, occurring in 10 of the 12 procedures with bleeding adverse events |

| n = 111 (Platelets < 50000/mm3) | |||

| 8 cases of bleeding events following EGD, of which there were: | |||

| 4 cases of duodenal hematomas that resolved with conservative management | |||

| 1 case requiring repeat endoscopy with electrocautery | |||

| 3 cases of acute GVHD managed conservatively | |||

| 4 cases of bleeding events following lower endoscopy" | |||

| All due to acute GVHD | |||

| Appear to have been managed conservatively | |||

| Park et al[21] | For platelets < 5000/mm3 or unstable (fever, hemorrhagic signs) patients with a platelet < 10000/mm3: | 3 patients successfully treated with argon plasma coagulation for gastric angiodysplasia, hemoclips on colon ulcer, hemoclips on duodenal Dieulafoy’s lesion | 1 death from massive GI bleed |

| Re-bleed of Dieulafoy lesion, successfully treated by re-clipping | |||

| Prophylactic platelet transfusion | No adverse events attributable to endoscopy | ||

| n = unknown | |||

| Ross et al[25] | For platelets < 25-50000/mm3: | None | None reported |

| Prophylactic platelet transfusion at discretion of endoscopist | |||

| 44 patients received prophylactic platelet transfusion | |||

| n = at least 44 (Platelets < 25000-50000) | |||

| Schulenburg et al[26] | For platelets < 50000/mm3: Prophylactic platelet transfusion | None | None |

| Platelet support to maintain count > 20000/mm3 | |||

| n = unknown | |||

| Schwartz et al[18] | For platelets < 50000/mm3: | 2 attempted endoscopic hemostasis | No adverse events attributable to endoscopy reported |

| No endoscopy if 50000/mm3 not reached | 1 injection successful | ||

| n = unknown | 1 bipolar cautery plus injection that was unsuccessful and required surgery | ||

| Soylu et al[27] | For platelets < 20000/mm3: | None | No deaths or adverse events attributable to endoscopy |

| Prophylactic platelet transfusion | |||

| Active bleeding with higher platelet count also received prophylactic transfusion | |||

| Severe thrombocytopenia (level not defined): | |||

| EGD withheld in 17 of 25 upper GI bleeding episodes | |||

| Colonoscopy withheld in 7 lower GI bleeding episodes | |||

| n = unknown |

GI: Gastrointestinal; EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; PEG: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; GVHD: Graft-vs-host disease.

Two studies described successful placement of duodenal and naso-jejunal feeding tubes[19,20]. One study described five patients who underwent ERCP with and without sphincterotomy, three of which had true pathology in the biliary tree while the remaining two patients had no abnormality detected[20]. Successful PEG tube placements were described in two studies; however, both studies reported infectious adverse events in neutropenic patients (see “Infectious Adverse Events” below)[19,23].

Thrombocytopenic patient populations

Ten of the 11 studies investigated thrombocytopenic patient populations and commented on precautions used. In five studies, transfusions were given if the platelet count was less than 50000/mm3[18,22,24-26]. In patients with an overt GI bleed, different approaches were undertaken, including platelet transfusion if the count was < 10000[21], < 20000[27], or < 50000/mm3[22], avoiding endoscopy if the platelet count of 50000/mm3 was not achieved[18], or making the platelets available as needed without requiring transfusion as a prerequisite indication prior to endoscopic procedures[17].

In the study by Buderus et al[19], prophylactic transfusions were not given but no biopsies were taken if the platelet count was < 30000/mm3. In the study by Gorschlüter et al[20], prophylactic platelets were given if the platelet count was < 10000/mm3.

Three studies discussed thrombocytopenic precautions for biopsies[17,19,24]. These precautions included withholding biopsies if the count was less than 20000/mm3[17], withholding biopsies if the count was less than 30000/mm3[19], or avoiding duodenal biopsies if the risk of bleeding was estimated to be high, although a specific platelet count was not mentioned and four cases of duodenal hematoma (one associated with pancreatitis) were reported in that study[24] (Table 3).

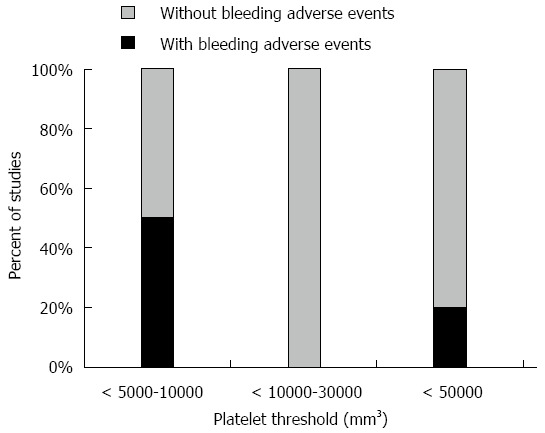

Bleeding adverse events

Out of the four studies with records of bleeding adverse events, two studies reported bleeding adverse events related to endoscopy[20,24]. The total number of bleeding adverse events was very small, ranging from 2/106 to 12/418 (1.9%-2.9%) endoscopic procedures, and most of them were managed conservatively with the exception of three patients who needed repeat endoscopy. One of these three patients stopped bleeding spontaneously[20], another required injection[20], and the last one required electrocautery[24]. Four additional patients developed duodenal hematomas, which were managed conservatively[24]. None of the above adverse events caused major morbidities.

Bleeding adverse events were found to be relatively low among thrombocytopenic patients. Figure 4 summarizes the proportion of studies with and without bleeding adverse events for each given platelet cutoff.

Figure 4.

Proportional distribution of studies with and without bleeding adverse events for platelet threshold level used for taking precautions (i.e., withhold biopsy, transfuse platelets).

Neutropenic patient populations

Neutropenia was generally defined as an absolute neutrophilic count of less than 500 cells/mm3, although two studies defined it as ANC < 1000/mm3[17,22] while another study used a cut off of 1500/mm3[23]. Eight studies involved neutropenic patients undergoing endoscopy[17-23] (Table 4). Broad-spectrum antibiotics were given to all patients with neutropenia and fever. Precautions for afebrile neutropenic patients varied among the studies. One study gave all patients antibiotics during the aplastic phase[26]. In a second study, endoscopy was not performed if pancytopenia was severe, defined as very low values in two or more cell lines, including ANC < 500/mm3, platelet count < 20000/mm3, and absolute reticulocyte count < 60000/mm3[21]. In the study by Khan et al[24], broad-spectrum antibiotics were given if the absolute neutrophilic count was < 1000/mm3. In Buderus’ study, antibiotics were given to the patients undergoing colonoscopy who had high inflammatory conditions without clear definition of this state, and upper endoscopies were performed under aseptic conditions if the absolute neutrophil count was < 1000/mm3; however, these conditions were not defined[19].

Table 4.

Neutropenic precautions and infectious adverse events

| Study | Neutropenic precautions | Infectious adverse events |

| n = No. of afebrile neutropenic patients | ||

| Buderus et al[19] | ANC < 1000/mm3 threshold: | One (2.1%) procedure-related adverse event: |

| Upper endoscopies performed under “aseptic conditions” (not defined), appears that this did not include antibiotic prophylaxis | Fever and abdominal tenderness after colonoscopy | |

| Colonoscopies performed under antibiotic prophylaxis n = 10 (ANC < 1000/mm3) | Patient had not received antibiotic prophylaxis despite neutropenia (ANC 490/mm3); no explanation given in article | |

| Symptoms resolved in 2 d under IV antibiotics | ||

| Chu et al[17] | None | None |

| n = unknown | ||

| Gorschlüter et al[20] | Neutropenia not defined | 16 of 106 (15%) primary upper EGD: Fever within 48 h |

| n = unknown | 3 of 20 (15%) primary colonoscopies: Fever within 48 h | |

| Median WBC 1.5 G/l | Total # patients with fever following endoscopy: 19. | |

| 5 of these died within 10 d. | ||

| Not significantly different from # patients who died without having a fever following endoscopy. | ||

| No ERCP-related adverse events | ||

| Kaur et al[22] | Neutropenia not defined | 2 deaths due to sepsis |

| n = unknown | No adverse events attributed to endoscopy | |

| Kaur et al[23] | No neutropenic precautions taken | 4 (36%) infectious adverse events total (both neutropenic and non-neutropenic) |

| n = 4 (ANC < 1500/mm3) | ||

| 2 patients neutropenic at time of PEG placement. | ||

| First patient had cellulitis and small abscess at PEG site, treated by removal of PEG | ||

| Second patient had cellulitis at PEG site, treated by IV antibiotics | ||

| 2 patients non-neutropenic at time of PEG placement, but had neutropenia at the time of infection | ||

| Khan et al[24] | For ANC < 1000/mm3: | No infectious adverse events related to endoscopy. |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics prophylaxis | 1 colonic perforation resulting in death | |

| n = 148 (WBC < 4000/mm3) | ||

| Park et al[21] | “Severe aplastic anemia” defined as bone marrow cellularity less than 25% and very low values for at least 2 of 3 hematopoietic lineages (including ANC < 500/mm3) | No adverse events attributable to endoscopy |

| No precautions (no patients with fever) | ||

| n = 28 (Severe aplastic anemia) | ||

| Ross et al[25] | None | None reported |

| n = 0 | ||

| Schulenburg et al[26] | Antibiotic prophylaxis during aplasia for all patients | None |

| No extra prophylaxis for endoscopy | ||

| Schwartz et al[18] | None | No adverse events attributable to endoscopy |

| n = unknown | ||

| Soylu et al[27] | Severe neutropenia (level not defined): | No adverse events attributable to endoscopy |

| Withhold endoscopy in 17 upper and 7 lower GI bleed episodes | ||

| n = unknown |

EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; PEG: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; GI: Gastrointestinal.

Infectious adverse events

Infectious adverse events were discussed in three of the seven studies[19,20,23]. One study reported fever and abdominal tenderness in a neutropenic patient who did not receive prophylactic antibiotics prior to colonoscopy[19]. In the second study, 15% of patients undergoing upper and lower endoscopy developed fever within 48 h after the procedure, of whom 26% (five patients) died thereafter[20]. No patients died as a direct result of endoscopy, and the death rate was not significantly different in patients who did or did not have a fever following endoscopy.

ANC at the time of PEG tube placement appeared to have a major influence on outcome, with a high infection rate in neutropenic patients. Infection can also occur when the patient becomes neutropenic after the PEG tube placement[23]. PEG placement should be avoided if possible during significant neutropenic episodes[23].

Benefits of endoscopic procedures

The diagnostic yield varied among the studies, ranging from 30% to 100% among patients who underwent upper endoscopy. The yield for colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy was lower. The majority of the findings were esophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis, erosions, ulcers, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, fungal infection, GVHD, hiatal hernia, colitis, proctitis, and tumors.

Chu et al[17] showed in patients who have thrombocytopenia and GI bleed that unifocal or multifocal source of bleeding was the most common finding rather than diffuse mucosal oozing, which accounted for only 12% of patients with platelet counts < 40000/mm3 in this study.

Although the treatment plan was changed for more than 55% of patients undergoing upper endoscopy, this was mostly comprised of the addition or modification of acid suppression therapy[20].

DISCUSSION

Based on our literature review, it appears that endoscopy can be safely performed in most thrombocytopenic and neutropenic patients. Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia should not be viewed as absolute contraindications for endoscopy. In fact, endoscopy can provide a high diagnostic utility, helping to discern peptic ulcer disease, GVHD, and viral and fungal infections, among other diagnoses. Additionally, we learned that diffuse mucosal oozing is unlikely to be the etiology for a GI bleed in this group of patients[17]. It is also clear that endoscopic interventions, including hemostasis, feeding tube placement, and even ERCP, can be accomplished successfully. One interesting finding is that peptic ulcer disease was a common finding. Hence, one may consider attempting empiric acid suppression therapy before endoscopic evaluation in high risk patients.

Most studies used a threshold of 50000/mm3 for prophylactic platelet transfusion prior to endoscopic procedures, although some performed uneventful endoscopies with lower counts. Therefore, based on this review and general practice guidelines, we recommend using 50000/mm3 as the threshold to perform endoscopy. However, if clinically required, lower platelet counts may be considered by the endoscopist. Platelet transfusion during the procedure for patients who could not maintain this threshold is an option especially if a high risk procedure is planned. Although patients with lower platelet levels have undergone endoscopic procedures or endoscopic biopsies, duodenal biopsies, in particular, should be avoided if the platelet count is < 20000/mm3, as they can be a high risk factor for bleeding and hematoma development.

In terms of the clinical application of platelet threshold, it is worth considering the risk and benefit of platelet transfusion to achieve a platelet goal. Transfusion is not without risks. Alloimmunization to platelets is especially a problem in the cancer or bone marrow transplant patient population, as they are likely to require multiple transfusions over time. Transfusion reactions and infection are also risks that still should be taken into account. In addition, unlike other blood products, such as red blood cells, platelets can be quickly transfused immediately before or during the procedure.

As for neutropenia, it is more challenging to develop guidelines, as fewer studies are available. For those who are afebrile, antibiotics should be given prior to high risk procedures, such as ERCP with obstruction of the biliary tree, endoscopic dilatation, or variceal endoscopic treatment. For neutropenic patients requiring low risk endoscopic procedures, the endoscopist may consider antibiotics. Notably, patients who had fevers following endoscopy did not receive antibiotics in the reviewed studies. One may argue that if the ANC is less than 500/mm3, then antibiotics should be given regardless of the presence of fever. When administered, the antibiotics should cover gram-negative rods and anaerobes[20].

Authors of several studies have emphasized the effectiveness and importance of endoscopy when evaluating patients with GI symptoms, in spite of low platelet and neutrophil counts, considering the high diagnostic yield and low adverse event rate[21,22,26]. In one study that involved only eight endoscopies in 25 episodes of overt GI bleed, the authors expressed that endoscopy may not be necessary because GI bleeding was not the cause of death in these patients[27].

Limitations of this systematic review include the small number of available relevant studies, which required the use of older and/or small size studies. There was also a lack of consistency in study design among the included studies. Due to the nature of the search method, the data used may also reflect publication bias; most of the data were obtained through retrospective reviews.

Endoscopy can be safely performed in the settings of thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. Prophylactic platelet transfusion prior to endoscopy may be considered for platelet counts < 50000/mm3, although platelet counts below this threshold are not an absolute contraindication to endoscopy. We recommend prophylactic antibiotics in afebrile patients with neutropenia prior to high-risk endoscopic procedures. For low risk procedures in afebrile neutropenic patients, prophylactic antibiotics may be considered. Risks and benefits should be weighed in each individual scenario with thrombocytopenic and/or neutropenic patients who require endoscopic evaluation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Annilise LaRosa and Amy Pallotti for their assistance in formatting and submitting the manuscript.

COMMENTS

Background

There is limited data available regarding the safety and preventive measures prior to endoscopic procedures in cancer patients with thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines acknowledge that there is limited pertinent data, but recommend a platelet threshold of 20000/mm3 for diagnostic endoscopy and 50000/mm3 if biopsies are performed. British guidelines recommend ensuring platelet support is available before endoscopic intervention when platelet counts are below 50000-80000/mm3. Regarding neutropenia, the ASGE recommends that the decision to use antibiotics in patients with ANC < 500 should be individualized. British guidelines recommend antibiotic prophylaxis if ANC < 500/mm3 and a patient is undergoing a high-risk procedure. In this systematic review, a summary of the relevant studies is being presented. This article will help treating physicians consider diagnostic yield and safety of endoscopic procedures when facing these difficult cases, in addition to applying preventive measures when necessary.

Research frontiers

The majority of the relevant studies were retrospective. Future large prospective studies are needed. Currently, the data in the field is relatively limited, and any additional studies would help to solidify the recommendations regarding the safety of endoscopy in thrombocytopenic and neutropenic patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Investigating the safety of endoscopy in neutropenic and thrombocytopenic settings is an ever evolving process, to which new data will contribute to a better understanding and help us provide better care to our patients. The approach to advancing knowledge on this topic will likely be a gradual amalgamation of data.

Applications

Based on this systematic review, if endoscopic evaluation of a patient with thrombocytopenia is indicated, the procedure should not be withhold solely based on their platelet level. Platelet transfusion may be considered in some cases depending on the platelet count and the type of the procedure being performed. In afebrile neutropenic patients, we recommend prophylactic antibiotics prior to high-risk endoscopic procedures and consideration of antibiotics prior to low-risk procedures. Febrile neutropenic patients are mostly on antibiotic treatments that should be continued.

Peer-review

The topic investigated in this article is interesting. Nevertheless, studies included in this “systematic review” are very different in design and endpoints. The quality of the available data is poor, and it is very difficult (or impossible) to analyze them in a rigid framework, such as a meta-analysis, or even a systematic review.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 19, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

P- Reviewer: Camellini L, Moussata D S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans J, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fisher L, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Os EC, Kamath PS, Gostout CJ, Heit JA. Gastroenterological procedures among patients with disorders of hemostasis: evaluation and management recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:536–543. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rebulla P. Revisitation of the clinical indications for the transfusion of platelet concentrates. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2001;5:288–310; discussion 311-312. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-0734.2001.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samama CM, Djoudi R, Lecompte T, Nathan-Denizot N, Schved JF; Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé expert group. Perioperative platelet transfusion: recommendations of the Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé (AFSSaPS) 2003. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:30–37. doi: 10.1007/BF03018577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Khan K, Krinsky ML, Lichtenstein DR, Maple JT, Shen B, Strohmeyer L, Baron T, Dominitz JA. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razzaghi A, Barkun AN. Platelet transfusion threshold in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:482–486. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823d33e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yarris JP, Warden CR. Gastrointestinal bleeding in the cancer patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:363–379. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marwaha N, Sharma RR. Consensus and controversies in platelet transfusion. Transfus Apher Sci. 2009;41:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreyev HJ, Davidson SE, Gillespie C, Allum WH, Swarbrick E. Practice guidance on the management of acute and chronic gastrointestinal problems arising as a result of treatment for cancer. Gut. 2012;61:179–192. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Khashab MA, Chithadi KV, Acosta RD, Bruining DH, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Faulx AL, Fonkalsrud L, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Shaukat A, Wang A, Cash BD. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, Mullen CA, Raad II, Rolston KV, Young JA, Wingard JR; Infectious Diseases Society of Americaa. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:427–431. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison M, Bolger A, Cabell CH, Takahashi M, Baltimore RS, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139 Suppl:3S–24S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rey JR, Axon A, Budzynska A, Kruse A, Nowak A. Guidelines of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (E.S.G.E.) antibiotic prophylaxis for gastrointestinal endoscopy. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1998;30:318–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison MC, Sandoe JA, Tighe R, Simpson IA, Hall RJ, Elliott TS; Endoscopy Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2009;58:869–880. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.136580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bianco JA, Pepe MS, Higano C, Applebaum FR, McDonald GB, Singer JW. Prevalence of clinically relevant bacteremia after upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in bone marrow transplant recipients. Am J Med. 1990;89:134–136. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90289-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaw M, Przepiorka D, Sekas G. Infectious complications of endoscopic procedures in bone marrow transplant recipients. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:71–74. doi: 10.1007/BF01296776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu DZ, Shivshanker K, Stroehlein JR, Nelson RS. Thrombocytopenia and gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the cancer patient: prevalence of unmasked lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:269–272. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(83)72629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz JM, Wolford JL, Thornquist MD, Hockenbery DM, Murakami CS, Drennan F, Hinds M, Strasser SI, Lopez-Cubero SO, Brar HS, et al. Severe gastrointestinal bleeding after hematopoietic cell transplantation, 1987-1997: incidence, causes, and outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:385–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buderus S, Sonderkötter H, Fleischhack G, Lentze MJ. Diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy in children and adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;29:450–460. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2012.678568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorschlüter M, Schmitz V, Mey U, Hahn-Ast C, Schmidt-Wolf IG, Sauerbruch T. Endoscopy in patients with acute leukaemia after intensive chemotherapy. Leuk Res. 2008;32:1510–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park YB, Lee JW, Cho BS, Min WS, Cheung DY, Kim JI, Cho SH, Park SH, Kim JK, Han SW. Incidence and etiology of overt gastrointestinal bleeding in adult patients with aplastic anemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaur S, Cooper G, Fakult S, Lazarus HM. Incidence and outcome of overt gastrointestinal bleeding in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:598–603. doi: 10.1007/BF02282348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaur S, Ceballos C, Bao R, Pittman N, Benkov K. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes in pediatric bone marrow transplant patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:300–303. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318279444c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan K, Schwarzenberg SJ, Sharp H, Jessurun J, Gulbahce HE, Defor T, Nagarajan R. Diagnostic endoscopy in children after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:379–85; quiz 389-92. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross WA, Ghosh S, Dekovich AA, Liu S, Ayers GD, Cleary KR, Lee JH, Couriel D. Endoscopic biopsy diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease: rectosigmoid biopsies are more sensitive than upper gastrointestinal biopsies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:982–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulenburg A, Turetschek K, Wrba F, Vogelsang H, Greinix HT, Keil F, Mitterbauer M, Kalhs P. Early and late gastrointestinal complications after myeloablative and nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:101–106. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0756-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soylu AR, Buyukasik Y, Cetiner D, Buyukasik NS, Koca E, Haznedaroglu IC, Ozcebe OI, Simsek H. Overt gastrointestinal bleeding in haematologic neoplasms. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:917–922. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]