Highlights

-

•

A co-infection between influenza A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 was detected from a patient.

-

•

A reassortant A/H3N2 virus was isolated with a NS1 gene from A/H1N1pdm09.

-

•

The reassortant virus was viable and able to replicate in cell culture.

Keywords: Influenza, Seasonal, Co-infection, A/H3N2, A/H1N1pdm09, Reassortment, Reassortant

Abstract

Background

Despite annual co-circulation of different subtypes of seasonal influenza, co-infections between different viruses are rarely detected. These co-infections can result in the emergence of reassortant progeny.

Study design

We document the detection of an influenza co-infection, between influenza A/H3N2 with A/H1N1pdm09 viruses, which occurred in a 3 year old male in Cambodia during April 2014. Both viruses were detected in the patient at relatively high viral loads (as determined by real-time RT-PCR CT values), which is unusual for influenza co-infections. As reassortment can occur between co-infected influenza A strains we isolated plaque purified clonal viral populations from the clinical material of the patient infected with A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09.

Results

Complete genome sequences were completed for 7 clonal viruses to determine if any reassorted viruses were generated during the influenza virus co-infection. Although most of the viral sequences were consistent with wild-type A/H3N2 or A/H1N1pdm09, one reassortant A/H3N2 virus was isolated which contained an A/H1N1pdm09 NS1 gene fragment. The reassortant virus was viable and able to infect cells, as judged by successful passage in MDCK cells, achieving a TCID50 of 104/ml at passage number two. There is no evidence that the reassortant virus was transmitted further. The co-infection occurred during a period when co-circulation of A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 was detected in Cambodia.

Conclusions

It is unclear how often influenza co-infections occur, but laboratories should consider influenza co-infections during routine surveillance activities.

Background

The genomes of influenza A and influenza B viruses consist of eight separate negative-sense, single-stranded RNA segments. Both influenza A and influenza B viruses can rapidly evolve through reassortment of these RNA segments during co-infection. However, intertypic reassortment between influenza A and influenza B viruses has not been reported during natural infections [1].

Although seasonal influenza strains commonly co-circulate during epidemic periods, co-infections between influenza subtypes are rarely detected. Only a small number of publications have reported the detection of co-infections between seasonal influenza A strains [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. These events are important as they may result in reassortment of influenza viruses, leading to the circulation of novel epidemic strains. Reassortment between seasonal influenza viruses, A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09, may result in the emergence of influenza strains with increased transmission efficiency [7]. These viruses would be unlikely to have pandemic potential as they have emerged from currently circulating viruses and widespread immunity would limit their impact. However, outbreaks from recombinant A/H3N1 and A/H1N2 viruses have been detected in the past [5], [8]. During 2000–2002 an influenza A/H1N2 virus emerged which was a reassortant comprised of the HA from an A/H1N1 virus and all other genes from an A/H3N2 virus. This reassortant spread globally, and in some regions such as the United Kingdom and South Africa was the dominant A/H1 strain circulating in the 2001–2002 influenza season [9], [10].

Objectives

In this study we report the detection of an influenza co-infection which resulted in the generation of a reassortant progeny in a Cambodian patient presenting with influenza-like-illness (ILI) during April 2014.

Study design

During routine sentinel surveillance for ILI in 2014, the Cambodian National Institute of Public Health detected a co-infection between seasonal influenza strains. The co-infection, between influenza A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 (sample ID—Y0721354), was detected in April 2014 in a 3 year old male presenting to Kampong Cham Hospital with ILI. Viral RNA was detected in nasopharyngeal swab samples using real-time RT-PCR assays. The patient samples were referred to the Cambodian National Influenza Centre (NIC—Institut Pasteur in Cambodia, Virology Unit) for confirmation of results and further investigation.

At the NIC, viral RNA was extracted from nasopharyngeal swabs using the MagNa Pure LC system (Roche), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Seasonal influenza viruses were detected using real-time RT-PCR and conventional RT-PCR methods, as described previously [11], [12]. Real-time RT-PCR was used to give an indication of the relative viral loads of the co-infecting viruses in the clinical samples.

Plaque-purified clonal viral populations were isolated from the clinical material sampled from the patient with a H3N2/H1N1pdm09 co-infection. Briefly, confluent MDCK cells were infected with two-fold serial dilutions (1/10-1/1280) of clinical material and then overlaid with immunodiffusion grade agarose gel (MP Biomedicals). Following at least 3 days incubation at 37 °C, viruses were harvested from foci of infection and inoculated into fresh MDCK cells. Real-time RT-PCR and conventional RT-PCR methods [11], [12] were used to confirm the presence of HA1, HA3, NA1 and NA2 from seven plaque purified viruses. Sequence data were also generated for each gene fragment from plaque purified viruses to determine if reassortment of viruses had occurred. Amplified products for each gene fragment were sequenced directly using BigDye Terminator v3.1 chemistry using a Genetic Analyzer 3500xL sequencing machine (Life Technologies).

Results

Seasonal influenza viruses circulate throughout the year in Cambodia with peak seasonality occurring between June and November [11], [12]. Previous surveillance studies have established that multiple influenza viruses commonly co-circulate in the country, and co-infections have previously been detected [6]. The co-infection between influenza A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 viruses was detected in April 2014 and NIC surveillance data showed that both strains were circulating in Cambodia during this period (data not shown).

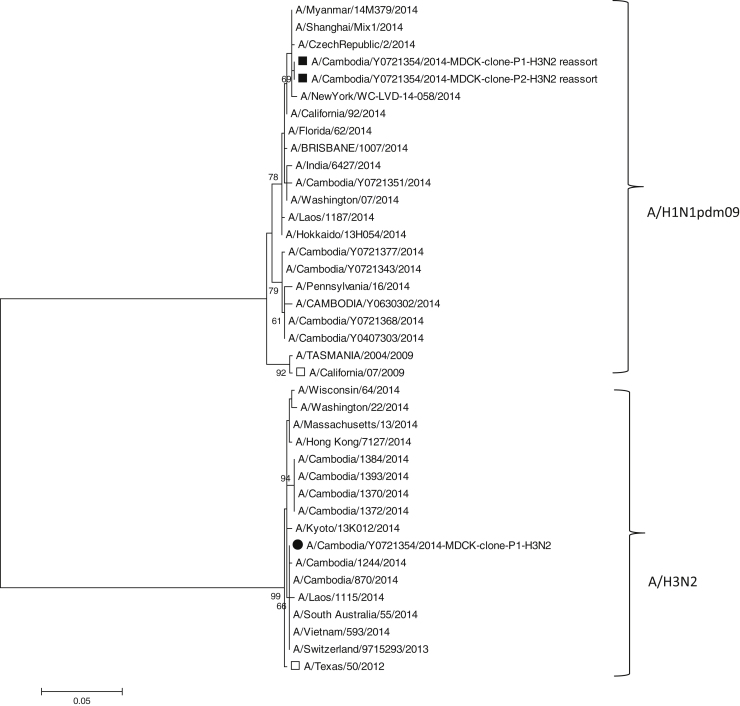

We used sequence analysis to screen plaque purified viruses for the presence of reassorted gene segments. One reassortant A/H3N2 virus was detected with the NS1 gene originating from A/H1N1pdm09 virus. Passage of the reassortant A/H3N2 virus showed that the virus was infectious, growing to a TCID50 of 104/ml after two sequential passages in MDCK cells. Sequence analysis of the HA, NA and NS1 genes of the passage 2 virus confirmed the presence of the reassortment in this virus with 100% sequence identity of the HA (Supplementary Fig. 1), NA (Supplementary Fig. 2) and NS1 genes (Fig. 1) to the first passage virus from the clonal plaque (sequence accession numbers in Supplementary Table). There is no evidence that the reassortant virus spread beyond the child presenting with the co-infection. However, as the screening for reassortants was not conducted until the samples were received at the NIC it was not possible to conduct further testing on other patients in the same area to determine if there was local spread of this virus.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on NS1 sequences of A/H1N1pdm09 and A/H3N2 viruses, generated in MEGA 6 [18] by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura 3-parameter model [19]. The numbers next to the branches indicate the percentage of 1000 bootstrap replicates that support each phylogenetic branch. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. (□) Vaccine strains in 2014: A/Texas/50/2012 (A/H3N2), A/California/07/2009 (A/H1N1pdm09). (■) A/H3N2 reassortant virus clone on MDCK cells, passage 1 and 2. (●) A/H3N2 virus clone on MDCK, passage 1.

Discussion

In previous instances where co-infections between influenza viruses have been detected, one strain is usually present at much higher concentration in the patient [3], [4], [5]. In the case described in this study both viruses were present at relatively high titres (Table 1). This situation increases the chances of co-infection of host cells occurring, leading to the possibility of reassortment of influenza viruses. The A/H3N2 reassortant detected in this study confirms that co-infections between influenza A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 viruses can produce infectious reassortants.

Table 1.

Crossing-threshold results obtained from real-time RT-PCR analysis of influenza co-infections.

| Sample | Influenza A M-gene (1) | Influenza A HA3 (2) | Influenza A NA2 (3) | Influenza A HA1pdm09 (3) | Influenza A NA1pdm09 (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y0721354 nasopharyngeal swab | 21.6 | 30.2 | 35 | 26.61 | 25.64 |

| Y0721354 MDCK clone P1 | 13.9 | 14.8 | 20.4 | Neg | Neg |

| Y0721354 MDCK clone P2 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 17.9 | Neg | Neg |

| H3N2 controla | 19.7 | 21.2 | 24.8 | Neg | Neg |

| H1N1pdm09 controlb | 19.7 | Neg | Neg | 20.9 | 22 |

CT values for HA3 and NA2 were consistent with results from routine testing of many A/H3N2 positive samples.

CT values for HA1 and NA1 were consistent with results from routine testing of many A/H1N1pdm09 positive samples.

We cannot discount that other reassorted viruses were present in the samples at lower frequencies than the dominant viral populations. The segmented nature of influenza viruses means that advanced genetic sequencing methods, such as high-throughput deep sequencing, are of no further benefit in detecting reassortments as it is not possible to determine which gene segments are associated with which virus. Seasonal influenza co-infections and resulting reassortments probably occur more often than has been previously documented. Recent in vivo experiments in guinea pigs with wild-type and mutated A/H3N2 viruses revealed that co-infection can result in high production of reassortant progeny [13]. Reassortment between A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 viruses perhaps occurs more rarely, but can result in viable progeny, as demonstrated by the A/H1N2 virus that achieved global circulation during 2000–2002 [9], [10]; and the isolation of a A/H1N2 reassortant between A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 in India during the 2009 pandemic [14]. The common practice of only targeting the HA and NA genes for RT-PCR and sequencing also probably results in many reassortments involving the internal genes being undetected.

Reassortment events can have important clinical implications, particularly for the generation of antigenically novel viruses. In 2006 our research group isolated an A/H1N1 strain with evidence of intrasubtypic reassortment, resulting in the generation of a virus with considerable amino acid changes relative to viral clustering based on the HA and other genes [15]. The emergence of such viruses may have significant impacts on the circulation of antiviral resistant strains. We have also previously documented reassortment between influenza A/H5N1 strains, which corresponded with a dramatic increase in human infections in Cambodia during 2013-2014 [16]. Co-infection between the avian influenza strain A/H7N9 and the seasonal influenza strain A/H3N2 has previously been documented in China [17]. The endemic circulation of A/H5N1 and A/H7N9 in the region, in addition to the presence of a myriad of other avian influenza viruses, raises the very real possibility of co-infection and reassortment between avian and seasonal influenza viruses, resulting in the possible emergence of a new pandemic virus. It is essential that influenza surveillance capacities are further strengthened in the region to monitor the evolution of these viruses.

Competing interests

The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all of the co-authors. We declare that we have no financial or personal conflicts of interest for the publication of this article.

Funding

The activities of the Cambodian National Influenza Centre at the Institut Pasteur in Cambodia were supported by theWorld Health Organization office in Cambodia. The activities of the National Institute of Public Health were supported by the Cambodian Ministry of Health and US CDC, Cooperative Agreement U51IP000522.

Ethical approval

Influenza-like-illness and event-based surveillance systems are public health activities organized by the Ministry of Health in Cambodia and as such have a standing authorization from the National Ethics Committee.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2015.11.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Baker S.F., Nogales A., Finch C., Tuffy K.M., Domm W., Perez D.R., Topham D.J., Martínez-Sobrido L. Influenza A and B virus intertypic reassortment through compatible viral packaging signals. J. Virol. 2014;88:10778–10791. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01440-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendal A.P., Lee D.T., Parish H.S., Raines D., Noble G.R., Dowdle W.R. Laboratory-based surveillance of influenza virus in the United States during the winter of 1977–1978 II. Isolation of a mixture of A/Victoria- and A/USSR-like viruses from a single person during an epidemic in Wyoming U.S.A., January 1978. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1979;110:462–468. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falchi A., Arena C., Andreoletti L., Jacques J., Leveque N., Blanchon T., Lina B., Turbelin C., Dorléans Y., Flahault A., Amoros J.P., Spadoni G., Agostini F., Varesi L. Dual infections by influenza A/H3N2 and B viruses and by influenza A/H3N2 and A/H1N1 viruses during winter 2007, Corsica Island, France. J. Clin. Virol. 2008;41:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee N., Chan P.K., Lam W.Y., Szeto C.C., Hui D.S. Co-infection with pandemic H1N1 and seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010;152(9):618–619. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu W., Li Z.D., Tang F., Wei M.T., Tong Y.G., Zhang L., Xin Z.T., Ma M.J., Zhang X.A., Liu L.J., Zhan L., He C., Yang H., Boucher C.A., Richardus J.H., Cao W.C. Mixed infections of pandemic H1N1 and seasonal H3N2 viruses in 1 outbreak. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50:1359–1365. doi: 10.1086/652143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers C.A., Kasper M.R., Yasuda C.Y., Savuth C., Spiro D.J., Halpin R., Faix D.J., Coon R., Putnam S.D., Wierzba T.F., Blair P.J. Dual infection of novel influenza viruses A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 in a cluster of Cambodian patients. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;85:961–963. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komadina N., McVernon J., Hall R., Leder K. A historical perspective of influenza A(H1N2) virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:6–12. doi: 10.3201/eid2001.121848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizuta K., Katsushima N., Ito S., Sanjoh K., Murata T., Abiko C., Murayama S. A rare appearance of influenza A(H1N2) as a reassortant in a community such as Yamagata where A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) co-circulate. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003;47(5):359–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis J.S., Alvarez-Aguero A., Gregory V., Lin Y.P., Hay A., Zambon M.C. Influenza AH1N2 viruses, United Kingdom, 2001–02 influenza season. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003;9:304–310. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen M.J., La T., Zhao P., Tam J.S., Rappaport R., Cheng S.M. Genetic and phylogenetic analysis of multi-continent human influenza A(H1N2) reassortant viruses isolated in 2001 through 2003. Virus Res. 2006;122:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mardy S., Ly S., Heng S., Vong S., Huch C., Nora C., Asgari N., Miller M., Bergeri I., Rehmet S., Veasna D., Zhou W., Kasai T., Touch S., Buchy P. Influenza activity in Cambodia during 2006–2008. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009;9:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horm S.V., Mardy S., Rith S., Ly S., Heng S., Vong S., Kitsutani P., Ieng V., Tarantola A., Ly S., Sar B., Chea N., Sokhal B., Barr I., Kelso A., Horwood P.F., Timmermans A., Hurt A., Lon C., Saunders D., Ung S.A., Asgari N., Roces M.C., Touch S., Komadina N., Buchy P. Epidemiological and virological characteristics of influenza viruses circulating in Cambodia from 2009 to 2011. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao H., Li L., White M.C., Steel J., Lowen A.C. A Influenza virus coinfection through transmission can support high levels of reassortment. J. Virol. 2015;89:8453–8461. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01162-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukherjee T.R., Agrawal A.S., Chakrabarti S., Chawla-Sarkar M. Full genomic analysis of an influenza A (H1N2) virus identified during 2009 pandemic in Eastern India: evidence of reassortment event between co-circulating A(H1N1) pdm09 and A/Brisbane/10/2007-like H3N2 strains. Virol. J. 2012;9:233. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fourment M., Mardy S., Channa M., Buchy P. Evidence for persistence of and antiviral resistance and reassortment events in seasonal influenza virus strains circulating in Cambodia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:295–297. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01687-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rith S., Davis C., Duong V., Sar B., Horm S., Chin S., Ly S., Laurent D., Richner B., Oboho I., Jang Y., Davis W., Thor S., Balish A., Luliano D., Holl D., Sorn S., Sok T., Seng H., Tarantola A., Tsuyuoka R., Parry A., Chea N., Allal L., Kitsutani P., Waren D., Prouty M., Horwood P., Widdowson M.A., Lindstrom S., Villanueva J., Donis R., Cox N., Buchy P. Identification of molecular markers associated with alteration of receptor-binding specificity in a novel genotype of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses detected in Cambodia. J. Virol. 2014;88 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01887-14. 13897-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y., Qi X., Cui L., Zhou M., Wang H. Human co-infection with novel avian influenza A H7N9 and influenza A H3N2 viruses in Jiangsu province, China. Lancet. 2013;381:2134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition–transversion and G + C-content biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992;9:678–687. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.