Abstract

Background

Advocacy is often described as a pillar of the medical profession. However, the impact of advocacy training on medical students’ identity as advocates in the medical profession is not well-described.

Aim/Setting/Participants

We sought to introduce an advocacy curriculum to a mandatory Health Care Disparities (HCD) course for 88 first year medical students.

Program Description

The 2013 HCD added advocacy curriculum that included: guest lecturers’ perspectives on their advocacy experience; reflective essay assignments assessing self-identify as an advocate; advocacy-specific lectures and large group discussions; and participation in small group community projects.

Evaluation

A mixed methods approached was used to evaluate 88 first year medical students’ advocacy themed reflective essays, independently coded by three investigators, and Likert-response questions were compared to published benchmarked items. The IRB exempted this study. Analysis of student essays revealed that students were better able to identify as an advocate in medicine. The survey also revealed that 86% post-course vs. 73% precourse agreed/strongly agreed with the statement: “I consider myself an advocate” (p=0.006).

Discussion

Exposing all medical students to advocacy within medicine may help shape and define their perceived professional role. Future work will explore adding advocacy and leadership skill training to the HCD course.

Keywords: Medical Education, Advocacy Training, Underserved, Access to Care, Social Justice, Social Responsibility

INTRODUCTION

Every fall, incoming medical students take the Hippocratic Oath during white coat ceremonies across the US and state that they: “will be an advocate for patients in need and strive for justice in the care of the sick [1].” One broad definition of physician advocacy is: action by a physician to promote those “social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being….” [2] Further, several medical societies endorse concepts of advocacy, social responsibility and social justice, including the American Medical Association’s Declaration of Professional Responsibility [3] and the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Physician Charter. [4]

Despite such endorsements by medical societies, advocacy education and training is not a mandatory component of medical training at the majority of US medical schools. Therefore, it is not surprising that few examples of medical school advocacy training have been published. One such example is the Leadership Education Advocacy Development Scholarship (LEADS) program led by Jeremy Long and colleagues at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine [5]. The LEADS program is offered as an elective track to medical students focused on advocacy skills and community-based service learning. The LEADS program has successfully increased student empowerment and tendency toward community service [5].

While the LEADS program reported promising results as an elective course, students not electing to take the course may not receive advocacy based education. Mandatory exposure to advocacy and social responsibility is important to consider if these concepts are so widely accepted, and possibly expected, of our profession. One program that may prepare students to become advocates is the mandatory multicultural education curriculum at the University of Michigan that aims to develop an orientation or “critical consciousness” placing medicine in a “social, cultural, and historical context” to help search for solutions to societal problems.[6] The authors of the University of Michigan’s curriculum paper note that “there is a distressingly common failure to connect the idea of diversity with the underlying core concept of social justice in healthcare.”[6]

At the Pritzker School of Medicine, first-year students complete a mandatory Health Care Disparities Course (HCD) [7]. This HCD course provides an ideal opportunity for new medical students to learn about social determinants, underserved populations, and health care inequities, connecting concepts of diversity, equity, and social justice. Therefore, in 2013, HCD course was modified to include advocacy-specific learning. Definitions of advocacy vary by individual and groups of professionals and can be broad or more specific. Therefore, the overall aim of this initial curricular change was to help develop a framework for how advocacy could and should be taught at Pritzker. In order to accomplish this, we sought to first assess our students’ prior experience with, understanding of, and definitions of advocacy. Therefore, there were three main objectives of this course modification and study: 1) to explore students’ understanding of advocacy in medicine prior to the course; 2) to provide a structure for students to explore advocacy and their commitment to advocacy; and 3) to help first-year medical students begin to define themselves as advocates within the profession of medicine. The objective of this paper is to describe the evolution of students’ identity as medical advocates after adding a mandatory advocacy curriculum to the HCD course.

METHODS

Course description

Traditionally, HCD has been a 10-week course provided to first-year medical students consisting of inter-professional guest lectures, small-group projects, and a community expedition to the local public hospital [7].

Addition of Advocacy to Curriculum

An advocacy curriculum component was added to the traditional HCD course activities in 2013. The course name was changed to HCD: Advocacy and Equity. Advocacy-specific lectures and seminars were introduced to explore the breadth and depth of medical advocacy. Invited experts lectured across multiple disciplines, including health policy, education, and sociology, along with medicine, public health and public education and delineated their perspectives and experiences with advocacy during their lecture time. These personal perspectives helped to reinforce the complexity of defining medical advocacy across disciplines. Essay assignments encouraged students’ self-reflection about advocacy within the profession and self-identifying as an advocate.

Students also completed small-group community-based projects mentored by faculty and supervised by fourth year medical student teaching assistants. Examples of these community-based projects include mapping community resources of a local growing Laotian population, establishing a student run early literacy promotion program, and educating local community groups on the basics of the Affordable Care Act and how to enroll in an insurance plan. These small group projects highlighted the need to work inter-professionally and collaboratively in teams.

Data collection

This was a mixed methods study combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Students were surveyed pre-course and post- course. All pre/post comparative items were matched and de-identified. All surveys were completed online and submitted to a project manager, who then forwarded de-identified data to the investigators. This study was IRB exempt (IRB13-0971).

Study instruments

Pre/post survey reflective essays

Short reflective essays prompted by open-ended questions allowed for exploration of topic areas and ultimate development of themes [8]. Each reflective essay assignment was iteratively designed based on previous responses and in-class discussion. The pre-course survey included 7 short reflective-essay items; the post-course survey included 3 such items. Questions included “How has your understanding of advocacy in medicine changed since taking this course?”

Pre/post survey discreet-answer survey questions: Self-definition as advocate and access to health care (Table 1)[9–12]

Table 1.

Pre/Post Course Survey

| Item | Pre | Post | p * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strongly disagree/ disagree |

neutral | agree/ strongly agree |

strongly disagree/ disagree |

neutral | agree/ strongly agree |

||

| Self-definition as advocate | |||||||

| I consider myself an advocate | 3.4 | 23.9 | 72.7 | 3.4 | 10 | 86 | 0.006 |

| Attitudes about Access to Care† | |||||||

| Physicians have a responsibility to take care of patients regardless of their ability to pay.† | 2.2 | 8 | 90 | 5.7 | 6.8 | 87.5 | 0.352 |

| Access to basic health care is a fundamental human right.† | 5.7 | 1.1 | 93.2 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 94 | 0.317 |

| Managed care, as it is now delivered, is a good way to deliver health care to the U.S. population.† | 47.7 | 44.3 | 8 | 50 | 37.5 | 12.5 | 0.561 |

| Attitudes toward the Underserved | |||||||

| All medical students should become involved in community health efforts.‡ | 9.1 | 28.4 | 62.5 | 19.3 | 27.3 | 53.4 | 0.134 |

| Medical students should be involved in providing medical care for the needy§ | 1.1 | 15.91 | 83 | 8 | 28.4 | 63.6 | 0.005 |

| Society is responsible for providing for the healthcare of its members‡ | 1.1 | 13.8 | 85.1 | 3.4 | 9.2 | 87.4 | 0.284 |

| I would be interested in volunteering for programs that provide medical care for the underserved during my medical school experience§ | 2.3 | 2.3 | 95.5 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 93.2 | 0.223 |

| I personally want to be involved in providing care for the underserved during my medical career§ | 1.1 | 9.1 | 89.8 | 0 | 6.8, | 93.2 | n/a |

| I feel personally responsible for providing medical care to the needy‖ | 2.3 | 11.4 | 86.4 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 88.4 | 0.261 |

| Medical care should be provided without charge for those who cannot pay‖ | 9.1 | 22.7 | 68.2 | 5.7 | 15.9 | 78.4 | 0.284 |

| Physicians should volunteer their time working in a free clinic‖ | 1.1 | 37.9 | 61.4 | 8 | 34.1 | 58 | 0.099 |

| Personal access to health care | |||||||

| I have a right to health care regardless of my ability to pay | 8 | 4.5 | 87.5 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 88.6 | 0.549 |

McNemars test

Frank E, Modi S, Elon L, Coughlin SS. U.S. medical students' attitudes about patients' access to care. Prev Med. 2008 Jul;47(1):140–5.

Wayne S, Timm C, Serna L, Solan B, Kalishman S. Medical students' attitudes toward underserved populations: changing associations with choice of primary care versus non-primary care residency. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010 May;21(2):438–47. Note: adapted from original “physicians”, ours “medical students”

Crandall SJS. Medical student attitudes toward caring for the medically underserved. In: Proceedings of the 20th Annual Standing Conference on University Teaching and Research in the Education of Adults; 1990; Sheffield, England. Pages 184–190. Note: adapted from original “physicians”, ours “medical students”

Crandall SJ, Davis SW, Broeseker AE, Hildebrandt C. A longitudinal comparison of pharmacy and medical students' attitudes toward the medically underserved. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008 Dec 15;72(6):148.

The pre/post-course survey included thirteen items (Likert scale 1–5: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5); they were further categorized into disagree (1 or 2), neutral (3) and agree (4 or 5)). Items were matched and de-identified for comparison. When available, these discreet answer questions were benchmarked against questions previously validated and published in the literature [9–12].

Attitudes about patients’ access to care [9] [Table 1]

Questions originally published by Erica Frank and colleagues in 2008 were utilized as a benchmark for our pre/post-course surveys to assess attitudes about patients’ access to care.[9] These included the items, “physicians have a responsibility to take care of patients regardless of their ability to pay” and “access to basic health care is a fundamental human right.” [9]

Attitudes toward Underserved Populations [10–12] [Table 1]

Previously validated questions in studies by Wayne et al [10] and Crandall et al [11–12] about medical students’ attitudes toward underserved populations were also utilized in our pre/post-course survey, again providing a benchmark by which to compare our students’ responses to the published literature. [10–12] Examples include: “Medical care should be provided without charge for those who cannot pay”; [10] “I would be interested in volunteering for programs which provide medical care for the needy”; [11] and “Physicians should volunteer their time working in a free clinic.”[12]

Self-definition as Advocate and Personal access to health care

Finally, to assess students’ attitudes about their own definition as advocate and access to care, we asked: “I consider myself an advocate” and “I have a right to health care regardless of my ability to pay.”

Analysis

Qualitative analyses were completed by three masked investigators (VGP, CDLF, MBV). Data analysis was conducted iteratively guided by grounded theory [13–14]. The investigators met to develop coding schemes; short answer essays were coded independently by each investigator. Coding responses were compared; any nonunanimous item was discussed until consensus was achieved. Themes were developed based on the coding results. Quantitative analyses comparing pre-course vs. post-course response utilized McNemars test. All testing was performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 at a two-sided significance level of p<0.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-five mandatory lectures, 1–2 hours long, were given by 28 invited experts across multiple disciplines, including health policy, education, and sociology, along with medicine, public health and public education. Each of the 28 lecturers for the course was asked to delineate their perspectives and experiences with advocacy during their lecture time (100% complied with this request). The lectures represented more than a dozen disciplines and professions. The 11 small group projects incorporated at least one of these disciplines in their approach to advocacy through community service (Tables 2–3).

Table 2.

Small group projects and field of discipline

| Small group project | Fields(s) |

|---|---|

| Pediatric Access to Mental Health Care on the South Side of Chicago | Community health/ Public policy/ Psychology, |

| Community Asset Mapping for Lao Americans in Elgin, IL | Community health/ Public Health/ Sociology |

| Physician Perceptions of Healthcare Transitions for Patients with Childhood Onset Chronic Diseases | Medicine/ Sociology |

| A Novel Survey to Assess Medical Spanish Fluency and Detect False Fluency in Medical Students | Communication |

| Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to Analyze Colorectal Cancer Disparities in Chicago | Community health/ Public Health/ Health Services Research |

| Investigating Barriers to HIV Testing and Healthcare in Minority and Black MSM | Community health/ Public Health |

| Medical Student Volunteerism in Chicago Public Schools | Education / Community health |

| Developing a Model to Establish and Sustain a Reach out and Read (ROR) Program | Education / Community health |

| Assessing Access to Psychiatric Care for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities on Chicago’s South Side: a Pilot Study | Community health/ Psychology, |

| Identifying Barriers to the Pediatric-Adult Transition of Care in Gastroenterology Patients | |

| The Impact of the Affordable Care Act on the South Side of Chicago: A Community Education Project | Law/ Public policy |

Table 3.

Lecture titles and field of discipline

| Lecture title | Field(s) |

|---|---|

|

Bioethics/Medical Ethics |

|

Communication |

|

Community health/Administration |

|

Education /Education administration |

|

History |

|

Health Services Research |

|

Law/ Public policy |

|

Medicine/public policy |

|

Nursing /Nursing administration |

|

Public Health /Public health administration |

|

Psychology/Sociology |

One student stated about the lectures: “For me, the lectures where these types of issues were discussed were particularly meaningful, such as the lecture on homelessness and transitional care, or the lecture on healthcare disparities faced by the LGBTQ community, specifically the understanding as a clinician that in seeing a LGBTQ patient you may have to ask different questions.” Another student stated about the lectures: “I found the most revealing moments from the class have come as a result of the ability of the speaker to share something personal or to tell a coherent story.”

In terms of the small group project, on student said: “my health care disparities project of mapping the Laotian population in Elgin showed me the importance of identifying health care resources for vulnerable populations and increasing access to these resources. Prior to this course, I thought much less about some aspects of increasing access to resources such as adequate public transportation as a part of advocacy. … Thus, I believe this course has expanded my definition of medical advocacy in quite a profound way.”

Outcomes

Pre-course assessment

The pre-course survey was completed by all 88 students. Prior to entering medical school, the vast majority of students (93%) had experience working with underserved populations; three-quarters (77%) spent >15 hours on this activity. Just over half (53%) said that they or someone they knew had faced a health or health care disparity.

Advocacy within the profession of medicine

Prior to course completion, 73% of students identified as advocates, 24% were neutral, and a minority (3%) did not identify as advocates in medicine. Students defined advocacy as the process of advocating for policy issues, rights, causes, reform, and interests (38%), increased access and affordability of health care (24%), improving health and health care (21%), changes in systems, public health, and/or quality of care (16%), and improving treatments (10%).

Post-course assessment

Advocacy identify within the profession of medicine

Post-course, 86% considered themselves advocates versus 73% pre-course (p=0.006); notably students who changed their perspective were originally “neutral” (24% pre vs. 10% post).

Call to advocacy

Almost all of the students (95%) reported that “my personal experiences call me to advocacy.” Responses to “what calls you to advocacy within the profession of medicine” included personal experience and non-experiential sources.

Personal experience

Half (52%) reported a personal experience as a member of an underserved community or personally witnessing a disparity suffered by a local underserved community. For instance, one student was motivated by their personal experience as a child: “I recall serving food at leprosy colonies in India with my family.” Of these students, 22% reported belonging to an immigrant family that underwent a transition in health, health care status, availability in health care resources, or education upon immigrating to the United States. One student stated: “My parents emigrated from a war-torn region of the world to start a new life here in the United States…My family was a product of the American dream. However, what I have come to realize is that the American Dream has been reduced to a vicious cycle of poverty and illness for many people in this country.” Another 22% reported that their religion, race, or class status directly impacted their call to advocacy. One student shared, “I’m called to advocacy because being black in America shouldn’t be this hard.” Twenty-percent reported that a sense of recognition of advocacy efforts on their behalf motivated their sense of advocacy for others.

Non-experiential source

Just under half (44%) reported non-experiential sources of motivation for their advocacy interests; 26% reported main drivers for advocacy were a personal sense of moral responsibility or social justice and a commitment to equity and fairness, while 24% reported their motivation as an awareness of disparities. One student noted, “Learning about health disparities through this course has caused me to shuffle through my past in a positive way to think about why I want to be an advocate.” Some students engage in advocacy because of joy or satisfaction (16%), while others reported that societal expectations served as inspiration (13%). Twenty-four percent reported that advocacy is integral to the medical profession and inherent to a physician’s duty.

Non-advocates or ambivalence about role as advocate

A handful of students (n=7) either did not feel called to advocacy or had ambivalence about their self-definition as advocates. Four mentioned that no societal burden or call from a professional society would inspire them to advocacy efforts.

Changes in understanding of advocacy in medicine post-course

After completing the course, students were asked to discuss how their understanding of advocacy in the profession of medicine had changed over the 10 weeks. Over one-half (53%, 46/88) wrote that their understanding of advocacy broadened and expanded beyond their previously limited definition that included either only political advocacy or advocacy at the level of the provider-patient. Students acknowledged post-course that the advocacy role is multi-tiered and may include the patient, the patient’s community, and more global settings. Another 22% (19/88) stated they learned about the great variety of mechanisms employed in advocacy efforts beyond policy work, including research efforts, educational reform, and housing reform.

Students also noted that their eyes were opened to the importance of collaborating with community members, lawyers, and other professionals outside the realm of the medical profession (15%, 13/88); 12% were excited about the role that research could play in advocating for patients and health care. Students also noted feeling more empowered to engage in advocacy (28%, 24/88) and that the course helped them to develop or further define their role in advocacy (34%, 30/88).

One student summarized lessons learned about advocacy in the course by stating: “the greatest lesson I learned about advocacy in medicine through this course is that there is no single definition of advocacy and that we owe numerous advancements in population healthcare and innovative healthcare and social initiatives to the different interpretations of advocacy that dynamic people inside and outside of the healthcare profession have envisioned.” This statement was encouraging that we were successful in not imposing a single definition of advocacy through the course.

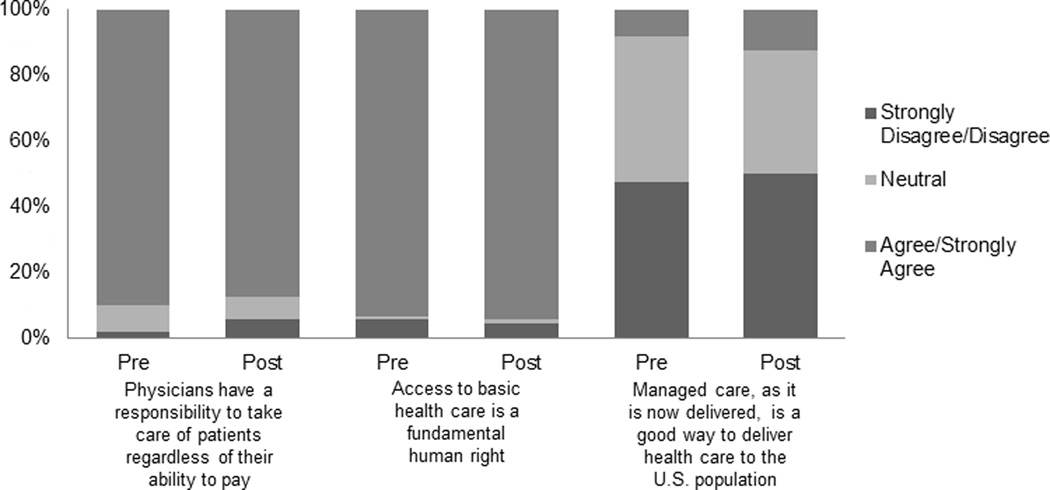

Attitudes about Access to Care (Table 1)

Prior to the course, 90% of students believed that physicians have a responsibility to take care of patients regardless of their ability to pay, and 93% believed that access to basic health care is a fundamental human right. However, only 8% believed that managed care is a good way to deliver health care. After completing the course, there were no significant changes in students’ responses to questions about access to care (88%, 94%, 13% respectively; p=NS for all items). Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Attitudes about Access to Care.9

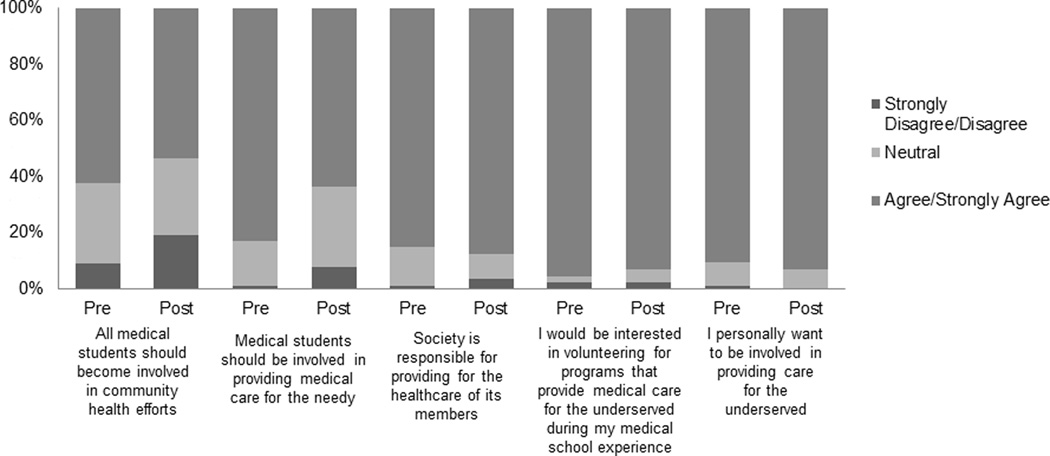

Attitudes toward the Underserved (Table 1)

Prior to completing the course, students’ attitudes toward providing and/or paying for medical care were mixed: Eight-five percent of students believed that society is responsible for providing for the healthcare of its members. However, when it came to paying for care, 88% of students believe that they “have a right to health care regardless of my ability to pay,” while only 68% of students believe that medical care should be provided without charge for those who cannot pay. After completing the course, attitudes toward the underserved were largely unchanged (87%, 89%, 78%, p=NS for all items). Figure 2.

Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Our advocacy curriculum was innovative in that it was mandatory for all incoming Pritzker students. Therefore our results were informed by all students, not just those who may have been more inclined toward the subject. The HCD course provided an ideal format of guided learning in which to explore medical students’ understanding of and commitment to advocacy in medicine through experiential learning activities and self-reflective assignments.

Given these parameters, we were able to draw some interesting conclusions. First, introducing advocacy training into the HCD course seemed to have an effect on some students’ identity as advocate, but not on others. For instance, several students who were initially “neutral’, re-defined themselves as advocates by the end of the course. This change may speak to the benefit of mandatory coursework on advocacy. Elective coursework is unlikely to capture students who are neutral or have a poorly defined sense of medical advocacy. One student stated: “Before entering medical school, there were many people telling me physicians could not be effective advocates because they just do not have the time, reimbursement rates are down, other professions are better suited for it, etc. However, one thing this course showed is that physicians can provide excellent patient care and also engage in life-changing advocacy. You do not have to sacrifice career goals to be an advocate. In fact, being an advocate has become something I know I want to have in my developing career. Regardless of the specialty I go in to, I hope to use my educational and experiential background to be a strong and effective advocate.”

Even students who already defined themselves as advocates before the course found that their understanding of advocacy was enhanced and their commitment was strengthened. Another statement noted: “However, it is important to note that becoming an advocate does not just happen naturally over the course of a career. That is to say, one needs to actively make advocacy a priority to truly impact the lives of those around you. I appreciate how the Healthcare Disparities course introduced us to concepts of advocacy very early in our medical education so that they can remain a priority as we develop and mature as physicians. I firmly believe that advocacy cannot simply be an afterthought, not simply something we do ‘if there is time’”.

However, students who did not define themselves as advocates prior to the course remained unchanged after completing the course. This occurred despite our efforts to allow students to define advocacy for themselves and not enforcing a narrow definition of medical advocacy. Therefore, mandatory advocacy training may be necessary, but not sufficient, for a goal of ensuring that all physicians identify and serve as advocates.

Further, it is important to note that while only 86% of student consider themselves as ‘advocates’ at the conclusion of the course, 95% of students stated that their personal experiences called them to advocacy. While this may seem like a discrepancy in the data, these differing responses could be due to the conflict that some students feel with respect to defining themselves as advocates. For instance, some students may want to advocate and/or be called to advocate, without feeling empowered to be an advocate. One student stated: “Although I do not yet possess the entire toolset needed to efficiently advocate as a medical provider, this class has taught me that I do not have to practice medicine to become an advocate.” Another reason may be with the semantics of the word advocacy. Here are one student’s thoughts: “’advocacy’ does not seem to me to fully capture this approach to addressing inequalities in population health. I think of advocacy as literally speaking out or speaking up for a certain cause, where as I think that the approach that I have described above, which is practiced by many of our speakers, is a more encompassing approach that includes identifying, testing, and intervening, not just raising one’s voice. I don’t have a better term for it, but “advocacy” seems to somehow undersell and nebulize the work that is being done on these topics.” Finally, some students did not change their own self-definitions of being advocates but still gained increased their awareness about the breadth of the term: “Overall, I do not think that Healthcare Disparities class has changed whether or not I want to be an advocate to my patients, but it has taught me all the different ways the term can be applied and how I can pursue it in my career.”

Our study has imitations. This course took place at a single institution, without a comparator group, and with a relatively small sample size. Further, in this iteration of the innovation we did not provide advocacy skills-specific training; these efforts are the basis of the next iteration of the curriculum innovation. Also important to note, the Pritzker admissions committee does require matriculating students to provide evidence in their application of significant service experience, which may have skewed the number of students with social justice inclinations prior to taking HCD. Further, we realize that this makes the class unique, with the majority of students entering medical school with positive attitudes toward the undeserved. This uniqueness may limit the generalizability, and therefore, cohorts that do not share these attributes may not realize similar gains.

Despite these limitations, our project provided some important insights. Our course provided an ideal format of guided learning in which to explore medical students’ understanding of, and commitment to, advocacy in medicine through experiential learning activities and self-reflective assignments. Reflective essays revealed that students’ fundamental societal views are largely formed prior to medical school by personal experiences. Finally, mandatory training in advocacy helps to identify students who are ambivalent about their role in advocacy and provides an opportunity to address the ambivalence in a way that elective course work may not. Future work will explore adding advocacy and leadership skill training to our HCD course.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the University of Chicago PSOM. We would like to thank Michael McGinty who was invaluable as the project manager. We would also like to thank Augie Kimble for his audio-visual expertise. We would like to thank our esteemed guest lecturers, teaching assistants, and hosts at Cook County for their invaluable role in the success of implement the curriculum. Finally, we would like to thank the PSOM first year medical students for engagement and feedback without which we could not have implemented and evaluated the advocacy curriculum.

Funding/Support: Dr. Press receives funding from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (1K23HL118151-01).

Footnotes

Previous Presentations: This work has been presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine annual meeting in April 2014, the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine annual meeting in September 2014, and the AAMC Medical Education Meeting in November 2014.

Disclosures

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Press, Mrs. Fritz, and Dr. Vela declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research involving human participants: This study was given an exempt determination by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Informed Consent: Participants participated in de-identified online surveys. An explanation of the project and IRB exemption number were provided prior to the start of the survey.

Contributor Information

Dr. Valerie G. Press, Section of Hospital Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Ms. Cassandra D. L. Fritz, Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago IL.

Dr. Monica B. Vela, Section of General Internal Medicine/Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago IL.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Hippocratic Oath. [Accessed February 2, 2014]; Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html.

- 2.Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Physician advocacy: What is it and how do we do it? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):63–67. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Medical Association. Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine's Social Contract With Humanity. [Accessed February 2, 2014]; Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/ethics/decofprofessional.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Board of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–246. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long JA, Lee RS, Federico A, Battaglia C, Wong S, Earnest M. Developing leadership and advocacy skills in medical students through service learning. J Public Health Management Practice. 2011;17(4):369–372. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182140c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumagi AK. beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice and mutlicutlural education acad med. 2009;84:782–787. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vela MB, Kim KE, Tang H, Chin MH. Innovative health care disparities curriculum for incoming medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Jul;23(7):1028–1032. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0584-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross PT, Williams BC, Doran KM, Lypson ML. First-year medical students' perceptions of physicians' responsibilities toward the underserved: an analysis of reflective essays. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(9):761–765. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30672-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank E, Modi S, Elon L, Coughlin SS. U.S. medical students' attitudes about patients' access to care. Prev Med. 2008;47(1):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wayne S, Timm C, Serna L, Solan B, Kalishman S. Medical students' attitudes toward underserved populations: changing associations with choice of primary care versus non-primary care residency. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2):438–447. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crandall SJS. Medical student attitudes toward caring for the medically underserved; Proceedings of the 20th Annual Standing Conference on University Teaching and Research in the Education of Adults; Sheffield, England. 1990. pp. 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crandall SJ, Davis SW, Broeseker AE, Hildebrandt C. A longitudinal comparison of pharmacy and medical students' attitudes toward the medically underserved. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):148. doi: 10.5688/aj7206148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]