Abstract

Estrogen-related receptor alpha (ESRRa) regulates a number of cellular processes including development of bone and muscles. However, direct evidence regarding its involvement in cartilage development remains elusive. In this report, we establish an in vivo role of Esrra in cartilage development during embryogenesis in zebrafish. Gene expression analysis indicates that esrra is expressed in developing pharyngeal arches where genes necessary for cartilage development are also expressed. Loss of function analysis shows that knockdown of esrra impairs expression of genes including sox9, col2a1, sox5, sox6, runx2 and col10a1 thus induces abnormally formed cartilage in pharyngeal arches. Importantly, we identify putative ESRRa binding elements in upstream regions of sox9 to which ESRRa can directly bind, indicating that Esrra may directly regulate sox9 expression. Accordingly, ectopic expression of sox9 rescues defective formation of cartilage induced by the knockdown of esrra. Taken together, our results indicate for the first time that ESRRa is essential for cartilage development by regulating sox9 expression during vertebrate development.

Estrogen-related receptors (ESRRs), an orphan nuclear receptor family, were originally identified due to sequence similarity with estrogen receptors (ERs), and accordingly share many target genes with ERs1,2,3. However, ESRRs are not responsive to estrogen and their ligands are yet to be discovered. Recent studies indicate that members of ESRRs participate in a number of biological processes including metabolism, reproduction, and development4. In particular, ESRR alpha (ESRRa) and ESRR gamma (ESRRg) are key metabolic regulators of energy homeostasis, and abnormal functions of these proteins are linked to metabolic syndromes including diabetes and fatty liver disease5. The role of ESRRa in cellular metabolism is largely dependent on its transcriptional regulation of mitochondrial function and biogenesis through collaboration with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1 alpha (PGC1a)6. Beside PGC1a/b, ESRRa has been shown to potentiate a metabolic syndrome by acting downstream of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)7 and also promotes hypoxic adaptation of cancer cells by stabilizing hypoxia inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1-a) from degradation8. These reports together with other studies solidify the role of ESRRa in maintaining energy homeostasis.

The role of ESRRs during animal development may also be linked to metabolic regulation by which developing embryos meet their high energy demand for growth. A complex expression pattern of ESRRs during animal development seems to be consistent with the potential roles for ESRRa during appropriate developmental programs of tissues and organs in mouse and zebrafish9. However, aside from muscle development, the roles of ESRRs in other tissues including bone and cartilage have just begun to be investigated10. During bone development, ESRRs are shown to be involved in differentiation and function of osteoblasts and osteoclasts with potential involvement of PGC1 (reviewed in11). A potential role for ESRRa in chondrocyte development was largely determined by its ability to regulate expression of SOX9, the master chondrogenic regulator, in cell culture studies12. A concerted action of ESRRa together with PGC1a for SOX9 expression in osteoarthritic (OA) chondrocytes also supports the positive involvement of ESRRa in chondrocyte development13. However, more direct evidence using an animal model is necessary to demonstrate the in vivo role of ESRRa in chondrocyte development.

In this report, we used the zebrafish model to examine the role of esrra in cartilage development during vertebrate embryogenesis. Expression of esrra is colocalised with genes necessary for cartilage development in pharyngeal arches during zebrafish embryogenesis. Knockdown of esrra induces abnormally formed cartilage structure in pharyngeal arches. Importantly, we found conserved ESRRa binding elements in the upstream regions of sox9 to which ESRRa can directly bind. Accordingly, sox9 overexpression partially rescues defective formation of cartilage induced by knockdown of esrra. These results establish ESRRa as a critical regulator of sox9 required for cartilage development in vivo.

Results

Differential activities of Esrra are required for different developmental programs during zebrafish embryogenesis

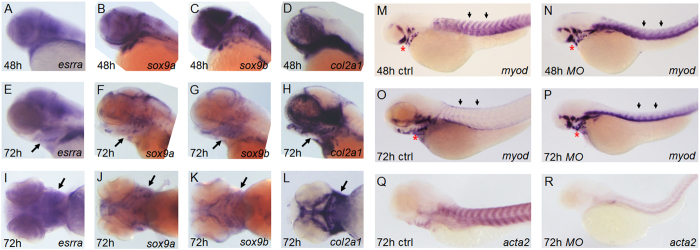

Initially, we examined expression of esrra during zebrafish embryogenesis by performing in situ hybridization. The transcript initially appears very weakly at 2 hours post fertilization (hpf) and becomes abundant in the posterior region at 10 hpf. Later during development, esrra is expressed in various tissues including brain, somites and pronephric duct primordium (Supplementary Fig. 1A–G). The esrra expression pattern is consistent with that reported in The Zebrafish Model organism Database (www.zfin.org). To determine whether esrra is expressed in cartilaginous elements, we compared its expression with that of sox9a/b and col2a1 in developing pharyngeal arches. Expression of esrra overlaps with that of sox9a/b and col2a1 at both 48 hpf (Fig. 1A–D) and 72 hpf (Fig. 1E–L) when cartilaginous cells are differentiate. This result suggests a potential role for esrra in cartilage development in zebrafish. However, a previous knockdown study in zebrafish showed severe gastrulation defects associated with regulatory roles of esrra in morphogenetic movement, which precluded further analysis for the role of esrra in animal development14. Since a gene may not contribute equally to the development of different cell types, we tested whether esrra is the case for different developmental programs. Indeed, we found that the degree of esrra knockdown matches the phenotypic severity of resulting embryos. For example, morpholinos (MOs that interfere with either transcription or splicing of esrra) at a lower dose induce a smaller head, shorter body length and curved body axis while MOs at a higher dose mimic the gastrulation defect phenotype that was reported previously (Supplementary Fig. 1H–K). Notably, we found that knockdown of esrra at a low dose induces defective muscle differentiation, a well-known effect of esrra deficiency. In particular, expression of myod in somites is decreased at 3 days post fertilization (dpf) in control embryos while retained in 80% (70/88) of esrra knockdown embryos (Fig. 1M–P). In addition, we find the expression of another muscle marker gene, acta2, being significantly reduced at 3 dpf in 81% (52/64) of esrra knockdown embryos (Fig. 1Q,R). These results suggest that esrra is required for various developmental programs during zebrafish embryogenesis and that it may exert its role with differential activities.

Figure 1. esrra is expressed in cartilaginous regions during zebrafish embryogenesis.

(A–L) Embryos at the indicated stages were subjected to in situ hybridization to analyse expression of esrra, sox9a, sox9b and col2a1. Arrows in (E–L) indicate pharyngeal arches where cartilage development occurs. Note that expression of esrra is largely overlapping with that of sox9a, sox9b and col2a1. (M–R) Embryos were injected with either MOctrl or MOesrra, raised to 48 hpf or 72 hpf as indicated, and analysed by in situ hybridization for expression of myod and acta2. myod expression in somites (arrows) is drastically decreased as muscle becomes differentiated from 48 hpf to 72 hpf in control embryos (compare M and O), while it sustains in MOesrra-injected embryos (compare N with P). In contrast, robust expression of acta2, a differentiated muscle marker, in control embryos is almost lost in MOesrra-injected embryos (compare Q with R). In addition, expression of myod in the pharyngeal arches (red asterisks) does not change from 48 hpf to 72 hpf in MOesrra-injected embryos, while myod in control embryo is expressed in a different subset of cells at 72 hpf as compared to that in 48 hpf. Embryos are shown in lateral views with anterior to the left except I–L where embryos are shown in ventral views.

Knockdown of esrra impairs cartilage development in pharyngeal arches

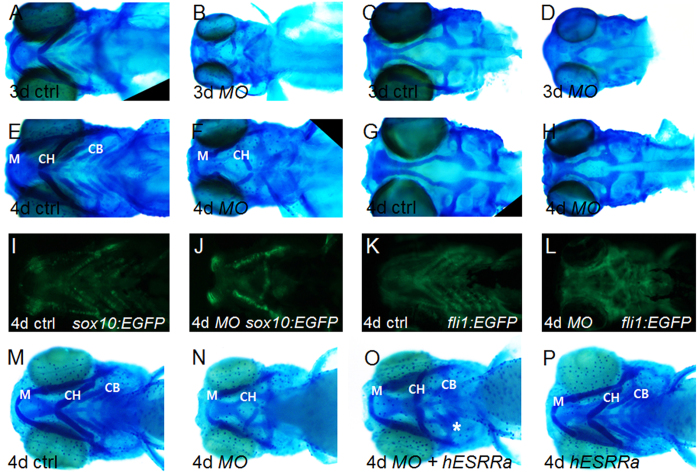

With the phenotypic severity corresponding to the degree of esrra knockdown, we focused on the role of esrra in cartilage development using a low-dose of MOesrra. Of note, esrra knockdown does not induce significant changes in the expression of other esrr members such as esrrb and esrrg (Supplementary Fig. 1L). Alcian blue staining showed that esrra knockdown induces 82% (76/93) of embryos displaying abnormal structure of cartilaginous elements in pharyngeal arches, including a smaller meckels’ arch, reversely-oriented ceratohyal and almost absent ceratobranchial cartilages, as compared to those in control (Fig. 2A,B,E,F). In contrast, the patterning of dorsal neurocranium including ethimoid plate and anterior basicranial commisures is relatively normal in MOesrra embryos albeit significantly smaller (Fig. 2C,D,G,H). The defective cartilaginous structure is further verified in two transgenic zebrafish lines, fli1:EGFP and sox10:EGFP (Fig. 2I–L), by which pharyngeal cartilages can easily be visualised. To confirm that the observed defects in cartilage are specific to esrra knockdown, we generated a full-length human ESRRa construct and performed a rescue experiment. Since overexpression of ESRRa by itself can induce developmentally defective embryos14, we used a concentration of ESRRa mRNA at which morphological abnormalities can minimally be observed. By examining dosage-dependent phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 2), we found that ESRRa mRNA at 100 pg partly rescues the cartilage defect induced by esrra knockdown. In particular, MOesrra alone induces 84% (42/50) of embryos having abnormal or missing cartilages, while 68% (54/80) of embryos injected with MOesrra together with human ESRRa mRNA show ceratobranchial cartilages albeit underdeveloped (Fig. 2M–P). These results indicate that esrra is indeed required for cartilage development during vertebrate embryogenesis.

Figure 2. The structure of craniofacial cartilage is disorganised upon knockdown of esrra.

(A–H) Embryos were injected with either MOctrl or MOesrra and subject to alcian blue staining at 3- or 4 dpf as indicated. Craniofacial cartilage, especially ceratohyal (CH) and ceratobranchial (CB) cartilage, are abnormally developed in MOesrra-injected embryos when compared to control embryos. Note that the structure of neural cranium is well organised although smaller in size in MOesrra-injected embryos (compare C and G with D and H). (I–K) sox10:GPF (I,J) or fli1:GFP (K,L) transgenic embryos were used to confirm the cartilage defects upon knockdown of MOesrra. (M–P) Human ESRRa mRNA (hESRRa) was co-injected with MOesrra into 1-cell stage of embryos which were subject to alcian blue staining. Embryos co-injected with hESRRa and MOesrra show partial restoration of CB (asterisk in O) and repress disorientation of CH induced by MOesrra alone (compare O with N). Misexpression of hESRRa at 100 pg does not impair cartilage development (P, see the text for detail). Embryos are shown in ventral view with anterior to the left.

Knockdown of esrra affects development of cranial neural crests that forms pharyngeal arches

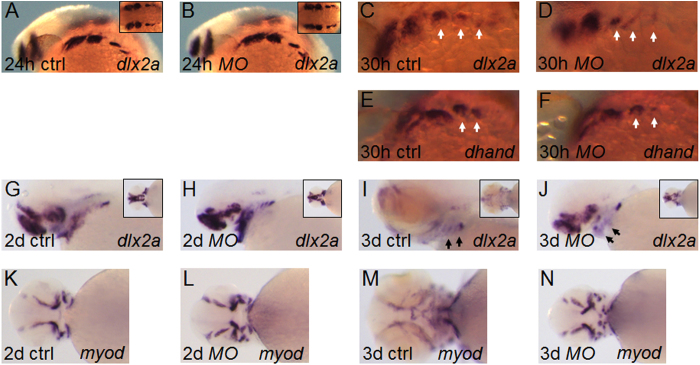

Our results suggested that esrra knockdown may interfere with specification and/or migration of neural crests that contribute to cartilage elements in pharyngeal arches. We examined dlx2a whose expression is found in both premigratory and postmigratory neural crests11. Knockdown of esrra does not affect dlx2a expression at 24 hpf in 100% (63/63) embryos, but slightly reduces it in branchial arches at 30 hpf in 82% (46/56) embryos (Fig. 3A–D). Expression of dhand is consistent with that of dlx2a at 30 hpf at which it is expressed at a level comparable to control in 1st and 2nd pharyngeal arches but at a slightly reduced level in branchial arches in 84% (37/42) of MOesrra-injected embryos (Fig. 3E,F). The strong expression of dlx2a in the pharyngeal cartilage in control embryos at 2 dpf, seems to be significantly decreased at 3 dpf when head regions including pharyngeal arches undergo substantial expansion (Fig. 3G,I). In sharp contrast, 80% (45/56) of MOesrra-injected embryos continue to express dlx2a strongly in the pharyngeal cartilage at 3 dpf in a pattern similar to that found at 2 dpf (compare Fig. 3H–J). Interestingly, myod expression in muscular structure of pharyngeal arches in MOesrra-injected embryos is reminiscent of dlx2a expression. In particular, we find a drastic change in myod expression from 2 dpf to 3 dpf in control embryos, while myod expression in 80% (70/88) of MOesrra-injected embryos at 3 dpf seems to be strikingly similar to that at 2 dpf (Fig. 3K–N). These results suggest that knockdown of esrra has a minor role in the specification of cranial neural crests but interferes with growth, maintenance and differentiation of pharyngeal cartilage and other components of pharyngeal arches such as muscles.

Figure 3. ESRRa regulates development of neural crest cells for cartilage development.

(A–J) Embryos at 1-cell stage were injected with either MOctrl or MOesrra and analysed for expression of dlx2a or dhand by in situ hybridization. Expression of dlx2a at 24 hpf shows a similar pattern between control and MOesrra-injected embryos while expression of both dlx2a and dhand at 30 hpf shows a slight decrease in the branchial arches (white arrows in D and F) in MOesrra-injected embryos. From 2 dpf to 3 dpf, expression of dlx2a becomes largely restricted to pharyngeal cartilage in control embryos (arrows in I), while it is significantly disorganised in the pharyngeal arches of MOesrra-injected embryos (arrow in J). (K–N) Expression of myod from 2 dpf to 3 dpf shows a significant change as the pharyngeal regions in control embryos undergo growth and differentiation (compare K to M). However, expression of myod at 3 dpf remains strikingly similar to that at 2 dpf (compare L and N), except few additional elements being developed in MOesrra-injected embryos. Embryos are shown in either lateral (A–J) or ventral views (K–N).

Esrra regulates expression of genes involved in cartilage development

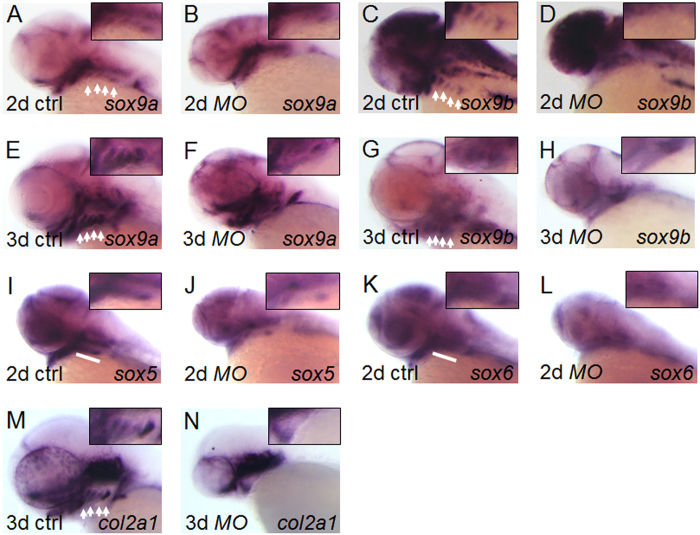

To further test the role of esrra in cartilage development, we examined the expression of genes critical for cartilaginous structures in pharyngeal arches. In zebrafish, there are two copies of sox9 genes, sox9a and sox9b, both of which cooperate to induce cartilage development15. We find that expression of sox9a seems to be slightly downregulated in pharyngeal arches as well as in the cranium and somites in 81% (58/72) of MOesrra-injected embryos at 1 dpf (Supplementary Fig. 3A,B), although it shows a similar level in the hindbrain at 2 dpf as compared to control embryos. Notably, upon esrra knockdown, sox9a expression in branchial arches is almost missing or severely decreased at 2 dpf and later in 83% (126/152) of MOesrra-injected embryos (Fig. 4A,B,E,F). The reduced expression of sox9a in branchial arches correlates well with the loss of cartilaginous elements as shown in Fig. 2. We find that sox9b expression is not affected at 1 dpf but is reduced in pharyngeal arches from 2- to 3 dpf in 81% (110/135) of MOesrra-injected embryos (Supplementary Fig. 3C,D, and Fig. 4C,D,G,H). This is consistent with a previous report in which expression of sox9b in pharyngeal arches only initiates slightly earlier than 48 hpf15.

Figure 4. ESRRa regulates expression of genes essential for cartilage development.

(A–N) Embryos at 1-cell stage were injected with either MOctrl or MOesrra, raised and analysed at the indicated stages for expression of sox9a, sox9b,sox5, sox6 and col2a1 by in situ hybridization. At 2- and 3 dpf, expression of sox9 (A–H) and col2a1 (M and N) is specifically decreased in the branchial arches in MOesrra-injected embryos, although it remains comparable in other expression domains as compared to that in control. Expression of sox5 and sox6 at 2 dpf is also substantially decreased in MOesrra-injected embryos as compared to that in control (I–L). White arrows or bars indicate branchial arches and insets shown are magnified views of the branchial regions.

Perturbed expression of sox9a/b in pharyngeal arches suggests that chondrocyte differentiation may also be impaired. To examine whether esrra regulates chondrocyte differentiation, we examined the expression of sox5 and sox6 implicated in chondrogenesis in mammals16. Although the role of sox5 and sox6 are not clearly demonstrated in zebrafish chondrogenesis, we found that 78% (49/63) and 79% (53/67) of MOesrra-injected embryos show significantly downregulated expression of sox5 and sox6, respectively, especially in the branchial arches (Fig. 4I–L). In addition, expression of col2a1 which encodes a major cartilage matrix component is also severely affected in the pharyngeal arches at 3 dpf in approximately 79% (44/56) of embryos upon knockdown of esrra (Fig. 4M,N). These results are consistent with sox5, sox6 and col2a1 being downstream of sox9 whose expression is perturbed upon esrra knockdown in this study. Furthermore, we also observed expression of other genes important for chondrocyte differentiation and maturation. In zebrafish, runx2b, one of the two paralogs of mammalian runx2, plays a critical role and regulates col10a1 expression in both chondrocyte and osteoblast lineages17,18. We found that both runx2b and col10a1 are significantly reduced upon esrra knockdown. In particular, runx2b expression in the parasphenoid, ceratobranchials and cleithrum is severely impaired and col10a1 expression in similar regions is also reduced in 81% (52/64) and 83% (65/78) of embryos, respectively, upon esrra knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 3E–H). This result is consistent with a previous report where Sox9b acts upstream of runx2b in chondrocyte differentiation and maturation17. These results indicate that esrra regulates expression of sox9a/b and the downstream genes necessary for cartilage development during zebrafish embryogenesis.

Esrra regulates survival of cartilaginous cells

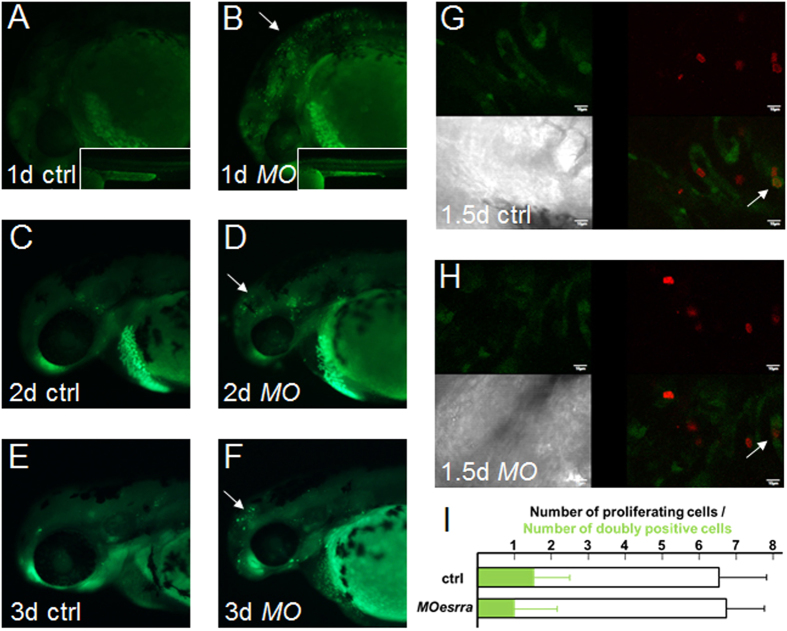

Defective formation of pharyngeal cartilage upon knockdown of esrra suggests that cell survival or proliferation of chondrocytes may be dependent on esrra activity. Upon knockdown of esrra, we find 83% (33/40) embryos displaying an increased number of apoptotic cells in the central nervous system at 1 dpf by acridine orange staining (Fig. 5A,B). In addition, the number of apoptotic cells is also slightly increased at 2- and 3 dpf in 81% (52/64) of esrra-knockdown embryos as compared to that in control (Fig. 5C–F), suggesting a repressive role for Esrra in apoptosis. This result may be consistent with a regulatory role for Esrra in the expression of sox9 which was shown to suppress apoptosis in mammals16.

Figure 5. ESRRa regulates survival but not proliferation of cartilaginous cells.

(A–F) 1-cell stage of embryos were injected with either MOctrl or MOesrra, raised and subjected to acridine orange stain to determine apoptotic cells at the stages indicated. Moesrra-injected embryos display a significant number of apoptotic cells in the head (arrows) and body trunk (insets) at the all observed stages as compared to controls. A combination of MOesrra and MOp53 does not suppress cell apoptosis. (G,H) sox10:GFP embryos were injected similarly to A–F, raised to the indicated stages, and processed to determine proliferation of cartilaginous cells by phosphorylated histone H3 immunostaining (pH3, red signal) in pharyngeal regions. White arrows indicate proliferating chondrogenic cells marked by both green and red. Scale bar is 10μm. (I) The total number of proliferating cells in the pharyngeal arches is similar between control and MOesrra-injected embryos (6.5+/−1.3 vs. 6.8+/−1.0 cells in average, respectively; n = 27). Also, the number of proliferating cartilaginous cells (doubly positive for both green and red) is also similar between control and MOesrra-injected embryos (1.5+/−1.0 vs. 1.0+/−1.2 cell in average, respectively; n = 27).

To examine whether knockdown of esrra impairs proliferation of pharyngeal chondrocytes, we performed immunostaining using phospho-histone H3 (pH3) antibody that detects nuclei of mitotic cells. We find that comparable numbers of pH3-positive mitotic cells in pharyngeal arches are observed in esrra-knockdown embryos as compared to that in control at 36 hpf, 2- and 3 dpf (n > 35 for each stage, Supplementary Fig. 4). To detect proliferating cartilaginous cells more specifically, we utilised sox10:EGFP transgenic zebrafish to analyse sox10-driven GFP-positive cartilaginous cells that are also pH3-positive. Consistent with Esrra being required for full development of cartilaginous elements in the pharyngeal arches, we find a decreased expression of sox10-derived GFP in 79% (62/78) of embryos injected with MOesrra. Among the embryos at 1.5 dpf with the reduced GFP expression upon esrra knockdown, 82% (27/33) of them have the number of proliferating cartilaginous cells (doubly positive for both GFP and pH3) with the range between 0 and 2 at 1.5 dpf (Fig. 5G–I). Control embryos also contain similar numbers of proliferating cartilaginous cells with average of 1.5, indicating no statistical significance between control and MOesrra-injected embryos. These results suggest that Esrra may play a minor role in proliferation but is necessary for survival of cartilaginous cells in the pharyngeal arches.

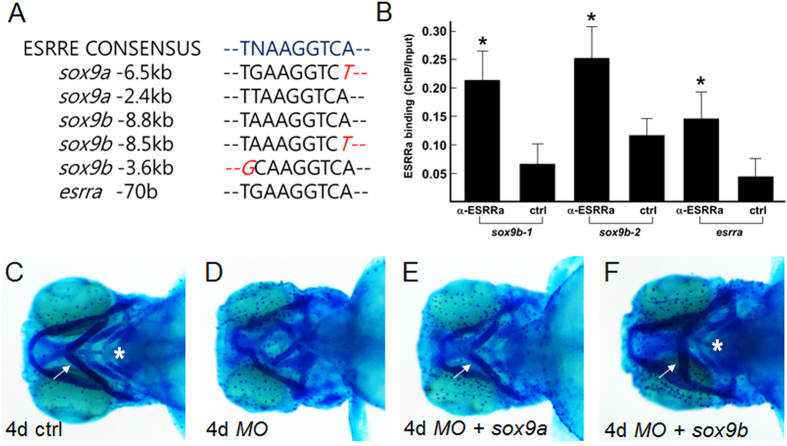

Esrra regulates expression of sox9 whose upstream regions contain putative ESRRa binding elements

ESRRa is known to bind a conserved binding sequence and hence regulates the expression of target genes. We found several putative binding elements for ESRRa in the upstream regions of sox9a and sox9b, and also an element in the proximal promoter of esrra itself (Fig. 6A). We tested the possibility that Esrra directly regulates sox9a and sox9b in zebrafish since esrra knockdown decreases expression of both as shown in Fig. 4. To examine the direct association of Esrra to these sites, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assay using zebrafish embryos injected with human ESRRa mRNA. As shown in Fig. 6B, ESRRa is reliably recruited to two potential ESRRa binding sequences located upstream of sox9b. In addition, we also find direct association of ESRRa to a putative binding site located within the proximal promoter of esrra gene itself (Fig. 6B). In support of this result, an in vivo reporter assay shows robust GFP expression driven by endogenous Esrra to the putative ESRRa binding element located upstream of sox9b (−3.6 kb), while a control vector containing only Carp beta-actin minimal promoter and GFP cDNA results in few GFP-positive cells (Supplementary Fig. 5). Importantly, coinjection of the ESRRa binding element of sox9b together with MOesrra significantly reduces the number of GFP-expressing cells, strongly suggesting that Esrra may directly regulate sox9b expression in vivo.

Figure 6. ESRRa directly binds ESRRE consensus elements located upstream of sox9b.

(A) Consensus DNA sequences to where ESRRa is known to bind (ESRRE consensus) are identified upstream of both sox9a and sox9b. In addition, esrra also contains an ESRRE consensus in the proximal promoter region (esrra −70 b). (B) Embryos at 1-cell stage were injected with hESRRa mRNA, raised and collected at 36 hpf for chromatin immunoprecipitation using anti-ESRRa antibody. Significant binding of hESRRa is detected at the ESRRE consensus sites located upstream of sox9b (−8.8~−8.5 kb denoted as sox9b-1and −3.6 kb as sox9b-2), but not detected at the site found upstream of sox9a (−6.5 kb). hESRRa also binds to the proximal promoter of esrra itself. Statistical analysis of pair-wise samples was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software. Values with p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant (indicated by asterisks). (C–F) Embryos were injected with MOesrra together with sox9a or sox9b mRNA, and subject to alcian blue staining at 4 dpf. White arrows indicate correctly-oriented ceratohyal cartilage, and white asterisks point to ceratobranchial arches. Note that overexpression of sox9b efficiently rescues defective cartilage induced by esrra knockdown, while overexpression of sox9a only partially rescues proper formation of ceratohyal cartilage.

Since Esrra may directly regulate expression of sox9 as well as esrra itself, we reasoned that sox9a/b overexpression may rescue defective cartilage induced by esrra knockdown if Esrra acts through Sox9. To examine whether sox9 overexpression can rescue defective cartilage in esrra-knockdown embryos, we cloned full length cDNAs of sox9a and sox9b. Since sox9 overexpression was reported to induce developmental defects due presumably to ectopic upregulation of target genes19, we first determined a concentration of sox9 at which general development is minimally affected but cartilage development can be rescued in combination of MOesrra (Supplemental Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 6C–F, microinjection of MOesrra together with either sox9a or sox9b mRNA into 1 cell stage of zebrafish embryos can rescue at least in part the defective formation of cartilaginous structures indicating that Esrra indeed regulates expression of sox9 for cartilage development in zebrafish. These results indicate that Esrra directly regulates sox9b and esrra itself for cartilage development in zebrafish.

Discussion

A role for ESRRa in chondrogenesis is largely supported by a previous study in which ESRRa was shown to regulate SOX9 expression in vitro12. In this study, we show that esrra and sox9a/sox9b/col2a1 are co-expressed in developing chondrocytes during zebrafish embryogenesis which potentiates a role for Esrra in chondrogenesis in vivo (Fig. 1). Previously, disruption of esrra expression in zebrafish was reported to induce defective gastrulation due to abnormal morphogenetic cell movement14, which precluded further analysis for the role of esrra in animal development. We re-evaluated the roles of esrra in animal development during zebrafish embryogenesis by a morpholino-based knockdown approach. Consistent with a previous report, we find that near-complete blockage of esrra expression induces gastrulation defect. However, we also find that a less-complete knockdown of esrra induces embryos with smaller head, defective muscle and abnormal cartilage. The target site of our translation-blocking MO overlaps with that in the previous report, and we do not completely understand the phenotypic variance between the previous report and our study. However, the difference could at least in part be due to a threshold effect resulting from the differential degree of gene knockdown as suggested previously9. Consistent with this hypothesis, the observed phenotypes in the cartilage as well as muscles can be detected by injecting low dose of MO, while we find a significant developmental delay upon injection of high dose of MO. Therefore, differential activities of Esrra may be involved in the patterning of different tissues by which muscles and cartilage may require full activities of Esrra while migrating cells during gastrulation only require basal activities. In view of this scenario, other members of Esrrs that are expressed during embryogenesis4 may not compensate for a more-complete loss of esrra that leads to gastrulation defects. In support of this, we found that esrra knockdown does not induce changes in expression levels of esrrb and esrrg. We note that our phenotypic analysis may represent a mild version of esrra knockdown since we chose a MO concentration that does not interfere with gastrulation but cartilage formation.

The mechanism by which Esrra acts in chondrocyte development including cell death, proliferation and differentiation, may depend on transcriptional activation of sox9b. First, ChIP analysis reveals an association of human ESRRa to two putative ESRRa binding sequences located upstream of sox9b, implicating that ESRRa may directly regulate sox9b expression. This finding is further supported by an in vivo reporter assay by which we show that endogenous Esrra can drive GFP expression by presumably binding to one of the sox9b ESRRa binding elements introduced in a reporter vector. Second, we find decreased expression of sox9b in response to esrra knockdown, while we do not detect an association of ESRRa in a seemingly well-conserved ESRRa binding sequence located upstream of sox9a. Since the presence of a positive regulatory loop between sox9a and sox9b in developing zebrafish has previously been reported19, decreased expression of sox9b may in turn influence sox9a expression in the cartilage regions. Indeed, we observe a reduced expression of sox9a in pharyngeal arches upon esrra knockdown. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that ESRRa association to sox9a gene may be restricted to a small subset of chondrogenic cells, which causes the binding signal to fall below the detection level due to the heterogeneous nature of samples used for ChIP analysis. Third, phenotypes induced by either a sox9b mutation or knockdown in zebrafish in previous reports are remarkably similar to those observed in this study upon esrra knockdown19,20. In particular, the observation of embryos with increased cell death and defective cell differentiation upon disruption of either esrra or sox9b indicates a functional ESRRa-Sox9 axis for supporting a complete set of crest-driven chondrocyte development in pharyngeal arches. Fourth, ectopic expression of sox9 rescues at least partially MOesrra-induced defects in cartilage development. These findings strongly suggest that ESRRa acts through Sox9 activity during cartilage development.

We find a significant sequence homology between mammalian and zebrafish ESRRa, which in turn suggests functional homology between human and zebrafish. We observe that knockdown of esrra induces defective muscle development, a well-known phenotype associated ESRRa deficiency in mice. In addition, we show that MOesrra-induced phenotype can partially be rescued by ectopic expression of human ESRRa. Recently, ESRRa reportedly cooperates with other partner proteins, such as PGC1a/b, HIF1-a and mTOR, in regulating cellular metabolism and hence animal development. Therefore, it will be interesting to understand how ESRRa contributes its function during animal development, a sophisticated process that orchestrates diverse cellular programs into a coordinated series of events necessary for achieving proper animal body plan and function. In summary, we report for the first time a direct involvement of ESRRa in cartilage development in vivo achieved at least in part by regulating expression of sox9, an essential component of chondrogenesis.

Methods

Animal care and transgenic zebrafish

The zebrafish and their embryos were handled and staged according to standard protocols21. All experimental protocol was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Animal Experiments of the Wonkwang University (WKU15-102) and carried out under the Guidelines for Animal Experiments.

Constructs and mRNA or morpholino (MO) microinjection

Human ESRRa construct was cloned into pCS2+ after digesting out the open reading frame of ESRRa from a construct purchased from Addgene, USA. Zebrafish full length sox9a and sox9b cDNA were cloned into pCS2+ and used for mRNA synthesis after linearization. Constructs for making probes for in situ hybridization were cloned into Topo vector (esrra, col2a1, acta2, sox5, sox6, col10a1, sox9a and sox9b) or reported previously (dlx2a, dhand and myod). mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, USA) was used to synthesize mRNA and 100 pg of mRNA was injected for the rescue experiments. Morpholinos (MOs) were purchased from Gene Tools, OR, USA. 3 ng of MO was used to examine cartilage defects and 10 ng MO was used to confirm gastrulation defects. MO sequences are: 5′-CGTCGTTCTCTGGAAGACATGATAC-3′ (translation-blocking MO) and 5′-ATTGCCTGTTGGATGAAGGGAAACC-3′ (splicing-blocking MO), and 5′- AACATACATCAGTTTAATATATGTA-3′ (control MO). A construct for GFP reporter assay in vivo was initially generated by cloning 282 base pairs including a putative ESRRa binding sequence at the upstream of sox9b (primers used: F-5′CCTGACCATTACTCAGCGGATGGAGTAT3′ and R- 5′CATCCATGCTCAACTAACCCTCAGCA3′) into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, USA) in which a DNA fragment encompassing Carp beta-actin minimal promoter and GFP cDNA was subsequently inserted downstream of the ESRRa binding element. All clones were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. 50 pg of either control construct or GFP reporter alone or in combination with MOesrra was injected into 1-cell stage of zebrafish embryos, and live images at various developmental stages were taken using a Leica M165FC microscope equipped with Leica DFC500.

In situ hybridization, immunostaining, acridine orange staining and alcian blue staining

In situ hybridization and immunostaining were performed as previously described22. Phosphorylated histone H3 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., USA. For acridine orange staining, embryos were manually dechorionated and incubated in acridine orange (0.5μl of 4% acridine orange (Sigma, USA) in 10 ml egg water) for 1 hour at room temperature. Embryos were washed thrice with egg water and then observed using a fluorescence microscope (Leika M165FC). Alcian blue staining was performed as described previously18. Briefly, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and maintained in 100% MeOH at −20 °C until use. Embryos were washed several times in PBST (Phosphate buffered saline with 0.1% tween) and bleached in 30% hydrogen peroxide by exposing to bright light for 2 hours. Embryos were rinsed twice with PBST, transferred into alcian blue solution (1% concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), 70% ethanol, 0.1% alcian blue (Sigma, USA) and stained overnight. Embryos were washed three times with acidic ethanol (5% concentrated HCl, 70% ethanol) and twice with PBST. Embryos were photographed using Leica M165FC microscope equipped with Leica DFC500 or Olympus IX81, a confocal microscope.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and western blot

To determine MO efficiency, total RNA was prepared from 10 embryos at 1 dpf using Trizol (Ambion, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. First strand cDNA was synthesised (Roche, USA) and quantitative PCR was performed. Primer sequences used are F-5′ACTGGTAGTGGAGGAGGGC3′ and R-5′CTCTTGTTGTACTTCTGTCGTC3′. RT-PCR analysis for esrrb and esrrg was performed using the following primers: F-5′ ATCGGGATACCACTATGGTGTGGCCT3′ and R-5′ GTGAGCCCCAGGTAAGCTGTGTTTT3′ (esrrb) and F-5′ AATACGACATCGAGGCCAGTCACATG3′ and R-5′ ATAGTGGTAACCAGAAGCGATGTCCCC3′ (esrrg). Western blot analysis was performed as previously described23. Anti-ESRRa or -b-actin antibodies were used to specifically detect hESRRa (including endogenous zebrafish Esrra) or b-actin, respectively, after running a gel with embryo lysates equivalent to 10 embryos per lane.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously22 with following modifications. In brief, embryos injected with human ESRRa mRNA and raised to 36 hpf were dissociated into single cells and crosslinked in 1% formamide solution. Samples were sonicated with 35% amp for a total of 2 minutes using Epishear Probe Sonicator (Active Motif, USA) and then pre-cleared using 80 μl of protein A agarose slurry containing salmon sperm DNA (Merck Millipore Corp., USA) for 1 hour at 4 °C. Samples were spun and supernatants were divided equally into 2, each labelled as an antibody or a control. 40 ul of protein A agarose slurry was added to both samples and 1 μg anti-ESRRa antibody (Abcam, USA) was added only to the samples labelled as antibody. All the remaining steps were followed as described. Primer sequences for quantitative PCR are: esrra (F-5′AAACACCACCTCACCTGCACATATTG3′, and R-5′GTCAGAGCGTCGTT CTCTGGAAG3′), sox9b-1 (F-5′GTGTGAGATCAGAGTTAATAAAGGTCA3′ and R-5′CCCAGCCAATCACAGTCAGTTAGCA3′), sox9b-2 (F-5′ CTCCACACAGAAACACCAACTGACCC3′ and R-5′ TACGTGCAGAGTGGCGGCACGGT3′). Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software (International Business Machines Corp., USA). Values with p < 0.05 (indicated by asterisks) were considered to be statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kim, Y.-I. et al. Cartilage development requires the function of Estrogen-related receptor alpha that directly regulates sox9 expression in zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 5, 18011; doi: 10.1038/srep18011 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Drs. S-K Choe and R Park laboratories for sharing materials and comments to this project. We also thank Dr. Hyunju Ro for providing a vector containing Carp beta actin minimal promoter and GFP. This work was supported by grants NRF-2011-0030130, NRF-2013R1A1A2010518 and NRF-2014M3A9D8034463.

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.-K.C. and R.P. designed the experiments. Y.-I.K., J.N.L., S.B., I.-K.N., K.-W.Y. and S.-K.C. performed experiments. J.N.L., S.-J.K., G.-S.O., H.-J.K., H.-S.S., S.-K.C. and R.P. analysed data. Y.-I.K., S.-K.C. and R.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Giguere V., Yang N., Segui P. & Evans R. M. Identification of a new class of steroid hormone receptors. Nature 331, 91–94 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H., Yang L. & Stallcup M. R. Hormone-independent transcriptional activation and coactivator binding by novel orphan nuclear receptor ERR3. The Journal of biological chemistry 274, 22618–22626 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacker J. M., Pettersson K., Gustafsson J. A. & Laudet V. Transcriptional targets shared by estrogen receptor-related receptors (ERRs) and estrogen receptor (ER) alpha, but not by ER beta. Embo J 18, 4270–4279 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand S. et al. Unexpected novel relational links uncovered by extensive developmental profiling of nuclear receptor expression. Plos Genet 3, 2085–2100 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audet-Walsh E. & Giguere V. The multiple universes of estrogen-related receptor alpha and gamma in metabolic control and related diseases. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 36, 51–61 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpulla R. C. Metabolic control of mitochondrial biogenesis through the PGC-1 family regulatory network. Bba-Mol Cell Res 1813, 1269–1278 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaveroux C. et al. Molecular and Genetic Crosstalks between mTOR and ERR alpha Are Key Determinants of Rapamycin-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver. Cell Metab 17, 586–598 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou C. et al. ERR alpha augments HIF-1 signalling by directly interacting with HIF-1 alpha in normoxic and hypoxic prostate cancer cells. J Pathol 233, 61–73 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnelye E., Merdad L., Kung V. & Aubin J. E. The orphan nuclear estrogen receptor-related receptor alpha (ERR alpha) is expressed throughout osteoblast differentiation and regulates bone formation in vitro. J Cell Biol 153, 971–983 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnelye E. & Aubin J. E. An Energetic Orphan in an Endocrine Tissue: A Revised Perspective of the Function of Estrogen Receptor-Related Receptor Alpha in Bone and Cartilage. J Bone Miner Res 28, 225–233 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimenko M. A., Ekker M., Wegner J., Lin W. & Westerfield M. Combinatorial expression of three zebrafish genes related to distal-less: part of a homeobox gene code for the head. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 14, 3475–3486 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnelye E., Zirngibl R. A., Jurdic P. & Aubin J. E. The orphan nuclear estrogen receptor-related receptor-alpha regulates cartilage formation in vitro: Implication of Sox9. Endocrinology 148, 1195–1205 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnelye E., Reboul P., Duval N., Cardelli M. & Aubin J. E. Estrogen Receptor-Related Receptor alpha Regulation by Interleukin-1 beta in Prostaglandin E-2- and cAMP-Dependent Pathways in Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum-Us 63, 2374–2384 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardet P. L., Horard B., Laudet V. & Vanacker J. M. The ERR alpha orphan nuclear receptor controls morphogenetic movements during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev Biol 281, 102–111 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang E. F. et al. Two sox9 genes on duplicated zebrafish chromosomes: expression of similar transcription activators in distinct sites. Dev Biol 231, 149–163 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H., Chaboissier M. C., Martin J. F., Schedl A. & de Crombrugghe B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. J Bone Miner Res 17, S142–S142 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores M. V. et al. Duplicate zebrafish runx2 orthologues are expressed in developing skeletal elements. Gene expression patterns: GEP 4, 573–581, doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.01.016 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. I. et al. Establishment of a bone-specific col10a1:GFP transgenic zebrafish. Molecules and cells 36, 145–150 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y. L. et al. A pair of Sox: distinct and overlapping functions of zebrafish sox9 co-orthologs in craniofacial and pectoral fin development. Development 132, 1069–1083 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y. L. et al. A zebrafish sox9 gene required for cartilage morphogenesis. Development 129, 5065–5079 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B. & Schilling T. F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 203, 253–310 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S. K., Ladam F. & Sagerstrom C. G. TALE Factors Poise Promoters for Activation by Hox Proteins. Dev Cell 28, 203–211 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S. K., Vlachakis N. & Sagerstrom C. G. Meis family proteins are required for hindbrain development in the zebrafish. Development 129, 585–595 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.