Abstract

Background:

Overexpression of microRNA-31 (miR-31) is implicated in the pathogenesis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), a deadly disease associated with dietary zinc deficiency. Using a rat model that recapitulates features of human ESCC, the mechanism whereby Zn regulates miR-31 expression to promote ESCC is examined.

Methods:

To inhibit in vivo esophageal miR-31 overexpression in Zn-deficient rats (n = 12–20 per group), locked nucleic acid–modified anti-miR-31 oligonucleotides were administered over five weeks. miR-31 expression was determined by northern blotting, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and in situ hybridization. Physiological miR-31 targets were identified by microarray analysis and verified by luciferase reporter assay. Cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and expression of inflammation genes were determined by immunoblotting, caspase assays, and immunohistochemistry. The miR-31 promoter in Zn-deficient esophagus was identified by ChIP-seq using an antibody for histone mark H3K4me3. Data were analyzed with t test and analysis of variance. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results:

In vivo, anti-miR-31 reduced miR-31 overexpression (P = .002) and suppressed the esophageal preneoplasia in Zn-deficient rats. At the same time, the miR-31 target Stk40 was derepressed, thereby inhibiting the STK40-NF-κΒ–controlled inflammatory pathway, with resultant decreased cellular proliferation and activated apoptosis (caspase 3/7 activities, fold change = 10.7, P = .005). This same connection between miR-31 overexpression and STK40/NF-κΒ expression was also documented in human ESCC cell lines. In Zn-deficient esophagus, the miR-31 promoter region and NF-κΒ binding site were activated. Zn replenishment restored the regulation of this genomic region and a normal esophageal phenotype.

Conclusions:

The data define the in vivo signaling pathway underlying interaction of Zn deficiency and miR-31 overexpression in esophageal neoplasia and provide a mechanistic rationale for miR-31 as a therapeutic target for ESCC.

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is a major cause of cancer death worldwide (1). Because of lack of early symptoms, ESCC is typically diagnosed at an advanced stage, and only 10% of patients survive five years. Thus, clarification of the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of ESCC and development of new prevention and therapeutic strategies are urgently needed.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by means of translational inhibition and mRNA degradation (2). Each miRNA has the ability to inhibit multiple target genes or entire signaling pathways, regulating a range of biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. MiRNA expression levels are altered in all human cancers studied (3). MiRNAs can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors (4,5) and have emerged as therapeutic targets for cancer (6). The challenge is to identify their protein targets and determine how these protein targets contribute to tumor initiation and progression.

Risk factors for ESCC include alcohol and tobacco use and known nutritional factors such as Zn deficiency (7). Our well-characterized Zn-deficient (ZD) rat esophageal cancer model reproduces the ZD (7) and inflammation feature of human ESCC (8) and is exquisitely sensitive to esophageal tumorigenesis by environmental carcinogens (9,10). We have previously shown that rats on a ZD diet for five weeks develop hyperplastic esophagi with a distinct gene signature that includes upregulation of the proinflammation mediators S100a8/a9 (11). Prolonged ZD (23 weeks) leads to an expanded cancer-associated inflammatory program (10) and induction of an oncogenic miRNA signature with miR-31 as the top upregulated species (12), as also observed in human ESCCs (13,14).

miR-31 is among the most frequently dysregulated microRNAs in human cancers (15). Depending on tumor type, miR-31 can be up- or downregulated, thus exhibiting oncogenic or tumor suppressive roles in cancers. Notably, miR-31 is overexpressed and oncogenic in colorectal cancer (16), lung cancer (17), and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), including ESCC (13,14), tongue SCC (18), head and neck SCC (19), and skin SCC (20), but it is downregulated in serous ovarian cancer (21). The mechanisms by which miR-31 upregulation contributes to ESCC initiation and progression are not understood. In the present study, the biological functions of miR-31 in esophageal neoplasia and the mechanism whereby Zn regulates miR-31 expression to promote ESCC were examined.

Methods

Rat Studies

Animal protocols were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Animal Care and Use Committee. Weanling male Sprague-Dawley rats were from Taconic Laboratory. Custom-formulated ZD and Zn-sufficient (ZS) diets (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) were identical except for the amount of zinc, which was 3 to 4 ppm for ZD and 60 ppm for ZS diet. Further details on animal studies, tissue isolation, RNA preparation, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), TaqMan miRNA assay, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, western blot, northern blot, caspase, luciferase, cell proliferation, and electrophoretic mobility shift assays, in situ hybridization (ISH), immunohistochemistry, and serum Zn measurement are in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Locked-Nucleic Acid (LNA)–Modified Oligonucleotides

Custom unlabeled and phosphothioated LNATM anti-rno-miR-31 oligonucleotide (5’-CAGCTATGCCAGCATCTTGCCT-3’, complementary to nucleotides 1–22 in the mature miR-31 sequence) and control rno-miR-31 scrambled oligonucleotide (5’-GTGTAACACGTCTATACGCCCA-3’) were obtained from Exiqon (Vedbaek, Denmark).

Human ESCC Samples and Cell Lines

Twelve cases of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) human ESCC samples were obtained from Thomas Jefferson University Hospital (Philadelphia, PA). Human ESCC cell lines (KYSE-series) that were established from primary ESCC tumors (22) were purchased from German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures. Human esophagus Het-1A was from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) with 5% fetal bovine serum at 37oC with 5% CO2.

miRNA and mRNA Expression Profiling and Analysis

The Ohio State University custom miRNA microarray chips (OSU_CCC version 3.0) and Affymetrix Rat Genome 230 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix), respectively, were employed. See the Supplementary Methods (available online) for details. The ArrayExpress accession numbers for miRNA and mRNA expression profiling are E-MTAB-2208 and E-MTAB-2315, respectively.

ChIP Sequencing

The ChIP reaction was performed at Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA), as detailed in the Supplementary Methods (available online). Briefly, an aliquot of esophageal chromatin (30 μg) was precleared with protein A agarose beads (Invitrogen). DNA was immune-precipitated with anti-H3K4me1 (Active Motif, 39297, Lot. 1), anti-H3K4me3 (Active Motif, 39159 Lot. 4), or anti-H3K27me3 (Millipore 07-449, Lot. JBC1854858). ChIP sequencing at 50bp single end (approximately 40M reads/sample) was performed on Illumina HiSeq 2000 at HudsonAlpha Genomic Service Laboratory (Huntsville, AL).

Peak Calling and Data Analysis

Details are given in the Supplementary Methods (available online). Briefly, the collection of aligned reads were filtered to remove artifacts and mapped to the rat genome (rn4) using the Bowtie (23) algorithm. The number of uniquely mapped monoclonal reads for each ChIP-seq group is shown in Supplementary Table 4 (available online). To identify enriched regions of histone modifications ChIP-seq data, peak calling was performed using 0 algorithm (24).

MOTIF Finding and Quality Control

To find TFBs, we used rat genome (rn4) and Jaspar (25) and TRANSFAC database (26). Further details are given in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The Student’s t test was used to detect differences in comparisons involving only two groups. Data between the four subject groups were analyzed by analysis of variance. For some variables (caspase, NF-κΒ p65, and miR-31 levels), a logarithmic transformation was performed to minimize the effects of heteroscedasticity. Differences among the groups were assessed using the Tukey-HSD post hoc t test for multiple comparisons. Statistical tests were two-sided and were considered significant at P values of less than .05. Statistical analysis was performed using R (http://www.R-project.org).

Results

Establishment of a Rat Esophageal Neoplasia Model Overexpressing miR-31

Previously (12) we examined the effect of long-term ZD (23 weeks) on miRNA expression in eight rat tissues by nanoString miRNA profiling assay, and miR-31 overexpression was documented in esophagus and two other stratified squamous epithelial tissues (tongue and skin) and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. To establish an in vivo esophageal neoplasia model overexpressing miR-31 for examining conditions that lead to human ESCC initiation, we determined if short-term ZD (five weeks) that produces a hyperplastic esophageal phenotype with a proinflammation gene signature (11) induces miR-31 upregulation as does long-term ZD (12). For this, we performed an array-based miRNA expression profiling (27) of esophageal mucosa from weanling rats fed a ZD or ZS diet for five weeks (n = 4/dietary group). Fourteen dysregulated miRNAs were identified in ZD esophagus (q value < 10% [q value is the minimum false discovery rate {FDR} at which the test may be called significant]) (Supplementary Table 1, available online). Notably, miR-31 was the most upregulated species (ZD vs ZS = 10-fold upregulation, q value = 0%). This finding was verified by qPCR (Figure 1A) and northern analyses (Figure 1B), using RNA samples from ZD and ZS esophagus (n = 8 rats per group). Using the same RNA assessment methods, we found that five weeks after ZD rats were switched to a ZS diet, the ZD-induced miR-31 overexpression was returned to normal ZS level (Zn-replenished [ZR]/5wk rats) (Figure 1, A and B). Thus, miR-31 expression is responsive to Zn treatment, establishing a short-term ZD esophageal preneoplasia model for study of effects of miR-31 overexpression and silencing.

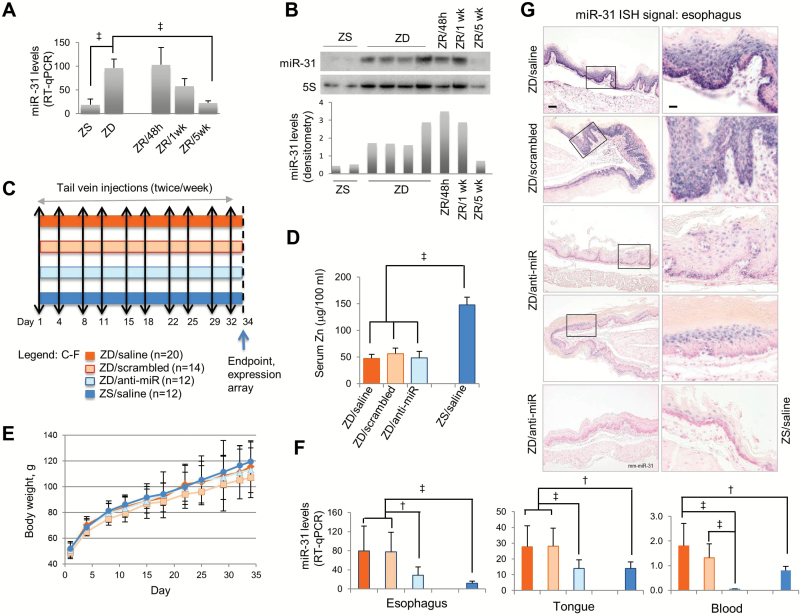

Figure 1.

Systemic delivery of locked nucleic acid–mediated anti-miR-31 in Zn-deficient (ZD) rat esophageal preneoplasia model. A) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis of esophageal miR-31 expression in Zn-modulated rats, using rat snoRNA as the normalizer (n = 8 rats/group, ‡P < .001, Tukey-HSD post hoc unpaired t test for multiple comparisons). Error bars represent standard deviation. B) Northern analysis of esophageal miR-31 expression in Zn-modulated rats (n = 5–8 rats/group). C-G) Systemic delivery of anti-miR-31 to ZD rats. C) Study design. D) Serum Zn levels are similar among ZD groups but statistically significantly lower than Zn-sufficient (ZS) rats (n = 12–20/group, ‡P < .001). Error bars represent standard deviation. E) Growth curves are similar in all four rat groups. Error bars represent standard deviation. F) qPCR analysis of miR-31 expression in esophagus, tongue, and blood in four rat groups, using rat snoRNA as the normalizer (n = 12–20 rats/group). Esophagus: ZD/saline vs ZS/saline (‡P < .001), ZD/scrambled vs ZS/saline (‡P < .001), ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline (†P = .004), and ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled (†P = .002). Tongue: ZD/saline vs ZS/saline (†P = .002), ZD/scrambled vs ZS/saline (†P = .001), ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline (‡P < .001), and ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled (‡P < .001). Blood: ZD/saline vs ZS/saline (†P = .009), ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline (‡P < .001), and ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled (‡P < .001). Error bars represent standard deviation. G) In situ hybridization (ISH) analysis shows moderate/infrequent miR-31 signal (blue, 4-nitro-blue tetrazolium and 5-brom-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate; counterstained by nuclear fast red) in ZD/anti-miR and ZS/saline esophagus, but strong/abundant miR-31 signal in hyperplastic ZD controls. No ISH signal was seen with mm-miR-31 (two mismatches). Scale bars: left = 100 μm; right = 25 μm. Open rectangles are insets shown in panels to the right. All statistical tests were two-sided. RT-qPCR = real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction; ZD = Zn-deficient; ZR = Zn-replenished; ZS = Zn-sufficient.

In Vivo Anti-miR-31 Delivery in Zn-Deficient Rat Esophageal Preneoplasia Model

LNA-modified oligonucleotides are a class of RNA that exhibits in vivo high biostability, low toxicity, and adequate biodistribution (28). LNA-anti-miR-122 oligos were shown to mediate effective in vivo inhibition of liver-expressed miR-122 function in rodents (29) and nonhuman primates (30). In a phase 2a clinical trial to treat patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, miravirsen (an LNA-modified inhibitor of miR-122) showed dose-dependent reductions in HCV RNA levels, thus demonstrating a therapeutic effect by targeting a host miRNA (31).

To inhibit esophageal miR-31 expression in vivo in Zn-deficient rats, we used LNA-anti-miR-31 oligonucleotide (complementary to nt 1–22 in the mature miR-31 sequence, hereafter called anti-miR). As depicted in Figure 1C, male weanling rats received a ZD or ZS diet and were randomized into four groups: ZD/anti-miR, ZD/LNA-scrambled, ZD/saline, and ZS/saline. The animals received 10 doses of anti-miR, scrambled oligos, or saline, over a period of five weeks. During the five-week study, the growth rate of all ZD groups was comparable with pair-fed ZS rats (Figure 1E). Regardless of treatment, serum Zn level in the three ZD groups was similar (~50 μg/100mL), but lower than in ZS rats (P < .001) (Figure 1D).

After five weeks of ZD diet, qPCR analysis (Figure 1F) showed that ZD controls had markedly higher miR-31 levels in esophagus, tongue, and circulating blood (P = .009 to < .001) than the ZS counterpart, a result consistent with long-term ZD (23 weeks) (12). Importantly, anti-miR-31 treatment resulted in approximately 60% inhibition of miR-31 expression in the three tissues vs counterpart ZD controls (esophagus: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled, P = .002; tongue: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled, P < .001; blood: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled, P < .001) (Figure 1F). The qPCR findings were confirmed at the cellular level by in situ detection of miR-31 in FFPE esophageal/lingual tissues. As shown in Figure 1G (esophagus) and Figure 2A (tongue), anti-miR-31 treatment resulted in an overall reduction in the scope and intensity of miR-31 signal in ZD/antimiR esophageal/lingual epithelia vs ZD controls (n = 10 rats/cohort). Thus, despite continued dietary Zn deficiency, anti-miR-31 delivery effectively inhibited ZD-induced miR-31 expression in the esophagus/tongue.

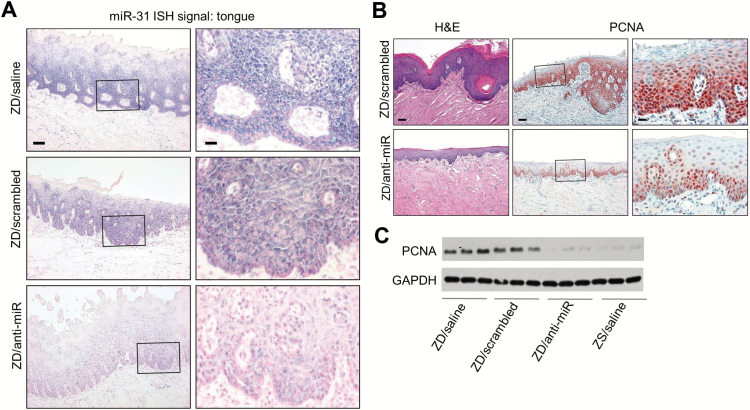

Figure 2.

Anti-miR-31 effects on Zn-deficient (ZD) rat lingual preneoplasia. A) In situ hybridization (ISH) analysis of miR-31 expression. miR-31 signal (blue, 4-nitro-blue tetrazolium and 5-brom-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate) is moderate/infrequent in ZD/anti-miR tongue, but strong/abundant in hyperplastic ZD controls. Scale bars: left = 100 μm; right = 25 μm. Open rectangles are insets shown in panels to the right. B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showing a thinned ZD/anti-miR lingual epithelium vs hyperplastic ZD control tongue; immunohistochemical showing few PCNA-positive nuclei (red, 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate-chromogen) in thinned ZD/anti-miR tongue vs abundant PCNA-positive nuclei in proliferative ZD/scrambled control (H&E, scale bar = 100 μm. PCNA, scale bars: right = 100 μm; left = 25 μm). Open rectangles are insets shown in panels to the right. C) Immunoblot analysis shows reduced PCNA expression in tongue following systemic delivery of anti-miR-31. H&E = hematoxylin and eosin; ISH = in situ hybridization; ZD = Zn-deficient.

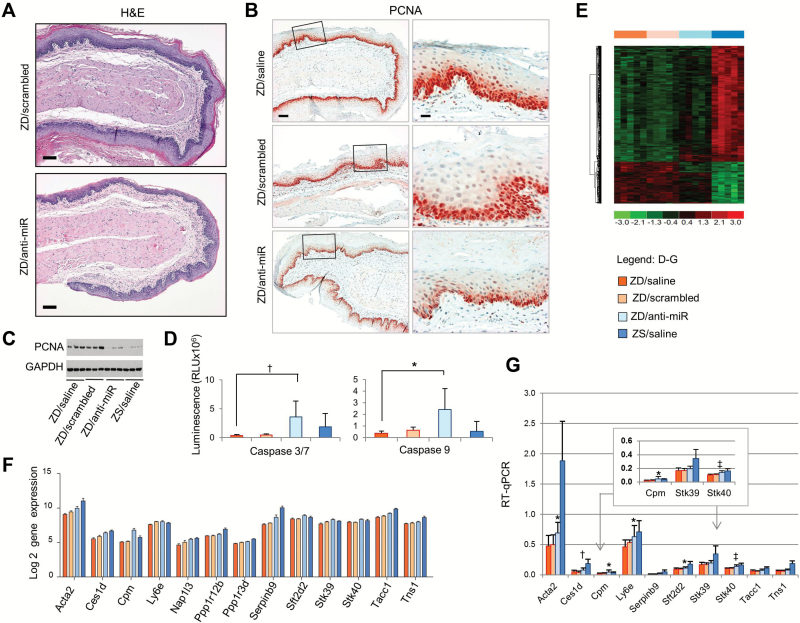

Macroscopically, anti-miR–treated ZD esophageal epithelia were strikingly less swollen than control ZD esophagi. Histologically, the ZD/anti-miR cohort showed a markedly thinned epithelium with fewer cell layers than the hyperplastic ZD/scrambled cohort (Figure 3A). These findings demonstrate that miR-31 inhibition prevented the development of a hyperplastic esophageal phenotype in rats in spite of their ZD diet.

Figure 3.

Anti-miR-31 effects on Zn-deficient (ZD) rat esophageal preneoplasia and potential miR-31 targets. A) Histology of ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled esophagus (hematoxylin and eosin stain, scale bar = 100 μm). B) Immunohistochemical analysis shows few PCNA-positive nuclei (red, 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate-chromogen) in thinned ZD/anti-miR esophagus vs abundant PCNA-positive nuclei in proliferative ZD controls (scale bars: left = 100 μm; right = 25 μm). Open rectangles are insets shown in panels to the right. C) Immunoblot analysis shows reduced PCNA expression in esophagus following systemic delivery of anti-miR-31. D) Luminescent assays show caspase 3/7 and caspase 9 activities in the four rat groups (n = 5–8 rats/group; caspase 3/7, †P = .005; caspase 9, *P = .019, Tukey-HSD post hoc t test). Error bars represent standard deviation. E) Unsupervised hierarchical cluster of the most important genes (upregulated genes, red; downregulated genes, green) in rat esophagi from the four rat groups (Figure 1C). F) Barplot graph showing expression of 13 predicted miR-31 targets in ZD esophagus that were derepressed after anti-miR treatment. G) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of the predicted genes, using OAZ1 as normalizer (n = 8–12 rats/group). Error bars represent standard deviation. Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Stk40: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline, ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scramble, ‡P < .001. Cpm: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline, ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scramble, *P = .02. Acta2: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline, *P = .02; Ces1d, ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline, †P = .004; Ly6e: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline, *P = .01; Sft2d2: ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline, *P = .03). All statistical tests were two-sided. RLU = relative light units; RT-qPCR = qualitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; ZD = Zn-deficient; ZR = Zn-replenished; ZS = Zn-sufficient.

In addition to the esophagus, anti-miR-31 treatment prevented the development of a ZD-induced hyperplastic tongue epithelium (32), as evidenced by a thinned epithelium (Figure 2B). Moreover, throughout the five-week study period, anti-miR-treated ZD rats showed a near normal hair coat, while ZD/saline or ZD/scrambled rats typically developed a poor coat with alopecia. Because ZD induces miR-31 expression in squamous skin associated with an inflammatory phenotype (12), it is likely that the improved skin phenotype in ZD rats was because of inhibition of miR-31 by anti-miR in skin, as in esophagus, tongue, and blood (Figure 1F).

miR-31 Antagonism and Esophageal Cellular Proliferation and Apoptosis

To assess esophageal cellular proliferation, we employed the proliferative marker PCNA. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis showed that the cell proliferation index (% of intensely stained PCNA-positive nuclei, expressed as mean ± standard deviation, n = 10 samples/group) in the ZD/anti-miR esophagus (27±5.1%) was markedly reduced (P < .001) relative to control ZD/saline (48±7.3%) or ZD/scrambled esophagus (47±4.2%) (Figure 3B). Similarly, immunoblot analysis showed reduced PCNA expression in ZD/anti-miR esophagi (Figure 3C) as well as in ZD/anti-miR tongue (Figure 2C) relative to ZD controls. Thus, miR-31 inhibition led to prominently decreased cellular proliferation.

To assess apoptosis induction, a luciferase-based chemical assay was used. ZD/anti-miR esophagus showed statistically significantly higher caspase 3/7 (P = .005, fold change = 10.7) and caspase 9 activities (P = .019, fold change = 3.8) than ZD/saline esophagus (Figure 3D), indicating that miR-31 inhibition induced apoptosis. Together, the data indicate that miR-31 inhibition suppresses the hyperplastic ZD esophageal phenotype via reduction of cell proliferation and activation of apoptosis.

Identification of Physiological miR-31 Targets in Esophageal Neoplasia

To identify genes with altered transcript levels in response to miR-31 silencing in vivo, we performed genome-wide expression profiling of esophageal mucosa from the four rat groups at 48 hours after the final LNA-antimiR dose (Supplementary Table 2, available online), using Affymetrix Rat Genome 230 2.0 GeneChip (n = 5 rats/treatment group). Hierarchical clustering of mRNA profiles revealed that the expression pattern in ZD/anti-miR esophagus was different from the control ZD/scrambled and ZD/saline esophagus, which were similar but distinct from ZS/saline esophagus (Figure 3E), implying that a large pool of the upregulated mRNAs in ZD/anti-miR RNAs correspond to derepressed miR-31 targets (29). Analysis of the array data revealed that the list of derepressed genes in ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/saline esophagus and in ZD/anti-miR vs ZD/scrambled esophagus were similar. In addition, the lists of differentially expressed genes were similar in ZD/scrambled vs ZS/saline and in ZD/saline vs ZS/saline, indicating that LNA/scrambled had little effect on gene expression. Guided by miR-31 target prediction bioinformatics, 13 derepressed genes (Figure 3F) were chosen from the intersection analysis between a joint set of genes from ZD vs ZS rats and that from ZD vs ZD/anti-miR group. To validate this prediction, qPCR analysis was performed (Figure 3G). Of the 10 genes that showed derepression with anti-miR treatment, six genes, including Stk40 (P < .001), Cpm (P = .02), Acta2 (P = .02), Ces1d (P = .004), Ly6e (P = .01), and Sft2d2 (P = .03) achieved a statistically significant difference between ZD/anti-miR and ZD controls (Figure 3G), thereby validating the bioinformatics prediction (Figure 3F) that such genes would be derepressed after miR-31 silencing.

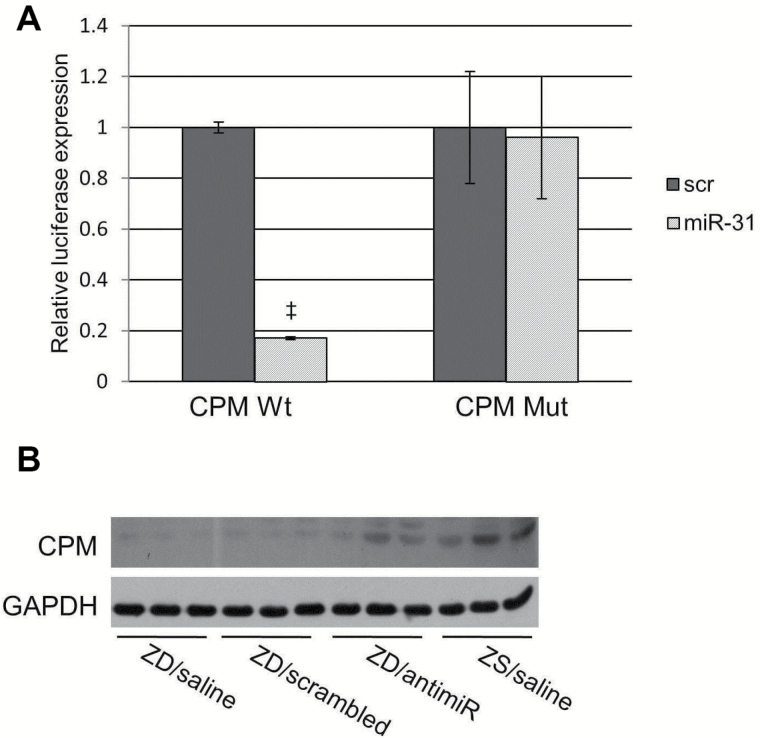

Stk40 (33,34) and Cpm (35) are of particular interest because of their roles in inflammation. We then determined if miR-31 directly interacts with Stk40 3’UTR by cotransfecting a pGL3 3′ UTR luciferase reporter vector with synthetic miR-31 (Figure 4, A-C). A two-fold decrease in luciferase activity was observed, indicating a direct interaction between the miRNA and Stk40 3′ UTR. Target gene repression was rescued by deletions in the complementary seed sites (fold change = 1.7) (Figure 4C). These data establish that Stk40, a known negative regulator of NF-κΒ–mediated transcription (33), is a miR-31 direct target. The regulation of Stk40 by miR-31 has been reported in ovarian cancer cells (21) and primary keratinocytes in psoriasis (34). Additionally, we demonstrated that the Cpm 3’ UTR is a miR-31 direct target by using the 3′ UTR luciferase reporter assay (Figure 5A). We showed by western blot that CPM protein was downregulated in hyperplastic ZD esophagus that overexpresses miR-31 and was restored upon miR-31 inhibition (Figure 5B). Although CPM has emerged as a potential cancer biomarker (35), the mechanism by which CPM contributes to carcinogenesis remains to be determined.

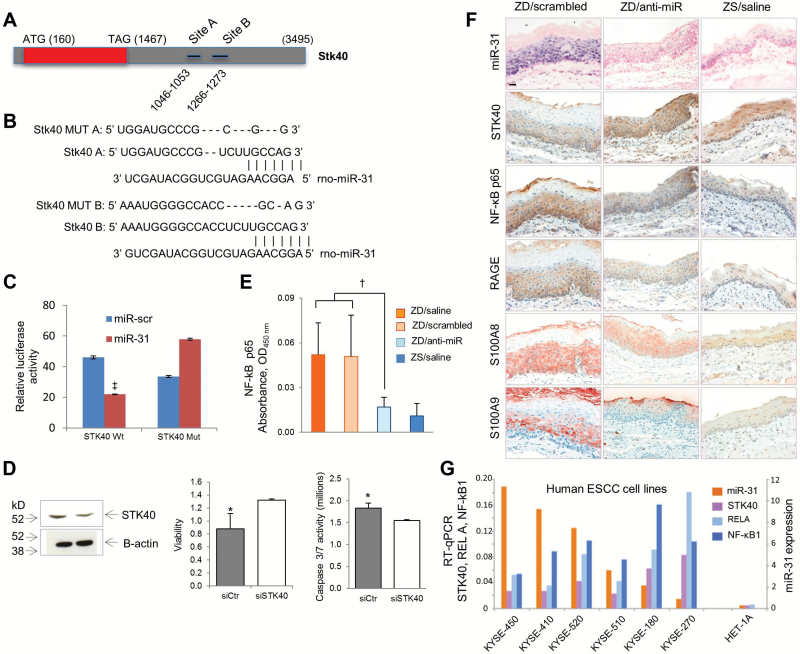

Figure 4.

Anti-miR-31 effects on Stk40-NF-κΒ–based inflammatory signaling. A-C) Stk40 3’ UTR is a miR-31 direct target. A) Stk40 3’UTR presents two miR-31 binding sites. B) Alignment of miR-31 seed region with Stk40 3’UTR. Sites of target mutagenesis are indicated (- = deleted nucleotides). C) Luciferase reporter assays indicates direct interactions between miR-31 and Stk40. Error bars represent standard deviation. ‡P < .001. D) STK40 silencing affects proliferation and apoptosis of esophageal squamous carcinoma (ESCC) cells. Western blot showing STK40 downregulation in KYSE-70 ESCC cells after transfection with STK40 siRNA; cell proliferation assay showing increased cell survival (*P = .03, error bars represent standard deviation), and luminescent assays showing decreased caspase 3/7 activity after STK40 silencing (*P = .015, error bars represent standard deviation). E) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay shows NF-κΒ p65 expression was statistically significantly reduced in Zn-deficient (ZD)/anti-miR vs control ZD cohorts (n = 6–8 rats/group, Tukey-HSD post hoc unpaired t test, †P = .002). Error bars represent standard deviation. F) In situ hybridization (ISH) analysis of miR-31 expression; immunohistochemical analysis of STK40, NF-κΒ p65, RAGE, S100A8, and S100A9 expression in esophageal formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. ZD/anti-miR (middle) and ZS (right) esophagi showing weak/diffuse miR-31 ISH signal (blue, 4-nitro-blue tetrazolium and 5-brom-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate); strong cytoplasmic STK40 (brown, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride [DAB]) but weak cytoplasmic NF-κΒ p65, RAGE (brown, DAB), and S100A8/A9 (red, 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate-chromogen) immunostaining. In contrast, hyperplastic ZD/scrambled esophagus (left) showing strong/abundant miR-31 ISH signal, weak/diffuse cytoplasmic STK40 immunostaining, but strong cytoplasmic immunostaining of NF-κΒ p65, RAGE, and S100A8/A9 protein. Scale bar = 25 μm. G) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis of miR-31, STK40, RELA, and NF-κΒ1 expression in six human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines and control esophageal squamous epithelial cells HET-1A, using RNU44 and OAZ1 and as normalizer for miR-31 and mRNA, respectively. qPCR analysis was performed in triplicate. All statistical tests were two-sided. ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; RT-qPCR = qualitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; ZD = Zn-deficient; ZS = Zn-sufficient.

Figure 5.

Cpm as a miR-31 direct target. A) Luciferase report assay showing direct interaction between miR-31 and Cpm. Inactivation of miR-31 binding site by site-direct mutagenesis rescues luciferase activity (experiments were performed three times, ‡P < .001, error bars = ± standard deviation). All statistical tests were two-sided. B) Western blot showing increase in CPM protein expression in Zn-deficient (ZD)/antimiR esophageal lysates relative to control ZD samples. ZD = Zn-deficient; ZS = Zn-sufficient.

Anti-miR-31 Effects on STK40-NF-κΒ–Based Inflammatory Pathway

We next focused our study on Stk40 because of its role in regulation of NF-κΒ (33), a key mediator of inflammation (36). The ZD-induced esophageal preneoplasia is accompanied by cytoplasmic NF-κΒ p65 overexpression and nuclear translocation of NF-κΒ phospho-p65 (37). We showed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that miR-31 inhibition led to statistically significantly lower NF-κΒ p65 levels in ZD/anti-miR esophageal lysates as compared with control ZD lysates (P = .002, fold change = -2.8) (Figure 4E), a result confirming that miR-31 inhibition suppresses NF-κΒ activity (34). To determine whether a connection occurs among miR-31, STK40, and downstream NF-κΒ signaling in esophageal neoplasia, we performed in situ detection of miR-31 expression combined with IHC analysis of the NF-κΒ p65-RAGE-S100A9 pathway (11), using FFPE esophageal tissues. In hyperplastic ZD/scrambled esophagus (Figure 4F), miR-31 overexpression was associated with downregulation of STK40 protein and accompanying upregulation of the NF-κΒ p65-RAGE-S100A9 inflammatory pathway. Remarkably, in vivo anti-miR-31 delivery reduced miR-31 expression, upregulated STK40 protein expression, and abolished this NF-κΒ p65-RAGE inflammation network, resulting in a noninflammatory esophageal phenotype that resembles the Zn-sufficient esophagus (Figure 4F). These in vivo findings show for the first time the important connections between oncomiR-31, STK40, and NF-κΒ p65–controlled signaling in esophageal neoplasia.

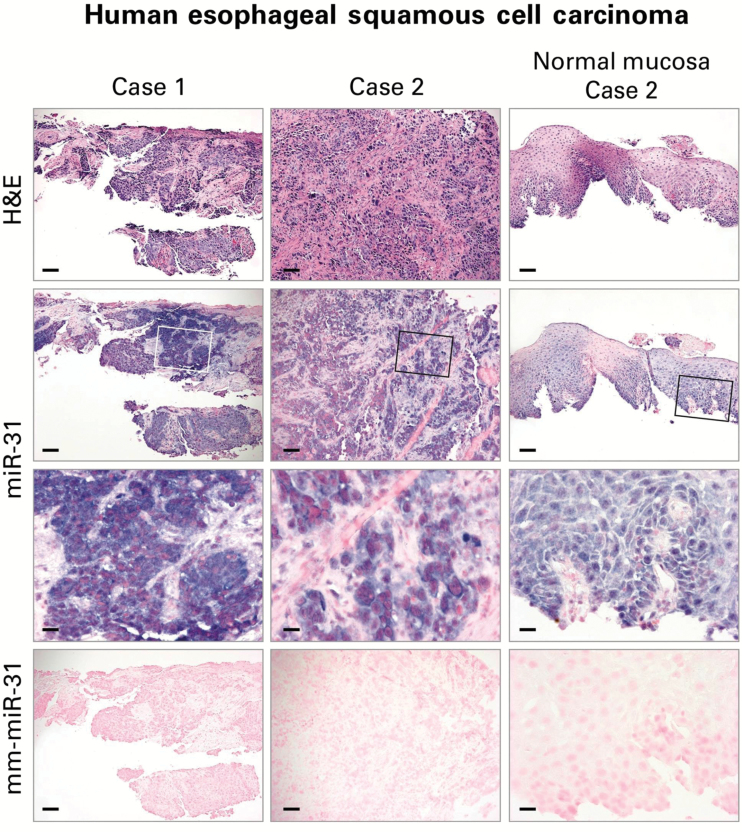

Cellular Localization of miR-31 Expression in Human ESCC Tissue

The cellular origins of miRNAs are of importance in the understanding of the mechanistic roles of miRNAs in tumor development. In order to determine the cellular localization of miR-31 in human ESCC, we evaluated miR-31 expression in archived FFPE human ESCC tissues by ISH (n = 12 case patients). Consistent with our previous study on miR-31 ISH in ESCC from carcinogen-treated ZD rats (12), all 12 cases of human ESCCs showed an intense and abundant miR-31 ISH signal in the tumor tissues and a moderate miR-31 signal in the adjacent esophageal mucosa (Figure 6). These results represent the first in situ detection of miR-31 in human ESCC, thereby providing support for miR-31 as a potential prognostic and/or therapeutic marker for ESCC.

Figure 6.

Localization of miR-31 in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissue by in situ hybridization (ISH). Representative sections of ESCC tissues are shown (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain). miR-31 ISH signal (blue, 4-nitro-blue tetrazolium and 5-brom-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate; counterstain, nuclear fast red) was intense and abundant in near serial formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of ESCC tumor tissue but moderate in adjacent nontumorus esophageal mucosa (Case 2). No ISH signal was obtained with mismatched mm-miR-31 (2 mismatches). Open rectangles are insets illustrated in panels directly below. Scale bars = 100 μm (H&E, miR-31, and mm-miR-31) and 25 μm (miR-31 inset). H&E = hematoxylin and eosin.

Overexpression of miR-31 and STK40 and NF-κΒ Expression in Human ESCC Cells

To define the role of STK40 in human ESCC cells, we analyzed cell proliferation and apoptosis after STK40 silencing. STK40 silencing, as shown by western blot, decreased caspase 3/7 activity (P = .015) and increased viability of esophageal cancer cells (P = .03) (Figure 4D). These results are consistent with the cell proliferation (Figure 3B) and apoptosis (Figure 3D) data in ZD rat esophagus that documented miR-31 overexpression with accompanying STK40 downregulation (Figure 4F). Next the expression of miR-31, STK40, RELA, and NF-κΒ1 were analyzed by qPCR in six human ESCC cell lines of the KYSE-series (KYSE-450, -410, -520, -510, -180, -270) (Figure 4G) (22). miR-31 was overexpressed in all six ESCC cell lines vs human normal esophagus cell line HET-1A. In four cell lines (KYSE-450, -410, -520, and -510), miR-31 overexpression was accompanied by low STK40 expression and an inverse relationship between STK40 and RELA/NF-κΒ1. These data document, for the first time, the important connections among oncomiR-31, STK40, and NF-κΒ in human ESCC cells.

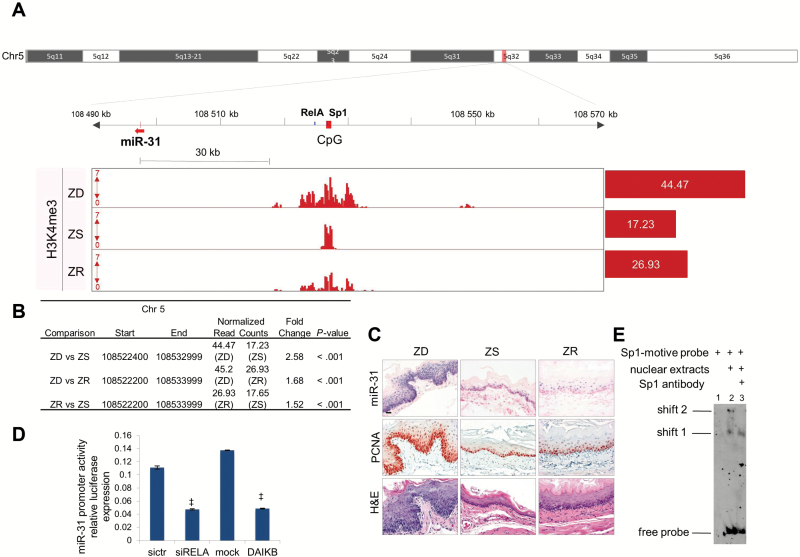

Activation of miR-31 Promoter Region in Zn-Deficient Esophagus

Finally, to elucidate the mechanisms by which miR-31 is upregulated by Zn deficiency, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) on esophagi from Zn-modulated rats (ZD, ZR, ZS). This analysis used antibodies for chromatin modification marks H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1), and H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3). Enrichment of H3K4me3-binding signals indicates the presence of a promoter region, whereas those of H3K4me1 and H3K27me3 represent marks for enhancers and repressed regions, respectively (38)

To identify enriched regions of histone modifications in ChIP-seq data, we performed peak-calling analysis using SICER algorithm (24) (Supplementary Methods, available online). By analyzing the genome occupancy of H3K4me3, we identified a promoter region approximately 30kb (kilobases) upstream of the mature sequence location of miR-31 (Figure 7A). We used Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (39) to visualize the promoter region of miR-31. H3K4me3 binding signals were statistically significantly enriched in ZD vs ZS esophagus (P < .001) (Figure 7B), indicating that the promoter is activated in ZD esophagus. With Zn replenishment, H3K4me3 levels were substantially reduced (ZD vs ZS = 2.58 as compared with ZR vs ZS = 1.52) (Figure 7B), accompanied by a near normal miR-31 level (northern blot, Figure 1B; ISH, Figure 7C) and esophageal phenotype (Figure 7C). On the other hand, the histone mark for enhancer H3K4me1-binding signals was minimally enriched in ZD esophagus, and no enriched locations were found for repressor H3K27m3-binding signals (Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3, available online).

Figure 7.

ChIP-seq identification of the promoter region of miR-31 and TFBs. A) Integrative Genomics Viewer view shows the putative miR-31 promoter region in Zn-deficient (ZD) rat esophagus: miR-31 (red arrow), CpG island (red box), and TFBs NF-κΒ/Sp1 (blue box). The values on the y-axis for ChIP-seq data are input-normalized intensities; the values on red barplots are normalized read counts/library size x 1 000 000. B) Table shows differentially enriched regions (H3K4me3) among Zn-modulated groups. C) Hematoxylin and eosin stain analysis of histology, in situ hybridization analysis of miR-31 expression, and immunohistochemical analysis of the proliferation marker PCNA of Zn-modulated esophagus (scale bars = 25 μm). D) NF-κΒ transcriptionally activates miR-31. Luciferase experiment shows downregulation of miR-31 promoter activity after NF-κΒ silencing or the overexpression of a NF-κΒ–dominant active inhibitor (experiments were performed three times, ‡P < .001, error bars = ± standard deviation). All statistical tests were two-sided. E) DNA mobility shift assay shows the binding of Sp1 to Sp1-probe motive. Lane 1: labeled Sp1-motive probe. Lane 2: two complexes at different molecular weights (shift 1, shift 2) are formed by the addition of nuclear extracts from HELA cells to Sp1-motive probe. Lane 3: anti-Sp1 antibody disrupts the higher molecular weight complex (shift 2). DAIKB = NF-κΒ–dominant active inhibitor; siRELA = NF-κΒ silencing; ZD = Zn-deficient; ZR = Zn-replenished; ZS = Zn-sufficient.

This miR-31 promoter region is conserved in humans and rats (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). To test the presence of putative cis-regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers) in humans, we used public ChIP-seq data of several human cell lines and identified binding sites of PolII in the CpG island corresponding to rat island 77. Using chromatin state dynamics from ENCODE chromatic portal (40), we determined that this region is characterized by the presence of poised or active promoters (Supplementary Figure 1A, available online). Because a genome map of cis-regulatory elements is not available in rat genome, we used Blat, the University of California, Santa Cruz Genome Browser (41), to find a conserved region in rats similar to CpG island 77. Using Blat (Supplementary Methods, available online), we found a region with 85.2% similarity with humans. This region is indeed the promoter region that we have identified in rats (ChIP-seq data, Supplementary Figure 1B, available online).

Identification of RelA and Sp1 in miR-31 Promoter Region

We downloaded the DNA sequence from the rat genome (rn4) located at chr5: 108.520.153-108.537.803 that showed the highest continuous peak enriched in ZD esophagus for chromatin mark H3K4me3. To find the transcription factor binding site (TFBs), we used Jaspar Core (25) and TRANSFAC database (26) and identified one predicted RelA (p65 subunit of NF-κΒ) binding site: GGGAATTCCCC (5:108,526,856-108,526,866 [+]) and one TFBs for Sp1: GGACGCCCCGCCCCGGCCCCGCCCCGACGG (5:108,527,171-108,527,194 [+]). These sequences are both located within the miR-31 promoter region (Figure 7A). The TFBs for rat NF-κΒ p65 (subunit of NF-κΒ transcription factor complex) is located 2kb downstream of the CpG island 94 (Figure 7A). We cloned this sequence of approximately 400bp in a promoterless vector (PGL3basic) and cotransfected this construct along with a NF-κΒ p65 siRNA or a dominant active (DA) I-κΒa in 293T cells. NF-κΒ p65 knockdown or inhibition resulted in a greater-than-two-fold decrease in miR-31 promoter activity, suggesting that this microRNA is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κΒ p65 (Figure 7D). Sp1 is located within the CpG island of the miR-31 promoter (Figure 7A) and was validated through electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Figure 7E). These findings indicate that the putative promoter region may be bound by NF-κΒ transcription factor complex together with the Sp1 transcription factor.

Discussion

ESCC is a lethal cancer because of diagnosis at advanced stage and lack of effective therapies. In comparison with other human cancers, ESCCs exhibit few expression changes in microRNAs and no bona fide physiological targets. miR-31 acts as an oncomiR in ESCC (Figure 6) (13,14) and tongue SCC (12,18). Its biological functions in these cancers, however, have not been defined and its potential as a therapeutic target not assessed. Our rat model that recapitulates features of human ESCC, including Zn deficiency, miR-31 overexpression, and inflammation (7,8,13,14), provides an opportunity to decipher the mechanism of oncomiR-31 function in ESCC and its relationship to ESCC promotion by dietary Zn deficiency. Using this model, the current study shows that in vivo miR-31 antagonism by systemically administered LNA-anti-miR decreased miR-31 overexpression in esophagus/tongue and circulating blood and prevented the development of a preneoplastic phenotype in esophagus and tongue in ZD rats. Importantly, we show that systemic delivery of anti-miR-31 reduces cellular proliferation, activates apoptosis, and represses the miR-31 associated STK40-NF-κΒ–based inflammation signaling in the esophagus. Thereby, the tumorigenic effects of Zn deficiency are overcome and esophageal neoplasia inhibited. These data are the first evidence that in vivo anti-miR-31 delivery exerts multiple anticancer activities and inhibits ESCC neoplasia.

To pinpoint biologically significant miR-31 targets from the hundreds of putative targets generated by target prediction algorithms (42), our approach has led to identification of Stk40 as a biological miR-31 target by using in vivo miR-31 antagonism and microarray analysis of derepressed genes. Although Stk40 was identified as a miR-31 direct target in ovarian cancer cell lines (21) and psoriasis (34) and Stk40 is a known negative regulator of NF-κΒ signaling, the important connections between miR-31, Stk40, and NF-κΒ signaling have not been demonstrated in human cancers. Our study shows for the first time that systemic delivery of anti-miR-31 suppresses the esophageal neoplasia by derepressing its target, Stk40, and inhibiting the associated STK40-NF-κΒ–controlled inflammatory pathway. Because the same connections among miR-31, Stk40, and NF-κΒ signaling are also shown in human ESCC cell lines, our in vivo results provide a mechanistic rationale for clinical development of miR-31 as a biomarker and treatment target for ESCC patients.

Transcription factors are known to regulate miRNA expression in a tissue- and disease-specific manner (43). By performing ChIP-seq on esophagi from Zn-modulated rats using an antibody for chromatin modification mark, H3K4me3 that detects promoters (44), our analysis identified a miR-31 promoter region activated in ZD esophagus. Dietary Zn replenishment restored the regulation of this genomic region to the inactive state, miR-31 levels, and the hyperplastic esophageal phenotype to near normal. These data provide the first evidence that miR-31 promoter activity is regulated by dietary Zn. In addition, our motif-finding analysis demonstrates the presence of an NF-κΒ binding site in the miR-31 promoter region. NF-κΒ p65 knockdown resulted in a decrease in miR-31 promoter activity, indicative of transcriptional regulation of miR-31 by NF-κΒ p65. Together, these data define a mechanism whereby Zn deficiency upregulates miR-31 by activating its promoter/TFBs and unleashing miR-31–associated, STK40-NF-κΒ–controlled inflammatory signaling to produce a preneoplastic phenotype.

A limitation of this study is the fact that the endpoint was the early hyperplastic and inflammatory esophageal phenotype rather than esophageal cancer itself. Studies are in progress to specifically address this issue.

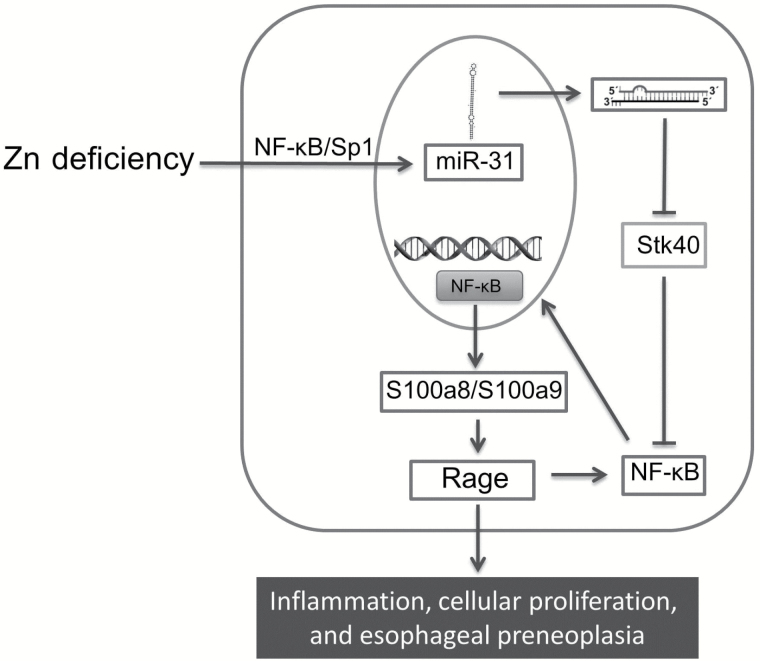

In summary, our in vivo work defines the signal pathway underlying the interaction of Zn deficiency and miR-31 overexpression in promoting esophageal neoplasia (Figure 8). OncomiR-31 is a critical target involved in ESCC pathogenesis. Antagonism of miR-31 leads to suppression of esophageal neoplasia, thereby providing support for clinical development of miR-31 as a biomarker and therapeutic target for this deadly disease.

Figure 8.

Molecular pathway underlying interaction of Zn deficiency and miR-31 overexpression in promoting esophageal preneoplasia. Zn deficiency induces miR-31 overexpression, leading to downregulation of its direct target Stk40. Stk40 downregulation activates NF-κB and Rage through S100a8/a9 dimer protein complex, thereby promoting inflammation and cellular proliferation to produce the preneoplastic esophageal phenotype.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA118560, R21CA127085, and R21CA152505 to LYF; U01CA152758 and U01CA166905 to CMC).

Supplementary Material

The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We thank K. Huebner for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. We also thank S. Costinean and S. Bicciato for technical advice, J. Altemus for technical assistance, and D. Guttridge for the DA IKB-α plasmid. MG was supported by the Kimmel Award.

Data from the in vivo silencing of miR-31 were presented in part at the 2013 meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (Washington, DC). Abstract # LB-241. Taccioli et al.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ambros V. MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell. 2003;113:673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435 (7043):828–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10 (10):704–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abnet CC, Lai B, Qiao YL, et al. Zinc concentration in esophageal biopsy specimens measured by x-ray fluorescence and esophageal cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97 (4):301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mandard AM, Hainaut P, Hollstein M. Genetic steps in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Mutat Res. 2000;462(2–3):335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fong LY, Nguyen VT, Farber JL. Esophageal cancer prevention in zinc-deficient rats: rapid induction of apoptosis by replenishing zinc. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1525–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taccioli C, Chen H, Jiang Y, et al. Dietary zinc deficiency fuels esophageal cancer development by inducing a distinct inflammatory signature. Oncogene. 2012;31:4550–4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taccioli C, Wan SG, Liu CG, et al. Zinc replenishment reverses overexpression of the proinflammatory mediator S100A8 and esophageal preneoplasia in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:953–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alder H, Taccioli C, Chen H, et al. Dysregulation of miR-31 and miR-21 induced by zinc deficiency promotes esophageal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33 (9):1736–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin RJ, Xiao DW, Liao LD, et al. MiR-142-3p as a potential prognostic biomarker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105 (2):175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang T, Wang Q, Zhao D, et al. The oncogenetic role of microRNA-31 as a potential biomarker in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Sci (Lond). 2011;121:437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laurila EM, Kallioniemi A. The diverse role of miR-31 in regulating cancer associated phenotypes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52 (12):1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bandres E, Cubedo E, Agirre X, et al. Identification by Real-time PCR of 13 mature microRNAs differentially expressed in colorectal cancer and non-tumoral tissues. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu X, Sempere LF, Ouyang H, et al. MicroRNA-31 functions as an oncogenic microRNA in mouse and human lung cancer cells by repressing specific tumor suppressors. J Clin Invest. 2010;120 (4):1298–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wong TS, Liu XB, Wong BY, et al. Mature miR-184 as Potential Oncogenic microRNA of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Tongue. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2588–2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lajer CB, Nielsen FC, Friis-Hansen L, et al. Different miRNA signatures of oral and pharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas: a prospective translational study. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:830–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bruegger C, Kempf W, Spoerri I, et al. MicroRNA expression differs in cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas and healthy skin of immunocompetent individuals. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22 (6):426–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Creighton CJ, Fountain MD, Yu Z, et al. Molecular profiling uncovers a p53-associated role for microRNA-31 in inhibiting the proliferation of serous ovarian carcinomas and other cancers. Cancer Res. 2010;70 (5):1906–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shimada Y, Imamura M, Wagata T, et al. Characterization of 21 newly established esophageal cancer cell lines. Cancer. 1992;69 (2):277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10 (3):R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zang C, Schones DE, Zeng C, et al. A clustering approach for identification of enriched domains from histone modification ChIP-Seq data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25 (15):1952–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sandelin A, Alkema W, Engstrom P, et al. JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D91–D94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knuppel R, Dietze P, Lehnberg W, et al. TRANSFAC retrieval program: a network model database of eukaryotic transcription regulating sequences and proteins. J Comput Biol. 1994;1 (3):191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu CG, Calin GA, Meloon B, et al. An oligonucleotide microchip for genome-wide microRNA profiling in human and mouse tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101 (26):9740–9744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fluiter K, ten Asbroek AL, de Wissel MB, et al. In vivo tumor growth inhibition and biodistribution studies of locked nucleic acid (LNA) antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31 (3):953–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elmen J, Lindow M, Silahtaroglu A, et al. Antagonism of microRNA-122 in mice by systemically administered LNA-antimiR leads to up-regulation of a large set of predicted target mRNAs in the liver. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36 (4):1153–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elmen J, Lindow M, Schutz S, et al. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008;452 (7189):896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janssen HL, Reesink HW, Lawitz EJ, et al. Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. N Engl J Med. 2013;368 (18):1685–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fong LY, Zhang L, Jiang Y, et al. Dietary zinc modulation of COX-2 expression and lingual and esophageal carcinogenesis in rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang J, Teng L, Liu T, et al. Identification of a novel serine/threonine kinase that inhibits TNF-induced NF-kappaB activation and p53-induced transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309 (4):774–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu N, Meisgen F, Butler LM, et al. MicroRNA-31 is overexpressed in psoriasis and modulates inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production in keratinocytes via targeting serine/threonine kinase 40. J Immunol. 2013;190 (2):678–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Denis CJ, Lambeir AM. The potential of carboxypeptidase M as a therapeutic target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17 (3):265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336 (15):1066–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fong LY, Jiang Y, Riley M, et al. Prevention of upper aerodigestive tract cancer in zinc-deficient rodents: inefficacy of genetic or pharmacological disruption of COX-2. Int J Cancer. 2008;122 (5):978–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473 (7345):43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14 (2):178–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rosenbloom KR, Dreszer TR, Long JC, et al. ENCODE whole-genome data in the UCSC Genome Browser: update 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D912–D917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karolchik D, Hinrichs AS, Kent WJ. The UCSC Genome Browser. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2012;Chapter 1:Unit 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thomas M, Lieberman J, Lal A. Desperately seeking microRNA targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17 (10):1169–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11 (9):597–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, et al. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130 (1):77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.